Constant Nieuwenhuys, the Situationists, Yona Friedman, Archigram and Cedric Price endorsed the ludic impulse as a prime urban engine. However, nothing could be further away from their respective quests than the mythology of sport. Even less so the earnest conception of play as a tool for the infant’s progression into adult life. Neither did they subscribe to the social agendas embraced by their peers in the heroic period. Tenuous lines connect their somewhat disparate thoughts, but all in all they mistrusted the welfare estate (Price being somewhat ambivalent in this respect). They endorsed the ideas about Homo Ludens as a modern agent, also state of the art technology as a liberating tool, with an early awareness about cybernetics in the fields of human relations and space management.

Most of them rated fun over play, although to different degrees. Constant, his fellow Situationists and Friedman shared a special interest in Huizinga’s Homo Ludens. Friedman was also conversant with Caillois. Archigram rated boredom as a social malaise. Similar thoughts led Gordon Pask and Cedric Price to craft algorithms conductive to obliterate interactive computer programs subjected to either low demand or excessive reiteration. Agile and transitory, these computer aided scenarios would avert this most paralyzing mood.

There would be Fun Palaces, Instant Cities, atmospherics and interactive environments for the fruition of the denizens of advanced societies, who were about to reach a full emancipation from industrial toil (at least, such was the expectation). The heavy cultural baggage associated with architecture, urbanism and landscape did not find outlets in their discourses. Aside from singular Victorian items that infatuated Price and Archigram, historical precedent was inconsequential. Unmoved by the poetics of gravitas, they rather pursued light, changeable, responsive scenarios. Impatient with inertia, they wanted to accelerate time: Price, Archigram, Friedman and Constant conceived provisional environments; mutant, short lived, allied to an expanding consumerism, ‘expendability’ was a catch word. Far removed from brutalism, they phased out concrete in favour of steel, glass, plastics, fibres, and new alloys. A progressive disengagement from site led their schemes to rise free from the ground, sometimes drift or move impelled by mechanical contrivances, rendering futile any concerns about locality. A renovated nomadic experience now fostered by technology became a common ground. Fun and hedonism were far removed from earlier concerns about how to productively fill ‘free time’. Leisure thrills could now be attained by interacting with disposable software.

One would be hard pushed to find sports fields, scout clubs, children’s playgrounds, let alone schools, in Constant’s New Babylon, Friedman’s Ville Spatiale or Archigram’s Instant City. You just needed plentiful and adequate room for leisure in the Corbusian scheme of things, whilst greater doses of individual choice, plus heavy technological inputs were required within the new vision. Peter Cook argued:

The city … [is] a network of incidence … [destined]… to respond to situations rather than to incarcerate events…

COOK 1967

Inert masses of concrete in Brasilia, Chandigarh and countless lesser settings embodied the kind of ‘incarceration’ alluded to by Cook.

The ludic instinct turned political as soon as Homo Ludens became the role model, for in doing so, it set forth unquestionable urban priorities. The ludic ethos that affected all civic matters was far removed from the educational establishment’s instrumental view of play as a tool. It was equally removed from the medical establishment’s view of play as contributor to wellbeing. It was, needless to say, at odds with the military establishment’s view about play as training. Play was postulated as a prime urban pursuit only because the ludic was understood as the citizen’s prime objective. Moreover, the substitution of working time for playtime claimed freedom as a supreme value: freedom from toil, from the regulated uses of time, from habits, also from the constraints of reason or production.

Paideia was the mode of play that best suited such agendas. Of course, its practice was not circumscribed to children (who were seldom mentioned) but to everyone. Citizens’ play was seen no so much a compensation for work, or a tool for social or physical improvement. It was seen as a prime endeavour, a celebration about newly attained freedoms, the ones afforded by a post-industrial, affluent, fully mechanized society. Such was the message relayed by Constant.

But Paideia was also seen as the means by which to mould the citizen’s urban habitat in a kind of one-to-one Lego game, which was intended to cast massive conglomerates, whilst aping vernacular practices. These were indeterminate, ever changing, and participatory. The price to pay was of course the mega structure with its (undeclared) master designer, its purported flexibility and indeterminacy attainable through the exercise of considerable centralized power. Such views run counter to business oriented leisure initiatives (Disneyland was established in Orange County by 1955) where the ludic was increasingly commoditized, although flirtations with the leisure industry were not at all rare.1 They were equally removed, however, from that branch of the leisure industry that dealt with organized sport, an activity estimated by Guy Debord as ‘at least as repugnant as tourism and credit transactions’.2 It was more like Paideia’s revenge against countless modes, whereby the human instinct of play had been made instrumental, commoditized and eventually denatured. If there was an urban model behind this rebellion it was far removed from those ludic considerations that had borne the foundations of modern projects. Hygienic and rational design parameters were ignored. The social, pedagogical, philanthropic considerations that had thereto guided the criteria for ludic spaces were equally abhorred. Closer to Duvignaud than Huizinga, despite all differences between the respective actors, this particular vision of play redeemed its impromptu character, its Dionysian promise and its rebellious nature.

