War had been raging all over Europe when Le Corbusier envisioned fusing the contours of Place Vendôme, the Court of the Louvre and Place de la Concorde (… ‘a legacy of objects we admire whose dimensions and presence are an unfailing source of joy’ …) in a linear pattern of slab blocks (Le Corbusier, 1946, 154). His diagram was of course validating the notion of the ‘redénts’, their apartment blocks folding about open courts. Where the squares would have formerly hosted sculptures or obelisks, he emplaced a football pitch. By 1953, the Smithsons substituted the CIAM charter’s ‘four functions’ (as conceived by Le Corbusier) with ‘forms of association’ that were lavishly illustrated with vignettes of children at play. Embodied in their Golden Lane scheme, the patterns intimated spontaneity and chance. Later still, and inebriated with the idea of Homo Ludens as the true twentieth-century citizen, Constant Nieuwenhuys (who abhorred Le Corbusier’s ‘captive nature’), conceived a city of improvisation, chance and play. By 1972, Robert Venturi incited his peers to ‘learn from Las Vegas’, the Mecca of gambling where the ‘non-judgmental observer’ could learn as much as from Rome. The ludic agendas of athletes, children and assorted citizens became prioritized, whilst play was reckoned as significant as programme and concept. Its entry in the twentieth-century architectural agendas was simply unprecedented, and so were the shifting meanings attached to the subject by architects, planners and landscape architects.

FIGURE 1 A legacy of objects we admire whose dimension and presence are an unfailing source of joy. Corbusier. Copyright Fondation Le Corbusier Copyright: FLC / ADAGP Paris and DACS London, 2017

Play fills our early years with an intensity that cannot be easily matched. Ushering our minds away from mundane concerns, its praxis and spirit as recreation (to differentiate it from performance (theatrical or musical)) accompanies us through life … ‘The child is father to the man’ said Wordsworth.… ‘Genius is childhood recovered at will’ added Baudelaire. More often than not, modern artists yearned to share the child’s enchanted vision: play, we reckon, is by no means solely a childhood affair.

Fascinated with its explorative nature, twentieth-century culture valued its creative and formative potentials. Moreover, it greatly enhanced its visibility through the conception of novel spaces for its deportment. Indoors, the playroom superseded the aristocratic nursery. Outdoors, playing fields sprouted all around. Indeed, play was so highly valued by the fathers of modern urbanism as to endow the modern city with that holiday air that we associate with a superabundance of sunshine and greenery. Play time summoned freedom. An expanded leisure society embraced all. Spare time became a statutory right; Homo Ludens beckoned everyone.

Play has been described as a mirror of ‘ordinary life’. Huizinga, Ortega, Caillois and Duvignaud recognized in play a prime cultural engine: ‘all primordial human occupations’, asserted Huizinga, ‘are already impregnated with play’. Indeed the 1938 publication of Homo Ludens, the element of play in culture in a Europe overshadowed by imminent disaster, heightened the subject, whilst giving it its proper due (Huizinga 1938).1 Yet on the whole, the significance of its setting as essential to the ludic proposition remained unexplored. Huizinga opens up, however, a far-reaching possibility: if play is as central to human endeavours as he stated, why was so little attention paid to its tangible signs? If indeed play creates its alternative world, what kinds of artefacts does it engender? And how are the urban contours of the playground defined?

This enquiry is above all about the play-ground, a particular space released from productive ends in the pursuit of festive plans; about its emplacements, configurations, material description, and equipment. The issue is not so much one of ‘frameworks’, ‘scenarios’ or ‘backdrops’, as one of interplays and entanglement with place, space and matter. It involves, therefore, the unveiling of the singular – perhaps privileged – rapport that binds play as action with architecture as ‘support’; it enquires about how these are forged, and about how these may become embedded in ludic practices to such a degree as to render it futile to extricate one from the other. It emphasizes how play manifests itself through artefacts and space.

FIGURE 2 High altitude field near Uyuni, Bolivia. Image courtesy Christian Juica © C. Juica.

The subject has been extensively explored from such focused perspectives as ‘child play’ or ‘sport’. In surveying the developments on the playground, Ledermann and Traschel delineated fundamental ideas about its structure and spatial requirements only that focused upon children; Hertzberger grounded his ideas about play in evocative architectural descriptions, whilst claiming an uncommon urban primacy to it, yet again his interest was unstructured play. Both Bale and Teyssot looked into sport’s cultural, political and spatial dimensions, whilst Cranz described the conflictual inscription of playgrounds (for all ages) in the North American park, embracing thus a broader range of ludic expressions, but with a prime concern for the politics. A body of technical manuals offered detailed advice on ludic ‘infrastructures’. Recent exhibits at MOMA (‘The century of childhood’), Zurich (‘The Playground Project’), Reina Sofia, Madrid (‘Playgrounds’) made substantial contributions to the subject. All these delineate a fascinating landscape of ideas, events and forms; yet without, on the whole, delving in the urban impact of play.

Ours is a broad appraisal, for its scope in time, as much as in geographic range, seeks to disclose the effect of play upon architecture in its manifold expressions, whilst outlining a comprehensive vision (in contrast with specialized ones such as ‘sport’, ‘indoor games’, ‘child’s play’). In doing so it aspires to bring into architectural consideration the range of ludic concerns raised by the likes of Huizinga, Caillois and Duvignaud.

