HEALTH

Millennials are the wellness generation. We fill up yoga studios, CrossFit gyms, and SoulCycle classes, and guzzle coconut water and green juices. We download meditation apps and can expound on the purported benefits of rose quartz and Himalayan salt lamps. Millennial workplace team-building might be a group hike or a Tough Mudder. We believe time to exercise and eat well is a right; we want to prepare healthy meals with organic produce and hormone-free meat; we drink more water than soda; we know we should be eating more whole foods, mostly plants. We grew up with in-school antidrug curricula and then moved to cities that ban smoking in bars. We made seltzer great again. We are the generation of #selfcare and #MotivationMonday.

So why are we so unwell?

Millennial Madness

Maddie Campbell, the dog-walking Uber-driving Millennial living with her parents in Jacksonville, Florida, has one big thing working in her favor: she has health insurance because of the Obamacare mandate that young people can stay on their parents’ plans until they’re twenty-six. “I have a couple of different disabilities, I have PTSD, I have chronic illnesses,” Maddie says. Even so, if she wasn’t able to get insurance through her parents, “I really think I would be chillin’ without health insurance, and trying my best not to get sick.”

For a great many Millennials, “don’t get sick” is the plan. For others, it’s too late.

Millennial mental health is especially worrying. Older Millennials may be the most depressed thirtysomethings in American history. A Blue Cross Blue Shield analysis of health data found that we are significantly more likely to suffer from major depressive disorder than Gen Xers were when they were in their midthirties, and women are about twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with depression. That older Millennials may be more likely to be diagnosed with depression may mean that we’re more depressed, or it could mean that we are more willing to seek help for it—or some combination of the two. A portion of any population is simply biologically predisposed to depression. For another (overlapping) piece of the population, though, depression is also situational, sparked by stress and exacerbated by brain chemistry. For all the jokes about Millennials being triggered snowflakes, in truth we really are more aware of the importance of mental health: younger Millennials, a Harris poll on mental health and suicide found, were more likely than older adults to report having seen a mental health professional in the previous year, and almost twice as likely to say that seeking mental health care was a sign of strength.

So it’s particularly worrisome that we’re also less likely to be insured. While we might be more open to seeking mental health care, we’re a lot less able to afford it. One in five Millennials struggling with major depression, a condition that can shave nearly a decade off one’s life, goes without treatment. And 85 percent of people with depression are also struggling with at least one serious additional issue, whether substance abuse or chronic hypertension or Type 2 diabetes or a range of other afflictions.

Right now, Maddie’s insurance covers part of her therapy bill, so she only pays $35 per session. But $35 is a lot when your net worth is in the negative, and all of your disposable income is earmarked for paying down your debts. Maddie is happy with her therapist, but cost forces her to pass on other critical care. “My PTSD was initially so intense, I tried so many different things,” she says. “I tried TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and it worked pretty well, but it was super-expensive every session… It made me a lot better, but I couldn’t afford to go every week.”

We like to think we can separate out the psychological from the physical, but mental versus physical health care is a false dichotomy: mental health struggles have physical effects, and physical illness can hamper psychological well-being. Rates of suicide in America are soaring among Boomers and Millennials alike, and Boomers have the highest rates of any generation. Suicides in the US have long occurred among older people at higher rates than younger ones—when Boomers were coming of age, the suicide rate for people sixty-five and up hovered around 20 per 100,000—but rates are higher for the over-sixty-five cohort now than they were in the 1970s and 1980s. For Millennials, it’s not much better: suicide rates among eighteen- to thirty-five-year-olds shot up 35 percent between 2007 and 2017.

Millennials have also been hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis. Between 1999, when the oldest Millennials were turning nineteen, to when the youngest were becoming adults in 2017, drug-related deaths increased by 329 percent. Opioid-related deaths grew by 500 percent, and overdoses from synthetic opioids surged a ghastly 6,000 percent. Out of every 100,000 people between the ages of twenty and thirty-four, nearly 35 now die of a drug overdose every year.

