1. ‘From this day forth, the Ukrainian People’s Republic becomes independent, subject to no one, a Free, Sovereign State of the Ukrainian People.’ The Central Rada declares independence, Fourth Universal, 9 January 1918.

NATIONAL REVIVAL

2. Heorhiy Narbut designed the Ukrainian coat-of-arms, stamps and banknotes as well as this cover of the cultural journal Nashe Mynule, which means ‘Our Past’.

3. An independence rally in 1917 on Khreshchatyk, Kyiv’s main street – also the site of the Maidan demonstrations in 2014.

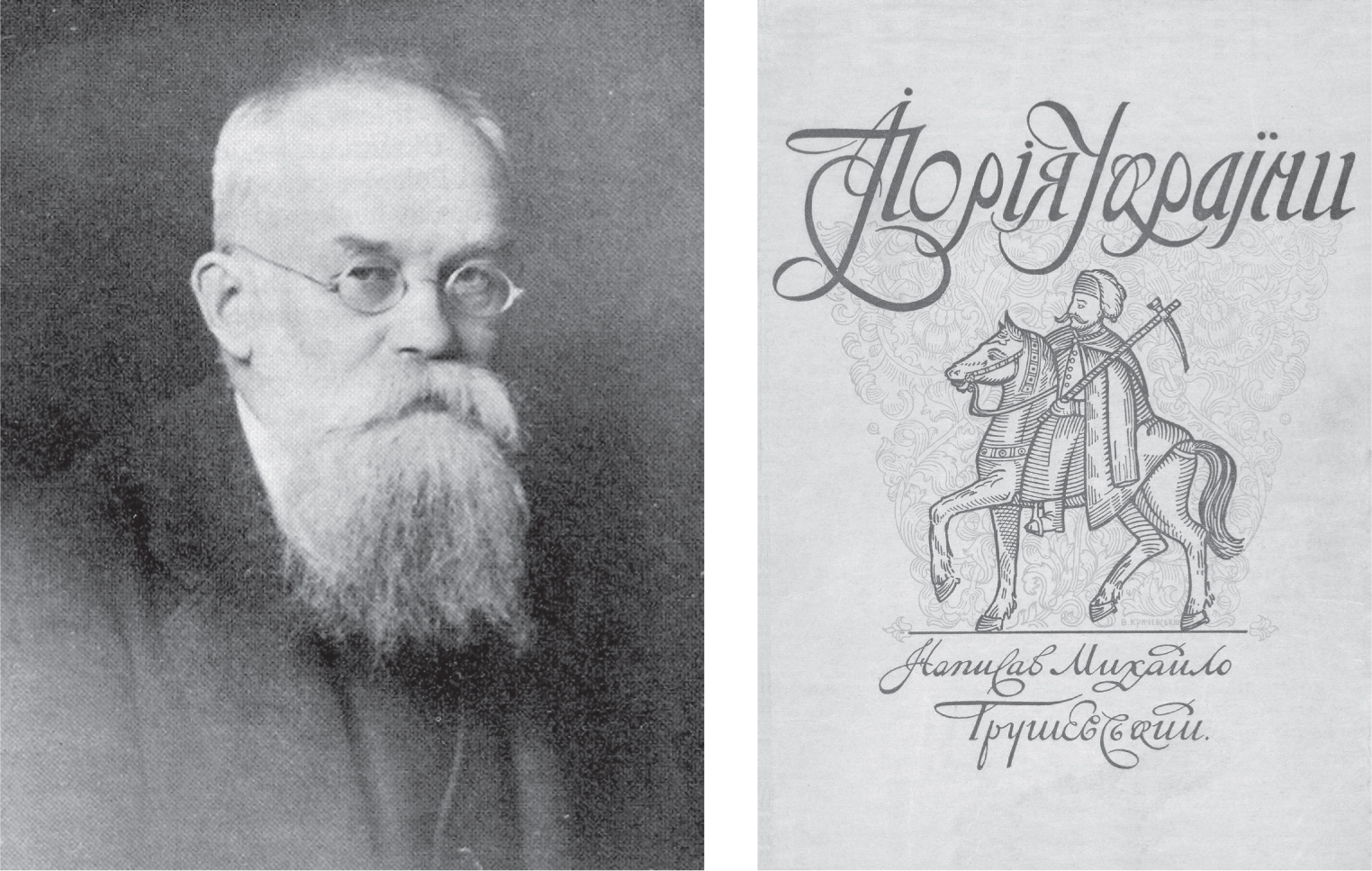

4-5. Mykhailo Hrushevsky, one of the leading figures in the Ukrainian national revival, and the cover of his landmark History of Ukraine, published in 1917.

