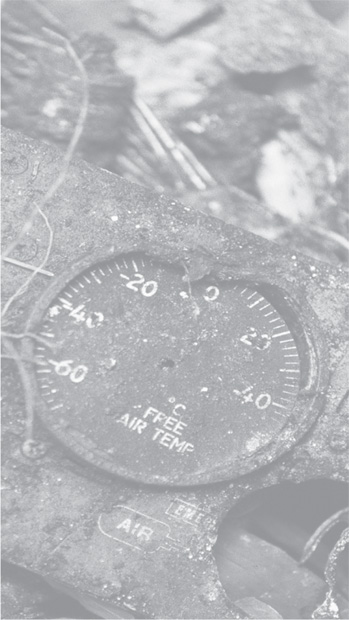

A witness to the devastation: a temperature gauge from the cockpit of the LANSA plane, 1998. (Photo courtesy of Juliane (Koepcke) Diller)

It’s January 3, 1972. Some of the LANSA passengers’ family members have lost hope. Ten days after the disaster, the prospect of finding survivors fades. The search for the missing airplane is officially abandoned. Only the patrol made up of civilians and family members does not yet give up. The numerous journalists who came to Pucallpa on Christmas, and have continuously besieged the city since then, depart—the story seems to be over. My father is staying on the farm belonging to his acquaintance Peter Wyrwich. Has he, too, accepted the fact that he has lost his wife and daughter?

Meanwhile, Beltrán Paredes, Carlos Vásquez and Nestor Amasifuén, for those are the names of the three forest workers who find me in their camp, kindly take care of me. They give me fariña to eat, a mixture of roasted and grated manioc, water and sugar, the typical fare of the forest workers, hunters and gold panners. But I can get almost nothing down. As well as they can, they attend to my wounds and take still more maggots out of my arm.

“By all that’s sacred,” Don Beltrán confesses to me as he picks one after another out of my wound, “at the first moment I thought you were the water goddess, Yacumama.”

“Why?” I ask with surprise. I know whom he means. Yacumama is the name the Indians give to a nature goddess who lives in the water. Pregnant women have to avoid looking at her at all costs, or else she will come later and take the child. But why did they think I was she?

“Well, because you’re so blond. And because of your eyes. And because there’s no one living here far and wide. Especially not any whites. Good thing you spoke to us right away.”

That’s how I learn that this river really is completely uninhabited.

“What about the other passengers?” I ask the men. “Were they rescued?”

Speechless, the men look at me with wide eyes. Finally one of them pulls himself together. It’s Don Nestor, and his voice sounds hoarse.

“No, señorita,” he says, “not even the airplane has been found. It has simply disappeared in the jungle, as if it closed its fist around it. As far as I know, you are the only survivor.”

The only survivor? Me? That seems inconceivable to me. If I’m the only one … that means … I try not to finish this thought, but can’t help it: My mother wasn’t found either?

“No one,” confirms Don Carlos, who has been silent until now. Only now do I realize that I spoke my thought aloud. “It’s a miracle that you’ve turned up here, that you’re alive, able to talk to us. And that we came here. For we actually weren’t going to. When the rain came today, we considered whether to go to the shelter or not. To be honest, we check on the boat pretty rarely. We might well not have come at all. But Nestor said, ‘Oh, come on, the weather is deceptive. Let’s go to the tambo. There we’ll at least have a roof over our heads.’ I can still hardly believe it. How long were you on the move?”

The men give me pants and a shirt to put on. I eat one or two spoonfuls of the sour-smelling fariña. Then I’m already full. Apparently, my stomach has shrunk.

Suddenly another two men come out of the darkness. The bad weather—or fate?—leads them all to this shelter, today of all days. It’s Amado Pereira and Marcio Rivera, and they, too, are thunderstruck when they see me.

“Whom do we have here?” Don Marcio asks with surprise.