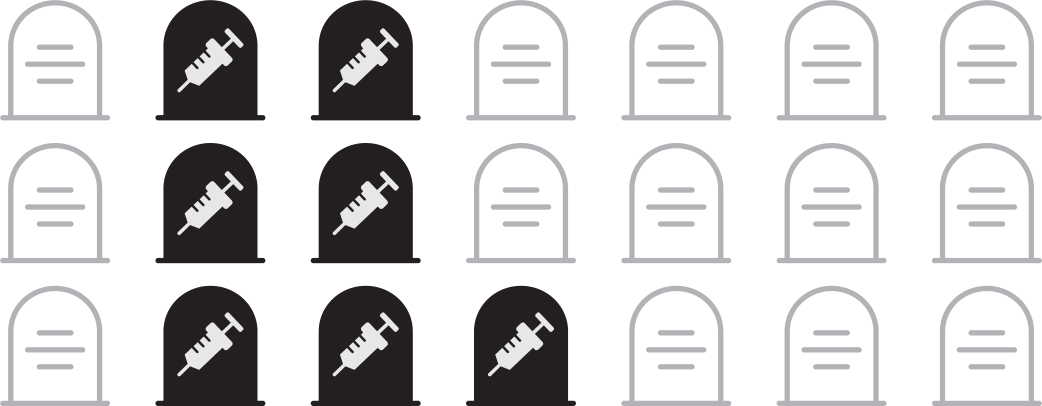

These deaths—drug overdoses, suicides—are what the economist Anne Case and the Nobel laureate Angus Deaton have called “deaths of despair,” and they are the primary reason the Millennial mortality rate is 20 percent higher than it was for Gen Xers at the same age. For white Millennials, a Stanford Center for Poverty and Inequality analysis of census data found, the mortality rate has shot up almost 30 percent. And these deaths stem from problems our health care system is particularly inept at addressing. An Ohio State University study found that people with drug-use disorders pay much more for care than those without. They were much more likely to wind up in an out-of-network hospital and to rely on out-of-network care, even compared to patients with congestive heart failure, an emergency condition. And those with substance addictions paid an annual $1,242 more for out-of-network health care than people with diabetes. Inpatient rehab programs run into the tens of thousands of dollars, and many insurance plans refuse coverage; even those that do may not cover a second (or third) stint in rehab, though rates of relapse are high for most addiction disorders. Drug rehab facilities also routinely turn away pregnant women.

Millennial mortality is up almost 20 percent compared to our Gen X predecessors. Out of every 100,000 people between the ages of 20 and 34, nearly 35 now die of a drug overdose every year.

So what’s driving Millennial depression, anxiety, and an uptick in death by suicide and overdose? Some researchers (and critics) have suggested that “helicopter parenting,” that hallmark of suburban Millennial childhood, left us unprepared to solve our own problems; that we were told we were special, and now we can’t handle the disappointment of realizing we’re not; that Mom and Dad had such a hand in navigating our conflicts, arranging our schedules, and even doing our homework that once we’re out in the world and expected to do those things on our own, we simply can’t handle it.

Maybe. Anecdotes certainly abound of parents calling their kids’ college professors to complain about a bad grade, or young people not knowing how to productively fight with a friend. Intensively parented kids very well may turn into anxious and less resilient adults. But when you look at the tangible challenges Millennials face, our allegedly overinvolved mothers seem like the least of our problems.

One of those problems is money: it may not buy you happiness, but financial stress ties closely with depression. As incomes rise, the incidence of depression goes down. When about a third of Millennial-headed households live below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL)—in other words, are poor or low-income—you can bet our mental health is going to suffer.

It can be difficult, and perhaps impossible, to untangle medical causes of mental illness from social ones. We know that for many people, pharmacological tools to treat chemical imbalances in the brain are profoundly useful and even lifesaving. But when you look at the vast landscape of challenges that so many Millennials face, in a world imbued with so much suffering, and where that suffering is more visible than ever, perhaps it is entirely rational to feel depressed and anxious. Perhaps these conditions reflect social problems as much as individual brain chemistry.

“Problems are now more often believed to be questions of personal brokenness than they used to be,” says Satya Doyle Byock, a Portland, Oregon, therapist who works primarily with Millennials. In the past, she says, human beings faced the same big existential questions we do today—who am I, why is the world what it is—but had a greater number of common and respected social outlets through which to examine those questions, whether it was religion or philosophy or prayer or contemplation. Now, there’s a sense that anxiety, depression, and malaise are issues of individual psychological dysfunctions to be individually fixed, not rational responses to irrational conditions worth collectively addressing. “Yes, there are sometimes medical solutions to mental health issues, and thank god,” Satya says. “But we are still human beings on a planet that is dealing with severe chaos, catastrophes, and suffering. Why would we not be trying to sort that through in our bodies and our souls?”

