You know everything you need to know to put 3Sig to work in your accounts right now. You might still hesitate, though. It’s nothing like the advice you’ve read and heard elsewhere. You know it’s a simple plan and understand each part of it, but may not be able to picture it in action through the chaos of the market.

To get around this, we’ll watch how an investor uses the plan over a time period fraught with real news, and how the plan compares with more typical long-term investment approaches. We’ll do so by following the lives of three fictional investors at the same company, on the same earnings path, using the same 401(k), and dealing with the same maelstrom of events ripped from the headlines. The only difference among the three is what they do with their same level of savings within the same set of investment options—with wildly different results. Two of the characters are archetypes of the most common investment personalities I’ve encountered: the part-time trader plagued by z-vals and the diligent saver unnerved by volatility. The third runs 3Sig.

I want you to feel clearly the power of 3Sig, to see how it makes investment life easier and more profitable, so we’re going to go into some depth. Sit back with me as we navigate actual news stories and z-val forecasts to understand the impact they have on people trying to plan for the future while living life. Notice how forecasters have always seemed believable, and how they’ve always said many of the same things you hear them saying today. Notice, too, that they’ve been wrong about half the time. File this away in your wisdom vault. Investing wouldn’t be a challenge if the experts looked like buffoons. It’s a challenge because they look like experts and we want to trust them, but they’re wrong as often as amateurs.

This chapter will give you more than a textbook view of 3Sig. It will take you into the real-life experience of running the plan so you know what to expect when implementing it in your own life.

The Setup

Our three investors begin at age thirty as new employees at SnapSheet, an information analytics company based in Denver, Colorado. Each is a data scientist with a different specialty. Their family situations are different, too. Garrett is married without children, Selma is a single mother of two, and Mark is married with three children. Each started his or her career at SnapSheet with an annual salary of $54,000 at the end of 2000. That was $4,500 per month, from which each contributed 6 percent, or $270, to SnapSheet’s 401(k). The company matched 50 percent of contributions up to 6 percent, which is why all three contributed the minimum amount to get the maximum company match, pushing their net monthly contribution up to $405, or $1,215 per quarter. From their retirement accounts at previous employers, each transferred $10,000 into SnapSheet’s 401(k). So their initial investment balances were $10,000, and their starting quarterly contributions were $1,215.

Garrett had always been interested in the stock market. In his twenties, he read trading books, attended a technical analysis seminar, and opened an individual brokerage account where he’d tried his hand at picking a few winners. His results were mixed, but he felt he’d been improving at the time he hired on with SnapSheet and took a look at its 401(k). He was happy to find that it offered a long list of mutual funds and also included a brokerage option where he could buy and sell anything he wanted. He was eager to do so, especially since he believed cheaper prices after the dot-com crash provided potential to get ahead in a recovery.

Selma’s main concern was taking care of her two children on a single salary. The last thing she wanted to worry about was the whim of Wall Street, so she’d read financial planning books and taken a community college class on asset allocation for the long haul. She was happy to find a suitable collection of mainstream mutual funds in the SnapSheet 401(k). With them, she would create a retirement mix that benefited from the long-term growth of the stock market with some safety added by putting some of her account in steadier funds. She got to work choosing the right mix.

Mark was a dedicated family man, leaving work at work and spending as much time as possible with his wife and three kids. He shared Selma’s desire to keep the whim of Wall Street out of his life, but he knew he needed the growth potential of stocks in his retirement account. He researched asset allocation as a way to balance growth with safety. The problem he noticed was that doing so didn’t produce as much profit as he was hoping to amass. He studied stock index funds as a low-cost way to get more performance with more risk that paid off in eventual recoveries from setbacks, and then stumbled onto 3Sig. He liked it best of all because it would focus his capital not just on stocks, but on the highest potential small-cap segment of stocks, supported by the bond account for stability and quarterly trades based on the signal. It would also provide him with buying power in a downturn, something his past experience with dollar-cost averaging never had. The 3Sig technique seemed like the best way to get high profits with little stress out of low-cost index funds, so Mark decided to adopt the plan.

When these three began work at SnapSheet in early December 2000, the Nasdaq had fallen 45 percent since peaking on March 10. The presidential election had been a fiasco, and when the three arrived at SnapSheet, the country still didn’t know whether George W. Bush or Al Gore had won. On December 12, the Supreme Court would decide that Bush was president, but after that it would be discovered that Gore had actually won the popular vote. The crashing Nasdaq and contentious election made it a tough time to decide where to invest a 401(k).

Garrett thought the deflated Internet stock universe, which was taking a pounding almost daily in the media, offered a lot of latent value. He looked back at the darlings of the bubble—JDS Uniphase, Nortel, Sycamore, and others—and thought he finally had a chance to buy on the cheap all the stocks those bragging blowhards at his former company had teased him about for not owning in the final three years of the 1990s. What he called bragging blowhards you and I know as Peter Perfect. Garrett was vulnerable to their taunting.

He figured it would be hard to pick through the rubble of the Internet wasteland, but worth it, and he knew just the man for the job: Ryan Jacob, of Jacob Internet Fund fame. Sure, Jacob was being keelhauled by every reporter as the best fish-in-a-barrel proxy for what went wrong with net stocks, but Garrett had a feeling Jacob would be the star of “Comeback Kid” cover stories within a few years. About the time the latecomers piled in for the next phase of online stock growth after such stories, Garrett figured he’d be up 100, maybe 300 percent. That’s what happened in the good old days of just a year or two earlier, and so he thought it would happen again, and with a vengeance now that Jacob’s Internet Fund was beaten flat on its back.

Landon Thomas Jr. wrote in the New York Observer in October that Ryan Jacob used to be famous as an Internet investing rock star after turning $200,000 into $25 million in 1998, taking the top performance spot among mutual funds that year. Currently, however, his fund ranked dead last after losing 54.1 percent year-to-date. “Yet Mr. Jacob remains nothing if not steadfast,” Thomas wrote, citing Jacob’s praise of his third-largest holding, a company called iVillage, which topped out at $100 per share in April 1999 but was now $3. Jacob told Thomas, “The stock has underperformed, not the company.”

Garrett decided it was time to really go for it, and so he put half his $10,000 into Jacob Internet Fund for the recovery. The other half he decided to put into more traditional stock funds, just in case the Internet didn’t have as much recovery potential as he suspected.

He chose Wasatch Small-Cap Growth after it topped a list of “Small-Cap Growth Funds with Long-Tenured Managers” at TheStreet.com, which said the fund “has a record that’s tough to ignore. Jeff Cardon has held the reins since the fund’s 1986 inception and his track record is solid. Thanks to his measured approach, the fund beats 75 percent of its peers over the last one-, three-, five- and 10-year periods, according to Morningstar.”

Garrett selected Janus Global Technology for a wider perspective on tech potential than Ryan Jacob specialized in. He read the following in “Mike Molinski’s FundWatch” at MarketWatch in October:

A recent study by fund-tracking firm Wiesenberger found that global technology funds actually have a lower standard deviation than domestic technology funds, 47.65 versus 61.62, meaning that day-to-day, their closing prices don’t stray as much from their average price. . . .

What’s more, adding a global technology fund to an all-domestic portfolio can reduce the overall risk level of your investment portfolio because foreign stocks don’t move in tandem with U.S. stocks, thus reducing your exposure to a big drop in the U.S. market. . . .

The largest global sector fund is Janus Global Technology, which raised a staggering $10 billion in its first year in 1999 and returned 211.55 percent. This year, the fund isn’t doing so hot, down 0.68 percent as of Sept. 30.

Right, Garrett thought, but it’s exactly the “isn’t doing so hot” part that leaves tech funds at amazing bargain prices for the few people smart enough to understand what the word recovery means. Since the Nasdaq peak on March 10 through the end of November, Jacob Internet was down 81 percent, Wasatch Small-Cap Growth was down 4 percent, and Janus Global Tech was down 51 percent.

Garrett would begin 2001 with his $10,000 allocated thusly: $5,000 in Jacob Internet, $2,500 in Wasatch Small-Cap, and $2,500 in Janus Global Tech. He also specified that each of his $405 monthly contributions be divided by the same percentages. He’d keep the plan going this way for the time being, while he got his bearings at SnapSheet. Once he was comfortable on the job and had more time for stock research, he’d add some of his own picks to the mix for even better performance.

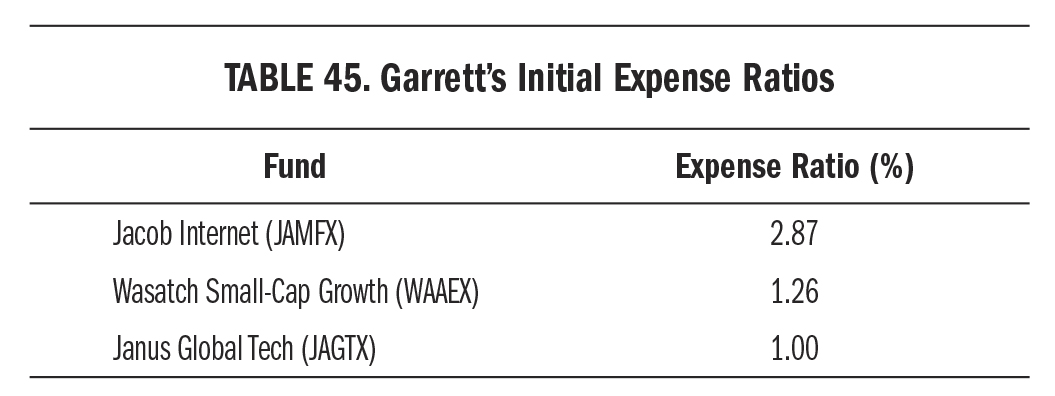

While Garrett was understandably bewitched by the compressed-spring appearance of these three funds, their veneer of potential performance was less impressive when peeled away from the guaranteed cost of their underlying expenses. Garrett would certainly pay up for potential performance:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1CmAAA9) for a larger version of this table.

Well, who knows, maybe he’d get performance so huge it would swamp expense concerns entirely. That’s what the z-vals selling expensive funds always promise. Garrett went into 2001 betting they’d be proven right by the recovery dead ahead, and he’d be made richer.

Selma took a different approach. She’d become very cautious with her meager savings after the dot-com meltdown cost her her job and a big piece of her retirement account. In a fresh start, she wanted to minimize danger to her savings. After she landed the new job at SnapSheet, she met with a financial planner at her church and told her she wasn’t sure she wanted to own any stock funds in her retirement account. Not one. “Not owning stocks in your retirement account is like not planting flowers in your flower bed,” the planner told Selma. “Flower beds are for flowers, not just ground cover. Retirement accounts are for stocks, not just bonds. If you put nothing but bonds in your retirement account, it’ll be as dull as a flower bed without flowers.” Selma thought dull sounded pretty good compared with the fireworks since March, but she got the planner’s point.

The planner took Selma through a series of questions to determine her risk tolerance, even though Selma quipped, “Let me save you some time: low.” After the questions confirmed Selma’s prediction, the planner overruled the result and suggested that Selma put 80 percent of her retirement capital in stocks. Selma felt queasy about this. She had a lot of working years in front of her, though, and the planner said that, in the long run, stocks always recover, so Selma took a deep breath and grudgingly agreed to put 80 percent of her retirement in stocks.

As was her way, she carefully researched at the library over several weekends. She printed out fund ratings from Morningstar for each of SnapSheet’s 401(k) offerings that appealed to her. She read articles and a seemingly endless collection of fund rankings. “Funds That Go up When the Market Goes Down,” “Three Top-Rated Growth Funds for the Long Haul,” “The Best Low-Volatility Funds for Gun-Shy Investors,” and similar fare usually featured a few comments by the managers of the winning survey, photos of them in the office, and then a wrap-up along the lines of the manager having “stood the test of time” or being a “veteran of the markets” or “battle-hardened,” unless the manager was new, in which case he or she “showed promise” and would probably “breathe new life into performance.” It was overwhelming at first, but Selma was no dummy and quickly detected repeating patterns and began grouping her options in a way that made them easier to rank and assemble.

She wanted to put the bulk of her capital in large-cap U.S. stocks, which she came to see as the most basic way to gain exposure to the stock market. She wasn’t interested in specializations or any type of focus, just the reliable blue chips that comprise the backbone of the market. Among such funds in the SnapSheet plan, she settled on Fidelity Growth & Income and Longleaf Partners as the best choices.