And again I have to tell what happened. Again the response is pure astonishment. We exchange information, and I learn details about the large-scale but unsuccessful search operation. That evening we speak for a long time.

“We’ll get you out of here,” says Don Marcio, and he confers with the other men. Actually, they want to get me as quickly as possible to a doctor, as if they were afraid I might have more serious injuries, after all, and could die on them. But then they agree that it’s safer to spend the night here. The three men who first found me will remain in the forest, as they originally intended. Don Marcio and Don Amado volunteer to take me to Tournavista early the next morning in the boat.

That night I don’t dare to say how uncomfortable I find the palm-bark floor in the shelter and that I’d rather sleep in the sand. So all six of us spend the night in the tambo. The men give me their only mosquito net, but I sleep poorly, anyway. My wounds, out of which we have meanwhile taken about fifty maggots, hurt unbearably. Early in the morning, when it’s still dark, we set off. I try to walk, but they carry me over the last stretch, lay me in the boat and cover me with a tarp.

And then I simply let go. I’m so boundlessly tired. I doze off, again and again. During my waking hours I look at the riverbank gliding past me and talk to the men. I learn the name of the river. It’s the Río Shebonya, and it really is still completely uninhabited.

It’s not long before the story of my rescue fills newspapers all over the world in the most unbelievable variations. The wildest version is the myth that I built a raft for myself, out of branches and leaves, and floated down the Río Shebonya on it. Indians saw me drifting by, unconscious, and pulled the raft ashore. When I came to, I said only: “There are dead people,” and then I passed out again. Once it’s out there, hundreds of journalists copy this account. Even today you can still read it in newspapers or on the Internet. I’ve received letters mainly from rational-minded children like those first graders from Warner Robins in the United States who were justifiably eager to know how I managed to build a raft without any tools. And why didn’t my raft made of branches and leaves sink? Other reports describe my journey on the boat with Don Marcio and Don Amado like this: Then she fell into a deep oblivion. That was not the case. On the contrary—though I repeatedly nodded off, I took in much of the monotonous journey.

The trip goes on forever, and it’s a long time before we finally reach the mouth of the Río Shebonya where it flows into the Río Pachitea. On the bank of the Pachitea lies the village of Tournavista. It becomes clear to me: I could never have managed this alone.

Around noon the men stop to eat something. We go ashore to a house in the middle of a pasture. As I approach, some children run away, screaming; and a woman turns away with horror, her hand pressed to her mouth: “Those eyes! I can’t look at them! Oh God, those terrible eyes!”

I ask my companions: “What’s wrong with her? What’s going on with my eyes?”

And then they explain to me that my eyes are completely red. Apparently, all the blood vessels have burst, and there’s no white left, everything is bloodred. Even the iris has turned red. I’m surprised, for I can see quite well.

Later I will look in a mirror and understand well the woman’s terror. It really does look as if I no longer have eyes, but only bloody sockets. No wonder these people here think I’m a jungle spirit. Nonetheless, they give me a bowl of soup, but again I get almost nothing down.

Around four o’clock in the afternoon, we dock in Tournavista. Our arrival provokes great excitement. Immediately a stretcher is brought over, and I find that embarrassing, for I can walk on my own!

The nurse who comes to meet me I know from the past. Her name is Amanda del Pino, and she once gave me a tetanus shot, back before I came to Panguana. Now she wants to give me penicillin, but I refuse. My father is highly allergic to this antibiotic, and I don’t know whether I might have inherited this intolerance from him. Sister Amanda lets herself be persuaded, and she injects me with a different medication.

Everyone is very careful with me. They handle me with kid gloves. Someone takes a photo that will soon appear in Life magazine. In it, I’m standing on a porch. Someone has put a bathrobe over my shoulders. The nurse is holding me by the arm and looks very concerned. She barely asks me any questions. Still, the next day there’s an interview in the newspaper that I definitely didn’t give.

