Who Are the Superrich?

A World Economic Forum panel in January 2015 discussed the rise of the superrich. Winnie Byanyima, the executive director of Oxfam, began the conversation with the observation that in 2014, 85 people had as much wealth as the bottom 50 percent of the world’s population and that in 2015, 80 would have as much. She expressed concern about such extreme inequality as a worrisome trend, irrespective of how worthy were the means by which the wealthy achieved their success.1 Sir Martin Sorrell, CEO of WPP, a large marketing firm, retorted, “I make no apology for having started a company 30 years ago with 2 people and having 179,000 people in 111 countries and investing in human capital each year to the tune of at least $12 billion a year.”2 His comment showed that it was wrong to label all wealth as inherently worrisome because in his case it resulted from an enterprising initiative that benefited many others.

Is the increase in extreme wealth around the world a worrisome trend, regardless of how it was gained or invested, as Byanyima fears, or a source of economic growth, as Sorrell proposes? Is it indicative of less legitimate methods, such as state capture, favoritism, unfair advantage (inheritance or access to resources or monopolies)? Or is it a reflection of the value of prosperity, as new businesses flourish and create jobs? This chapter identifies different types of wealth by presenting a taxonomy that attempts to separate “company creators” from other members of the superrich class and understand how this group has changed over time. Its argument is that the growing importance of independent company creation has brought wide benefits in poor and emerging economies and that these gains must be evaluated in a broader context than simply a judgment of whether inequality itself is bad for a country.

Self-made billionaires represent a growing share of the world’s billionaire population. But much of their wealth comes from finance and politically connected/rent-related activities. For the world as a whole, the share of billionaires who founded companies has been roughly flat at nearly 30 percent.

These global trends, however, obscure significant variation between advanced countries and emerging markets. Emerging-market billionaires are more likely to be self-made and their wealth tied to government-related activities. The share of billionaires who are company founders in emerging markets is on the rise, while inheritors are in decline. In contrast, in advanced countries, wealth shares are relatively stagnant, with a modest decline in inherited wealth and company founders and an increase in finance-, rent-, and government-related wealth.

This chapter presents theories about why extreme wealth has grown. It identifies five types of billionaires: people who inherit wealth, company founders, executives, government-connected or rent-related billionaires, and finance and real estate billionaires.

How and Why Do People Become Very Rich?

Economic thinking offers three broad explanations for the extraordinary rise of top incomes and wealth in recent decades.

Superstardom

The first theory, associated with Alfred Marshall (1890) and more recently Sherwin Rosen (1981), puts exceptional ability, technological change, and globalization at the heart of extreme incomes and hence wealth. According to this view, growth in extreme wealth stems from changes in the environment that have made today the right time and place for superstars to create and grow truly innovative enterprises. The “superstar” theory argues that new technologies allow people to communicate more easily, enhancing returns to scale, while globalization provides a nearly unlimited audience. With new communications technology, a superstar manager can now manage people around the world, just as a superstar singer could be heard globally following the advent of recording devices. Lower barriers to trade and investment and cross-continental travel yield access to a wider customer base and allow for more efficient production techniques. Just as Hollywood stars attract wide audiences and large salaries, while starving actors abound, company leaders now reap enormous rewards while middle management stagnates. As a result, superstars in many fields, especially new technologies, are in high demand and earn extraordinary wages while demand for the skills of most people remains stagnant or worse.

Technology has rewarded many superstars, such as Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook (number 21 on the 2014 Forbes World’s Billionaires List), and Azim Premji (number 61), the founder of India’s third-largest software outsourcing firm, Wipro. But techies are not the only billionaire entrepreneurs: Trade and technology have also rewarded goods producers. Amancio Ortega, the founder of the international clothing retailer Zara, is the world’s third-richest person. More than 70 percent of his stores are outside his home country of Spain. Trade is also important for He Xiangjian of China (190th on the Forbes list), whose fortunes stem from the appliance producer Midea, which earns about half of its revenues from exports.