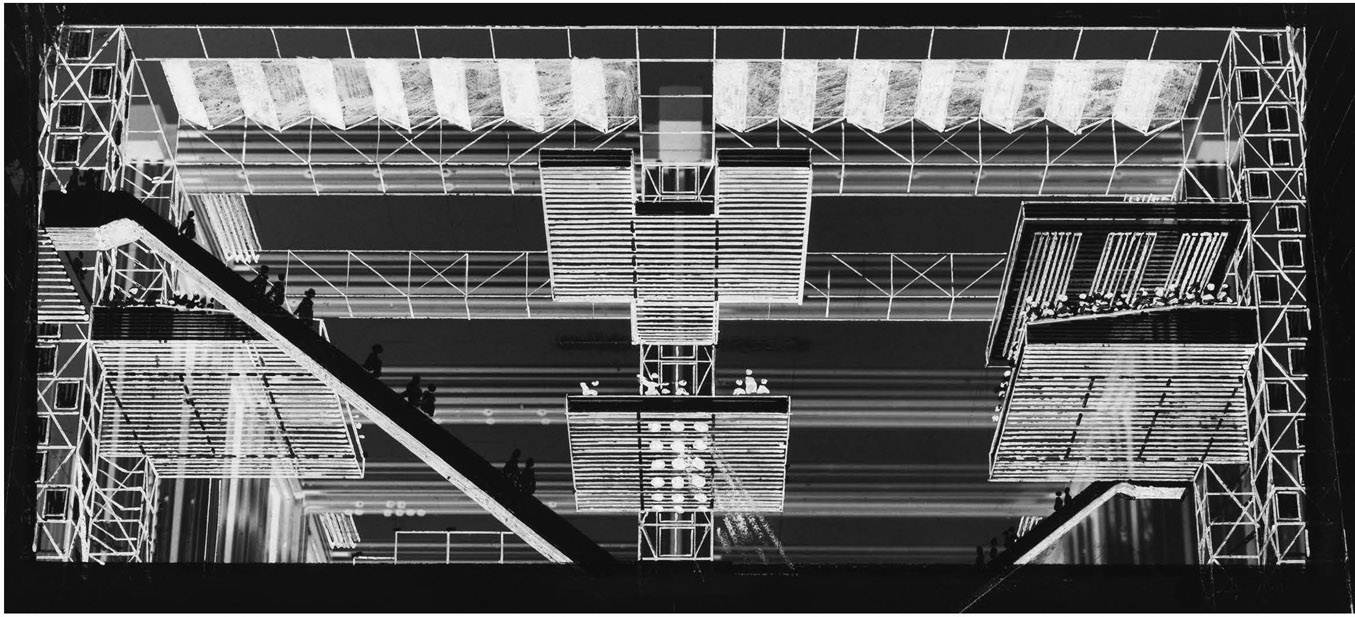

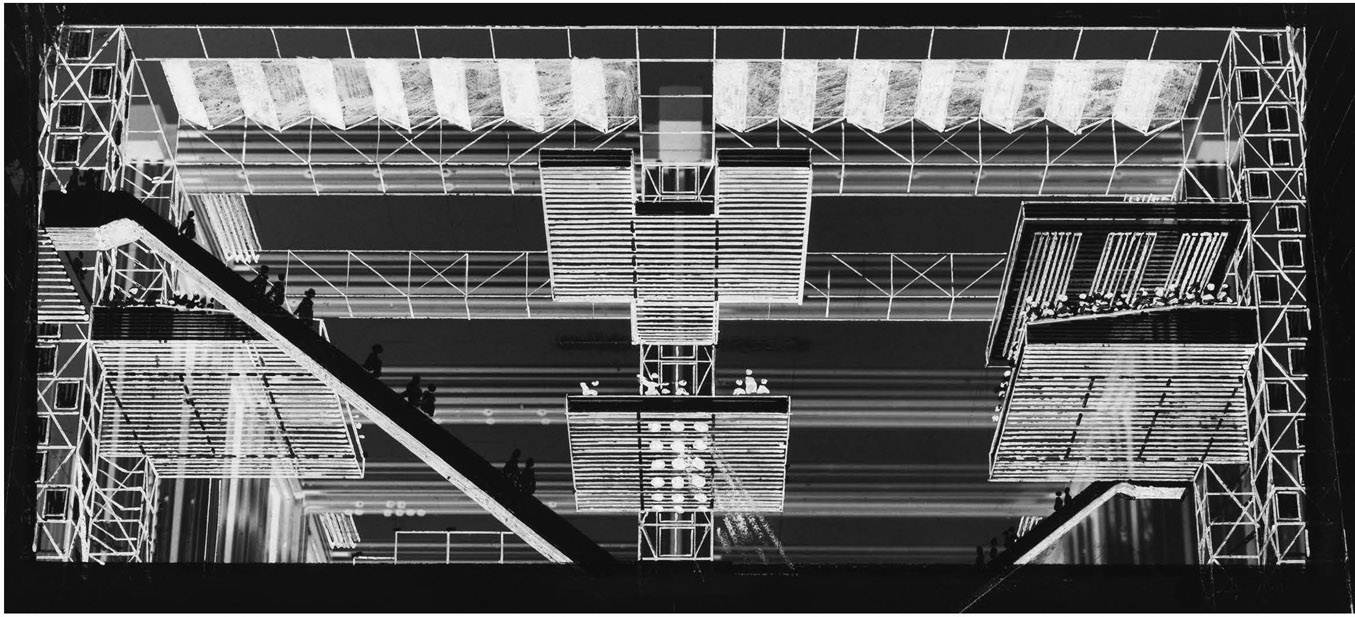

The agenda did find institutional outlets, however. Conceived in Price’s words as ‘a toy’, a ‘university of the street’ and a ‘laboratory of pleasure’, London’s Fun Palace was an attempt to break down conceptual, psychological and physical barriers of the kind that hold leisure and learning activities apart, whilst inaugurating novel forms of urban intercourse as afforded by advanced technology. The scheme’s patron, Joan Littlewood, brought her experience as theatre director and social reformer to bear in the programme of this cultural institution which was aimed to break new ground in relating theatre to the public. Price devised a fixed structure to which moveable elements, services and equipment could be freely attached, placing the emphasis upon performance over aesthetics, tuning building and spatial relations simultaneously, as much as the events and modes of encounter generated by each set. Each temporary scenario was to express volatile social desires. His numerous diagrams attempted to foster the kind of choices deemed essential for the materialization of the idea: he liked conveying the notion of a menu as essential to the spirit of the enterprise. Price visualized in play primarily a potential for intercourse. Ludic interfaces between citizen and structure and the direct intervention upon the urban habitat were aspirations he shared with Constant and Friedman. The full-scale Meccano was in a sense the best analogue for his ludic conception that betrayed technological infatuation, the ludic potentials of form making and the ludic challenges posed by tectonics.

FIGURE 149 A pleasure machine: Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s fun palace, Lea Valley, London. Worm’s eye perspective, 1964. Copyright Cedric Price fonds. Canadian Centre for Architecture.

