6

CAUGHT IN A NORTH WIND

IN THE SNOWY hills of Alsace-Lorraine, several hundred miles south of where the Battle of the Bulge was still raging, the curtain was about to rise on the second, and final, act of Hitler’s drama to save the Reich.

After landing on the French Riviera on 15 August 1944 in an operation codenamed Dragoon, the divisions of Major General Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army began fighting their way northward. The first few weeks went relatively smoothly, with American and Free French divisions chasing General Friedrich Wiese’s disorganized Nineteenth Army up the Rhône River valley; at only a few, well-chosen places did the Germans make a stand and offer serious resistance.

As the Allied drive neared the French–German border in September 1944, German opposition became more determined. The Germans, after all, were now fighting with their backs against their borders and were doing everything within their power to keep the enemy out. By October, the fighting in Alsace-Lorraine had settled into a war of attrition, which, little by little, the Allies were winning.

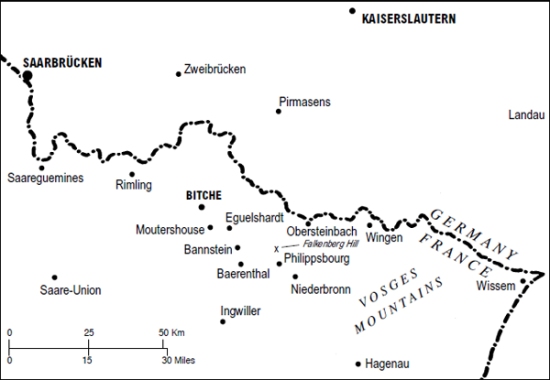

Alsace-Lorraine region.

Here, two new American infantry divisions, the 100th and the 103rd, would see their first combat. Spirits were high. In the official account of the campaign, the authors wrote, “For the 100th, or Century, Division, going into combat for the first time, the prospects seemed less than dismal. The new troops were both nervous and excited, anxious about what the future attack would bring, yet more eager than the veteran soldiers [of the 3rd, 36th, and 45th Divisions, which had been in combat for many months] to show what they could do.” The 100th and 103rd Divisions would soon be followed by another, the 42nd.1

Private First Class Gerald Daub recalled that, upon landing, his outfit—Company F, 397th Regiment, 100th Infantry Division—was immediately ordered north. “We basically raced up the Rhône Valley until we got to about Baccarat,”* Daub said, “where the German army that we were chasing had prepared positions to the south of the Vosges Mountains. I assumed that they felt that the Seventh Army probably would not be able to penetrate the Vosges, because I don’t believe any army had penetrated there before. We were in very mountainous terrain. It was well-treed with evergreens and was very snowy at that time.”

Four members of a machine-gun squad from Company H, 398th Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, prepare to move out near the Maginot Line, December 1944. (Courtesy National Archives)

On 12 November 1944, Daub’s life nearly ended when he was hit in the neck by a sniper’s rifle bullet. “The sniper who shot me was about fifty yards away. He was basically aiming at the middle of my forehead. I saw him just about the same time that he saw me, so I fell to the ground and turned my head as I put the rifle stock up to my shoulder to fire. Probably the movement of my head made him miss my forehead but left my shoulder exposed, which was a little better. We both fired simultaneously; I don’t know what happened to him. I was hit at the base of my neck and the bullet went down my back and out. Luckily, it didn’t strike anything vital.”

Daub lay bleeding in the snow for most of that day because his company was engaged in a heavy firefight and medics were unable to reach him. Help eventually came, and Daub was evacuated to an aid station. From there, he went by jeep, along with a badly wounded German, to a station hospital in Épinal. “I was there two or three weeks; the wound was not that bad. At the time, though, the doctors thought that I was badly wounded, so the Army sent a telegram to my family telling them that I was severely wounded.”