Extraction of Rent

The superstar theory presumes entrepreneurship on the part of the rich. But not all wealth is acquired in virtuous ways. Extraction of rent is the second broad explanation proposed for the rise in extreme wealth. It is potentially more important in emerging markets, where institutions are less developed. This argument emphasizes government interventions, such as privatization and regulation, soaring asset prices, and changes in corporate culture and social norms, all of which allow a larger share of rents to accrue to a small group of capital owners without a corresponding rise in the real productivity of capital or its owners. Unlike the wealth created by superstars, this type of extreme wealth does not improve allocative efficiency.

Examples of rent extraction include much of the oil wealth in emerging markets as well as a number of underpriced privatizations. Nigeria’s Foloronsho Alakija (number 687 on the Forbes list) benefited from a cheap oil license granted by the government. Her wealth expanded dramatically as oil prices surged in recent years, bringing her to the Forbes list for the first time in 2014. Russia’s Igor Makarov (number 828), who first appeared on the list in 2012, became a billionaire following a joint venture with Rostneft, the Russian state oil company.

Not all rent-related wealth comes from natural resources. Brazil’s Cesar Mata Pires (number 1,143), founder of construction company OAS, appeared on the list for the first time after winning the government contract (and subsidized government loans) to build Brazil’s 2014 World Cup stadiums.

The third source of expanding wealth is inheritance, which leads to a consolidation of wealth if returns to wealth exceed growth and capital grows rapidly. Thomas Piketty argues that because historically capital earns higher returns than labor, the rich will continue to get richer unless global tax policies change. Inheritance plays an important role in this theory, because capital’s share of income grows faster than labor’s share. For this phenomenon to increase inequality over the long run, it must be the case that capital is not easily created or destroyed. France’s Liliane Bettencourt, one of the richest women in the world, is a prime example of the growth of inherited wealth. In 2000 her estimated net worth was $15 billion; by 2014 it had more than doubled to $38 billion. This fortune accumulated as a result of her large stakes in L’Oréal and Nestlé.

However, large inheritances do not always grow, as the relatively high return on capital that Piketty worries about is an aggregate measure and reflects returns to many different investments both old and new. Carlos Peralta, for example, inherited a manufacturing and construction conglomerate from his father. He expanded into telecoms with the help of a cell phone license awarded by the government, putting him on the Forbes list from 1999 to 2004. His fortune reversed in 2005 as the Mexican economy became more competitive, taking him off the list. In 2009 the global recession hit his businesses hard, forcing him to put his 257-foot yacht and Trump Tower apartment on the market.

Because of new wealth creation and the fact that a good deal of old wealth is destroyed, inherited wealth has not been growing as a share of total wealth in either the North or the South.

Determinants of Extreme Wealth

Empirical research on the rise of the superrich—most of which focuses on the developed world—is inconclusive. Some evidence suggests that technology and globalization are the sources of extreme wealth. Other research finds that the rise in asset prices and changes in corporate governance are key.3

Little academic research has explored the phenomenal rise in extreme wealth in emerging markets. But private banks and consulting firms have jumped in to tap this growing market. The Boston Consulting Company has written extensively about the superrich in Asia, as both a byproduct of and a foundation for growth. Banks in Europe struggling with new regulations are “fighting over rich emerging-market clients to boost revenue.”4 Ruchir Sharma, of Morgan Stanley, has been tracking how billionaires in emerging markets made their fortunes to glean “a quick indicator of how well positioned emerging nations are to compete in the global economy.”5 With a similar goal in mind, the taxonomy presented in this chapter expands on the Forbes data to develop a methodology for comparing the sources of wealth across countries.

