2

TRIAL BY FIRE

IT TOOK THE H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth, the largest passenger liner afloat, only five days to transport 15,000 men of the 106th Division from New Jersey to Glasgow, Scotland, making port on 17 November 1944. The troops were then taken by trains to Portsmouth, England, and transported across a storm-tossed English Channel to France and up the Seine River. The young soldiers of the “Golden Lion” Division who had hoped to spend a few days in Paris were disappointed. The division was loaded like cargo into hundreds of unheated trucks and hauled eastward, crossing into Belgium on 10 December. The troops did not see Paris.

What they saw instead from the backs of their “deuce-and-a-halfs” (cargo trucks) was a burnt and broken landscape that bore grim testimony to the ferocity of the no-holds-barred type of fighting that had taken place for the past six months. Hardly a town, village, or bridge was left intact; the ruins of homes, shops, churches, and factories—the enormous reality of which exceeded a thousand-fold what the young soldiers of the 106th had seen in newsreels or read about in newspapers—spoke mutely of the desperate battles that had been waged across the continent.

A member of the 106th Infantry Division stands guard in the snowy Ardennes region of eastern Belgium. (Courtesy U.S. Army Military History Institute)

Scattered along the roadsides and in the fields were the twisted and blackened carcasses of tanks, trucks, halftracks, ambulances, artillery pieces, jeeps, aircraft, and military hardware of all kinds. And not all of it was German; plenty of wrecked and blood-stained American vehicles littered the fields, farms, roads, and towns. The men of the 106th collectively gulped and hoped that things were considerably quieter wherever they were going.

On 11 December, the Golden Lions, half-frozen from their long, wintry ride across France and Belgium, found themselves detrucking in St. Vith, a quaint, east Belgian town that had existed for over 600 years. It didn’t look too bad here. In the center of town stood the impressive Pfarrkirche, while the Büchelturm, a stone tower that had been part of the landscape since 1689, provided a picturesque glimpse into the town’s medieval past.

The town was almost as old as Europe; named in honor of the martyr St. Vitus, the first settlers had put down roots in the area in 863 A.D., although there is evidence of much earlier settlement. In the twelfth century, St. Vith began building its reputation as an important market town for produce and manufactured goods. Over the centuries, the town was ruled by many nations—Spain, Austria, and France, to name but three—and has found itself in the center of numerous wars, during which it was destroyed and rebuilt many times.

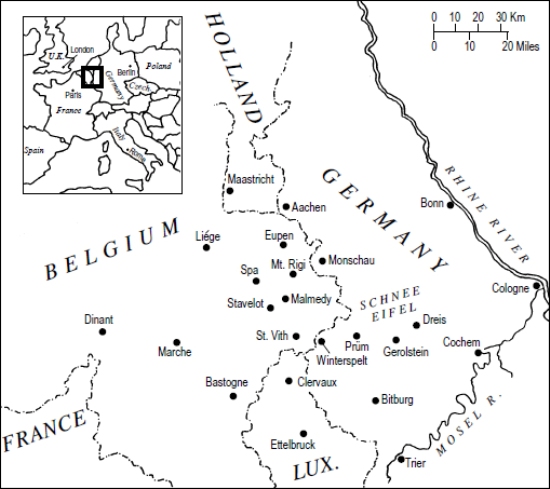

The intersection of Belgium, Luxembourg, Holland, and Germany— site of the “Battle of the Bulge.”

After the Congress of Vienna remapped the Continent following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the town became part of Prussia (even today, St. Vith’s official language is German). In August 1914, St. Vith found itself in the path of Kaiser Wilhelm’s armies as they swept through on their way to the Somme and beyond. When Germany was stripped of her conquered territories at the end of World War I, St. Vith was restored to Belgian control. This status remained in place until July 1940, when German troops plunged across the border in Hitler’s surprise invasion of France through the Ardennes Forest. Banners bearing the swastika hung from the town’s buildings, and St. Vithians, perhaps hoping that a friendly welcome would spare the town from destruction, stood on the street corners and greeted the first panzers with the stiff-armed Fascist salute.

