Chapter 6

THE CONSORT OF THE YOGIN:

South Asian Siddha Cults and Traditions

1. Siddha Demigods and Their Human Emulators in Medieval India

In chapter 4 we evoked the metaphysical explanation for the relationship between human Kaula practitioners and the supernatural beings with whom they transacted in their practice: the semidivine Siddhas and Yogins inhabit the bodies of selected human Kaula practitioners in order to “spontaneously sport with one another.”1 In the preceding chapter, we described the narrative appropriation of the same principal: Prince Naravhanadatta is a “fallen” Vidydhara who rediscovers his inherent demigod status through his karmically determined encounters with Vidydhar women who have similarly fallen into human rebirths. Once these figures recover the knowledge of their past lives, a carnal knowledge, they return to their semidivine station and become the kings and queens of the firmament that they had been before their fall.2 Naravhanadatta is also a prince, whose elevation to a prior or innate semidivine station coincides with his realization of the status of universal conqueror, cakravartin. What these sources make clear is that, regardless of the innate power of the Yogin, the prime Tantric actors in South Asia have always been male, and the historical record of Tantric practice, in literature, architecture, and the arts, has always been told through the eyes of a male protagonist, who sought or claimed for himself the status of Virile Hero or Perfected Being. We now trace the history of these beings in South Asian traditions.

Since at least the time of the Hindu epics, cults of a group of demigods known as the Siddhas have figured in the pantheons of South Asian Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains alike. These beings form the cast of thousands in the pageant of heaven: whenever a hero performs some great deed or travels to the atmospheric regions, a host of Siddhas, Vidydharas (Wizards), and Craas (Coursers)3 sings his praises and showers him with flowers. Who were the semidivine Siddhas? Already in the time of the Epics, they were (and in some cases they remain) the object of popular cults. The Amarakoa, a fifth-century lexicon, classes them—together with the Vidydharas, Yakas, Apsarasas, Rkasas, Kinnaras, Gandharvas, Picas, Guhyakas, and Bhtas—as devayonaya, demigods “born from a divine womb” and therefore not subject to death.4 Over time the notion arose that the realm or level of the Siddhas was one to which humans, too, could accede, and so it was that in the course of the medieval period, a growing pool of “human” Siddhas and an expanding body of Siddha legend came to be constituted.5 With the emergence of the Kaula, the semidivine Siddhas became associated with the Yogins, their female counterparts of the atmospheric regions. These latter, too, had their human emulators, called Yogins or Dts, and the origins of Tantra are intimately entwined with the ritual interactions of these self-made gods and goddesses. Beings called Siddhas—now identified as demigods, now as human virtuosi who become possessed by the same—also play important roles in the popular religion of western India. In this chapter I will trace the religious history of the Siddhas, from their lofty origins at the cope of heaven or the tops of distant mountains, to their identification with human practitioners whose greatest aspiration was, precisely, to fly to the realm of their semidivine role models, and, finally, to their internalization within the yogic body of those same human practitioners.

While the hills of central India are dotted with the ruins of Yogin temples from the early medieval period, there is not a single edifice on the subcontinent that one could qualify as a “Siddha temple” in the sense of a temple to the Siddhas (although a handful of temples to iva Siddhevara, “Lord of the Siddhas,” did exist in the medieval period).6 Despite this, it is nonetheless the consort of the Yogin, the male Siddha, who is the heroic “protagonist” of much of the literature of the period, both secular and sacred. The various Kaula and Tantric liturgies are always described from the perspective of the male practitioner, who, in addition to being termed the “Son of the Clan” or the “Virile Hero,” is also often referred to as a Perfected Being in a lineage of Perfected Beings going back to the founders of the various Kaula lineages. These lineages, as we have seen, constitute the “flow of gnosis” (jñna-pravha), whose initiates, “conversant in the secret signs and meeting places of the various lineages . . . range among the phas,” to receive initiations and supernatural empowerments from the mouths of Yogins.7

The fourteenth- to fifteenth-century akaravijaya of nandagiri,8 which devotes its forty-ninth chapter to a description of the Siddhas, clearly demonstrates the power-based nature of these traditions:

Then the Siddha practitioners Cirakrti, Nitynanda, Parrjuna, etc., came together and said to the Swami [akarcrya], “Hey Swami!

“Our own doctrine is based on what is manifestly real. It is, to be sure, a highly multifaceted doctrine that flows from the diverse nature of our Siddha practices. Here, by means of the complete perfection of mantras obtained through the Siddha teachings, we have realized our goals and are eternally free. . . .

“Having gained possession of special herbs and mantras at Srisailam and other lofty sites where divine beings make themselves visible, Satyantha and others became Siddhas, persons who had realized their goal and long life. We are of the same sort [as they, living] according to their [Siddha] precepts. The entire expanding universe is fully known to us.

“Through our special knowledge of [various powers of sorcery], and our special expertise in gaining mastery over [each of the five elements], and by virtue of drinking poisons, drinking mercury, and drinking [specially prepared] oils . . . [and] by means of special forms of yogic practice, [we effect] the removal of accidental or untimely death. By means of special [acts of] sorcery (kriy) . . . through special aktis . . . Yakis . . . [and] Mohins, by means of the various divisions of Kak[y]apua knowledge, iron-making, copper-making, silver-making, gold-making, etc., by means of various types of metallurgical expertise . . . [and] through the special use of black mercuric oxide, roots, and mantras, magic and great magic, we can strike people blind and bind lions, arabhas, and tigers. By means of this panoply of specialized practices, we are, in fact, omniscient.”

In this precious text, we find not only clear evidence for the scope of the medieval Siddha traditions, but also early references to specific centers for Siddha practice (Srisailam),9 Siddha literature (Kak[y]apua),10 and Siddha practitioners (Nitynanda, Satyantha, Cirakrti, Parrjuna).11 It also brings into focus what one may call the “Siddha distinction,” as such has been defined by the great Tantric practitioner-scholar Gopinath Kaviraj: “Some . . . were accomplished (siddha) in the alchemical path (rasamrga), some accomplished in haha yoga, and still others had perfected themselves through Tantric practices or through the use of sexual fluids (bindu-sdhan).”12 To these we might add sorcery that generally involved the use of mantras to conjure and control powerful female entities—the aktis, Yakis, and Mohins mentioned in this passage. The guiding principle here seems to have been one of controlling a universe that was understood to be a body, the body of the divine consort of iva, the body of one’s own consort, the feminine in one’s own body, and the embodied universe.

2. Siddhas and Yogins in the Kaulajñnaniraya

Some of my discussion of the Siddhas in this chapter revisits matters discussed in The Alchemical Body, and the reader is invited to consult that work for further data on the Nth Siddhas in particular. There was, however, another important sectarian offshoot of the earlier mythological, cosmological, and soteriological Siddha traditions: this was the Siddha Kaula, the Kaula sect of which Matsyendra(ntha) was an adherent if not the legendary founder. With the Siddha Kaula, we perhaps find ourselves in the presence of the earliest group of Indian practitioners seeking to identify themselves with the demigod Siddhas. A ninth- to tenth-century account of them, found in the Mgendrgama, juxtaposes them with a number of other groups, whose ontological statuses are equally ambiguous:

The sages know of eight [other] currents, connected respectively to iva, the Mantrevaras, the Gaas, Gods, Ris, Guhyas, the Yogin Kaula and the Siddha Kaula. . . . The Yogins received a wisdom that immediately causes yoga to shine forth. It was called Yogin Kaula because it never went beyond the limits of their circle. The same is the case for the other [i.e., the Siddha Kaula current].13

In fact, the Yogins’ wisdom did go beyond the limits of their circle, and it was Matsyendra, precisely, who is held to have been responsible for this development. This is the subject of the KJñN mythology of the theft and recovery of the Kaula scriptures, discussed in chapter 4. As we also have shown, it is for his fusion of the Siddha Kaula with the Yogin Kaula that Matsyendra is venerated by the great Abhinavagupta in the opening lines of his T. Matsyendra’s pivotal role in the history of Hindu Tantra has been described by Alexis Sanderson:

The distinction between Kula and Kaula traditions . . . is best taken to refer to the clan-structured tradition of the cremation-grounds seen in the Brahmaymala-Picumata, Jayadratha Ymala, Tantrasadbhva, Siddhayogevarmata Tantra, etc. (with its Kplika kaulik vidhaya) on the one hand and on the other its reformation and domestication through the banning of mortuary and all sect-identifying signs (vyaktaligat), generally associated with Macchanda/Matsyendra.14

A reference to the Kaula practitioner’s concealment of sectarian marks (guptaligin) is found in chapter 22 of the KJñN, which groups the Siddhas together with the deities who are receiving the oral teachings of Bhairava.15 Chapter 9 of the same work presents the various categories of Kaula practitioners, in which the text’s divine revealer Bhairava states:

I will describe the array of the assemblies of the preceptors, Siddhas and Yogins . . . [as well as] the entire group of Airborne (Khecar) Mothers of all the Siddhas and Yogins [and] the entire group of Lords of the Fields16 [present at] the dwellings of all the Land-based (Bhcar) Yogins. All of the Mantra-born, Yoga-born, Mound-born, Innately-born, and Clan-born [beings, as well as] all of the Door Guardians and all of the Womb-born Yogins and Siddhas17 are worshiped in different ways in the four ages—in the Kta, Dvpara, Treta and greatly afflicted Kali age.18

Then, following a list of eighteen Siddhas and five Yogins that are to be worshiped, the chapter goes on to give the following mytho-historical account of the Siddhas:

One first makes the [utterance] hr, followed by r. One should place the display of this pair of syllables beyond the boundary [of the mandala].19 The one [represents] the Siddhas and [the other] the Yogins, [who taken together constitute] the perfected beings. . . . There has never been such a Gnosis as this, and there never will be. In [this], the most terrifying, exceedingly fearsome and savage Kali age, the sixteen Siddhas are well known. In the Kta, Dvpara and Treta, they are worshiped as Virile Heroes. [These are the Siddhas called the] Mipdas, Avatrapdas, Sryapdas, Dyutipdas, Omapdas, Vyghrapdas, Hariipdas, Pañcaikhapdas, Komalapdas and Lambodarapdas.20 These are the first great Siddhas, those who brought the Kula and the Kaula down [to earth]. In each of the four ages, these are the ones who animate the independent Clan. Through the power of knowledge of this [Clan], many are the men who have become perfected. This Kaula has an extension of ten kois beyond the world of existence.21

The balance of chapter 9 recounts the transmission of the highest essence of the Mahkaula through a series of exclusively female deities, from “the Yogin called Icch(-akti) by the Siddhas” down through the Airborne Mothers, and the Land-based Yogins. The chapter concludes with the promise that the mortal (male) practitioner who receives this gnosis (jñna) shall obtain enjoyment (bhukti), liberation (mukti), and supernatural power (siddhi), and become the beloved of the Yogins.22 The source of this transmission is detailed in the second chapter of the KJñN, entitled “Emission and Retraction,” in which the relationship between iva and akti in her three forms is shown to be a circular or cyclical one: “akti is gone into the midst of iva; iva is situated in the midst of Kriy [-akti]; Kriy[-akti] is absorbed into the midst of Jñna[-akti]; [and] Jñna[-akti]23 is absorbed by Icch[-akti]. Icch[-akti] goes to the state of absorption there where the transcendent iva [shines in his] effulgence.” The importance of this dynamic is underscored in the final verse of this chapter: “The foundation of the Clan [as regulated] by [the cycle of] emission and retraction has been briefly described.”24

The classes of Siddhas and Yogins mentioned in passing in chapter 9 of the KJñN are described in greater detail in the preceding chapter,25 which opens with an account of six types of aktis, known as “Field-born,” “Mound-born,” “Yoga-born,” “Mantra-born,” “Innately-born,” and “Clanborn.” The Kaula practitioner is instructed to practice, together with the last two of these—along with another type of akti, the “Lowest-born”—in an isolated, uninhabited spot, using flowers, incense, fish, meat, and other offerings.26 Here, the term “Lowest-born” refers to an outcaste woman; a married woman is called “Innately-born,” and a prostitute is called “Clan-born.”27 Three of these are stationed within the body, while three are external.28

Following this, a sexual ritual involving the Kaula practitioner and a “Lowest-born” woman is described: their conjoined sexual fluids, placed in a set of two vessels (yugmaptra), are offered to the sixty-four Yogins and the fifty-eight Vras, “all [of them] clad in blood[-red] garments, and effulgent with armlets and bracelets of gold.”29 Next the text evokes the worship of the great Field-born Yogins and Siddhas, together with the great Goddess, at the eight Indian cities or shrines of Karavra (Karnataka, western Deccan), Mahkla (Ujjain), Devkoa (Bengal), Varanasi, Prayaga, Caritra-Ekmraka (Bhubanesvar), Aahsa (Bengal?), and Jayant.30 A number of Hindu and Buddhist Tantric works present similar lists of centers of Yogin and Kaula worship, lists that appear to indicate the geographical parameters of Kaula practice in the early medieval period. These would have been the sites at which male Virile Heroes and female Yogins would have met on specified nights of the lunar calendar to observe the Kaula melakas and other rites.

Associated with these because they were born at and preside over these sites are sixteen “Field-born” male Siddhas. This is the first of six groups of Siddhas, which correspond to six types of aktis.31 Hereafter, the KJñN enumerates four Mounds (phas)—Kmkhy, Pragiri, Uiyna, and Arvuda32—each of which comprises numerous secondary mounds (upaphas), fields, and secondary fields (upaketras). Then, stating that it will provide instructions for worship of these and their divinities, the text offers a second list, this time of sixteen Mound-born Siddhas who were born at these sites.33 The Siddhas who became perfected (siddha) through the practice of yoga are called “Yoga-born”; those who propitiate [with] mantras are “Mantra-born.”34 Next, referring to a well-known Puranic myth of the Goddess’s defeat of the demon Ruru at Blue Mountain (usually identified with Kmkhy), the text explains the origins of the “Innately-born” Siddhas.35 Hereafter, eight goddesses—many of whose names correspond to the classical listing of the Seven Mothers—are listed as the “Pervading Mothers.”36 Also mentioned are the female Door Guardians. All of these, the text states, are to be worshiped, together with their retinues of Siddha preceptors, in every town and city.37

Chapter 20 of the KJñN gives another account of these same actors, with certain variations in terminology. It begins by making a distinction between the Clan aktis and Virile Heroes and “another akti,” Icchakti, already identified in chapter 9 as the supreme Goddess. Following this, the Goddess, saying that Jñn-akti is already known to her, asks the narrator Bhairava to give an account of Kriy-akti.38 In answer, the text gives a description of the akti of the Virile Hero—that is, the human consort of the male practitioner—such as is found in dozens of Tantric descriptions (her Buddhist homologue would be the “Karma-Mudr”). This is followed by that of her counterpart, the Virile Hero, described in equally idealized terms. Both are clearly human figures, possessed of the requisite physical, emotional, and mental qualities for admission into and participation in Clan ritual.39 Chapter 11 of the KJñN gives additional data, listing the kulasamay[in] (“pledge”), kulaputra (“son of the clan”), and sdhaka (“master”) levels of initiation. These appear to correspond to the standard terminology, found in the gamas of the aivasiddhnta, for ascetics having undergone the three successive initiations known as samayin, putra, and sdhaka. Other inferior levels of initiation described in various Tantric sources include the miraka, the “mixed” initiate, and the daiva (“divine”) category of initiate: both refer to the occasional practitioner, the householder who temporarily ventures into the ritual circle of Tantric practice, to return to his household and householder lifestyle at the end of the ritual period.40

Most of the data found in these three chapters of the KJñN concern entities named Mothers, aktis, Yogins, Vras, and Siddhas. Among these, the females entities are located both within and outside the body, with the latter being identified with—or incarnating in—different types of human women. More often than not, the males appear to be human, born at different locations identifiable as cities, mountains, temples, or shrines situated on the territory of the Indian subcontinent. However, both Siddhas and Vras are objects of (often internal) worship in this text,41 an indication that some if not all of these had raised themselves to divine or semi-divine status through their practice, through their interactions with females identified as goddesses, in earlier ages. This, precisely, is the major innovation of the medieval Siddha traditions. Whereas the Siddhas were in earlier mythological, cosmological, and soteriological traditions superhuman demigods who had never entered a human womb, the Siddhas of the Kaula clans were humans who, through their practice, acceded to semi-divine status and the power of atmospheric flight. At a still later stage, they were also internalized, to become objects of worship within the bodies of male initiates, who also called themselves Siddhas or Vras. We will discuss the process of their internalization later in this chapter, and the internalization of the Yogin in chapter 8.