The 2014 Forbes World’s Billionaires List includes 1,645 individuals from 69 countries, 959 of them from advanced countries and 686 from emerging markets. The rise in extreme wealth in emerging markets over the past 10 to 15 years has been dramatic, with 42 percent of billionaires coming from emerging markets in 2014. The Forbes list is the longest series of data and includes the names of individual billionaires, facilitating research into the origins of wealth. Other data sources show similar patterns for the years for which they have data. Knight Frank and Wealth-X both put the emerging-market share at 43 percent. They also provide information on individuals worth tens or hundreds of millions of dollars. These data are useful to expand country coverage, as smaller countries often have no billionaires. Knight Frank (2014) finds that 25 percent of people worth $100 million and 22 percent of people worth $10 million or more are from emerging markets. These shares are about twice what they were a decade ago. Wealth-X and UBS (2014) estimate that 28 percent of the ultra-high-net-worth population (people worth $30 million or more) live in emerging markets.

This section compares the 2001 Forbes list to the 2014 list in order to better understand the composition of today’s billionaires. The 2001 Forbes list provided no information about the source of billionaire wealth. More recent lists include the company or industry associated with each billionaire’s wealth. The 2001 list is used as the first period because data from 1997 to 2000 use a different methodology to assign wealth to family members, making it incomparable at the individual level to other years.6

Distinguishing Self-Made from Inherited Wealth

Each individual on the list was investigated to determine whether his or her wealth was self-made or inherited and to identify the industry and company primarily associated with the wealth and the gender of the individual. Wealth was considered self-made if the individual listed was the founder of the company or the source of wealth resulted from the person’s position at a company. Billionaires who may have benefited from political connections or resource rents but did not inherit their wealth are also considered self-made.

Determining the extent to which wealth is inherited is more challenging than determining self-made wealth, because some billionaires inherited a fortune already in the billions when they entered the list while others built a smaller company into a billion-dollar one. In their analysis of the Forbes lists of the world’s billionaires for 1987, 1992, 2001, and 2012, Kaplan and Rauh (2013) distinguish between billionaires whose wealth is self-made, inherited, and built from a “modest business.” They find that inheritors of modest businesses make up less than 10 percent of total observations in both the United States and the world in 2012. They do not identify the cutoff for what constitutes a modest business.

In order to establish a clear cutoff, wealth is defined here as inherited if the 2014 billionaire is a relative of the founder of the company from which his or her primary source of wealth is derived. Using this definition provides a conservative estimate of self-made wealth and classifies billionaires who built smaller companies into billion-dollar ones in the inherited category. The most extreme example is Gina Rinehart, who built her $17.7 billion fortune from her father’s $125 million mining business. In the methodology used, her wealth is considered inherited because she did not found the (still relatively large) company associated with her wealth.

The one exception is billionaires who inherited a single store or small factory from their family. These billionaires, who constitute about 2 percent of the sample, are considered self-made. They include GEMS Education chair Sunny Varkey, who took over a single school with fewer than 400 students from his parents and turned it into the largest operator of private K–12 schools in the world.7

The Forbes data report a billionaire’s country by citizenship, as opposed to country of residence or birth. Using this citizenship variable, billionaires were divided into advanced countries and emerging markets. Countries in the first category include the high-income members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) at the beginning of the period (the United States and Canada, the countries of Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and Korea).8 All other countries are grouped into the second category.