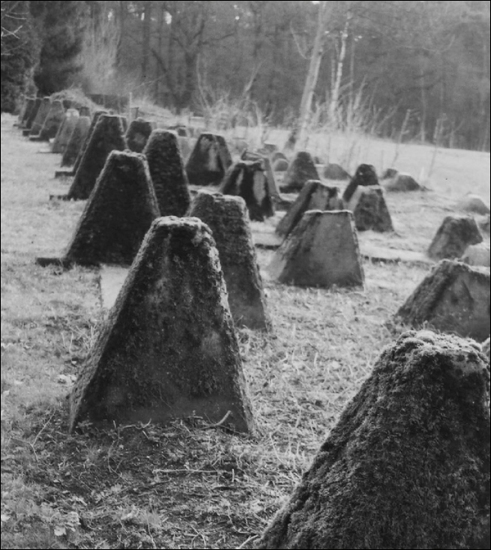

Concrete “dragon’s teeth” anti-tank obstacles along the German-Belgium border near Aachen. (Author photo 2004)

And now, at the end of 1944, with Hitler’s armies having been forced out of France and Belgium by the advancing allies, St. Vith again became a vital and attractive prize for both sides.1

This eastern part of Belgium is the country’s least populous. The broad farmlands and thick groves of trees are spread over a series of rolling hills and deep river valleys, intercut by narrow, winding roads. At St. Vith, just north of Luxembourg, the Ardennes Forest of Belgium melds with the Schnee Eifel region of Germany; the two areas are indistinguishable from one another. To call the region “mountainous” would be to use a misnomer; while steep in places and heavily forested in others, the region’s undulating terrain is perhaps more akin to the gently rolling Appalachians of central Pennsylvania than the Alps.

A high, tree-covered ridge that runs basically from the northeast to the southwest, the Schnee Eifel was, in 1944, heavily fortified with reinforced-concrete bunkers, pillboxes, and anti-tank “dragon’s teeth” obstacles—part of the Germans’ Westwall defensive line. As the official Army history of the campaign says, “The Eifel is thickly covered with forests and provides good cover from air observation even in the fall and winter. The area has no large towns but rather is marked by numerous small villages, requiring extensive dispersion for any forces billeted here. The road net is adequate for a large military concentration. The rail net is extensive, having been engineered and expanded before 1914 for the quick deployment of troops west of the Rhine.”2

On 7 December 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, head of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, met with his highest American and British commanders in Maastricht, Holland, to map out plans for future operations. Autumn’s broad Allied push had come to a dead stop along the German-Belgian border at Aachen and the Hürtgen Forest, as well as elsewhere along the front, due to a variety of factors: bad weather, heavy casualties, a serious shortage of fuel and ammunition, increased German resistance, and plain exhaustion. It was decided that a fresh offensive, set for early 1945, must be mounted in order to keep the German defenders on their heels and prevent any further loss of offensive momentum.

By the middle of December 1944, the Allies held a 400-mile front—from Nijmegen, Holland, in the north, to the French–Swiss border at Basel, in the south. Occupying the northern front, or left flank of the Allied line, were British Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s Twenty-first Army Group, composed of the First Canadian and Second British Armies; General Omar Bradley’s Twelfth Army Group occupied the area to the south. Lieutenant General William H. Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army was squeezed into a small sector from west of Jülich and south to Aachen, while Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges’s First Army had the broadest sector to cover—from Aachen to the southern border of Luxembourg, a distance of 120 miles. Below Luxembourg stood Patton’s Third Army; at Saarbrücken, the front turned east and was the responsibility of Patch’s Seventh Army, which had landed on the French Riviera in August. From just below Strasbourg to Basel, the French First Army held the line.

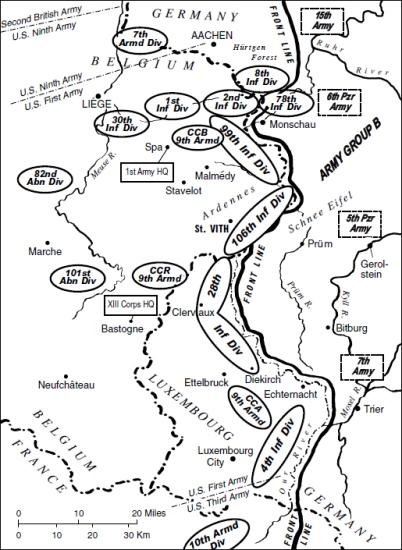

The Western Front, 15 December 1944. (Approximate positions)

Along the Belgian border with Germany was Hodges’s First Army—the veteran 1st, 2nd, 29th, and 30th Infantry Divisions, plus the 2nd Armored Division—all of which had seen months of heavy fighting in and around Aachen and the Hürgten Forest. On their right flank, from Monschau south, were spread the 99th, the 106th, and the badly stretched-out 28th Infantry Divisions.* To the rear of the 28th were the 101st Airborne Division and Combat Command R from the 9th Armored Division.