3. Siddhas as Mountain Gods in Indian Religious Literature

Well before the KJñN and other Kaula works, the place of the Siddhas whom human practitioners emulated and venerated had long been established in the mythology, symbol systems, and “systematic geography”42 of the subcontinent. Generally speaking, Hindu, Jain, and to a lesser extent Buddhist sources offer three primary venues as the abodes of the semidivine Siddhas: atop mountains located near either the center or the periphery of the terrestrial disk (Bhloka); in atmospheric regions above the sphere of heaven (Svarloka); and at the summit of the cosmic egg, at the level variously known as Brahmaloka, Satyaloka, or Siddhaloka.

The first of these venues appears to be the earliest and the most widely attested. In fact, certain of the high gods of Hinduism were identified, early on, as mountains. In Tamil traditions, Muruka is the “Lord of the Mountains” (malaikiav), more closely identified with the “mountain landscape” than with the son of iva in the sagam literature. Similarly, Govardhana, the mountain of Ka mythology, was worshiped as a mountain in its own right before being incorporated, relatively late, into the cult of that god. Moreover, it continues to be worshiped as a mountain today by the tribal inhabitants of Braj, independent of its associations with Ka.43 Before the many strands of his earlier traditions coalesced into the familiar elephant-headed form in which he has been worshiped for centuries, Gaea, too, had his origins in mountain cults of the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. Going back to Epic traditions, we find the mountain-dwelling iva wedded to Prvat (“Mountain Girl”), the daughter of Himavn (“Himalaya”); still earlier, the RV characterizes all mountains as supernatural beings, possessed of the power of flight, until Indra, the king of the gods, clips their wings!44

In western India in particular, one encounters very early traditions of (1) a god named rnth, Nthj, Jlandharnth, Siddhevara,45 and so on; (2) a grouping of semidivine figures, known as the Siddhas, who frequent the upper levels of the atmosphere, below the heaven of the gods, but who also walk the earth in human guise;46 and (3) a group of deities known as the Nine Nths (navantha), who originally had nothing to do with the historical Nth Siddhas and their legendary histories of the nine founders of their order. Quite often, these divine Nths were identified as mountains: the mountain itself was named either “Nth” or “Siddha.” This tradition of identifying mountains as divine Nths or Siddhas is one that also continues down to the present day in Maharashtra, Nepal, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh.47 However, even after the advent of the Nth religious orders, the cults of mountains called “Nth” or “Siddha” have persisted.

These traditions are particularly strong in western India, as a number of royal chronicles and popular traditions demonstrate. A relatively recent case concerns Mn Singh of Jodhpur, the early nineteenth-century Rathore king of Marwar. Mn Singh’s story begins at Jalore fort, in southwestern Rajasthan, where he and his army were besieged by his evil relation Bhm Singh between the months of July and October 1803. Mn Singh was poised to surrender to Bhm Singh, when the latter suddenly died, opening the way for the young prince to return to Jodhpur and claim the throne, which he did in early November. This story, which has been told and retold by many historians and hagiographers, has also been told by its protagonist, Mn Singh himself. In his own version of the story, recorded in his Mahrja Mn Singh r Khyt, Jalandhar Carit, and Jalandhar Candroday,48 it is a Nth Siddha named yas Dev Nth, the stronghold of Jalore itself (whose ancient names include Jlandhara, Jlandhar, and Jlndhar), and its local deity, named Jlandharnth, that are highlighted.49

Mn Singh had decided on September 16, 1803, that he would surrender ten days later, on Dpval, if there was no change in his situation. It is here that the supernatural intervenes in his accounts. Writing in his Jalandhar Carit, Mn Singh states that he placed all his faith in the venerable Jlandharnth,50 whom he also calls Siddhanth, Siddhevara, Jogendra, Jogrj, and Nth at other points in the text. So it was that on the eve of Dpval itself a miracle occurred:

The Nth produced a miracle in that difficult time,

giving his proof one day at morningtide—

On the tenth of the bright fortnight of Avin,

at an auspicious hour and moment on that holy day,

His two beautiful footprints shone,

on the pure and fine-grained yellow stone . . .

The king touched his forehead to those feet:

rnth has come to meet the king!51

Jlandharnth left the yellow mark of his footprints on the living rock of the mountain stronghold in which Mn Singh and his army were besieged. The name of this mountain, upon which the fort was built, is Kalashacal (“Water-Pot Mountain”), a peak already identified with Jlandharnth prior to this epiphany: in fact, Mn Singh had passed much of his youth at Jalore and was steeped in its traditions concerning the god.52 Below that summit there existed a cave that is still identified with Jlandharnth, known as Bhanvar Gupha, “Black Bee Cave,” whose name is a clear reference to the uppermost cakra of the yogic body.53 It would likely have been at this site that the epiphany of Jlandharnth’s footprints would have taken place.

Mn Singh took the mark of Jlandharnth’s feet to be visible proof that the god had come there, and that the siege would soon be lifted. The Mahrja Mn Singh r Khyt further relates that on the following night, yas Dev Nth—the custodian of the site, who had himself gone to worship the god—received the order from Jlandharnth that if Mn Singh would hold the fort until October 21 (the bright sixth of the lunar month of Karrtik), he would not have to surrender, and that the kingdom of Jodhpur would be his.54 When he related this to Mn Singh, the prince replied that if such should come to pass, yas Dev Nth would share his kingdom with him.55 With one day remaining, Mn Singh received the news of Bhm Singh’s death. He then praised yas Dev Nth and acknowledged that the Nth Siddha was truly Jlandharnth incarnate: “Your body too is that of a Nth, in matter and form; you are yourself the world-protector Jlandharnth!”56

It is important to note here that, apart from the mention of the yellow mark of his footprints left on the floor of his shrine, Mn Singh himself never states that Jlandharnth intervened in his miraculous deliverance from the siege of Jalore. Rather it is his relationship to the undeniably human figure yas Dev Nth, whom the young king rewards following his enthronement in Jodhpur in November 1803, that is emphasized in his writing. Mn Singh’s poetic treatment of Jlandharnth squares with the nature of the latter’s cult in Jalore, and in Marwar in general: Jlandharnth, although he once lived as a yogin on the tapobhmi of Water-Pot Mountain and the Black Bee Cave, is in fact a god who chose to incarnate himself as a yogin at that time.57 The Nth Caritr, a work commissioned by Mn Singh, is deliberately ambiguous on the subject: “I know not whether it was a muni, a Siddha, or a man who made his seat at that place. His ancient supreme form has dwelt there for many eons.”58

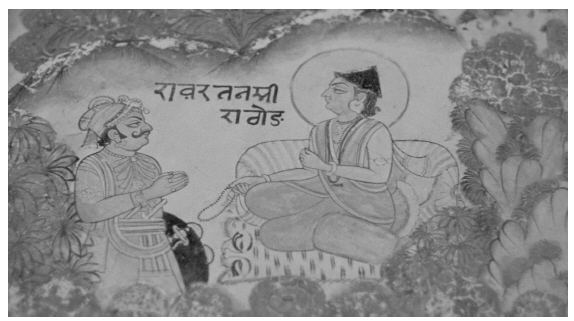

Figure 6.a. Rajput prince kneeling before Nth Siddha in a mountain setting. Freize from Mahmandir, Jodhpur, built by Mahrja Mn Singh in 1804 C.E. to honor yas Dev Nth. Photograph by David Gordon White.