After my wounds have been cleaned and disinfected, and I’ve received an injection, an American female pilot named Jerrie Cobb appears and offers to take me on her plane to the Instituto Linguístico de Verano in Yarinacocha, where the missionaries are studying the languages of the Indians and translating the Bible. There are some doctors there, she says, and I could get better treatment and recover comfortably. Though the prospect of getting on a plane again frightens me, I’m too weak to protest energetically. And she’s probably right, I think.

So a short time later, I’m aboard a twin-engine Islander, and as Jerrie Cobb tries to reassure me with the information that she’s the first woman in the world to be trained as an astronaut, and with her I will fly as safely as in the arms of an angel, I don’t find the strength to insist on being allowed to fly sitting up. Jerrie finds it safer for me to lie down, and so the twenty-minute flight becomes a torment for me. Above all, it happens when Jerrie, who apparently doesn’t notice my fear, really leans the airplane into the turns.

The “linguists,” as the missionaries of the Wycliffe Bible Translators in Yarinacocha are generally called, give me a warm welcome. The family of Dr. Frank Lindholm takes me in, and immediately I receive medical attention again. The doctor removes more maggots from my arm, as well as from the cut in my leg, in which the beasts had also nested. The hole in my arm is deep. How deep no one knows exactly, and therefore I now receive the first of countless treatments during which I have to clench my teeth to keep from screaming loudly: Dr. Lindholm soaks a twenty-inch strip of gauze in iodoform and stuffs it deep into the wound. It has to remain there until the next day, when it will be pulled out and replaced with a new one. That’s the only way, he explains to me, to make sure that the tubular wound heals cleanly from the inside to the outside. Then he pulls a pretty long wooden splinter out of the sole of my foot, which I hadn’t even perceived. All over my body I have insect bites, which are inflamed and swollen. These are now treated too.

When this is over, I’m asked what I’d like to eat. On impulse I say: “A chicken sandwich.” To my great joy they immediately make me one, and I eat it very enthusiastically.

I’m safe. And with this certainty I fall into a deep sleep.

In the restaurant our food is served. It’s a gorgeous late afternoon. The light glistens gold on the water, gently rippled by the wind. Over there, a bit farther up the lagoon, is where I rested back then in Dr. Lindholm’s house. Today there are only a few linguists left there. When I came with Werner Herzog, they already had to reduce the size of their camp. Just a few months ago, after an interview with me was broadcast on CNN, the widow of another doctor, whom I had moved in with after several days, Mrs. Fran Holston, sent me a photo showing me with her two daughters in the garden. You can scarcely tell by looking at me in this picture that I had just gone through that eleven-day odyssey. In a skirt and blouse, borrowed clothes, I’m smiling at the camera. I was surprised how little I felt at the sight of this photograph, as if the girl in it were someone else entirely. I had a similar experience during the shooting of the documentary Wings of Hope with Werner Herzog.

To this day it seems to me a stroke of good fortune that in 1998 our telephone rang at home in Munich and a man introduced himself with the words: “My name is Werner Herzog. I’m a film director. I would like to make a documentary about your fate.”

By that time the crash was twenty-seven years in the past. I hadn’t had many good experiences with journalists and filmmakers, and so had shied away from all that, years ago. Those days I rejected interview requests categorically, and was all the more averse, of course, to appearances on talk shows. I was tired of being asked the same questions over and over again, all my life, and being perceived exclusively as the rare survivor of an unbelievable story. Since then, I had a life of my own, had been married for nine years, and there was in my opinion a host of topics more exciting than rehashing, again and again, the details of the crash. Especially since it had been my experience that, whatever I said, the journalists seemed not to listen and in the end would write what they had already imagined, anyhow, or what they thought the readers wanted to hear. But suddenly I had Werner Herzog on the telephone, and he wanted to shoot a film with me!

He apparently sensed my hesitation, for he said: “If you want more information about me, then you can read about me on the Internet. I would also be happy to send you a few of my films.”