Why review it now? Considering the subject from within a historic framework may help reinvigorate notions about the public sphere, whilst adding lessons about its rich ascendancy of forms, grounds, and occasions. Play adumbrates public space memorably, charging it with cultural significance, whilst displaying it as freer, its inherent gratuitousness counteracting the excessive bearing of economics in our lives and outlooks. Moreover, cities always knew how to accommodate it: why not look at its settings anew? Our modern forebears procured to extend ludic rights to everyone; is it not worthwhile to resume their quest?

No doubt, play and architecture imbricate. Within its modern understanding, however, one can hazard just four – material or conceptual – links.

Play was understood as a rhetorical trope, a recurrent one within the architect’s discourse: an example is Le Corbusier’s famed 1923 definition of architecture as … ‘the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light’ (play, that is, as expression of the fleeting, unpredictable engagement of form, matter, and light). It was also conceived as a creative tool, a procedural instrument that legitimized the creative function of chance (as with the Surrealists, Dada, and the notion of the objet trouvé).

Play was alternatively understood as a kind of a cradle, laboratory or template of social organisms (a point highlighted by Huizinga, Ortega and Caillois), and finally, it was simply assumed as an architectural programme.

Several interesting traits are attached to each of the above, but the singularity of the latter –which is also the most conventional link – calls for attention, for play had never been so comprehensively understood as an architectural issue before.

This particular architectural programme reckons a binary mode, as represented by play and game, the spontaneous and the structured which accounts for the extraordinary twentieth-century ludic universe. Because ‘play’ embraces ‘game’, however, Roger Caillois coined the more precise terms, Paideia (borrowed from the Greek) for ‘play’ and Ludus (from the Latin) for ‘game’, whilst also probing their mutual transactions.2

Paideia is spontaneous. In the absence of established rules, it rests upon the shared assumption of the illusory ‘as if’: hence upon provisional armatures. Illusion – Huizinga reminds us – derives from ‘in ludere’, meaning ‘to be in the game’. Ludus appeals to a priori agreements and therefore rests upon legal constructs. Both share arbitrary and imaginary assumptions; whoever dispels the enchantment spoils the game and must be expelled; but only in Ludus do rules become explicit and stable (Caillois, 1986, 1967).

Implicit to his analysis, there are spatial matters which he does not delve into, but it follows from his reasoning that Paideia – which is eminently tactical – simply snatches ludic opportunities from any given place; whereas, being rooted in experience, Ludus issues mandatory norms and spatial criteria thus defining its highly singularized fields. Hence, one infers that the relationship between Ludus and architecture is straightforward, whereas it can only be oblique with Paideia. One can also assume that the former is prone to long-term bonds, whereas the latter eschews long-standing rapports. Clubs and global bodies attest to Ludus institutional projections. Paideia might forge strong memories but only Ludus makes proper history.

The submission to the rule bespeaks a social order forged upon shared agreement, hence Ludus also becomes an index of social organization; moreover, only Ludus offers the springboard toward a veritable architecture of play.

Relationships are seamless, however, for Paideia, in any of its forms, may evolve into Ludus and conversely any expression of Ludus may degrade into Paideia. The former’s transit operates through the acquisition of rules, the latter from sheer degradation, when the cohesion of a determined game’s formal armature loosens up. However, Paideia is, for Caillois, the cradle of play.

These fundamental strands of the spontaneous and the organized together with the way in which they calibrate the relationships between chance and the rule become prime ludic topics. Principles and norms ease the institutional life of play whilst also become critical to the definition of a play-ground.

Considerations about the city, the field and the player will structure our argument. The city – the theatre of human comedy and drama – is arguably the ultimate ludic space with the square its prime symbolic locus.3 We will, however, examine the public dimensions of play in a variety of urban settings.

The first part looks into the field as the concrete embodiment of play, examining form, identity and relational properties, its temporal and material foundations, as well as its symbolic and factual severing from the grounds of ‘everyday life’. It also enquires as to how ‘fields’ embody specific ludic principles; hence also how ludic agendas coalesce with architecture. With a certain emphasis on structure and typology, the interfaces forged between rule, form, matter and space will reveal manifold expressions.

Players are fundamental to any ludic proposition: the second part will review modern ludic settings through the perceived urban agendas of three main characters: the athlete, the child, and the citizen. The sequence is by no means gratuitous, for epochal predilections roughly followed broad sensibilities, such as the pre-war cult of the new man (predominantly male and adult), a post-war enchantment with childhood, and certain countercultural propositions that reacted to – amongst other things – the welfare state and the emergent affluent society, opened the field to everyone. Rather than ‘the player’ in the abstract, what emerges from this analysis is a characterization of a certain type of player who embodies certain modes of play. The manner in which their requirements become embedded in particular projects discloses the highly specific responses that leading architects gave to this matter, as well as the distinctive urban status they attached to it.

This generous perspective seems necessary to outline ludic space as conceived between the early decades of the twentieth century, and the crisis of the modern movement, broadly occurring in the 1970s. However uncommon may be the idea about embracing all play types under a single approach, the choice is quite in line with Huizinga, Caillois, and others who thus charted the ludic territory, a fundamental framework to ensure the subject’s integrity.

Play forms reveal social prejudices no less than other social mores, yet one aspect that makes the twentieth century special is its commitment to universal access to leisure, an expanded agenda upon which the so-called leisure industry eventually came to rest, as much as the society of the spectacle. Besides the social distribution of leisure, changing sensibilities about ethics also affect the ludic landscape. Blood sports increasingly encounter public revulsion. Gambling is controlled by law. Statutory limits regulate boxing. No doubt these merit full exposure, but they are not essential to this argument for its focus is instead charting ludic space in modern culture: how the activity takes hold of space; which are the salient arenas and what is the urban incidence. Clearly volatile, this scenario also exposes abandoned playgrounds and disused fields. We will attempt to chart some of these changes, and their urban impact too.4

Much like laughter, play is jovial and unselfish. It thus embodies an idea of freedom. Coercion is simply alien to its light spirit. Freedom and the democratic ideal are at the heart of the leading twentieth-century urban projects; no wonder play finds a prominent place in it. Its gregarious nature renders it congenial to urban space. Its atavistic traits which often embody simple, seemingly immemorial formulations, ease its reproduction.