Jlandarnth’s role as a local mountain god intersects that of a number of other regional deities from western India. Mallinth, another figure in the history of the Rathore Rajputs, is another Rajasthani case in point. This historical figure, who was a fourteenth-century military champion of the Rathores, has a name that may be construed as “lord of the mountain” (male in Kannada; mallai in Tamil).59 Tradition maintains that he was, in addition to being a warrior, a perfected man (siddh puru) and a yogin. When he died, in 1399, a tumulus (samdhi) and temple were erected at his place in Tilwada village in Barmer District, where a cattle fair is held annually in the month of Caitra. The entire mountainous region of western Marwar, called Malani, is named after him.60 Near the town of Alwar in eastern Rajasthan, there is a hill named Booti Siddh (“Perfected One of Healing Herbs”), to which Ayurvedic physicians come to collect those herbs (ja-b), and which is said to be named after a hermit who lived there.61 Here, I would argue, it was originally the hill itself that was called “Siddha,” and that its identification with a human who dwelt there was made at a later date. Simon Digby reports a similar denomination of a hill, near Monghyr in Bihar. In this case, the holy man identified with the hill, whose site is marked by a shady margosa tree,62 is a Muslim saint. The hill is therefore called Pr Pah, the “Hill of the Saint”; in India the Islamic “Pr” is the cognate of the Hindu “Nth Siddha,” as witnessed in the Islamicized name of Matsyendranth, which is “Morcha Pr.”63

A similar situation obtains at Jodhpur, where the imposing royal fort standing atop the towering promontory that dominates the modern city of Jodhpur was built, according to legend, at the site of a hermit’s lair. That site, called Ciynth k Dhn, the “Fireplace of the Lord of the Birds,” is located at the base of a cliff that rises up to form the western face of the fort’s promontory. Atop the cliff, perhaps fifty meters above Ciynth k Dhn, is the great royal temple of the goddess Cmu; and constantly rising and falling on the winds that blow constantly at that place are dozens of kites, the same dark, massive birds that are emblazoned on the coat of arms of the house of Marwar. Here again, it was most probably the mountain itself that was called “Lord of the Birds,” before the site became identified with a solitary human inhabitant. And if the Lord of the Birds was in fact a “Siddha mountain” itself, its Yogin consorts were already there as well, in the form of the birds that made it their home: we have demonstrated the avian origins of the Yogins in chapter 2.

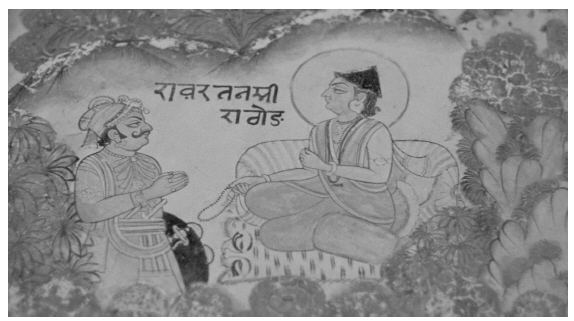

In the light of these data, we may see that the “birthplaces” of the Siddhas and Yogins outlined in chapter 8 of the KJñN, as well as the prescribed sites at which human Siddhas and Yogins are to gather together for the Kaula rites—that is, on clan mountains (kula-parvatas), mounds (phas) generally identified with mountaintops, and fields (ketras)—correspond precisely to the early mythology and lore of the semidivine Siddhas, who were themselves mountains, and their Yogin consorts, who were the wild creatures inhabiting those mountains (fig. 6.b).

Apart from the great Himalayan peaks, the prototypical mountain god of India is Srisailam, the “Venerable Peak” located in the heart of the Deccan, in the Kurnool District of Andhra Pradesh.64 The Maharashtran legend of Siddharmayya—closely connected, according to Günther Sontheimer, with the story of Siddhevara (also a name of Jlandharnth in Mn Singh’s writings) of Sholapur—relates man and mountain in ways that we have already seen. Here, a mute Ligyat herder child named Siddharmayya is taking care of his father’s cattle when Mahdeva (iva) appears to him in the form of a wandering Jagama (Ligyat) ascetic and asks him for some hur (immature kernels of millet or barley). Siddharmayya gives him these, at which point the ascetic, whose name is Mallayya, asks the child for some rice mixed with yogurt. Siddharmayya runs to his mother and asks for food for the Jagama. His mother is astonished that he can speak. He runs back to the spot, but the ascetic has disappeared.65

Here, the ascetic Mallayya is a human incarnation of the Srisailam mountain itself, which was worshiped as a deity in its own right, under the name of Mallana or Mallayya (“Mountain”) before becoming identified in later centuries with the aiva jyotirligam named Mallikrjuna.66 Among the Ligyats, whose historical base has always been the western Deccan plateau, the Vra-Baañjas, the master merchants of this western region, had a mountain (gua-dhvaja) as the coat of arms on its banner. Khaob, a widely worshiped deity in this region—himself said to be the “apotheosis” of a Ligyat merchant—is also known by the name of Mallayya in Karnataka. The most common names for Ligyat and Kuruba men are Mallayya, Mallpp, Malle, and Mallinth. As an incarnation of iva, the divine Khaob-Mallayya has a close connection with mountains: this points to the likelihood that the name Mallayya is derived from the Kannada male (“mountain”) and ayya (“father,” “lord”).67

Figure 6.b. Th Yogin, Bheraghat Yogin temple, Jabalpur District, Madhya Pradesh, ca. 1000 C.E. The swirling motifs in the foreground represent either mountain peaks or clouds. Courtesy of the American Institute of Indian Studies.

The same Siddhevara of Sholapur is the subject of a rich body of mythic tradition in other parts of the interior of Maharashtra, where he is variously named Siddhevara, id, idob, Mhasva-id, Siddhanth, or simply Nth.68 This figure is identified with the deity of the Siddhevara temple of Mhasvad (Satara District), whose cult was established there, according to an 1138 C.E. inscription, through a land grant made by an ancestor of the Kalacuri king Bijjala of Kaly, a Cukyan vassal.69 In one of these local myths, Siddhanth is a “sannys” sent to the underworld by akara (iva) to confront Jogevar, one of the “Seven Sisters” of Dhangar tradition, whom he wins and makes his wife.70

The same Siddhevara is identified as a human figure who in 1136 C.E. constructed a great water reservoir in Sholapur (Sholapur District), and who, through the performance of religious austerities, attained many siddhis. Curiously, or not so curiously, Siddharja, a Cukya king of Anahilva between the years of 1094 and 1143 C.E., is said to have carried out an identical construction project, of the Sahasraliga tank, in his capital city, in modern-day Gujarat, hundreds of miles to the northwest.71 Yet Siddhevara has also been a title applied to powerful holy men in western India. So, for example, Revaa, a founder of the Ligyat order, “killed the goddess My [in Kolhapur], who held captive by her valor nine hundred thousand Siddhas or Ligyat saints.”72 Ritual specialists at temples of the deified Revaa and others are themselves called “ids” (Siddhas): these are possessed by the god when they beat their own bodies with swords or sticks. Jostling with these local id traditions are those of Vrs (Vras). In this context, a Vr is someone who knows how to gain special yogic abilities. He has the power to subject the fifty-two spirits or deities (also called Vrs!) to himself, or to master the siddhis, by virtue of which he himself becomes a Siddha.73

4. Locations of the Siddhas in Indian Cosmologies and Soteriologies

Already in the Agni Pura, Srisailam was known as a siddhaketra, a term that may be read in two ways, on the one hand, as field (ketra) of the demigod Siddha identified with the mountain itself, and as the field upon which human Siddhas lived and practiced.74 The KSS calls the Mountain of Sunrise the “field of the Siddhas” (siddhaketra),75 and in a battle scene describes thirteen Vidydhara warrior kings, each in terms of the mountain of which he is the master.76