NATIONALISTS AND ANARCHISTS

6. Symon Petliura (centre right), commander of the Ukrainian Directory, with Polish leader Józef Piłsudski (centre left), Stanislaviv, 1920. Memories of this Ukrainian–Polish alliance haunted Stalin for many years.

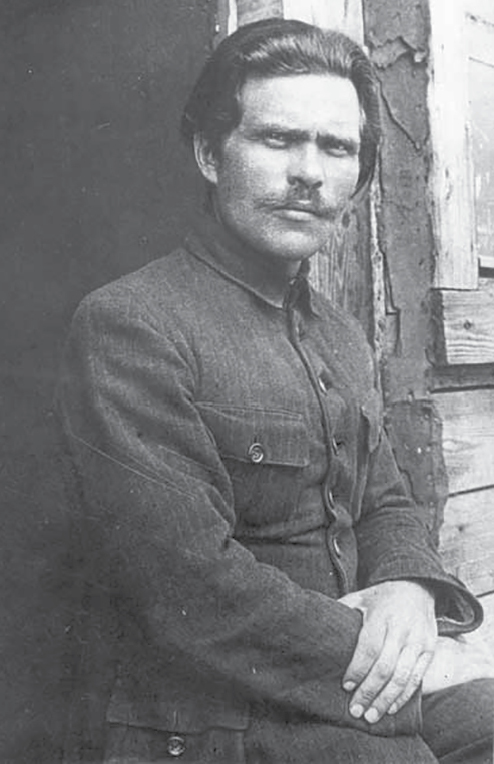

7. Nestor Makhno, whose anarchist Black Army fought Ukrainian, Bolshevik and White armies alike.

8. Pavlo Skoropadsky (centre), who took the Cossack title hetman and ruled Ukraine with German backing in 1918.

COMMUNISTS

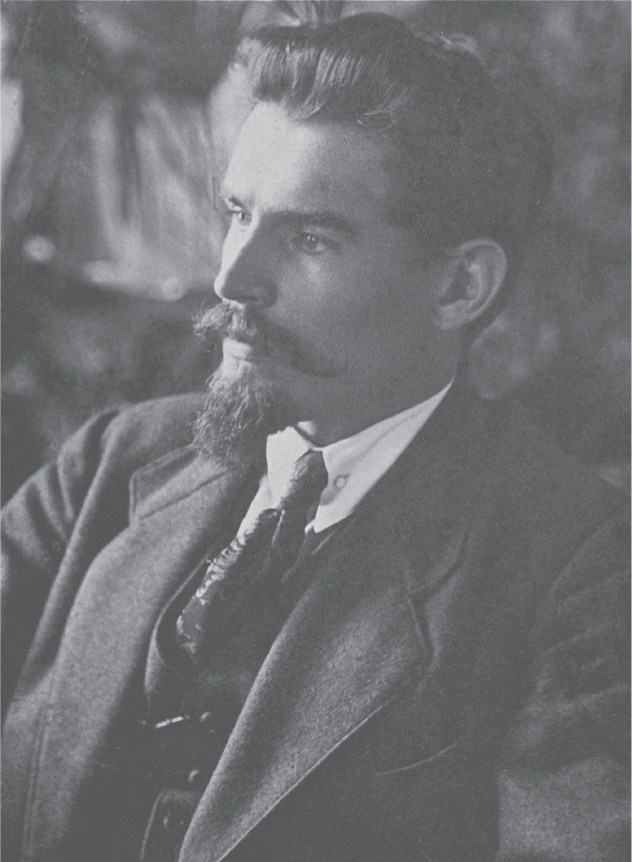

9. Oleksandr Shumskyi, the Borotbyst party leader who joined the Bolsheviks before being expelled for nationalism. Arrested during the famine.