Just like art, this occupation is lodged somewhere beyond utilitarian experience. Like ornament, play does not fulfil any practical purpose. It neither adds practical elements to the world, nor does it contribute to its progress; at its best it only embellishes human experience. One does not play in order to be useful; one plays in order to move from one level of experience into another, somewhat distant from ordinary experience.

Yet play is often spectacular. Its reiterated practices inform the architectural project which in its turn gives shape to its predominantly urban arenas. It embodies the interfaces between chance and the rule, between the indeterminate and the predetermined that so fascinated modern creative minds. It becomes a sensitive, dynamic and self-renovating index of cultural moods. Much like laughter, its expression is often fleeting and unexpected. Insofar as it represents gratuitous pursuits, it can easily be dismissed as something futile; however, its impact in the formation of our contemporary habitat is considerable. An infinite number of fabrications attest to its tangible presence, but the presence of its grounds which is for us self-evident, was not always so.

One readily recognizes the contours of a soccer field or a baseball diamond, even if in thoroughly unfamiliar localities, but this kind of intelligibility of the play-ground was not always nearly as evident. With the exception of classical Greek and Roman arenas (and here one would need to reckon with the remoteness of ancient ludic practices in relation to modern conceptions) right until the dawn of the twentieth century, proper playgrounds were rare in the West. Until the late nineteenth century playing fields were seldom fabricated, because play unfolded for the most part in shared grounds, thus leaving no significant traces. Even when fields were established, these followed no precise standards. Venice – a city that encapsulates like no other the notion of artifice – exemplifies the case, as seen in the remarkable 1845 Combatti’s plan,5 a detailed account of the city that roughly follows from Nolli’s famous rendering of Rome where such urban interiors as churches or monumental spaces were shown together with the open spaces. The survey does not give away any clues about the subject; perhaps as yet outdoor play did not cast durable imprints. It portrays, however, a singular expanse suggestive of physical deportment, namely, its Campo di Marte. Although clearly not a campiello, nor a forecourt, it vaguely resembled a sports field. Devoted to military drill, it recalled a not uncommon agonistic convergence of military training and playing, but aside from it no formal playing grounds appeared. Did citizens play in every single campo and campiello? If so, one can safely infer that in 1845 Venice, outdoor play did not become as yet an architectural programme; that is to say, it did not call for exclusive configurations. These practices were simply embedded in its ordinary structure.