Lieutenant General Alexander Patch, commander of the U.S. Seventh Army. (Courtesy National Archives)

Below the 28th was the 4th Infantry Division, which had landed at Utah Beach on 6 June 1944 and battled its way across France and Belgium. It had been in the area since September.

It was decided that Montgomery would send his forces in an all-out thrust toward the Rhine north of the Ruhr; Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army would be attached to the British force. Farther south, as part of a one-two punch, Eisenhower would send Lieutenant General George S. Patton’s Third Army, in line south of Luxembourg, racing toward Frankfurt-am-Main. Supporting these attacks would be strong offensive action along the Saar front by Lieutenant General Jacob Devers’s Sixth Army Group, with Patch’s Seventh Army hitting the enemy in Alsace-Lorraine and the Saverne Gap.

Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges’s First Army, consisting of the V, VII, and VIII Corps, would also play a major role in the coming fight; the VII Corps, commanded by Major General J. Lawton Collins, would spearhead the First Army’s offensive and head for Cologne. Major General Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps, comprised of the 8th, 78th, 99th Infantry Divisions,* along with two armored combat commands and a cavalry group, would follow up and exploit any VII Corps successes. To take part in the V Corps offensive, the 2nd Infantry Division was pulled out of its positions east of St. Vith and trucked northward to the vicinity of Dom Butgenbach. The date of 13 December was set as D-day for the start of the offensive.

Major General Troy H. Middleton’s VIII Corps, on the First Army’s right, or southern, flank, had no immediate role in the offensive operations, but would be ready to follow up Allied gains. The VIII Corps would remain in place in the St. Vith sector, between Losheim and Eppeldorf. In reality, the units were in no shape to fight. Two of the infantry divisions—the 4th and 28th—were worn out and, added to Middleton’s corps, were two new, untested divisions: the 99th (which had arrived on the front lines on 9 November) and the 106th.3

Although a veteran of World War I, the 106th’s commanding general, fiftytwo-year-old Major General Alan Jones, a stocky man with a Clark Gable mustache, had never led a unit of any size in combat, let alone a 14,253-man infantry division. Most of his officers, non-coms, and enlisted men were equally green.

Generals Eisenhower and Bradley had earlier decided that the thickly wooded hills in the vicinity of St. Vith would be the perfect place for the new divisions—which had still been training back in the States during the heavy fighting of the summer and fall—to get a taste for living near the front, hearing the occasional distant rumble of artillery fire, and acting as reserves. As the seasoned divisions that had been slugging their way across the Continent since June 1944 became depleted on the difficult march toward Berlin, these fresh units, it was felt, could be quickly brought to the front.

Through no fault of its own, the 106th was about as ill-prepared for combat as any division America ever put into the field. From September to December 1943, 2,756 enlisted men were pulled out of the 106th at Camp Atterbury and either sent overseas as replacements or transferred to divisions that had been alerted for overseas movement. That was just the beginning; from activation to departure for its port of embarkation, the 106th lost a total of 12,442 men— more than eighty percent of its total. The official history of the Army Ground Forces notes, “The withdrawals were often made in driblets, aggravating the disruption of training. For example, there were fourteen separate withdrawals, involving from 25 to 2,125 men at a time.”4

Bringing the division back up to its full Table of Authorization complement was a flood of ASTP students, fresh from their college classes—as well as the rookies from the infantry replacement centers at places such as Camp Wheeler, Georgia—whose military training was minimal at best.

There were other problems, too. One historian noted, “Unlike Regular Army and National Guard divisions, [the 106th] had no distinctive history or achievements, unit pride, or connection with any particular state or region.”5

Once it arrived at the front, the 106th had not had time to acclimate itself to its new positions. While the 2nd Infantry Division, which the 106th replaced, had earlier plotted out preregistered artillery concentrations to its front, and established liaison with the 14th Mechanized Cavalry Group to its north, the 106th had yet to adequately carry out either of these two essential tasks. The officers of the 106th may have thought that, as new arrivals at the front, they would be given time to get their feet wet before anyone expected them to engage in any “real” soldiering. And they may also not have realized that the division, in its positions in the Schnee Eifel, represented a deep penetration into German territory.6

Besides unknowingly taking up positions in a salient, being deployed thinly across an extended front, having inadequate artillery cover, having little liaison with adjoining units, having not even a day of combat experience, and not having “distinctive history or achievements, unit pride, or connection with any particular state or region,” the 106th was also extremely young. One member of the division noted that the 106th “was the youngest division, with an average age of twenty-two.”7

The situation was ripe for disaster.

