‘Board’, ‘table’ and ‘field’ suggest almost infinite gradations in scale, yet they all share the notion of the ‘space apart’ as required by structured games. One also finds formal traits relating certain boards to fields, yet, notwithstanding the common ground, there are significant qualities attached to each.

Firstly, epistemological and experiential frontiers distinguish objects, fields and geographic events; for rather than a continuum, space concatenates distinctive conditions. Secondly, certain formats are embedded between ranges of scale: the graspable board is associated with the hand, and the field is related to bodies in action. Formats clash against dimensional thresholds; fields become unpractical beyond certain dimensions, whereas tracks are conceptually unlimited. Critical thresholds in scale determine the substitution of board games with field games. The same holds true of field games being substituted with track games, with a concomitant replacement of surfaces for lines, complex motions for single directions, converging lines of sight for single ones. The scale in fields is loaded with specificity.

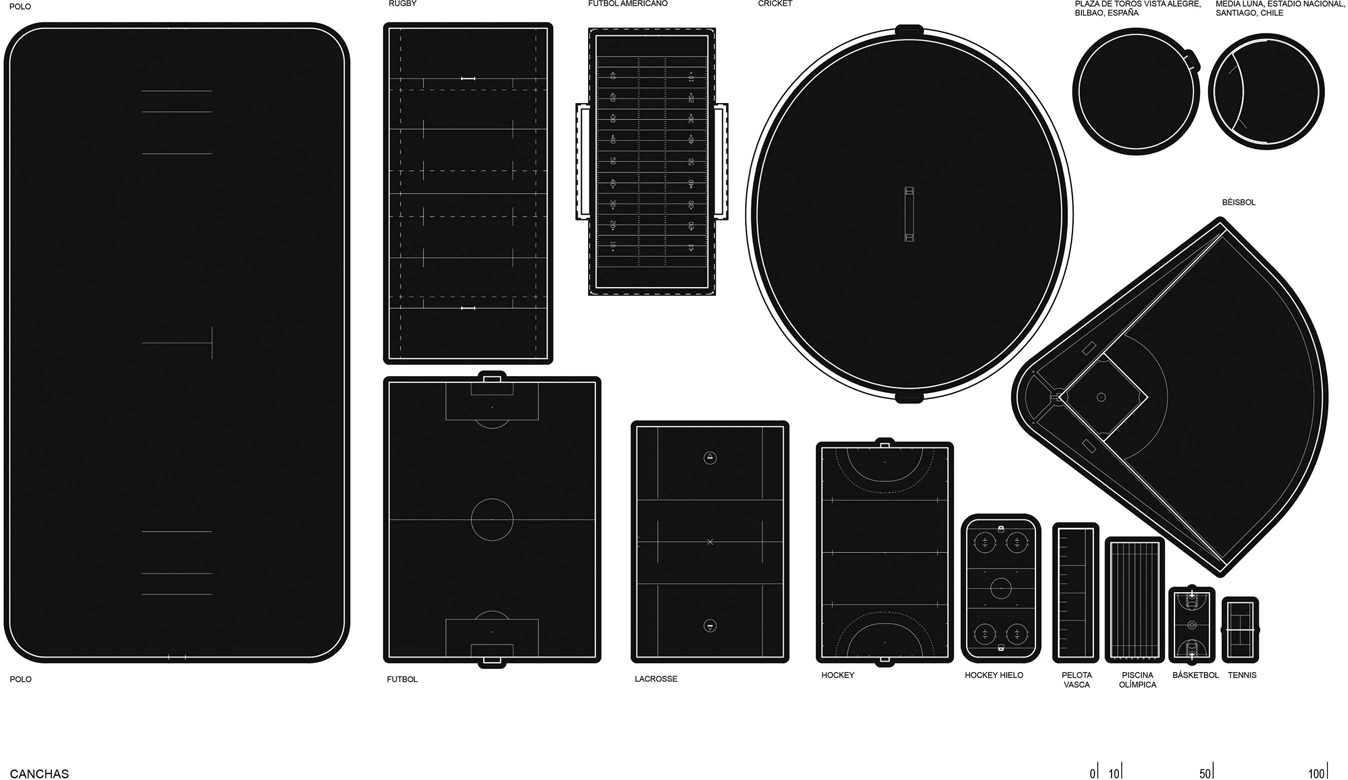

FIGURE 38 Comparative field plans. Drawing by the author.

In sport, orthogonal fields predominate, albeit with significant exceptions; their typical format ensures panoptic control. Each one holds the key to a certain performance: Polo derives its extensive grounds from horse power. The circular arenas of the Chilean rodeo – a contest between horsemen and calf – and the Iberian bullring, betray unmarked field patterns. But there is more to it than mere geometry for each one incarnates a practice in all its possible dimensions. Certain prescribed choreographies, the composition and roles of a team, a rhythm measured in time or scores, cadences, a tempo, and the use of specific implements, all eventually define its contours. Moreover, encrypted notations characterize the modern field, qualifying its areas, discriminating actions and penalties, accentuating its complex, albeit often subdued, topological structures.