Jain cosmological sources dating as far back as the second century B.C.E. are particularly rich in detail on the mountain haunts of the demigod Siddhas.77 According to Jain cosmology, the easternmost peak of each of the six parallel east-to-west mountain ranges that divide the central continent of Jambudvpa into seven unequal parts is crowned by a Siddha sanctuary, and therefore named either Siddhyatana (“Abode of the Siddhas”) or Siddhaka (“Peak of the Siddhas”).78 Also according to Jain cosmology, four elephant-tusk-shaped mountain ranges radiate outward from Meru, the central pillar of the entire world system. The first peak of each of these ranges is named “Siddha.”79 Located closer to the periphery of the terrestrial disk is Nandvaradvpa, the eighth continent of the Jain cosmos, at which this configuration is repeated, with the important difference that this mountain system features a Siddha temple sanctuary on every one of its peaks.80 As such, Nandvaradvpa is a veritable Siddha preserve, a continent reserved for the festive gatherings of these demigods.81 Here, it is most particularly four Mountains of Black Antimony (Añjanagiris), located at the four cardinal points of this continent, that are crowned by Siddha shrines. The earliest extant graphic representation of this continent is a bas-relief in stone, dated to A.D. 1199–1200, and housed in a temple on Girnar, itself a Siddha mountain.82

Hindu religious literature locates the Siddha demigods in a number of venues. According to certain recensions of the MBh—which adhered to the early “four-continent system” of Hindu cosmography—the paradise “Land of the Northern Kurus” (Uttarakuru), located to the north of Mount Meru, lies on the far shore of the ailoda (“Rock Water”) River, whose touch turns humans to stone. On either shore of this river grow reeds that carry Siddhas to the opposite bank and back. This is a country where the Siddhas live together with divine nymphs in forests whose trees and flowers, composed of precious stones, exude a miraculous resin that is nothing other than the nectar of immortality itself.83 This Uttarakuru location is found again in the circa fourth-century Vyu Pura, which names the site Candradvpa, “Moon Island.” This appears to be the earliest reference to this important mythic toponym, which I have discussed at length elsewhere, and which has already been evoked in chapter 4:

To the south of Uttarakuru, there is a moon-shaped island known as Candradvpa, which is the residence of the Devas. It is one thousand yojanas in area and is full of various kinds of fruits and flowers. . . . In its center there is a mountain, in shape and lustre like the moon . . . frequented by the Siddhas and Craas. . . . Therefore, that mountain and land are named as Moon Island and Moon Mountain after the name of the moon. . . .84

The Varha Pura locates Siddhas in mountain valleys immediately to the west of Mount Meru. According to this source, there lies between the Kumuda and Añjana mountains a wide plain called Mtuluga. No living creature walks there, save the Siddhas, who come to visit a holy pool. This association of Siddhas with a mountain called Añjana (“Black Antimony”) reminds us of the Jain toponym mentioned above;85 while the “moon-shaped” mountains of Candradvpa appear to replicate the “elephant-tusk-shaped” mountain ranges of Jain cosmology simply by another name.

The sixth-century C.E. Bhat Sahit of Varhamihira and a number of Hindu astronomical works locate Siddhapura, the City of Siddhas, at the outermost edge of the central island-continent of Jambudvpa, on the northern point of the compass on the terrestrial equator.86 Several other Hindu sources locate the semidivine Siddhas at an atmospheric, if not heavenly level. The Bhgavata Pura (BhP) situates the Siddhas and Vidydharas at the highest atmospheric level, immediately below the spheres of the sun and Rhu, the descending node of the moon; immediately below them are the other devayoni beings listed in the Amarakoa, the “demonic” Yakas, Rkasas, Picas, and so on.87 This last detail may appear strange, since the Puranic literature generally locates such beings beneath the terrestrial disk, in the netherworlds. We will return to this apparent anomaly later in this chapter. A number of Indian sources situate the Siddhas at the very summit of the cosmic egg. This uppermost level is termed either Satyaloka (“Real World”) or Brahmaloka (“World of Brahm/Brahman”) in the Hindu literature. In Buddhist literature as well, the term Brahmaloka (or Brahmakyika) is employed.88 In Jain sources, in which the term Brahmaloka is employed to designate the entire world system, the name for this highest level of the universe is Siddhaloka, the “World of the Perfected Beings.”

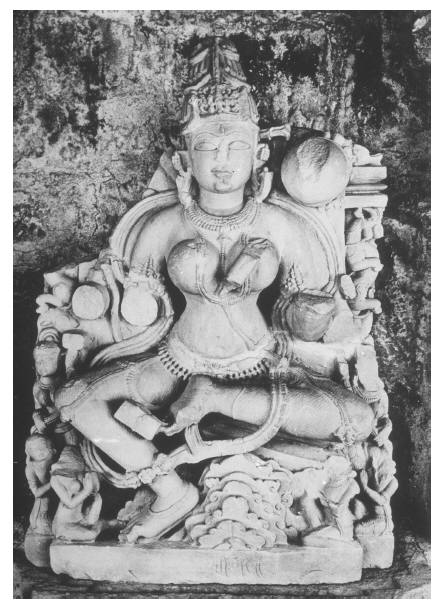

The Jains, who have historically been far more attentive to cosmology than both the Hindus and the Buddhists—by far the greatest number of extant cosmographies are Jain, and cosmography continues to form an important part of Jain religious education—have produced a significant number of descriptions and graphic images of this realm. The Jain Siddhaloka is located at the summit of the “middle world,” on the border between the world (loka) and the nonworld (a-loka). This abode is represented graphically by a crescent moon often described as having the shape of an open umbrella, shown in profile on the forehead of the Loka Purua, the Universal Man (fig. 6.c).89 According to Jain soteriology, the soul, having regained its purity at the end of its ordeals, will leave its mortal remains behind and leap upward, in a single bound, to the summit of the universe, where it will alight beneath the umbrella-shaped canopy that shelters the assembly of the Siddhas.90 Here as well, we may perhaps see in the crescent moon–shaped world of the Jain Siddhas the homologue of the Moon Island of the KJñN.

Figure 6.c. Siddhaloka, portrayed as crescent moon in the forehead of Jain Loka Purua (“Universal Man”), ca. 1700 C.E. Photograph by Rusty Smith. Courtesy of the University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, Virginia.

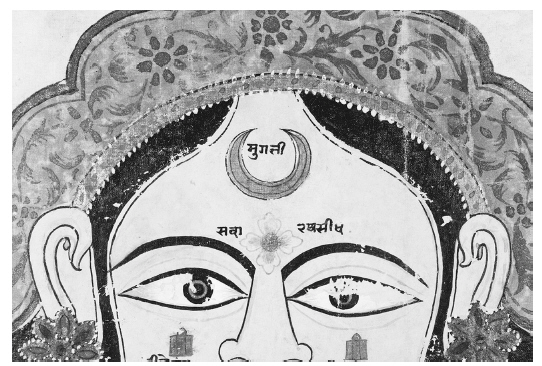

Now, a number of Jain representations of the world system in its anthropomorphized form of the Universal Man, or of Siddhaloka, the World of Perfected Beings, inscribe a man seated in yogic posture at the summit of that world. In these representations, we see, as it were, a yogic homunculus seated in or superimposed upon the cranial vault or forehead of a great man. When we turn to Hindu sources, we find a number of parallel data. An early source is the Bhagavad Gt (8.16), in which Ka evokes the worlds up to the level of brahman (brahmabhuvana) from which creatures return (i.e., are reborn) eternally; “but having reached me, their rebirth does not occur.” Later (15.16–18) he also speaks of three Puruas, which he calls the perishable, the imperishable, and the supreme. The first of these is the stuff of all living creatures; the third, which Ka identifies as himself, is transcendent; and the second, the imperishable, is kastha, “seated on the peak.” Now, when Ka says “seated on the peak,” is he referring to the magnificent isolation of the yogin who practices his austerities on an isolated mountaintop? Or might he not be referring to the subtle peak located within the cranial vault of a meditating yogin (the term triki, “triple-peaked,” is used for a region of the cranial vault in a number of sources), since Ka also refers to the human yogin as being “seated on the peak” at another point in the Gt (6.8)? Artistic depictions of the yogic body often represent either the god iva or a yogin seated in lotus posture in the cranial region (fig. 6.d).91