The American high command saw no reason to expect a German counter-thrust of any great magnitude in the Ardennes. Intelligence reports indicated no major enemy buildup or unusual “chatter” in communications that might suggest that the Germans were planning anything big. Even ULTRA, the system that had broken the German ENIGMA codes and was reading the high command’s messages almost as quickly as they could be sent, deciphered nothing conclusive. Just as the Allies had hoodwinked the Germans about the Normandy invasion, the Germans had devised a deception plan to convince the Allies that Germany was going to stay strictly on the defensive; they made sure that the Allies received this carefully planted information.8*

The middle of December saw Americans back home getting ready for their fourth Christmas of the war. Shoppers stormed New York’s brightly decorated avenues hoping to find just the right last-minute gift at Macy’s or Gimbel’s or Wanamaker’s or Lord and Taylor; gifts for their servicemen overseas had been mailed many weeks earlier.

To help Americans take their minds off the war, Hollywood offered Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet and Judy Garland in Meet Me in St. Louis. But films with a military theme also abounded: Moss Hart’s Winged Victory; Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo with heartthrob Van Johnson; as well as Since You Went Away, Hollywood Canteen, and Doughgirls. Some theaters specialized in nothing but newsreels.

In New York, Broadway staged such hits as One Touch of Venus, I Remember Mama, Life with Father, A Bell for Adano, and Soldier’s Wife; and Miracle of the Warsaw Ghetto played at the New Jewish Folk Theater.

Inside Radio City Music Hall, which budding architect Gerald Daub admired so much, the Rockettes were going through their annual high-kicking holiday show. Gallagher’s Steak House on 52nd Street was giving away a free dinner with the purchase of a hundred-dollar war bond. Even the stockbrokers could smile; on 14 December, the Dow Jones 30 Industrials closed at 151 points.

Somehow, though, with the war dragging on, there was a hollowness to the holiday season. Each day, the New York Times published long listings of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut war dead, divided under the headings of “Army,” “Navy,” “Marines,” “Air Corps,” “Coast Guard,” and “Merchant Marines.” Sometimes the listings ran to a full page. Frequently, photographs of prominent area servicemen killed or missing in action also appeared. Wedged in as it was between the cheery Christmas ads and the sports pages, the death toll was a grim and graphic reminder of the cost of liberty.

On Friday, 15 December, however, the New York Times was full of favorable war reports. The big news was the bombing by the B-29s of Curtis LeMay’s Twentieth Bomber Command, based in India, against Japanese targets in Bangkok, Thailand, and Rangoon, Burma, with “excellent results.” Other air assaults against the Japanese home islands and targets in China were also noted as being “successful.”

In southeastern France, Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army was reported to have gained four miles along a thirty-five-mile front. A war correspondent, writing from Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in Paris, noted that Patch’s army had “smashed northward through the snowy Vosges Mountains within seven miles of the Wissembourg Gap today [December 14] and Marauders [B-26 medium bombers] of the First Tactical Air Force hammered the Siegfried Line defenses . . . in Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower’s bid to break the German defenses at a comparatively weak point and reopen the war of movement in the west.” A map helped readers visualize the situation.

Farther north, Courtney Hodges’s First Army had, after a month of vicious fighting in the gloomy Hürtgen Forest following the battle for Aachen, finally resumed its push toward Bonn and the Rhine. Things were looking up; perhaps the war would, as some had predicted, be over, if not by Christmas, then surely early in the new year.9

While it appeared that the war was being prosecuted to a successful conclusion, the nation as a whole could turn its worries to another pressing concern: the state of the president’s health. Having just waged another knockdown, drag-out presidential campaign and defeated New York governor Thomas Dewey, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the old campaigner and consummate politician, was weary. In photos and newsreels he looked worn and haggard, with darkened circles beneath his eyes; and, indeed, his health was flagging. But FDR could still grin that famous grin and whip off a quip that would have everyone except Republicans laughing. For most Americans, Roosevelt had been like a father figure; in fact, for many, the man now in his eleventh year in the White House was the only president they could remember. Many were privately concerned that Roosevelt might not live to celebrate the victory and enjoy a world of peace that he had done so much to bring about.10

On the night of 11 December 1944, a number of high-ranking German generals were summoned to Feldmarschal Gerd von Rundstedt’s headquarters in a castle at Langenhain-Ziegenberg, a small town about twenty miles north of Frankfurt-am-Main. At the headquarters, they were told to leave their briefcases and pistols behind, and were directed to board a gray-painted Wehrmacht bus.

