Unburdened with practical obligations, play belongs to the domain of delight. As we have seen, a decisive nineteenth century legacy supplied modern sport, the conception of children’s playgrounds, and the implementation of people’s parks. The latter became a privileged locus for play, quite in tune with its increasing convergence with ‘nature’. With lesser ascendancy, the mechanized fairground or amusement park, made a ludic counterpart to the industrial shop floor. Ludic arenas were attached to educational establishments.

Like many nineteenth-century gridded cities, Aarao Rei’s 1895 plan for the Brazilian Cidade de Minas (later christened Belo Horizonte) featured distinct ‘recreational’ enclaves cast over a super-rational grid: an arabesque-patterned park was encrusted in its very heart, with its meanders adding to pleasure, for here – as in play – the inverted uses of time reigned.

‘The principle of the longest path’, affirmed Nathan Rogers, ‘is the basis of the art of the garden’. Paths thus conceived delayed time, infusing the garden with certain grandeur (Rogers 1965, 133). The race course was the other enclave. It was emplaced toward the eastern fringes, its precise outline following measured distance and turning radii, its ludic imperative aiming for efficiency, albeit with no productive goals in sight. Both denote identifiable ludic forms.

Just over three decades later, Le Corbusier’s synthesis of the urban and the ludic ensnared similar meandering paths with dead straight arteries, whilst relegating the race course to the fringes, as in Belo Horizonte. In his Urbs in Orto, sports grounds and swimming pools were inscribed in the arabesque, even at the risk of disturbing the precarious equilibrium of the bucolic and the Cartesian. No longer exceptional, the park became coextensive with the urban plan.1

The Athens Charter consolidated the triad, park, play and sunshine in a synthesis that found an expression worldwide, however fragmentary; but the privileged rapports between the ludic and the ‘natural’ were soon questioned when challenging the radical artificiality of the playground, whilst the notion of the playground itself became increasingly contested.

The mid-1960s brought the issue of play to a climax, when the city itself was conceived as a monumental ludic mechanism. Then, the bearings of leisure upon the urban matrix became overwhelming, but as we know, this unexpected synthesis failed to materialize, for reality pushed things in quite other ways.

Neither heroic in imagery nor in intent, suburbs were tainted with ludic overtones: ‘an asylum for the preservation of illusion’ in the words of Mumford, (illusion brings us to in ludere, to be in the game), these heavens of domesticity, he argued, were not merely child-centred but based upon a childish view of the world in which reality was sacrificed to the pleasure principle.2 Thus emasculated, Paideia posed no political threat, just urban inanity, for the big game was to be played elsewhere, in ‘human scaled’ towns.

A big bang impregnated all urbanized lands with playgrounds, except that without a grand plan. These were nevertheless intended as significant nuclei, hence much like in old traditions about play in the square. Entangled, the theatres of Ludus and Paideia evolved: abandoned fields accounted for ludic fads gone out of fashion, whilst new configurations sprang up unexpected. Later, X-games superseded the notion of the field.