GIs of the 398th Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, move down a wooded lane in Alsace-Lorraine, 17 November 1944. (Courtesy U.S. Army Military History Institute)

After recuperating, Daub was marked “fit for duty” and given the choice of either returning to his old unit or being sent to a replacement depot where he would be assigned to whatever unit needed a warm body. “Well, I was young and foolish. If I had said that I wanted to go to the replacement depot, I probably would have been there for a week or two before being reassigned. But I told them I wanted to go back to the guys I know. So I loaded up my gear and jumped into the back of a truck and, in about an hour, I was back at my battalion headquarters and marched out to where my company was. Everybody was happy to see me, including my buddy, Bob Rudnick. This was in early December—after Thanksgiving and before Christmas.”2

During his absence, Daub’s unit had been moved farther north to Rimling, a crossroads town just south of the German border, east of Sarreguemines. It was an area the Germans wanted very much to control.

In mid-December 1944, Lieutenant General Jacob Devers’s Sixth Army Group had eighteen divisions on the line—two armored and six infantry divisions in Alexander Patch’s Seventh U.S. Army, plus three armored and seven infantry in General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny’s First French Army. Opposing them was the newly created Armeegruppe Oberrhein’s forces: Generalleutnant Siegfried Rasp’s Nineteenth Army* and General Max Simon’s XIII SS Korps. As the Germans’ Ardennes counteroffensive began to bog down, and Patton’s Third Army had been pulled out of their positions and trucked north to hit the German salient, thereby relieving the pressure on Bastogne, Hitler saw the Americans in Alsace-Lorraine falling into the trap he had already set for them.2

Hitler and von Rundstedt’s staff in OB West headquarters at Langenhain-Ziegenberg worked out plans for a large-scale attack by Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz’s Army Group G that would slam into Allied lines north of Strasbourg, split Patch’s Seventh Army, retake Strasbourg, and clear the enemy out of Alsace. Once it was successful, the drive would turn north and strike Patton’s army from the rear, thus reducing the pressure on the Wacht-am-Rhein salient. The assault was scheduled for New Year’s Eve. Daub and the thousands of other Americans on the front lines in Alsace-Lorraine were about to be hit by the white-hot blast of a north wind—Operation Nordwind.

Unlike Operation Wacht-am-Rhein, Nordwind did not come as a complete surprise to the Allies. Intelligence reports had noted the buildup of German units in the vicinity of Saarbrücken, and Eisenhower correctly surmised that the enemy was preparing to launch an attack against Devers’s forces. Plans were swiftly made to go over onto the defensive. With Patton’s army now out of the line, Patch’s six infantry divisions, covering 126 miles, were stretched to the breaking point. Patch directed Major General Wade Haislip’s XV Corps—consisting of the 44th, 100th, and 103rd Divisions—to cover thirty-five miles of front to the west of the Vosges; Major General Edward H. “Ted” Brooks’s VI Corps would man the front to the east. The infantry regiments of three divisions—the 42nd, 63rd, and 70th—were rushed up from the south and turned into task forces to plug the numerous gaps in the Seventh Army’s lines.3

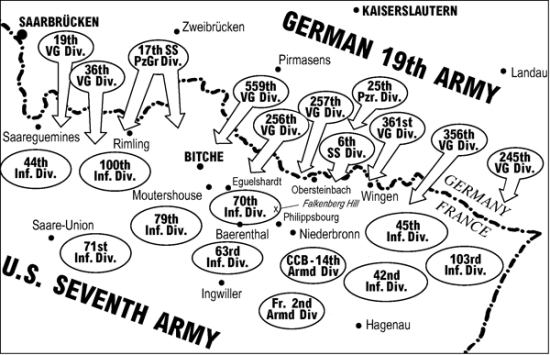

Operation Nordwind. (Approximate positions)

Private First Class Morton Brooks, a member of Company C, 242nd Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division, remembered that it was 8 December 1944 when his “Rainbow Division” (so called because of the rainbow patch they wore on their left sleeve) landed in Marseilles and formed into a task force commanded by Assistant Division Commander Brigadier General Henning Linden. Task Force Linden quickly headed north and relieved the 36th Infantry Division (Texas National Guard) along a thirty-mile front in Alsace-Lorraine.

