10

TOTENMARSCH

BEYOND BERGA, SIGNIFICANT military developments were taking place, with the Russians, British, and Americans squeezing Germany on all sides. On Monday, 2 April 1945, American forces reached Stalag IX-B, the mountaintop POW camp at Bad Orb.

The night before liberation, the barracks doors were left unlocked, and the searchlights on the guard towers remained dark. William Thompson said, “We opened the door after dark to find the yard filled with POWs milling around. ‘The guards are gone,’ someone said, ‘at least most of them are.’”

A kindly old guard the prisoners called Schmidt, a farmer in civilian life, entered Thompson’s barrack. “Schmidt said that the staff had fled but he wanted to stay. The war was over for him. We took him and put him back in a far corner. We covered him up in a blanket as he had done so many times for our own sick. He snored like a lion as German tanks and infantry climbed the hill beyond and passed our nervous compound, heading down into Bad Orb. Along about midnight, they roared back up and retreated into the night. From Bad Orb below came a steady sound of tank guns and 105s [howitzers].

“Some time after midnight, the clink, clink, clink of infantry could be heard moving through the woods outside the wire and on the road. It was pitch black. Not a spark of light. We didn’t know whose troops they were but we knew their nerves were on hair-trigger alert and the slightest out-of-place sound would result in a barrage of fire. We returned to our barracks and kept quiet. If we should come under heavy fire, I had planned to crawl across the yard to the latrine. . . . It was the only ready-made foxhole available.

American and British prisoners react with joy as their liberators free them from captivity at Stalag IX-B (Bad Orb), 2 April 1945. (Courtesy National Archives)

“The firefight in Bad Orb continued until dawn. Three Shermans squeaked and clanked up the hill road. They halted just below the crest, listening, turrets turning left and right, then up a little more. Finally, they took the bit and roared up the final stretch to the first entrance gate opposite the beer hall for off-duty guards. BLAM! The first gate went down. BLAM! The second gate flattened under the tank tracks. BLAM! The third gate went down and we were free at last! Damn, those tanks were beautiful in the morning sun. A jeep sped past the lead tank, carrying a colonel chaplain. The driver, unbelievably, was an old acquaintance of mine from Boy Scout days. He drove right past me. Didn’t see me and probably wouldn’t have recognized me if he had. We were scarecrows in dirty uniforms. . . .

“Behind the jeep came three Shermans, loaded down with supplies of delicacies that only tank outfits can carry—live geese-a-honking, live pigs-asquealing, cartons of 10-in-1 rations in case they got hungry in the night—a deli on a half-track.”

The starved men charged the food-laden vehicles and stuffed themselves with everything edible. A Red Cross truck then drove into the compound. Thompson said, “Two hard-working young ladies began handing out real coffee and doughnuts. The rich food reactivated our diarrhea to the extent that the compound began to resemble a duck pen as dozens of POWs were hit with a call so acute they dropped their pants and puddled up in full view of the doughnut wagons. To their everlasting credit, those dedicated ladies never flinched.

“We introduced Schmidt to the officers who were setting up a control unit. We told of his efforts on our behalf. He was paroled that first day and delivered in a jeep to his wife on their still-intact farm. . . . He was a decent man.”1

James V. Smith recalled that the liberators began moving out the prisoners who were the sickest and those who had been wounded. “They moved them out by ambulance for several days. Since I was one of the healthiest ones in the camp, it was about ten days or close to two weeks before I got out. They took me to Fulda, which had been a big German air base. They had a Red Cross tent set up there, and they gave us shaving equipment, toothbrushes, toothpaste—this type of thing.

“Later, we were deloused. We had to throw away all of our old clothes; they were full of lice. On some of the warm days in March, we had been able to take off our shirts and pick the things off, but you never get them all. On the morning after I arrived at the camp in Fulda, a C-47 came in loaded with 55-gallon drums of gasoline. They unloaded the gasoline and then loaded us on the plane and flew us back to France to a place called Camp Lucky Strike [near Le Havre]. After a few days there, they started feeding us a lot of eggnog to try and get us to regain some weight. All of us had lost a tremendous amount of weight. I probably weighed around 210 to 220 pounds when I was captured; when I came out of there, it was probably close to 150.”2

Jack Crawford recalled, “We could see the fire [in Bad Orb] from a distance, and you could hear the gunshots. The Americans came up to the camp on tanks. One of the GIs gave me a can of chicken soup—it was really good.”3

Not wanting the Allies to discover the enormity of their monstrous crimes against the Jews and others, the Nazis were evacuating the concentration camps and death factories. Suddenly, the roads of Germany were crawling with living skeletons in striped uniforms.