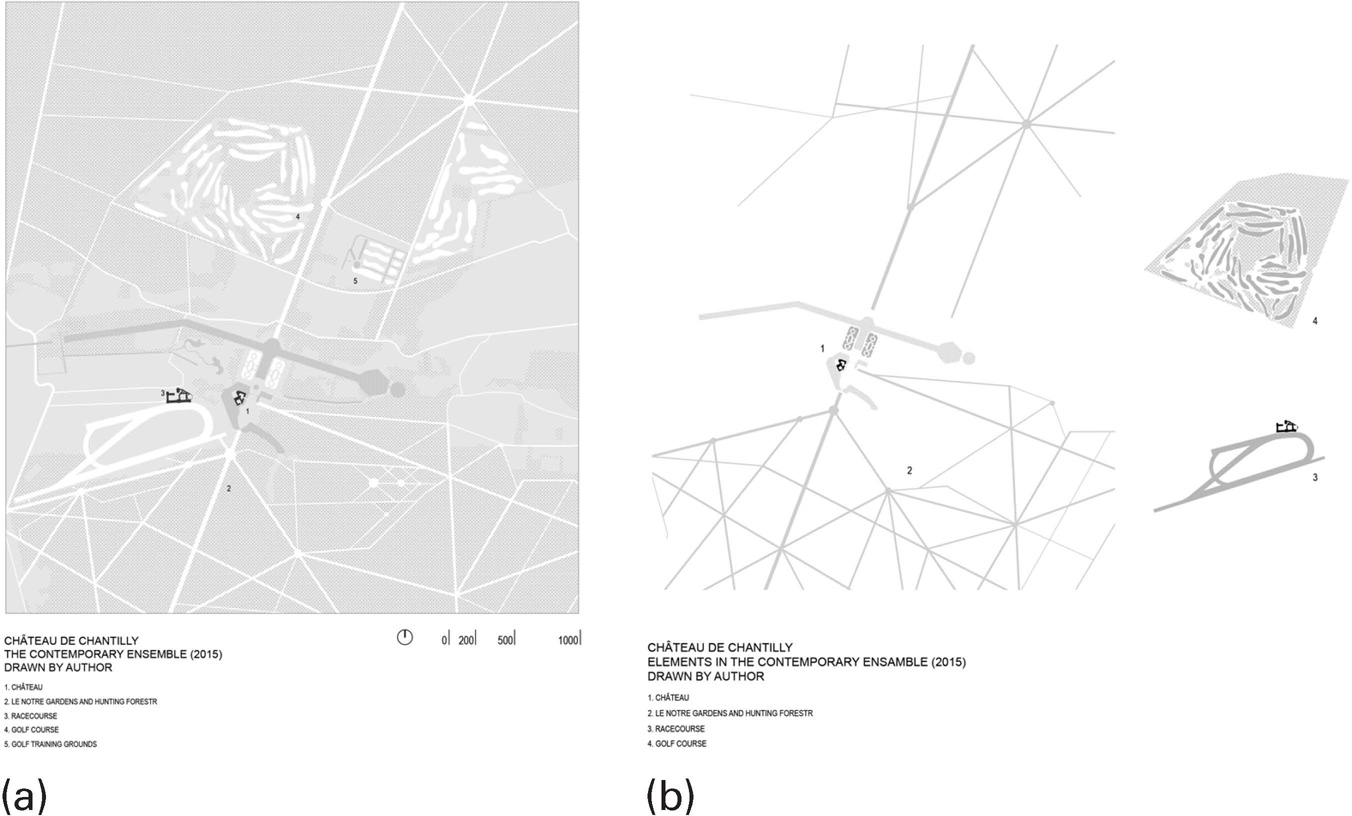

Over time, landscape patchworks interwove contrasting leisure traditions: thus, for example, in Chantilly, Ile de France, long past the baroque climax, the progressive overlay of race course, golf courses, and training grounds substituted courtesan etiquette and hunting. Whilst enmeshing Le Notre’s imprints with embodied figurations of action, hazards, risk and speed, these novel grounds consumed about as much space as the baroque ensemble.

Embedded in greenery, the new lexicon of leisure spaces was in keeping with precise ludic mandates, whilst the various ways in which society catered for Paideia were simultaneously registered. Nearly-proper ‘unofficial’ fields took advantage of urban opportunities across the board.

