Chapter 8

THE SUBLIMATION OF THE YOGIN:

The Subordination of the Feminine in High Hindu Tantra

In the opening chapter of this book, I suggested that it was sexual practice and in particular the ritualized consumption of sexual fluids that gave medieval South Asian Tantra its specificity—in other words, that differentiated Tantra from all other forms of religious practice of the period. This, the “hard core” of South Asian Tantra, first appeared as a coherent ritual system—the Kaula—in about the eighth century in central India; and there have since been more recent revivals of the original Kaula impetus, in fourteenth- to sixteenth-century Bengal and Nepal in particular. However, throughout most of South Asia, a marginalization of Kaula practice occurred in elite brahmanic circles, from a very early time onward, which sublimated the “hard core” of Kaula practice into a body of ritual and meditative techniques that did not threaten the purity regulations that have always been the basis for high-caste social constructions of the self.

The sublime edifice of what I have been calling “high” Hindu Tantra in these pages has been, in the main, an internalization, an aestheticization, and a semanticization of Kaula practice. It has been the transformation “from a kind of doing to a kind of knowing,” a system of “overcoding” that has permitted householder practitioners to have it both ways and lead conventional lives while experimenting in secret with Tantric identities.1 This transformation, which was effected over a relatively brief period of time, between the tenth and the twelfth centuries, especially involved the subordination of the feminine—of the multiple Yogins, Mothers, and aktis (and their human counterparts) of Kaula traditions—to the person of the male practitioner, the male guru in particular. This subordination occurred on a number of levels that involved: (1) the internalization of the Yogins and their circles into the cakras of hathayogic practice; (2) the semanticization of the Yogins into seed mantras; (3) the masculinization of Tantric initiation; and (4) the introduction of ritual substitutes for the referents of the five M-words, including maithuna.

1. Prehistory of the Cakras

In his masterful book The Kplikas and Klmukhas, David Lorenzen makes the following cogent point concerning the goals of yogic practice:

In spite of abundant textual references to various siddhis [supernatural enjoyments] in classical Yoga texts, many modern Indian scholars, and like-minded western ones as well, have seized on a single stra of Patañjali (3.37) to prove that magical powers were regarded as subsidiary, and even hindrances, to final liberation and consequently not worthy of concentrated pursuits. This attitude may have been operative in Vedntic and Buddhist circles and is now popular among practitioners imbued with the spirit of the Hindu reformist movements, but it was not the view of Patañjali and certainly not the view of mediaeval exponents of Haha Yoga.2

It suffices to cast a glance at the Yoga Stras to see that the acquisition of siddhis was at the forefront of yogic theory and practice in the first centuries of the common era: nearly all of the fifty-five stras of book 3 of this work are devoted to the siddhis, and the “disclaimer” in verse 37 of this book—that “these powers are impediments to samdhi, but are acquisitions in a normal fluctuating state of mind”—seems only to apply, in fact, to the siddhis enumerated in the two preceding verses. This is a view shared by P. V. Kane.3

One finds very little of yogic practice, in the sense of techniques involving fixed postures (sanas) and breath control (pryma), in the Yoga Stras. They are, of course, the third and fourth limbs of Patañjali’s eight-limbed yoga (2.29); however, in the grand total of seven stras (2.46–52) he devotes to them, Patañjali gives absolutely no detail on these matters, save perhaps a veiled reference to diaphragmatic retention, which he terms stambha-vtti (2.50). References to the subtle body, the channels (ns) and energy centers (cakras), are entirely absent from this work (although the bhya does briefly describe a limited number of sanas). It would appear in fact that the circa sixth-century B.C.E. Chndogya Upaniad (8.6.6) had already gone far beyond Patañjali and his commentators when it stated: “There are a hundred and one channels of the heart. One of these passes up to the crown of the head. Going up by it, one goes to immortality. The others are for departing in various directions.”

Moreover, Patañjali’s “classical” definition of “yoga” notwithstanding,4 many if not most pre-twelfth-century accounts of the practice of “yoga,” going back to the MBh,5 describe it not as a form of meditative or physical practice, but rather as a battery of techniques for the attainment of siddhis, including out-of-body experience, entering the bodies of others as a means to escaping death or simply to feed on them, invisibility, the power of flight, transmutation, and so on.6 Similarly, the term “yogin” (or yogevara, “master of yoga”), like its feminine form yogin (or yogevar), most often means “sorcerer” or “magician” in pre-twelfth-century sources: thus, for example, Kntaila, the rogue ascetic of the frame story of the KSS, is called a yogin; and Bha, who makes a meal of King Baka in the Rjataragi, is called a yogevar.7 The “Tantric yoga” that is being marketed in places like Hollywood has elided several centuries from the history of the origins and development of yoga, and altered its content beyond recognition.

In this section I will trace the development of a number of elements specific to haha yoga as such emerged in a variety of Hindu and Buddhist sources between the eighth and twelfth centuries C.E. These sources are the eighth-century Buddhist Hevajra Tantra and the following Hindu sources: the eighth-century Bhgavata Pura (BhP) and Tantrasadbhva Tantra; the ninth- to tenth-century KJñN; the tenth- to eleventh-century KM and Jayadrathaymala; the eleventh-century T; the eleventh- to twelfth-century Rudraymala Tantra; and the twelfth-century rmatottara Tantra. In this historical analysis, I will discuss (1) the emergence of the subtle body system of the cakras; (2) the projection of powerful feminine figures from the external world of Tantric ritual onto the grid of the subtle body; and (3) the role of these now-internalized feminine energies, including that known as the kualin, in the male practitioner’s attainment of siddhis.

One need not go back very far to find the principal source of the seemingly timeless system of the six plus one cakras: this is Arthur Avalon’s edition and translation of a late work, the Sacakranirpaa, as the principal element of his seminal study, The Serpent Power.8 Perhaps due to the power of the illustrations of this configuration in Avalon’s work, many scholars have taken this to be an immutable, eternal system, as old as yoga itself, and grounded, perhaps, in the yogin’s actual experience of the subtle body. A case in point is a recent work by Rahul Peter Das, which, while it offers an encyclopedic account of subtle body systems in Bengal, is constantly plagued by the author’s frustration in the face of the inconsistencies and contradictions between those systems.9 In fact, there is no “standard” system of the cakras. Every school, sometimes every teacher within each school, has had their own cakra system. These have developed over time, and an “archaeology” of the various configurations is in order.

We have already noted that Hindus have been worshiping groups of Mothers (mtcakras) since at least the sixth century.10 These were circular arrays of goddesses “in the world,” that is, outside of the body, circles represented in mandalas of every sort, including the circular, hypaethral Yogin temples. The gradual internalization of these powerful female entities was effected by internalizing their formations into the hierarchized cakras of the yogic body. Two early instances of this process may be found in the KJñN and the KM.

We begin with the presentation in the KJñN of six categories of aktis—the “Field-born,” “Mound-born,” and so on—that were outlined in chapter 6.11 Here, a comparison may be drawn with a slightly later source, Kemarja’s eleventh-century commentary to Netra Tantra 19.71. Citing the Tantrasadbhva, Kemarja names these same six categories of aktis, specifying that unlike the Yogins, who dwell in the worlds of Brahm, Viu, and Indra, these six types of aktis all dwell within the body. He then goes on to identify these with six powerful and terrible classes of female entities: the Yogins, Devats, Rupis, kins, bariks, and ivs. Most of these are described as draining the human body of its “five nectars,” its vital fluids, but the language is ambiguous and seems to imply that they do so from without rather than from within. Following its division of the six aktis into internal and external groups of three, the KJñN continues with a description of a seventh type, called “Lowest-born”—that is, an out-caste woman—and then shifts to a description of the worship of a cakra comprised of the sixty-four Yogins and the fifty-eight Virile Heroes, “duly presided over by the Sons of the Clan.”12 Fifteen verses later, two sets of seed mantras—termed the “Clan Group of Eight” and the “Wisdom Group of Eight,” comprised of vowels and consonants, respectively—are presented. These are to be written out eight times, with Clan and Wisdom graphemes interspersed. This entire sixty-four-part arrangement is termed the “Yogin Sequence.”13

It is at this point that the term cakra first comes to be employed in a systematic way in this chapter. One who is devoted to meditation upon and worship of the first cakra, named “Mingling with the Yogins” (yoginmelakam), obtains the eight supernatural powers (siddhis); with the second cakra, one obtains the power of attraction; and with the third, entering into the body of another person; and so on to the eighth, which confers the power of realizing one’s desires and mastery of the six powers of Tantric sorcery. This Great Cakra (mahcakra), raised at its apex (i.e., conical), is ascended through devotion to the Clan. The chapter concludes with the promise that one who knows the sixty-four arrangements becomes perfected, and that the “Sequence of the Sixty-four Yogins” is the concealed true essence of these arrangements.14 This data is repeated with variations in chapter 10, with the practitioner meditating on eight cakras of eight petals each, with the total of sixty-four corresponding to eight sets of eight seed mantras.15

In these KJñN passages, the term cakra is being used in a nontechnical way, to simply denote a circle or grouping of divinities, identified with arrangements of the Sanskrit graphemes. A similar situation obtains in the KM. This work—whose five-“cakra” system comprises groups of devs, dts, mts, yogins, and khecar deities aligned along the vertical axis of the yogic body—nearly never refers to these groupings as cakras.16 According to Dorothea Heilijger-Seelens, the meaning of the term cakra was, in the period in which this work was compiled, generally restricted to the groups of deities located in a mandala, which served as their base or support. The term did not denote a circular array, and even less so one located within the yogic body. Moreover, in those rare cases in which the KM did present the six energy centers by their “standard” names (this is the earliest source in which these are found), it only once referred to one of these—the anhata—as a cakra.17 These conceptual connections would be made later.