Puzzled, the generals nevertheless complied. For half an hour, the officers were driven through the dark, snow-covered landscape, through the narrow, winding streets of nearby Ober Mörlen, then through open countryside, making one turn after another until they had lost all sense of direction. Only then did the bus deposit them at their secret destination: the Führer’s underground forward headquarters, known as the Adlerhorst, in the resort city of Bad Nauheim.

“Most of the visitors,” noted the historian Hugh Cole, “seem to have been more impressed by the Führer’s obvious physical deterioration and the grim mien of the SS guards than by Hitler’s rambling recital of his deeds for Germany which constituted this last ‘briefing.’”11

The Führer began his long-winded historical discourse:

Gentlemen! A fight like the struggle in which we find ourselves right now, which is being fought with such unlimited bitterness, obviously has different aims than the quarrels of the 17th or 18th Centuries, which might have concerned minor inheritances or royal dynastic conflicts. People and nations don’t start a long war of life and death without deeper reasons. One can’t deny that the German nation, in terms of size and value, has (earned the claim) in central Europe to become the leader of the European continent. . . .12

Eventually, Hitler got around to the reason why he had summoned them to the Adlerhorst: In four days, the Germany army would launch the biggest offensive since the invasion of the Soviet Union.

Stunned, the generals could not believe their ears. Many privately believed that the Führer had, long ago, lost all touch with reality, and this news certainly confirmed their beliefs. They did their best to change Hitler’s mind, pointing out that their formations were much too weak, the Allies were much too strong, and the chances for victory were nonexistent.

But Hitler had heard this type of defeatist talk from his generals before; he would not be moved. The operation would go ahead as planned—whether they liked it or not. After listening to the details of the scheme, the reluctant generals clicked their heels, gave their leader the Nazi salute, shouted “Heil Hitler,” climbed back into the bus, and began trying to figure out how they could pull off such a massive operation in just four days.13

As early as September 1944, when the American and British drive began to lose steam along the Westwall, Hitler had begun to concoct a plan to throw everything he had at the Americans in an attack so violent it would rival Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, in everything except scale.

Launched at the height of Germany’s military might in July 1941, Barbarossa had involved seven armies, four panzer groups, 150 infantry, panzer, and motorized divisions, three million men, 3,580 armored fighting vehicles, over 7,000 guns, 1,830 aircraft, and 750,000 horses.14 The resources now available for Operation Wacht-am-Rhein were a mere fraction of the Barbarossa force: three armies with thirteen infantry and seven panzer divisions (plus an additional five infantry divisions in OKW [Oberkommando der Wehrmacht—German Army High Command] reserve on alert or en route to the front), 290,000 men, 2,617 artillery pieces and rocket launchers, 1,038 tanks and self-propelled guns, a handful of aircraft. But perhaps it would be enough; only eighty thousand Americans held the seventy-five-mile line between Monschau and Luxembourg City. And the 99th and the 106th Divisions, occupying the schwerpunkt—the point of attack—in front of St. Vith, Belgium, were too inexperienced to put up much of a fight.

The five infantry and four SS panzer divisions of the Sixth Panzer Army, under SS-Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich, would strike Major General Leonard T. Gerow’s V Corps lines between Aachen and Monschau. Dietrich’s army consisted of over 140,000 men, 642 tanks and self-propelled assault guns, and 1,025 pieces of artillery. Spearheading the attack was SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper’s Kampfgruppe Peiper, a unit that would soon earn eternal infamy for its actions near the Belgian village of Malmédy.

To the south, General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger’s Seventh Army, the weakest of Hitler’s attacking force, would hit Major General Troy H. Middleton’s extended VIII Corps’s line along the German-Luxembourg border. Still, the unmotorized Seventh Army had some 60,000 men and 629 artillery pieces and rocket launchers, a formidable force by any calculation. Fortunately for Brandenberger, the Americans facing him—one regiment each from the 4th and 28th Infantry Divisions and a combat command from the 9th Armored Division—were also regarded as weak.