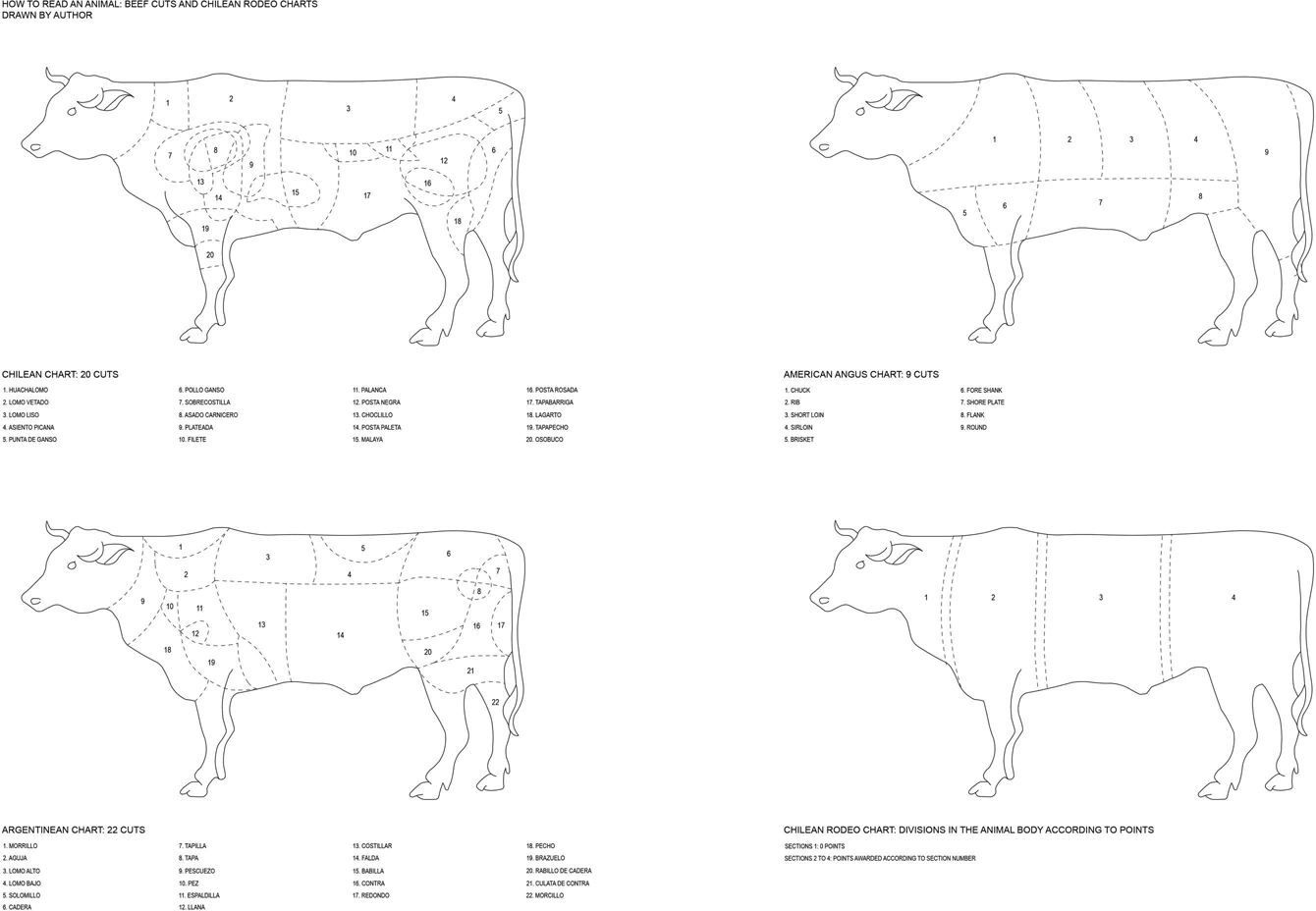

This was a distinct lexicon of precincts, landscapes, spaces and objects, for, within the logic of play, a park could become a garden for projectiles (as in golf), a matrix of platforms (as in sport complexes), a network of impediments (as in steeple chase), whilst a room could become a bouncing apparatus (as in squash), or a climbing device (as in gymnasia), and even a table could be construed as a sliding device (as in billiards) or a bouncing one (as in ping pong). Assuming the agenda wholeheartedly, the twentieth century delivered manifold ludic enclaves, including a considerable amount of green landscapes of a sort that was bereft of ecological variety, with such artificiality and abstraction as one ascribes to industrial materials. These became ingredients of the modern habitat.