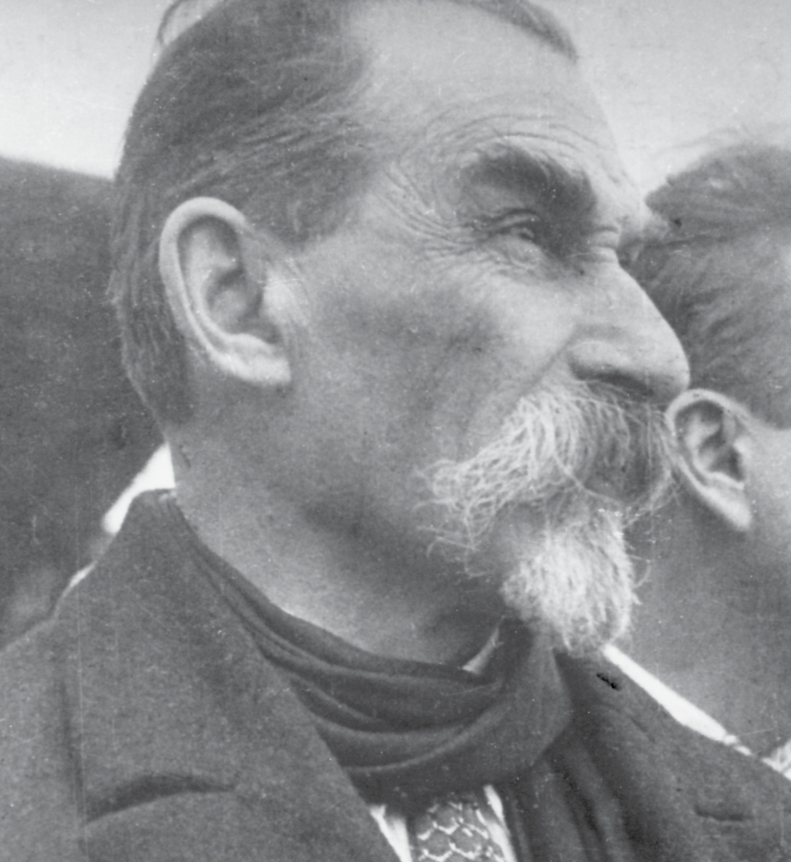

10. Mykola Skrypnyk, the leading ‘national communist’. Killed himself during the famine.

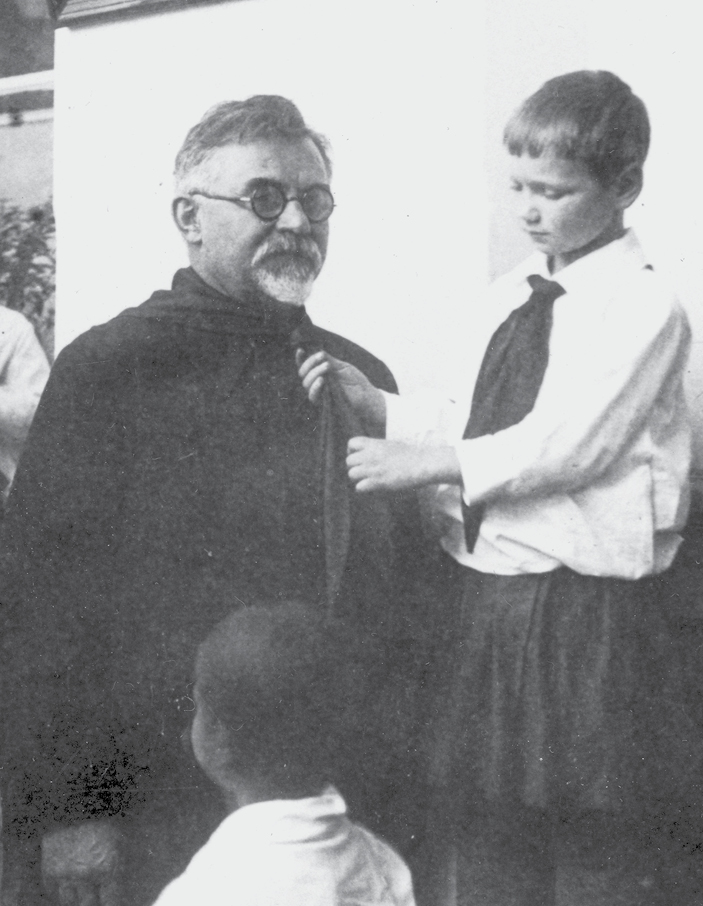

11. Hryhorii Petrovskii with a member of the ‘Pioneer’ youth group, putting on a Pioneer tie. Leader of the Ukrainian republican government during the famine.