“That’s not necessary,” I said after I had overcome my initial surprise. “Of course, I know who you are, Mr. Herzog.” I had always admired this extraordinary director. I had seen many of his films. I could hardly believe I was talking to him on the telephone. And his proposal also seemed unbelievable to me at first.

For Werner Herzog did not just want to conduct interviews with me, as so many others had done. He was planning something unheard of: twenty-seven years after the crash, he wanted to return with me to the place where everything had happened. He also wanted to retrace my path back to other people. Should I actually do it? On the other hand: How can anyone really turn down an offer like that?

Herzog suggested that I think about everything. He sent me books and some of his films I hadn’t yet seen, and gave me time. I consulted with my husband, for his opinion was always really important to me. He has incredible insight into people, and I know that I can rely on his advice. He said: “Maybe it will be good for you. You will probably never have an opportunity like this again.”

And so I contacted Werner Herzog and informed him that I was interested in his project. We met at an excellent Munich restaurant. On this occasion I became acquainted with the cameraman Erik Söllner. Later, too, during the filming, Werner Herzog set great store by his opinion.

That evening Herzog explained his plan to us: He wanted to send an expedition to find and make accessible the spot where the wreckage of the Lockheed L-188A Electra still lay scattered in the jungle, for the crash site was still roughly known among the locals. I put Werner Herzog in contact with Moro, who had looked after Panguana over all the years during which I couldn’t come to the research station. Despite his help and that of several natives, three expeditions Herzog sent to locate the wreckage of the Lockheed Electra returned empty-handed. Only the fourth was successful. Together with his then-eight-year-old son, the director proceeded to the location to view the pieces of wreckage, which were strewn over a stretch of about ten miles in the jungle.

On his return to Munich, he told me that I’d be amazed how well some of the wreckage was still preserved. But he also had to face the fact that the terrain was so rough that on some days it took experienced native macheteros hours to advance even only a hundred yards. The film crew, along with all the equipment, couldn’t possibly make it to the crash site on foot. Several times it looked as if the project might fail, but not with Werner Herzog. He balked at no means or exertion to put his plan into action. If you couldn’t get there on foot, then it would have to be by air. And so he decided to have a small swath cut in the jungle near the largest pieces of wreckage, just large enough so a helicopter could land.

Everyone thought that all this would upset me terribly, but to my astonishment I realized that I was confronting everything oddly emotionlessly. More than the prospect of seeing the place again, what made me nervous was the fact that I’d have to speak on camera, and I wondered whether I would manage that well enough. My husband always says that I’m a perfectionist, and he is undoubtedly right. But when you’re standing in front of the camera for someone like Werner Herzog, then you ultimately want to do a good job. And then, in early August 1998, things got under way.

With American Airlines, we flew via Dallas to Peru, which was not the shortest route and made the trip still longer and more arduous than a direct flight from Europe already is, anyhow. But that airline permitted substantially more baggage than any other, and, of course, a film crew has a great deal of luggage and equipment. Some of it had been sent ahead already, and once again it was Alwin Rahmel who saw to it that everything got through customs smoothly.

With the crew we got along excellently from the beginning. Everything was perfectly organized, and I enjoyed not having to worry about anything, for once. In Lima, we visited the archives of the two large newspapers, La Prensa and El Comercio. Here I saw photos of another LANSA crash, the one near Cuzco, pictures of corpses on a field that were so horrible that they could not be published at the time. The bodies were battered, twisted and contorted from the impact, and the sight shocked me profoundly, for I, of course, could not help thinking constantly of my own accident and in what condition the people must have been who had not been as lucky as I was.

