A Few Good Women

Zhou Qunfei grew up poor in Hunan Province, where she worked on her family’s farm to help support her family. Later, while working at a factory in Guangdong Province, she took business and computer courses at Shenzhen University. She started a company with money she saved working for a watch producer. In 2015 she was the world’s richest self-made woman, with a fortune of $5.3 billion, according to Forbes. Her wealth comes from her company, Lens Technology, which makes touchscreens. It employs 60,000 people and has a market capitalization of nearly $12 billion.

Lei Jufang was born in Gansu Province, one of the poorest areas of northwest China. After studying physics at Jiao Tong University, she created a new method for vacuum packaging food and drugs, which won her acclaim as an assistant professor. On a trip to Tibet she became fascinated by herbal medicines. In 1995 she founded a drug company, Cheezheng Tibetan Medicine, harnessing her skill in physics and engineering to exploit the untapped market for Tibetan medicine. Her company has a research institute and three factories that produce herbal healing products for consumers in China, Malaysia, Singapore, and North and South America. She has amassed a fortune of $1.5 billion.

In most countries, women get rich by inheriting money. China is different: The majority of its women billionaires are self-made. Zhou Qunfei and Lei Jufang are unusual because they established their own companies. Most of the eight Chinese female self-made company founders worth more than $1 billion made their money in real estate or in companies founded jointly with husbands or brothers.

Women made up less than 3 percent of all self-made billionaires in emerging markets in 2014. Of the five richest women in these markets—Iris Fontbona, Yang Huiyan, Eva Gonda Rivera, Pansy Ho, and Chan Laiwa—four inherited their fortunes. Two are from Latin America (Chile and Mexico), two from Mainland China, and one from Hong Kong. The fifth-richest, Chan Laiwa, is the founder of the Chinese real estate company Fu Wah International Group.

Self-made female billionaires are equally scarce in advanced countries, where women also account for less than 3 percent of the total. All five of the richest women from advanced countries—Christy Walton, Liliane Bettencourt, Alice Walton, Jacqueline Mars, and Gina Rinehart—inherited their fortunes, although Rinehart, the Australian mining magnate, heads her company and expanded her fortune dramatically.

The Amazing Women of China and the United States

Of the 38 female self-made billionaires in the world in 2014, 16 are from the United States (3.2 percent of all self-made billionaires there) and 8 are from China (5.2 percent of all self-made billionaires there). The United Kingdom is home to three, and Hong Kong has two. Angola, Brazil, Italy, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Macau, Nigeria, and Russia each have one. In 2001 only three women, all from advanced economies, were self-made billionaires.

These women are not as rich as their male counterparts. In emerging markets their average net worth is $1.1 billion less than that of self-made men; in advanced countries the difference is even larger ($1.7 billion).

The share of female billionaires in the North is about twice the share in the South, and the size of both groups roughly doubled in 2001–14 (table 7.1). The share of female self-made billionaires in emerging markets is about the same as in advanced countries. In both regions the share of inherited wealth among women increased between 2001 and 2014. Women remain grossly underrepresented in all categories of billionaires.