The center thrust would send General der Panzertruppen Hasso-Eccard von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army crashing toward Bastogne and into the unsuspecting ranks of the U.S. 28th, 99th, and 106th Divisions. Von Manteuffel’s force consisted of four infantry and three panzer divisions (90,000 men), 396 tanks and assault guns, and 963 artillery pieces and rocket launchers.

In addition, a thousand parachutists of a provisional Fallschirmjäger battalion would be dropped behind American lines in the early morning hours of 17 December near the Mont Rigi crossroads on the highway from Eupen to Malmédy in Operation Stösser, Germany’s last airborne operation. The commander of the parachute operation, Baron Oberst Frederich-August von der Heydte, inquired about the composition of the American reserve forces his paratroopers might encounter and was angrily told by his superior, Sepp Dietrich, “I am not a prophet! You will learn earlier than I what forces the Americans will use against you. Besides, behind their lines there are only Jewish hoodlums and bank managers!”

As an extra surprise, a thousand English-speaking Germans, dressed in American uniforms, driving captured American vehicles, and commanded by the brilliant commando SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny, would be employed in Operation Greif to sow confusion and disinformation behind the lines. Additionally, Skorzeny’s men were to dash ahead of the panzer columns and seize at least two Meuse bridges. It seemed that Hitler had thought of everything.15

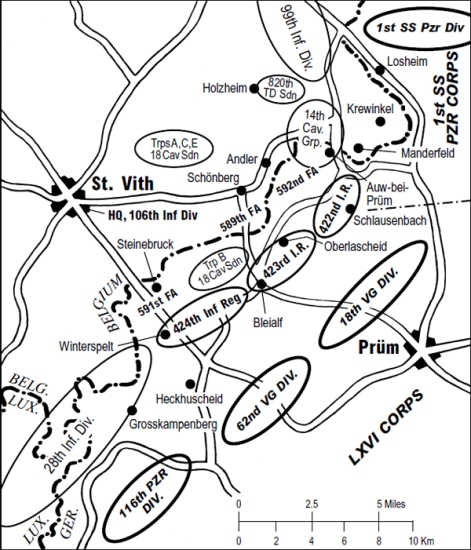

Approximate positions of units of the 106th Infantry Division, adjoining, and enemy units, 15 December 1944.

Although it appeared formidable on paper, the German force was something of a paper tiger. According to Hugh Cole,

In December 1944, Germany was fighting a “poor man’s war” on the ground as in the air. This must be remembered when assessing the actual military potential of the divisions arrayed for the western of fensive. Motor transport was in sorry shape; the best-equipped divisions had about 80 percent of their vehicular tables of equipment, but many had only half the amount specified in the tables. . . . Spare parts, a necessity in rough terrain and poor weather, hardly existed. There was only a handful of prime movers and heavy tank retrievers. Signal equipment was antiquated, worn-out, and sparse. . . . Antitank guns were scarce, the heavy losses in this weapon sustained in the summer and autumn disasters having never been made good. The German infantryman would have to defend himself against the enemy tank with bravery and the bazooka. . . .

Adding to the attackers’ woes, ammunition stocks were dangerously low and there was insufficient fuel to allow the Germans to reach their main objective, Antwerp. Many of the supply wagons and artillery pieces were pulled by horses.16

But strange things happen in war; victory does not always go to the best trained or the best equipped. Hitler gambled that German desperation, surprise, and audacity would be enough.

*Brigadier General James Wharton’s 28th Infantry Division (Pennsylvania National Guard) had arrived in Normandy on 22 July 1944 and got its first taste of combat in the hedgerows around St.-Lô. Wharton was killed on 12 August; Norman D. Cota replaced him. The division paraded through liberated Paris on 29 August, and then saw considerable fighting during its drive across France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Hürtgen Forest. It suffered 5,000 casualties in four months. (Stanton, pp. 104–106)

*The 78th had arrived in theater in late November and reached the front lines on 1 December; the 99th landed in France on 3 November and was at the front by the ninth. (Stanton, pp. 145–146; and 175)

*To avoid tipping their hand, all communications regarding the upcoming German offensive was conducted either in person or via couriers. (Parker, pp. 39–40; and MacDonald, A Time for Trumpets, p. 40)