While the KM nonetheless insists that these are internal centers or groupings, it betrays a macrocosmic model when it speaks of their dimensions. The lowest group, the Devcakra, identified with the element earth, is said to be one hundred kois (of yojanas, according to the commentary18) in size, with the other, higher groups a thousand, hundred thousand, 10 million, and 1,000 million kois in diameter, respectively. These are the precise measurements and proportions given in the tenth chapter of the Svacchanda Tantra—a text that predates the KM by at least a century—of the cosmic egg (one hundred kois), and the surrounding spheres of water, fire, air, and ether.19 This understanding is already present in the KJñN, a text coeval with the Svacchanda Tantra, which gives a measure often kois “beyond the visible [world]” for “this Kaula,” that is, this embodied universe. Also according to the KJñN, when the practitioner reaches a certain threshold of practice, “he sees the threefold universe, with its mobile and immobile beings, inside of his body. . . . With [an extension of] one thousand kois, he is iva himself, the maker and destroyer [of the universe].”20 The clear implication here is that the various dimensions of the “outer space” of the universe are being directly projected onto the “inner space” of the human body. In these early references, the circles or spheres of the outer elements, even when they are identified with various groupings of female divinities, are still far removed from the later, “standard” notion of the six cakras of the yogic body.21

2. The Emergence of the Cakras as Components of the Yogic Body

The earliest accounts of the cakras as “circles” or “wheels” of subtle energy located within the yogic body are found in the Carygti and the Hevajra Tantra, two circa eighth-century Buddhist Tantric works that locate four cakras within the human body at the levels of the navel, heart, throat, and head.22 These cakras are identified with four geographical sites (phas), which appear to correspond to points of contact between the Indian subcontinent and inner Asia: these are Kmkhy (Gauhati, Assam), Uiyna (Swat Valley?),23 Pragiri (Punjab?), and Jlandhara (upper Punjab). This tradition is repeated in numerous sources, including those of the Nth Siddhas, whose twelfth-century founder Gorakantha identifies the same set of four phas with sites aligned along the spinal column within the yogic body.24 The T offers a slightly longer list of phas “in the world,” before locating the same within the yogic body, a few verses later.25 The Hevajra Tantra26 also homologizes these four centers with a rich array of scholastic tetradic categories, including Buddha bodies, seed mantras, goddesses, truths, realities, schools, et cetera.27 Their locations in the yogic body appear to correspond as well to the mystic locations of the mind in its four states as described in a number of late Upanishadic traditions, which declare that while one is in a waking state, the mind dwells in the navel; during dreamless sleep, it dwells in the heart; during dream sleep, it resides in the throat; and when in the “fourth state” only attainable by the yogin, it resides in the head.28 Later sources locate ten and, still later, fifty-one phas (identified with the Sanskrit phonemes) within the subtle body.29

The vertical configuration of the six plus one cakras that many identify with Hindu subtle body mapping emerges slowly, in the course of the latter half of the first millennium C.E. Perhaps the earliest Hindu source on this system is the BhP, discussed in previous chapters.30 Here, the “six sites” (asu . . . sthneu) named are the (1) navel (nbh); (2) heart (hd); (3) breast (uras); (4) root of the palate (svatlumlam); (5) place between the eyebrows (bhruvorantaram); and (6) cranial vault (mrdhan), from which he “will then surge upward into the beyond (param).” What is the source of this enumeration in the BhP? A glance at the early medical literature indicates that these sites correspond quite exactly to anatomical notions of the vital points of the body (mah-marmi) or the supports of the vital breaths (pryatana). These are listed in the circa 100 C.E. Caraka Sahit as follows: head (mrdhan), throat (kaha), heart (hdaya), navel (nbh), bladder (basti), and rectum (guda).31 Certain later sources add the frenum,32 the membrane that attaches the tongue to the lower jaw, to this list: this would correspond to the root of the palate listed in the BhP.

aivasiddhnta sources give a slightly different account of the centers. These most commonly list five centers, which they call either sites (sthnas), knots (granthis), supports (dhras), or lotuses—but almost never cakras. These are the heart (ht); throat (kaha); palate (tlu); the place between the eyebrows (bhrmadhya); and the fontanel (brahmarandhra). Quite often, the End of the Twelve (dvdanta)—because it is located at twelve finger-breadths above the fontanel—will also be mentioned in these sources, but not as a member of this set of five. So, too, aivasiddhnta works will sometimes evoke the root support (mldhra) in its bipolar relationship to the brahmarandhra, but without mention of the intervening centers.33

The first Hindu source to list the locations found in the BhP, and perhaps the first to apply the term cakra to them as well, is the KJñN:

The various spokes [of the wheels] of divine maidens (divyakanyra) are worshiped by the immortal host in (1) the secret place (genitals), (2) navel, (3) heart, (4) throat, (5) mouth, (6) forehead, and (7) crown of the head. [These maidens] are arrayed along the spine (pamadhye) [up] to the trident (tridaakam) [located at the level of] the fontanel (muasandhi). These cakras are of eleven sorts and comprised of thousands [of maidens?], O Goddess! [They are] five-spoked (pañcram) and eight-leaved (aa-pattram), [as well as] ten- and twelve-leaved, sixteen- and one hundred–leaved, as well as one hundred thousand–leaved.34

This passage continues with a discussion of these divine maidens, through whom various siddhis are attained, each of whom is identified by the color of her garb (red, yellow, smoky, white, etc.). So it is that we find in this source a juxtaposition of (1) the locations of the cakras; (2) the use of the term cakra; (3) a description of the cakras as being composed of spokes and leaves (but not petals); and (4) a portrayal of color-coded divine maidens as dwelling in or on the spokes of these cakras. The problematic remark in this passage, that the cakras are in some way elevenfold, or of eleven sorts, appears to be explicated in the seventeenth chapter of the same source, which names eleven sites, of which six correspond to the six sites or cakras:

The (1) rectum, (2) secret place (genitals), along with the (3) navel [and] (4) the downturned lotus (padma) in the heart, (5) the cakra of breath and utterances (samrastobhakam) [i.e., the throat], (6) the cooling knot (granthi) of the uvula, (7) the root (or tip) of the nose, and the (8) End of the Twelve;35 the (9) [site] located between the eyebrows; (10) the forehead; and the brilliant (11) cleft of brahman, located at the crown of the head: it is the stated doctrine that [this] elevenfold [system] is located in the midst of the body.36

In addition to using the term cakra, this passage also refers to the down-turned lotus (and not wheel) in the heart, as well as to a knot (granthi) located at the level of the uvula.37 It would appear that Matsyendra’s yogic body system contributed to the synthesis presented in the writings of Abhinavagupta. In T 29.37 he names the End of the Twelve, the “upward kualin” (rdhvagakualin), the place between the eyebrows (baindava), heart, umbilicus, and the “bulb” (kandam) as the six “secret places” (chommas) through which the kula is transmitted from teacher to disciple.38 Abhinavagupta’s system also features a trident (triula), located at the level of the fontanel, and a thousand-spoked End of the Twelve. However, we must note that whereas the KJñN discusses these centers as wheels possessed of spokes or leaves, or as lotuses, the cakras of the subtle body in Trika Kaulas sources are whirling spoked wheels that, in the body of the nonpractitioner, become inextricable tangles of coils called knots (granthis) because they knot together spirit and matter.39

