Billionaires, by Region and Sector

Billionaire wealth in emerging markets has been growing much faster than wealth in the advanced countries in recent years. A great deal of this wealth has accrued to founders of big global companies—people like Cyrus Poonawalla of India, whose Serum Institute makes more polio vaccine than any other company in the world, and Miguel Krigsner, who owns Grupo Boticario, Brazil’s second-largest cosmetics company. Most emerging markets have produced this new breed of highly productive businessmen, but some regions and countries have outperformed others.

East Asia is especially dynamic, with 115 company founders (excluding finance and real estate) in 2014. Many are well-known individuals, like Terry Gou, the founder of Foxconn, which makes iPads, and Jack Ma, the founder of Alibaba, the online marketplace. Many of the new companies are competing in the tradable sector and in new sectors (relatively contestable industries), not in resources and telecoms, as in the past. Political connections and resources are still mainstays of extraordinary wealth in Latin America and emerging Europe, but even there the number of company founders has grown. Even Africa, where a decade ago all wealth was inherited, has a growing share of company founders. Many, like Christoffel Wiese, the founder of Pepkor, a clothing retailer in Africa, are from South Africa.

Such self-made founders account for an increasing share of wealth in emerging-market regions, with the important exceptions of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and South Asia. In South Asia great fortunes associated with political connections and finance have been on the rise, and MENA is increasingly dominated by inheritance. These trends in regions known for their failure to integrate into the global economy are disturbing.

This chapter examines how billionaire wealth varies across sectors and regions. It also identifies the industries in which billionaires are concentrated.

Billionaire Data around the Globe

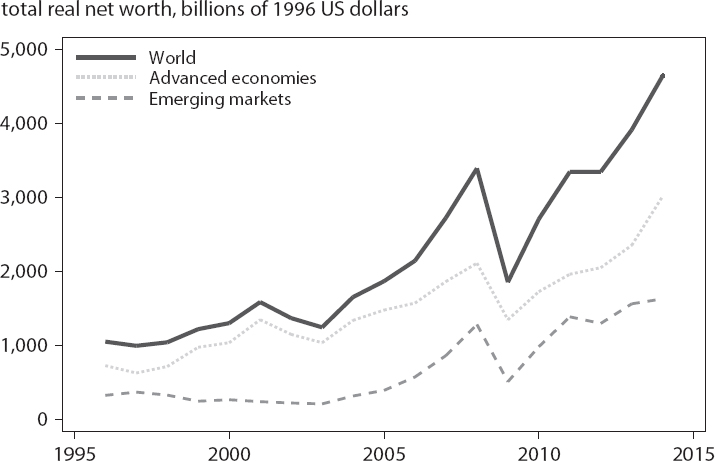

The real net worth of the world’s billionaires increased rapidly between 1996 and 2014 (figure 2.1). The rapid growth in real net worth in emerging markets began in the mid-2000s; earlier growth centered in the advanced countries. Both advanced countries and emerging markets experienced a sharp drop in total net worth in 2009, but by 2014 the total real net worth of billionaires exceeded 2008 levels for both groups.

Figure 2.1 Total real net worth of billionaires in advanced economies and emerging markets, 1996–2014

Sources: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires; and World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Which Sectors Account for This Growth?