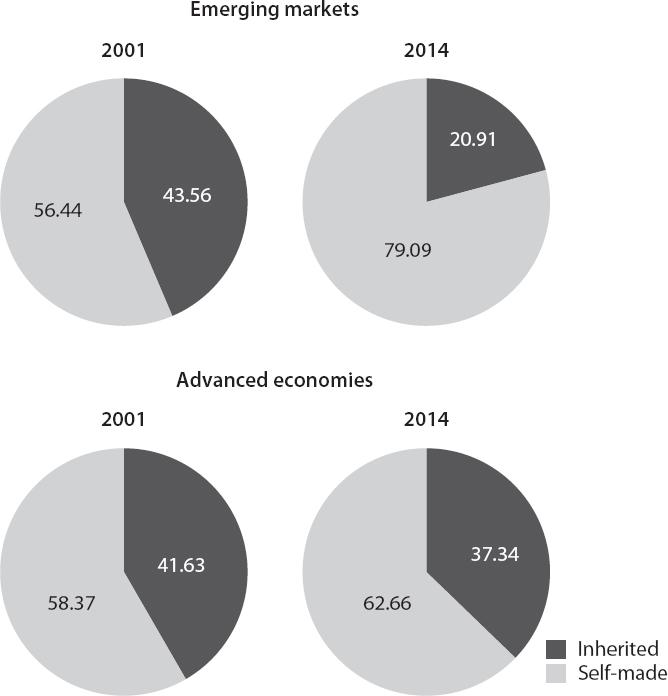

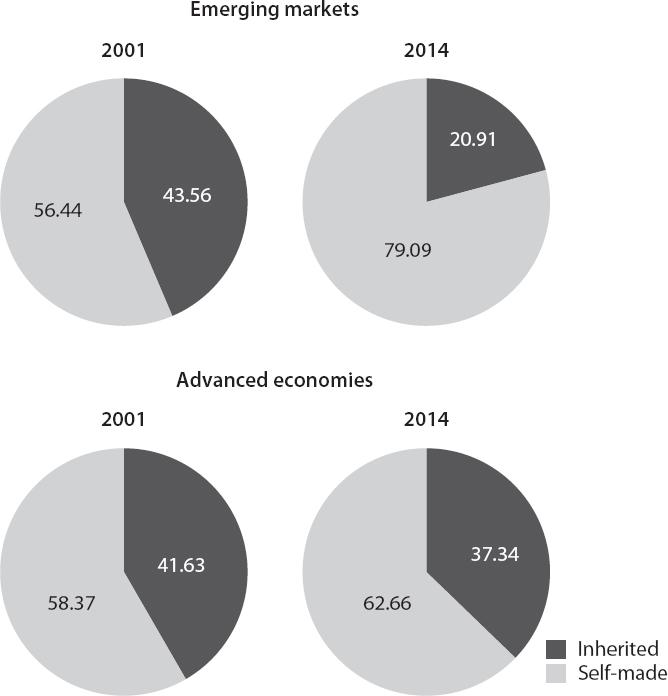

Figure 1.1 shows the share of billionaires by source of wealth in advanced countries and emerging markets in 2001 and 2014. Figure 1.2 shows the distribution of billionaire wealth. The number of billionaires and their wealth could be distributed differently if self-made billionaires are on average much wealthier than people who inherit their billions, who may split their fortunes with siblings.

Three facts emerge from these figures. First, even with this stringent view of inherited wealth, the majority of billionaires in both the advanced world and emerging markets are self-made. Second, the share of self-made billionaires remained broadly constant in the advanced world, at about 60 percent, but rose significantly in the developing world, reaching nearly 80 percent in 2014. Third, in each year and in each grouping, the percentage shares of the number of self-made billionaires and the aggregate value of their wealth are similar.

The share of billionaires that are self-made in 2014 is broadly consistent with research by Wealth-X, which estimates that 55 percent are self-made, 20 percent inherited their wealth, and 25 percent inherited some wealth and made the rest (Wealth-X and UBS 2014). The last category is defined as reaching “billionaire status through a combination of inheritance and hard work, either by starting their own business or taking an active role in their family businesses” (p. 25). The shares are roughly similar when the top of the distribution—where potential underreporting of inherited wealth, which tends to be more diversified and hence harder to track, is likely to be less of an issue—is examined (Freund and Oliver 2016).

Figure 1.1 Share of self-made billionaires in advanced economies and emerging markets, 2001 and 2014 (percent)

Source: Author’s calculations using data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires, 2001, 2014.

Classifying Billionaires Who Did Not Inherit Their Wealth

The superrich who did not inherit their wealth are classified into four broad categories: company founders, executives, government-connected or rent-related billionaires, and financial and real estate sector billionaires. This classification is likely to understate the size of the entrepreneurial class, because some of the winners of privatizations are highly skilled entrepreneurs who turned around weak state enterprises and many financial sector billionaires facilitated the development of new companies or helped create infrastructure for development. In addition, some billionaires who inherited wealth, such as Ratan Tata or Lee Kun-hee, presided over phenomenal company growth. Resource wealth may also benefit from leaders who make smart investment decisions, expanding scale, improving technology, and tightening the logistics of their companies.