The evacuations had begun as early as mid-January 1945, when the death factory of Auschwitz, in Poland, was quickly emptied and its 60,000 surviving inmates forced to march toward Wodzislaw. Anyone who fell behind was killed by the SS guards; over 15,000 never made it to Wodzislaw. Once the survivors reached their destination, they were packed into boxcars and transported to Buchenwald, Dachau, Flossenbürg, Mauthausen, and other camps inside Germany; on 27 January 1945, Soviet troops entered Auschwitz to discover 7,000 deathly ill prisoners and the grim evidence of mass murder.

Throughout January, other camps were evacuated by the Nazis. From dozens of camps came tens of thousands of weakened prisoners, suffering from the wintry conditions and the brutal treatment of their SS guards. For example, some 5,000 prisoners from Stutthof, in northern Poland, were herded into the freezing waters of the Baltic Sea and machine-gunned to death without reason.

In late March and early April, thousands of inmates were evacuated from Buchenwald and its sub-camps. Some evacuees were marched northward, toward Hamburg, while others were taken east, toward Chemnitz and Theresienstadt. The Third Reich had spent many years and expended billions of Reichsmarks to build the camps and use the efficient German railway system to transport millions of people across Europe for the sole purpose of killing them. Now those who had been lucky enough to survive the camps were sent on foot to wander the roads under armed guard in order to keep from falling into the hands of those who might save them.4

On the third of April, the door of their barrack opened and the American prisoners at Berga were rousted out for what they thought would be just another miserable day of hard labor and brutal treatment. But this was to be no ordinary day.

After appell, the prisoners marched—not toward the worksite, but out of town, under the watchful eye of a handful of German guards overseen by Hauptmann Merz and Kommandoführer Metz.5

“When we were captured, the U.S. Army was at Germany’s border,” Gerald Daub recalled. “We felt that we were definitely winning the war and so, after a couple of months had gone by, we knew the American army must have gone on the offensive again, and soon they would be approaching us. But we had no idea how close they were until the Germans marched us out, and then we felt that we were probably marched out of the camp, not to save our lives, but just to get us out of the camp because the Americans were getting close. The American army entered Berga just a few days after we left.”6

When the march southward to Bavaria began, there were 280 Americans who started out; twenty-five of the original 350 had died at Berga or were “shot while escaping”; another twenty-five had been taken to hospitals. Another twenty had escaped from the camp, their whereabouts unknown.7

No one had any idea where the group was going. All anyone knew was that they were heading south. After being confined for so long, the road march should have been a tonic for the men’s spirits. All around were signs of spring: green grass, budding trees, twittering birds, fragrant air, farmers working their fields behind horse-drawn plows. Escape from the meager guard force in this open country seemed possible, yet no one had the strength or will to try. “The Germans had about four or five who watched us—not a large number,” said Morton Brooks. “They really didn’t need a large number.”8

The city of Plauen, through which the POWs marched. (Author photo 2004)

The men were in no shape to make this march, let alone escape. William Shapiro realized, “None of us . . . had any idea how destructive this march would be to our group. All debilitated, exhausted, emaciated, sick, maimed, and cowered soldiers. It was simply walking—no strenuous work in the tunnels, no lifting heavy rail ties, no moving of rail track for eight hours daily. This was a walk at a slow pace, interrupted by a break every hour and one half in order to defecate, urinate, or just sit down along the gutters of the road. Simple!”

But Shapiro added, “We were totally unprepared for the horrors that we would encounter—the profound despair, the inability to continue to take another step forward, the discovery of dead buddies each morning, and the wanton, gross murder along the roads.”9

The straggling line of POWs plodded through the hostile stares of citizens in the bombed-out center of Greiz—an old, baroque city with a castle looming high above the Elster River—then Plauen, then Hof, where ten marchers died. Each day, when the wilting prisoners asked their guards where they were going, the answer was always the same: “To the next town.”