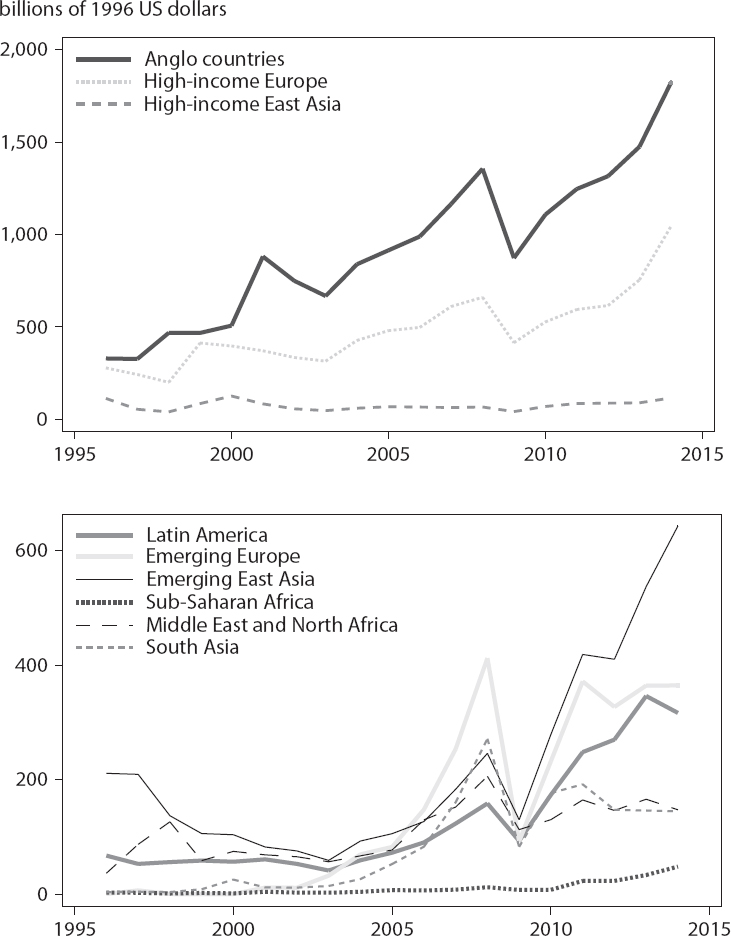

Wealth comes from five broad sectors: resource related, new, traded, nontraded, and financial. Table 2.1 identifies the major industry categories in each sector.

The resource-related sector includes all natural resources as well as steel. Steel is included in this category because the key inputs needed for its production (coal and iron ore) are major components of the resource sector. The “new” sector captures the effect of changing computer and medical technology on billionaire wealth. Traded sectors are separated from nontraded sectors in order to assess the impact of trade openness and globalization. Construction is considered a nontraded sector. Real estate is grouped in the financial sector, because real estate investment more closely resembles an asset than a good or service for consumption.

Table 2.1 Sector classification

a. Accounts for less than 5 percent of observations.

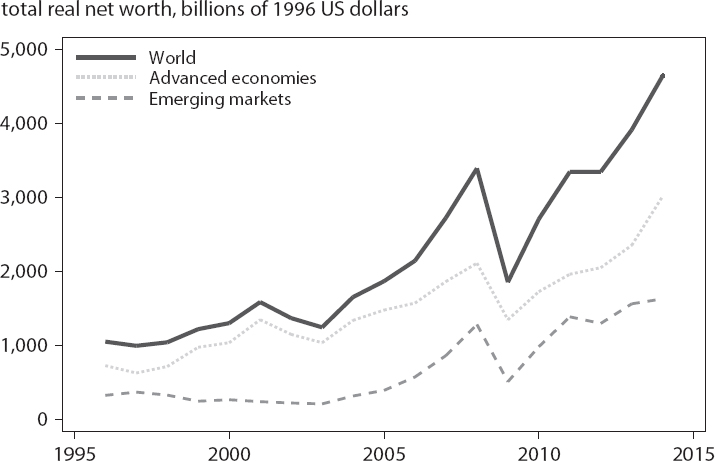

Table 2.2 Distribution of number and wealth of billionaires, by sector, 1996 and 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Table 2.3 Countries in each regional group, 1996–2014