As if pertaining to a secondary order of considerations, fields also prescribe the spectators’ perceptual patterns, leading on to specific configurations of grandstands and bleachers. Moreover, the active, even boisterous behaviours that result from partisanship, contrast with the acquiescence to silence that came to characterize the modern theatre. Each score resounds with a roaring acclaim; a reciprocal voice sometimes likened to the Greek choir, for its complicity with the action. But stands also depend on scale and format. Stands can eventually embrace fields, following the concentric patterns of the coliseum, but this relationship is only tenable within a certain range of scales. Upwards from football (in its original and North American variants) it becomes unfeasible to encircle fields with stands. Upwards from polo grounds there are no fields, just tracks, and their stands – whenever provided – are conceived as discrete episodes.

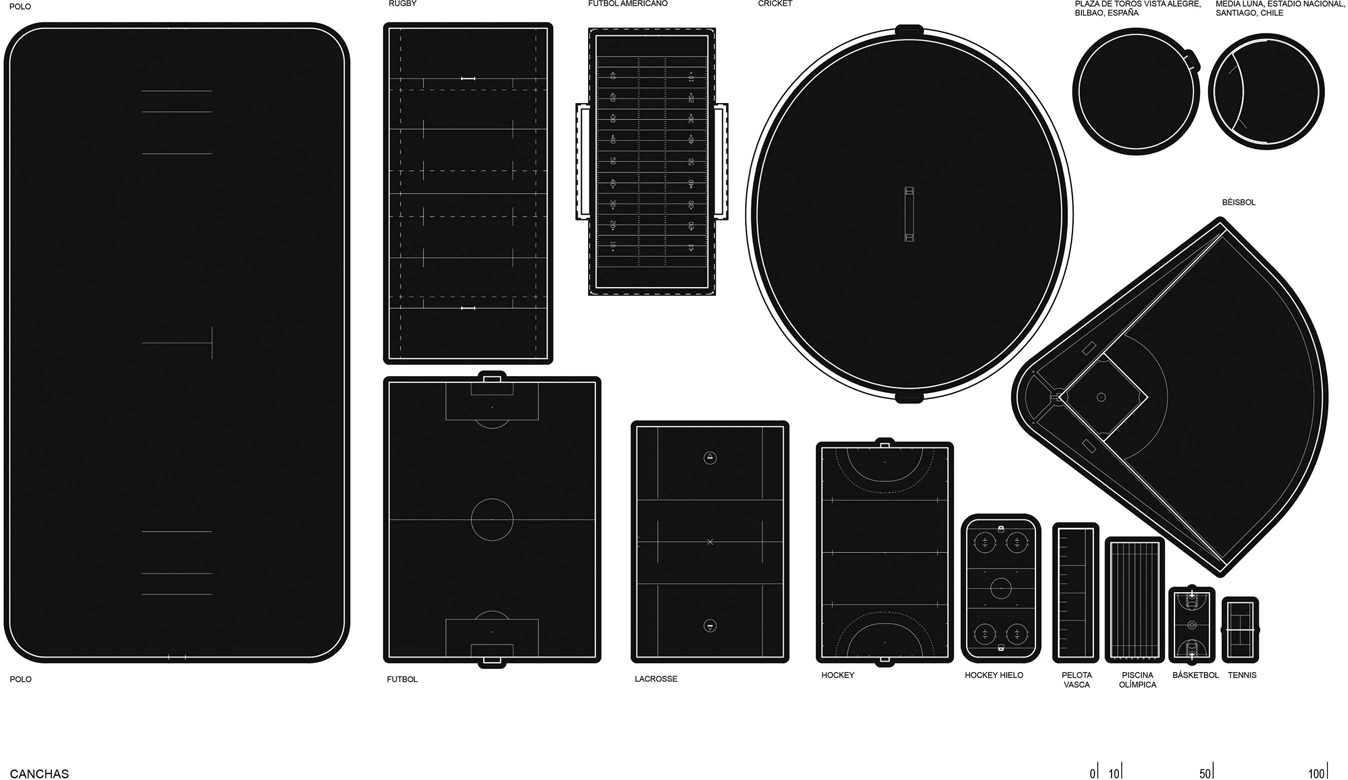

FIGURE 39 Manuel Casanueva: a 3-metre diameter ball becomes the playing field. Teams take turns launching a player towards the ball. Drawing by the author after Casanueva.

Scale rules not only the field but also the implements that must respond to the unique formula devised for each game: balls, for example, may be easily handled. A subversion of scales throws ludic conceptions into utter disarray, as proven by Casanueva’s attempt to re-enchant sport through the manipulation of its formulae.1 Some of his ludic experiments included holding up an excessively large balloon in the air, and throwing players onto the surface of a heavy balloon rendered immobile by virtue of its excessive weight.

Beyond a certain dimensional threshold, the track becomes the only tenable arena. Closed circuits follow different layouts: sprint race tracks describe the smallest range, the horse race a mid-scale, whilst motor race tracks represent the largest purpose-made ludic itineraries.2 Beyond a certain range, equestrian, mechanical and motorized energies substitute human effort. Moreover, layouts are specific to ludic principles and their associated dynamics. Motor courses admit acute bends. Turf settles for generous bends, in contrast with its ancient precedents where the expectation about chariots negotiating around the spina – its median division (often furnished with obelisks and ornamental statuary) – was climactic. The rationale of modern courses becomes evident in the subtle road cambers that counteract the outward pull caused by high speeds, or in the pronounced banking that is common to cycling tracks.