It really was a strange journey the director took me on. To persuade me to get on an airplane again, twenty-seven years after my accident, that flew the exact same route as the one on which I crashed was still relatively simple. After all, I had already had to take that flight several times since then to save time getting to the jungle. But he even put me in the same seat as on the LANSA plane out of which I fell from the sky back then: row 19, seat F. Actually, I would have preferred to have traveled by bus, for here, too, a great deal had changed since the days of my youth, and now it took “only” twenty hours from Lima to Pucallpa. But Werner Herzog is a man with great powers of persuasion, and so I changed my mind and agreed to fly with him. Today I’m glad I did so. For if the filmmaker had not brought me face-to-face with that part of my past and drawn me closer to the public again, who knows whether I would now be capable of advocating this way for Panguana to a larger audience?

So I overcame my fear. And on camera we flew over the spot where it had happened. Werner Herzog used that moment, of course, and interviewed me: At that exact point I recounted how I had experienced the crash. And fortunately it went so well on the first try, we didn’t have to repeat it. My husband was at my side the whole time, and that was enormously important for me. I believe that you can tell in this film how much we support each other, how much we’re there for each other when the other needs it.

On the way from Pucallpa to the jungle, I experienced many a surprise. Along the new Carretera Marginal de la Selva, the forest was being cleared everywhere. With saw and fire civilization was boring its way into the wilderness. My heart bled, for I knew quite well how much life perished in the flames. Meanwhile, an iron bridge had been built across the Río Shebonya, the river I followed; and a couple miles from it, a woman from the Andes had opened a kiosk, where we stopped to get something to drink. I did not believe my eyes when I saw what she had leaned against the outside of the house: It was actually a fully intact door from the LANSA plane, which someone must have brought here. On it the Indian woman had written in flawed Spanish: Juliana’s door. This enterprising woman had apparently realized immediately what a magical appeal this relic of my past would have. Indeed, everyone I talk to about it calls this kiosk, which has meanwhile grown into a small grocery store that sells drinks, “The Door.” Of course, Werner Herzog filmed me there. Whenever I’ve passed by since then, the people accompanying me say, “Juliane, stand there for a moment, please,” and they take a photo. That still feels strange to me. I find it unpleasant, because for me it’s not a tourist attraction, but a door through which ninety-one people went to their deaths, including my mother. I was the only survivor. And that has preoccupied me a great deal ever since.

That door changes constantly: each time I come by, it looks different. Something new is written on it, or something is painted over. For example, written on it recently was: This is the door through which Jhuliana escaped. Which is, of course, not true. Once the owner of the kiosk heard that she had misspelled my name and the date was incorrect, she took me aside and said: “Now you have to write down your name correctly for me, so that I can do it right.” And those are the moments when everything comes up in me. Have things already come so far that someone can do business so directly with the horror of that time? And then they are back again, the feelings of those days, even if only for brief moments.

Of course, I quickly push all that back down. For people can’t help it, and, of course, they don’t mean any harm. And I realize how deadened I’ve become since then, out of sheer consideration and understanding. Was there ever actually a time in which there was space for my original, unbridled feelings, uncensored by rationality? I was preoccupied with these questions as I traveled on toward Panguana with Werner Herzog’s film crew.

I had not been back to Panguana for fourteen years. Until recently the presence of the terrorist organization Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru in the area had made any trip into a life-threatening risk. Meanwhile, the original houses in which I had lived with my parents had decayed. My father had hired Moro to build a new guesthouse: a wooden hut on stilts, like all the houses here in the rain forest, with three small rooms and a covered terrace. Now I could take a close look at it for the first time. My husband and I stayed with Moro’s family, who had relocated their farm to the edge of Panguana’s grounds, so that they could better look after everything. And the not-exactly-small film crew managed to pile into the rooms of the guesthouse and onto the deck.

How many memories came back up! The river was still the same, and fortunately the forest too had scarcely changed. The calls of the birds that my mother had studied so extensively, the wonderful lupuna tree towering at its 150-foot height far over all the others, the butterflies and other insects—everything reminded me of those years when my world was still intact. I wandered as in a dream through the places of my childhood, grateful and amazed that I could still move in the rain forest in the exact same way I had learned to do as a child. “It’s like riding a bike,” my husband observed, laughing. “You never forget how to do it.”