On the move, Brooks related that his outfit did not encounter much resistance. “We had a Free French unit on the right of us, and I was running a liaison with them for a while. The fighting was just sporadic and it wasn’t too serious. You might get strafed or you might see some activity, but nothing too significant.”4

Late on 31 December 1944, the situation changed dramatically. All hell, as the saying goes, began to break loose. Two thousand men of the 37th SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment of the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division, supported by salvos of well-placed artillery rounds, charged through the darkness with suicidal abandon into the lines of the 100th Division’s 397th Regiment, which refused to break. At Rimling, however, elements of Simon’s XIII SS Korps did manage to penetrate about two miles into the seam between the 44th and 100th Divisions, but were pinched off and the threat was eliminated.5

A member of Company I, 242nd Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division, prepares a belt of 30-caliber machine-gun ammunition outside his improvised log-and-dirt bunker, January 1945, during Operation Nordwind. (Courtesy National Archives)

Before the Germans were thrown back, however, Gerald Daub’s battalion was in Rimling and was attacked by the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division. “We had no tank support at that time and, apparently, we were very anxious for this crossroads. We were so vulnerable that they were able to attack us from both the front and the rear,” said Daub.

A Sherman tank of the 781st Tank Battalion stands guard on the outskirts of Wingen, France, during the Germans’ Operation Nordwind. The GI helmet, destroyed jeep, and burning truck in the distance attest to the heavy fighting. (Courtesy National Archives)

The Germans had no air power to speak of and were loath to leave their tanks exposed during the day. When a panzer broke down, they pulled it out and would leave their infantry behind to hold the terrain. Daub said, “We would go from house to house and roust out their infantrymen and either shoot them or, more often than not, they would surrender. That went on for several days.”

Daub was sent on a patrol with a scout from the first squad, a soldier by the name of Howard Hunter. The two were ordered to go up to the northern edge of Rimling and observe any German movement into the town. “Our instructions were to report back to company headquarters and tell them what was coming that particular evening,” Daub said. “We picked a very nice house that commanded a bend in the road where we could see right up to the top of the little hill the town was on.”

Toward evening, a German armored reconnaissance unit with several tanks approached the town. “The first tank had infantrymen all around it, dipping and dodging and coming down the street, heading toward the house Howard and I were in. Howard and I fired at them and they fired at us. As we stood there, the tank—we were on the second floor of the house—rumbled right up to the house and put the muzzle of the gun in the window where we were standing. I sort of touched the muzzle as I turned around to talk to Howard. If I were smarter, I might have dropped a hand grenade down the muzzle, or maybe it would have been dumber—I don’t know.”

Daub and Hunter bolted down the stairs and dashed out of the house. “That part of the town was on a hillside, so it was terraced, and we jumped right into a group of German soldiers. Howard swung his rifle butt at the nearest German and the two of us ran into the first house that we came to. It was my thought, and I’m sure his, too, that we would just go through the house and out the back and head back to our company headquarters.”

Unfortunately for Daub and Hunter, the farmer who owned the house had done a very good job of boarding up all the windows and doors, and once the two got inside, there was no way out. “We went to the furthest place in the house, which was the kitchen, and we heard the Germans coming in after us. There had been a lot of shelling in town and so there was a lot of grit and sand on the floor; we could hear their boots. It was dark and the house was boarded up, so we couldn’t really see. As they came down the hall toward us, they were throwing hand grenades into each room. Finally, they came to our room.”

The two Yanks had turned over a very heavy wooden kitchen table and were taking cover behind it. “They tossed the grenade in and we got down behind the table, and the table just bounced and nothing really happened to us. Howard said, ‘I think we’d better surrender.’ I recall saying to Howard, ‘Not me, Howard—I’m Jewish.’ So Howard didn’t surrender; he stuck with me.