Another likely source of Abhinavagupta’s synthesis is the Netra Tantra, of which his disciple Kemarja wrote an extensive commentary. The seventh chapter of this work, entitled the “Subtle Meditation on the ‘Death-Conquering’ [Mantra],” comprises a discussion of two subtle body systems, which Kemarja qualifies as belonging to the “Kaula” and “Tantric” liturgies, respectively.40 Taken together, the two systems presented in the text and commentary appear to be more direct forerunners of the later haha yoga system of Gorakantha than do the KJñN and other works attributed to Matsyendrantha, who was Gorakantha’s guru, according to Nth Siddha tradition. The Netra Tantra’s presentation of yogic practice combines breath control, meditation, “the piercing” of knots and the central channel, the raising of the “akti who is filled with one’s semen” the length of that channel,41 and the internal production of the nectar of immortality.42 At the same time, the Netra Tantra agrees with the KJñN on a number of subtle body locations; for example, the “Fire of Time” (klgni), which it locates at the tips of the toes; and “Fish-Belly,” which it locates at the level of the genitals.43 Such is not the case, however, for the Netra Tantra’s presentation of the six cakras, which is idiosyncratic with regard to every other yogic body system: “The ncakra is [located] in the ‘place of generation’; the [cakra] called my is in the navel; the yogicakra is placed in the heart; while the [cakra] known as bhedana is placed in the uvula. The dipticakra is placed in the ‘drop’ (bindu) and the [cakra] called nta is in the ‘reverberation’ (nda).”44 The sole source to mention any one of these cakras is the eighth-century Mlat-Mdhava, in which it is the ncakra that powers Kaplakual’s flight.45 A mention in the Jayadrathaymala of “my [as] the mother of the phonemes . . . the kualin” may be a reference to the second of the Netra Tantra cakras.46

Returning to the KJñN, yet another discussion of subtle body mapping occurs in this source under the heading of sites (sthnas). Here, it describes eleven of these in terms of their spokes, leaves, and petals (dalas): in order, they are the four-leaved, eight-spoked, twelve-spoked, five-spoked, sixteen-spoked, sixty-four-petaled, one hundred–leaved, one thousand–petaled, 10 million–leaved, 5 million–leaved, and 30 million–leaved.47 It then goes on to discuss a number of other subtle sites (vypaka, vypin, unmana, etc.), located in the upper cranial vault, that one finds in other Kaula sources, including the Svacchanda Tantra and Netra Tantra.48

A final KJñN evocation of the workings of the subtle body will serve to orient us, once again, toward the KM.49 This is the work’s fourteenth and longest chapter, much of which comprises a rambling account of supernatural powers realized by “working the mind” through a sequence (krama) of yogic body locations, variously called cakras and “kaulas” (“clans of internal Siddhas”?).50 Toward the end of this meditative ascent, the KJñN (14.92) evokes “this seal, which is called ‘Unnamed’” (anm nama mudreyam), and states that “sealed with the five seals . . . one should pierce that door whose bolts are well-fitted.” One finds similar language in the KM, for which “Unnamed” is one of the names of the goddess Kubjik.51 Here, the statement “applications of the bolts on the openings of the body,”52 occurs at the beginning of this work’s discussion of “upward progress” (utkrnti),53 which appears to be a type of hathayogic practice. The KM passage continues: “The rectum, penis, and navel, mouth, nose, ears and eyes: having fitted bolts in these places (i.e., the nine ‘doors’ or bodily orifices), one should impel the ‘crooked one’ (kuñcik) upward.”54 Then follows a discussion of a number of yogic techniques—including the Cock Posture (kukusana)—which effect the piercing of the knot[s], confer numerous siddhis, and afford firmness of the self.55

Bhairava, the divine revealer of the KM, next states that he will provide a description of what he calls the “bolt-practices” of the knife (kurikdyargalbhysa), and so on, which effect upward progress (utkrnti-kraam) in him who is empowered to use it, and great affliction in the unempowered. Having already discussed this ritual in earlier chapters, I will not go into a description of its details at this point.56 Here, the salient point of this passage concerns the names of the goddesses invoked and the bodily constituents offered to them. In order, their names are Kusumamlin (“She Who Is Garlanded with Flowers”),57 Yaki, akhin, Kkin, Lkin, Rki, and kin. These Yogins are named in nearly identical order in the eighteenth chapter of the rmatottara Tantra, a later text of the same Kubjik tradition. Here, the names listed are kin, Rki, Lkin, Kkin, kin, Hkin, Ykin, and Kusum.58 They are listed in the same order in Agni Pura 144.28b–29a. In this last case, their names are enumerated in instructions for the construction of the six-cornered Kubjik mandala, with the ordering proceeding from the northwest corner.59 This mandala is identical to the Yogincakra, the fourth of the five cakras of the Kubjik system, located at the level of the throat, as described in the fifteenth chapter of the KM itself.60 A shorter, variant list of these Yogins is found in two places in the KJñN, and chapter 4 of the KJñN, which is devoted to Tantric sorcery, appears to be a source for the data found in a number of later Kubjik traditions.61

What the Yogins are offered is of signal interest here: the first of these, Kusumamlin, is urged to take or swallow (gha) the practitioner’s “prime bodily constituent,” that is, semen; the second, Yaki, to crush his bones; the third, akhin, to take his marrow; the fourth, Kkin, to take his fat; the fifth, Lkin, to eat his flesh; the sixth, Rki, to take his blood; and the seventh, kin, to take his skin.62 Clearly, the bodily constituents these goddesses are urged to consume constitute a hierarchy. These are, in fact, the standard series of the seven dhtus, the “bodily constituents” of Hindu medical tradition (with the sole exception being that skin has here replaced chyle [rasa]), which are serially burned in the fires of digestion, until semen, the “prime bodily constituent,” is produced.63 With each goddess invoked in this passage, the practitioner is offering the products of a series of refining processes.

To all appearances, this is a rudimentary form of the hathayogic raising of the kualin. What is missing here is an identification between the goddesses to whom one’s hierarchized bodily constituents are offered and subtle body locations inside the practitioner. This connection is made, however, in another KM passage, which locates six Yogins, called the “regents of the six fortresses,” as follows: mar is located in the dhra, Rma in the svdhihna, Lambakar in the maipura, Kk in the anhata, Skin in the viuddhi, and Yaki in the jñ.64 In another chapter the KM lists two sequences of six goddesses as kulkula and kula, respectively. The first denotes the “northern course” of the six cakras, from the jñ down to the dhra, and the latter the “southern course,” in reverse order. The former group is creative, and the latter—comprised of kin, Rki, Lkin, Kkin, kin, and Hkin—is destructive.65

A number of later sources,66 beginning with the Rudraymala Tantra, identify these goddesses, which they call Yogins, with the cakras as well as with the dhtus, the bodily constituents. The Rudraymala Tantra’s ordering identifies these Yogins with the following subtle body locations: kin is in the mldhra; Rki in the svdhihna; Lkin in the maipura; Kkin in the anhata; kin in the viuddhi; and Hkin in the jñ.67 Kusumaml, who is missing from this listing, is located in the feet in the rmatottara Tantra;68 other works place a figure named Ykin at the level of the sahasrra.69 These Rudraymala Tantra locations correspond, of course, to the “standard” names of the six cakras of later hathayogic tradition. They are, in fact, first called by these names in the KM, which correlates the six standard yogic body locations with its Yogins of the “northern course.”

Mark Dyczkowski has argued that it was within the Kubjik traditions that the six-cakra configuration was first developed into a fixed coherent system.70 The KM, the root Tantra of the Kubjik tradition, locates the cakras and assigns each of them a number of “divisions” (bhedas) or “portions” (kals), which approximates the number of “petals” assigned to each of these “lotuses” in later sources.71 We also encounter in the KM the notion of a process of yogic refinement or extraction of fluid bodily constituents, which is superimposed upon the vertical grid of the subtle body, along the spinal column, leading from the rectum to the cranial vault. Nonetheless, it would be incorrect to state that there is a hathayogic dynamic to the KM’s system of the cakras. What is lacking are the explicit application of the term cakra to these centers, the explicit identification of these centers with the elements,72 and the deification or hypostasization of the principle or dynamic of this refinement process: here I am referring to that commonplace of hathayogic theory, the female kualin or serpent power—who has perhaps been evoked, albeit not by name, in the statement made in this source that one should, through utkrnti, “impel the crooked one upward” (KM 23.114a).