Fidelity Growth & Income garnered rave reviews at the end of 2000 for having wisely limited its exposure to overvalued tech stocks. Manager Steve Kaye positioned the portfolio defensively going into the tech wreck, owning bargain-priced health care companies and steadily growing financial stocks instead. Morningstar analyst Scott Cooley concluded in November 2000 that Kaye’s “low-turnover, cautious approach has served shareholders well for the long haul. During his nearly eight-year tenure, the fund has roughly matched the S&P 500’s return while exhibiting less risk than the index. In short, this still looks like a solid core holding for conservative investors.” That sounded perfect to Selma, who was certainly conservative. She would put a quarter of her retirement in Fidelity Growth & Income.

Similarly conservative, the manager of Longleaf Partners, Mason Hawkins, came off as a wise grandfather figure who would steer Selma’s account higher through whatever happened next. He had incentive to do so because he and others on the team were required to keep all their invested assets in the firm’s funds. Selma liked this. Longleaf Partners actually gained money in the second quarter of the year, when almost everything else had been crashing from the Nasdaq peak in March, and Hawkins told The New York Times in July, “We have not changed the way we do things for the 26 years that we’ve operated.” His fund was highly rated, and he was highly respected, and seemed about as far away from the flash-in-the-pan Internet madness as one could hope to get. Morningstar analyst Christopher Traulsen wrote in August that what the fund did best was “scour the market’s unloved for diamonds in the rough, buy them cheap, then hold tight until everybody else catches on.” From the Nasdaq peak to the end of November, Longleaf Partners rose 34 percent. No doubt about it, Hawkins was her man. Selma would put a quarter of her retirement in Longleaf Partners.

As for the other 30 percent of Selma’s allocation to stocks, the planner recommended international funds. “They can zig when the U.S. zags,” she explained. Among international stock funds in SnapSheet’s 401(k), two caught Selma’s attention: Artisan International and T. Rowe Price International Stock Fund.

Mark Yockey had been in charge of Artisan International since 1995. Media offered nothing but praise for his stewardship. He told interviewers about his belief in fundamental value and how his team looked for companies that could grow for decades. They hunted long-term trends and then found companies sporting the best business models to benefit from them. The cheapest among those comprised the sweet spot of the global market, the stocks Artisan wanted to own.

Morningstar analyst Hap Bryant wrote at the end of March that the fund “finished 1999 in the foreign-stock category’s top quintile, thanks to big stakes in technology and telecommunications stocks,” and he credited Yockey’s growth strategy for this. In October, analyst William Samuel Rocco added, “This fund continues to handle whatever the world’s markets throw its way.” He noted that it “encountered anything but favorable conditions in 2000” and that “Yockey slashed the fund’s telecom exposure in March” and “found opportunities in the media and financial sectors.” Rocco continued:

Thanks to these moves, the fund, unlike many of its growth-oriented peers, hasn’t relinquished the big lead it established early in the year (when telecom and tech stocks flourished). Despite posting a loss, it’s ahead of 75 percent of its rivals for the year to date through October 23, 2000. The fund has outpaced even more of its rivals over the long term by placing in its group’s top decile three times in the past four calendar years.

This was all very encouraging, but the part that really cemented Artisan International into Selma’s portfolio was an aside near the end of Rocco’s report, that “the fund has suffered only average volatility along the way” and that its expense ratio was declining. She’d put 15 percent into it.

The other 15 percent of her foreign stock allocation would go into T. Rowe Price International Stock Fund. Rocco wrote in November that it had “been an incredibly steady performer in the past,” faring well in “the sell-offs of 1990 and 1994 as well as the robust rallies of 1998 and 1999” such that it had “outgained its average peer by about one percentage point per year during the past decade.” Best of all, as far as Selma was concerned, Rocco considered the fund to be “a solid option for those who are seeking a conservative foreign-stock holding.”

Her remaining 20 percent she would put into bonds, half of it in Oppenheimer Global Strategic Income Fund and half in PIMCO Total Return.

Morningstar’s William Harding reported in October that the Oppenheimer fund’s “eclectic mix of bonds has produced good results so far in 2000.” It was the fund’s safety that appealed to Selma, with its eight hundred issues “limiting the impact of individual disasters.” Harding wrote that its five-year returns landed it in the top third, “while its volatility has been below the group’s norm. Seasoned management and a hefty yield are two more reasons to consider this offering.” Selma would more than consider it; she would put 10 percent of her account into it.

Like Hawkins at Longleaf, Bill Gross at PIMCO Total Return was a legend in the business. Sarah Bush at Morningstar wrote in March, “When manager Bill Gross acts, the investment community tends to take notice.” He’d loaded up on long-term Treasuries ahead of a buyback, which he said would shrink supply and drive up the prices of the bonds he bought, and that’s exactly what happened. His success over the years had been driven by identifying and exploiting such anomalies. Bush wrote that “despite the occasional misstep, this fund has consistently outperformed both its index, the Lehman Brothers Aggregate and its intermediate-term bond peers. With a 10-year return that ranks among its group’s best, it’s no surprise that when Gross talks, the bond market listens.” From the Nasdaq peak to the end of November, PIMCO Total Return rose 9 percent while paying a dividend of about a nickel per share every month, for a total of $0.48 paid over nine months. Selma would put 10 percent of her retirement under the guidance of Bill Gross.

Selma liked the bond market’s steadying influence on a portfolio, especially in conjunction with her fairly safe stock fund choices. Surely, she thought, with a quarter of her money run by the legendary Mason Hawkins and 10 percent of it run by the legendary Bill Gross, she’d be fine. That was more than a third of her retirement allocated to legends in the business, and two-thirds allocated to other well-respected managers known for above-average returns from only average or below-average volatility.

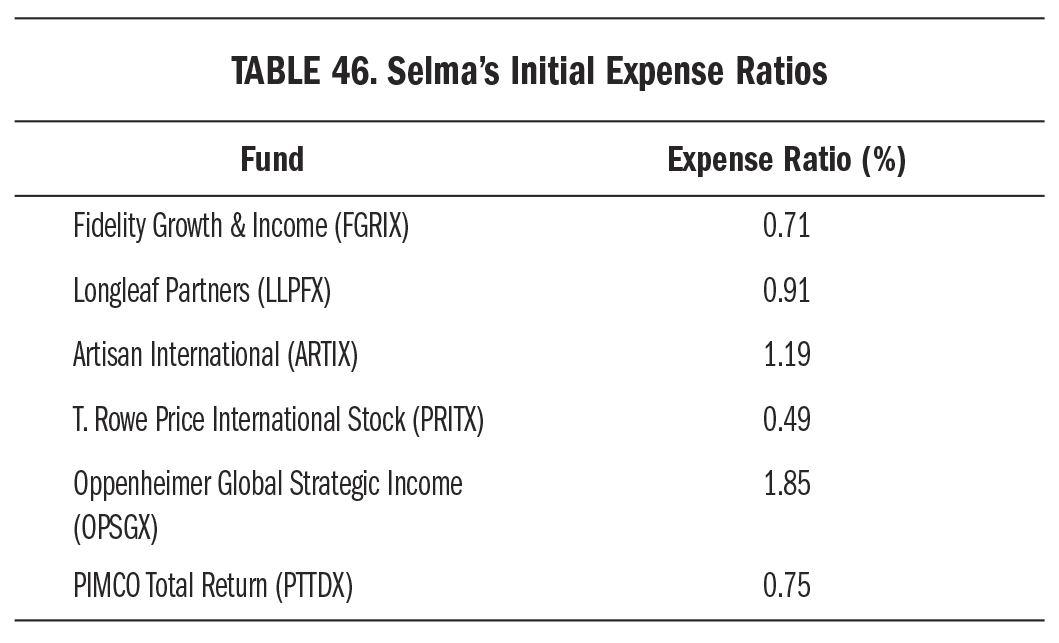

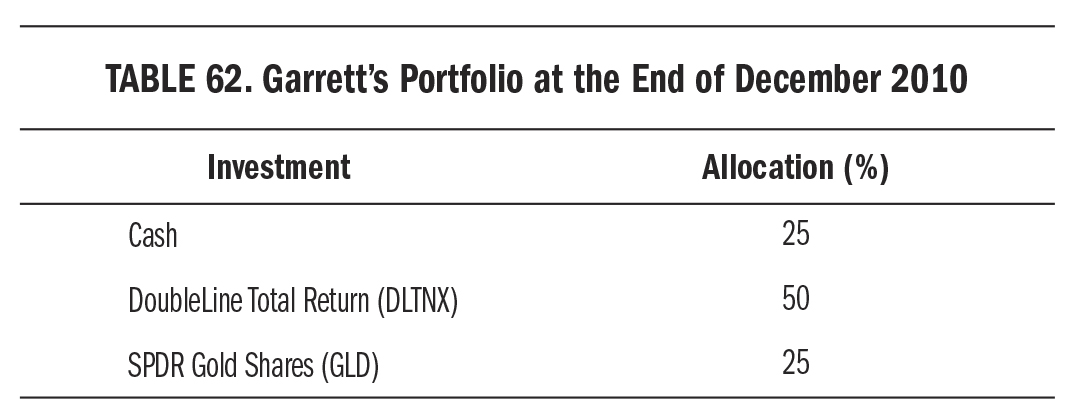

Selma did a good job. Her portfolio was sensible. Her $405 per month would be divided among the six funds in the same allocation as her initial mixture, for steady, reliable growth. She knew the dollar-cost averaging would help her take advantage of price swings without needing to worry about eventual recovery. Her top-notch managers would see to that. One thing she didn’t pay close attention to was the cost of her portfolio, which is easy to overlook among glowing reports on legendary and well-respected managers. Here’s what she paid:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1CvkzYY) for a larger version of this table.

This is better than what Garrett faced in the expense department, but still far above the tiny fees associated with index funds. Also, the Oppenheimer fund included a deferred sales load that Selma would have to pay if she sold shares within six years, but she ignored it because she knew the account was for the long haul and because the financial adviser had said Oppenheimer was well known in the business and quite popular. Selma figured that if anybody could earn the higher charges, it was the six first-rate management teams she’d selected. The final solidifying input from the financial planner was that Selma’s allocations to domestic stocks, international stocks, and bonds was correct for her age, and the diversification into two funds for each asset class provided further safety. “There’s no optimum number of funds,” the planner said, “but your six look very good for your temperament and time horizon.” Great! Selma was set.

Mark’s plan was the easiest to start. He’d concluded in the years before joining SnapSheet that active management wasn’t for him, regardless of rave reviews and glowing reputations. After he discovered the low-cost advantage of index investing and the fact that it beats almost all active managers, he set about finding the best way to grow an index fund portfolio. The only two approaches that appealed to him were dollar-cost averaging and 3Sig. He’d gone with dollar-cost averaging in a diverse mix of stock index funds at his former employer. The portfolio grew like clockwork in the late 1990s, but then he entered the dot-com crash fully invested and unable to do anything but watch his portfolio melt away. Had he sold at the peak a year earlier, the end of 1999 or even sometime in early 2000, he’d have been fine. When prices began retreating, though, he knew it was the time to keep going with his monthly purchases, so he did. The problem was, they were so small in comparison to the thousands disappearing monthly from his account. He found himself wishing he’d had some real buying power into the depths of the crash, and that’s when he remembered 3Sig.

He’d sold all his stock funds and hid out in cash during his unemployed months before SnapSheet, worried for his wife and three children the same way Selma worried about her two children. While job-hunting, he consolidated everything he had in the safest place possible. Once he was hired at SnapSheet, he turned his attention to the new 401(k) at his disposal and again faced the trade-offs between dollar-cost averaging and 3Sig. “What really went wrong?” he asked his wife at the dinner table one night in their new home, after the kids had been excused.

“The market crashed,” she replied.

“I know, but if that’s what markets do now and then, and if it craters my retirement account every time, then I’m doing something wrong.” She offered that maybe they should own safer investments. “That could work,” he agreed, “but then we end up underperforming most of the time, when the market rises.” He reminded her of 3Sig, how it would keep them mostly invested in high-performing small caps, but with a 20 percent bond buffer to be able to “really wade in when the market collapses, like this year,” he said. He thought that was about the best balance they’d be able to strike—plus, it was easy to do.