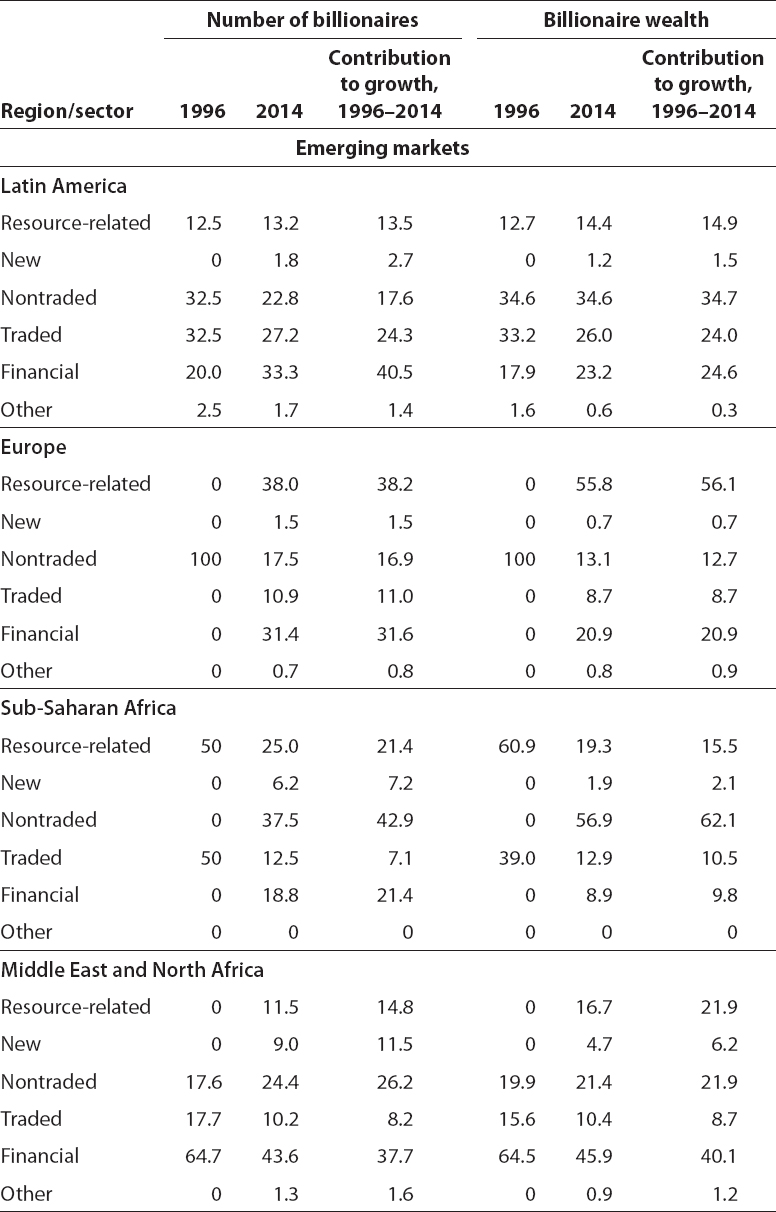

Table 2.2 (located on page 33) shows how billionaires and their wealth are distributed across sectors. In emerging markets, finance was responsible for 60 percent of billionaire wealth in 1996; by 2014 its share had fallen to 34 percent. In contrast, in the advanced countries, sectoral shares were relatively stable.