Although the city of Hof, near the Czech border, was only thirty miles from Berga, some of the soldiers could go no farther. Norman Fellman recalled that, near Hof, his infected leg swelled, causing his boot to burst. “During the night, we were in a barn. I tried to get up the next morning but my leg was full of pus; I couldn’t walk, so they found a cart that had an old horse pulling it. This cart was ‘V’ sided—narrow at the bottom and wider on the top. It could probably hold eight or nine people comfortably; they piled twenty-five, thirty guys in it. More than once the guy on the bottom suffocated. So you played Russian roulette everyday as to how they loaded you.”

At some point during the march, the horse pulling the “sick wagon” disappeared; the POWs were drafted to pull and push it—an almost impossible task for men who could barely walk. Fellman said, “There was a fellow that I knew— a guy named Greg. He talked about his brothers and family at home. His head was in my lap; he was disabled somewhere along the line. I don’t know what his problem was, but he’s talking about giving up, that he couldn’t take it anymore. I talked to him for hours, trying to give him all the reasons why he should live— his family needed him and his brothers needed him and so on, and somewhere during that conversation, he passed away. I don’t know how long I talked to him after he was dead.”

Liberation came quickly for Norman Fellman. The column of POWs had become strung out even before the group reached Hof, and he and several comrades “were liberated on the road in the vicinity of Hof by elements of the 90th Division. I was taken to a field hospital and, after a day or so, was flown to Paris to a hospital where I remained for a period of time.”

Fellman was unable to articulate exactly his joy and emotions at finally being liberated: “I don’t know if I could ever explain it, and I don’t know that I could ever make someone else understand it. You almost have to be in the similar situation. It was overwhelming, it really was. Some of us let go of all of our restraints, messed ourselves up. All the restraints that we had in trying to stay alive and to be able to move, to be able to watch out for yourself, all gave way. We had no idea how bad we looked until we saw [the liberators’] eyes when they saw us. We felt like we were lepers. They certainly didn’t try to make us feel that way. But we were about as close to being skeletons as we could be and not be one.”10

The rest of the group, perhaps stronger and able to walk at a faster pace, was forced to keep marching farther from the liberating arms of the 90th Division. Norman Martin recalled the death of a prisoner named Israel Cohen while on the march: “Private Cohen had considerable difficulty in maintaining the pace of the rest of the men. About the seventh of April, he collapsed from exhaustion. . . . He was put in a manure wagon, which was used as a sick wagon. He was the first one in the wagon and, during the day, more men began to fall out from exhaustion and illness. Private Cohen was on the bottom of the cart and as each man would collapse, they would be thrown on top of Private Cohen. Toward the end of the day, there were many men piled on top of Private Cohen. When I saw him, he was dead, and from the position in which he was lying, he must have died from suffocation from all the men being placed on top of him. . . . His face was a picture of agony, and from the position of his body, he looked as if he had been struggling to get air. . . . We protested to Metz that the conditions were in violation of the Geneva Conference and he told us that he was the only Geneva Conference available.”11

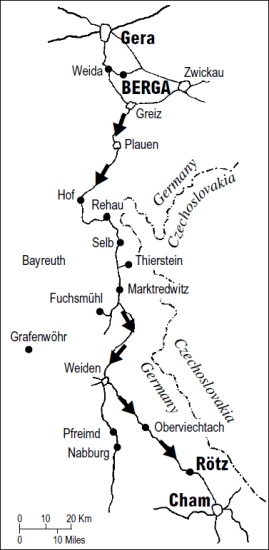

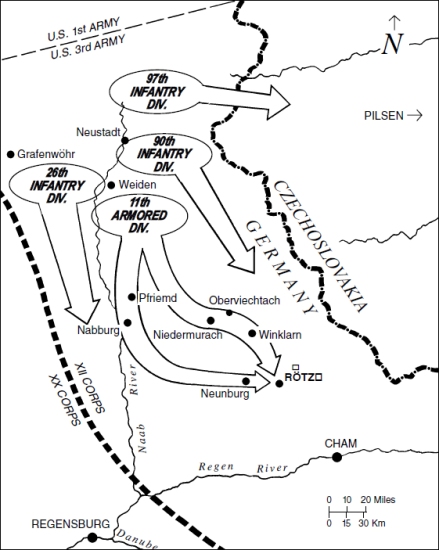

Route of the “Death March”— from Berga to Rötz— 3–23 April 1945.