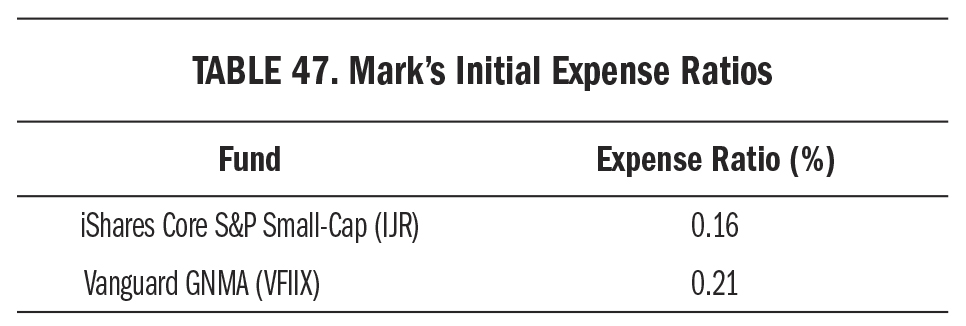

With that, he set up 3Sig in his SnapSheet 401(k). He divided his initial $10,000 along the 80/20 stock/bond allocation you now know well. Since SnapSheet’s plan included iShares Core S&P Small-Cap (IJR) among its choices, and it was the cheapest small-cap index vehicle in the plan, it’s what Mark would use for the stock side. For the bond side, SnapSheet’s plan included Vanguard GNMA (VFIIX), so he’d use that for the 20 percent safe portion of the plan. He’d begin 2001 with $8,000 in IJR and $2,000 in VFIIX. He would build half his $1,215 quarterly contribution into the 3 percent quarterly signal target, leaving the other half in bonds for buying power. If his bond allocation ever reached 30 percent of his account, he would move the extra into IJR on the next buy signal. If the market ever dropped 30 percent on a quarterly closing basis, he would enter the “30 down, stick around” mode and ignore the next four sell signals. That was it. Here’s what he’d pay in expenses:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1yZgBrZ) for a larger version of this table.

Mark’s allocation-adjusted expense ratio came to 0.17, some 92 percent less than Garrett’s 2.00 and 82 percent less than Selma’s 0.92. Already his portfolio enjoyed a distinct advantage. Garrett and Selma didn’t know this, however. Z-val commentators, Peter Perfect, and active managers promise investors that higher fees are more than overcome by better performance, an opinion straight from the old “you get what you pay for” philosophy. Time would tell.

With these preparations, our three investors were off and running at their new jobs with their new 401(k) plans.

Year 1

Everybody’s salary and retirement contributions stayed constant in their first year on the job. The dot-com crash wasn’t quite over yet, it turned out, and the year would introduce a major disruption in September: the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

April 2001

Trouble began early for Garrett. At the end of March, his initial $10,000 plus his three $405 monthly contributions had fallen to an account value of $7,629. At lunch with Selma and Mark, he vented. “I’m down almost twenty-four percent, and that includes the twelve hundred fifteen dollars in new money. I thought Jacob Internet was going to scream higher, and it did in January, with an eighteen-percent gain, but now it’s down forty-six percent since the end of last year when I bought it. I thought the dot-bomb crash was over!”

“You should switch to something safer,” Selma said. “I got burned by Internet junk a year ago, too, so I put together a steadier fund mix this time.”

“I don’t want steady,” Garrett said. “I want excitement.” He chuckled. “Anyway, I’m not doing much better in my other funds. In the first quarter, Wasatch Small-Cap is down eleven percent, and Janus Global Tech is down thirty percent.”

“I don’t know how you stand it,” Mark said. “What are you going to do?”

“Not sure yet. Analysts say tech profits are still bad, and a lot of them think the economy and all corporate profits, not just tech, are going to stay bad all year. I’m thinking I should get to the sidelines and buy back in later, when prices are lower. What about you guys?”

“I’m not doing anything,” Selma said. “My planner and I put together a good portfolio of six funds. My Oppenheimer and PIMCO bond funds paid dividends, and so did Fidelity Growth & Income. I automatically reinvest dividends into the fund that paid them. My funds are safer than yours, so rough quarters like this one don’t do much to them. The dividends and my cash contributions build on top of steady gains. I finished the quarter up five percent overall, so I’m pretty happy.”

Garrett didn’t look happy to hear this, and reiterated his belief that he could catch up later in the year if he got to the sidelines and reentered at lower prices.

“But isn’t that what you tried in December?” Mark asked. “I remember your saying the dot-com crash had made tech stocks so cheap that you wanted to focus on them. Now they’re cheaper. If your goal was to invest in cheap tech stocks, wouldn’t it be better to keep buying the funds you own at these lower prices?”

“Sure, if they’re going to go up soon, but not if they’re going to keep going down. I guess I could play that game forever, couldn’t I? I’ll stay put for a while, keep my contributions steady. What about you, Mark?”

“I just did the only thing I’ll ever do,” Mark replied. Garrett and Selma looked over at him. “No, really. I follow the same procedure at the end of every quarter. I see if my stock fund achieved its three-percent growth goal plus half the cash I contributed to my bond fund for the quarter. If so, I do nothing. If not, I use money from the bond fund to buy the stock fund up to the target balance. If the stock fund is over the target, I sell it down to the target and put the proceeds into my bond fund. That’s all.”

“What did you do this time?” Garrett asked.

“Bought more of my stock fund. It fell six percent, so it missed the target balance for the quarter. The bond fund did fine, though, up almost three percent for the quarter and paying dividends, so I had plenty of cash to catch the stock fund up to its target. My account finished the quarter about eight percent higher.”

“Those are good funds,” Garrett said.

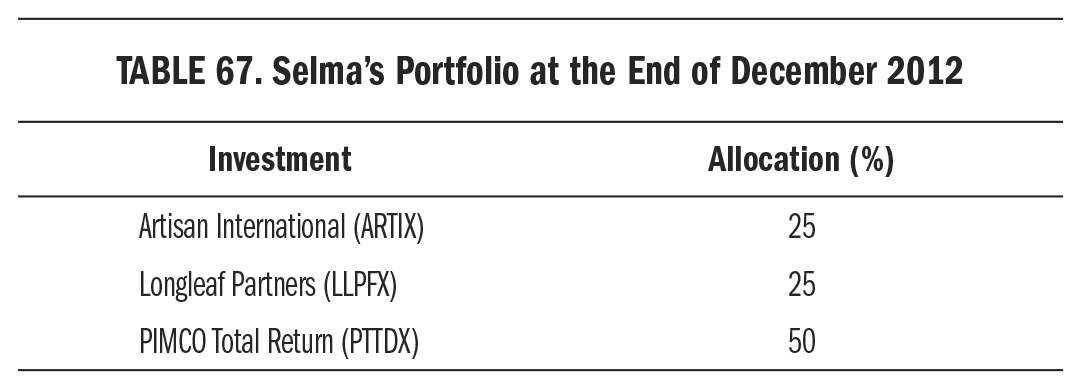

“They’re just indexes. My stock fund tracks the S&P Small-Cap Six Hundred Index and my bond fund owns government GNMAs. Nothing special, and no human judgment involved. I like that. People have terrible long-term track records against indexes; plus they charge more.”

“My fund managers are some of the best in the business,” Selma said. “They beat the indexes. Managers are ranked, you know, so it’s easy to choose good ones. Mine are highly rated.”

“Yeah, Mark, not all people have terrible long-term track records against indexes,” Garrett added.

“Maybe not all, but how’s yours shaping up?”

September 2001

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks shut down the stock market for a week. When it reopened, prices fell sharply, sending poor Garrett’s portfolio to the mat yet again. On the first day of trading after the attacks, Monday, September 17, the Dow fell 7.1 percent and posted its largest single-day point drop in history to that time, and the Nasdaq fell 6.8 percent. Jacob Internet lost 27 percent in September alone, and was off 71 percent for the year. Wasatch Small-Cap Growth was down 6 percent for the year, Janus Global Tech 54 percent. Even though Garrett kept buying the cheaper prices with his monthly contributions, his account value had slipped 26 percent since the beginning of the year.

During a lunchtime walk in a park near the offices, he told Selma and Mark that the amount of money he’d lost in the first nine months of the year wasn’t just the $2,629 difference between his initial $10,000 and his current $7,371 balance. “No, I have to include all my monthly contributions, too.” Run $405 per month for nine months and you get $3,645. He pulled a slip of paper from his pocket. “Total lost, then: six thousand two hundred seventy-four dollars. I’m starting to really hate stocks. First the never-ending dot-bomb bust, now the attacks. Oh, and by the way, Mark, thanks for your swell advice to keep buying cheaper prices back in April.”

“Hey, now,” Mark said. “That’s not my fault. I was just telling you what my signal said, which was to buy more. I bought then, too, you know.”

“Didn’t you sell over the summer, though?” Selma asked.

Mark nodded. “The signal said to sell a bit of my stock fund at the end of the second quarter, yes.”

“How about now?” Garrett asked.

“A big buy signal, what else? You’re not the only person whose stocks are falling. My stock fund dropped sixteen percent last quarter.”

“After you sold the previous quarter?”

“Right.”

“Now you’re going to buy more?”

“Yeah, almost twenty-five hundred dollars more. It’s a big buy signal, at least for me.”

“So, let me guess: you think I should buy more, too.”

“I don’t think anything, Garrett. I just follow the signal. It’s telling me to buy a lot more, so I will. Besides, even if you wanted to buy more, you don’t have the cash, right?”

“Thanks a lot.”

“No, I’m just asking. Is it even an option to buy more?”

“I could at least keep my monthly contributions buying more, but I might not,” Garrett said. “I’m getting fed up with this. The chief economist at Wells Fargo said the attacks have hurt consumer confidence, and it’s costing billions in business activity. I tell you what, my confidence sure is hurting. I’ve just had it.” He walked quietly for a moment. “But your signal says to buy now, right?”

Mark nodded. He didn’t want to say much, preferring just to report the signal. Wasn’t Garrett hearing enough noise as it was?

“I’m keeping my plan going,” Selma said. “I didn’t actually lose badly last month. Artisan and Longleaf went down something like twelve and thirteen percent, but PIMCO gained. With my regular contribution and the dividends, my account value dipped only five percent. It’s important to keep buying when the market dips, Garrett. You pick up more shares on the cheap.”

“I know, I know, but see how you feel when cheap gets cheaper, and cheaper, and cheaper.”

Garrett couldn’t stop thinking about it. He watched investment reports on TV, read investment websites, and devoured the most recent issues of the newsletters he received. His wife mentioned that they were the same newsletters that thought buying cheap tech a year ago was a good idea, and he admitted as much, but said just as all the bears were eventually proved right at the end of the dot-com bubble, so the bulls would eventually be proven right at the end of the current bear market. He wanted to change something but didn’t want to miss out on the big recovery that he just knew lay ahead.

His thinking was confirmed by the media and newsletters. The BBC reported that the “souring U.S. economy further weakened by the recent attacks on the World Trade Center in New York and Washington has erased billions of dollars of wealth among U.S. investors. Many have reacted by pulling what remains of their worth out of stocks and mutual funds, further exacerbating a desperate situation.” As much as he hated the sound of that, he was determined not to join them in the exit stampede. Some analysts suggested it was a perfect time to put fresh money to work. Garrett didn’t have fresh money, but he could rearrange what was already invested.

He was eager to get out of Jacob Internet, even embarrassed to say he ever owned the thing, now down 71 percent year-to-date. Was there a way to bail out of the Internet’s journey to the center of the earth without losing all recovery potential? He thought so when he read that the stock market can do well in a time of war, which the United States entered with a retaliatory strike on Afghanistan and something bigger cooking in Iraq, by all early indications. Apparently, when the United States does well in a war, stocks rise, and nobody expected anything but a positive outcome in whatever Middle East wars resulted from the terrorist attacks. So he should own stocks. Which ones? Airlines.

That’s what one of his newsletters suggested as the sector most poised for a rocket off the bottom. Airplanes were used in the attacks, air transportation was locked down in response, big changes in security procedures were on the way, so airline stocks and related stocks crashed. They wouldn’t disappear, the newsletter said; they would rebound big time when people started traveling normally again, and airlines might even get a helping hand from government. The letter recommended a list of airline stocks, and also the Fidelity Select Air Transportation Portfolio “for investors who’d rather own a basket of stocks than individual picks.” That was it! Garrett would replace Jacob Internet with Fidelity Select Air Transportation Portfolio.

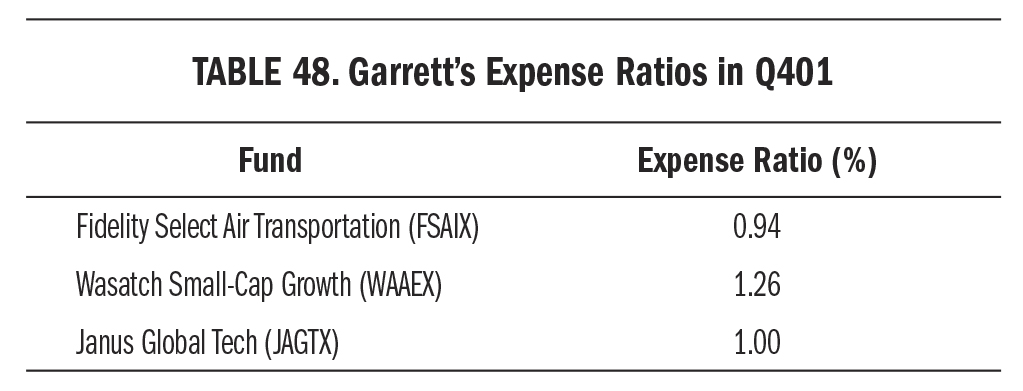

He got on it right away and began Q4 with his new portfolio. On top of what he hoped would be better appreciation potential—how could it be worse?—he would save on expenses. The fee at Jacob Internet had been 2.87 percent. His new Fidelity fund’s expense ratio was only 0.94 percent. With half his capital allocated to this part of the portfolio, the discount represented a big savings. This was his new portfolio’s expense structure:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1CZZ2FU) for a larger version of this table.