Millennials are, perhaps more than any other cohort, also suffering from a kind of generation-wide cognitive dissonance. There is a profound gap between the expectations we were raised to hold and the reality we now experience. Growing up, we believed that if we followed the rules and did the right things—go to school, get a job, be a decent and kind person—we would be rewarded and life would be, if not amazing, at least good, stable, and predictable. And, well, it wasn’t. A lot of us are entering our thirties underemployed, indebted, and living in our childhood bedrooms. That sucks, and we know it. “I deeply believe the things I learned as a child are true and important,” Dave Rini, a thirty-six-year-old Millennial in Boston, told me. “And then I see how they operate in the real world, and I don’t know how to deal with that.”

Millennials want to live lives of purpose, but we don’t have a road map for what that might look like. And as we struggle to piece together meaningful lives among the shards of a shattered economy, we are also bombarded with messages that we’re weak, sensitive snowflakes whose efforts at introspection are narcissistic and embarrassing. “We neglect the amount of trauma that Millennials have grown up with,” Satya says. “In almost every clickbait article and every discussion, there is a lack of acknowledgment of the rise of school shootings, the amount of imprisonment and incarceration, of immigration trauma, sexual abuse, rape, family abuse, family trauma, 9/11, growing up when your country is going to war for seemingly no reason. There are massive existential issues and personal traumas that Millennials are dealing with, and [they are] simultaneously being mocked for being so self-involved.”

When Millennials come to her office, Satya says, they are always quick to recognize their own privilege and to note how lucky they are and how, despite being in a therapist’s office, they don’t really have any right to complain. I had the same experience reporting this book: nearly all the Millennials I talked to, regardless of how severe their struggles, noted that they were privileged in some way; most were almost apologetic for suggesting that their pain might matter. “Millennials have been so mocked and ridiculed in culture that to actually want to look at one’s own suffering is immediately ridiculed by the mocking ingrained voice inside of everyone’s head,” Satya says. “We have been trained to make fun of our own introspection.”

And while the internet has increased awareness of mental health struggles, it’s also fueled them. “With Instagram, for example, the comparison of oneself to other people is extremely toxic,” Satya says. “Everyone says, ‘I don’t know why I’m the only one who doesn’t know what I’m doing.’ Everyone thinks they’re the only one who doesn’t have their shit together. Part of that is just standard blindness of self and others. But another part, of course, is that people put their best self up on the internet—or the new thing is that you put your most vulnerable self up, and so now it’s an authenticity competition. The resulting comparison is exceedingly toxic.” And conflict online is even worse than comparison. Anonymity, or even being behind a screen using our real names, can make us crueler than we might be with a person face-to-face, but our nervous system reacts to that feeling of attack all the same, even if it’s “just” coming from social media. “For younger people it’s even worse,” Satya says. “We at least have some impulse control. The younger you are, the shame, mockery, fitting in—it’s all so much more magnified with the internet.”

The Unwell-est Wellness Generation

Millennials’ physical health is in decline, too, and at a faster rate than our predecessors’. We are increasingly sedentary: in 2011, more than half of us sat for more than five hours a day, as compared to about a third of us in 2007. And we’re more isolated, spending significantly less time interacting with other human beings in person rather than through a screen. Less than a third of us talk to our neighbors, compared to 40 percent in 1995.

Older Millennials report higher rates of substance abuse, high blood pressure, Crohn’s disease and colitis, and higher cholesterol than Gen Xers did at the same age. By contrast, Baby Boomers are the longest-living generation in American history. Boomers who have made it to sixty-five still have about two decades ahead of them: men will live to be, on average, nearly eighty-six, and women nearly eighty-eight.

Comparing life expectancies is complicated work, because once a person lives past a certain age—in wealthy nations, fifty or sixty-five—they’re a lot more likely to keep living into old age. Given that a good chunk of the Millennial cohort is still under the age of thirty, and that we’re surrounding ourselves with the traditional trappings of adulthood later, it’s tough to look at our life expectancy compared to Boomers. What we do know is this: our health is trending in the wrong direction.

This is ironic, given the value Millennials place on our health. Compared to previous generations, we exercise more and eat healthier; we smoke less. And we have a more nuanced view of what it means to be “healthy.” While Boomers pretty much say that being healthy means “not falling ill” and not being overweight, Millennials are more likely to say that “healthy” is defined by eating well and exercising. And yet our health outcomes are still poor.