Figure 1.2 Share of self-made wealth among billionaires in advanced economies and emerging markets, 2001 and 2014 (percent)

Source: Author’s calculations using data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires, 2001, 2014.

Company Founders

Many billionaires become extraordinarily rich because of innovation, especially in fast-growing markets. Jan Koum and Brian Acton (combined net worth of $10 billion) of WhatsApp, a phone-based instant messaging service, first appeared on the list in 2014, after Facebook bought their app. Zhou Hongyi and Qi Xiangdong, of Qihoo 360, are together worth more than $3 billion. They captured the Chinese internet security market by offering their basic product free of charge and generating revenue through premium services. Both men appeared on the list for the first time in 2014.

Other billionaires got rich quickly with the help of political connections. Vagit Alekporov of Russia (worth $14 billion) was appointed deputy minister of oil and gas in 1990 and then catapulted into the lead position of Russia’s largest private oil company, Lukoil, in 1991. Denis O’Brien of Ireland (worth $5.3 billion) won a valuable mobile phone license in 1995 with the aid of a politician.9

In order to conservatively estimate the number of company founders on the Forbes list who created innovative products, we exclude fortunes made in finance and real estate, natural resources, and political connections in the company founder category. Company founders thus most closely resemble the billionaires one thinks of as superstars: the people who invent new products that millions of people know and use or develop new production processes that expand varieties and reduce consumer prices.

Executives

A second category of self-made wealth includes people whose fortunes come from their position as an executive at a particular company (such as Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg) that is not related to political connections, finance, or natural resources. Billionaires described as the chair, CEO, or other leader without also being listed as the founder are coded as executives in the dataset. This group also includes individuals who own a company but are not explicitly listed as a founder or given an executive title, such as billionaires who inherited a single store or factory.

Government-Connected or Rent-Related Billionaires

Fortunes stemming from political connections or natural resources are characterized as government connected or rent related.10 A billionaire is identified as politically connected if there are news stories connecting his or her wealth to past positions in government, close relatives in government, or questionable licenses.

Also included in this category are self-made billionaires whose companies are privatized state-owned enterprises. By definition the acquisition of a state-owned company is connected to the government, as the transaction requires agreement from the government. Although privatization often results in better-managed firms, so some wealth accumulation is to be expected, this classification is made because the accumulation of $1 billion or more in wealth via privatization is suggestive of an underpriced deal. Rents accrued to the purchaser were likely more dependent on the company’s business than the talent of the buyer.

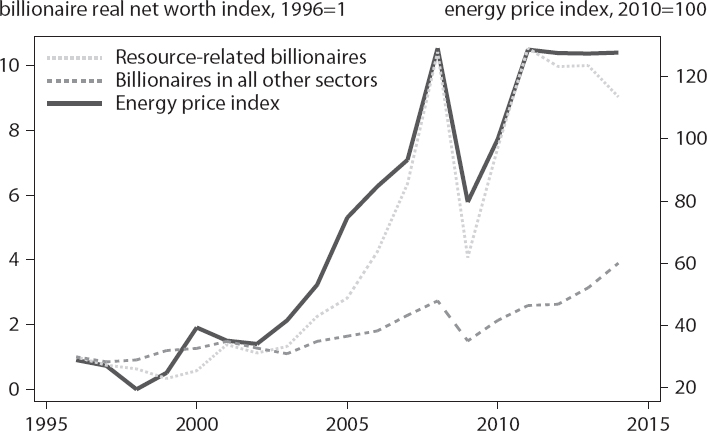

Figure 1.3 Indices of real net worth of billionaires and energy price, 1996–2014

Sources: Data from World Bank, Global Economic Monitor (GEM) commodities database; and Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Self-made billionaires whose wealth originates in resource-related industries, including oil, natural gas, minerals, and coal, also fall into this category, because control over the area in which the resource is found is frequently determined through government contracts. Although some resource companies benefit from strong management, much of their return is outside their control, a function of prices. The windfall of resource wealth is so well accepted that providence as opposed to skill was the argument given in the recent divorce settlement of oil magnate Harold G. Hamm from Sue Ann Arnall. Hamm was not required to share half the wealth from his company, after more than 25 years of marriage, because his lawyers argued that the value of the company was a result of “passive” appreciation and not his ability as a CEO.11