As Garrett stayed up late researching and weighing his options, discussing the market with his wife, debating whether war was good or bad for stocks, then which stocks in this particular brand of war would do well, his colleagues did almost nothing.

Selma did literally nothing, allowing her dollar-cost averaging plan to work its magic on the six reliable funds. Terrorist attacks or no, her $405 went into her portfolio per the usual allocations, and she didn’t give stocks another thought after the lunchtime walk with Mark and Garrett.

Mark already knew his signal line for the quarter, which was always 3 percent higher than the previous quarter’s balance in his stock fund, IJR, plus half his quarterly contributions into his bond fund, VFIIX. That quarter, the signal line was $10,620. At IJR’s closing price of $95.50 (unadjusted), he needed 111 shares of IJR. He owned only 85, so he would buy another 26 shares, which would require $2,483. He sold that amount of his bond fund and bought the 26 shares of IJR. He glanced at SPY to see if it had fallen enough to trigger the “30 down, stick around” rule, and saw that it hadn’t. Then, like Selma, he didn’t give the market another thought.

December 2001

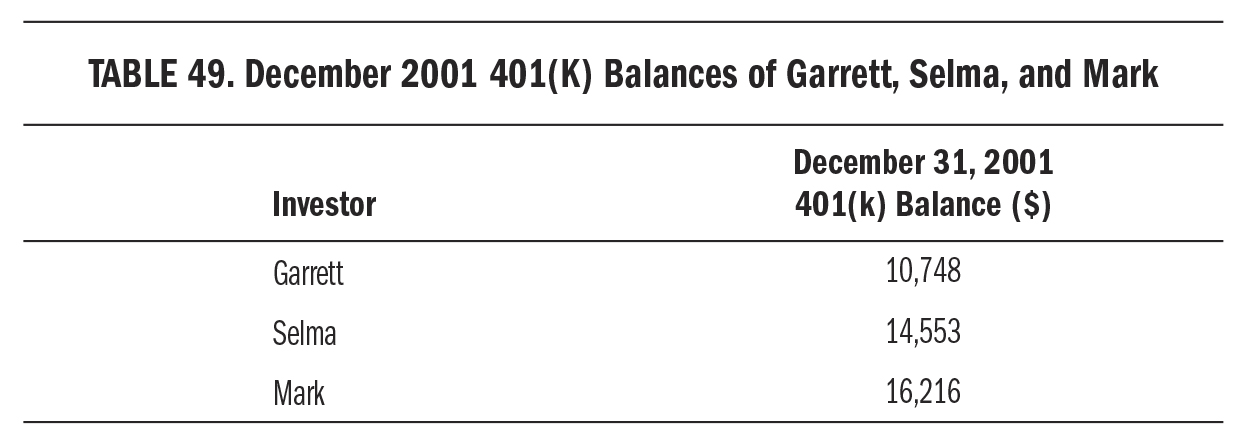

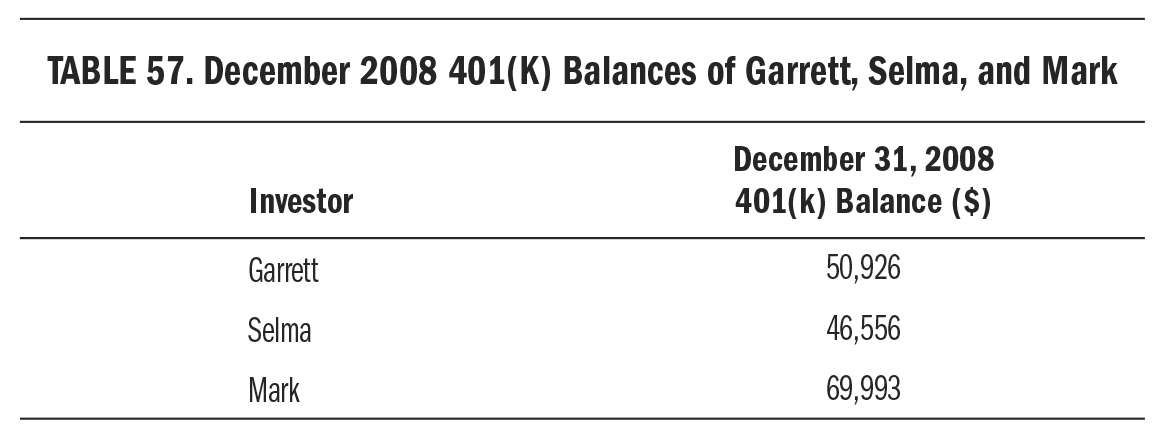

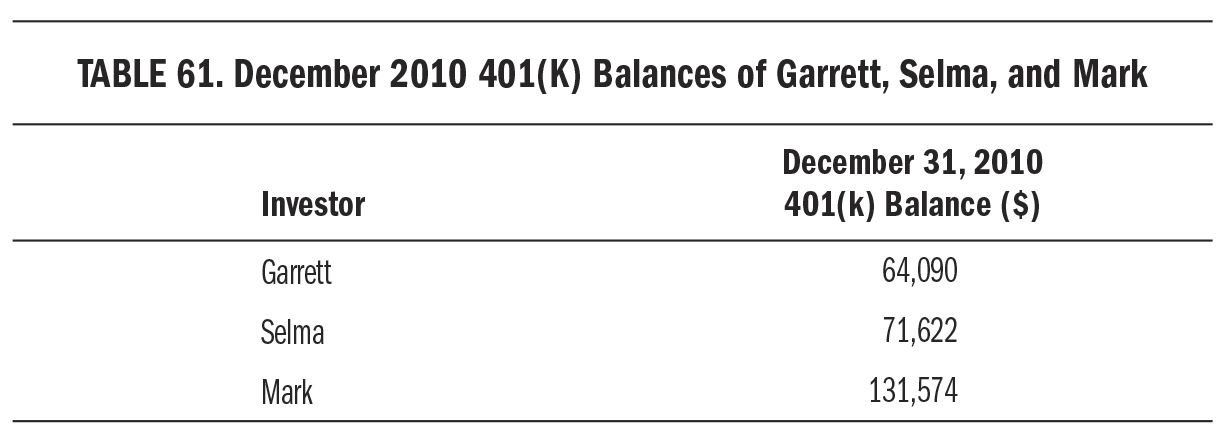

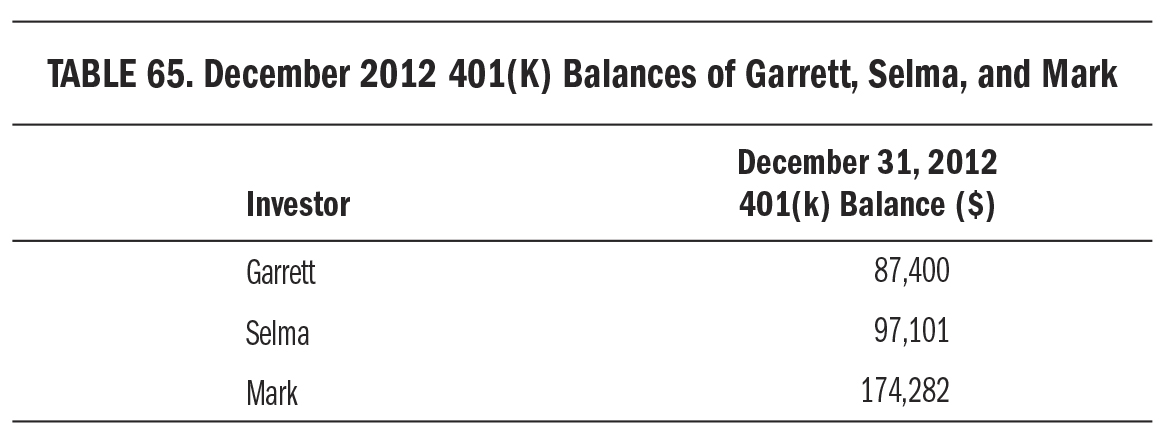

At the conclusion of their first calendar year at SnapSheet, these were the retirement account balances of our three investors:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1zDT27W) for a larger version of this table.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 7 percent in 2001. On top of the terrorist attacks, investment media fretted about the bankruptcy of Enron, with The Economist writing at the end of November that the situation had gone from the firm having a stock market valuation of $60 billion in February to shareholders set for nothing after its bankruptcy. Barely a year earlier, Enron founder Ken Lay was “being touted as the next energy secretary,” but now “his career as an innovative entrepreneur has ended in failure.”

“That’s an interesting sideshow,” Garrett thought, but he was more concerned with his new sector fund, Fidelity Select Air Transportation Portfolio, which gained only 21 percent in the fourth quarter. Jacob Internet, the fund he’d replaced with Air Transportation, gained 51 percent. Even the other funds he kept did better than Air Transportation. Wasatch Small-Cap gained 30 percent, and Janus Global Tech gained 31 percent. He still felt good to be finished with the Internet, but wished he’d held on longer before making the switch.

At least advisers suggesting airline stocks were still bullish. The International Air Transport Association said its Corporate Air Travel Survey had discovered an optimistic business community, with 57 percent of respondents expecting normal travel conditions to resume within six months. Garrett thought this had to be good for airline stocks, so he would hold on to his three funds for a payoff someday.

The fourth quarter was pretty good to Selma. Artisan International gained 9 percent and paid $1.06 in dividends, while Longleaf Partners gained 13 percent and paid $0.52 in dividends. She glanced at her account balance before heading off to a New Year’s Eve party with her children, thought it looked good, and promptly forgot about it.

Mark ran his usual procedure at quarter’s end and was happy to get a decent sell signal, thereby vindicating the previous quarter’s big buy signal. IJR gained 20 percent in the fourth quarter, generating a $1,176 sell signal, which he entered. He would later move the proceeds of the sale into his bond fund. After fifteen minutes of easy calculations and a couple of orders, he was done for the quarter.

Year 2

Everybody’s salary increased by 5 percent in January 2002, to $56,700 per year, or $4,725 per month, pushing their monthly 401(k) contributions to $425 after the employer match. The year would mark an increasing fever pitch in President George W. Bush’s war on terror in Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, which he called collectively “an axis of evil” in his first State of the Union address, and outlined three goals: winning the war, protecting the homeland, and conquering the recession.

It was another ho-hum quarter for Garrett, with Air Transportation up 12 percent but Wasatch Small-Cap down 4 percent and Janus Global Tech down 7 percent. His overall balance, including monthly contributions, rose 13 percent for the quarter, to $12,137. He looked at it positively, though, impressed with his own good judgment to have focused on airlines as they accelerated into a strong recovery. “I’ve figured out a thing or two,” he told his wife over dinner. She asked if he was thinking of taking profits from the “airplane fund.” He said, “No, not yet. I want to give it room to run.” He’d read in Investor’s Business Daily that it’s important to keep winners. Air Transportation was definitely a winner, so he wanted to keep it.

Six months had passed since 9/11. The Associated Press reported, “The Dow has climbed 28.9 percent since its post-attack lows, the Nasdaq is up 35.6 percent and the S&P has advanced nearly 21 percent.” It mentioned that “After two years of unsustainable rallies and tumbling stock prices, there are concerns that some issues have become too expensive given the modest projections for the future. [Some investors] want to hear more companies report improving results before committing too much to stocks.”

Neither Selma nor Mark cared. They paid little attention to the financial media, focusing instead on their family situations. Selma’s account grew 12 percent in the quarter, to $16,243. Mark’s grew 13 percent, to $18,359.

September 2002

In a USA Today article, “Bear Drags Stocks Deeply into Den,” Adam Shell wrote on September 30, 2002, that logic says stocks can’t go down forever, but after watching the Dow Jones Industrial Average sink for three years—nearly 18 percent in the previous three months alone—“countless investors are starting to wonder if stocks will ever go up again.” The Dow and S&P 500 delivered their worst quarterly performances since the fourth quarter of 1987, and the Nasdaq languished at a six-year low.