FIGURE 40 Comparative track and racecourse plans. Drawing by the author.

Hippodromes count amongst the largest purpose-made fields. Airports are perhaps the only urban establishments to compete in scale. No wonder, disused airfields were sometimes converted to this effect.

Upwards in length, circuits turn geographical, appropriating road networks, or else opting for the off-circuit, a blurred maze of tracks negotiated over rough terrains. The Tour de France epitomizes the former, the Dakar rally the latter; one embodies the national space; the other is emblematic of the ‘exotic’; both reach epic dimensions. Roland Barthes states:

The French are said to be uninterested in geography … their geography is not that of the books but that of the Tour de France … each year the tour reunifies the country and makes an inventory of its frontiers and products … the combat scenery is the whole of France.

BARTHES 2008

FIGURE 41 Large ludic imprints: racecourse in Rio de Janeiro. Photo by the author.

This concurs with Paideia: through a tactical appropriation of infrastructures, the nation is recast as a ludic field.

These dimensional ranges also affect localization, for they discriminate between that which is inscribed in the urban tissue, and that which can only be construed off city limits. Board, table, and field belong to the domain of design, architecture and landscape, whereas continental rallies exceed design scope.

Quite in line with the agonistic principle, scale also discriminates relational properties. Lacking in spatial depth, the closeness or even promiscuity of the smaller range underscores body language, increasing the psychological confrontation, whereas the panoptic field of ‘active sports’ sets the scene for a whole range of physical rather than psychological rapports, where body contact may or may not be allowed.

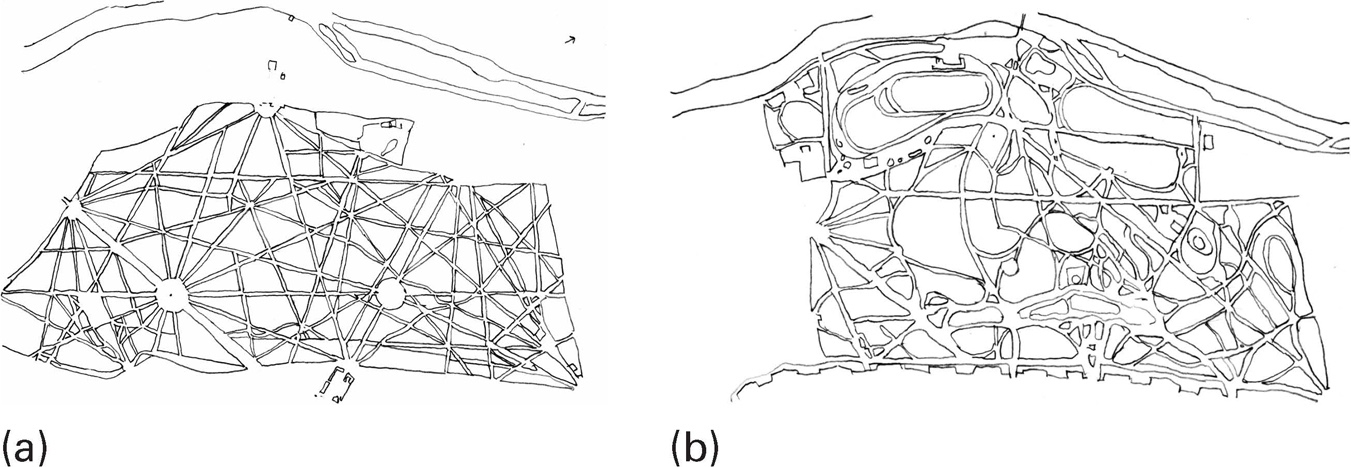

Denoting a large scale, parks evolved in parallel to play practices; the former acquiring a public profile (Olmsted ‘people’s parks’), the latter beckoning education and recreation, as was the case with Alphand’s substitution of the Bois de Boulogne’s hunt rides by a sinusoidal array of promenades, when recasting the former royal grounds into a mixed-use park. Assorted agendas about contemplation and action informed his changes. Lodged within, the Longchamp racing track substituted the former hunt rides for one circuit, thus aligning the equestrian element with modern sport.3 Other fields were incrementally added, until it construed vast mosaics of stadia and courts that eventually covered the southern areas. Lured by the celebration of the outdoors and the festive spectacle, Manet and Degas vividly described its equestrian theatre. Decades later, Le Corbusier fixed his own domicile by the southern edge.

FIGURE 42 Bois de Boulogne: (a) before and (b) after transformation by Adolphe Alphand, executed 1882. Drawing by the author after Adolphe Alphand’s ‘Promenades de Paris’, 1867=N73.

The esplanade, the track and the discontinuous field are recurrent topologies. The former comprises a great variety of materials. Besides size and layout and following ludic requirements, these may beckon such diverse surfaces as ice, grass or hard paving. From a topological perspective, fields that exhibit topographic inflections count within this family.

Defined by a course rather than a surface, tracks describe linear patterns. Although these may range from geometric ones to arabesques, from traces to circuits, a golf course and a toboggan run equally belong to this family, also the maze, except that its course splits into alternative paths and dead ends. Tracks can be assembled in networks, as with the French hunting rides or may assume three dimensional entanglements as with roller coasters.