In 2011, more than half of us sat for more than five hours a day, as compared to just over a third of us in 2007.

Young people aged thirteen to thirty-five reportedly spend some $150 billion of their limited resources a year on nutrition, fitness, and health. As we have entered our twenties and thirties, Millennials have fueled an explosion of boutique fitness classes: the $25 yoga or barre class, $30 or more for SoulCycle and spinning, sometimes even more than that for personalized Pilates or boxing. We’re also partly responsible for the surge in organic, locally sourced, and sustainable produce, and we want it for our kids, too. (Who demanded the now ubiquitous gourmet organic baby foods? Millennials.) We’re more concerned about the environmental impact of how we eat, which is part of why we’re the force behind growing global veganism (between 2015 and 2018, the number of vegans in America increased by 600 percent). Even those of us who haven’t gone whole hog in forgoing animal products are pushing plant-based diets and the kind of “flexitarianism” that pops up in #MeatlessMonday campaigns and encourages reduced meat consumption.

Yes, there is a big class gap here. Flexing for Instagram from a chic boutique fitness studio in $140 Alo yoga pants is a particular way of signaling wealth; so is sipping a $12 Moon Juice, buying a $495 “intimate wellness solution” from Goop.com (it’s basically a very expensive vibrator), or going on a $1,395 Sakara cleanse before your wedding. But while the luxury market has embraced high-end wellness products, the push for health as Millennials define it has crossed class lines. Walmart sells organic produce. The YMCA and affordable gyms like Planet Fitness offer yoga classes. Local green thumbs have planted community gardens and health-conscious entrepreneurs have opened vegan cafés in neighborhoods long neglected by chain restaurants and big grocers. Even in the midst of coronavirus stay-at-home orders that shuttered gyms and exercise studios, public health messaging was clear: stand up, walk around, and get some exercise.

It’s easy to scoff at “wellness” as a trend at best and a Millennial money pit at worst. But I suspect there’s something else going on here. Millennials are facing a broken health care system with poor outcomes and high costs. And a system that assumes widespread employer-based insurance is badly underserving a generation of freelancers. As with so much else about Millennial life, the old systems have failed us. And so we’re trying to figure things out for ourselves.

Dead Broke

Maddie Campbell needs a filling. She can tell—her tooth hurts, and it’s not getting better. But her dental insurance doesn’t cover everything she needs done. “I can’t afford the filling I know I need,” she says. “So I’ll just chew with the other side of my mouth now.”

In 1970, health spending amounted to $355 per person. By 2018, that amount had increased thirty-one-fold: We now spend $11,172 per person on health care (even when adjusting to 2018 dollars, health spending has shot up more than 500 percent since 1970). Nationally, we spend more than $3.5 trillion on health care every year. Our out-of-pocket spending (that is, what we spend on health care not counting our insurance premiums) has also gone sharply up, from about $119 per person per year in 1970—$770, with inflation—to $1,150 per person in 2018. And when you add insurance, it gets worse: the average American household now drops nearly $5,000 per year per person on health care, including insurance premiums, prescription drugs, and medical supplies. In 1984, when Baby Boomers were giving birth to the babies who are now older Millennials, household health care spending was half of that.

For Millennials having children, the numbers are no better. The cost of having a baby has tripled since 1996: A vaginal delivery will run you $30,000, while a C-section is more than $50,000. If you have employer-sponsored health insurance, lucky you, but you’ll still be on the hook for an average of $4,500 in out-of-pocket costs. That is close to the total cost of having a baby in Switzerland or France, which is largely covered by the state. Women in those countries pay virtually nothing for their deliveries. That used to be true in the US, too: as recently as the early 1990s, Elisabeth Rosenthal reported for the New York Times, American women’s out-of-pocket childbirth expenses were close to zero—unless they opted for special extras, like a private room with a TV.

Nor do these extortionate sums translate into better outcomes for mothers and babies. The US maternal mortality rate has more than doubled since the years in which Millennials were being born. Two-thirds of US maternal deaths are preventable, and African American women are especially vulnerable: they are two and a half times as likely as white women to die bringing new life into the world. Black babies, regardless of their mother’s income level or educational attainment, are also far more likely than white babies to die before their first birthday. The baby of a poor white mother without a high school diploma is more likely to survive than the baby of a black woman with a graduate degree. Millennial women, and black Millennial women in particular, are dying from a health care system that is not only woefully inadequate but deadly racist.