The z-vals duked it out in the article. The market is “at least in the very late stages of the decline,” said Woody Dorsey, president of Market Semiotics, which specializes in behavioral finance. “We are in a very difficult period, where all of the negative headlines are self-reinforcing.” Bears countered with worries about war in Iraq and “a potentially debilitating bout of deflation” in addition to terrorism, weak corporate profits, and a possible double-dip recession. Until the economy perked up, Donald Straszheim of Straszheim Global Advisors said he expected little more than “sporadic, unsustainable rallies.” Michael Farr, president of money management firm Farr Miller & Washington, said, “The past few years, investors have been rewarded for selling and punished for buying.” Todd Clark, a trader at Wells Fargo Securities, added, “There is an unbelievable amount of pessimism.”

Garrett couldn’t believe it. He flipped through research reports in his home office, looking back at the quarter. Would the stock market nightmare ever end?

A market strategist at Ryan Beck & Co. quipped to the Associated Press, “I think what we’re seeing is a tug of war between one camp looking for the economy and corporate earnings to fall significantly further from where we are, and the other camp looking for the economy to expand . . .” Garrett sighed and pushed back from his computer. “Duh, ya think?” he mocked. “What other choices are there? Here’s an idea: If you don’t know anything, don’t say anything.”

His focused bet on Air Transportation had fizzled, with the fund down 30 percent year-to-date. It had even fallen below what he’d paid for it after the 9/11 attacks, but analysts were still bullish on airlines. “Their day will come,” wrote the newsletter editor who first gave Garrett the idea a year earlier. “We were early, but not wrong.”

“Early but not wrong?” Garrett asked out loud. “Tell that to the guy who walked onto the train tracks after you gave the all-clear. ‘It wasn’t safe then, but it will be later. Sorry.’ Thanks a lot! I’m squashed flat! Sometimes, early is wrong.”

Of course some analysts still said to hold on tight. The recovery that had been “just around the corner” for the past two years was still around the corner. Garrett realized that he was plain sick of it. The same comments from the same people in the same media about the same things hadn’t helped him one bit. He was down and still falling. He knew the best way to guarantee a miraculous market recovery was to sell everything, so he wouldn’t do that. What he would do, though, was stop investing more every month. At least that way, his monthly contributions would build up a buying buffer so he could take advantage of a potentially lower low in the future. If the market didn’t keep falling, he would feel good to have held on to what he already owned. It seemed like a good compromise.

Selma followed her usual action plan, which was to do nothing. Her $425 monthly contribution continued to be divided among her six funds as initially allocated. Even after all the market fuss, her overall account balance including contributions had slipped less than 3 percent since the end of March. No biggie.

Mark followed the signal, as always, but was getting concerned that he might run out of cash. At the end of the first quarter, his bond allocation had hit 32 percent of his account, over the 30 percent threshold, triggering the need to rebalance for the first time. The chance to do so happened the very next quarter, when 3Sig issued the buy signal that gave him the all-clear to rebalance bonds back down to 20 percent.

The market had been bad in that second quarter, pulling IJR down 7 percent. The 3Sig plan issued a signal to buy 16 more shares, or $1,832 worth. Before the order, Mark’s IJR stock balance was $11,712 and his VFIIX bond balance was $7,264. Dividing his bond balance by his account balance of $18,976 showed that he had 38 percent in bonds. He wanted only 20 percent. Multiplying $18,976 by 0.2 showed he should have just $3,795 in bonds. Subtracting this from the bond balance of $7,264 revealed that he should buy $3,469 of IJR instead of the $1,832 indicated by the signal. He sold $3,469 worth of the bond fund, bought the same amount of the stock fund, and began the second quarter with $15,181 in stocks and $3,795 in bonds, perfectly back at the 80/20 ratio that was his target. He then resumed the standard plan, and would stick with it until bonds reached a 30 percent allocation again, triggering another rebalance.

Unfortunately, the market kept falling. Right after the big buy in the second quarter, 3Sig issued another big buy signal, for $3,925 worth of IJR at the end of the third quarter. His contributions to the bond fund had pushed its balance up to $5,204 so he could fund the buy signal, but doing so brought his bond allocation down to only 7 percent. A big enough buy signal in upcoming quarters with no sell signals to help could leave him unable to buy into further price weakness. There was nothing he could do about it, but it reminded him of the idea to keep a bottom-buying account alongside the plan, some extra cash just in case he ever used up his bond fund. He hadn’t set up a bottom-buying account yet. Maybe if he got another raise in the New Year, he would.

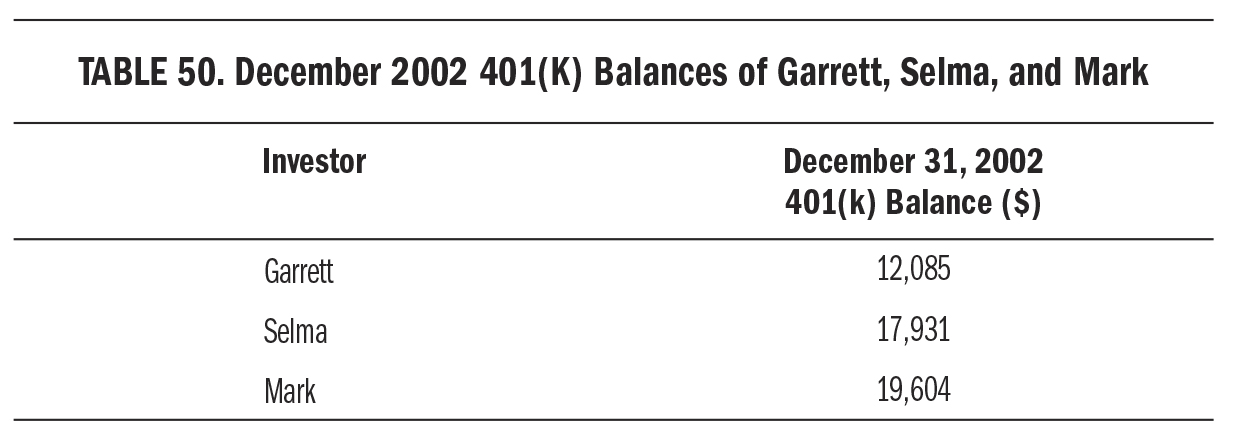

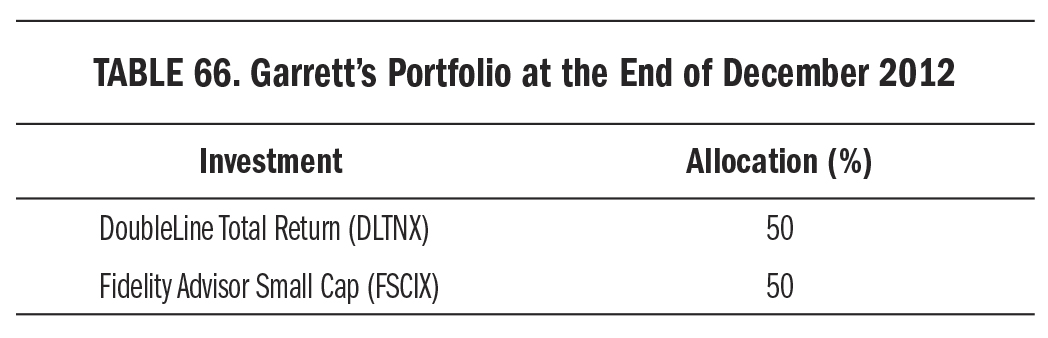

December 2002

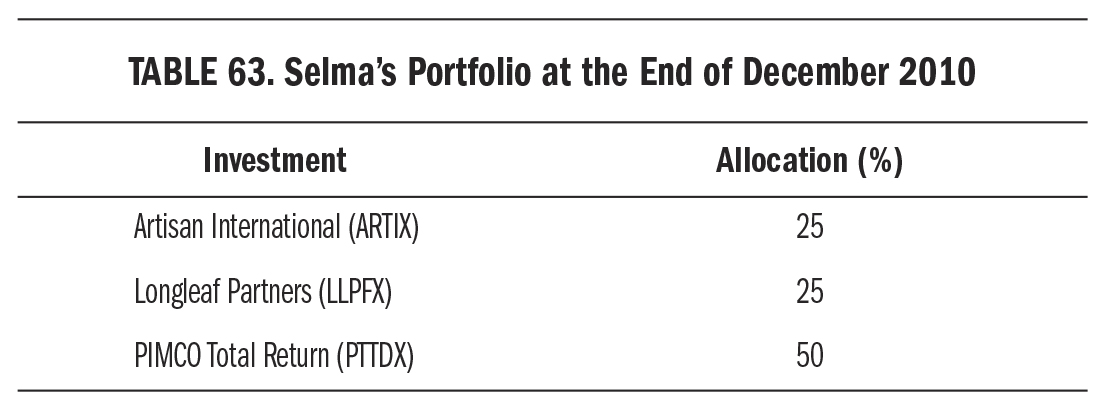

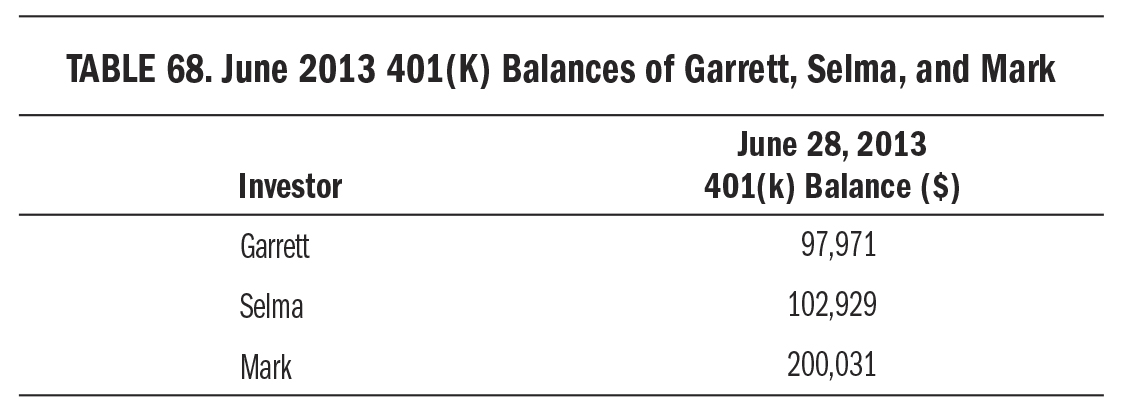

At the conclusion of their second calendar year at SnapSheet, these were the retirement account balances of our three investors:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1EaY25o) for a larger version of this table.

After falling 6 percent in 2000 and 7 percent in 2001, the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 17 percent in 2002. On the Nasdaq, things were much worse: –39 percent in 2000, –21 percent in 2001, and –32 percent in 2002. A Businessweek special report, “Where to Invest in 2003,” began:

Some say Wall Street is a crooked thoroughfare that begins at a churning river and ends in an old graveyard. It’s a fitting metaphor for 2002—the third year of a grisly bear market. There hasn’t been a time in recent memory when the stock market has been so violently roiled, destroying the fortunes of so many. Nor has Corporate America ever been shaken by such an array of scandals. Words like Enron, WorldCom, Adelphia, ImClone, Grubman, Kozlowski, and Fastow have entered the vocabulary as shorthand for corruption and greed. Even Martha Stewart—the Queen of Clean—got her hands dirty in an insider-trading scandal. Things got so bad that Wall Street became a running joke on late-night talk shows. As Jay Leno said: “Do you know the difference between Las Vegas and Wall Street? In Vegas, after you lose your money, you still get free drinks.”

Garrett’s plan to stop investing his monthly contributions felt right. Fidelity Select Air spiked a tad after his decision, but then began falling again in December, down 2 percent. The same happened with his other funds. He liked watching his cash fund build up for the right time to buy later, if there’d ever be a right time. He and his wife set a rule for that year’s Christmas celebrations with family: no stock talk. She was tired of his bad mood that always accompanied such discussions, so asked that they be avoided altogether. He eagerly agreed.

Selma, on the other hand, couldn’t have been happier with her six funds. They kept cooking along, and she continued plowing more money into them every month. All her research two years prior was paying off—the highly rated funds were doing what she’d wanted them to do. If the bear market ever ended, she expected to really see some gains.

Mark was also happy, but a tad nervous about his low bond fund balance as he kept using it to satisfy 3Sig’s buy signals in the bear market. From 7 percent at the end of the third quarter, it rose to 11 percent at the end of the fourth. At least it was rising, but seeing it fall below 10 percent bothered him. He decided he would definitely open a bottom-buying account in the New Year, just to be safe.