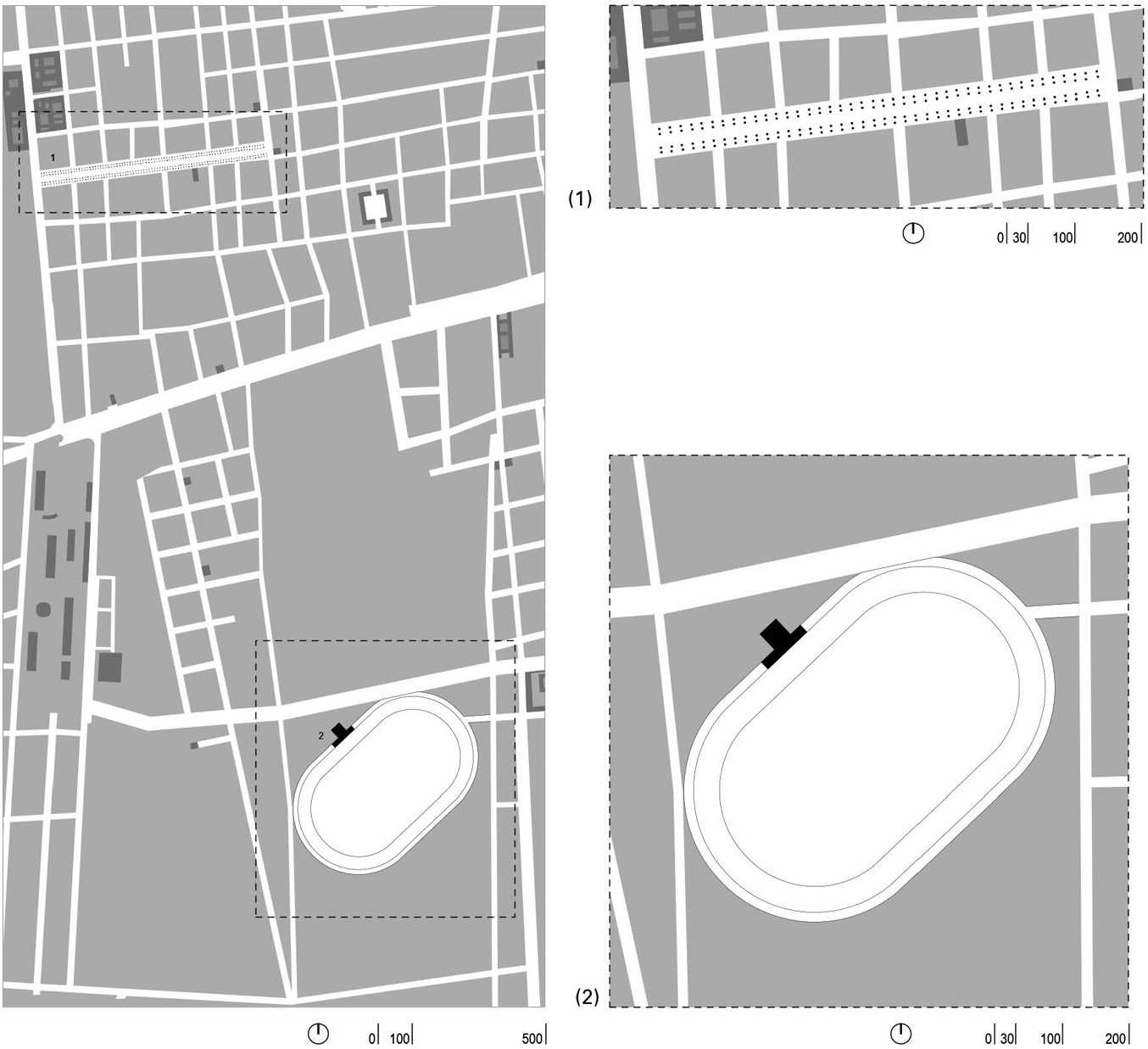

Realized some three decades later by French engineer Ernesto Ansart, the 1875 Plan of Santiago de Chile depicts instead two distinct ludic settings: an extensive hippodrome, and the denominated Yungay race course. The former is a roughly oval circuit that accords with conventional outlines for race tracks. The latter is an alee, with the equestrian field inscribed within the road, a dual identity which is also evident in London’s Pall Mall, Cajamarca de la Cruz’s Paseo de la Corredera, Murcia’s Explanada de España, and San Juan Puerto Rico’s Calle de Cristo, probably too in the French Carrières and Italian Corsos whose names betray equestrian use. Today, these would be termed hybrid spaces.

FIGURE 3 Ansart plan showing: (1) Embedded race course; (2) formal race course (Turf Club, Club Hípico). Santiago, Chile in 1875. Drawings by the author after Ansart 1875.

The early presence of the formal field in a minor capital city is nonetheless remarkable. Santiago was thus equipped with alternative ludic enclaves, the club, essentially an exclusive association devoted to recreation, and the shared space, a public ground accessible to all. Henceforth, whether public or private, the sports field – a space of order, harmonic confrontation and social interaction – became a benchmark.

Just like Venice, Santiago also possessed a Field of Mars, but by 1875 its parade was engulfed in pleasure grounds. It was laid just one block away from the race course, so that together these added up to the largest expanse of greenery in town.

Indeed, the public park, a nineteenth-century invention, was to become a main locus for play. Thus, Santiago’s extraordinary pairing of park and racecourse embodied competing visions about contemplation and action, with their contrasting demands increasingly affecting the evolution of urban parks. Neither of a bucolic nor of a georgic disposition, lacking in compositional or productive goals, the playing field supplied another nature, one that gradually, and not without resistance, forced its way into the park.

Featuring a vastly enlarged cartographic frame, the Blue Guide, Northern Italy and the Alps (1978) embraced an amplified notion of leisure. Besides Venice, its map featured the lagoon. Venice hosted at this juncture at least one football pitch, but day to day outdoor play remained otherwise embedded in its venerable fabric. The outstanding novelty was the inclusion of the Lido – Venice’s renowned resort – and as such its prime modern attraction. It was also a byword for resorts, open air swimming pools, and cruise ship recreational decks.

The nineteenth-century resort represents a decisive landmark in the pursuit of play, a veritable alter ego of the industrial company town, except that where one sponsored production, the other was entirely devoted to ‘recreation’ (Sica 1981). Just as optimized outputs determined the company town’s layouts, the rational deployment of ‘spare’ time organized the resort’s structure, with the beach unfolding as its ultimate arena. Forged around the encounter of sea and land, the sea resort beckoned site-specific modes of recreation: the farther the emplacement from the shoreline, the lesser its significance. The shore gathered tennis courts and gambling rooms – that is to say formal, indoor and outdoor arenas, as if it was an overloaded playing field. (In Spanish, ‘arena’ denotes sand, thus betraying the relationship between place, tactile material, and play, a kind of complicity between the ludic spirit and its material instruments that will be examined later.)