While on the march, Gerald Daub handed Joe Mark a small bag of potatoes he had picked up somewhere along the way. “He asked me to take it,” Mark said, “because he couldn’t carry it anymore. I was not a leader, but I was twenty-three years old and a senior member, as opposed to Gerry and most of the others, who were eighteen. I took the potatoes and hung the bag on the wagon loaded with the very sick so that, later, we had access to the potatoes.

“We would stop in barns at night for rest. One guy killed a chicken. We couldn’t make a fire, so I ate the white meat raw but, even starving, I couldn’t swallow the dark meat.”12

On 9 April, south of Hof, Peter Iosso said the group “reached a town that had somehow become free of federal control. Although we didn’t understand the words, body language told us that the Burgomeister was chewing out the Kommandoführer [Metz], probably about us. Fifty of our sickest were taken to a hospital; the rest of us stayed in a clean barn. For the two or three days we stayed there; they gave us slices from freshly baked family loaves and boiled potatoes.”13

On 12 April, a German officer rode up to the group on a motorcycle and informed the POWs, in perfect English, that President Roosevelt had died. William Shapiro recalled, “He said, ‘It is a sad day for Germany.’ I did not understand nor appreciate what he had meant by Roosevelt’s death being a sad day for Germany. Many years later, I presumed that he was frightened of the Russian advance and political takeover. . . . I remember that we all began to cry and this, superimposed upon our existing anguish, brought us to hopeless despair. After all this suffering, I thought there was no hope, no chance for liberation. I was lost—did not know where I was, what was going to happen to me. I remember some sort of makeshift memorial service that we had for President Roosevelt.”14

The village of Thierstein. (Author photo 2004)

A week after the American POWs left Berga to wander the roads of Bavaria, the political prisoners who had remained behind finally were marched out of their compound. Ernest Michel recalled, “The camp was evacuated on April 11. The reason I remember it so well is because the following day President Roosevelt died. The camp commander announced that ‘the war-monger Roosevelt is dead and now Germany is going to turn it around and win the war.’ The only American names I knew at that time were Franklin Roosevelt and Eisenhower. Don’t forget—we had no access to news. We just heard it through the grapevine. Those were the only two names I knew.”

To “celebrate” Roosevelt’s death, the SS shot ten prisoners. “We were walking at that time,” Michel said, “marching through a small woods, and they shot them in the woods. The shooting of prisoners went on about every other day. My friends—Schwartz and Munk—and I knew what was happening and we decided that the only way to avoid getting shot was to escape; we didn’t want to be shot and killed. So, on April 18, we escaped. Even the SS has to sit down and relieve themselves. During one of these periods, while walking through some woods, we decided to slowly move to the back and into the woods, into lots of small trees. That’s how we escaped.”

The trio spent the first three days and nights moving through the dense forests, hoping not to be seen, sleeping in the daytime, and walking at night. “We were going in a westerly direction, because this is where we knew the Americans and the Allies were coming in to Germany. But we were starving; the only thing we had to eat was grass and the bark of trees and maybe a rotten potato. We were literally starving.”15

The POW group rested until 13 April. Peter Iosso called the five days of rest “the only bright or redeeming event of my whole POW experience.”16

One of the German soldiers later reported that an order reached the group, an order “to set the POWs free in the various villages and to bring the troops across the Danube. It [Battalion 621] was ordered to reach the city of Wörth.” Then, on 13 April, a Major Otto of battalion headquarters ordered Merz and Metz to disregard the order to set the prisoners free.17 The parade of death staggered through Rehau, Schönwald, then onto the high tableland near Thierstein. But the POWs began to drop at an alarming rate—some from exhaustion, some from disease, some from the savage beatings they received at the hands of their guards. Eight men died and were buried at Rehau. At Thierstein, a week later, four Americans were buried in a common grave in the town cemetery beneath a cross inscribed in German, “Here Lay 4 American Prisoners of War 15 April 1945.”18

Thierstein town cemetery. (Author photo 2004)

Marienkirche (St. Mary’s Church) in Fuchsmühl, near the hospital to which some of the sick POWs were taken. (Author photo 2004)