Regional Trends: From East Asia to Africa

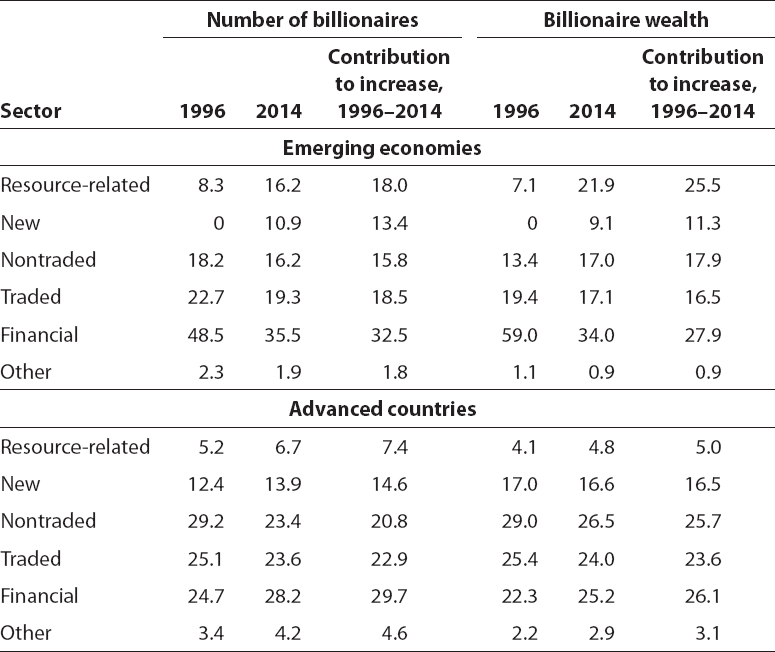

In 1996, 40 countries were represented on the billionaires list; by 2014 the figure had grown to 69. These billionaires come from one of seven regions: Europe (separated into high-income and emerging-market countries), Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, MENA, South and Central Asia, East Asia (separated into high-income and emerging-market countries), and Anglo countries (the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand). See table 2.3 for countries/economies included in each category. Billionaire wealth is concentrated in Europe, East Asia, and the Anglo countries (figure 2.2). Sub-Saharan Africa has the smallest share of total real billionaire net worth.

Within emerging markets, East Asian billionaires represent the largest group in terms of total real net worth, except between 2006 and 2008, when emerging Europe dominated. Following the global financial crisis, East Asian, Latin American, and European billionaire wealth rebounded quickly. In contrast, wealth in South and Central Asia and MENA stagnated or declined. Billionaire wealth in sub-Saharan Africa increased slightly after 2010.

Figure 2.2 Total real net worth of billionaires, by region, 1996–2014

Sources: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires; and World Bank, World Development Indicators.

East Asia: Land of Big Business

East Asian billionaires are by far the most dynamic group. Many Chinese billionaires have been able to take advantage of the large Chinese market for specific goods. Robin Li’s search engine, Baidu, for example, reaped more than 99 percent of its revenue within China in 2013. Some billionaires built their fortunes through trade, such as waste paper queen Cheung Yan, who imports recycled paper from the United States and turns it into packaging for Chinese exports. Others built their fortunes by bringing existing products to the region. The company owned by Indonesia’s Achmad Hamami, for example, controls the manufacturing and sale of Caterpillar equipment in Indonesia. Other entrepreneurs—such as Tony Tan, the founder of the Philippine fast-food restaurant Jollibee—created companies that serve local markets before expanding regionally.

Thanks to this new group of company founders, there has been an enormous shift in the countries and industries represented in the billionaire group. In terms of countries, billionaires from mainland Chinese are the big story. The Chinese moved from being unrepresented on the Forbes list in 1996 to making up more than 40 percent of East Asian billionaires in 2014. The rise of China is reflected in the change in the shares of inherited and self-made wealth. In 2001 more than 40 percent of East Asian billionaires inherited their fortunes; by 2014 the share of inheritors in emerging Asia had fallen to 12 percent (table 2.4).1

The other major change was in the financial sector. The Asian financial crisis of 1997 decimated many financial sector fortunes, replacing them with more diverse sources of wealth. In 1996 there were 69 emerging-market East Asian billionaires, 64 percent of them from countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand).2 By 2014 the share of ASEAN billionaires had dropped to less than half of the total in East Asia. New industries and tradables had replaced finance in emerging East Asia (table 2.5).

Latin America: Still High Levels of Inherited Wealth but Growing Shares of Innovators

Latin America is unique among emerging-market regions in beginning the period with over 60 percent of the billionaire population as inherited wealth. With a combined net worth of $12.5 billion, the six billionaire heirs to the Votorantim Group, which was founded as a textile factory in 1919 and later became the first Brazilian chemical company, reflect the importance of inherited wealth in Latin America.

But things are changing. By 2014 the inherited share had fallen to 49 percent (table 2.4). Inheritors are being replaced by Latin American innovators who have taken advantage of global markets to grow their companies. Brazilian Alexandre Grendene Bartelle is an example. His shoe company, Grendene, which produces low-cost footwear for both the domestic and international markets, is the world’s largest sandal maker. In Peru four of the five self-made billionaires on the 2014 list are company founders.

Table 2.4 Distribution of billionaires, by source of wealth and region, 2001 and 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Table 2.5 Distribution of number and wealth of billionaires, by sector and region, 1996 and 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

For Latin American billionaires, the nontraded sectors, particularly retail, media and telecommunications, and construction, initially captured the largest share of billionaire wealth, together accounting for about one-third of such wealth (table 2.5). Finance has taken over the lead over the last decade, while most other sectors have contributed to growth with roughly stable shares. One exception is the new sectors, which grew somewhat but still generated less than 2 percent of extreme wealth in 2014.