In many Puras, yogins figure prominently in the highest world, the World of Brahman. The Viu, Vyu, and Skanda Puras place the ascetic sons of Brahm, together with yogins, renouncers, and others who have completed a course of religious austerities, in Satyaloka or Brahmaloka.92 The Brahma Pura locates “Siddha practitioners of yoga who have achieved immortality” in Brahmaloka; and places Goraka—in a likely reference to the historical founder of the Nth Siddhas and haha yoga—there: “There dwell the Siddhas, divine sages, others who practice breath control, and other Yogins the chief of whom is Goraka. They have gaseous bodies. . . . They are eagerly devoted to the practice of yoga.”93 Another Puranic source says of the world of Brahman: “Here, Brahman, the Universal Soul, drinks the nectar of yoga (yogmta) together with the yogins.”94 Here, we must pose the same question as we did regarding the term kastha in the Bhagavad Gt: Is this lofty station where the nectar of yoga is drunk located at the summit of the cosmic egg, or rather that of the cranial vault, where the yogin drinks the nectar of immortality that he has produced through his practice?

5. Exiting the Subtle Body

While most Western scholars tend to view the Puras as repositories of a particularly baroque genre of Hindu mythology, Hindus themselves are more inclined to see them as encyclopedias of early scientific knowledge. When one looks at the mythology of the Siddhas in these works, one finds very little: they are a generally nameless, faceless aggregate whose mythological role is limited to cheering on more individualized gods or heroes. When, however, one turns to religious and scientific inquiry on the nature and location of the Siddhas, the situation changes dramatically: they are the subject of a sustained and highly sophisticated body of speculation that may have had its origins in Greek astronomy, and that “scientifically” described the process by means of which the practitioner truly realized the transcendence of his human condition. In a provocative article on the cosmology of the fourth-century C.E. Viu Pura, W. Randolph Kloetzli demonstrates that, according to the Puranic “logic of projection”—based, as he argues, on an image of the heavens as seen through the stereoscopic projection of the “northern” astrolabe, whose theoretical principles would have been introduced to India from the Hellenistic world in this period—it is through the eye of the supreme god Viu, located at the southern celestial pole (his toe is at the northern celestial pole), that Puranic cosmology is both viewed and projected.95

Figure 6.d. Seated yogin, circumscribed in cranial vault of seated yogin, from a drawing by an Indian artist commissioned by a British officer, 1930 C.E. British Library ADD 24099, f118 (detail). By permission of the British Library.

The most sophisticated and fully developed early discussion of yogic body cosmology, or microcosmology, and its underlying soteriology is found in a slightly later Vaiava work, the circa eighth-century C.E. Bhgavata Purna (BhP). As I will discuss in chapter 8, it is here that the earliest allusion to the location of the six cakras of the subtle body is found: “the sage should, having pressed his heel into the anus, indefatigably raise the breath into the six sites (asu . . . sthneu),”96 culminating in the forehead or fontanel (mrdhan), from which he “will then surge upward into the beyond (param).” I will return to this final element of the yogin exiting his own body momentarily. However, it will first be necessary to give an account of the rvaiava theology and cosmology that undergirds the BhP’s microcosmology.97 According to the rvaiava doctrine of the four vyhas (“bodily arrays”), it is the supreme deity Vsudeva who impregnates his own central womb and gestates the fetus that will develop into the cosmic egg (brahma) within which we exist.98 The Vsudeva vyha is thus at once “the body at whose center we exist, [and] the body at the center of our own consciousness. . . .”99 As Dennis Hudson explains:

In the case of humans, the mapping places the gross body on the outside with the subtle body and soul enclosed by it and the vyha Vsudeva controlling from the center as the Self of all selves. . . . In the case of God, however, the organization of the three bodies is reversed. . . . A difference between God and humans, then, is this: As a microcosm, the human is a conscious soul looking outward through its encompassing subtle body and, by means of that subtle body, through its encompassing gross human body. The Bhagavn, by contrast as the macrocosm, is pure being and consciousness looking “inward” to the subtle body that he encloses and by means of that subtle body, “into” the gross body enclosed within his subtle body. God, one might say, gazes inward at his own center. . . . The ordinary person is not aware that he or she is being watched continuously, literally being seen through at all times by the Pervading Actor (Viu) within space-time who never winks. . . .100

A significant number of medieval works on both cosmology and microcosmology afford just such a “god’s-eye view” of the inner cosmos. So, for example, the KJñN, in a very early description of yogic ascent, states that “he [the yogin] sees the threefold universe, with its mobile and immobile beings, inside of his body.”101 Indeed, this is the view ultimately attained by the Nth Siddhas and other “self-made gods” of the medieval period, who incorporated haha yoga into their practice. The means by which the Siddha is able to gain a god’s-eye view is central to Siddha soteriology, to the bodily apotheosis that is the point of intersection between theology, cosmology, and “microcosmology.”

This notion of apotheosis appears to be addressed in the BhP account of the “six sites”—which portrays the practitioner as exiting his own body to surge upward into “the beyond.” Before we go into the details of this process, let us pause for a moment to consider its context. The second chapter of the second book of the BhP is entitled “Description of the Great Man” (mahpurua), by which, of course, the god Viu is intended, as is made clear by an extended description of the “four-armed Purua” who is to be visualized, “by Lords Among Yogins (yogvaras), within their hearts.”102 The departure of the yogin from his own body into the beyond is presented in this passage as the first of two alternatives. The second alternative is introduced in the verse that follows: “If [however], the wise one wishes to accede to the realm of the highest [Brahm], which is none other than the abode of the Sky-Dwellers . . . he may go there with his mind and senses [intact].”103 While the first alternative may be read as a sort of “out-of-body experience,” this second appears to approximate most closely the notion of bodily apotheosis. The ambiguity of this state is addressed directly in the following verse: “It is said that the realm (gati) of the Masters of Yoga, whose souls are [contained] within their [yogic] breaths, is [both] inside and outside of the triple-world. They do not reach this realm through acts. They partake [of it] through vidy (occult knowledge, the magical arts), tapas (heat-producing austerities), yoga, and samdhi.”104 This idea is not original to the BhP: the Epic Valakhilyas constituted a class of Siddhas, that “include[d] saints of both worlds,” who “ha[d] attained the Siddha realm (siddhagati) through asceticism.”105

The BhP continues, in a passage likely inspired by the fourth- to second-century B.C.E. Maitri Upaniad,106 by describing the practitioner as rising, via “the resplendent medial channel that is the path of brahman,” to a series of higher and higher worlds, identified with the high Hindu gods. Then,

wheeling over the top of the navel of the universe [which is] venerated by knowers of brahman, he ascends alone, with a soul that has been purified and reduced to the size of an atom, [to that world] of Viu at which the wise enjoy a lifespan of one kalpa. Here, beholding the universe [as it is] being consumed by the fire [spat] from the mouth of Ananta, he proceeds to that [world] of the highest [Brahm], where the Lords of the Siddhas are wont to dwell, [which endures] for a period of a life of Brahm (dvaiparrdhyam).107