When the group reached Fuchsmühl, Kommandoführer Metz allowed a group of the most seriously ill prisoners to be taken to the town’s hospital. They received no medical care and slept on straw.19

Close on the heels of the POWs was the 357th Regiment of the 90th Infantry Division. The regimental historian wrote,

At Fuchsmühl, 33 Americans were found lying in straw bunks. To describe their condition would be to play upon the imagination of the reader. They had been forced to work long hours in salt mines [sic] on a ration that was a disgrace to humanity. At the time of rescue, most of these men had declined to the point where they were unable to move from their bunks. . . .20

Day after day, mile after mile, the pitiful column plodded southward, uphill and downhill, struggling to put one foot in front of the other, with the stronger GIs helping support the weaker ones, continually spurred on by their captors with the promise that they were just going as far as “the next town.”

At some point during the march, Captain Merz was replaced by a Captain Hahn, but the lives of the POWs did not change appreciably.21

According to Peter Iosso, the group “dragged ourselves over the roads of eastern Germany, covering fifteen to thirty kilometers per day and spending the nights sleeping in barns or open fields. One whole day we slogged through freezing rain. Food was an uncertain commodity. Some days we got none. Others, the group got random numbers of loaves of bread at hastily set up points of distribution.”22

On 22 April, their courage bolstered by their desperate hunger and because they spoke fluent German, the political prisoner trio of Michel, Munk, and Schwartz dared to approach an isolated farmhouse near Lindenau and knocked on the door. “This was the one area in all of Germany that was never occupied,” Michel noted. “Not by the Allies, not by the Russians—nobody. A woman came to the door. I covered my arm with the tattooed Auschwitz number, and the others did, too. We told her we were on a work detail and were bombed out by the Allies, and could we get something to eat? She closed the door and we thought that was the end of it. Then she came back with some milk and bread and sausage. That was the first food we had. As a result, the three of us stayed in that area; each one of us worked on a different farm. It was April and the German farmers obviously needed hands to help work the farms, so each one of us stayed at a separate farm in the same neighborhood, and they left us alone. They gave us something to eat and let us sleep in barns, but at least we got food. That was a lifesaver.”23

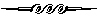

Tony Acevedo’s 1950 sketch of the “death march.” POWs are pushing and pulling the “sick wagon,” while being followed by small, remote-controlled “Goliath” tanks. The bodies of dead political prisoners, murdered by their Nazi guards, line the roads. (Courtesy Tony Acevedo)

As the endless kilometers passed step by agonizingly slow step, the ordeal of the American POWs began to take on the character of the fruitless labors of the mythical Sisyphus. The elderly Volksturm guards that accompanied the column were suffering almost as much as the POWs. But the guards had rations and water to sustain them; the prisoners were fed only when they stopped for the night.24 During the march, Kommandoführer Metz, ever eager to prolong the suffering of the prisoners, forbade compassionate German civilians from giving food to them.25

The POWs began to make out a large body of political prisoners moving along the highway a few miles ahead of them. Soon, the lovely spring landscape began to reveal its incongruous horrors. The road climbed a rise and, as the Americans struggled uphill, they noticed up ahead what looked like odd bundles littering the ground. As they got closer, the bundles became clumps of gaunt corpses carpeting the road, sprawled in ditches, and hanging limply from barbed-wire fences. Each one had a bullet hole in its head. They were the political prisoners the POWs had been following.

Gerald Daub remembered, “As we approached this hill, we saw a few prisoners lying by the side of the road in these atrocious pleading and praying and frightened positions—all shot. I didn’t hear any shooting or see the incidents. We just saw them lying there dead and it was very grotesque, I mean, just the way they were lying there in these grotesque positions. Somebody asked the guards what had happened and they said American planes had strafed them, but we knew that was not true because all of them were shot in the head. It seemed as though we marched all that day, and practically all we saw were these bodies along the side of the road.”26