Connectivity is a topological concern. Certain fields are purposefully discontinuous, heterogeneous and hazardous. Such may be the case with the hunting forest for example, or the aerial fabric of trapezes and bars in the circus. Auciello singles out this trait as one that distinguishes field from board games, for continuity prevails in the former, whereas discontinuities often prevail in the latter where the norm rather than the field regulates motion. However, prescriptions and prohibitions embedded in graphic markings (as with traffic signals) turn fields into heterogeneous entities whilst regulating the scope of performance. Thus, the chess board is made complex through norms that sanction discontinuities within the otherwise homogenous gridded surface; likewise, with fields where graphic markings turn the continuous surface into a highly differentiated patchwork of field conditions.

FIGURE 43 Ludic patterns: (a) Maze at Hampton Court, (b) Go kart race track. Drawing by the author after Alex MacLean.

FIGURE 44 Movement protocols in (a) Ludic and (b) pedestrian practices. Photos by the author.

Terse, devoid of inflections, the level field predominates. Its horizontality is delusionary, however, for drainage requirements induce subtle falls. Its optimal viewing scope turns it into the ultimate stage, thus epitomizing the nexus between play and spectacle. Horizontality enhances the element of chance, and guarantees equal playing conditions. It is often laconic, but as we have seen, its bareness may well conceal heterogeneous conditions and differentiated ludic values, mainly through rule prescriptions. In homologating the players’ conditions, the horizontal surface seems obvious, but even if horizontality appears optimal, the insatiable ludic instinct equally values the ‘accident’. Although all play rules are arbitrary, just a few demand topographic profiles.

A ‘hazard’, defined in the dictionary, is ‘a thing likely to cause injuries’, its secondary meaning is attributed to golf and is ‘an obstacle such as a bunker, a sand pit, etc.’ Hazards may be construed in various manners: through topographic manipulation, by means of built impediments (like steeplechase hurdles) or referring to ground material (such as mud or any other contrivance apt to the purpose of adding difficulty to the motions over a course). Their presence may become as notorious as bunkers in the landscape of golf or the walls, triple bars, or oxers in the equestrian jumping course.

FIGURE 45 Man-made hazard. Drawing by the author after Ortner.

Deriving their ludic potential from the accidents embedded in complex topographical ensembles, gravitational fields construe a concatenation of hazards. Ground materials sometimes act as lubricant accelerating the motions, as it happens with snow, ice or frictionless toboggan walls. But hazards are elements of resistance: a rugged field, an unstable ground, a vertical outcrop.

The ludic interfaces with gravitational forces lead players to testing the world’s physical traits. In this quest, topographic ‘accidents’ became particularly valued: mountains thus attracted prime interest, with the fate of entire ranges ultimately determined by their embedded ludic potentials. Whether for sledging, skiing or climbing, it was just a matter of conceiving them as playgrounds. Either way, morphological properties reverberate in the ludic encounter with the site thus captured, a charged arena resonating with physical as much as psychological challenge.

If smoothness is the required condition for skiing, convoluted topographies are the staple grounds for climbing where the ‘field’ itself becomes just a sequence of hazards. Kwinter notes that a climber, unaided by tools or instruments, enters into subtle engagements with the mountain face: ‘the mineral shelf’s erratically ribbed surface, offers enough friction to a spread palm to allow strategic placement of the other palm on an igneous ledge a half a meter above’. This engagement is no longer within the order of mastering the field but rather of forging ‘a morphogenetic figure in time’, ever alert, an intimate and continuous interplay of every single muscle with singularities. Related to the single contestant, this interface substitutes the always changing figurations of field sports (Kwinter 2002, 31). Following the traditional excursion into the field, which is by its very nature remote, and also forbidding, comes the fabrication of vicarious similes, destined to be suitably grafted on urban places. Henceforth, natural fields and artefacts, the remote and the immediate, lead independent lives, as if splitting up into parallel pastimes. Climbing walls are latter day correlations to traditional climbing in the rough, their folded surfaces and protuberances a rational elaboration of the natural ‘hazards’. So, whilst it stands for the unpredictable, the hazard, an accident, also forges programmed, serialized, artefacts, thus construing unprecedented ludic scenarios.