12. Vsevelod Balytsky, OGPU. Leader of the Ukrainian secret police during the famine.

DE-KULAKIZATION

13. An auction of ‘kulak’ property.

14. A ‘kulak’ family on their way to exile.

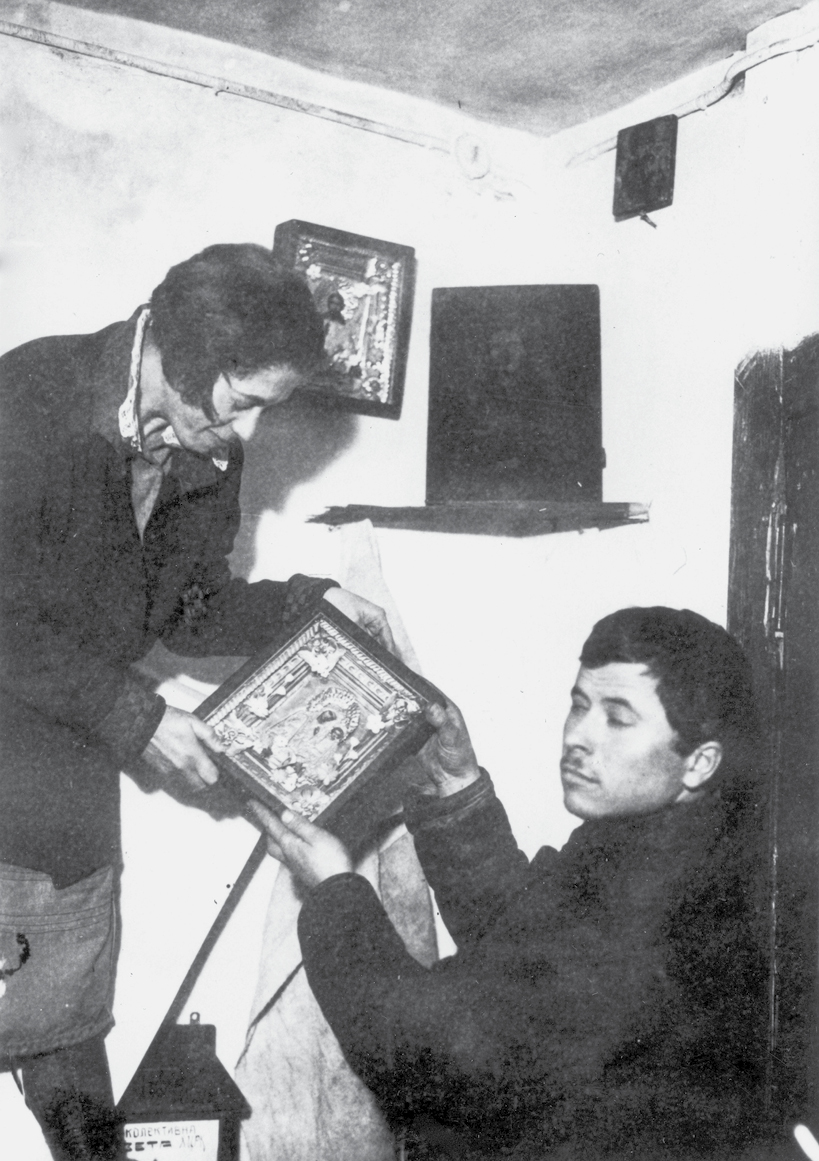

15. Confiscating icons, Kharkiv.

16. Discarded churchbells, Zhytomyr. They were later melted down.

17. Poor peasants beside the ruins of a burned house.

18. What collectivization was supposed to be: women voting to join a collective farm.