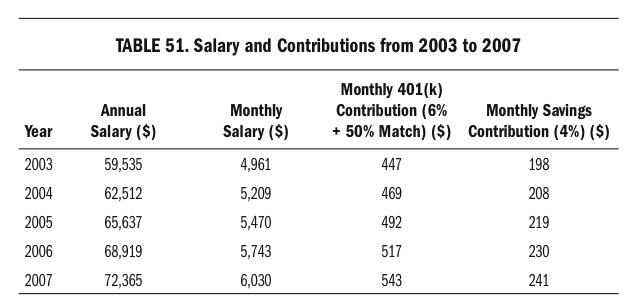

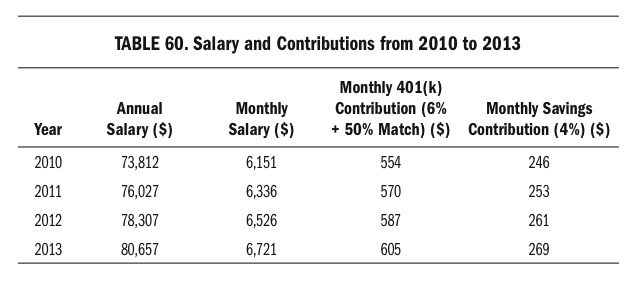

Years 3–7

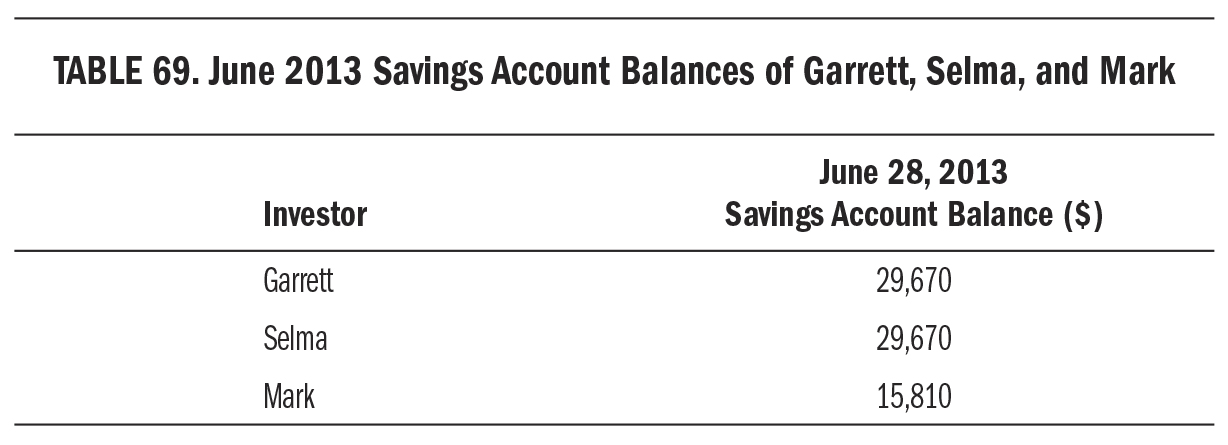

In each of the years 2003 to 2007, everybody’s salary increased by 5 percent. All three of our investors were good at managing their personal finances, and decided to set aside 4 percent of their gross salary in a savings account at SnapSheet’s credit union. They took the modest dividends from these savings accounts out as bonus spending money for a little fun, leaving the balance in the accounts growing at just the pace of their contributions. Here’s how these factors looked over the five years:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1zDT3Zl) for a larger version of this table.

All three considered their savings to be rainy-day funds, but Mark assigned his the extra role of bottom-buying account for his 3 percent signal plan. He soon forgot all about this, however, because after the second quarter of 2003, his bond balance stayed in a comfortably high range, growing from his contributions and the plan’s signals. He kept setting aside 4 percent of his salary as savings, but stopped regarding it as a bottom-buying account to be used if he exhausted his bond fund balance. In the bull market finally under way, there looked to be little risk of a steep crash.

The period didn’t begin as a bull market under way, though. It began with all kinds of uncertainty.

March 2003

The first quarter of 2003 was dominated by the lead-up to war with Iraq. President Bush declared March 17 to be the “moment of truth” for the U.N. Security Council to tell Iraq to disarm immediately or face invasion. Nothing happened at the United Nations, and Iraqi president Saddam Hussein refused to step down, so the United States bombed Baghdad on March 19. The next day, ground troops invaded Iraq. On March 22, the well-announced “shock and awe” air strikes commenced. Finally, the war was under way. During the uncertainty ahead of it, the Dow fell 14 percent from mid-January to March 12. As soon as the start of the war looked imminent, the market turned up.

Garrett, for one, felt like a genius. With nothing but talk of war everywhere the previous Christmas, he’d followed the advice of a cyclical-timing newsletter and switched his Fidelity Select Air Transportation money to the Fidelity Select Defense & Aerospace Portfolio. The fund’s focus on the defense industry not only stood a good chance of thriving in what looked to be a protracted war ahead, given the lack of objectives, but it also charged an expense ratio of just 0.84 percent, compared with 0.94 percent at Select Air.

In the prewar drumbeat, Select Defense fell only 8 percent in the first quarter, compared with Select Air’s 9 percent drop. The slip back was a welcome development for Garrett, who still hadn’t resumed investing the monthly contributions he’d been keeping in cash since the previous October. At the end of a six-month hiatus that saw his cash balance grow to $2,616, he was pleased as punch that he hadn’t lost as much as he would have if he’d kept investing every month. His timing was vindicated, and his confidence increased. To make the move perfect, he just had to deploy his cash at the right moment—and he had a feeling that right moment was upon him. Most of his newsletters said the start of the war would be the start of a bull market. The war had started, and he already owned the only defense industry fund on the market. Bulking up his position in the fund at a low price point in the cycle would make it even better, so he decided to put all $2,616 of his cash into Select Defense at the end of the first quarter of 2003 and resume his regular monthly purchases, too. He’d called the winds of war correctly, and it was finally time to catch up.

Morningstar analyst Kerry O’Boyle confirmed Garrett’s bullishness on Select Defense in a March 18, 2003, review titled, “This Unique Offering Continues to Shine in the Shadow of War,” which began:

Fidelity Select Defense & Aerospace has been drawing quite a bit of attention lately. As the only sector fund devoted exclusively to the defense industry, it can be viewed as a leading candidate to benefit from a war with Iraq. But that would ignore the fund’s long-term outlook, especially with regard to defense-spending trends. Manager Matthew Fruhan thinks that the military is only midway through a building boom required to replace aging equipment, a buying spree that has only accelerated since the Bush administration took office. Whereas a war may provide a short-term boost to defense stocks, it’s this spending cycle that drives defense-company profits.

As Garrett maneuvered his money to benefit from news trends, Selma’s all-star portfolio kept doing everything right, so she continued her tradition of merely glancing at its improving balance and doing nothing. Despite market gyrations in what O’Boyle called the “shadow of war,” Selma’s portfolio with contributions grew 4 percent in the first quarter. She happily noted that, at the current pace, it would soon exceed $20,000 for the first time.

Mark had been watching for SPY to activate the “30 down, stick around” rule in the bear market, and it did so in the third quarter of 2002, by finally slipping under the price that was 30 percent below its quarterly closing high of the previous two years. SPY closed 2000 at $131.19 (unadjusted), putting the rule’s 30 percent level at $91.83. When it closed in September 2002 at $81.79, the level was convincingly breached, instructing Mark to stick around in IJR by ignoring 3Sig’s next four sell signals. The market did badly for two more quarters, causing 3Sig to issue buy signals. The current one forced Mark’s bond balance back down to 7 percent.

That was the last quarter for a long time that a low bond balance would worry him, though. From the $91.48 he paid for IJR at the end of March 2003, its price would rise 74 percent, to $158.85, in the following two years, starting the period with four sell signals in a row that he would ignore per the “30 down, stick around” rule, as his stock and bond balances both rose. IJR would then split three-for-one and go on to rise another 29 percent in the next two years. He had no way of knowing this in advance, of course, and the news continued launching noisemakers every step of the way higher. He didn’t care about that, though. The beauty of 3Sig was that it wasn’t waylaid by worrywarts.

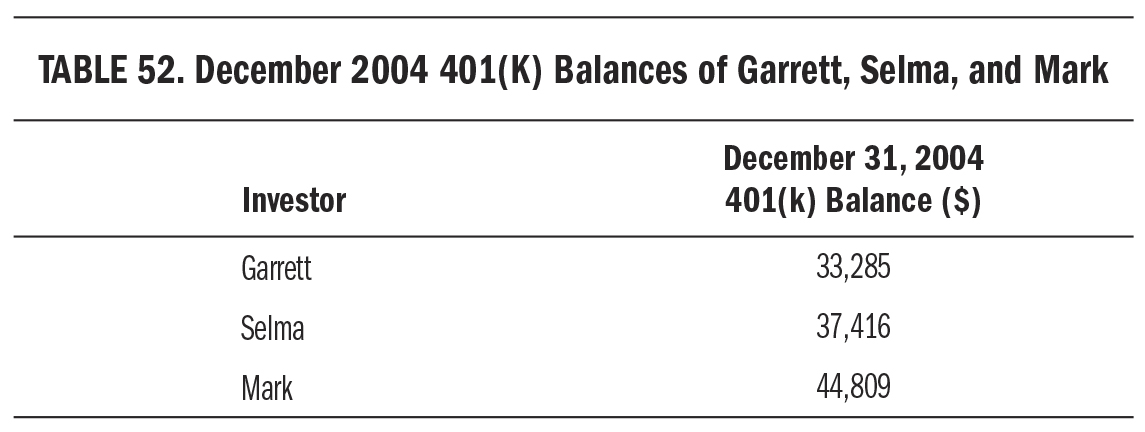

December 2004

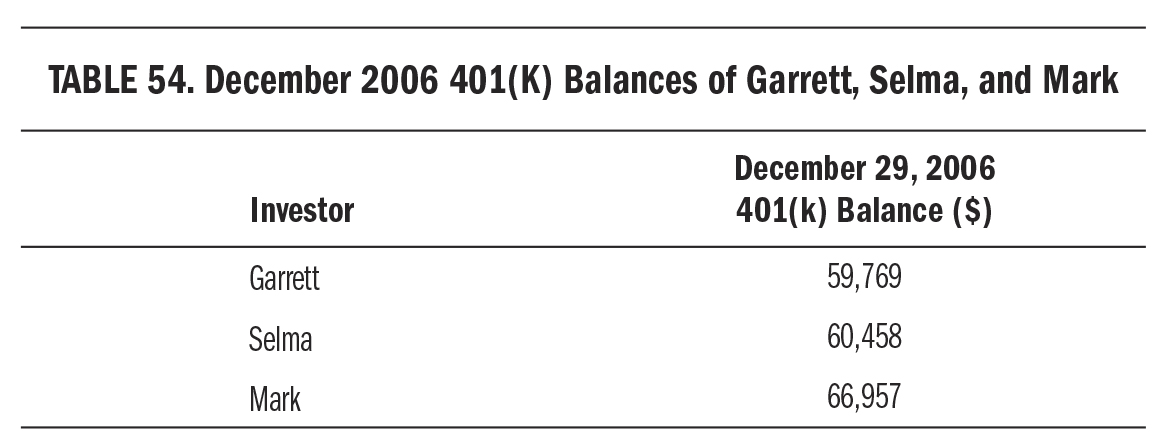

At the conclusion of their fourth calendar year at SnapSheet, these were the retirement account balances of our three investors:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1yDAWRG) for a larger version of this table.

Until he compared balances with his colleagues at a holiday party, Garrett had been confident in his portfolio. Select Defense went gangbusters as the Iraq War dragged out. After President Bush changed the war’s objective from finding nonexistent weapons of mass destruction to building democracy in a country that didn’t want it, defense analysts became giddy with glee because such a mission would never be accomplished. What could be better for defense profits than a war without end? Garrett’s extra investment in Select Defense back in March 2003 paid off as the fund rose 78 percent by the end of 2004. His other funds did well, too. In the same time period, Wasatch Small-Cap grew 61 percent and Janus Global Tech grew 52 percent. Yet here he was way behind Selma and Mark, who never did anything interesting in their accounts.

He dove back into his market research and discovered an energy newsletter pushing oil refiners and drillers because their shares had done well recently. Then he found Richard Bernstein, the chief U.S. strategist at Merrill Lynch, telling Businessweek that stocks would go up only a little in 2005, about 1 percent plus a couple of percent from dividends. “It could be a rough ride even for that,” Bernstein warned. “The Federal Reserve is going to be tightening short-term interest rates at the same time profit growth is slowing down to about half the 18 percent we’ve been getting in 2004. That’s a coincidence that never ended well under [Fed chairman Alan] Greenspan. It contributed to the early-1990s recession, the 1998 financial crises, the deflation of the tech bubble, and the last recession.” He liked the energy industry because “prices will cycle up and down, but the secular trend is higher.” He suggested avoiding refiners and drillers. “It is better to hide out with big, reliable guys like ExxonMobil.”