The importance of external factors, as opposed to talent, in determining resource wealth, is demonstrated in figure 1.3, which shows the growth in total real net worth of resource-related billionaires compared with all other billionaires between 1996 and 2014.12 The growth is nearly perfectly correlated with energy price movements.

Financial and Real Estate Sector Billionaires

Financial sector billionaires are also treated separately. Some of them, including investors who backed new and innovative companies early on, are superstars. Others benefited from political connections, weak regulatory oversight, and insider trading. The global financial crisis makes it especially hard to declare this group as genuine innovators, although some are. Many used brilliant strategies to channel much needed capital into high-growth firms, making big profits and promoting growth and jobs. Others found new ways of ensuring that markets are properly priced. The group of financial innovators includes Peter Thiel, a hedge fund manager who cofounded PayPal and was the first outside investor in Facebook; Bruce Kovner, the “inventor” of carry trade (the selling of currencies with low interest rates to buy currencies with high rates); and Petr Kellner of the Czech Republic, who developed Home Credit, a product that allows lower-middle-income individuals to access credit in 10 emerging markets, including Russia, India, Indonesia, China, Vietnam, and the Czech Republic.

Other financial-sector billionaires benefited from weak government oversight, sweetheart deals, and in some cases outright corruption. Michael Milken spent 22 months in prison for securities fraud but remains on the Forbes list, with assets of more than $2 billion.13 Less well known but richer, with an estimated net wealth of nearly $10 billion, is Steven Cohen, the head of SAC Capital Advisors, a firm caught in a web of insider trading in 2013.14 Indonesian investor Murdaya Poo managed to keep his fortune despite his wife’s 2013 conviction of bribery to gain land concessions.15 Wong Kwong Yu of China is serving 14 years in jail for insider trading and bribery.16

Also included in this category are real estate billionaires. Some benefited from government land concessions, others helped develop urban areas; many did both. China has the largest number of real estate tycoons in the South. They have promoted development by building the infrastructure that is supporting China’s growth, but in a country where land is owned by the government and leased to the private sector, many are closely tied to politicians. The New York Times recently profiled the richest of the Chinese real estate moguls, Wang Jianlin, whose company, Wanda, is building skyscrapers, shopping malls, and theater complexes throughout China.17 According to the Times, the elder sister of China’s President Xi Jinping, the daughter of former prime minister Wen Jiabao, and relatives of former Politburo members all have large stakes in his multibillion-dollar company, though there is no evidence that they intervened on the company’s behalf with the government.

Analysis

Table 1.1 shows the distribution of billionaires and their wealth across the five categories of billionaires in 2001 and 2014. The largest group within the self-made category in both years is company founders. The striking difference between 2001 and 2014 is the expansion in resource-related, privatization-related, and politically connected billionaires, whose share more than doubled in terms of both number and total wealth, at the expense of inherited wealth. There are notable differences between billionaires in the North and the South. Self-made billionaires in all categories except finance expanded their shares in emerging markets. In 2001, for example, just 12 percent of billionaires in emerging markets were company founders; by 2014 that figure had risen to 24 percent. The share of executives also jumped, from 5 to 11 percent. The shares of billionaires who owed their fortunes to government connections/rents or finance were flat. Shares changed less in advanced countries, where the greatest change was the small decline in inherited wealth and the concomitant increase in the shares of billionaires who got rich through finance or through government connections.