Nevertheless, other than in garden sheds and adventure playgrounds, direct action of the sort was rare in advanced societies, stifled as they were by regulating bodies and massive environmental and planning legislation. With an emphasis upon urban mechanisms rather than form, the strategies summarized as ‘Non-Plan’ (1969) gathered a bunch of critics and professionals around a principle of space management that challenged planning criteria. Non-Plan enforced an idea of direct action to be tested in selected patches of exception in Great Britain, not unlike the Chinese enterprise zones created in the post-Mao era.3 Launched by magazine editor Paul Barker, it aspired to unleash the suppressed forces of creativity, chance and spontaneity long removed from urban matters. Reiner Banham, Peter Hall and Cedric Price were collaborators. Colin Ward, who was an active sponsor of adventure playgrounds (and who later authored books devoted to children’s experiences in city and country, with a considerable emphasis upon the issue of play), reckoned in it a significant model for emancipated management of space.4 In their view, the expressions of individual desires were stifled by overregulation, yet lurking behind direct expression and the protocols of action and reaction there was an undeniable ludic element.

Non-Plan substituted established urban practices which could be closer in spirit to Ludus (for example those that drew their meaning from expressed rules and regulated frameworks such as found in building regulations, treatises or manuals) with the uncertain creativity of Paideia, its celebration of chance and the unforeseen. We have seen how the Smithsons had already nurtured an urban syntax from the spontaneous outbursts of Paideia. Nonetheless, their ultimate aim was to replace one large scale planning mode for another equally heavy one, whereas Non-Plan defied such overall prospective visions as enshrined in planning practices. It was definitely concerned with the here and now.