Sectors of Self-Made Women

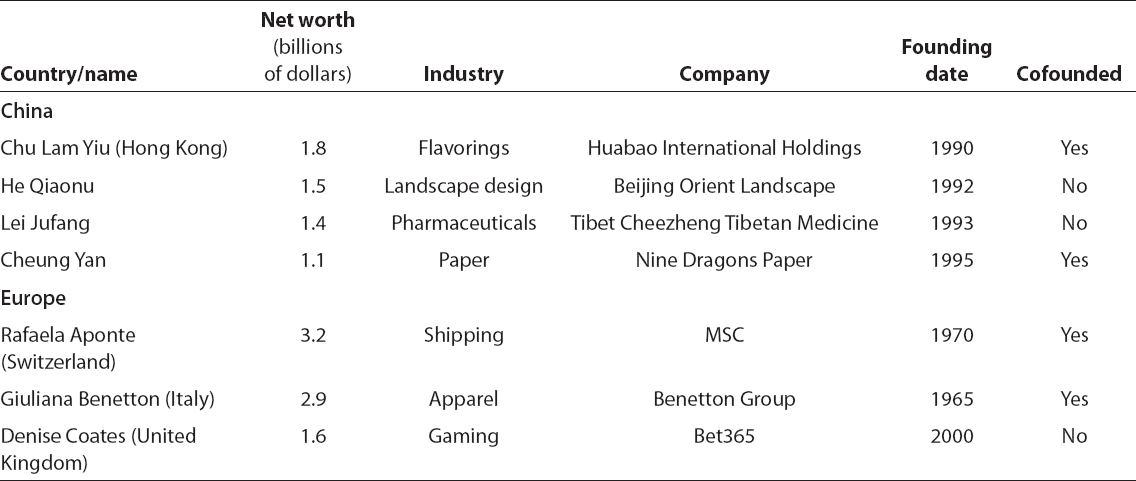

Half of all self-made billionaire women in emerging markets made their money in the financial sector. This figure is significantly larger than the figure for men (35 percent) (table 7.2). In contrast, in the North women are underrepresented in the financial sector. The difference may be in part because finance in the South is primarily real estate, while in the North it is investment banking and hedge funds. In both the traded and nontraded sectors, women tend to be more prevalent in areas traditionally associated with them, such as fashion and health care, and tend to be less prevalent in areas requiring heavy startup investments, such as machinery. In both the North and the South, women underperform in the resource sector. Resource wealth is typically connected to the government (which grants rights and permits), suggesting that women may be excluded from certain networks. The list of company founders includes only 19 women who are not in finance or politically connected (12 in the United States, 4 in China, and 3 in Europe) (table 7.3). Even within this elite group, the vast majority started their companies with their husbands or brothers. Only six founded their companies alone.

Table 7.1 Distribution of male and female billionaires and their wealth in advanced countries and emerging markets, 2001 and 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Author’s classification based on data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Table 7.2 Source of wealth of male and female self-made billionaires in advanced countries and emerging markets, 2014 (percent of total)

Source: Author’s classification based on data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Why Are There So Few Self-Made Billionaire Women?

One reason there are so few women billionaires may be that a woman needs to persevere more to break into a new business because of discrimination or exclusion at all levels of product development. The story of American billionaire Sara Blakely, the founder of Spanx, which makes women’s undergarments, highlights the constraints women face. Blakely cut off the legs of her pantyhose to achieve a smoother look under pants while still being able to wear open-toed shoes. Other women had probably done this before, but she recognized that the idea was marketable and acted on it. She spent two years developing the product, which she brought to market while working a day job. She stayed engaged with all aspects of the business, even moving the placement of the product in department stores to ensure sales. Her big break came when another female billionaire, Oprah Winfrey, identified Spanx as a favorite product. Blakely financed development largely from retained earnings. To this day she owns 100 percent of the company.

Table 7.3 Companies founded or cofounded by women who became billionaires, by region, 2014

Note: List excludes women who made their fortune in finance or through political connections.

Source: Author’s classification based on data from Forbes, The World’s Billionaires.

Three features of this story stand out: innovation and perseverance, a lucky break with an important business connection that yields access to potential customers, and very limited financing. These features are common to the stories of many women billionaires.

Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, India’s only self-made female billionaire, also experienced a lucky break. After struggling to find a position as a brewmaster in the traditionally male-dominated brewing industry in India, she met an Irish entrepreneur looking to bring biotech to India, who persuaded her to switch from beer to enzyme production. Her first outside investment was granted at a social event, after banks refused to loan money.

The more business connections a person has, the more likely he or she is to get that lucky break. Women tend to have fewer links with industrial counterparts than men. Across countries they are less prevalent in the C-suite and corporate boards and outnumbered in industrial organizations, and only a small number hold top government positions, especially in business-related areas (Kotschwar and Moran 2015).

Paul Gompers et al. (2014) study female venture capitalists (VCs) to highlight the importance of networks. They show that male VCs benefit from successful colleagues but female VCs do not if their colleagues are all male (as is often the case). Women significantly underperform male colleagues with similar characteristics, but the performance gap is due to the quality of a man’s male colleagues. The authors’ interviews indicate that women do not participate in informal meetings and social activities to the same extent as men. As one woman commented, “There are many events for VCs…that don’t include women. Fly fishing, car racing, golf, etc.—no women.” Another VC noted that she was “often inadvertently excluded from a variety of social gatherings, including guys’ weekends.” This networking effect, which is very important in the financial sector, may help explain why so few women made their fortunes in finance (outside of real estate) and why women entrepreneurs have a harder time accessing finance.

Difficulty obtaining financing means that companies must grow first, before or without ever receiving the large financial backing typically needed to turn a company into a global powerhouse. Financing is also important for growth, especially in industries where startup costs are high. Research shows that external financing is less available to women even in the United States. According to the Diana Project, which studies women’s entrepreneurship, “while the rate of women’s participation in new venture creation around the world was at an all-time high during the 1990s, their ability to grow their companies by accessing equity capital was extremely limited. Nearly 20 percent of the IPOs brought to market from 1995–1998 were women-owned or managed firms, providing evidence of women’s ability to lead high-growth, high-value firms, yet only 2 percent of these were venture funded” (Brush et al. 2004, 2). A wealth of studies from the World Bank, summarized in its Gender at Work report (2014), shows that women entrepreneurs in developing countries tend to be especially underserved by the financial sector.