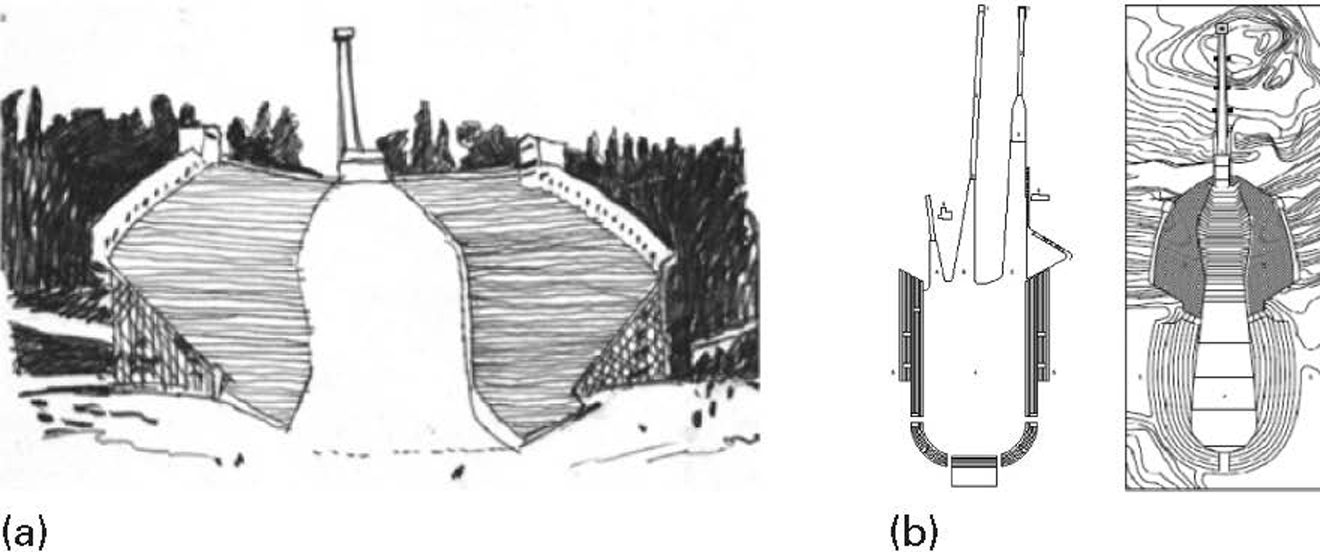

FIGURE 46 (a) Holmenkollen ski jump, Oslo; (b) plan of Gramisch Paterkirchen ski jump stadium, Bayern. © Holmenkollen ski jump. Drawings by the author after Ortner.

Before it became a pastime, skiing was an effective means of transportation, thus confirming that notion of ludic actions as repositories of common practices. Alpine mountain ranges were regarded as natural abominations until the concept of the sublime infused them with the mixed blessings of terror and greatness. Play was no doubt an element in their domestication as it substituted contemplative raptures for ludic challenges. Henceforth their appraisal became tactical; hills were harnessed under the aegis of leisure, with assorted elements coalescing in the ‘winter resort’, a complex ensemble of buildings, mechanical apparatus and earthworks, a perfect seasonal analogue of the summer resort.

Introduced into almost unassailable places, ski lifts maximized use, propelling players upwards with the ceaseless motion afforded by the industrial conveyor belt. Networks of ski lifts and fields were etched over the mountain’s face, as so many scars, turning their surfaces into arenas. Following gradients, and construing particular challenges, each one set a standard. Capricious motions turned them complex, as in slalom, whilst high speed ones led onto nearly straight alignments. Turning rough nature into fields, ludic sensors were thus applied to the mountains’ coarse face.

FIGURE 47 Displacements: (a) Oberstdorf (168 metre); (b) Wembley Stadium wooden ski-jumping hill, 1961; (c) Ski-jump diagram: note that higher profile and elevation correspond to Obertsdorf. Drawings by author after Ortner.

By the nineteenth century, Nordic countries successfully introduced ski toboggans. Reaching up to twenty floors in height, these colossal fabrications, with their alternate convex and concave profiles, set the sequence of inrun, take off, landing, and outrun, casting the skier’s silhouette against the ski. Their emplacement, scale and profile turned them sculptural; their ludic analogues were much like springboards, only just so much greater. Their layouts embodied parametric considerations about form and performance, that were faithfully transcribed to design manuals.

Flanking the outrun, the bleachers construed proper – if slightly odd – mountain stadia, their peculiar bowl shape negotiating complex topographic nuances and lines of sight. In its intoxication with vertigo the experience belongs to Ilinx. Of broad application within the scope of children’s playgrounds, the elementary principle of the toboggan found large scale industrial application before becoming a play apparatus.4

The geometric matrix is dominant within Ludus: it reveals that idea of the field as algorithm, a mechanism of reciprocities between the rule and the material conditions for engagement.