“They threw another grenade in, and then we heard what we knew was a machine pistol being cocked at the door; that table was not going to resist the bullets. I said to Howard, ‘Howard, discretion is the better part of valor—I think we better surrender.’ So we threw our rifles out onto the floor, and we yelled ‘Kamerad!’ and walked out toward them. They grabbed us and dragged us out the door and searched us. We were prisoners of war.”

Leon Horowitz, photographed in 1943 at the University of Indiana. (Courtesy Leon Horowitz)

The soldiers took Daub and Hunter back to the tank, where a badly wounded German was lying in the street. “They ordered us to pick him up and put him on the tank. It was a Panther tank—a big tank with ridges across the front, and we picked him up and set him up above the ridges, and the tank commander told us to get on the tank. So we got on, and the tank backed up, turned around, and headed out of town.

“As we proceeded along the ridgeline, this wounded German soldier was groaning and screaming for his mother. The screaming stopped and I said to Howard, ‘I think this guy is dead.’ I think the Germans knew it too, because they stopped the tank and ordered us off, and I thought surely they were going to shoot us now.”

The tank commander told the two Americans to take a shovel from the back of the tank and dig a grave for the dead soldier. “The ground was frozen as hard as concrete,” Daub recalled. “At that time of year it was very hard to dig a foxhole—or anything else. The two of us scraped at it and chipped at it and they finally said, ‘That’s enough,’ so we just rolled his body into it and threw some snow on top of it. We didn’t know what was going to happen next, but they ordered us back onto the tank and drove off to where they were camped, just on the other side of the border in a little farmhouse. They put us in the barn and interrogated us.” The next day, the Germans brought in the rest of the company, along with Daub’s friend, Bob Rudnick.6

Leon Horowitz, a soldier from Brooklyn and another member of Daub’s Company F, 397th Infantry Regiment, 100th Infantry Division, was also taken prisoner at Rimling. He quickly faced a moral dilemma that confronted all of the soldiers who were Jewish: “When I was captured, one of my soldier mates advised me to throw away my dogtags. In those days, your religion was imprinted on your dogtags so that, if you were killed in action, they would know what kind of burial service to give you. I threw away my dogtags shortly after I was captured. In retrospect, the Germans would have quickly suspected that anyone who didn’t have dogtags was Jewish.”7

The 42nd Division was not spared any of the fighting. Morton Brooks, Company C, 242nd Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division, recalled, “We were moving toward Germany and I guess the Germans were making an attempt to recapture Strasbourg, and they hit us with an overwhelming force.”8

The division fought back hard. A citation his unit was later awarded hinted at the ferocity of the fighting:

The First Battalion [of the 242nd Infantry Regiment, 42nd Infantry Division] was occupying a front of four thousand yards when it was attacked by three regiments from the 21st and 25th German Panzer Divisions supported by heavy armor and artillery. Ordered to hold this position at all costs, the battalion withstood repeated onslaughts of enemy flame-throwing tanks, self-propelled guns, and infantry. Time after time, small detachments of the battalion remained steadfast after their positions had been overrun by hostile tanks in order to stop the foot troops that followed. Cooks, clerks, mail orderlies and supply personnel fought side by side with riflemen, completely disregarding their personal safety. In spite of loss of over five hundred officers and men, the battalion tenaciously held its position in the face of overwhelming odds for more than fifty-two hours until relieved, exacting a heavy toll of men and equipment from the enemy. The courage and devotion shown by the members of the First Battalion, 242nd Infantry Regiment, are worthy of emulation and exemplifies the highest traditions of the Army of the United States.9

Two soldiers of the 100th Infantry Division’s 397th Regiment stand watch with their water-cooled .30-caliber machine-gun in a foxhole near Rimling, France, January 1945. Note one soldier is wearing a white parka and the other a white helmet cover to help them blend in with the snowy terrain. (Courtesy National Archives)

Brooks said that he was lucky to be alive. “I was in a forward foxhole. Part of our company—a couple of our squads and the rest of the fellas who were in the town of Hatton—really were blasted away. Most of the company was wiped out and so, in a way, I was fortunate that they had overrun our positions during the night. We were really cut off. Our own artillery was beginning to fall on us, and our phone lines were cut, so I was asked to reconnect the phone line. I took off and was following the line. I got back to a bunker and found some of our fellows cowering in there; they had experienced a lot of shelling during the night.”