According to Yona Friedman, leisure and play accounted for the driving force applied to city making. Following from Huizinga, his expanded ludic framework also accounted for the theatrical, the political and the religious, but in his view, only the social basis of such pursuits guaranteed stable human groupings. He reasoned that the history of cities was no more than a protracted struggle to avoid boredom and inanity. Collective recreation required organization, hence work; work produced fatigue, fatigue called for repose, and repose led into boredom which in turn awoke desires for amusement and distraction: such an extraordinary – and at the same time predictable – cycle accounted in his view for much of the experiences of all urbane civilizations.

In his view, Team Ten had failed to face the unprecedented challenges posed by ‘development’, ‘mobility’ and ‘change’.5 With a generous emphasis on participation, his conception of a mobile architecture would channel those leading forces, productively. The essentially adaptive organism of the Ville Spatiale (1958, 1961) found in the ludic instinct a core concept. He derided agonistic games. These were tainted by lingering memories of ancestral – and now meaningless – fights for food, also by totalitarian appropriation. He favoured adaptive and imitative games and particularly creative ones, such as do-it-yourself or amateur painting, which he deemed fertile in urban place making. Friedman made unsuccessful appraisals of Caillois, and it is clear that his vision of the ludic was impregnated with Huizinga’s overarching notion of play, as much as from Caillois’ distinction about ludic modes and their respective social connotations.

FIGURE 150 The old in the new: Yonna Friedmann’s Ville Spatialle, collated to a Mediterranean village. Image courtesy of Yona Friedman. Copyright Yona Friedman.

The three-dimensional armature of the Ville Spatiale was conceived as an enabling structure to be spatially manipulated at the small, medium or large scale with the purpose of formalizing a living habitat. It aspired to mobilize the ever so latent forces of individual initiative in order to retrofit a high-tech chassis with a new vernacular; such was the game Friedman proposed, espousing his vision in photomontages where lattice structures supported tight dwelling ensembles that could have easily been extracted from Rudofsky’s ‘Architecture without Architects’. Neither shade nor any other effect tarnished the interplay of the suspended over the grounded. Rudofsky reciprocated, portraying the Ville Spatiale as a visionary project that was somewhat in tune with tradition.6 Living up within lattices must have also awoken the thrills of the tight-roper.

Homo Faber the fabricator thus became Homo Ludens the player, for in this vision the utilitarian merged with the ludic, the fabrication of dwelling space (the emphasis was upon dwelling) engaging creative formal games of the kind devised by Froebel. It was as if amplifying Sörensen’s fusion of fabrication with play. But as we know, it was only in small ludic installations where the closest similes to Friedman’s vision were ever enacted, for the expected epic scale was never attained.

Hovering above the crust of the earth, over cities or oceans, unencumbered with hazardous soil conditions or topography, the Ville Spatiale offered ample possibilities for formal invention, albeit always constrained by the fixed three-dimensional lattice. Largely undisturbed, the grounds hosted agricultural space, large scale industrial infrastructure and occasionally, as hinted by the author, massive stadia.

Friedman did in fact test the concept in the Milan stadium with the mega structure hovering over the bowl, its tiny dwelling clusters in command of the spectacle. Years later he visualized retrofitting such places as Place de la Concorde for the Olympics with demountable bleachers and impromptu arenas. Whether conscious or not, he was simply re-editing ancestral common practises.

The substitution of the principle of production for the ludic principle led to the conception of buildings and cities as veritable toys as exemplified in Constant Nieuwenhuys New Babylon (1953–1965).

FIGURE 151 Friedmann’s bid for the Paris Olympics 2004, with a demountable stadium at Place de la Concorde. Image courtesy of Yona Friedman. Copyright Yona Friedman.

Nieuwenhuys and Debord abhorred the Corbusian city and its debased expression in French Grand Ensembles such as Sarcelles, with its multi-storey blocks and extensive grounds of ‘captive nature’ devoted to recreation and play. The construction of situations promoted exploration, accident and an immersion in the guts of the metropolis, with passion, desire, and a full awakening of the senses its main instigators, whilst the principle of Unitary Urbanism radically countered zoning and its deleterious experiences. But aside from the ex-novo situations lodged within New Babylon, the Situationists’ agenda embraced the ludic subversion of cities through ploys such as the nocturnal use of underground infrastructure, the interconnection of rooftops, the elimination of cemeteries and museums, (their contents were to be distributed to bars all over the city), the suppression of street names, and the provision of switches in traffic lights for the individual control over flows. Eminently tactical, and much in the spirit of Paideia, detournement was unconcerned with building new realities as it turned the everyday upside down.