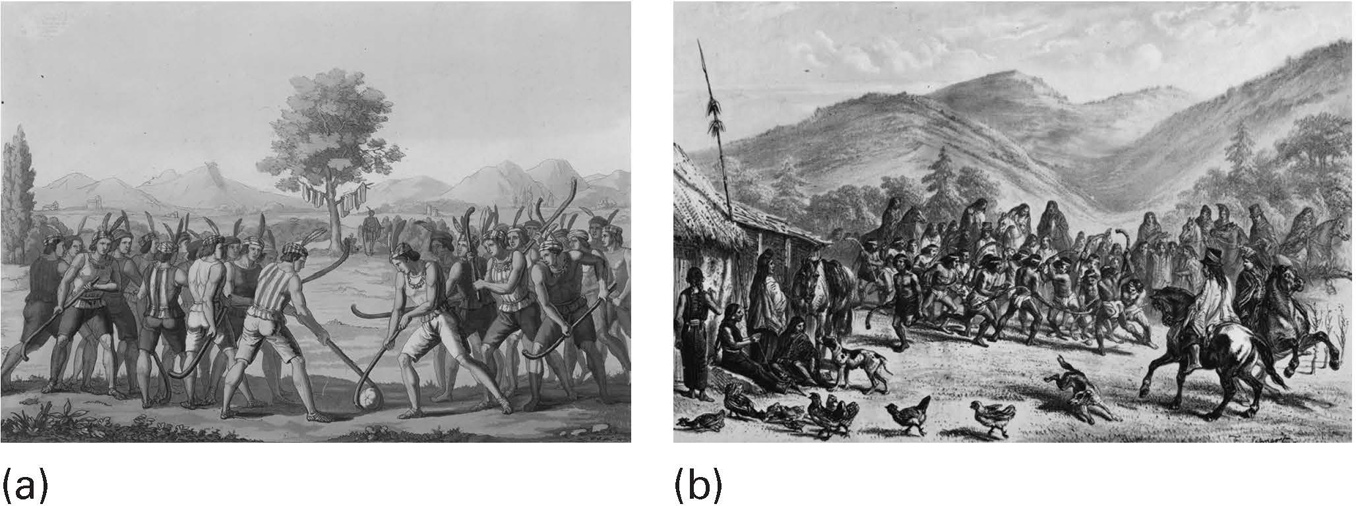

Like most representations of the kind, De Ferrario’s eighteenth-century depiction of ‘exotic’ subjects about to engage in a game was emblematic of the values held by the artist: first there is bilateral symmetry because it is compositionally apt, but also because it bespeaks the agonistic encounter, a fight amongst equals. A single tree enhances it; also, body postures. A classical sense of balance beholds the composition of harmonious bodies. Whilst the recourse to symmetry and balance follows pictorial convention, it also forges the ideal of the noble savage (its Greek or Egyptian ancestry found in identical compositional ploys depicting players about to engage in games that modern interpreters class as ‘hockey’).

The game in question was known by the Spaniards as Chueca for its similarity to the Spanish game. It was played by Araucanians in southern Chile and Argentina with slightly bent sticks, over a rectangular field, measuring about 120 x 12 metres and bounded with twigs or shallow trenches. Rules were kept by heart. Like so many vernacular games it survived through war, oppression and poverty to join the ranks of conventional sports as a token of cultural recognition.5

FIGURE 48 Araucanian games: (a) Guiseppe Erba, Odescalchi et al. Indians Playing Chueca. Image courtesy Brown University. Copyright John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, c. 1821 impression; (b) Claudio Gay, contrasting view in 1854. Image courtesy Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Copyright Common Cultural Heritage Biblioteca Nacional Digital BNC.

FIGURE 49 Rodchenko chess table and chairs: one half black the other red, for a workers’ club, 1925. Drawing by the author.

Indeed, a solemn moment of symmetry characterizes the beginning of procedures: team leaders shake hands, the arbiter sets the game going, until hostilities break. Hence it holds for just one instant. In his nineteenth-century portrayal, French naturalist Claudio Gay was closer perhaps to the facts: all hell had broken loose in the field, whilst the handling of domestic chores as shown in the foreground carried on, unabated. These were common sights, for pre-modern plays shared the casual disorder of carnivals. Elias conceived these changing choreographies as figurations, whilst Huizinga characterized them as engagement and disengagement. As if following a superior rule, games proceed from orderly beginnings to stasis in a dispute about control over terrains, things and time.

Symmetry in fields and play boards is not just a formal convention: quite to the contrary, it becomes an architectural analogue to the Agon … many sacred buildings … are formed around pageants and rituals in which strict symmetry is observed … reflected Rasmussen, recalling the incidence of the procession in the shape of a nave, but such strict adherence of formal structure to ritual is matched in the structure of many field and table games (Rasmussen 1962, 139).

Bilateral symmetry encapsulates the agonistic principle of duality and its correlation in the two halves mirroring each other. It is not difficult to see why it became such a structural device. With its red and black elements in prefect reciprocity, Rodchenko’s workers’ club chess table embodies the concept; likewise, the ones devised by Man Ray, Xenia Cage and Noguchi that celebrated this principle whilst endowing the symmetrical array with a particular expression. As with all components in the making of fields, symmetry is qualified by rules of engagement (List 2005). It expresses itself too as a physical balance that becomes yet another ludic principle, literally applied to the seesaw, an apparatus that draws inspiration from the measuring scale for weights. Carrying heraldic symbols, symmetry also features in playing cards.

When fields are split in mirrored halves players usually interchange positions, following from specific time or sets. Unlike football, however, tennis allows grass, clay, and hard surfaces. Only because players changed sides was it possible to conceive a tennis court with differentiated materials: one with grass, the other clay thus construing the so called ‘battle of surfaces’.6 Symmetrical arrays reverberate in the emplacement of umpires and judges. Medieval tournaments exceptionally set the symmetry axis tangential to the action, hence promoting oblique encounters.7 The concealment of the bodies behind armour, the vibrant heraldry and the clank of metal must have increased the tension and drama, but the symmetrical partitioning of the field conformed to the very same ludic principles as in modern sports.

When the axis cuts across the opposite camps, players confront face to face, some rules allowing territorial invasion, others precluding it; the net enshrines the field’s partition into inviolate grounds, whereas goal posts symbolize the thresholds and ultimate defensive position of a field subjected to periodical invasion. Much like a barrier and a gate, both equally enshrine symmetry, except that one is a deterrent whereas the other rather defines a threshold with the defensive and offensive positions betraying that stylized element of warfare that is present in modern sport.