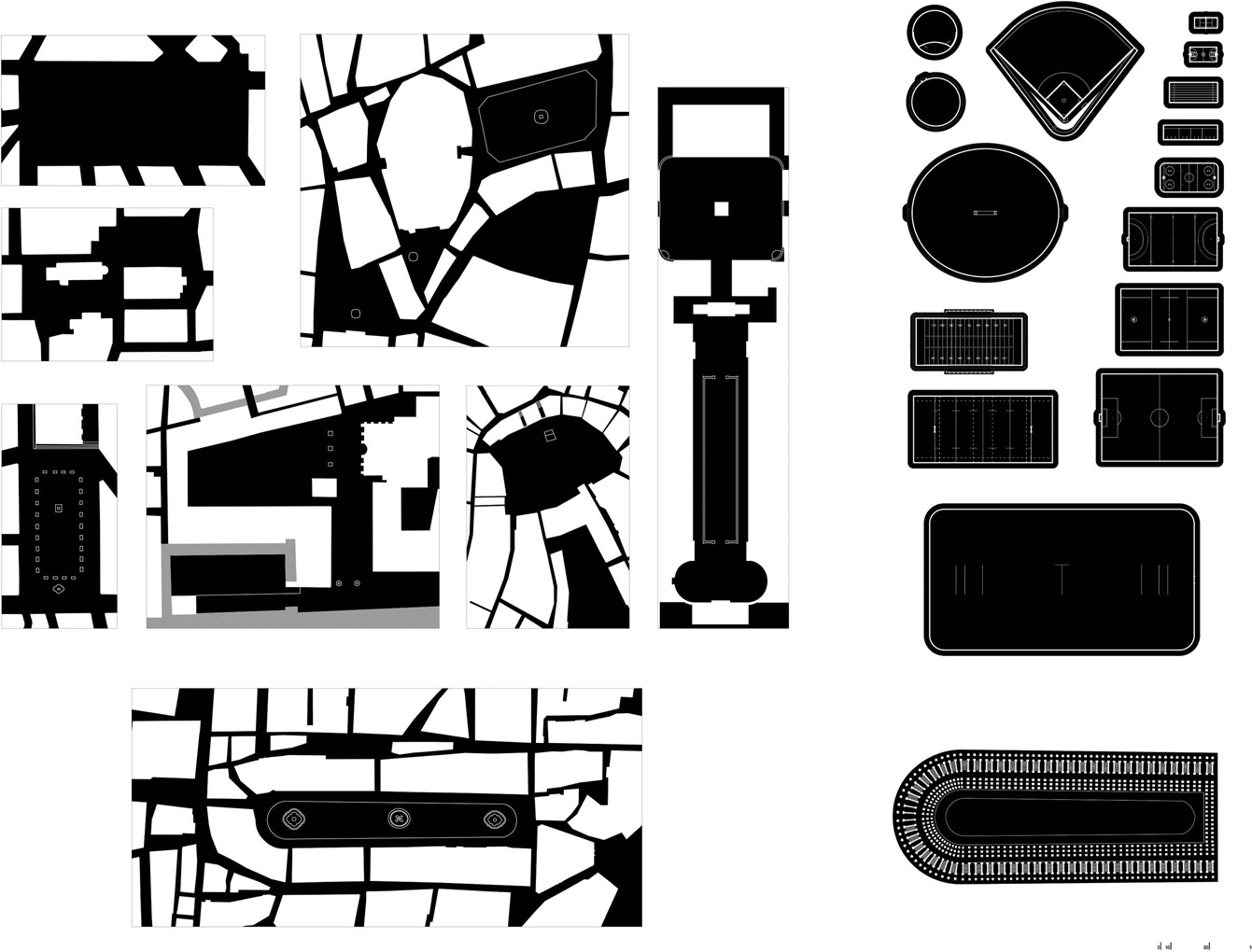

FIGURE 155 Leisure ensembles at Chantilly le Notre’s garden with hunting grounds, the hippodrome and a golf course. Drawings by the author.