Racial disparities in health care and health outcomes are significant. There is, first, just straight-up racism: white health care providers are less likely to recognize black patients’ pain, and one study by University of Virginia researchers found that a shocking 40 percent of white first-year medical students, and a quarter of white medical residents, believed that black people’s skin was thicker than white people’s. And then there are the many outcomes of centuries-long racism that are slow-drip factors leaving many people of color in poorer health and more vulnerable to disease. Communities of color are more likely to live near polluted areas, where they’re breathing in carcinogens, and less likely to have easily accessible local grocery stores where they can get fresh fruits and vegetables—all of which contributes to higher rates of disease, including asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Redlining meant systematic underinvestment in what are now often low-income neighborhoods, which in turn means fewer high-quality health care providers. Discrimination in home buying means that African Americans, who are less likely to own their homes, are more vulnerable to housing instability and evictions, which we know fuels ill health. Our absolutely asinine system of tying health insurance to employment means that the same communities facing disproportionate rates of unemployment or underemployment because of discrimination, incarceration, poverty, and ill-health are also less likely to have private insurance coverage. “Black people are poorer, more likely to be underemployed, condemned to substandard housing, and given inferior health care because of their race,” Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor wrote in The New Yorker in 2020. “These factors explain why African-Americans are sixty per cent more likely to have been diagnosed with diabetes than white Americans, and why black women are sixty per cent more likely to have high blood pressure than white women.”

We saw this all come home to roost with the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit communities of color, and African American communities in particular, extremely hard. “The old African-American aphorism ‘When white America catches a cold, black America gets pneumonia’ has a new, morbid twist,” Yamahtta-Taylor wrote. “When white America catches the novel coronavirus, black Americans die.”

During the coronavirus epidemic, long-overlooked employees who stock drugstore shelves, take vital signs, ring up grocery purchases, and make deliveries found themselves thrust to the front lines of the outbreak and deemed “essential.” A New York Times analysis found that a majority of these “essential critical infrastructure workers” were women. Three-quarters of the health workers infected with COVID-19 as of April 2020 were women. The Times didn’t offer a racial breakdown, but many of the jobs deemed most essential—nurses and health aides, grocery and fast-food counter workers—are disproportionately filled by women of color. African Americans are about 13 percent of the US population but make up 30 percent of health aids and nursing assistants. Of that 30 percent, 88 percent are female.

Millennials, too, were likely to be on the front lines, because we are disproportionately employed by the kinds of businesses that didn’t close. We’re 49 percent of restaurant and food service workers, 46 percent of pharmacy and drugstore workers, 46 percent of warehouse and storage workers, and 45 percent of gas station workers. And the black Millennials who are more likely than their white peers to work in the gig economy? Many of them spent the shelter-at-home periods working for the various services that send a shopper out to get your groceries and drop them at your door—often without the most basic safety supplies, let alone health insurance.

No wonder so many Millennials say our health care system doesn’t work.

We are the least likely adults to be insured. Almost half of young Americans don’t have a primary health care provider; around 15 percent of Boomers say the same. And despite the fact that our health care spending is lower overall, we are the group most likely to have medical debt, even though we are more likely than Boomers to know the cost of our care before we receive it. But that’s a double-edged sword: we’re also twice as likely as Boomers to forgo care we need to avoid the bill.

We may also opt for substandard care to fill the gaps. That’s what Maddie is doing now. She has polycystic ovary syndrome, which can cause hormonal imbalances, heavy bleeding and irregular periods, and endometriosis, a chronic and painful condition where uterine lining grows outside of the uterus. One treatment for both is hormonal contraceptive pills, which Maddie’s doctor tells her to take continuously, and so she gets her prescription filled in three-month supplies. The brand that causes the fewest side effects costs $150 per month. That means she’s regularly dropping $450 she really can’t afford on medication, often putting the cost on a (now maxed-out) credit card. “I just went to the doctor yesterday and he’s going to try to put me on a cheaper birth control that may give me horrible mood swings,” Maddie says. “But if it’s nine dollars, I’d rather pay that and feel shitty and have my symptoms mostly managed than feel great and have to spend so much money every month.”

These are the choices Millennials are forced to make in one of the most prosperous nations in the history of the world.