Homo Ludens was expressively embraced by the Situationists, yet Huizinga had fallen short of the real scope of play, they argued, for in his views it accrued value only in contrast to work, as Homo Faber’s alter ego.7 Moreover, Huizinga had paid too much attention to the mores of (Veblen’s) leisure class. New Babylon’s ludic agenda would surge from a classless society once automatic production had overhauled human labour. The scheme culminated in a protracted exploration of the ludic subject, initiated by Constant in collaboration with Van Eyck. His fellow Situationists had taken part in the Cobra Group with which Van Eyck had also collaborated. As noted, New Babylon urban patterns derived from the Smithson Golden Lane diagrams: thus, it was at certain levels nurtured from Team Ten.

FIGURE 152 The play board as a sculpture constant. Neienhuis’s Ambiance de Jeu, 1956. Drawing by the author after Constant.

The urban layouts supplied a fluid and open system in lieu of the dialectics of ‘urban fabric’ and singular landmarks. ‘Units of Ambiance’ rather than districts characterized the urban sectors: these were of course fleeting and unstable as they embodied evanescent conditions. The relentless assault on the senses aligned with Constant’s references to psychological and erotic games.

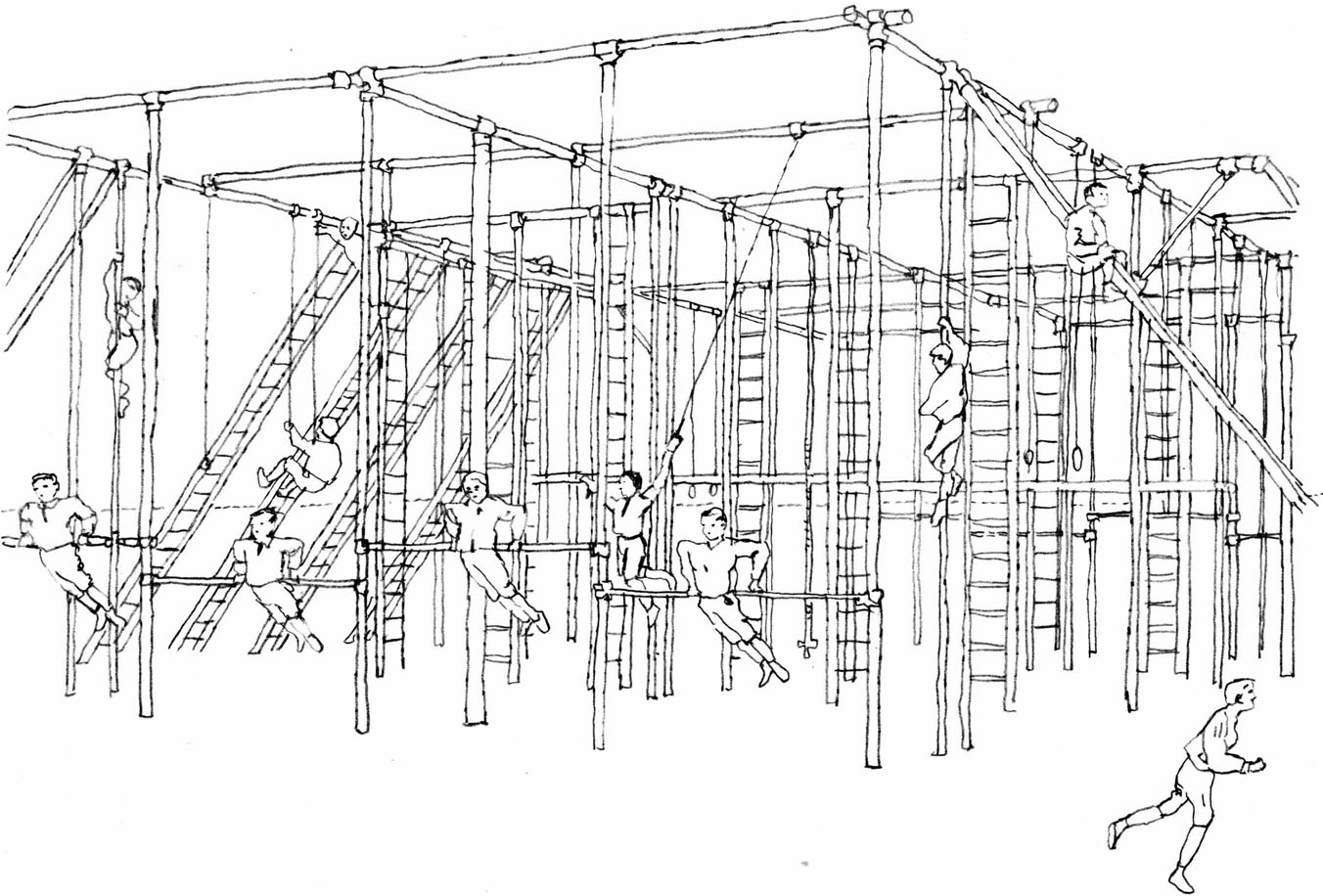

Interaction was critical to New Babylon, as it was with Price, Archigram and Friedman, with the citizens tuning its particular urban effects. The labyrinth supplied another conceptual model, except that it was conceived as mechanical and transitive. Evoking the nomadic life of gypsies and circus troupes, the ceaseless drift in search of novelty would prevent the inhabitants from putting down roots, or forming habits (the latter were deemed undesirable by Constant). In utter contrast with the Enlightenment traditions of intelligible forms of order, Constant’s unfathomable designs induced loss of orientation and memory. But there were other consequences too, derived from the strenuous physical effort required in shaping its scenarios, a point highlighted by Sadler, who equates it to the demands of gymnastics for in an unwritten agenda, the citizenry would require optimal health in coping with their duties of city making (Sadler 1998).

The New Babylon web of interlinked bridges had capsular units clipped on to its levitating urban bulk that reached the ground mainly through some massive load bearing elements. Infused with a spirit best described as immersive, it offered a cloistered experience. The combination of a fully synthetic environment and an overwhelming feeling of enclosure led Alan Colquhoun to draw comparisons with the shopping mall. As is customary in gambling casinos, the removal of play indoors would have led on to a suspension of time, depriving it of the kind of renewed expectation derived from the natural cycles. The relentless derive from one unit of ambiance to another, the fluid and ungraspable nature of the mechanical labyrinth, the absence of landmarks nurtured those feelings that Caillois had classed as Ilinx, claiming the value of subjectivity against rationalist expectations. Of all the authors who delved into the ludic subject, Duvignaud comes closest to its spirit.8

FIGURE 153 Strenuous efforts: a late Victorian gymnastic apparatus. Drawing by the author.