3. The Kualin and the Channeling of Feminine Energies

The KM makes a number of other statements that appear to betray its familiarity with a notion of this serpentine feminine nexus of yogic energy.73 In KM 5.84 we read that “[akti] having the form of a sleeping serpent [is located] at the End of the Twelve. . . . Nevertheless, she is also to be found dwelling in the navel. . . .”74 This serpentine (bhuja[]ga-kr) akti is connected in this passage to mantras and subtle levels of speech, through which she is reunited with iva. A later passage (KM 12.60–67) describes the sexual “churning” (ma[n]thanam) of an inner phallus (ligam) and vulva (yoni) that occurs in the maipura cakra,75 that is, at the level of the navel. Here, however, the language is not phonematic, but rather fluid: this churning of iva and akti produces a flood of nectar.

This is not, however, the earliest mention of this indwelling female serpent to be found in Hindu literature. This distinction likely falls to the circa eighth-century C.E. Tantrasadbhva Tantra,76 which similarly evokes her in a discussion of the phonematic energy that also uses the image of churning:

This energy is called supreme, subtle, transcending all norm or practice. . . . Enclosing within herself the fluid drop (bindu) of the heart, her aspect is that of a snake lying in deep sleep . . . she is awakened by the supreme sound whose nature is knowledge, being churned by the bindu resting in her womb. . . . Awakened by this [luminous throbbing], the subtle force (kal), Kual is aroused. The sovereign bindu [iva], who is in the womb of akti, is possessed of a fourfold force (kal). By the union of the Churner and of She that is Being Churned, this [Kual] becomes straight. This [akti], when she abides between the two bindus, is called Jyeh. . . . In the heart, she is said to be of one atom. In the throat, she is of two atoms. She is known as being of three atoms when permanently abiding on the tip of the tongue. . . .77

In this passage we may be in the presence of the earliest mention of a coiled “serpent energy”; however, the term that is used here is kual, which simply means “she who is ring-shaped.” This is also the term that one encounters in the KJñN, which evokes the following goddesses in succession as the Mothers (mtks) who are identified with the “mass of sound” (abdari) located in “all of the knots” (sarvagrantheu) of the subtle body: Vm, Kual, Jyeh, Manonman, Rudra-akti, and Kmkhy.78 Also mentioned in this passage are the “female” phonemes called the Mtks (“Little Mothers”) and the “male” phonemes called the abdari (“Mass of Sounds”). Here we already detect the process of the semanticization of the Goddess and her energies, a process that becomes predominant in later Tantric traditions.79 In another passage the KJñN describes Vm as having an annular or serpentine form (kualkti) and extending from the feet to the crown of the head: the raising of this goddess from the rectum culminates with her absorption at the End of the Twelve.80 Once again the kualin serpent appears to be present here in everything but precise name.

Let us dwell for a moment on the names of the Mother goddesses evoked in the KJñN. In aivasiddhnta metaphysics, the goddess Jyeh(dev), mentioned in the KJñN and Tantrasadbhva passages, is described as assuming eight forms, by which she represents eight tattvas: these are Vm (earth), Jyeh herself (water), Raudr (fire), Kl (air), Kalavikara (ether), Balavikara (moon), Balapramathin (sun), and Manonman (iva-hood). This group of eight are said to be the aktis of the eight male Vidyevaras of the aivasiddhnta system, the deifications of the eight categories of being that separate the “pure” worlds from the “impure.”81 With this enumeration, we may surmise that Matsyendrantha was drawing on the same source as the Saiddhntika metaphysicians.82 In addition, we once more see a hierarchization of internalized goddesses, identified here with the five elements (and a number of their subtler evolutes), as well as with the ordering of phonemes within the yogic body. That these are projected upon the grid of the yogic body is made clear by the fact that they are said to be located “in all the knots.” Finally, this list of deities from the Saiddhntika system is complemented by the Mother named Kual whom the KJñN locates between Vm (earth) and Jyeh (water).83 It is a commonplace of later subtle body mapping to identify the five lower cakras with the five elements: Kual would thus be located, according to this schema, between the rectal mldhra (earth) and the genital svdhihna (water).

Jyeh (“Eldest”) is a goddess whose cult goes back to the time of the fifth- to second-century B.C.E. Baudhyana Ghya Stra.84 As was indicated in chapter 2, she is a dread goddess who is mentioned together or identified with such terrible Mothers as Hart, Ptan, and Jar,85 and inauspicious (alakm) astrological configurations: in the Indian calendar, the month of Jyaia, falling as it does in the deadly heat of the premonsoon season, is the cruelest month. Jyeh’s names and epithets are all dire—“Ass-Rider,” “Crow-Bannered,” and “Bad Woman” (Alakm)—and she is depicted in her iconography with a sweeping broom, the symbolic homologue of the winnowing fan carried by the smallpox goddess tal.86 Jyeh belongs to an early triad of goddesses—the other two being Vm and Raudr—who would later become identified with the three aktis (Icch-, Jñn- and Kriy-), the three phonemes A, , and , as well as the goddesses Par, Apar, and Parpar of the Trika pantheon. References to Par, Apar, and Parpar in the Mlinvijayottara Tantra (3.30–33) indicate that this triad was an appropriation of an earlier threefold division of classes of Mothers: those that liberate souls (aghor), those that impede souls (ghor), and those that drag souls downward (ghortar).87

Both the KJñN account of the raising of the ring-shaped goddess Vm from the level of the rectum to the End of the Twelve and the statement in KM 5.84 that akti dwells in the form of a sleeping serpent in both the cranial vault and the navel are precursors of the dynamic role of the kualin in later hathayogic sources. In the KJñN passage, the goddess’s ring shape evokes the circles of Yogins that rise into the air at the conclusion of their cremation-ground rites—and it should be recalled here that the cakras themselves are referred to as cremation grounds in the later hathayogic literature.88 In the KM passage, it is the upward motion of feminine energy that is stressed.

Perhaps the earliest occurrence of the term kualin (as opposed to kual) is found in the third hexad (aka) of the tenth- to eleventh-century Jayadrathaymala,89 which, in a discussion of the origin of mantras from the supreme god Bhairava, relates the kualin to phonemes as well as to the kals, to which we will return:

My is the mother of the phonemes and is known as the fire-stick of the mantras. She is the kualin akti, and is to be known as the supreme kal. From that spring forth the mantras as well as the separate clans, and likewise the Tantras. . . .90

Abhinavagupta, who likely took his inspiration from all of the sources we have been reviewing, develops this principle in his discussion of the upper and lower kualins, which are two phases of the same energy, in expansion and contraction, that effects the descent of transcendent consciousness into the human microcosm, and the return of human consciousness toward its transcendent source. Often he portrays these as spoked wheels that, aligned along a central axis or axle, rise and descend to whirl in harmony with one another. In spite of the highly evocative sexual language he employs, Abhinavagupta’s model is nonetheless one of phone-matic, rather than fluid, expansion and contraction.91

It not until the Rudraymala Tantra and the later hathayogic classics attributed to Gorakantha that the kualin becomes the vehicle for fluid, rather than phonematic transactions and transfers. This role of the kualin in the dynamics of yogic body fluid transfer is brought to the fore in a portion of the Tantric practice of the five M-words, which Agehananda Bharati describes:

When the practitioner is poised to drink the liquor, he says “I sacrifice”; and as he does so, he mentally draws the coiled energy of the Clan (kulakualin) from her seat in the base cakra. This time, however, he does not draw her up into the thousand-petaled sahasrra in the cranial vault, but instead he brings her to the tip of his tongue and seats her there. At this moment he drinks the beverage from its bowl, and as he drinks she impresses the thought on his mind that it is not he himself who is drinking, but the kula-kualin now seated on the tip of his tongue, to whom he is offering the liquid as a libation. In the same manner he now empties all the other bowls as he visualizes that he feeds their contents as oblations to the Goddess—for the kula-kualin is the microcosmic aspect of the universal akti.92

Here, the coiled energy at the tip of the practitioner’s tongue is not spitting phonemes, as in the Tantrasadbhva Tantra passage quoted above, but rather drinking ritual fluids, which are so many substitutes for, or actual instantiations of, vital bodily fluids. One may speculate as to why it is that the feminine principle of yogic energy comes to be represented as a serpent, now coiled, and now straightened. Of course, there seems to be some sort of elective affinity between the kualin’s function and form—however, the avian gander (hasa), which doubles for the kualin in a number of sources, appears to fulfill the same function of raising energy from the lower to the upper body.93 The KJñN’s discussion of the “goddess named Vm” is framed, tellingly, by a disquisition on the hasa:

From below to above the gander sports, until it is absorbed at the End of the Twelve. Seated in the heart it remains motionless, like water inside a pot. Having the appearance of a lotus fiber, it partakes neither of being nor of nonbeing. Neither supporting nor supported, it is omniscient, rising in every direction. Spontaneously, it moves upward, and spontaneously it returns downward. . . . Knowing its essence, one [is freed] from the bonds of existence. . . . In the ear [orally] and in the heart, the description of the gander is to be made known. [Its] call becomes manifest in the throat, [audible] near and far. From the base of the feet to the highest height, the [goddess] named Vm has the form of a ring (kualktim). It is she who, seated in the anus, rises upward until she is absorbed at the End of the Twelve. Thus indeed the gander sports in the midst of a body that is both auspicious and inauspicious.94

Lilian Silburn suggests that it is the serpent’s coiling and straightening that explain its projection upon the subtle body: a venomous serpent, when coiled, is dangerous; straightened, it is no longer threatening. This would be of a piece with the characterization of the kualin as “poison” when she lies coiled in the lower body and “nectar” when she is extended upward into the cranial vault. Or, Silburn suggests, the image of the kualin is one that borrows from the Vedic creatures Ahir Budhnya and Aja Ekapda, or the Puranic ea and Ananta. In fact, the KJñN describes the Goddess’s body as being “enveloped in fire and having the form of Ekapda (i.e., of a serpent).”95 I am more inclined to see the kualin’s origins in the role of the serpent in Indian iconography. Temples and other buildings are symbolically supported by a serpent that coils around their foundations, an image represented graphically by a certain number of Hindu temples in Indonesia. Similarly, images of the Buddha and later of Viu are figured with a serpent support and canopy. Finally, the phallic emblem of iva, the ligam, is often sculpted with a coiled serpent around its base, whose spread hood serves as its canopy. This is a particularly evocative image when one recalls that the kualin is figured in the classical hathayogic sources as sleeping coiled three and a half times around an internal ligam, with her hood or mouth covering its tip. When the yogin awakens her through his practice of postures and breath control, she pierces the lower door to the medial suum channel and “flies” upward to the place of iva in the cranial vault.

4. Transformations in the Art of Love

The theoreticians of post-tenth-century C.E. high Hindu Tantra were especially innovative in their integration of aesthetic and linguistic theory into their reinterpretation of earlier theory and practice. As such, the acoustic and photic registers lie at the forefront of their metaphysical systems, according to which the absolute godhead, which is effulgent pure consciousness, communicates itself to the world and especially to the human microcosm as a stream or wave of phosphorescent light, and as a “garland” of the vibrating phonemes of the Sanskrit language. And because the universe is brought into being by a divine outpouring of light and sound, the Tantric practitioner may return to and identify himself with this pure consciousness by meditatively recondensing those same photemes of light and phonemes of sound into their higher principles.

This is, in the main, a gnoseological process, in which knowing takes priority over doing. In fact, as Alexis Sanderson has argued, one may see in the high Hindu Tantra of the later Trika and rvidy the end of ritual: “since [the] Impurity [that is the sole impediment to liberation] has been dematerialized, ritual must work on ignorance itself; and to do this it must be a kind of knowing.”96 Of course, a similar transformation had already occurred over two millennia earlier in India, in what Jan Heesterman has termed the transformation of sacrifice into ritual:

The “science of ritual” . . . should be rated as a paradigm of what Max Weber called “formal rationality.” Its rational bent becomes apparent when we notice that it is not just to be done but is required to be “known.” What has to be known are the equivalences, the keystone of ritualistic thought, to which the ubiquitous phrase “he who knows thus” refers.97

In a sense, high Hindu Tantra ritualizes—that is, “gnoseologizes”—Kaula sacrifice in the same way that the Brhmaas did the sacrificial system of the Vedic Sahits; and it is worth recalling here that the term “Tantra” originally applied to the auxiliary acts of the ritual complex of a given sacrifice. It is the general and largely unchangeable part of the complex and the same for all sacrifices of the same type.98

With this, we return to the practice of the kmakal, introduced in chapter 4.99 In the high Hindu Tantric context, the ritual component of the kmakal—that is, rajapna, the drinking of female discharge—becomes abstracted into a program of meditation whose goal is a nondiscursive realization of the enlightened nondual consciousness that had there-to-fore been one’s object of knowledge. Through the meditative practice of mantras (phonematic, acoustic manifestations of the absolute) and of mandalas or yantras (photemes, i.e., luminous, graphic, visual representations of the same), the consciousness of the practitioner is uplifted and transformed to gradually become god-consciousness. But what is the nature of the “practice” involved here? It is reduced to knowing, as the most significant rvidy work on the kmakal, aptly entitled Kmakalvilsa (“The Love-Play of the Particle of Desire”),100 makes clear (verse 8): “Now this is the vidy of Kma-kal, which deals with the sequence of the cakras [the nine triangles of the rcakra] of the Dev. He by whom this is known becomes liberated and [the supreme Goddess] Mahtripursundar Herself.”

Yet even as the acoustic and the photic, phosphorescing drops of sound lay at the forefront of high Hindu Tantric practice, there was a substratum that persisted from other traditions, a substratum that was neither acoustic nor photic but, rather, fluid, with the fluid in question being sexual fluid. As we have seen in these earlier or parallel traditions, it was via a sexually transmitted stream or flow of sexual fluids that the practitioner tapped into the source of that stream, usually the male iva, who has been represented iconographically, since at least the second century B.C.E., as a phallic image, a ligam. iva does not, however, stand alone in this flow of sexual fluids. In most Tantric contexts, his self-manifestation is effected through his female hypostasis, the Goddess, whose own sexual fluid carries his divine germ plasm through the lineages or transmissions of the Tantric clans, clans in which the Yogins play a crucial role. In the earlier Kaula practice, it was via this flow of the clan fluid through the wombs of Yogins that the male practitioner was empowered to return to and identify himself with the godhead. It was this that lay at the root of the original practice of the kmakal, the Art of Love.

5. rvidy Practice of the Kmakal

Here I present a detailed account of the multileveled symbolism of the kmakal, as it is found in the primary rvidy sources, in order to demonstrate how the description itself of the kmakal diagram represents a semanticization or overcoding of the Kaula ritual upon which it is based. A word on the meanings and usages of this term is in order, composed as it is of two extremely common nouns, both of which are possessed of a wide semantic field. The simplest translation of the term might well be “The Art (kal) of Love (kma).” Two other important senses of the term kal yield the additional meanings of “Love’s Lunar Digit” or “Love’s Sixteenth Portion.” Earlier, we also saw the use of the term kal in early yogic body descriptions as a subtle force, synonymous with the kualin, and the mother of phonemes.101 Commenting on Abhinavagupta’s Tantrloka (T), Jayaratha (fl. ca. 1225–1275) refers to the kmakal or kmatattva as the “Particle (or Essence) of Love,” a gloss to which I will return.102

Nowhere in the history of these medieval traditions is the kmakal accorded greater importance than in rvidy, which, likely born in Kashmir in the eleventh century, came to know its greatest success in south India, where it has remained the mainstream form of kta Tantra in Tamil Nadu, down to the present day.103 The kmakal is of central importance to rvidy because it is this diagram that grounds and animates the rcakra or ryantra, the primary diagrammatic representation of the godhead in that tradition. Thus verse 8 of the thirteenth-century Kmakalvilsa [KKV] of Puynandantha states that “the Vidy of the Kmakal . . . deals with the sequence of the Cakra [of the rcakra] of the Dev. . . .”104

The rcakra is portrayed as a “drop” (bindu) located at the center of an elaborate diagram of nine nesting and interlocking triangles (called cakras), surrounded by two circles of lotus petals, with the whole encased within the standard gated frame, called the “earth citadel” (bhpura). The principal ritual practice of rvidy is meditation on this cosmogram, which stands as an abstract depiction of the interactions of the male and female forces that generate, animate, and ultimately cause to re-implode the phenomenal universe-as-consciousness. The practitioner’s meditative absorption into the heart of this diagram effects a gnoseological implosion of the manifest universe back into its nonmanifest divine source, and of mundane human consciousness back into supermundane god-consciousness, the vanishing point at the heart of the diagram. In the rvidy system, these male and female principles are named Kmevara and Kmevar, “Lord of Love” and “Our Lady of Love,” a pair we have already encountered in an Indonesian ritual of royal consecration.105

To maintain the image of the drop, as the rvidy sources do, it is appropriate to conceive the entire diagram, with its many “stress lines” of intersecting flows of energy and consciousness, as a diffraction pattern of the wave action initiated when the energy of a single drop, falling into a square recipient of calm water, sends out a set of ripples that interfere constructively and destructively with one another. This, too, appears to be the image the rvidy theoreticians had in mind when they described the relationship of the nonmanifest male and manifest female aspects of the godhead in terms of water and waves. In his commentary on Yoginhdaya (YH) 1.55, the thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Amtnanda (whose teacher, Puynandantha, was the author of the KKV)106 states:

The waves are the amassing, the multitude of the constituent parts of Kmevara and Kmevar. It [the heart of the rcakra] is surrounded by these waves and ripples as they heave [together]. . . . Here, the word “wave” (rmi) means that Paramevara [here, a synonym of Kmevara], who is light, is the ocean; and Kmevar, who is conscious awareness, is its flowing waters, with the waves being the multitude of energies into which they [Paramevara and Kmevar] amass themselves. Just as waves arise on the [surface of the] ocean and are reabsorbed into it, so too the [r]cakra, composed of the thirty-six tattvas . . . arises from and goes [back to Paramevara].107

It is, then, a phosphorescing (sphurad) drop of sound (bindu) that animates this cosmogram and the universe, and into which the mind of the person who meditates upon it is resorbed. This drop is the point located at the center of the rcakra, and the kmakal is a “close-up,” as it were, of this drop. When one zooms in on it meditatively, one sees that it is composed of three or four elements whose interplay constitutes the first moment of the transition, within the godhead, from pure interiority to external manifestation, from the pure light of effulgent consciousness (praka) to conscious awareness (vimara). I now give an account of these constituent elements of the kmakal and the means and ends of meditation upon them, as described in the rvidy and the broader Tantric literature.108

Dirk Jan Hoens has translated kmakal as the “Divine Principle (kal) [manifesting itself as] Desire (kma).” In this context,

the triad of iva-akti-Nda [are given] the name Kmakal. . . . iva and akti are called Kmevara and Kmevar. The kmakal symbolizes the creative union of the primeval parental pair; a pulsating, cosmic atom with two nuclei graphically represented by a white and red dot which automatically produce a third point of gravity. This situation is often represented in graphical form as a triangle. This can be done in two ways: with the point upwards or downwards. . . . A final step is taken when this triad is enriched with a fourth element so as to constitute the graphic representation of the most potent parts of Dev’s mystical body (also in this context she is called Kmakal or Tripursundar): her face, two breasts (the white and red bindus) and womb [yoni]. They are represented by the letter written in an older form akin to the Newari [or Brahmi] sign, or by the ha (the “womb” is often called hrdhakal, “the particle consisting of half the ha,” i.e., its lower part). . . .109

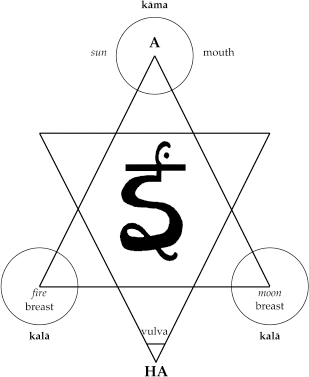

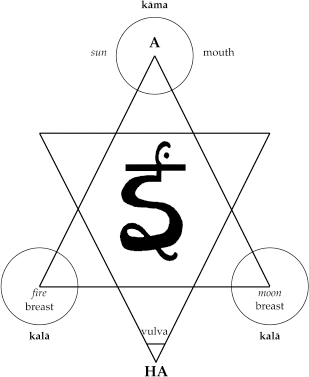

Figure 8.a. Kmakal yantra according to the Yoginhdaya Tantra. Adobe Photoshop image.

In this yantra (fig. 8.a),110 the upturned triangle represents iva, and the downturned triangle, his consort akti.111 At the apex of the upturned iva triangle, we find the Sanskrit grapheme A, which is also the sun and the mouth of the maiden who is the support for this meditation. This is also termed the “medial bindu.” The two bindus or points that form the visarga (the surd Sanskrit phoneme represented by two bindus) are the two base angles of this triangle: they are identified with fire and the moon. They are also the breasts of the maiden. Located between these two and pointing downward is the apex of the downturned akti triangle, which is the yoni of the maiden and the locus of the grapheme HA. Natnandantha, the commentator of the KKV, explains that these elements, taken together, constitute a phonematic rendering of the kmakal, since Kma is Paramaiva (whose desire to create gives rise to the universe), pure effulgence, and the first phoneme, which is A; and Kal signifies reflective consciousness and the last phoneme, which is HA.112

Located in the heart of the hexagon formed by the two intersecting triangles is the kualin, the coiled serpent who here takes the form of the Sanskrit grapheme (which, together with the bindu—the graphic dot over a Sanskrit character that represents the nasalization of a sound—becomes ) However, is also the special grapheme of the supreme rvidy goddess, Tripursundar. Termed the trikha (“having three parts”), it is meditatively viewed as the body of the goddess, composed of head, breasts, and yoni.113 As such, it constitutes a redoubling of the symbolism of the intersecting iva and akti triangles. It is in the form of the grapheme then, that energy, in the coiled form of the kualin serpent, dwells between the bindu and the visarga, that is, between the first and last phonemes and graphemes of the Sanskrit “garland of letters.” Lastly, the kualin is represented in the form of the serpentine grapheme because it is a commonplace of the Hindu yogic tradition that the female akti, which dwells in a tightly coiled form in the lower abdomen of humans, can be awakened through yogic practice to uncoil and rise upward, along the spinal column, to the cranial vault. Here then, the grapheme also represents a yogic process that extends from the base to the apex of the yogic body. Later commentators would find additional correlates to this configuration, identifying the four components of face, breasts, and yoni with four goddesses, four stages of speech, and four cakras within the subtle body.114

There are no less than six levels of overcoding in the Tantric interpretation of this diagram, which reflect so many bipolar oppositions mediated by a third dynamic or transformative element. These oppositions are (1) iva and akti, the male and female principles of the universe in essence and manifestation; (2) the phonemes A and HA, the primal and final utterances of the phonematic continuum that is the Sanskrit alphabet; (3) the effulgent graphemes or photemes representing the phonemes A and HA, here the bindu (a single point or drop) and the visarga (a double point or drop);115 (4) two subtle or yogic “drops,” the one red and female and the other white and male, which combine to form a third “great drop”;116 (5) male and female sexual emissions; and (6) the corporeal mouth and vulva of the maiden upon whom this diagram is projected in Kaula-based practice.

These bipolarities are mediated by the serpentine nexus of female energy, the kualin, who in her yogic rise from the base to the apex of the system is described as telescoping the lower phonemes and graphemes of the Sanskrit garland of letters back into their higher evolutes, until all are absorbed in the bindu, the dimensionless point at which all manifest sound and image dissolve into silence and emptiness, in the cranial vault. Also bearing a yogic valence in this diagram and its interpretation are the elements sun, moon, and fire. Identified here with the upper bindu and lower visarga, respectively, these also represent the three primary channels of yogic energy, the right, left, and central channels, respectively.

Finally, we also detect a sexual substrate to this diagram. First of all, the first member of the compound is, after all, “kma,” erotic love, and the name of the Indian Eros or Love, whose arts are described in works like the Kma Stra. Second, the ritual support of this meditation is a maiden’s naked body. Of course, in high Hindu Tantra, the flesh-and-blood maiden substrate is done away with, with the abstract schematic visualization sufficing for the refined practitioner. Yet she remains present, just beneath the surface of her geometric and semantic abstraction, as such was effected in these later cosmeticized traditions. In a discussion of the kmakal, the Yoginhdaya describes the two bindus that make up the corners of the base of the iva triangle and the breasts of the maiden as red and white in color. Here, the white and red drops are “iva and akti absorbed in their movement of expansion and contraction.”117 Clearly, the bindus so described are not abstract points but rather subtle drops of sexual fluids, that is, male semen and female uterine blood.118 Thus, the bindu as photic grapheme (dimensionless point of light) and the bindu as acoustic phoneme (dimensionless vibration, particle of speech) are overcodings of the abstract red and white bindus of the subtle body physiology of yogic practice, which are in turn overcodings of concrete drops of male and female sexual fluids (particles of love). These unite, in the upper bindu at the apex of the triangle, in the mouth (mukham) of the maiden, into a mahbindu, a “great drop.” We are reminded, however, that her mouth, the apex of the upturned iva triangle, is “reflected” in her vulva, the apex of the downturned akti triangle.119 Furthermore, as we have noted, a woman’s oral cavity is reflected, redoubled in her vulva, her “nether mouth.”