While Brooks and the other soldiers were trying to determine what they were going to do, a sergeant looked out and saw a Tiger tank coming up the road. “He said we’ve got to surrender, which I didn’t want to do, but that was pretty much it. He was concerned, and rightly so, that they would just put the muzzle of the tank’s gun into the entry of the bunker and we would be killed.”

Brooks noted that the Germans came out of the woods and set up a machine-gun across from his bunker, then ordered the Americans to come out with their hands up. “We came out and were kept in a trench until their units moved ahead. Then we were marched back to a farmhouse. All of us who were captured at that point—about fifteen or twenty of us—were held there for a couple of days. They interrogated some of us and got our names, rank and serial numbers, and they tried to get some more.”10

Like the 106th Infantry Division that had been hard hit near St. Vith, the 70th had been raided during its training for thousands of partially trained soldiers to replace battle casualties in overseas divisions. Like the other units in Alsace-Lorraine at the end of 1944, the 275th Regiment of the 70th Division was on the line in the vicinity of Philippsbourg, Schwarzenberg, and Falkenberg Ridge as part of Task Force Herren. As the 70th was moving to attack on New Year’s Eve, it ran headlong into the German 256th, 257th, and 361st Volksgrenadier Divisions launching their own part of Operation Nordwind. The fierce fighting in the snowy hills would soon be known as the “Battle of the Bitche Salient.”11

Company B, 275th Regiment, 70th Infantry Division, was moving forward near the Falkenberg Ridge when it came under intense enemy fire. Private First Class Tony Acevedo, a medic with Company B, had been on a patrol and was about to return to Philippsbourg, when the patrol was told that Philippsbourg was occupied by the Germans. “So we were to head toward a hill called Falkenberg Hill. I got word that the company commander, Captain William Schmidt, was seriously wounded inside a cave there.”

The company was ambushed and Acevedo recalled that some of the troops around him began to panic during the ambush. “As a medic,” he said, “I encountered fellas who were shell-shocked and scared, and some who even wanted me to baptize them.”

When Acevedo reached Falkenberg Ridge, he saw that another medic had been killed while he was taking care of Captain Schmidt. “I continued to bandage Schmidt’s wounds. We’re up to our waists in snow and the Germans are surrounding us with tanks. We had already been bombarded by our own planes to keep from being captured, but the bombs were getting too close.”12

Norman Fellman, also of Company B, has his own memories of the events leading up to the surrender. “Company B was about twelve kilometers outside of Philippsbourg when the ambush occurred. Our battalion was ordered to hold the whole range of hills. One of the hills that we were on was the Falkenberg. Nobody was keeping us much up to date as to what we were doing. We were cut off; we had lost communications and had sent out patrols. The patrols would go out and we never heard from them again; we didn’t know if they got through or not.

“Our captain was wounded the first day we were on that hill. We lost some officers and that was the beginning of our casualties. We had scooped out foxholes as best we could in the rock, and we were pretty much out of ammo. The Germans came around with flame-throwing tanks at the base of the hill. The Germans evidently decided to bypass us initially and had gone around us and were cleaning up when they came back to get us.

“There was an overhang there on the hill—almost like a cave, but not quite. Our wounded were all in that area, back in a corner section. We only had rations enough for one night, and anything that wasn’t eaten after that first night on the hill we pulled for the wounded, which were beginning to build up.” Fellman and his unit were there for nearly a week with no food. Water came from melted ice and snow.