Chance and the unpredictable were underpinned by a robust technological hardware. Specialized software aided the production of ambiances where colour saturation (‘yellow sector’, ‘green sector’), sound, moisture, temperature and spatial arrays construed very particular experiences. The heavy (although largely undeclared) technological reliance did not preclude an equally emphatic call for citizen’s action in the making of what one could term (borrowing from Rudofsky) non-pedigree architectonic formations. Whether disguised or in full view, the mechanical apparatus allowed Homo Ludens to confidently enjoy leisure, but such routine matters as the ones CIAM classed as ‘Living’, and Team Ten with the more inclusive concept of ‘Habitat’, were derided or at least absent from the argument. Bereft of a residential agenda, its plan departed from core modern concerns. Another fundamental distinction in relation to modern precedents was its neglect of the grounds. New Babylon’s programmatic and aesthetic indifference to the grounds applied to their expansive ludic programmes, conceived as prime propellers of its urbane experience. Needless to say, sport arenas and agonistic contests were simply not held within its conceptual horizons.

The aforesaid indifference to the grounds contrasts with the Situationists’ ‘dérivé’, however, with its endless roaming about streets with its pedestrian foundation nurtured from rich European traditions, thus congenial to the urban values so passionately sponsored by Rudofsky, Rasmussen, Rykwert and Jacobs (also shared by countless photographers, writers and filmmakers). Streets and alleyways were the dérivé’s predominant arenas, whereas in New Babylon, such structures were not contemplated. Its robust urban experience was supposed to grow indoors and up, divorced from the traditional urban matrix. Ancestral pastimes were equally ignored.

Invoking pagan ancestries, however, it offered saturated ambiances for the satisfaction of Homo Ludens. Stimuli saturation removed the experience from the ascetic rigours of Ludus. Founded upon the uncertain trails of dérive, detournement, chance and nomadic impulses, the society that emerged from this conundrum would be unable to forge stable forms.

The May 1968 events in Paris were generally considered a turning point. It was the time when Henry Lefebvre extolled ‘the right to play’. The substitution of the everyday for a new order of barricades construed a veritable set of situations destined ‘concretely and deliberate for the organization of a unitary ambiance and a play of sensations’, as defined by the Situationists. Duvignaud equated these episodes to the carnival.9

Leaving aside all considerations about their scope, and political consequences, the network of Parisian blockaded streets reveals a strategy not altogether different to the Danish play streets. Just for a while these exhibited a form of order circumscribed in space, and ruled by particular considerations, as if delineating a ludic space, although with other aims. These nevertheless highlighted certain ambiguities about drama and play. Thus, it is only fitting to close this enquiry with a statement that looked upon play – mainly through its artefacts – in relation to memory and drama: such was John Hedjuk’s 1983 competition idea for the Memorial to the Gestapo Victims on a site tainted with gruesome memories.