Table 1.1 Distribution of number and wealth of billionaires, by source of wealth, 2001 and 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Author’s calculations using data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Extreme wealth today is largely self-made, and the self-made share is growing, driven by emerging markets. Among self-made billionaires in emerging markets, the share of company founders and executives (excluding resource-based companies and privatized state enterprises) is growing exceptionally quickly, as the share of inherited money declines. The new emerging-market entrepreneur is one who builds a globally competitive mega firm, changing the economic landscape in his or her home country.

The picture is less dynamic in the North, although the share of inherited wealth is declining there, too. A worrisome trend is that it is being replaced by politically connected wealth and wealth from finance rather than wealth created by founders of firms.

1. “Davos: A Richer World—But for Whom?” BBC, January 23, 2015.

2. Ibid.

3. Facundo Alvaredo et al. (2013a) argue that there is a wide variety of outcomes in advanced countries—with some countries but not others showing a sharp increase in income at the top—indicating that forces common to all industrial countries, such as new technology and globalization, cannot be responsible for the rising share of the top 1 percent. Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez (2013) echo this view, noting the strong correlation between the income of the top percentile and reductions in top tax rates. Using detailed US income tax data for 1979–2005, Jon Bakija, Adam Cole, and Bradly Heim (2012) find stark differences in pay differentials across occupations. They show that executives, managers, supervisors, and financial professionals account for about 60 percent of the top 0.1 percent in recent years and argue that asset prices and possibly corporate governance are the primary sources of the increase in extreme wealth. Steven Kaplan and Joshua Rauh (2013) examine both income and wealth in the United States and find in favor of technology, largely because change is spread broadly across occupations.

4. “BNP Paribas Targets Asian Super-Rich to Boost Wealth Business,” Bloomberg, March 7, 2013.

5. “The Billionaires List,” Washington Post, June 24, 2012.

6. In 1996 and from 2001 to 2014, billionaires are reported as individuals. However, from 1997 to 2000, the list aggregates individual billionaires by family. As a result, the number of billionaires is systematically lower in these years and the average net worth of billionaires is systematically higher. These years can be used when considering aggregate net worth or examining wealth at the country or industry level; they cannot be used to analyze trends at the individual level, since this difference makes these years incomparable to later years.

7. For a detailed explanation of the methodology used to create these data, see Freund and Oliver (2016).

8. As a result of this decision, some high-income economies, including Taiwan and Singapore, are grouped in the South. Many of the billionaires and mega firms in these economies are from mainland China or produce in China or for the Chinese market. Wealthy Gulf nations are also classified as emerging markets. Although these countries are rich in oil, they have yet to experience the structural transformation that would qualify them as modern economies. Results remain qualitatively unchanged if these countries are not included in South.

9. Michael Moriarty, “Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry into Payments to Politicians and Related Matters, Part II,” March 2011, www.moriarty-tribunal.ie/asp/detail.asp?objectid=310&Mode=0&RecordID=545.

10. Suthirtha Bagchi and Jan Svejnar (2013) also characterize the Forbes data according to political connections. If they find evidence, using Lexis Nexis searches, that the individual would not have become a billionaire in the absence of political connections, they deem the person to be politically connected.

11. Robert Frank, “Are CEOs that Talented, or Just Lucky?” New York Times, February 8, 2015.

12. Real net worth is the net worth of billionaires in 1996 US dollar terms. For an explanation of the methodology, see Freund and Oliver (2016).

13. Scott Cendrowski and James Bandler, “The SEC Is Investigating Michael Milken,” Fortune, February 27, 2013, fortune.com/2013/02/27/the-sec-is-investigating-michael-milken.

14. Michael Rothfeld, “SAC Agrees to Plead Guilty in Insider-Trading Settlement,” Wall Street Journal, November 4, 2013.

15. Ben Otto and Joko Hariyanto, “Indonesia Businesswoman Convicted of Graft,” Wall Street Journal, February 4, 2013.

16. #149 Wong Kwong Yu and family, Forbes China Rich List, www.forbes.com/profile/wong-kwong-yu.

17. Michael Forsythe, “Billionaire at the Intersection of China’s Business and Power,” New York Times, April 29, 2015.