There is no singular cause of our swelling health costs and worsening outcomes (especially for women giving birth), but a look at the component parts of this mess is revealing: the architects, and the beneficiaries, are mostly Boomers.

To put it succinctly: 1980, the first year Millennials were sliding into the world, was a tipping point. According to Austin Frakt, the director of the Partnered Evidence-Based Policy Resource Center at the V.A. Boston Healthcare System, associate professor with Boston University’s School of Public Health, and a senior research scientist with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (lots of titles for this guy), the US was humming alongside our economic peers until we peeled off—for the worse—in 1980, when our health spending began to radically outpace that of other nations. In the years that followed Ronald Reagan’s election to the presidency, Frakt wrote for the New York Times, deregulation allowed the market to control medical costs, which meant that they ran wild. (Other developed countries kept costs down with price controls, and expanded national health systems.) The American insurance system comes with a massive administrative sector—people whose job it is to deny or accept claims, manage billing, and negotiate between insurers and providers—all of which drives up costs that are passed on to the patient. And of course, insurance companies are in the business of making money. Who do you think they’re making it from?

American families spend more than twice as much on health care today as they spent in 1984, when Boomers were young heads of households.

Even though health spending was up, health outcomes were not. Nineteen eighty, Frakt writes, was again a major turning point. While our economic peer nations have seen their populations get healthier and healthier over time, and while their life expectancies have steadily increased, Americans didn’t keep pace. Why? Because America simply does less for its people, and especially for its poor. A series of Boomer and Boomer-elected presidents have further slashed holes in the American safety net and in welfare benefits for the vulnerable; as a result, Americans die younger and more often than people in economically similar countries.

Bill Clinton tried at least to patch up some of the more obvious holes. His wife, Hillary Rodham Clinton, took charge of reforming what he called “a health care system that is badly broken.” Republicans and those who profited from the existing health care system immediately opposed the effort, despite the fact that the reform plan was moderate and market-friendly; it didn’t help that the plan was complicated, and communication to the public poor. As soon as the plan was announced, conservative media outlets, organizations, and politicians launched a broad attack aimed at convincing Americans that it would be a radical government expansion that would make their health care worse. When Republicans triumphed at the ballot box in the 1994 midterms, Clinton-era health care reform was dead in the water.

Clinton and others did succeed in establishing, in 1997, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP, today CHIP), which covered children of families who made too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to afford insurance themselves. The number of uninsured children fell to its lowest in American history up until that point, and long-standing racial disparities in health coverage began to shrink. Today, more than half of black and Hispanic children, and more than a quarter of white children, are insured through CHIP. A whole lot of Millennials had health care as children because of CHIP, and today, a lot of Millennials’ own children can go to the doctor because of it.

But once young people aged out of CHIP—at nineteen—we were up a creek. From 2003 to 2010, the number of uninsured young people rose; by 2010, 29 percent of Millennials—20 million of us—didn’t have health insurance. Because companies cut benefits, and because of the Great Recession, eighteen- to thirty-four-year-olds (mostly Millennials) made up nearly half of the uninsured workforce in 2010, even though that same group was only 36 percent of workers.

We caught a bit of a break when Barack Obama pushed through the most significant change to the American health care system in Millennials’ lifetimes. The Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) is far from perfect, and nowhere near the universal systems enjoyed in many of our peer nations. Health care and insurance both remain ludicrously expensive, and a great many Americans are still one health catastrophe away from bankruptcy. But it filled some of the more egregious gaps, especially for Millennials. In the first three years of Obamacare alone, 2.3 million young adults either stayed insured or became insured through a parent’s plan. Basic preventive care, including contraception, was mostly free. Insurers could no longer discriminate based on preexisting conditions, which a Department of Health and Human Services analysis found could have denied insurance to as many as 46 percent of twenty-five- to thirty-four-year-olds. The many of us who freelance or work in the gig economy had more options. Some 8.7 million women gained maternity coverage. Because of Obamacare, the number of uninsured Millennials halved. If conservative states had taken the option to expand Medicaid, the number of uninsured Millennials would have decreased further still.

And then came Donald Trump.