Brazil looks like the rest of Latin America, with high levels of inheritance, especially compared with the other BRICs (table 2.6). Founders and executives make up about one-third of all billionaires in Brazil, and their numbers are growing.

Emerging Europe: Home of the Self-Made Billionaire

High-income and emerging Europe diverge. Wealth in emerging Europe is steadily moving away from nontradables into other sectors. In contrast, high-income Europe has seen little change in the share of wealth in each sector over time (table 2.5).

The big difference is in inherited wealth (table 2.4). There are no family dynasties in emerging Europe. In contrast, wealth in old Europe is largely old money. Europe as a whole is divided about evenly between self-made and inherited wealth. Emerging Europe is dominated by resource rents, but like other emerging markets there is rapid growth in the number of company founders.

Table 2.6 Sources of wealth of billionaires in BRIC countries, 2001 and 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Many billionaires in emerging Europe were able to take advantage of the wave of privatization following the fall of the Soviet Union. Ukraine’s president, Petro Poroshenko, built his confectionery empire by first creating a small private company and then acquiring cheap Soviet candy factories. Others took advantage of the transition as first movers in new sectors. Entrepreneur Zygmunt Solorz-Zak benefited from the transformation of the media sector, establishing one of the first private television companies in Poland.

Russia has more resource-related/politically connected wealth than any of the other BRICs (table 2.6). As the oil magnate Vladimir Yevtushenkov commented, “The size of your business should be matched by the size of your political influence. If your political influence is smaller than your business, it will be taken away from you. If your political influence is bigger than your business, then you are a politician.”3 Founders still represent a small share of Russian billionaires, but their numbers grew markedly in the 2000s. Outside Russia the number of billionaires in emerging Europe is now roughly evenly split among resource- and privatization-related billionaires, financial-sector billionaires, and founders.

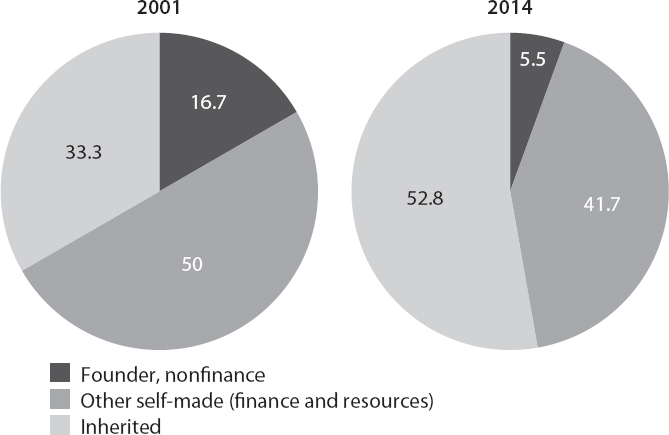

Figure 2.3 Sources of wealth of Arab billionaires, 2001 and 2014 (percent)

Note: All Forbes data exclude royals.

Source: Data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Middle East and North Africa: Growing Shares of Inherited Wealth, Declining Entrepreneurship

MENA is the only emerging-market region in which the share of inherited wealth has increased over time and the share of founders decreased. Self-made MENA billionaires are highly dependent on resource-related and politically connected wealth. Table 2.4 overstates company founders, because Turkey and Israel, two outliers, are included in MENA.4 Excluding them, the share of founders falls to less than 6 percent in 2014, one-third of the share in 2001 (figure 2.3).