Running low on ammunition, and with no hope of rescue, Fellman noted that his surrounded unit was confronted with three choices—none of them good: “We could freeze to death, we could starve to death, or we could surrender; the decision came down to surrender. We tried to damage our weapons as best we could to make them inoperable, and then we surrendered. I was only in combat itself for a few weeks, from the middle of December to the fourth of January. Then it was all over for me.”13

January. Then it was all over for me.” Tony Acevedo recalled, “The Germans came up and we had to give up. I was forced to take off my boots, which were no good; we were in slush. We were not equipped for the winter. We had to wear several pairs of socks just to be comfortable. So we went down the slope barefooted to where the German trucks were.”14

Before the march to captivity, Fellman noted, Company B was formed up and the wounded were evacuated. “We were then marched to a railhead, a few days’ marching. My first encounter with a rifle butt was while going past a bridge abutment; there was an icicle hanging from it. I was dry and thirsty, so I stepped out of line and grabbed the icicle and got my first introduction to the fact that we weren’t free to do what we pleased anymore.”

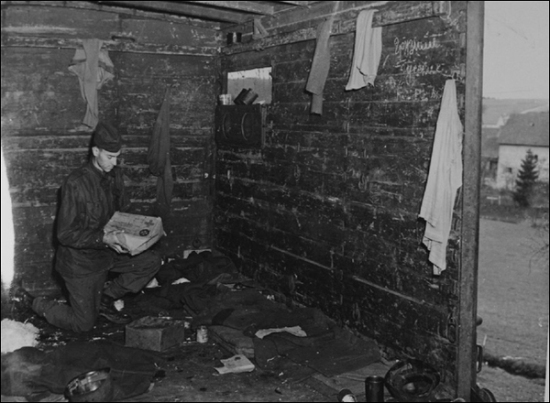

Interior of a boxcar that was used to transport POWs. (Courtesy U.S. Army Military History Institute)

The Americans were taken to a railhead and were packed into boxcars. “They probably had cattle in them at one time, because they weren’t very clean,” Fellman said. “We had between sixty to eighty men to a car. It was freezing. The only guys who had any heat were the ones in the middle. Once the doors closed, they didn’t open; we were in these cars for about four or five days—I don’t remember exactly. If you had to go to the bathroom, you used your helmet—your steel pot—but there was no place to empty it.

“We sat in the railyards in Frankfurt for awhile. We were strafed and there were hits taken, but whether it was our planes or somebody else’s, I don’t know. We lost some guys.”15

Gerald Daub remembered that the group of prisoners he was in was “taken to the nearest rail line, each given a loaf of bread, and put into boxcars with some other Americans that had been captured. The boxcars were locked and wired shut, and we went on about a week’s journey to Frankfurt-on-Main. When we arrived at Frankfurt, it was night, and I think it was the Royal Air Force that bombed the railyards while we were sitting there in the boxcars. One of our officers, Lieutenant Rabinowitz, was killed in the bombing and strafing. He was in a different boxcar; nobody in my boxcar was injured, that I can recall. We went on to Bad Orb.”16

What neither Fellman, Daub, Acevedo, Brooks, nor Horowitz learned until much later was that Operation Nordwind had turned into a complete disaster for the Germans. Although the battle raged throughout the month of January, the Allies held the line and threw the Germans back with heavy losses; total Seventh Army casualties for the battle came in at 14,000 dead, wounded, or missing, while the Germans lost 23,000 men.17

Nordwind was Germany’s last major counteroffensive of the war. But while Germany was fighting to stave off defeat, the Americans captured during Operations Wacht-am-Rhein and Nordwind were soon fighting for their very lives.

Once the train carrying him and several hundred other prisoners reached Bad Orb, Gerald Daub recalled, “We were marched through the town and the local people were very angry. We were marched to this very large prisoner of war camp called Stalag IX-B. The barracks that we were assigned to had a great deal of the 106th Division in it already. We were in a very large stone barrack; there were no beds or bunks—just straw on the floor. I think the building probably was an old stable. At that time, we thought the food and living conditions were pretty bad, but we really didn’t know what was to come.”18

During the in-processing procedures, the Germans seemed inordinately interested in the new prisoners’ religions. Morton Brooks recalled, “When we were processed, they had American soldiers doing the processing and they asked about religion. This was not something we had to provide, but they said, ‘Look, we were told that we had to get it,’ and that was it. I wasn’t going to hide who I was, so I gave it.”19 He had no idea what was in store for those who identified themselves as Jewish.