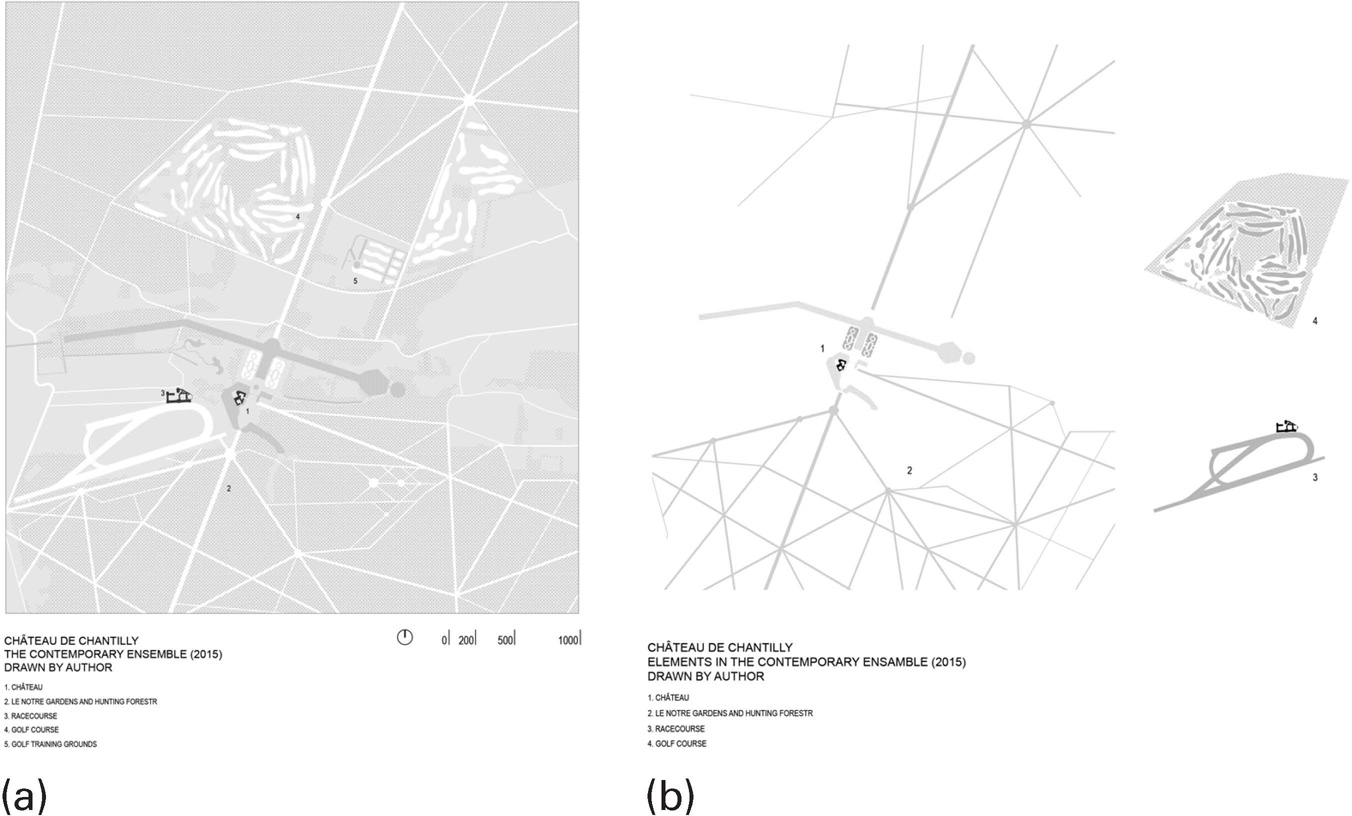

FIGURE 156 Fields and squares. Drawings by the author.

Alternatively perceived as menace or as the ultimate deliverance from toil, newly attained leisure posed new architectonic, urban, and territorial challenges. All these were guided by ludic (that is, entirely arbitrary) propositions; play was seriously considered in the making of cities and neighbourhoods.

