Styles and the dating of sculptures

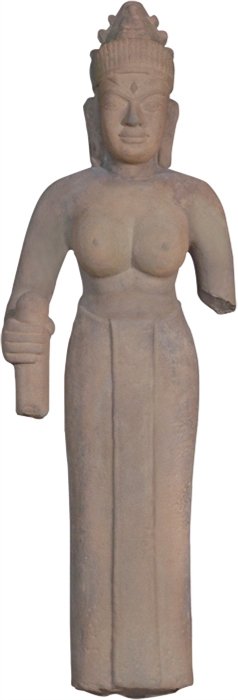

30. Tara, Free-standing,

Sandstone, height 94 cm,

Dong Duong style,

9th – 10th Century.

The divinity is standing, sculpted in the round rather than leaning against a stele. She wears a representation of Amitabha in her hair. Both arms (one is broken today) gripped two vertical staffs that served as supports. She is dressed in a sarong with vertical folds, her breasts are heavy and rounded. Her face is the archetype of the Dong Duong style.

In art, dating is much more difficult than iconographical identification. It even happens that, through laxity or insufficient experience with the object, the latter, though certainly in a scholarly way, is invoked as a servile tool for the former. This is a dangerous practice: “You have a solution. Always the same one: iconography. One step further, it calms your anxieties and answers all your questions.” (Daniel Arasse, On n’y voit rien [We see nothing], Descriptions, p. 32). Unluckily, the iconographical tool seems to have been overused. It is striking to notice that the term “patina” is wholly unknown to most authors. And yet this is the key to dating. A stone, a bronze, have a patina imposed by the passage of time, that situates the object in it. This patina has technical components that predispose, intellectually, the object’s dating.

To precisely date Cham sculptures, to propose the characteristics of particular styles, was the task that, as of the beginning of the twentieth century, French specialists took upon themselves.

It was due to Henri Parmentier and his Descriptive Inventory of Cham Monuments in Annam (whose publication, begun in 1912, was completed in 1918), but above all, Philippe Stern and his remarkable The Art of Champa (former Annam) and its Evolution published in 1942 and Jean Boisselier (Statuary of Champa, 1963) that a general but often-contested dating system was established. It goes without saying that more recent discoveries, in particular in 1982 (on the An My site) not only allowed some of these datings to be made more precise, improved or even contradicted, but also made it possible to determine that they needed to be moved back in time, and to place them regionally (Tran Ky Phuong, Ngo Van Doanh). The An My site, in the Tam Ky district, Quang Nam province, notably delivered several remarkable sculptures (linga- yoni, dikpala, etc.) that Vietnamese archaeologists date from the first half of the tenth century. In addition, in 1987-88, numerous new Cham sites were identified, either on the plain (Tuy Phuoc and An Nhon districts) or on the high plateaux (Gia Lai, Kontum). Parmentier’s classification no longer has any didactic value. On the other hand, in terms of iconography and dating, the work of Stern and that of Boisselier remain the reference.

Let us briefly recall how these men formulated their reasoning and their conclusions. Parmentier began with a principle: “Between two undated forms of art, the most perfect one is the oldest.” His observation, in the field, of temples and Cham sculptures brought him, guided by this principle, to divide Cham art into two periods. The first, called “primary”, stretches from the seventh to the tenth centuries, and is itself divided into three “arts” that can overlap chronologically: “primitive” art of the seventh to tenth centuries, illustrated notably by My Son A1; “cubic” art from the seventh to ninth centuries, as at Hoa Lai, and “mixed” art, in the tenth century, as at Dong Duong. The second period, called “secondary”, can here again be separated into “classic” art of the eleventh century, such as at the Silver Towers, “derived” art, in the twelfth to seventeenth centuries, as at Po Klaung Garai, and “pyramidal” art, from the tenth to fourteenth centuries, as at Po Nagar in Nha Trang.