Elias observed how the transformation of pastimes into sport correlated with those political mechanisms whereby English society (for it was there that these events took place first) solved conflicts without recourse to violence. Fields were incubated following those principles, likewise the House of Commons, the United Kingdom’s prime debating chamber, with its distinct layout that contrasts with the hemicycle. The symmetry axis fulfils diametrically different roles in each, for in the hemicycle it follows a hierarchical relationship between the chair, or presiding body and parliament’s rank and file, as if between a speaker and an audience, whereas in the House of Commons the axis bisects the space in equal camps designated as ‘government’ and ‘opposition’. In doing so it substitutes the single focus for a median line, a virtual axis which betrays an agonistic principle, also apportioning equal grounds, as in the playing field. Its format not only induces but it also embodies face to face confrontations. Its spatial and topographic similarities to Monte Albano’s pre-Columbian ball-court are striking: were one to ignore their ultimate significance they could be easily taken to embody similar agendas.

FIGURE 50 (a) The sport arena and the axis of symmetry in Leonidov’s Cultural Palace for Moscow, 1930; (b) Corbusier with Pierre Jeanneret Mundaneum in Lake Geneve, 1929. Drawings by the author after Leonidov and Le Corbusier.

Tinged with historicism, and too academic to be embraced by modern architects, the compositional principle of symmetry was enshrined in the sports field, so that whatever their predilections, they were forced to contend with it in the organization of the outdoors. Both in structure and outline, symmetrical bodies were hard to integrate, for modern compositions largely favoured balance, yet sometimes, architects seized upon the symmetrical matrix of the field as an organizational cue. Le Corbusier’s 1929 Mundaneum and Leonidov’s 1930 Culture Palace in Moscow, drew compositional structure from the field’s matrix. Its function was emblematic, particularly so in the Mundaneum, where it was lodged in a stadium, its oblong plan intercepting a main axis whilst also mediating between residential quarters and the monumental complex of library and university. But these efforts seemed contrived and out of line. It was certainly easier for an academic designer, like the French landscape architect Forestier, to fit sports fields within a park with its meandering paths as he did in the 1924 Saavedra Park in Buenos Aires, where the tennis courts and football ground followed a symmetrical array. Despite the traditional procedure, the insertion of the field in the core of the park was novel: one can follow him squeezing green wedges on the perimeter to keep the semblance of a ‘natural’ space.

FIGURE 51 Symmetrical rigours: lawn and playgrounds in Jean Nicholas’ Forestier Parque, Saavedra, Buenos Aires, 1924. Drawing by the author after Forestier.