We went to Puerto Inca, and there we met Don Marcio, who had brought me to Tournavista back then. It was a really moving encounter for me, after all those years. Along with many others, Don Marcio had helped search for the wreckage for the documentary. Once, he had even set off on his own. Unfortunately, he was injured by a stingray. It stuck its poisonous stinger through Don Marcio’s rubber boot and into his heel, causing his foot to swell intensely and become inflamed. Due to this incident he might almost have died in the jungle, if a boat hadn’t passed by. But since Don Marcio had almost no money with him, these people didn’t want to take him along. So out of necessity he offered them his rifle, a valuable item in the jungle, and so they let themselves be persuaded to take the injured man onto their boat.

I’d heard of his bad luck, and bought back the rifle with Werner Herzog’s help. Now we brought it back to him, a small favor in return for what he had once done for me. At that meeting I said: “Don Marcio, you saved me back then.” But he shook his head and said earnestly: “Not I, but God saved you, Juliana. I only got to be his vessel.”

When we were about to depart in the helicopter that was already waiting for us in Puerto Inca, there was a delay. For the pilot had discovered on an earlier flight that the trees in the clearing where we were supposed to land had not been cut down low enough. The stumps were still a few feet high, and that was life threatening. So they had to be cleared again, and only then could we set off.

I’d never flown in a helicopter before, and I found that really interesting. How you can simply rise vertically and hover in one spot in the air—that was extremely exciting for me, as someone who as a little girl had already been more interested in technical things than dolls.

And then we landed there, in the middle of the jungle, on top of a hill. We were a large crew with a cook and macheteros, who helped us cut the path. Some had flown ahead and had already set up a temporary camp with mosquito nets under large plastic tarps. My husband and I got a two-person tent somewhat away from the others, which was a luxury in this jungle camp. All provisions, including drinking water, had to be brought with us, for it was the dry season. And with German thoroughness a toilet was immediately dug as well, a simple pit with an outhouse over it.

To my surprise there was a tremendous number of sweat bees there on the hill. Even though they don’t sting, hundreds of them stick to you, which is very bothersome. All of us suffered from it. The crew was impressed with how stoically I endured this, but that was simply due to the fact that I was intently focused on speaking my lines as well as possible and not having to repeat them all the time. In the film there is a shot of my arm, where these creatures are just romping about. At the time of my journey through the jungle, I did not have to endure this, for down by the stream there were no sweat bees.

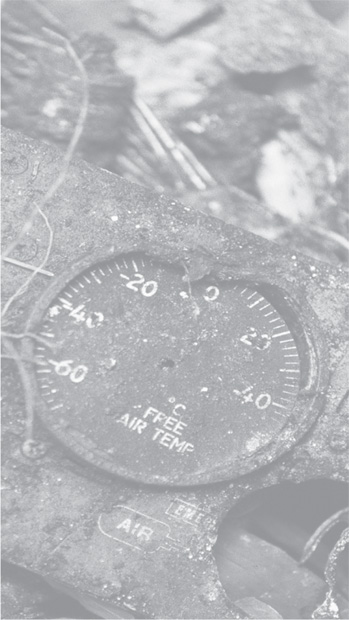

It was a peculiar place, our camp in the jungle. All around us in the forest, the parts of the airplane were scattered. At first they couldn’t be seen at all. Over all those years the jungle had absorbed them. But then, all of a sudden, they revealed themselves, and that was always an extremely astonishing sight—above all, because they were still in such good condition.

We found wreckage that looked as if it had just fallen into the jungle. Since most of the pieces were made of stainless steel or aluminum, all the years in the humidity of the jungle had apparently passed them by without a trace. The rain forest had appropriated them, grown over and around them, pulled them into its ground as if they belonged to it. Often you couldn’t recognize anything until one of the macheteros, who had helped find the crash site, set upright a pretty large piece of the airplane’s sidewall and brushed off leaves, moss and lichens: The paint and writing on it were like new. It was as if I were in a dream.