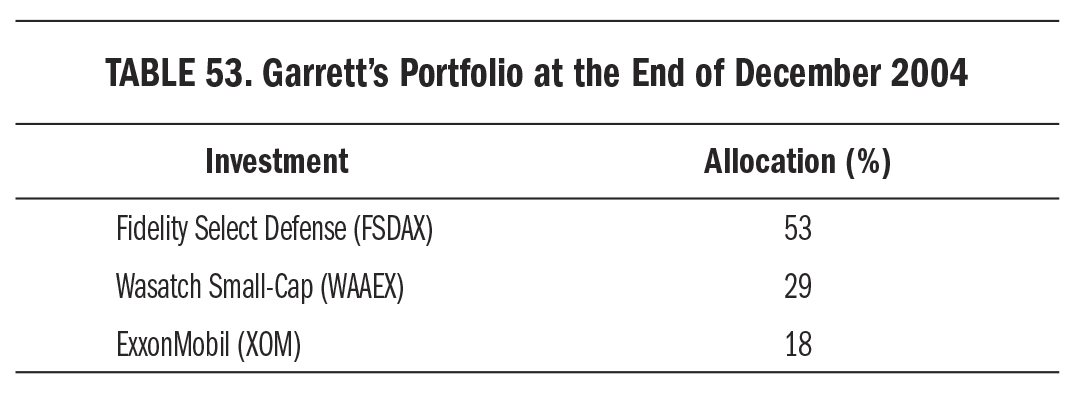

After serious thought and dinner conversations with his wife, Garrett decided he would sell his position in Janus Global Tech, his overall laggard, and put the proceeds into ExxonMobil stock. He’d keep his monthly contributions divided up the same way, with half going into Select Defense and a quarter into each of Wasatch Small-Cap and his new ExxonMobil holding. Maybe his problem had been too much diversification, he thought, and by concentrating a portion of his account on a single stock, he would do better. After all, Bernstein called energy “the No. 1 story for the decade” and seemed to think ExxonMobil would lead it. The stock had nearly kept up with Janus Global Tech since March 2003, and paid a steady quarterly dividend, so Garrett thought its outlook was decent. At the end of December 2004, then, his portfolio became this:

Visit (http://bit.ly/15mwkU2) for a larger version of this table.

Selma was surprised to find herself wondering if her all-star portfolio wasn’t as great as she’d thought. Mark didn’t do much more than she did, and used only two dirt-cheap index funds in the signal system he was always citing as an excuse to avoid stock talk. Whenever Garrett or another colleague started repeating forecasts they’d heard on TV or read somewhere, Mark would hold up a hand and say, “I have no opinion and couldn’t care less. I just follow the signal.” For a while it had been impressive enough that his signal stayed slightly ahead of her all-star portfolio. Now it was no longer just slightly ahead; it was 20 percent ahead. She read more about her funds in the investment media to see if she’d gone wrong somewhere. It didn’t look like it. Consensus expected ever better results from the likes of Mason Hawkins and Bill Gross, so she decided that, for the time being, she’d keep on keeping on. For the first time, however, she did so with a twinge of doubt.

As for Mark, he couldn’t have been happier. His bond balance hit 25 percent that quarter, and he wondered if he’d soon need to move extra bond money into stocks again. When the only challenge he had to contend with was shifting an abundance of bond balance into a surging stock balance, life was good. How much time did he spend listening to z-vals and others paid to make noise for a living? Zero—and he was beating them all.

September 2005

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana, causing severe damage to that state and the Gulf Coast from Florida to Texas. The levee system in New Orleans failed, allowing the flooding of 80 percent of the city and prompting a lawsuit against the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for its role in one of America’s worst civil engineering disasters. The storm killed more than 1,800 people and caused more than $100 billion in damage, making it the costliest hurricane in U.S. history.

Chris Isidore at CNNMoney warned on September 6 that “higher gasoline prices aren’t the only economic fallout from the devastating storm. Real estate and home construction, trade, agriculture and livestock—even the purchasing power of the dollar—are all likely to be impacted by the storm in the coming months.” Worse, it seemed a recession was in the cards:

The prospect that the U.S. economy will significantly slow is one reason many investors and analysts now believe the Federal Reserve may not raise rates at its Sept. 20 meeting, which would be the first time since May 2004 it left rates unchanged.

But there are growing concerns that the combination of higher energy prices and some transportation disruptions, coupled with lower economic activity in the Gulf region itself, could be enough to plunge the economy into an actual recession. . . .

“I don’t think it’s too soon to talk about a recession, even if I still think there’s less than a 50-50 chance,” said Doug Porter, deputy chief economist of BMO Nesbitt Burns. “Every other recent recession has been preceded by an energy shock. Certainly at the least there is a risk that growth will be curtailed.”

Garrett smiled. Energy shock? No problem. He owned ExxonMobil, which had risen smartly along with oil prices. Since he bought it at the end of December, the stock had gained 24 percent and paid $0.85 in dividends per share. It now comprised 21 percent of his portfolio, even though his other two holdings were up a lot, too.

Selma and Mark were also doing well. None of the three investors saw any cause for concern in his or her 401(k), but just to be sure, both Garrett and Selma asked Mark about the current signal. “A very tiny sell,” he reported; “less than ten dollars. It’s saying to stay put.” That’s what they all did.

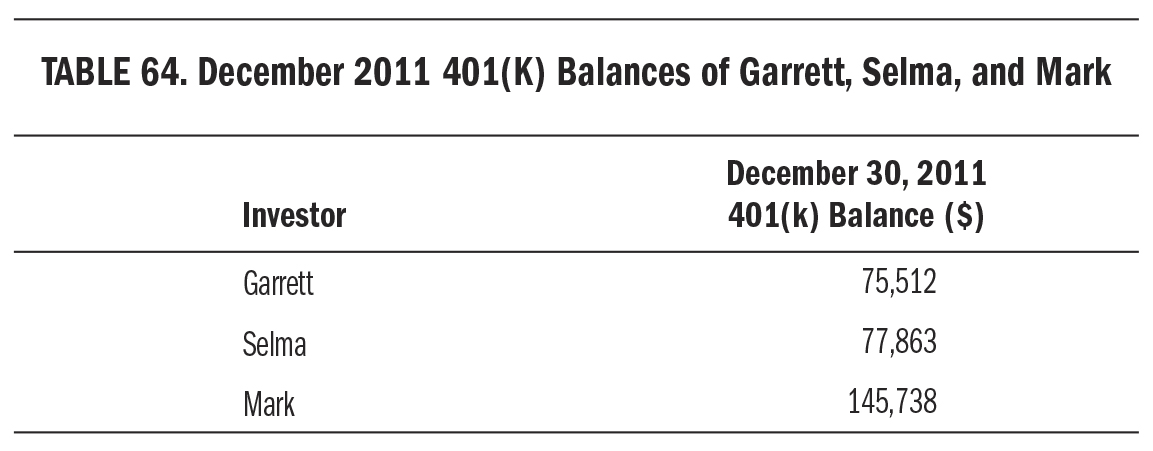

December 2006

At the end of their sixth calendar year at SnapSheet, these were the retirement account balances of our three investors:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1ySXSeB) for a larger version of this table.

This came as a shock to Garrett, still in last place even after watching his account balance grow 36 percent that year, from $43,805 to $59,769. Select Defense rose 11 percent and paid a whopping $6.61 in dividends for an 8 percent yield. Wasatch Small-Cap was up only slightly but paid $2.92 in dividends. ExxonMobil rose 36 percent and paid a $0.32 dividend every quarter. It was nothing but up, up, and up, yet he hadn’t kept pace with his do-nothing colleagues. How well had their positions done?

Selma’s Longleaf Partners fund rose 13 percent and paid dividends, her Artisan International fund rose 15 percent, and her other funds did well and paid dividends, too. Mark’s IJR small-cap index rose 14 percent and paid a dividend, while his bond fund was flat but sported a 5 percent dividend yield. These weren’t amazing performances, but somehow Selma had outpaced Garrett, while Mark’s quarterly signals extracted enough extra profit from the performance of his funds to put him even farther ahead.

Just about the time Garrett plotted what he could do to sprint ahead of Selma and possibly overtake Mark, another colleague of theirs, whom we’ll call Peter Perfect, began bragging about his investments. Peter told Garrett, “I’m killing it with First Marblehead. The thing occupies a sweet spot inside a sweet spot, taking advantage of loan securitization but with student loans, not subprime. This credit boom has most people eyeing mortgages, but the really smart money is in student lending. These guys take a basket of student loans, turn it into a tradable security for a huge fee, then sell it off. Almost no risk. It’s brilliant.”

“Has the stock done well?” Garrett asked.

“Well?” Peter said, laughing. “You could say so. I paid thirty-five dollars for it a year ago. It was seventy-five earlier this month, and just split three for two.” He let that sink in, then elbowed Garrett and added in a lower voice, “It even pays a dividend every quarter.”

“All the profit’s probably gone,” Garrett said.

“I doubt it. Fundamentals are rock solid. P/E is only thirteen, profit margin is a fat forty-six percent, revenue growth is seven hundred sixty percent, it has two hundred sixty-five million in the bank and almost no debt, and insiders own a third of the company. At least you know if it goes down, the people running the place are going to go down with it, right?”

“Right. Are you buying more?”

“A lot more.”

Garrett confirmed that Peter got First Marblehead’s fundamentals right. All the research he could find on the stock was positive, except for a few analysts worried about overvaluation after the stock’s recent rise. Business had never been better for the company. It just closed a $1 billion securitization of private student loans originated by several banks under different loan programs structured with the help of First Marblehead. He read in the most recent 10-Q (a quarterly report that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission requires public companies to file) that Marblehead was shielded from lending risk because it did “not take a direct ownership interest in the loans our clients generate, nor do we serve as a lender or guarantor with respect to any loan programs that we facilitate.” It made money only from “the volume of loans for which we provide outsourcing services from loan origination through securitization.” This seemed promising, what with the cost of college rising exorbitantly, all but guaranteeing demand. Marblehead looked like the ultimate middleman between borrower and lender, making mega profits with minimal risk.

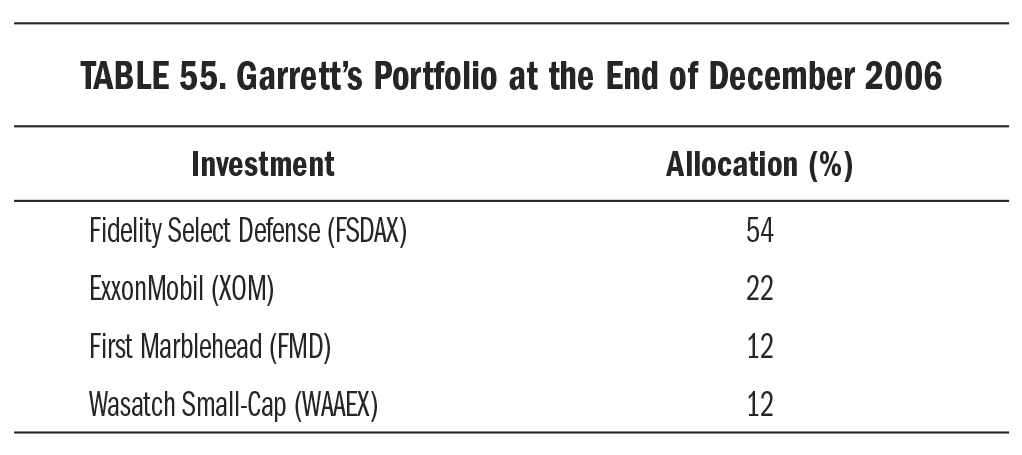

At the end of December 2006, Garrett moved half his Wasatch Small-Cap allocation into First Marblehead stock. Wasatch was his laggard; ExxonMobil, his leader. Maybe another smart stock pick could become a leader, too. Prospects for Marblehead looked even better than those for ExxonMobil, and Garrett thought he might just lead the 401(k) pack with this addition. His new portfolio became:

Visit (http://bit.ly/15xHu92) for a larger version of this table.