As more and more prisoners piled into Stalag IX-B, the camp administration became concerned that, unless something was done, the lager would burst at the seams. Late on the night of 27 January 1945, the lid blew off.

Nearly crazed by hunger, two American privates by the names of Sparks and Leondosky decided to raid the camp’s sole source of food. Everyone who was there has some version of what transpired. Martin Hagel, a private first class with Company I, 422nd Regiment, 106th Division, said, “They broke into the prison camp’s kitchen to obtain food. A German guard discovered them in the kitchen and Private Sparks hit this German guard with an ax, splitting his skull open. The German guard was discovered later and his life was saved.”20

James V. Smith noted, “They broke into the kitchen. There was this old guard, probably in his late seventies, and they beat him up and cut him up with a hatchet, of all things. That was a Saturday night. The next morning, when they normally let us out to go to church, they took us outside and lined us up in front of these machine-gun squads. They told us if we didn’t report who did that terrible thing, they were going to start shooting twenty of us at a time.”21

According to Jack Crawford, “The Germans were pretty upset over the incident. They took us outside and lined us up out in the cold for a long period of time. They were trying to find out who did it. A lot of fellows passed out. That was a little nasty.”22

Norman Fellman added, “They marched us out and put us into this quadrangle in whatever condition they found you sleeping in. If you had shoes on, you had shoes; if you didn’t you didn’t. If you had time to grab your coat, you got a coat; if not, you didn’t. We all slept in our clothes; nobody took off anything, so most of us had our overcoats on because the barracks weren’t heated and you did whatever you could to try and keep warm. We were outside in the cold for a little over seven hours. They had machine-guns lined up on us and they said they were going to start taking us down if they didn’t find out who broke into the storeroom. That’s when I noted the chaplain [First Lieutenant Edward J. Hurley], because he came out and they were able to push the offenders out front and turn them over to the Germans. We were finally allowed back into our barracks.”23

Richard Lockhart said the camp commandant wanted to find out who the culprits were. “Nobody came forward, so they announced that they were going to take every tenth man and shoot him unless the culprits admitted their guilt and stepped forward. They set up these machine-guns right in front of us. Apparently, the Protestant and Catholic chaplains negotiated with the German authorities at the camp and said that they would look for the persons responsible. They went through and identified two men who were complicit in the incident, and they admitted it. We were finally allowed to go back to the barracks. None of us got any food whatsoever that day. I don’t know what happened to those two soldiers. From what I have read of other accounts, it is my understanding that they were put into solitary confinement; if they had killed the guard, I think there would have been another consequence.”24

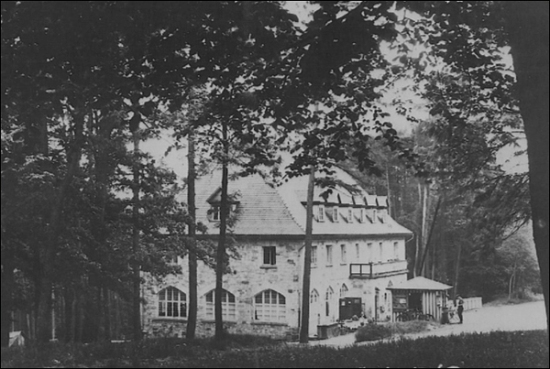

Headquarters building at Stalag IX-B, Bad Orb, Germany. (Courtesy National Archives)

After the attempted murder, camp life settled into a dull routine that was soon upset by the Russian POWs. James V. Smith related, “They let the Russians roam around in the camp. What we called the potato wagon would come through the front gate and come up the hill toward the kitchen; the Russians would run in and grab potatoes or, if it was loaded with bread, they’d grab loaves of bread. The German guards—they were all old people, or they’d been wounded on the Russian front—didn’t stop it.”