The Trump administration, and the Republican Party more broadly, have gone out of their way to gut Obamacare. Unable to repeal the act wholesale, Trump instead destroyed whatever he could. He cut the advertising budget, so fewer people knew how and when to sign up each year, and he shortened the amount of time Americans had to complete those sign-ups. Trump also cut funding for the trained navigators who helped consumers and businesses understand their options, eligibility, and the enrollment process. Predictably, enrollment dropped, and lots of people who needed and wanted health care coverage didn’t get it. Trump also ditched the individual mandate, a critical component of Obamacare that brought down insurance premiums by forcing younger and healthier (less costly) people to get insured. He made it harder for poor people to get Medicaid, and easier for states to kick poor people off. He cut federal payments that incentivized insurance companies to remain on the Obamacare marketplace. And he let more people stay on crappy, skimpy plans that are intended to be short-term precisely because they have enormous deductibles, meaning you could have insurance and still go bankrupt if catastrophe hit.

When catastrophe did hit, in the form of a pandemic, Trump didn’t stop his efforts to undermine Obamacare’s gains. Democrats and health insurance companies alike pushed the president to reopen the Obamacare enrollment window—after all, the numbers of sick people were growing, and the CDC’s worst-case predictions in March 2020 had 214 million people sick and as many as 1.7 million dying. Unemployment was exploding in a nation where health coverage is tied to employment, leaving tens of millions of people newly uninsured in a world convulsed by a highly contagious and often deadly disease. Still, Trump refused to reopen Obamacare enrollment, which would have allowed people without insurance to get it and people with substandard insurance to level up. All the while, Republicans had a lawsuit pending before the Supreme Court aimed at dismantling Obamacare without offering a replacement; Trump was a public supporter, although his administration offered no real plan of its own, even in the midst of a massive deadly outbreak. The individual financial reverberations, including personal bankruptcies, will be felt for years to come.

To no one’s surprise, health care premiums have gone way up under Trump. Nearly 70 percent of Americans say they worry about being able to afford unexpected medical bills. Some Millennials are staying in jobs they hate because they can’t afford to lose their insurance; others are quitting jobs they love because adequate insurance isn’t on offer. And many employers increasingly treat health insurance as a perk rather than a requirement. Between 1989 and 2011, the percentage of recent college graduates who got health insurance through their jobs was cut in half. And the insurance we do have is worse: 82 percent of employer-sponsored plans now have deductibles, compared to 63 percent ten years ago, and average deductibles have gone up from $826 to $1,655.

No wonder so many Millennials want what our Boomer parents have: Medicare. Or at least something like it. Or at least something.

A majority of Americans now say they want a universal health care system, and Millennials are leading the way. A Morning Consult/Politico poll found that 70 percent of us support a universal health care plan where health coverage comes via the government. Early in the 2020 Democratic primary, a Hill-HarrisX survey found that about 60 percent of Millennial Democratic voters said they would be more likely to support a candidate who backed a Medicare for All plan. While voters on Super Tuesday broke for Joe Biden over Bernie Sanders, there was a glaring age gap: 58 percent of voters under thirty, and 41 percent of voters under forty-five, cast their ballots for Sanders. Health care was at the top of a lot of voters’ minds, and those who put health care as their number-one issue were more likely to vote for Biden. But voters who said that they wanted a single-payer system as opposed to our current private employer-based one broke for Bernie by a significant margin.

Not every Millennial wants a Sanders-style Medicare for All plan. But we largely do want better health coverage, and as a generation of freelancers, contract workers, and part-timers who have lost jobs again and again, we’ve seen firsthand the absurdity of tying health insurance to employment. You would think this would be common ground (and perhaps, in the aftermath of coronavirus, massive layoffs, and widespread illness, it will be). After all, older Americans love Medicare, their universal health care program. Three-quarters of Medicare enrollees said they were satisfied or very satisfied with the program in a 2019 consumer survey. They oppose any cuts or even changes to the program, and overwhelmingly say that it’s important to them and their families. All of which is great: Medicare is wonderful, and even though caring for aging Boomers on the government dime is really, really expensive, we prioritize it and we can afford it. Millennials agree that keeping it funded and functional is the right thing to do. We don’t want to take Medicare away from our parents and our grandparents.

We just want in. Boomers, unfortunately, don’t seem interested in sharing. Consider this a plea: We don’t want to take your health care, and we know that you’re struggling with our broken health care system, too. We want you to have affordable prescriptions. We want you to go to the doctor when you’re sick. Boomers, you’re our parents and grandparents, bosses and mentors, friends and neighbors. We love you, we really do. We want you to be healthy and live for a long time.

Do you want the same for us?