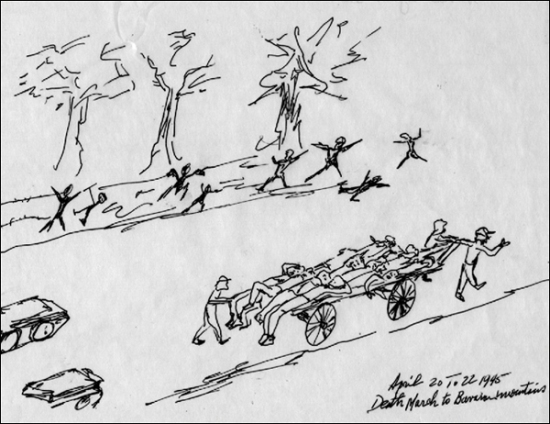

Today, the route of the Totenmarsch (death march) is pastoral and bucolic, offering no hint of its previous horrors. (Author photo 2004)

Medic William Shapiro was aghast at the sight. “During my five months of front-line combat, I had witnessed many instances of gore—dismembered and blown-apart bodies. Dead soldiers were a common sight. But this scene on the ‘Death-March Road’ was significantly different. . . . As we approached a steep hill, I saw the most gruesome, cruel, barbarous, inhumane acts that I have ever seen in my entire life. As we climbed the hill and caught up to where we had seen the political prisoners in the distance, we saw on each side of the road hundreds of dead Jews. Most of them were in the kneeling position, many on their side in a fetal position and all were dead by obvious gunshots behind the head. Many heads were blown open by the force of the shot, and the brains were splattered about. It was ghastly. It was indescribably frightening. It was unspeakable. It was so shocking to look at the very recent, awesome destruction of human beings. The murder was, presumably, because they could not continue the march up the inclined road. . . . What was in store for us? Is this the manner in which it will all end? The horror of it reflected onto me and my overwhelming despair. After all the suffering that these Jews had encountered, so close to freedom, their inability to climb the hill resulted in instant death.

“I was exhausted and just dragged along, fearful of stopping until we were told that it was time for a break. I became an automaton. As we continued to walk through them and past them, we came to another group of political prisoners in similar positions. As we ascended the steeper part of the hill, there were more and more victims. You became immune to the sight. You expected it. It was walking into a hell. The ‘trees’ lining the sides of the road to hell were dead Jews. I could never imagine anything as macabre as this massacre. As we were catching up to the civilian prisoner march, we began to hear the firing of machine-guns and burp guns in the woods a short distance from the road. We could not see the Jews, but we knew what was happening in those killing woods among the pine trees which blocked our view.”27

Joseph Mark was stupefied at the scale of the crime: “We passed a section where I saw dead Jewish concentration camp victims lying in the road every few feet, for over a mile. I thought maybe they were Hungarians, but I’m not sure. The Germans were marching them somewhere. They were just concentration camp victims in striped suits from other camps, and the SS just shot them in the head. Our guards gave us a little special treatment as soldiers, because they knew there were German soldiers that were POWs in the U.S., and they marched us as soldiers.”28

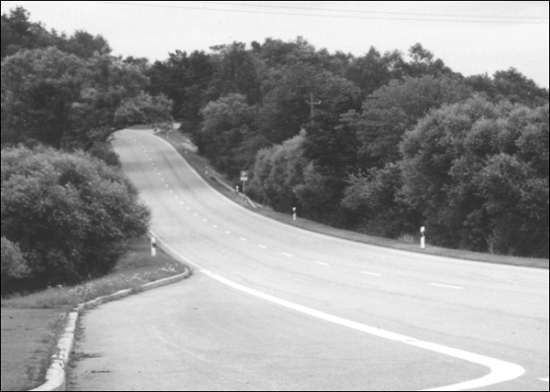

Steep road near Oberviechtach, climbed by the POWs. (Author photo 2004)

Tony Acevedo was equally appalled. “Up ahead, the Germans were slaughtering the Jews from another camp. They were slaughtering old people, young people, women, children, everyone. We saw people hanging from the barbed wire fences on both sides of the highway, hanging down, slaughtered by the machine-guns of the Germans.”29

To Peter Iosso, the march “was like a descent into hell, spiritually and physically. Death and thoughts of death were ever present. We saw huge masses of political prisoners in open fields, some being shot for breaking ranks, the others with little hope for a better fate. As a matter of fact, for two whole days we walked on a road lined on both sides, at about three-foot intervals, with dead political prisoners who had neat bullet holes in their heads. We wondered where we were headed and whether we’d ever get there and, if we did, what good it would do. There were rumors of ovens.” On 19 April, Iosso managed to drop out of the column but was captured and spent a night in a local town jail; he was returned to the group by wagon the next day.30

The 357th Regiment of the 90th Division, still trying to catch up with the American POWs, also found the evidence of German atrocities. The regiment’s historian noted,

The unburied bodies of the ones who were unfortunate not to be able to walk any farther were seen all along the roads. Many had been shot in a group and shared a single uncovered grave. Many thousands of British prisoners of war were also liberated. Some of the chaps had been taken at Dunkirk and had been with the Germans for five years.