To halt the problem, the camp administration formed a company of military policemen from the Americans; Smith, at six feet tall and almost two hundred pounds, was appointed to be one of the MPs. “They took my steel helmet and painted ‘MP’ on it in white lettering,” he recalled. “It was our job to keep order at the kitchen and protect the wagons bringing in food. So that meant a knock-down, drag-out fistfight. We noticed that the Russians were taking any bread and potatoes and whatever to this young Russian colonel and he would decide who got what. We finally realized that he was the one we had to beat the hell out of. Which we did, very easily. That was my job for awhile. We stopped the raiding of the potato wagon.”25

Prisoners continued to be assigned to work details. A new arrival, Private First Class William C. Thompson, from Hialeah, Florida, and a member of Company E, 253rd Regiment, 63rd Infantry Division, who had been captured near Sarreguemines, was sent on a burial detail, but the strenuous work “took more energy in the cold of winter than could be recovered by the extra liter of soup given as pay. The frozen ground had to be pick-axed and lifted out by hand. No thank you! No gravedigging for me!”

Thompson instead was assigned to housekeeping chores—with somewhat amusing results. “I was taken out of the compound to the German officers’ quarters, given a broom, and told to sweep down. The commander’s quarters were sparsely furnished, containing a rough bunk bed, a dressing stand, and a low chest of drawers upon which sat a plate with half of a spiced walnut cake. Next to the cake was a squatty bottle of brandy. The dust began to settle as I set the broom aside and sliced a small piece of cake. It was delicious. So I took another slice. He’d never miss only two small slices.

“I had never drunk strong spirits, but I poured a glass of brandy and chased the cake down. More brandy. More cake. I was reeling. To cover my crime, I began furiously sweeping the floor but found myself drawn again and again to the squatty bottle on the chest. It was soon almost gone and I was drunk as a sailor. I finally had to lie down on the commandant’s freshly made bed. I was rudely shaken awake by an enlisted German guard who was shaking with fright at the sight of a drunken, lice-infested POW sleeping in the captain’s bed after having consumed a cake and most of his fine brandy.

“I soon found myself on the operating end of a bucksaw, cutting logs for firewood. I had difficulty keeping the saw blade taut and was receiving a tonguelashing when I was saved by the flyover of a thousand-plane raid. The sky was filled with contrails, and P-47s weaved back and forth.

“We were all looking up. I told my guard, ‘All is kaput—you’re going to lose.’ He said, ‘When, for God’s sake, when?’”26

Stalag IX-B also held several black American soldiers who had been captured during the two German counteroffensives. As Private First Class Fred G. Koenig, of the 422nd Regiment, 106th Division, remembered, “It was some time in January or February 1945 that a Corporal Schultz, a German guard at IX-B, beat up a colored American soldier. I witnessed this assault. The colored soldier was called ‘Shorty’ and came from Baltimore.” Shorty’s crime was walking past a group of German guards without saluting. Schultz stopped him and said something in German which the American did not understand, so Schultz hit him several times with a bayonet scabbard, knocked him to the ground, and kicked him. “Shorty was a bloody mess,” said Koenig.27

James V. Smith remembered that he was moved out of Barracks 44 and into the MP barracks in front of the kitchen. “There, for their own safety, we had three African-American soldiers. The camp commander suggested that we put them in the MP barracks for their own protection. He said, ‘We’ve got a lot of fanatical idiots.’ Which was an understatement. He was afraid that if we didn’t keep them in there for their protection, some German might do harm to them.”28

Just as the prisoners were beginning to accept their fate at Stalag IX-B and wait out the war in the camp, a startling order came down that would significantly change the lives of hundreds of the American inmates.

*About fifty-five miles west of Strasbourg (sixty-five miles south of Saarbrücken).

*On 15 December 1944, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler had replaced the less-than-enthusiastic Wiese with Rasp. (Clarke and Smith, p. 485)