The fact that these divine principles were transacting in something more concrete than graphemes and phonemes is made abundantly clear even in these scholasticist, semanticizing sources. On the basis of terminology alone, we can see that the conceptual matrix is sexual. The absolute flashes forth, in phosphorescent effulgence (sphuratt; ullsa). It expands as a phosphorescent wave, a welling, a swelling (sphurad-rmi)120 . . . thereby manifesting the cosmos made up of the thirty-six metaphysical categories (tattvas), from iva down to the element earth. . . . The Goddess is luminously conscious (prakmarana). . . . She is “throbbing incarnate” (spandarpin), being immersed in bliss (nanda). . . . The cosmos is her manifest form, but, though shining as the “essence of divine loveplay” (divyakrrasollsa), the Absolute is pure undivided light and bliss.121

The subliminal sexual referents of this abstract image of the “Art of Love” were not entirely lost on the rvidy theoreticians. That they were aware of such is made clear from a debate that raged within the school concerning the relative legitimacy of conventional (samaya) meditation on the kmakal as opposed to the Kaula form of the same. It was in this latter (and earlier) case that a maiden’s naked body was used as the meditational substrate.122 A number of rvidy commentators, led by the venerable seventeenth-century master Bhskararya, insisted on the literal use of this meditation support, together with the referents of the five M-words, all of which smacked of the Kaula practices.123 Finally, the names of “Our Lord and Lady of Love,” in addition to their associations evoked above, are also identified, in the pre-fourteenth-century Klik Pura, with the pha of Kmkhy, whose sexual associations are legion in Tantric traditions.124

Elsewhere the worship of the sixteen Nity goddesses who constitute the Goddess’s retinue, and which rvidy tradition identifies with the sixteen lunar tithis,125 includes offerings of meat and alcohol. It is especially the names of these sixteen Nity goddesses that constitute the most obvious bridge between this and the earlier Kaula version of the same, given that these sixteen names are identical to those of the sixteen kal-aktis of the ilpa Praka.126 In rvidy sources these sixteen form the immediate entourage (varaa) of the Goddess, to whom sacrifices are to be offered, either in the central triangle or between the sixteen-petaled lotus and the square of the rcakra. In other words, they occupy the same place in these sources as the sculpted images of the “eightfold practice of the kmakal” occupied on the early Tantric temples of Orissa.127 The sole variation between the two lists lies in the name of the first akti: she is Kmevar in rvidy sources and Kme in the Kaula diagram.128

6. Mantric Decoding and Kmatattva in the Later Trika

It was the Kashmiri theoreticians, specifically Abhinavagupta and his disciple Kemarja, who were most responsible for the semanticization of Kaula ritual into a form acceptable to the Hindu “mainstream,” to married householders, seekers of liberation, for whom the antinomian practices of the former were untenable. Here, in the socioreligious context of eleventh-century Kashmir, these reformers of the Trika sought to win the hearts and minds of a conformist populace by presenting a cleansed version of Kaula theory and practice, while continuing to observe the original Kaula rites in secret, among the initiated virtuosi. This trend of the progressive refinement of antinomian practice into a gnoseological system grounded in the aesthetics of vision and audition culminates in the rvidy tradition. Quite significantly, it is the image of a drop (bindu) that recurs, across the entire gamut of Tantric theory and practice, as the form that encapsulates the being, energy, and pure consciousness of the divine; and so it is that we encounter a multiplicity of references to drops of fluid, drops of light, drops of sound, and drops of gnosis. The language of phonemes and photemes, of mantras and yantras, make it possible for practitioners of high Hindu Tantra to discuss, in abstract, asexual terms, what was and remains, at bottom, a sexual body of practice. Through it, particles of love become transformed into particles of speech.

This is the explicit teaching of the (twelfth-century?) Vtlantha Stra (VNS) and its commentary by the sixteenth-century Anantaaktipda,129 according to which the mystic is effortlessly initiated, without the aid of external gurus or masters, by his own divinized powers of cognition, called “Yogins.”130 In the sixth verse to his commentarial introduction, Anantaaktipda evokes the “stras emitted from the mouth of the Yogin,” and, in fact, each of the aphoristic teachings of this text is, according to him, presented by an internal Yogin. It is in this way that that the overtly sexual language of the fifth stra, “From the sexual union of the Siddha and the Yogin the great mingling (mahmelpa) arises,”131 is entirely sublimated and semanticized by Anantaaktipda:

The expression “Siddha-Yogin” designates those who are Yogins and Siddhas, that is, the divinities of the senses and the objects of the senses. Their close contact is the “sexual union” of the two: the coming together of object [what is grasped] and subject [grasper]; or, again, their mutual and perfect embrace. By virtue of this embrace, an uninterrupted “great mystic union” (mahmelpa) occurs; that is, a sudden awakening or fluid equilibrium (mahsmarasya) which takes place constantly and everywhere in the ether of transcendent consciousness, when the duality of subjectivity and objectivity has melted away.

Here, the ritualized and sexualized Kaula “minglings” (melpas) of flesh-and-blood Yogins and Siddhas that once took place on isolated hilltops on new moon nights now occur at all times within the “heart” of the enlightened Tantric practitioner, where they form the entourage of Bhairava-as-pure-consciousness and are characterized by their “extremely subtle vibrational activity.”132 In the context of these semanticized renderings, it is mantras that render one’s practice effective, containing in their very sound structure a mystic gnosis that, in a gnoseological system, is liberating. In every Tantric tradition, mantras are phonematic embodiments of deities and their energies, such that to know the mantra, and to be able to pronounce and wield it correctly, becomes the sine qua non of Tantric practice.133 These mantras, nondiscursive agglomerations of syllables, are entirely meaningless to an outsider; yet knowledge of their arcane meaning and, perhaps more importantly, the very divine energies embedded in their phonematic configuration render them incalculably powerful in transforming the practitioner into a “second iva” and affording him unlimited power in the world.

It is for this reason that mantras are themselves a matter of great secrecy and thereby subject to a wide array of security measures in their use and transmission.134 First of all, a mantra will generally be pronounced silently or inwardly, so as to not fall upon the wrong ears. When it is transmitted orally, as in the case of the initiation of a disciple by his teacher, this process is called “ear-to-ear” transmission (kart karopadeena). There exists, however, a massive textual corpus (called mantrastra) devoted to the discussion of secret mantras, which, in order to maintain the secrecy of these powerful, sect-specific utterances, are only given in code.135 In these sources, mantric encoding and decoding can take a number of forms, including the embedding and “extraction” (uddhti) of a mantra136 from its concealment in the midst of a mass of mundane phonemes, through one or another sort of cryptogram,137 or through more simple strategies of writing the mantra in reverse order, interchanging the syllables of a line, substituting an occult term for a phoneme, et cetera. However, we find in the texts of mantrastra, as well as in commentaries on texts in which mantras are given in code, “skeleton keys” that explain how to construct the mantric cryptograms, sets of equivalents for decoding occult terms, and so on. Here again, we find that a strategy of secrecy—implied in the encrypting of mantras—is undermined, in this case, by written instructions for their decryption.

It is nonetheless essential to note here that in high Hindu Tantra the knowledge and manipulation of extremely complex mantras are, by simple virtue of the fact that they are utterances in the Sanskrit tongue, the privileged prerogative of the Indian literati, who are, nearly by definition, comprised of the brahmin caste.138 For this reason, the likelihood of their being decrypted and used by non-brahmins is minimal—and high Hindu Tantra has been, from the outset, a mainly brahmanic prerogative. Now, Paul Muller-Ortega has argued, quite cogently, that the concealment of mantras through encoding/encryption, followed by their “revelation” through decoding/decryption, is of a piece with the theology of high Hindu Tantra, which maintains that these are the two modes of being that characterize the godhead in its expansion and contraction, into and out of manifest creation.139 That is, the decrypting of the mantra is, in and of itself, a mystic experience, a powerful communication of the Tantric gnosis to the initiate.