As for Selma and Mark, they were both pleased with the progress of their portfolios in the bull market, and Mark was surprised to find himself cruising comfortably ahead of Selma. He knew that in a long enough bull market he could fall behind an unwavering, fully invested portfolio, but was reminded by Selma’s position in second place that the full investment needed to focus on high-performing stocks, such as his small caps in IJR. Selma was proving to be nothing if not steadfast, and she had certainly done her homework in selecting the best of the best funds, but she had diversified beyond high-performing categories. Would her team of pros prove their worth in the quarters ahead?

September 2007

News about the troubled housing market was everywhere. A Barron’s article titled “Getting Ready for the Roof to Fall” looked at the strategy of bond fund manager Jeffrey Gundlach, the chief investment officer of TCW Group: “He sees U.S. home prices dropping an average of 12 percent to 15 percent annually from the highs achieved last year and not reaching their eventual trough until late 2008, at the earliest. And they may not start recovering until 2010 or 2011, inflicting, in the meantime, real damage on the economy.”

Gundlach thought the downward trend in mortgage delinquencies and foreclosures would accelerate. “That’s because next year and early 2009 will see a crescendo in the troubled 2006 and early-2007 subprime mortgage vintages reaching their two-year rate reset points, when the low teaser rates expire. Facing jumps in monthly payments of 30 percent or more, many homeowners are likely to just throw in the towel and default on their mortgages.”

Maybe, Garrett thought, but it sure looked like the Federal Reserve was ahead of the curve in supporting the economy. It cut the federal funds rate by 0.5 percent, to 4.75 percent, on September 18, which sent stocks up sharply. He’d read an article in Barron’s a month earlier titled “A Contrarian Should Be Bullish on Stocks,” in which investment newsletter watchdog Mark Hulbert wrote that the stock market’s 7 percent drop from early July to early August, “painful as it undeniably has been, is not likely to be the beginning of a major bear market.” Hulbert reasoned that since the average investment newsletter had turned bearish, it was time to do the opposite, because “a contrarian would conclude that the current sentiment picture does not conform to the typical psychological profile of a major market top.” He suggested that investors think of it this way: “The editor of the average market-timing newsletter is more often wrong than right at market turning points. To be bearish right now requires you to bet that this time he will uncharacteristically get it right. Is that really how you want to bet?”

It wasn’t how Garrett wanted to bet, so he stayed put. From the end of July to the end of September, his account grew 11 percent, to $74,092 from $66,756. That was with a little help from the Fed, true, but wasn’t that legitimate? The Fed always has the market’s back. It’s one of the long-term reasons to stay bullish, he figured. Following the half-point rate cut, USA Today reported, “The Dow soared 335.97, or 2.51 percent, to 13,739.39. The last time it rose more than 300 points in one session was Oct. 15, 2002, when it gained 378 points, and Tuesday’s percent increase was the biggest since April 2, 2003. The blue-chip index is now only about 1.9 percent below its record close of 14,000.41, reached in mid-July.”

Garrett’s First Marblehead bet had gone south, down 31 percent since he bought it the previous December, but it had shot 15 percent higher since July and had grown its dividend from 15 cents in March to 27.5 cents in September. It was still recommended by the Motley Fool Hidden Gems newsletter, and nineteen hundred out of two thousand investors in the Motley Fool CAPS research community thought First Marblehead would beat the market. The company announced earlier that month that its most recent sale of asset-backed securities would raise almost $3 billion. Everything was on track for a good recovery, and Garrett felt fine putting more money into the stock at lower prices. He allocated 12.5 percent of every monthly contribution to it, and would continue doing so.

Besides, his other picks were more than making up for Marblehead’s struggles. Year-to-date, Select Defense gained 18 percent; ExxonMobil, 21 percent; and Wasatch Small-Cap, 9 percent. Once the market caught on to Marblehead’s outstanding business results and reinvigorated the stock, his portfolio would fire on all cylinders and he’d mount some serious profits.

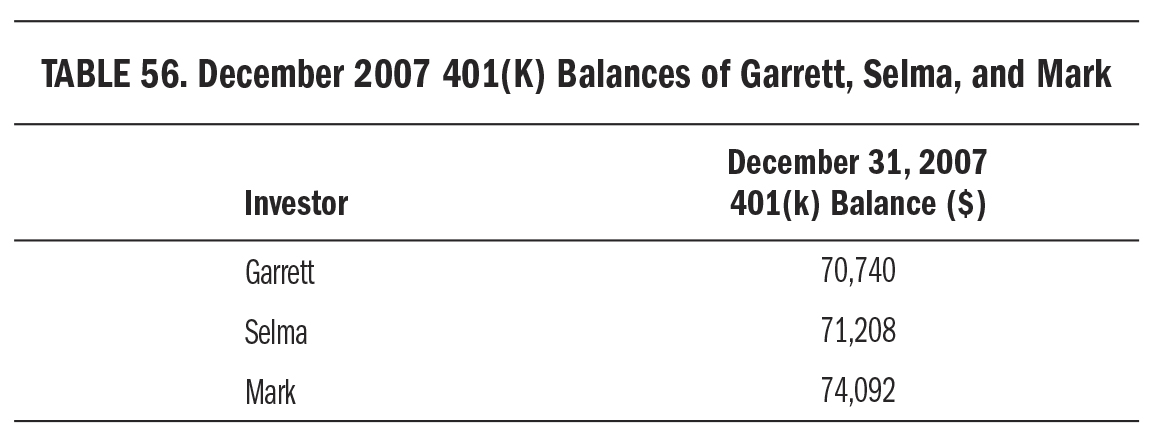

December 2007

At the end of their seventh calendar year at SnapSheet, the 401(k) balances of our three investors stood as follows:

Visit (http://bit.ly/1AZRJLI) for a larger version of this table.

Both Garrett and Selma had narrowed the gap between their balances and Mark’s. Selma’s all-star portfolio seemed to be proving that high expense ratios were worth it, and that careful research of active management track records and sticking with a plan were the keys to profiting over the long term. She was still ahead of Garrett and looked destined to surpass Mark, with no effort.

Garrett wasn’t as upset as he had been at the ends of other years, now that all his hard work had finally paid off. He’d basically kept pace with Selma’s famous fund managers and was closing in on Mark’s smug signal, and that was after First Marblehead nearly gave up the ghost in the fourth quarter, crashing 60 percent. He wasn’t sure what was going on there, given that the company had nothing to do with poisonous subprime lending. All the Marblehead bulls kept insisting that the market was throwing out the baby with the bathwater and suggested averaging into lower prices for an eventual recovery, so Garrett kept his plan going. There wasn’t much risk left anyway, because Marblehead had dwindled to just 3 percent of his portfolio. Even if it blinked out entirely, it wouldn’t matter a whole lot.

Everybody felt fantastic that holiday season, as most investors do at the tail end of bull markets. Mark rarely thought about stocks, but with everybody around him bragging about their bang-up performances, it was hard to ignore them. Garrett had become especially noisy, chiding Mark for ending the quarter with a fifth of his capital in bonds. “I’m still ahead of you,” Mark said, to which Garrett replied, “Not by much anymore.” He never missed a chance to remind Mark that stocks mostly go up. If anybody ever mentioned the dot-com collapse, Garrett retorted, “And what came after it? A raging bull. Money needs to be put to work.”

The signal had been telling Mark to buy most of the year, including that quarter. The only sale was in the second quarter, and it was a modest one. He noticed that IJR had been steadily moving lower since then, to the tune of –9 percent since the end of the second quarter. The next two quarters of buying lowered his bond balance from 27 percent of the portfolio to 20 percent, where it stood after the fourth-quarter buy. At least the signal was moving more of his bond allocation into stocks, the asset class everybody loved talking about. Something was odd, though. If stocks were so great, why had IJR been falling for six months?

He mentioned his thinking about the signal to his wife, one of the rare times he let stock talk invade their home. They agreed that growing the account to $74,000 in seven years without paying any attention to all the fuss on Wall Street was pretty darned good, and better than most. They decided to leave 3Sig to its own devices.

Garrett asked Mark what the signal was saying at the end of December 2007. “To buy,” Mark answered. “A fair amount, too: sixty-four hundred dollars.”

Garrett clapped him on the shoulder. “It’s good to see that signal trying to stay ahead. Most of my newsletters are bullish, too, so your signal is probably right.”

“It’s been mostly right so far. What are your newsletters saying?”

“That we’re going to make more money. I’ll e-mail you some highlights later.” Garrett’s note arrived full of bullish commentary from pundits, interspersed with his own analysis emphasizing quotes and tossing in phrases showing he’d been onto the bull market from the start: “as I expected” and “which was obvious” and “as anybody paying attention could see” peppered the connecting material.

Bob Brinker wrote in the early December issue of his Marketimer newsletter that the stock market’s recent sell-off was good news. “The short-term correction that began in October and continued into November has served as a health-restoring pullback, and has paved the way for new record highs in the S&P 500 index in our view.” Garrett agreed because anybody paying attention to history could see that the market never rose in a straight line. It needed to take a break from rising to avoid getting overbought, he explained.

In the December 6 issue of The Chartist Mutual Fund Letter, editor Dan Sullivan wrote, “What we find remarkable and most encouraging is the fact that the market has been able to make upside progress in the face of extremely adverse news. If history is any guide, this bull market has further to run. We say this because at bull market peaks, the news is highly favorable and the public is jumping in with both feet. Currently, the public is apprehensive with the financial press painting a very bleak picture. This is more indicative of a market bottom than a top.” He kept the letter’s portfolio fully invested.

Garrett added his two cents: “Sullivan is right. Retail investors are too negative here. The time to get out will be when they’re all bullish. There’s more upside ahead in 2008.” He liked what an investor friend of his observed on this score: “We may be at the beginning of the end of this bull run, but not the end of the end.”

Stephen Savage at the No-Load Fund Analyst stayed fully invested, too, because “our valuation work continues to suggest that large-cap U.S. stocks are at least reasonably valued under a broad range of likely growth scenarios. We continue to expect stocks to outperform bonds over our five-year tactical time horizon.” Garrett said his analysis also indicated that stocks were not yet overvalued. “Besides,” he added, “valuation almost never causes a crash.”

Even the Value Line Investment Survey thought stocks could rally in 2008 if “the economy steadies itself and corporate earnings press forward even modestly.” It kept its recommended stock allocation at 75 percent, where it had been since June. Garrett said the odds of profits being “considerably better than modest” were very good. “Don’t fight the Fed,” he advised, “especially when it’s working overtime to keep stocks rising.”

Then came 2008.

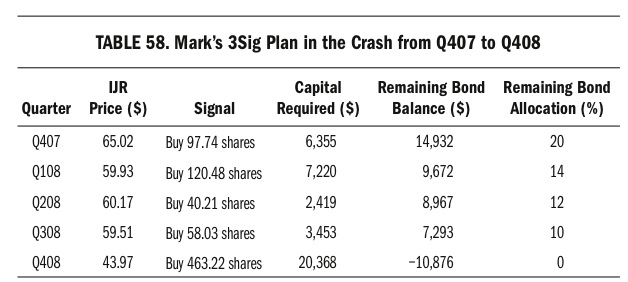

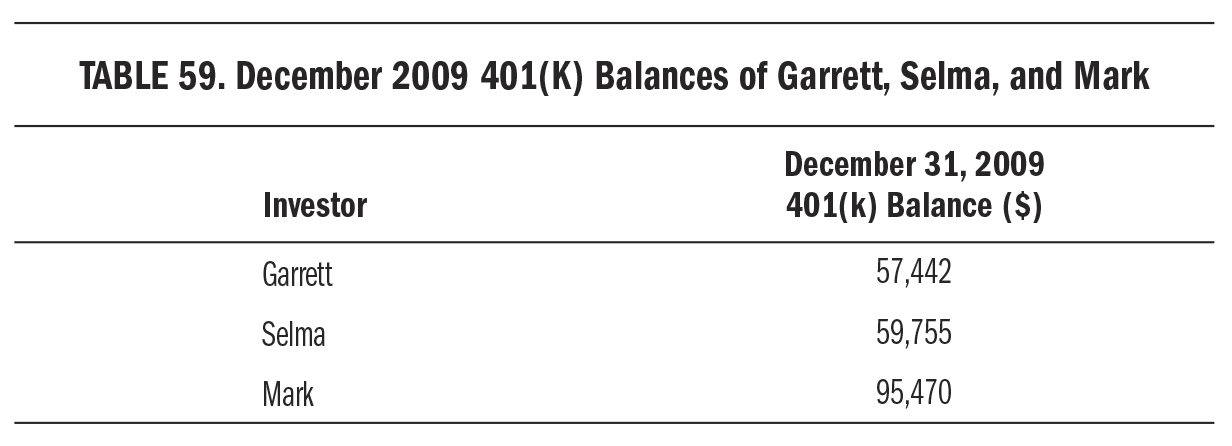

Years 8–9