COLLECTIVIZATION, OFFICIAL VERSION

19. Peasants listening to the radio during a break from fieldwork.

20. Peasant family reading Pravda.

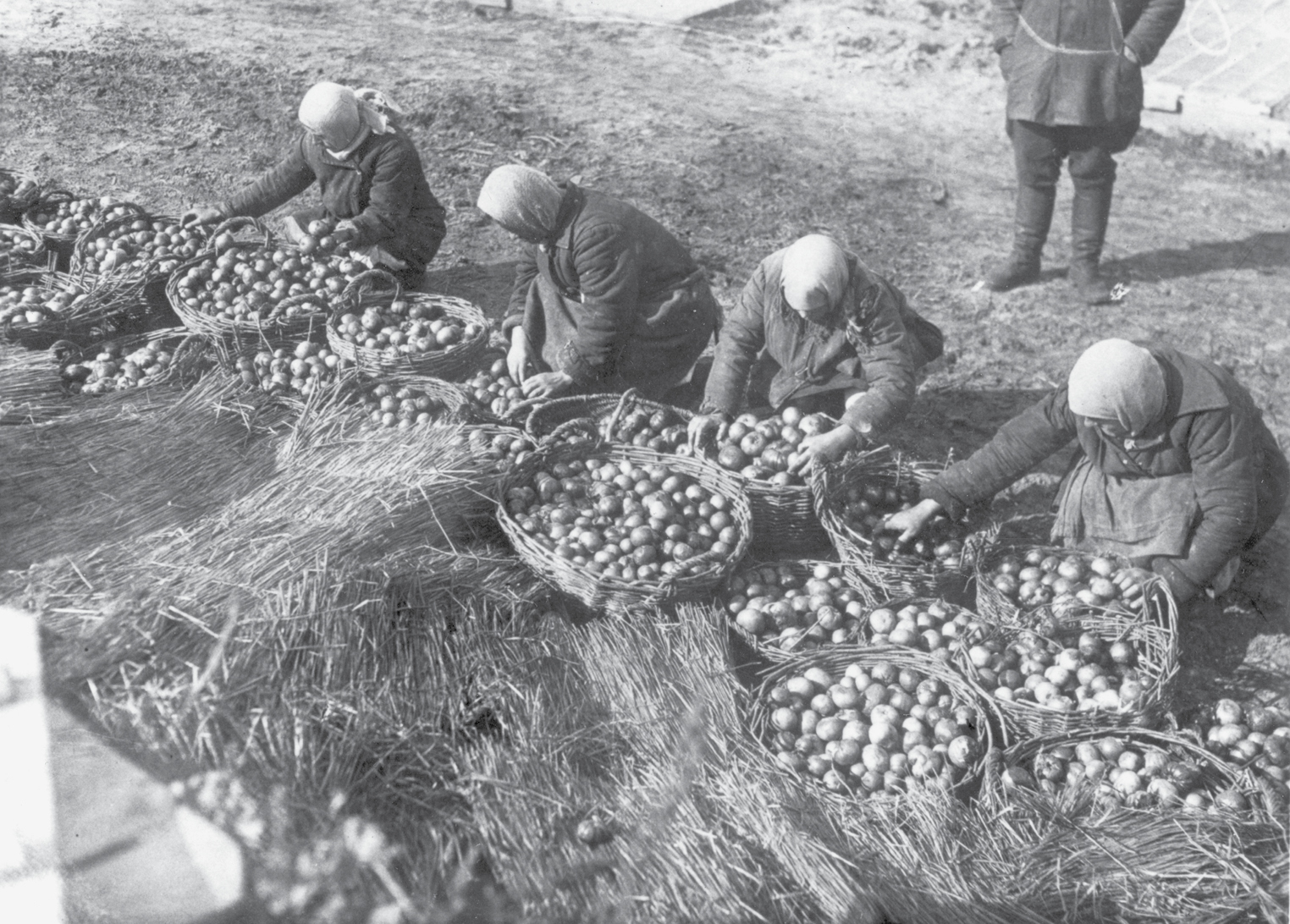

21. A bountiful tomato harvest.

22. Workers from a local factory ‘voluntarily’ help bring in the harvest.

GRAIN REQUISTIONS

23. An activist brigade finds grain buried underground. The leader is holding one of the long iron rods used in the searches.