In high Hindu Tantra, the acoustic practice of the mantra flows directly into, or is simultaneous with, the visual practice of the mandala. This we have already seen in the context of the kmakal diagram: the bindus are simultaneously mantric utterances and photic graphemes. The Goddess is said to have a “body composed of letters” (lipitanu), which renders the act of reading them an audiovisual voyage of sorts through her body. Another grapheme will aid us in moving from this discussion of mantric encoding and encryption to an earlier time in the history of Hindu Tantra, when secrecy seemed not to have been such a vital and vexing issue. This is the phoneme E, whose grapheme, in the Sanskrit alphabet, more or less has the form of a downturned triangle. Because of its form, E is considered to be the privileged grapheme of the Goddess, the site of creation and joy, because it is identified as the “mouth of the Yogin.” As before, the term “mouth” here refers to the Goddess’s or Yogin’s vulva, which is called a site of creation and joy and “beautiful with the fragrance of emission”140 because, in early Hindu and Buddhist Tantra, one was reborn, re-created through initiation, and was assured the joy of liberation through the nether mouth of the Yogin.141

Now, it is true that the Goddess, as the source of all mantras, is described in the high Hindu Tantric sources as bhinnayoni,142 “she whose vulva is spread”—but the question then arises as to how a woman embodying the Goddess would have been able to transmit mantras, sound formulas, through her vulva. This depiction of the Goddess is in fact found in a discussion, by Abhinavagupta, of Mlin, the goddess identified with the energy of intermediate speech (madhyam vc) in the form of the “Garland of Phonemes”: “And this [Little Mother], by banging together with the Mass of Sounds, becomes the Garland of Phonemes, whose vulva is spread.”143

The fluid dynamic of this complex is made explicit in Kubjik traditions, which locate the Goddess’s yoni at the level of the End of the Twelve of the subtle body, impaled there upon a subtle iva liga that rises out of the cranial vault.144 This yoni is simultaneously a “womb of mantras” and the nexus of the energy of transmission of gnosis, in the form of the Goddess’s “command” (jñ). As the source of mantras, the triangle is subdivided into fifty smaller triangles, nested inside of it, each of which contains a Sanskrit phoneme. “Each letter is worshiped as a Bhairava or a Siddha. Each one of them lives in his own compartment, which is itself “a yoni said to be ‘wet’ with the divine Command (jñ) of the energy of the transmission that takes place through the union they enjoy with their female counterparts.”145

The acoustic kmakal (or kmatattva), whose practice Abhinavagupta also describes is, once again, the visarga, comprised of two bindus, as found in the rvidy kmakal.146 “Therefore, the venerable Kulagahvara [‘Cave of the Clan’] states that ‘this visarga, which consists of the unvoiced [avyakta] ha particle [kal],147 is known as the Essence of Desire [kmatattva].’” Still quoting from this lost source, he continues: “[It is] the unvoiced syllable which, lodged in the throat of a beautiful woman, [arises] in the form of an unintentional sound, without forethought or concentration [on her part]: entirely directing his mind there [to that sound, the practitioner] brings the entire world under his control.”148 Here, Abhinavagupta’s bridge, between external ritual (if not sexual) practice and internalized speech acts, is the sound a woman makes while enjoying sexual intercourse—a barely articulated “ha, ha, ha.”149 It is this particle of speech (kal) that is the essence of desire or love: in other words, the “ha” sound of the visarga is the semanticization of sex in Abhinavagupta’s system. However, as in the case of rvidy, the “practice” of the kmakal is reduced to meditative concentration, this time upon a syllable. Ritual doing has been reduced, once again, to a nondiscursive form of knowing. However, the presence of a sexual signifier again orients us back in the direction of a Kaula substratum that involved ritual practices of a sexual order.

7. The Masculinization of Tantric Initiation

In chapters 3 and 4, I presented a wealth of data to argue that the “insanguination” of the male initiate by a Yogin lay at the heart, if not the source, of Kaula initiation and ritual. At the same time, many of these rituals also brought a male actor into play in the person of the teacher or master (guru or crya),150 with the combined sexual emissions of the pair transforming the initiand from an undetermined biologically given pau into a kulaputra, a son of the clan. As one moves forward in time, and out of the Kaula context and into more conventional forms of Tantra, the role of the Yogin becomes increasingly eclipsed by that of the male master. In fact, this shift toward “guru-ism” is one of the most fundamental dynamics in the development of later Tantra. The male guru gives birth to a new member of the Tantric order by inseminating his novice with male sexual fluid, which is nothing other than the seed of the male iva himself.

This transmission is termed initiation by penetration (vedha[may] dk) in a number of contexts,151 with the next move—the total sublimation of the sexual drop (bindu) or seed (bja) into a seed mantra (bja-mantra)—occurring in nearly every high Hindu Tantric tradition. iva, the divine revealer of the Liga Pura, states that “initially my eternal command (jñ) arose out of my mouth.”152 Mark Dyczkowski links this statement to a description found in an early Kaula work, the Kularatnoddyota, in his discussion of the term jñ, which is reproduced in chapter 3. In this latter text, the guru initiates the disciple by literally transmitting the “command” to him through the recitation of mantras, at the level of the jñ cakra, the “Circle of Command.”153 In his account of vedhadk, Abhinavagupta states that the disciple should press himself against the master, who, in order to effect a perfect fusion (samarasbhavet), should be mouth to mouth and body to body with him.154

In fact, rituals of male-to-male transmission or initiation predate aivism and Kaula traditions by at least two millennia. They constitute the Vedic norm, as it were, as evidenced in the Atharva Veda (AV) statement that “the teacher, when he initiates his pupil, places him, like a fetus, inside of his body. And during the three nights [of the initiation], he carries him in his belly. . . .”155 The B hadrayaka Upaniad (1.5.17) describes the transmission (sampratti) of breath from a dying father to his son in similar terms: “When he dies to this world, he penetrates his son with his breaths. Through his son, he maintains a support in this world, and the divine and immortal breaths penetrate him.” Finally the Kautaki Upaniad (2.15) anticipates Abhinavagupta’s instructions for vedhadk by at least twelve hundred years: “When the father is at the point of dying, he calls his son [to him]. . . . [The] father lies down, dressed in new clothing. Once he has arrived [there], the son lies down upon him, touching [his father’s] sense organs with his [own] sense organs.”156

As Paul Mus argued over sixty years ago, the guiding principle of these ancient sources was “not that one inherits from one’s [father]; rather, one inherits one’s father.”157 This was not, however, the implicit or explicit model of initiation in the later Tantric traditions. Rather than being the extension of a preexisting brahmanic mode of male self-reproduction, this was rather a reversal and masculinization of the Kaula model of heterosexual reproduction. That is, the Tantric vedha[may] dk and other initiations and consecrations self-consciously removed the feminine from the reproductive process, usually by internalizing and semanticizing her as the guru’s akti, the “mother of the phonemes” and “fire stick of the mantras” passively transmitted from the guru’s mouth into that of his disciple.158 So, for example, in his general introduction to Tantric initiation in the T, Abhinavagupta quotes the Ratnaml Tantra in stating that when the master places the mlin (mantra) on the disciple’s head, it’s effect is so powerful that it makes him fall to the ground.159 Here as well, the Yogin—however instrumentalized she may have been in the Kaula rites in which the silent discharge from her nether mouth transformed an initiate into a member of the clan—has now been semanticized out of existence. As I argued in chapter 3, advances in Indian medical knowledge were such that a woman’s contribution, in the form of her “female discharge,” to the conception of a fetus, was well known by the time of the emergence of the Kaula rites. This understanding of the biology of reproduction, so important to the development of the Yogin Kaula, was therefore consciously censored and sublimated in the initiation rites of later high Hindu Tantra. This paradigm nonetheless persists in the Bengali traditions of the dk guru (master of initiation) and the k guru (teaching master). In both Sahajiy Vaiava and Bul traditions, the former, who is a male transmitter of mantras, plays a secondary role to the latter, who is female and whose “teaching” is received through her sexual emissions.160

In these rituals and their mythological representation, the guru inseminates his disciple by spitting into his mouth,161 a masculinized alloform of transmitting a chew of betel between mouths.162 Curiously, this type of transmission also becomes transposed into Indian Sufi hagiographical literature from the time of the Delhi Sultanate:

Now there was one man who had that very day become a disciple of the Shaykh; he was called Jaml-al-dn Rvat. The Shaykh told him to go forth and give an answer to the [unnamed] Jog’s display of powers. When Jaml-al-dn hesitated to do so, the Shaykh called him up close to him and took some pn out of his own mouth and placed it with his own hand in Jaml-al-dn’s mouth. As Jaml-al-dn ate the pn he was overcome by a strange exaltation and he bravely set out for the battle. He went to the Jog. . . . When the Jog had exhausted all his tricks he then said, “Take me to the Shaykh! I will become a believer.” . . . At the same time all the disciples of the Jog became Muslims and made a bonfire of their religious books.163

Another tradition that blends Sufi and Tantric imagery, if not practice, is that of the Nizarpanthis of western India, whose “way of the basin” ritual was described in chapter 3.164 Here, it will be recalled that the term pyal is used by Nizarpanthis for the mixture of sperm and chrma that all participants consume at the end of this ritual. This terminology appears to have been inspired by Sufi traditions, in which “taking the cup” (piyl len), that is, sharing a drink of milk with the master, is a transformative moment in initiation rites. However, here as well, the “milk” in the cup may have originally been the semen of the initiating pr, diluted in water.165

8. Prescriptive Dreams and Visions