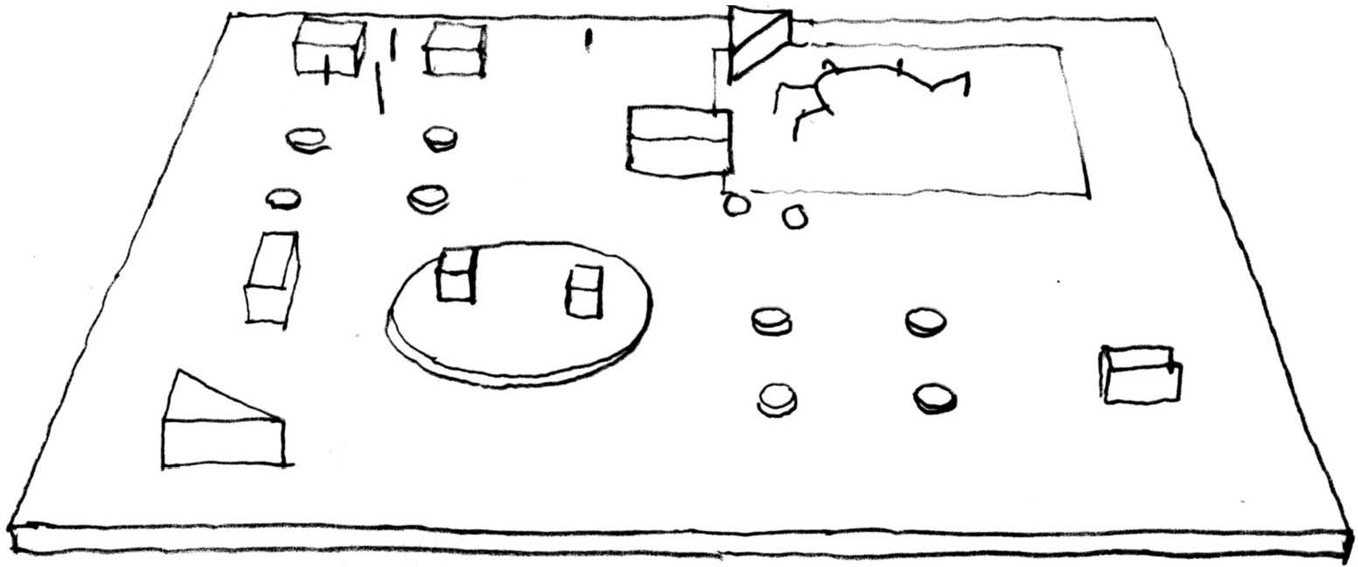

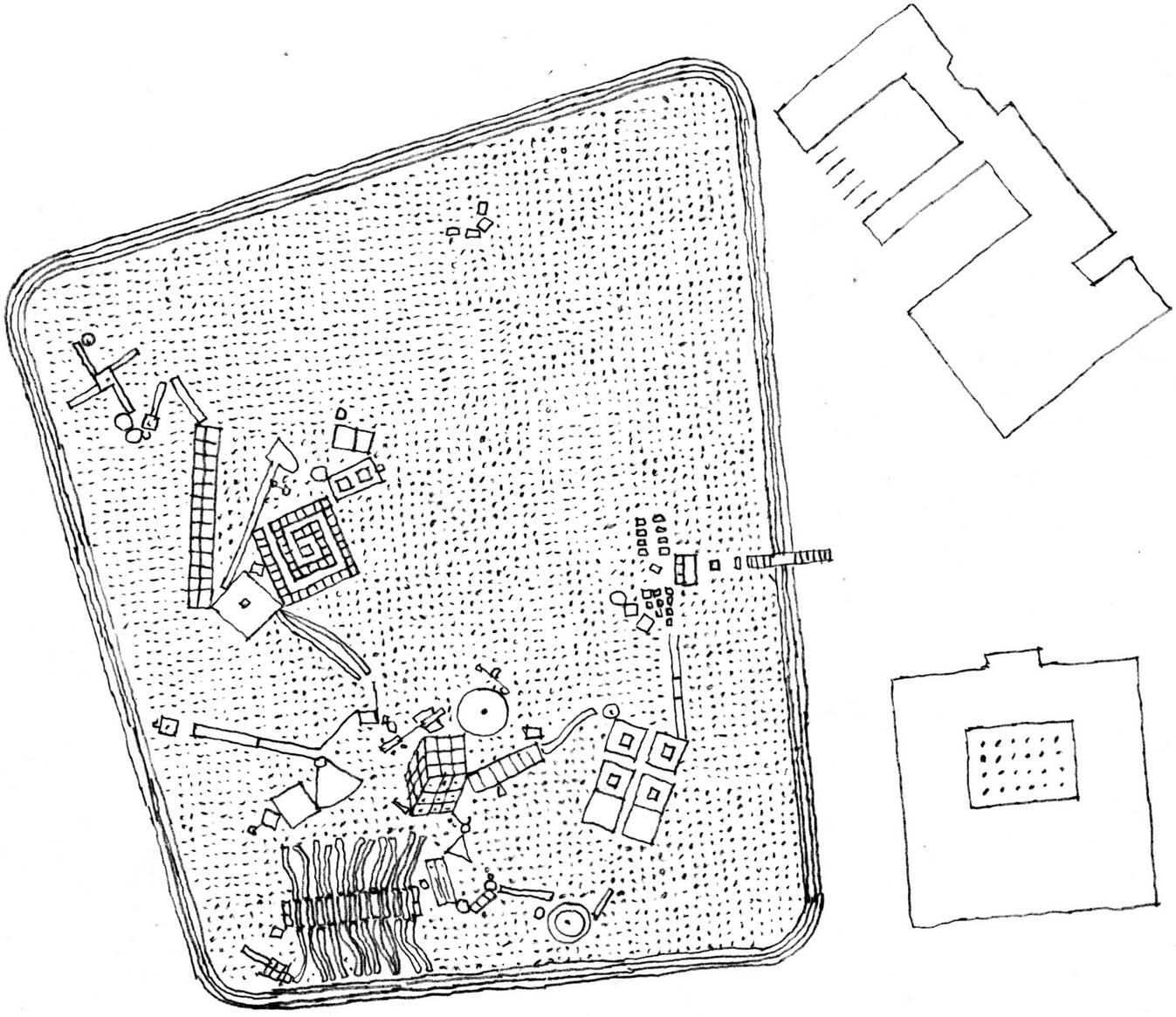

A tram circuit enfolded a vast field populated with assorted objects such as a labyrinth, a ferris wheel, a sand box, tramways, sixty-seven items in all, each one assigned to a user and a particular agenda, all of them immersed in a grove. One by one, the objects were put in place, removing trees as required, the overall process guided by public consultation.

The children’s playground and the fairground were well represented in the scheme, together with other idiosyncratic units drawn from the author’s sometimes bizarre mental stock. Time was to unfold in slow motion, in contrast with Price and Archigram’s accelerated tempo, for Hedjuk drew significant parallels about growth, with trees aging together with the citizen’s passage from childhood to old age.

FIGURE 154 A field of ludic objects: John Hedjuk’s memorial for the Gestapo victims, Berlin. Completion stage with 67 items. Drawing by the author after John Hedjuk.

Referring to the dry orthographic representations and technical mood of ‘Neufert’s’ or the ‘American Graphic Standards’, Hedjuk displayed the full inventory, including sandbox, seesaw, swing, a tram, and the aforementioned fairground wares. Children were clearly expected to fill the memorial with joy, but the impression conveyed is one of a profound foreboding. The ferris wheel offered privileged overviews of the wooded landscape. The absence of clearances in the woods left the space without open ‘arenas’.

There was no technological celebration, certainly nothing approaching a modern vision about technology. Building procedures were simple, if not archaic. No software was summoned, and no techno atmospheres, even though a brooding mood would most probably have pervaded the whole complex. Like Price, Hedjuk supplied a script, except that not as a deadpan ‘menu’, but an ideal one, with a preordained protocol for the assembly of the artefacts. Associated with each pavilion there were characters as in fiction. As regards building materials, timber was favoured above metal, and of course the overwhelming presence of trees bespoke ‘garden’ or ‘forest’ rather than fairground.10

We may ask at this point, why equip a war memorial with ludic implements? Or else, again, what is it that differentiates a playground from a memorial, as we did in relation to the Adele Levy playground. The issue is not innocent, for Hedjuk deliberately conjoined play and reverence.

Citizens could indeed seize the world as playground. Such was the 1960s’ inebriating expectation. But culture had steadily eroded the formal distinctions of the ludic and ritual sites. A similar mindset had impelled Kahn to cast the unpredictable outbursts of free play in solid, inert and durable configurations so that play and ritual met their common origins. Players, the field and instruments (as required) make the necessary ingredients to the ludic event. Each particular player: the child, the athlete and the citizen, captured the imagination of architects who then engendered distinct ludic scenarios that embodied certain notions about society and the city.

The ‘field’ is often a given (or rather the product of a sophisticated evolutionary process), frequently a construct, and sometimes an elusive figure: It is for the most part authorless and X-games obviate it. This late trend suggests a momentous shift away from the architecture of play. When instruments likewise become fields of action, such as an inflatable which is set to roll or glide through human action, no room is offered to architecture. Only under certain circumstances does ludic need lead on to architectonic formulation, however elementary. But as we have seen, even within this constrained framework, the production of architecture of play in the modern period was nothing less than prodigious.