The sight of these liberated prisoners of war and slave laborers from other nations wrung pity and pride from the hearts of all, and brought to everyone’s mind the real reason why America was fighting this war. The deplorable condition of these unfortunate people brought stark realization of the true value of democracy and its worth to freedom-loving people.31

The scene of wholesale death was the last straw for Morton Brooks; he had had enough, and decided he would rather perish while escaping than be shot like a helpless animal. “This friend of mine, Sam Fahrer, and I attempted an escape; we just dropped back until we were trailing and it was getting dark and the guard in the back didn’t seem to be that concerned about us. We eventually took off into the woods, but we didn’t get away for long. Fahrer tried to go up and get some food from a farmhouse but the farmer came out with a gun and we were taken into a town and put into a kind of dungeon. I guess they found out where we came from and we were returned to the group.”32

The death march continued to take its toll on bodies that were seriously weakened by disease and malnutrition. Men continued to die on the route to nowhere. “I didn’t think I could live much longer,” Joseph Mark admitted. “Like a few more days, at most. I weighed about eighty-five pounds and I could feel the ligaments I was walking on.”

A roadside crucifix along the “highway of death.” A grotto like this one gave Joseph Mark hope for liberation. (Author photo 2004)

An unexpected scene then caught Mark’s eye. The state of Bavaria is predominately Catholic, and most of the villages have roadside grottoes—graphic depictions of a suffering Christ on the cross. Mark said, “I was so moved by the sight that it brought tears to my eyes—and I’m a Jew! I have nothing to do with Jesus! In a land of Nazis and Hitler, the sheer humanity of Jesus got across to me—it was the only humanity that I saw in all the time that I was a prisoner. Then, as we rounded the turn after seeing this statue, there were two buxom, Bavarian women cutting large slices of black bread and handing them to us.” The act of kindness enabled him to carry on with renewed hope that the group would soon be liberated.33

Approaching Rötz from the direction of Neunburg. (Author photo 2004)

On April 20—Hitler’s birthday—the guards from Berga were relieved by a new set of guards. Kommandoführer Metz was also relieved, but the march and its attendant agonies continued. Joseph Mark said, “They changed the guards because some of our guys had it in for the guards. These were new guards and they made us a thick soup, which the Germans call dicke zuppe. At Berga, the soup was so thin, I used to wash my socks in it.”

In spite of the hearty soup and kinder treatment, Mark felt that everyone had reached the limits of his endurance. Somehow, in one of the most amazing feats of human resilience, the group of survivors had managed to walk 300 kilometers in three weeks. “About the twenty-second of April, we wound up off the road at a barn that was up in the hills near Cham.* There we just fell into a slush of cow urine. At that point, you just didn’t care. You just wanted to die.”34

The liberators close in on the POWs at Rötz, April 1945.

On the night of 22 April, the POWs were resting in the barn, their sore and blistered feet bleeding, their spirits at their lowest ebb. All seemed hopeless; death seemed near. Morton Brooks recalled, “We had been bedded down in a barn for the night along the road; we were exhausted. We had been marching for three weeks. We decided that, when the Germans tried to get us up in the morning, we would not move.

Some of the surviving POWs identified this barn, located on the northern edge of Rötz, as the one in which they were held the night before their liberation. (Author photo 2004)

“The next day, we heard the guards say, ‘Raus! Raus!’ The word went through the barn: ‘Don’t move,’ and we just laid there. A couple of minutes later, we heard some shots and the guards took off. After about ten or fifteen minutes of quiet, one of the fellows looked out the back end of the barn. We were on a hill and it sloped down from the back and he saw American tanks coming up the road, and some of our fellows shouted, ‘Americans!’”35

*The group had reached the town of Rötz, a few miles north of Cham.