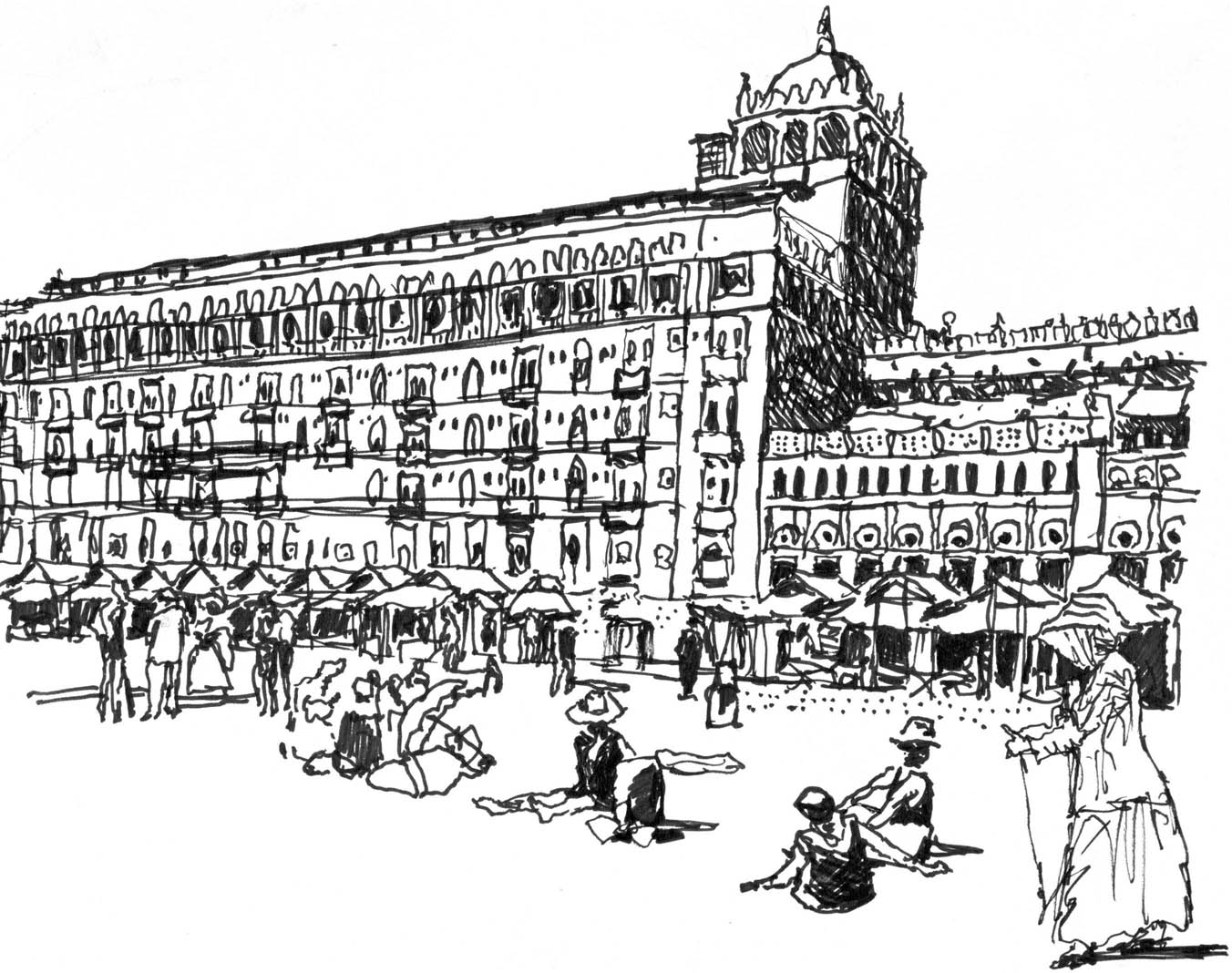

FIGURE 4 Excelsior Hotel, Lido Venice, c. 1910: a palace stranded on sand. Drawing by the author after postcard.

In its prime location, the Excelsior Hotel aped a palace, although with an expanse of sand in lieu of the expected forecourt, as if crude nature had replaced craftsmanship.6 Moreover, the casual demeanours of holidaymakers on the beach contradicted stately manners, not to speak of the utterly subverted dress codes and unprecedented bodily exposure. In the daytime, day guests were encouraged to morph into noble savages, gentlefolk behaving as children or ‘primitives’, only to regain their comportment (and formal attire) by dusk.

Whilst retaining a privileged place in the public imagination, the beach encapsulated a primeval play spirit. In consecrating a particular rapport of nature and city the resort delivered templates for the modern outdoors. It is not by chance that the May 1968 revolutionary claim ‘dessus le pavement, la plage’, unwittingly appealed to this (bourgeois) leisure paradise. Impregnated with an idea of play, this profoundly anti-urban utterance adhered nevertheless to that strand of play that seeks fulfilment in nature. Its implication was none other than the dismantling of the urban crust in the pursuit of leisure, play, and untrammelled freedom.

The unlikely agenda about recasting the beach inland was embraced by Le Corbusier in his 1930s Ville Radieuse roof tops where a sequence of synthetic beaches would have brought the spirit of the resort to the urban heart, enshrining a cult of heliotherapy that conjoined informal leisure modes with the beneficial effects of the sanatoria, whilst sponsoring sport-like trends which would become conventional in the ensuing decades. Some seventy years later, through a massive hauling of sand, the Paris plages scheme softened the Seine’s masonry quays, bringing the resort into the city once every summer. In order to attain these objectives, sand was strewn over the pavements.

The deposition of sand over the hard-urban surface and the alternative uncovering of the primeval (ludic) soil through the dismantling of the urban crust described polar strategies. One operated through material accretion and programmatic densification; whilst inspired by Rus in Urbe, the other made it through subtraction. Beyond these topographic strategies, urban playing grounds also revealed formal and material identities. The modern ones subscribed to an idea of zoning which sponsored the disaggregation of practices that once had shared spaces and facilities. Urban play was largely made to conform to this technique of separation (thus Guy Debord decried its deleterious effects). Zoning was enforced by planners upon urban play, yet players often favoured taking over spaces by stealth: nurtured from spontaneity and self-organization, informality also became a ludic objective. The counterpoint between consolidation of the playing grounds and the ludic recourse to the city at large was innate to modern ludic horizons.