I saw all the pieces of the airplane in which I had once sat, in which I had crossed the Andes, surface from the green of the rain forest. And yet it scarcely affected me. I found it extremely interesting, even the smaller finds like a piece of one of the trays from which I, too, had eaten my last breakfast before the crash, or the remains of a plastic spoon, a wallet containing coins that had since become invalid, fragments of the carpet on which even the color could still be made out, the heel of a woman’s shoe, the metal frame of a suitcase whose clasps were incongruously still locked while the material that had originally covered it had disappeared. All that fascinated me profoundly, but it didn’t strike any chord inside me. It was as if I were an outsider viewing a distant spectacle.

What astounded me was: The airplane parts seemed so untouched. We also found a propeller and the turbine I had already encountered on my trek back then. And a three-person seat that was better preserved than all the others we found. We assumed that it could be the one with which I fell from the sky. It also fascinated me that airplanes were flying over us. We were exactly below the flight path between Lima and Pucallpa. So the pilot back then had not even tried to avoid the storm.

To see the stream again that had led me out of the forest and thus saved my life was also strangely unreal to me. The courses of streams can certainly be altered over the years in the rain forest, just as the vegetation is constantly changing, and yet I had the distinct feeling that I had been in that spot before. When we arrived at the Río Shebonya, we came upon a lot of butterflies at one point on the bank, and Werner Herzog had the idea of shooting a scene in which I walk through their colorful cloud. But how to explain to them that they should gather at Werner Herzog’s direction? Our knowledge as zoologists helped there, for my husband said: “That’s very simple! All of us have to pee there now, and then the butterflies will come in droves.”

No sooner said than done. The whole film crew peed on that spot, and that’s how the beautiful scene was made in which I walk through a fluttering swarm of butterflies—a fitting metaphor for my flight, the crash and my journey back to life.

And finally we found among all the wreckage something that did affect me deeply. Again it was initially hard to recognize, even though it was gigantic in size. It was part of the landing gear still lying in the forest with the wheels pointing upward. Lying there like that, it reminded me terribly of the remains of a dead bird, a real living thing stranded helplessly with its feet pointing upward.

I don’t know what people were expecting—whether they thought that I would burst into tears or undergo a powerful emotional eruption. I’ve never been the type for that. On top of that, some survival instinct must have formed a protective shield around me over the years, allowing me to lead a so-called normal life. Today I also think: The shock I undoubtedly suffered during my plunge from a height of ten thousand feet lasted until during the filming. To this day it has not yet completely dissipated. And probably that’s all right. It’s a mechanism that allows us to live with a monstrous experience, to deal with it as if it were a birthmark that belongs to us, a scar, an affliction. Or sometimes even a blessing. Who can decide?

But today, as I look out over the Yarinacocha Lagoon, I sense that the time when I have to keep those memories at a distance is now over. Now the time has come to speak about it. All those years it wasn’t possible. The work with Werner Herzog, which I really enjoyed and for which I am still extraordinarily grateful to him, helped me a great stretch of the way to working through my past. For me, someone who has never gone to a therapist, Herzog’s film work, his empathetic questions and his ability to truly listen, as well as the chance to return with him to the site of terror, were the best therapy. Since then, I have found peace and inner stability. And yet another thirteen years had to pass before it would become possible for me to tell my story more fully than I had done ever before. Werner Herzog’s careful documentation had set the course for that, making it possible for me to write this book today. I’ve put it off for a long time. Today I am ready for it.

Surveying the LANSA wreckage site with the famous film director/producer Werner Herzog, 1998. (Copyright ©1998, Werner Herzog Film)

An examination of the wreckage: the frame of a suitcase and a part of the side panel. (Copyright ©1998, Werner Herzog Film)