Something in the region, especially the Arabic-speaking part, is preventing large private companies from thriving. With more than 300 million native Arabic speakers, it is surprising that there is not a single computer industry billionaire. (China and India have many, and the founder of Yandex, Russia’s largest search engine, is a billionaire despite a much smaller Russian-speaking population.) There are only two Arab billionaires in consumer tradables. One is Prince Sultan bin Mohammed bin Saud Al Kabeer, whose company, Almarai, produces dairy in the desert—hardly a business based on comparative advantage. The other is Algeria’s only billionaire, Issad Rebrab, a teacher before he switched to business in the 1970s and founded Cevital, now Algeria’s largest sugar exporter. In the rest of MENA, the ranks of the superrich are populated by the second or third generations of wealthy families like the Hariris of Lebanon and the Mansours and Sawiris of Egypt. Businessmen and -women from the region have done extremely well in other parts of the world, indicating that the issue is not people but the climate for investment and commerce in the region. The most well-known is Mo Ibrahim, born in Sudan and now a British citizen, who started the African mobile phone company Celtel, which had tens of millions of subscribers when he sold for $3.5 billion. Nicolas Hayek, of Lebanon, was a cofounder of the phenomenally successful company Swatch. This was Hayek’s second highly productive venture in Switzerland, the first was Hayek Engineering, a prosperous management consulting firm. The Syrian-born French entrepreneur Mohed Altrad turned a bankrupt scaffolding company into a billion-dollar one. Having grown up Bedouin in the desert of Syria, his story is one of rags to riches, after receiving a scholarship to study abroad.

The sectors responsible for wealth in MENA have also changed little over time: Finance and nontradables continue to drive wealth, very little of which is generated by new sectors or tradables. These sectors are concentrated in Israel and Turkey. Resources show up only in the later years, not because they were not important in prior years but because resource wealth has traditionally been confined to the ruling class, who by construction are not included in the Forbes data.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Showing Signs of Change

Resource-related wealth dominated the period 1996–2011 in sub-Saharan Africa. But in recent years traded sector wealth, spurred in large part by the fortune of Nigerian tycoon Aliko Dangote, surpassed resource-related wealth, as Dangote transformed his trading company into a producer of flour, sugar, and cement that operates throughout West Africa.

South Africa is home to half of the billionaires of the region, with all of the region’s inherited wealth and nearly 40 percent of self-made wealth. Billionaires from other countries (including Angola, Nigeria, Swaziland, Tanzania, and Uganda) tend to be founders and company executives.

South Asia: Innovation in India, Resource- and Government-Related Wealth Elsewhere in the Region

Resources remain an important source of wealth in South Asia. By 2014, however, new industries made up a larger share of wealth than resource-related industries, driven by falling commodity prices and the rise of Indian computer and pharmaceutical billionaires.5 The two sectors each account for about 40 percent of billionaire wealth. Four of the six founders of Infosys, an Indian company that creates software and provides information technology services primarily for the banking sector, were on the billionaires list in 2014. A complex program of allocating resource permits in India has also allowed the rise of rent-related resource billionaires.

Outside India, Nepal’s Binod Chaudhary is the only billionaire in the region not connected to resources or the government. Chaudhary turned his father’s department store, the first in Nepal, into an international conglomerate by marketing products, such as its popular instant noodles, regionally rather than exclusively for his small home market.

Takeaways

Sources of wealth differ across the emerging-market world. East Asia is the most dynamic emerging region, with an enormous amount of self-made wealth, most of which is accruing to company founders. Latin America has large shares of inherited wealth relative to the rest of the world. Emerging European countries (particularly Russia) have high levels of politically connected wealth. In Latin America, MENA, emerging Europe, and South Asia, resource-related sectors and political connections remain important, although except in MENA and South Asia, the share of rentiers is on the decline and the share of company founders growing.

1. China had a single billionaire in 2001, Rong Yiren, former vice president and founder of state-owned investment corporation CITIC Group.

2. The remaining third were from Taiwan and Hong Kong.

3. “Billionaire Placed under House Arrest in Russia,” New York Times, September 18, 2014.

4. Israel is included in emerging markets because it was not a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) until 2010. Including it in the advanced-country group does not significantly affect any of the results, with the exception of MENA region aggregates, as discussed in this section.

5. Aditi Gandhi and Michael Walton (2012) note this trend in Indian billionaire wealth using Forbes data through 2012. The analysis in this book is consistent with their findings, revealing the continued decrease in the influence of rent seekers among Indian billionaires.