The problem with obtaining finance for a new enterprise is in part associated with the small number of female investors. Only 6 percent of VCs in the United States are women and nearly 80 percent of firms have never had a female investor (Gompers et al. 2014).

Why Is China Different?

China’s relative success in female entrepreneurship is credited to a number of factors. One is culture: In China, unlike many other developing countries, women are expected to work outside the home. Like in the United States, women make up nearly half of the labor force; the ratio of women’s participation to men’s participation is 82 percent in both countries, according to the World Bank (2012). There are also more opportunities for innovative women like Lei Jufang because of growth and modernization. In addition, most private firms in China grow through retained earnings (Lardy 2014), so competition from well-financed firms is less intense.

Importance of Female Entrepreneurs for Resource Allocation

The problem of the dearth of female entrepreneurs goes beyond equity: The small number of female mega firm founders implies that some great ideas are not being exploited. Discrimination is not just a problem for the people it directly affects; it hurts the economy as a whole. There is no reason to think that half of the population has less than 3 percent of the best business ideas. The fact that women have a harder time joining business networks and finding financing makes it harder for them to grow their companies. Worse still, it discourages other women from even trying to start a business. If women were part of business networks and had equal access to finance, there would very likely be more new businesses, more competition, and a better allocation of capital. Indeed, the two countries with the most women on the list, the United States and China, are arguably the best-performing countries in their income brackets. Raising hurdles for female entrepreneurs lowers the bar for potential firm growth, reducing job opportunities.

An encouraging sign for future growth is that women who strike it rich often help other women. US billionaire women Tory Burch and Sara Blakely owe their success to the most famous American female billionaire, Oprah Winfrey. Her endorsement of their products marked the turning points in growth for their companies, highlighting the importance of business networks. Winfrey is helping women in many other ways as well, and not just in the United States. Her foundation focuses on girls in South Africa.

Burch and Blakely are following her lead. Both the Tory Burch Foundation and Leg Up (Blakely’s foundation) support women entrepreneurs through loans and training. Sheryl Sandberg, the second-most famous American female billionaire, is also interested in women’s issues. Her bestseller, Lean In, is about what women can do for themselves to improve chances of career promotion and business success and also the gains from company and country policies that encourage leadership in women.

Outside the United States, many women who have made large fortunes contribute to causes that support women and children. Folorunsho Alakija, Nigeria’s richest woman, created the Rose of Sharon Foundation, which provides widows and orphans with business grants and scholarships. Lei Jufang has set up schools in Tibet that train students, mostly from poor backgrounds, to be doctors. Giuliana Benetton and her siblings have created a charity to help children in war-torn areas. J. K. Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter series, contributed so much of her fortune to charities to help women and children that she dropped off the Forbes World’s Billionaires List in 2012.

Why Do Women Inherit Less Than Men?

Women represent a relatively small share of inherited wealth—less than a third of the spots for heirs in both the North and the South. Their underrepresentation may reflect a preference for passing wealth on to male relatives.

Some family fortunes have been divided equally. Patricia and Roberto Angelini Rossi cochair the Angelini Group. The three billionaire children of Samsung chair Lee Kun-Hee all have leadership roles in the company (though only his son has been groomed to take his position). Catherine Lozick’s father left her, not her brother, the majority stake in his water valve company (Swagelok). Globally, however, less than 30 percent of inherited billionaires are female, suggesting that either parents leave larger shares of their fortunes to their sons or men are more likely to grow or maintain a large inheritance (the significantly larger number of self-made male billionaires is consistent with the notion that men are more successful than women at expanding fortunes).

But there is evidence that daughters are often shortshrifted when it comes to inheritance. In countries with at least five inherited fortunes, Egypt, Singapore, and Taiwan report none accruing to women, and Canada, the United Kingdom, and Italy record female inherited wealth at 15 percent or less of total inherited wealth. Studies of family businesses in countries as different as Denmark and Thailand show strong evidence of bias toward passing on ownership to men over women (Bennedsen, Pérez-González, and Wolfenzon 2007; Bertrand et al. 2008).

Takeaways

Large-scale entrepreneurship among women is extremely rare. The United States and China have performed the best, but even in these countries there are more than nine self-made male billionaires for every female one.

Weaker business networks and limited access to financing help explain the small share of women leading large businesses. Women have tended to grow companies in areas with large shares of female consumers, such as fashion, food, health care, and services, where networks for female entrepreneurs are stronger and significant financing is not a requirement to start up. In contrast, there are no female company founders in machinery, electronics, or hedge funds.

The absence of women is not just bad from an equitable distribution perspective. It has implications for resource allocation—the theme of this book. A great deal of talent appears to be going to waste. The higher bars that women have to jump over to grow businesses mean that some great ideas are not being transformed into mega firms and economic growth.