Countering the 1845 Venice plan for opacity as regards the whereabouts of playgrounds, Giacomo Franco’s slightly earlier vignettes clarify the particular ludic advantages attained by Venetians in the Guerra dei Pugni (battle of the punches), a fist-fight contest fought between rival factions over a bridge.7 It unfolded within ordinary spaces. It did not create urban spaces; quite to the contrary, it dislodged routine activities. Nurtured from a certain degree of spontaneity, the game was rendered invisible in maps. Yet it would be equivocal to assume its indifference with respect to its settings for Guerra dei Pugni seems to calibrate Venice’s ludic potential with the utmost finesse whilst deriving its ludic principle from such salient traits as Venice’s structure of canals and bridges. Thus, the keystone demarcated the limit between the warring factions, supplying that element of symmetry in the field common to so many competitive pursuits; its elevation enhancing the drama; it supplied the agonistic frontier, whilst, endowed with the quality of an urban theatre, the bridge framed the free falling dejected parties.

FIGURE 5 Embedded fields, Guerra dei Pugni, Venice. Drawing by the author after Giaccommo Franco.

Hence, Guerra dei Pugni nurtured from Venice’s salient traits. Conversely, it celebrated Venice’s material construction highlighting its dramatic potential. Such reciprocity between play requirements and urban form can best be described as a form of complicity, for it is the case that, whilst players play against each other, they simultaneously play with and against architectonic configurations.

Two ludic templates issue from the above. The first one extracts from the rules of the game such cues as are required for the configuration of the field, and belongs to the domain of Ludus; the other scans the urban field for its ludic potentials, and belongs to Paideia. Such are the possible grounds in which play and architecture reciprocate.

FIGURE 6 Ur Spiele Greek miniature displayed in Kinder Spiel Zug, a catalogue much appreciated by Walter Benjamin. Drawing by the author after Kinder Spiel Zug.

A symbol of urbanity, the square was often a privileged locus for play. The colonial Latin American ‘Plazas de Armas’ were typically characterized as voids within the chessboard plan; they were as indeterminate as regards use, as precise in outline. Together with other colonial enterprises these revealed systemic traits. The Law of the Indies (a set of instructions which counselled orientation, urban layout, and choice of terrain) also betrayed an interest in urban play, counselling a rectangular plan, bearing a one-and-a-half-to-one ratio that was deemed suitable for equestrian contests.8 Even though the format was seldom applied, some authors perceive in the dirt floor that characterized these squares a deliberate ludic choice (hard paved European squares were often strewn with compacted earth for similar ludic purposes).

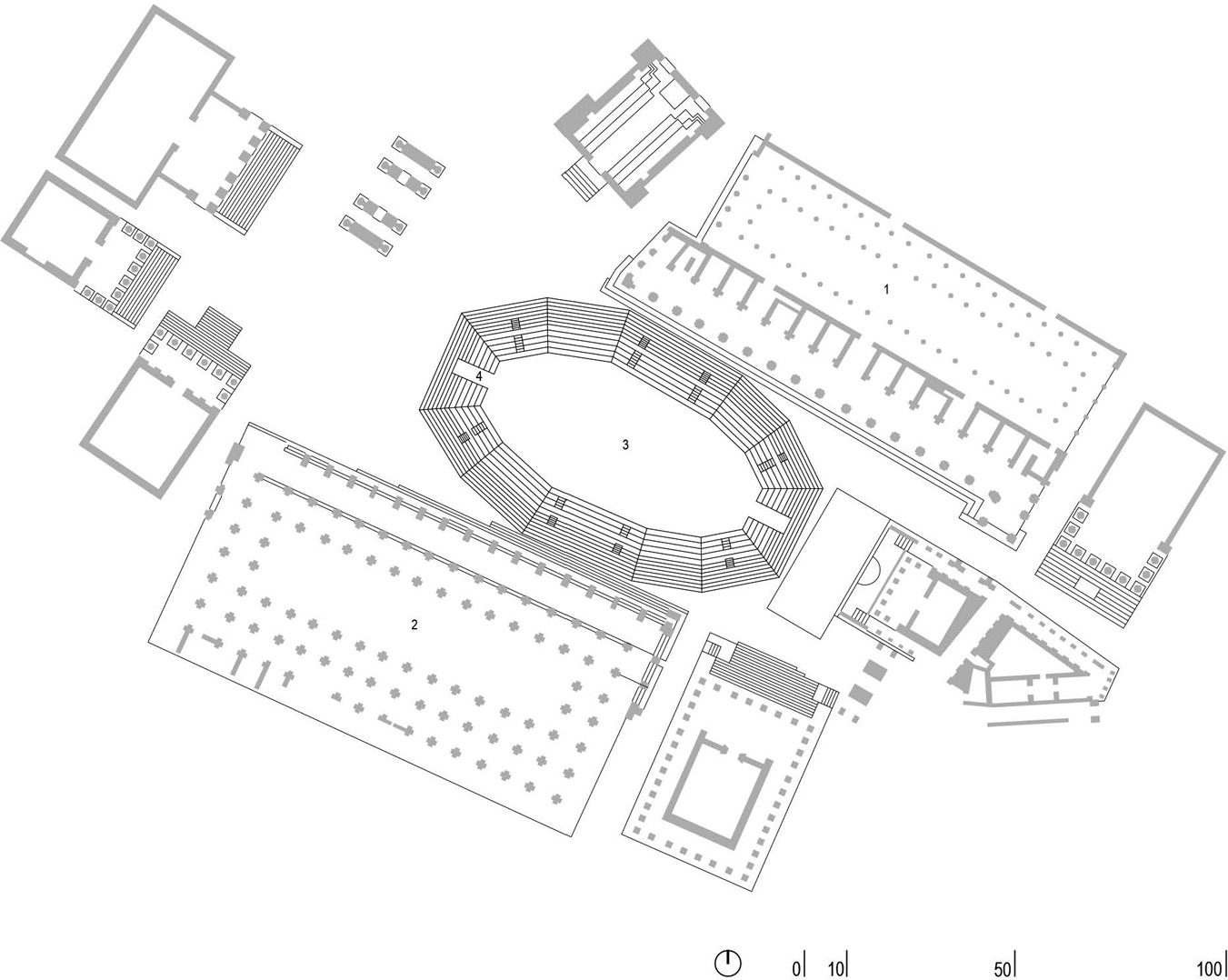

Conjoining ludic and civic goals, these codes followed Vitruvius who had recommended a three-to-two ratio for the plan of the Fora, as convenient for gladiators’ contests, together with the provision of colonnades for spectators. Conceived as theatres, these spaces indeed accommodated ludic functions9 (Welch, 2007).