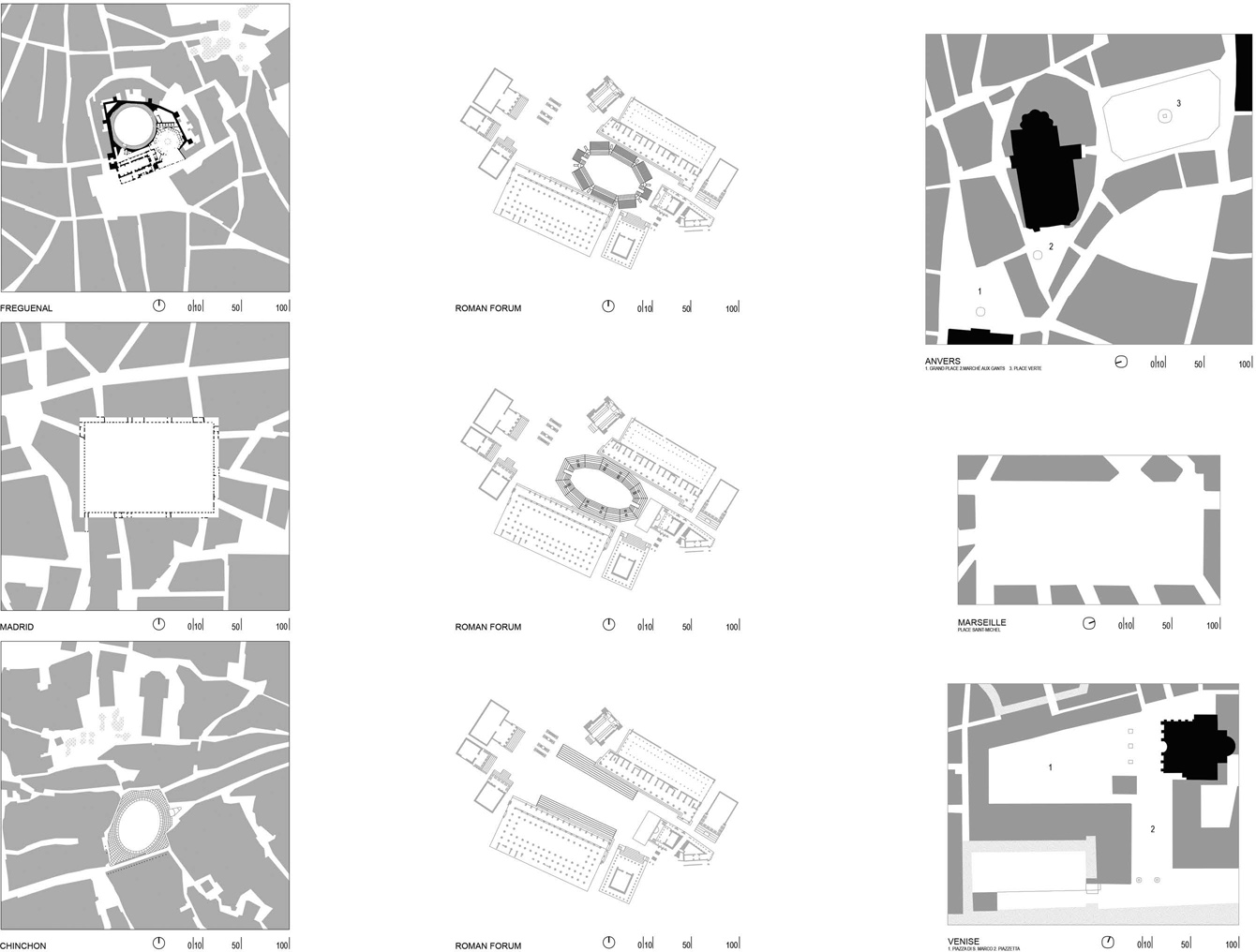

Play is above all a way of reckoning with the world. It is not impelled by material gain, nor by spiritual yearning, but rather by surplus vitality and the pleasure principle. Its assault upon reality is so comprehensive that the ludic instinct affects our relation to plants, animals, minerals, the environment and society in highly specific ways. We have examined how the perception of mountains shifted when these became playgrounds as in winter resorts, but ludic objectives also change our conception of other creatures. So, for example, the mapping of a carcass with an eye for the best cuts, as conceived by the butcher, follows precise culinary traditions, but when play comes to the scene it brings other considerations altogether. Born of rural practices, the Chilean rodeo involves a couple of riders seeking to trap a calf against a circular palisade, so that its arena is mainly used by the perimeter. In this trial, certain body sections (which are mapped as parallel strips denoting areas of body contact) relate to ‘good points’, hence indexing performance. If the butcher’s empirical logic ultimately draws from taste, the ludic one – even within the relative coarseness of rural games – conjoins dexterity with deportment. To the player, the animal represents a challenge as much as an opportunity, hence his (her) ludic appraisal.

FIGURE 157 Mapping the body for food or leisure: Chilean beef chart 28 cuts; American Angus 9 cuts; Argentinean 22 cuts; Chilean rodeo points 4 sections. Drawing by the author.

But ludic aims are insatiable. Just as the animal is mapped in view of arbitrary goals, so we thoroughly map the world we inhabit with ludic intent, only that for the gist of it. Seizing it for play unleashes actions that may or may not last, for not all ludic forms do. Following ludic calls manifold fabrications cater for players and spectators alike, whilst setting the conditions for play. A constant flow of initiatives pushes play into streets and ordinary spaces whilst opposite forces draw it into specialized enclaves. At stake are individual desires and institutional objectives, freedom and control. The issue is compounded by strict differentiations between amateur and professionals, but it is fair to conclude that overall, the twentieth century represents a period of setting play apart rather than fusing it with the flow of ordinary life. Was it a parenthesis or the beginning of a long-lasting trend? It is impossible to hazard a guess but there is one important consideration: if common urban spaces were once possessed as ludic arenas why not try such integrative strategies again?

FIGURE 158 A lexicon of urban spaces. Drawing by the author after Sitte and Sport Manuals.