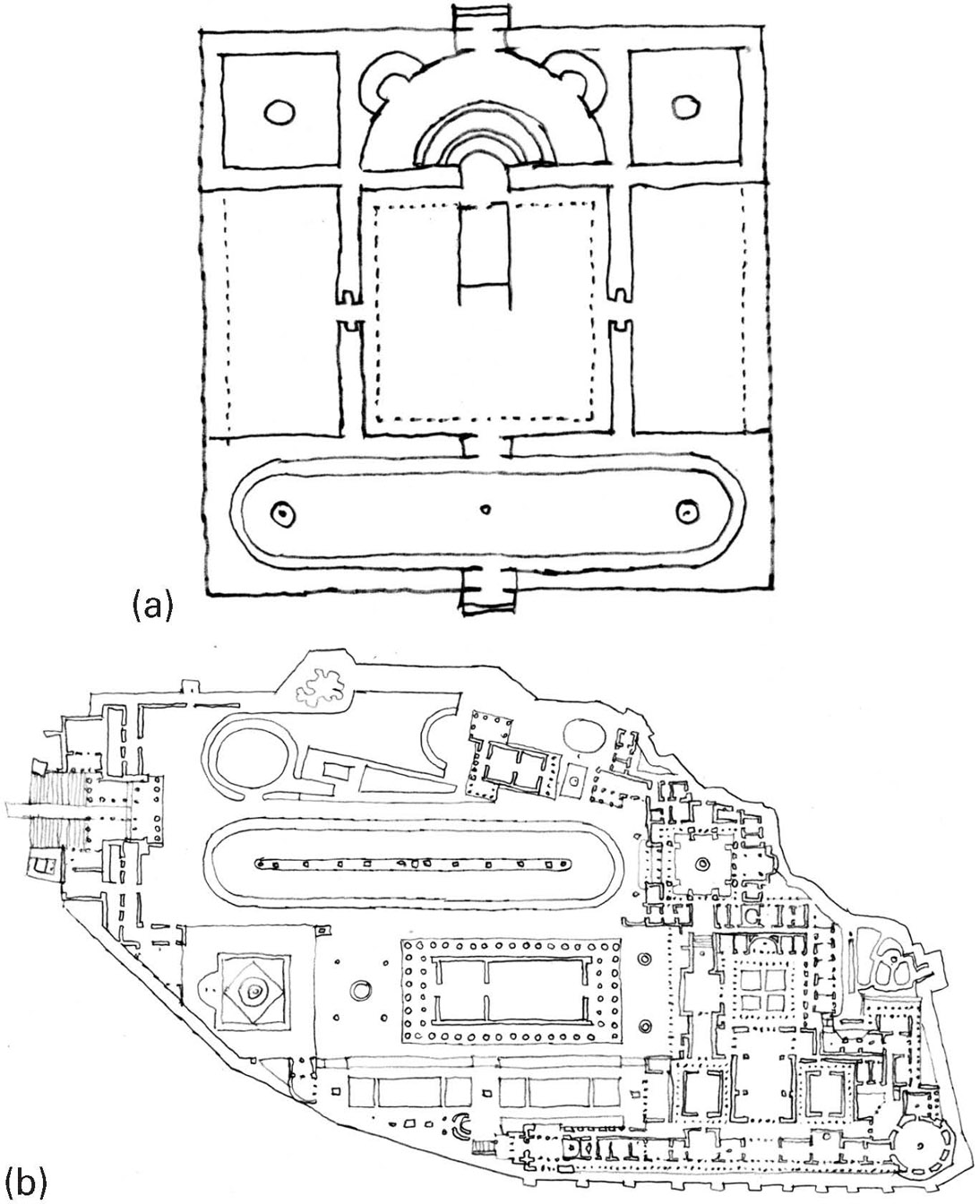

FIGURE 52 Classical hippodromes integrated to larger ensembles: (a) a college by Durand; (b) a royal palace over the Acropolis by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, 1834. Drawings by the author after Durand and Schinkel.

Sports fields were not easily inscribed in parks. Similar dilemmas were present in the framing of hippodromes in institutional ensembles as attempted in the early nineteenth century: their format deriving from the classical precedent with the axial spina and its sharply bent track. Handled by such exponents as Friedrich Schinkel in the Acropolis palace or Durand in a college, these confirmed the pedigree of horsemanship. In comparing Durand’s operation with Schinkel‘s it becomes evident how the inscription of the large field within the tight plateau poses different empirical challenges to its inscription over a flat terrain but besides these contextual constraints they betray contrasting sensibilities about order vis-a-vis an emergent taste for the picturesque.

The perspectival field is also a ludic trope. Golf is a case where ballistics construe linear corridors yet these allow formal tolerance in the layouts of the flanking ‘roughs’. Following linear sequences, fairways articulate changing vistas and naturalistic inflections with straight shots. Likewise, shooting and archery; equally classed as ‘precision sports’, their perspectival ranges do not necessarily construe formal corridors.

The science of ballistics impinged upon military engineering. Military engineering, it has been argued, also informed grand landscape schemes such as Versailles where the arts of Vauban were put into practice for the benefit of representation and leisure: urban historian Gaston Bardet associated urban sight lines to artillery expertise.8

The Hausmannian Boulevard is said to reflect upon military strategy (as with shooting ranges), also to embody crowd management principles and an efficient mechanism for the distribution of goods. We have seen how its matrix derived from French hunting grounds, with their straight rides and round-points. Most likely the Boulevard enshrines more than one design principle.

Be it as cuts in the forest, or in the building mass, boulevards and hunting rides shared precise geometric outlines. The old game of Pall Mall which was also described as a form of ground billiards was played over a lawn inscribed within the geometrically precise alee; likewise, the French pétanque where the field’s format reciprocates in the orthogonal geometries of the formal garden. Modern bowling alleys follow strictly linear patterns, but their serialized ranks result in vast striated ensembles for the parallel deportment of the game.

Formality is in the essence of many a field, whereas informality belongs to the ‘sportive’. It also came to be associated with rolling landscapes and their similes. Of course, biomorphic figures are not any closer to nature than formal arrays, neither are they any easier to construct. As we know, the informal was often attained in artificial landscapes at the expense of massive displacements of people and materials; it was in this respect no more than a conceit heavily propped by rules. Nevertheless, here informal stands for naturalistic, and the value of casualness extolled by the likes of Le Corbusier, Gray and later the Eames, Niemeyer and Bo Bardi.

Formal and informal interplays fuel the ludic imagination. Formal rules determine the validity of certain moves, the range of action of certain players, the definition of a corner or an off side, the sharp distinction between defence and offensive positions, often enshrined in simple patterns. The intelligibility of the geometric field as supplied by its regular geometries and layouts is just one of its outcomes, and yet the informal (also eventually the formless) may become equally necessary in ludic terms. Such is for example the ludic appeal exerted by the terrains vagues, those spaces that Sola Morales defined as … ‘forgotten (localities), mental exteriors, urban counter images’ … (Morales 2002) but also as … ‘promise, space of possibilities, expectation’ … their rampant indeterminacy, an outcome of extraterritoriality enhancing their ludic appeal. Duvignaud ranked them amongst the most privileged ludic scenarios.

Formlessness can also exert intense ludic curiosity. The adventure playground draws inspiration from it, in its quest for transforming – as in a puzzle – the initial chaos into an ordered cosmos. Beckoning the instincts of the bricoleur, it calls for the formless to be ordered, thus realizing its passage to the formal, as is common when playing with sand or snow, where the pliable material is brought into shape through modelling. These ludic dimensions did not escape the attention of architects: Frei Otto propped his discourse on ‘adaptable architecture’ through the evocation of the ludic process. Similar ludic overtones are present in the action-painter interplays with chance (Otto 1979).