FIGURE 7 Three temporary arenas in the Roman forum, according to Catherine Welch. (3) and (4) Wooden bleachers accommodating ludic arenas between (1) the Aemilia basilica and (2) Julia (Sempronal) basilica in the Roman forum, 2nd century bc. Catherine Welch, The Roman Amphitheatre from its Origins to the Colosseum, Cambridge University Press. Drawing by the author after Welch.

Whether strictly followed or not, these conceptual frames reveal the metric properties inherent to so many playing fields. Yet besides hosting a plethora of ceremonial functions, the spaces reverted to daily routine, so that a concept of indeterminacy fits them better than exclusive ludic usage. No significant playing fields were implemented in such South American localities until the introduction of the bullring, a building type that evoked memories of the ancient coliseum.10 Otherwise, with minor exceptions, it was not until the nineteenth century that playgrounds acquired the generalized status of proper fabrications, but then the dissemination of ludic arenas became contagious.

Urban space furnishes play with arenas, whilst, through obstinate reiteration, play inscribes its contours in the urban field. Latent in the city there are endless potentials for play, just as latent in ludic practices there are potential field forms. Reciprocity characterizes the interchanges between play and its grounds (which need not be hard: Anglo-Saxon ‘commons’ and ‘greens’ anticipated sports grounds whilst embracing an enduring relationship between public space and cultivation). Soft or hard, cultivated or constructed, fields infiltrated the urban scene, decisively. Play is anything but indifferent to form: more often than not, whether on the board or in the field, it prescribes configurations together with the rules of engagement: contours often contain and prescribe its performance. Such attachment of play to form was prolific in the making of urban spaces, and yet as one can see, urban experts were slow in perceiving its evident impact.

Originally published in 1922, Hegemann and Peets’ The American Vitruvius, an architect’s handbook on civic art paid scant attention to urban play, no doubt because of the subject’s conceptual remoteness from the authors’ perception of the civic, but probably too because the programme did not exude as yet the required pedigree. The handbook just portrayed a few fields in university campus and housing estates. Admittedly the authors’ traditional outlook betrayed their indifference towards play (Hegemann and Peets 1988–1922).

It was not just a question of consciousness, however, for just over three decades earlier, their mentor Camillo Sitte had recalled – although just in passing – how certain Viennese districts contemplated ‘public grounds, children’s playgrounds and athletic grounds’11 (Sitte 1965, 1900). He emphasized ‘sanitary greenery’, as a foil to the ‘decorative’ (i.e. ornamental), hence his sponsorship of the urban park as an institution mainly devoted to hygiene. However, his extensive portfolio of squares did not illuminate ludic usages.