Four of the verses that follow are of signal interest, because they indicate a simultaneity, if not an identity, between transformations occurring on both microcosmic and macrocosmic levels. Here, the practitioner rises to ever-subtler levels of being, piercing or merging with the seven sheaths of the cosmic egg as he simultaneously implodes their corresponding elements into their higher evolutes within his bodily microcosm. Having now transcended the hierarchy of subtle and gross elements, he effects the dissolution or implosion of these into the ego (here termed vikrya), and so on until the final dissolution of the tattvas into pure consciousness (here termed vijñna-tattva). It concludes: “In the end, [the yogin who is] composed of bliss . . . attains the [state of the] universal self, peace, and beatitude. He who has reached that divine station is never drawn back here again. These . . . are the two eternal paths whose praises are sung in the Vedas.”108 The Vira Pura makes a similar statement: “Having risen above the highest void, the yogin neither dies nor is [re]born, neither goes nor comes. The yogin who has entered into the luminous [firmament] remains [there] from age unto age.” So, too, the Svacchanda Tantra enjoins the practitioner to travel through his own body simultaneous to his peregrenations through the cosmic egg: when he reaches the top, he will find Daapi (the “Staff-Bearer”), who with his staff cracks open the egg/his skull for him to ascend beyond it.109

A remarkably similar ascent, with a strong Kaula coloring, is found in the KM. This same work also provides a glimpse into an intermediary stage in subtle body mapping, inasmuch as it identifies its set of five cakras with the five elements, which it portrays both as encompassing one another like the sheaths of the cosmic egg and aligned vertically above one another along the axis of the spinal column.110 Other Kubjik traditions locate the Siddhas inside the yoni of the goddess, which is itself located above the cranial vault at a site knows as “Beyond the Twelve” (dvdanta) that is both “inside” the yogic body and “outside” the physical body. As the source of mantras, the triangle of the yoni is subdivided into fifty smaller triangles, nested inside of it, each of which contains a Sanskrit phoneme, worshiped as a Bhairava or a Siddha.111

Yet another type of yogic apotheosis is described in the eleventh-century C.E. Rasrava, an alchemical work that offers a great wealth of data on becoming a Siddha, a self-made god. In its discussion of “revivifying water” (sajvanjalam), this source relates that the alchemist who has drunk three measures of this elixir swoons, and then awakens to find himself transformed and possessed of supernatural powers. After further treatment, “he suddenly disappears from human sight and becomes the lord of the Wizards (Vidydharas), surrounded by a circle of Siddha-maidens for a period of fourteen kalpas.”112 Later it concludes a description of khecar jraa (“calcination of mercury that is possessed of the power of flight”) by stating that the alchemist who ingests said mercury is uplifted immediately into the presence of the gods, Siddhas, and Vidydharas, with whom he flies through the air at will.113 The entire work concludes on a similar note: “When all the fixed and moving beings in the universe have been annihilated in that terrible flood of universal dissolution, the Siddha is absorbed into the same place as are the gods.”114

The place in question is, once again, Brahmaloka or Siddhaloka, which Puranic soteriology describes as a holding tank of sorts for gods, demigods, and liberated souls. This soteriology centers on the fate of creatures located in the three uppermost levels of the cosmic egg at the end of a cosmic age (mahyuga). The lowest of these, the fifth of the seven worlds (lokas), is called the World of Regeneration (janarloka), for it is here that those souls whose karma has condemned them to rebirth are held in suspension while all that lies below within the cosmic egg—bodies and mountains, the entire earth and the subterranean worlds—has been burned up and flooded out in the universal dissolution (pralaya). The two worlds above the world of regeneration, the highest worlds within the cosmic egg, are called the World of Ascetic Ardor (tapoloka) and the World of Brahman (brahmaloka), respectively. Their names are descriptive of the nature of their inhabitants, for it is in these that the souls of practitioners who have realized the absolute (brahman) through their heat-producing austerities (tapas) reside during the cosmic night.

The division between these upper levels, that is, between the world of generation and the paired Worlds of Ascetic Ardor and Brahm/Brahman, is brought to the fore in the process of the reordering of the internal contents of the cosmic egg at the beginning of a new cosmic age. After the god Brahm has restored the earth, netherworlds, heavens, landforms, and bodies of creatures to their respective places, then those souls that are bound by their karma to rebirth in the world—souls that have been held in suspension in the World of Regeneration—are reinjected into the bodies befitting their karmic residue. However, those souls that have, through yogic practice, realized liberation, remain ensconced in tapoloka and brahmaloka. Suspended high above the general conflagration, they are saved from universal dissolution and, most importantly, from reincarnation into a transmigrating body. According to the same Puranic traditions, these souls remain in the two uppermost levels until the end of the kalpa, at which point the entire cosmic egg is dissolved. Yet, as we have seen in the Rasrava passage just quoted, the self-made Siddha sports in that lofty world for no less than fourteen kalpas, that is, through fourteen mahpralayas. How is it possible for Siddhas to remain at the summit of the cosmic egg through fourteen mahpralayas in the course of which the entire universe—the “egg” itself—is itself destroyed and reduced to ashes? Where are they when they sport with the Siddha maidens and Wizards for fourteen kalpas?

An indirect response to this question may be found in the Harivaa, the BhP, the T, and the Svacchanda Tantra, all of which ambiguously represent the Siddhas and Vidydharas as inhabitants of both atmospheric and lower regions, as well as mountains. As we have already noted, the BhP (5.24.2–5) situates these perfected beings at the highest atmospheric level, immediately below the spheres of the moon and Rhu, the descending node of the moon. A series of verses from the T, which is in fact a reworking of an earlier Svacchanda Tantra passage,115 offers a somewhat different account. Having described a number of atmospheric levels located above the terrestrial disk, Abhinavagupta states:

Five hundred yojanas higher . . . at the level of the wind called “Lightning-Streak” are stationed . . . the “lowest-level Wizards (Vidydharas).” These are beings who, when in the prior form of human wizards (vidypaurue), carried out cremation-ground-related practices. When they died, that siddhi rendered them Siddhas, stationed in the midst of the “Lightning-Streak” wind.116 . . . Five hundred yojanas higher . . . there at Raivata itself are the primal Siddhas (disiddh) named Yellow Orpiment, Black Antimony, and Mercury-Ash.117

The toponym Raivata, mentioned in the midst of these sources’ descriptions of atmospheric levels located thousands of miles above the earth’s surface, appears to correspond to a terrestrial location. Raivata was in fact a medieval name for the ring of mountains known today as Girnar, in the Junagadh District of Gujarat. Already in the MBh, one finds Subhadr, the sister of Ka, circumambulating and worshiping Raivtaka mountain; and it is during a festival worship of the mountain itself that she is abducted by Arjuna.118 A Jain source entitled the “Raivatcala Mhtmya” calls it the fifth of the twenty-one Jain siddhdris (Siddha mountains) and states that “here sages who have ceased to eat and who pass their days in devotion . . . worship Nemnth [the 22nd trthakara]. Here divine nymphs and numerous heavenly beings—Gandharvas, Siddhas, and Vidydharas, etc.—always worship Nemnth.”119 A number of Puras, beginning with a circa ninth-century C.E.120 passage from the Matsya Pura, also devote long descriptions to the site, which they term Raivtaka. In these sources we clearly appear to be in the presence of a direct identification of Girnar as both a terrestrial site to which humans come to perfect themselves through Siddha techniques and as an atmospheric or celestial site at which they dwell in their definitively transformed state of semidivine Siddhas. A parallel situation is found in the KSS in which Mount abha, described as an abode of Siddhas, is the site to which the Vidydhara Naravhanadatta goes for his consecration (15.2.43–66), and to which he retires to sojourn for an entire cosmic eon, in the concluding verses of that monumental work (18.5.248).

The pedigree of Raivata-Girnar goes back further still, mentioned as it is in the Mahbhrata both by the name of Raivata and that of Gomanta.121 A detailed description of Gomanta is given in the Harivaa.122 This description is important for a detail it gives concerning its formation and its inhabitants:

The mountain called Gomanta, a solitary heavenly peak surrounded by a group of lesser peaks, is difficult to scale, even by the Sky-goers . . . its two highest horns have the form of two shining gods.123 . . . The interior of this mountain is frequented by Siddhas, Craas, and Rkasas, and the surface of the peak is ever thronged with hosts of Vidydharas.124

6. Upside Down, Inside Out

In this passage Siddhas, Craas, and Rkasas are depicted as dwelling inside Gomanta while the Vidydharas are said to dwell on its surface. Here, I will offer an empirical explanation for this description, followed by a more esoteric one. Like many sacred mountains, Girnar is riddled with caves, of which at least two (the caves of Datttreya and Gopcand) are identified with Nth Siddhas, and one could conceive that cave-dwelling Siddhas might be portrayed as living inside this mountain, with other beings, human and semidivine, inhabiting its surface.