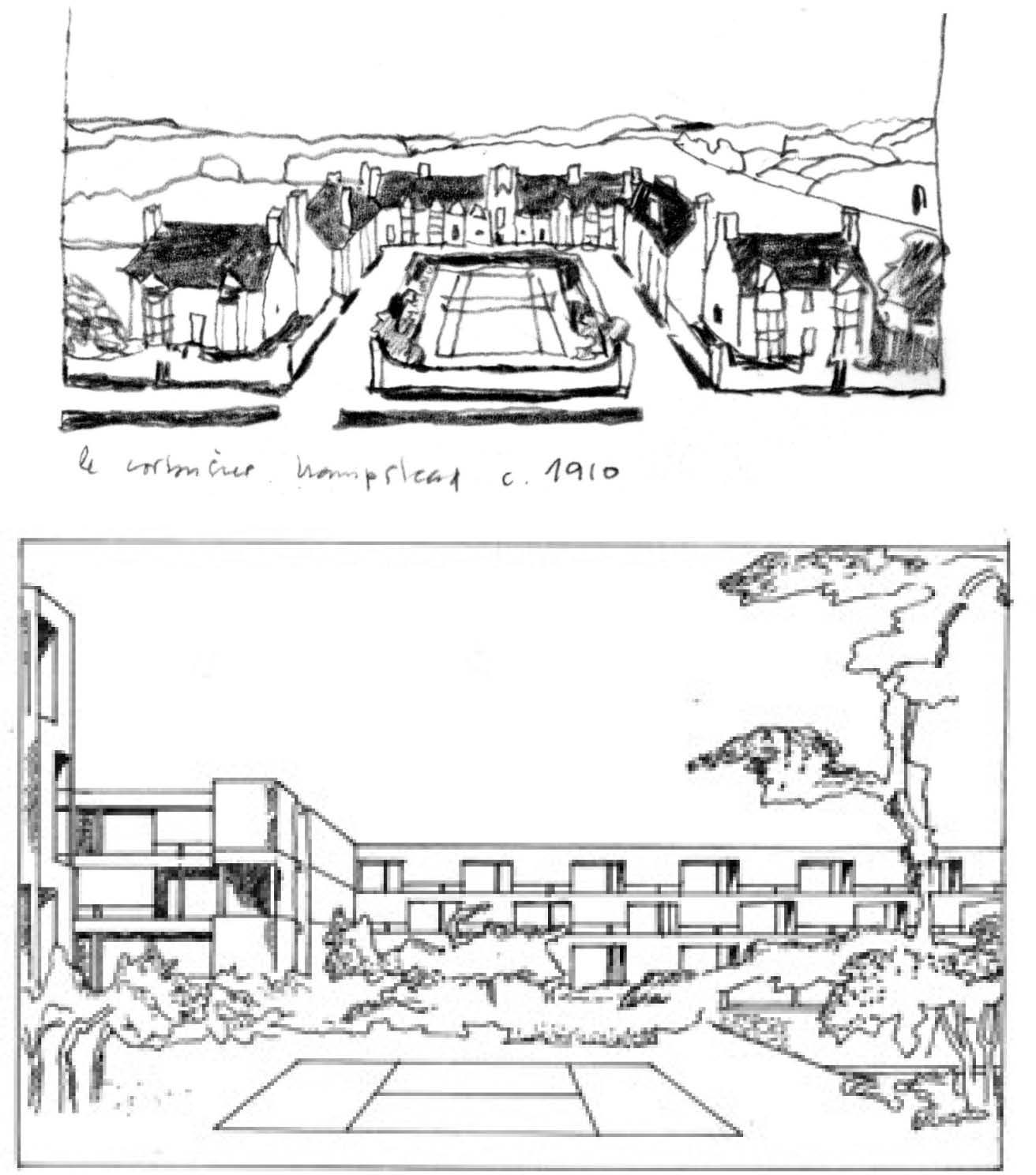

FIGURE 8 Early conceptions about sport in the city. After Le Corbusier’s sketch of Unwis Garden City, c. 1910, and his 1925 lotissements a alveoles Drawings by the author after Le Corbusier.

Not much else was mentioned about the subject in Raymond Unwin’s 1906 Town Planning in Practice either, except for some attention lavished upon the need for safe playgrounds for children and a recommendation about setting parks and playing fields by the edge of towns. He did, however, conceive tennis courts for certain residential schemes, foregrounding Le Corbusier (who sketched up Unwin’s proposition), but overall the ludic subject was alien to his otherwise broad and extensive review of planning options (Unwin, 1994, 1909). As with Sitte, his selected playing fields had little public incidence.

The topicality of play was to take a sharp turn, however, in Le Corbusier’s 1933 Radiant City where play, especially sport, was hailed as a prime subject. Sport, as he put it, was there to be played au pied de Maison, always at hand, and in full visibility. His predicament was congenial to Sitte’s health driven green agenda. His recreational spaces were intended to cater to the hours of idleness guaranteed by social legislation. In view of later developments, his clairvoyance as regards the subject seems remarkable. Implicit in his agenda was the acknowledgement of the playground as a significant urban arena. Similar trends informed Soviet urban conceptions as displayed by Leonidov.

In the course of time, formal playgrounds were either incorporated in cities or else embedded in new urban quarters eventually becoming standard amenities. The countless aspects to be considered about their incorporation would largely exceed the scope of this enquiry, but allowing for some simplification, certain landmarks may be noted.

First, there were ‘bottom up’ institutional sponsors like the club. These commanded the governance of collective events and the planning of new fields. Indoor urban clubs housed sedentary games, sometimes sport, whereas ‘country’ clubs hosted outdoor sports.

Secondly, top-down initiatives percolated from the political establishment that gradually assumed the public recreation agenda within its conceptual and instrumental horizons: ‘the cultural, physical and moral improvement of the race would be a primordial and basic preoccupation of the State’ proclaimed the Spanish Republic in its 1938 Statement of Principles. States devised such administrative figures as a ‘ministry of culture and youth’ (sport, health and education were often allied) targeting site planning, leisure infrastructures, and also vacation colonies where recreation, social welfare and a certain measure of indoctrination converged. Public parks increasingly embraced ‘active’ recreation whilst public housing incorporated playgrounds for both children and adults.

Thirdly, there were the educational establishment fields that aided the cultural propagation of ludic agendas.

Finally, it was the market, that is to say a medley of agents large and small, who, embracing the ludic programme as commodity, promoted leisure in resorts, fairs and a host of establishments orchestrated around play and recreation. The consideration of leisure never again lost momentum as it became evident in the emergent ‘leisure industry’ and the ‘sport and leisure’ sections increasingly featured in newspapers and broadcasts.

A vast network of events surrounded the incorporation of the playground into the city. By 1972, Le Corbusier’s former assistant Georges Candilis was pleading for ‘Planning and design for leisure’, only that following a quantum leap, his concerns were then territorial, because leisure’s onslaught upon the landscape had become at that stage simply massive (Candilis, 1972).12

As observed by Cranz, early attempts at situating large sport arenas in cities were difficult: some of these were banished to liminal areas; others were grafted – not without resistance – on to parks (the institutions had gone public precisely when sport became recognized as an important mode of recreation). Others were squeezed into available sites. Suburbs became fertile ludic grounds as they expanded in tandem with increased sport demands (Cranz 1989). Fields were sometimes skilfully fitted atop buildings. These adaptive tactics came to characterize urban play facilities.

Thus, playgrounds became urban late-comers, for they were primarily grafted on cities, but their significant potential as incubators must also be acknowledged, for eventually whole districts also surged around play arenas. Thus, conceived as foundational elements, these usurped, so to speak, the function of squares, with the club house somewhat substituting the parish church. The transit from the grafted on to the foundational status of the urban field describes the ludic agenda’s urban success story.