But this is not the sole possible explanation. Here, let us recall Ka’s Bhagavad Gt discussion of both the universal Purua and the human yogin as kastha—situated on or in the peak—and the fact that the “triple peak” (triki) is a feature of the yogic body, located within the cranial vault. This corresponds to a feature of iva’s abode of Mount Kailsa, as described in the KSS (15.1.61–75): one may pass through this mountain via a cave called “Triira,” a name that may also be read as “triple peak.” Let us also recall the BhP description of the apotheosis of the yogin, whose ascent to the realms of the Siddhas in Brahmaloka and his implosion of the lower tattvas into their higher essences are shown to be one and the same process.125 Finally, we should also bear in mind the Puranic doctrine concerning the fate of the souls of this universe at the end of a kalpa, with the mahpralaya. Unlike the pralaya that marks the transition between two mahyugas, the mahpralaya entails the calcination of the entire cosmic egg, rather than merely its contents. While the ashes that are the end product of this process come to constitute the body of Ananta, Viu’s serpent couch, it is the fate of souls to be reabsorbed into Viu, the Great Yogin (mahyogin), who holds them in his yogically entranced consciousness. In his state of deep yogic trance, Viu’s consciousness would be concentrated in his cranial vault, and perhaps the subtle triple-peak configuration (triki) located therein.

Might this be an explanation for the Jain imagery of the Siddhaloka, which depicts a yogin seated in the forehead area of the Loka Purua, beneath a crescent moon–shaped umbrella? And might not the locus of the world of the Siddhas—now portrayed as a mountaintop, now as an atmospheric region, and now again as the level located just beneath the inner shell of the top of the cosmic egg—in fact also be a place located just beneath the cranial vault of god, the cosmic yogin? This reading appears to be supported by statements made in Patañjali’s Yoga Stras (YS 3.5) on the attainment of supernatural powers of insight (jñna) through the meditative practice of mental restraint (sayama).126 Whereas Patañjali simply states, in YS 3.26, that “through sayama on the sun, [one gains] insight into the cosmic regions,”127 the bhya to this work, later attributed to Vysa, adds a detailed “Puranic” cosmology of the cosmic egg and its inhabitants, stating in its conclusion that the yogin, by concentrating on the “solar door” of the subtle body, obtains a direct vision of the universe in its entirety. A few verses later (YS 3.32), Patañjali concludes his discussion with “In the light of the fontanel is the vision of the Siddhas,”128 which the bhya glosses by stating: “There is an opening within the cranial vault through which there emanates effulgent light. By concentrating on that light, one obtains a vision of the Siddhas who move in the space between heaven and earth.”129

Where are these Siddhas that one sees through one’s yogic practice? Are they inside or outside of the body? And if the latter, are they to be situated inside mountains or on their surface, or indeed under the cope of heaven; that is, are they inside or outside of the structure of the universal macrocosm or of some intermediate space-time? Perhaps it is not a matter of either/or here. As we have seen, the BhP portrays the practitioner’s apotheosis as his simultaneous piercing of the seven sheaths surrounding the cosmic egg and his internal implosion of their corresponding elements into their higher evolutes within his bodily microcosm. In the medieval Siddha traditions, a mountain cave was the macrocosmic replica of the cranial vault of the meditating yogin as well as of the upper chamber of a meso-cosmic alchemical apparatus within which the alchemist transformed himself into the opus alchymicum. The Möbius universe of the Siddhas was so constructed as to permit its practitioners to at once identify cosmic mountains with their own subtle bodies, and to enter into those mountains to realize the final end of their practice, the transformation of themselves into the semidivine denizens of those peaks. In other words, the Siddha universe was so constructed as to enable the practitioner to simultaneously experience it as a world in which he lived, and a world that lived within himself. The realized Siddha’s experience of the world was identical to that of the supreme godhead.

Let us return here to Kloetzli’s discussion of the impact of the “logic of projection” that undergirded the Puranic cosmographies, and that led to the development of the astrolabe in India and the West. Noting that the spatial projections of the Puranic dvpas (concentric island continents) present us with mathematical divisions reminiscent of the divisions of time known as the yugas (cosmic ages),130 Kloetzli demonstrates that Mount Meru, the prototypical sacred mountain, is the key to the entire projection of the Puranic cosmograph.131 According to the Puranic cosmology, Meru is an “upside-down” mountain, having the form of an inverted cone, whose flat summit and angled sides, Kloetzli argues, are projections of the celestial Tropic of Cancer and the lines of extension from the southern celestial pole, respectively.132 It is at this pole that the eye of Viu is located, the toe of whose upraised foot (uttna-padam, paramam-padam) is located at the north celestial pole.133 Kloetzli concludes:

If the Hindu cosmograph is not an astrolabe in every detail, it is nevertheless certain that it is a scientific instrument whose design is intended for the measure of time—time considered as the body of the deity for theological purposes by the Viu Pura—and involving a projection of the heavens and their motions onto a planar surface. Mount Meru—represented as an inverted cone—is the definition of that projection as it connects the celestial Tropic of Cancer with the south celestial pole, which is the viewing point from which the projection is made. . . . The fact that 16,000 yojanas of the mountain are said to be “underground” may be understood as a statement that this portion of Mount Meru is below the equatorial plane. . . . Since the shape of Mount Meru confronts us again with a logic of projection . . . it means that what is “above” is also here “below.” . . . The gods (devas) and demons (asuras) who reside in the heavens and hells above and below the earth also reside in the mountains of the earth.134

From the perspective of the divine Viu or of the perfected Siddha, above and below, inside and outside, even time and space converge. It is this that allowed the Siddhas to locate themselves in the world, and the world in themselves—viewed as if through a camera obscura—and armed with this knowledge, to transcend this world and look “down” on it from “below,” to situate themselves atop and inside sacred mountains, or within and without the shell of the cosmic egg and their own cranial vaults, at the endpoint of a space and time they now controlled. Additionally, it was in this way that human Siddha practitioners were enabled to view the divine Siddhas located beneath the vault of heaven within their own cranial vaults—in a word, to internalize them—in their own efforts to join their heavenly ranks. It is at this intersection of cutting-edge medieval cosmology and soteriology that the Tantric internalization—of the entire cosmic egg into the subtle body microcosm—was first theorized.

It is tantalizing to note that the prototype for this Hindu body of theory and practice—of both the “logic of projection” and “inner” travel to “higher” worlds—may have been Greek. The notion of the spinal column as a channel for semen and seminal thoughts (logoi spermatikoi) was both a medical and a mystical notion dear to the Stoics. Here, however, I wish to concentrate momentarily on a pre-Pythagorean doctrine that was formative to Plato’s theory, found in the Phaedo, of cyclic rebirth and the recovery of lost knowledge as “recollection,” anamnesis. This doctrine identified the female soul (psyche) with the breath (pneuma) that was flung upward through the head via the action of the diaphragm (prapides) to travel to higher worlds. The female psyche was a divinity that inhabited the human body and a person’s spiritual double, whose function it was to link individual destinies to the cosmic order. Whereas in most people the female psyche did not leave the body to travel to the higher worlds until their death, the case was a different one for persons initiated into the esoteric practices of the diaphragm and breath. These persons, as part of their “spiritual exercises” of rememoration and purification, would undertake “practice in dying” (melete thanatou), by which they would fling their female psyche into the higher worlds to rememorate all the wisdom they had lost in the process of rebirth. The psyche would be made to rise along the same channel as the seminal thoughts, but would then continue beyond the cranium to the higher worlds where wisdom resided.135