24. An activist brigade shows off sacks of grain and corn they’ve discovered.

25. Guarding the fields on horseback.

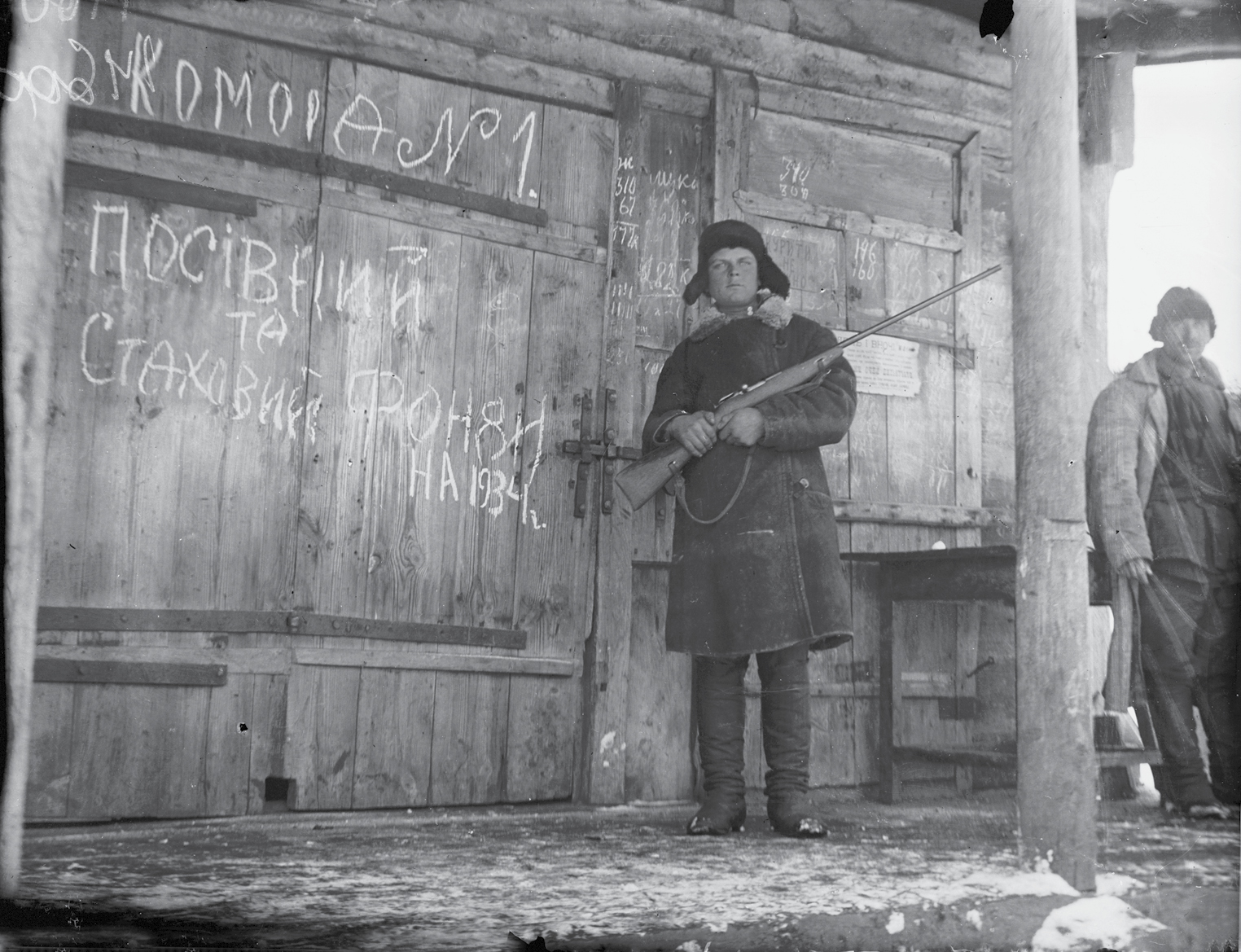

26. Guarding the grain stores with a gun.

FAMINE, KHARKIV PROVINCE, SPRING 1933

27. Peasants leaving home in search of food.

28. An abandoned peasant house.

29. Starving people by the side of a road.

30. A starving family on waste ground.

31. Peasant girl. One of Alexander Wienerberger’s most famous photographs.

32. Breadlines in Kharkiv.

33. Breadlines in Kharkiv.

FAMINE, KHARKIV, SPRING 1933

34.

35.

36.

37.

THE AFTERMATH

38. Weinerberger took this photograph of the same man – alive and then dead.

39.

40. Two photographs taken by Mykola Bokan, Baturyn, Chernihiv province, and preserved in his police file. The first, from April 1933, includes the caption ‘300 days without a piece of bread’.

41. Bokan’s second photograph, July 1933, includes a memorial to ‘Kostya, who died of hunger’. Bokan and his son were arrested for documenting the famine. Both died in the Gulag.

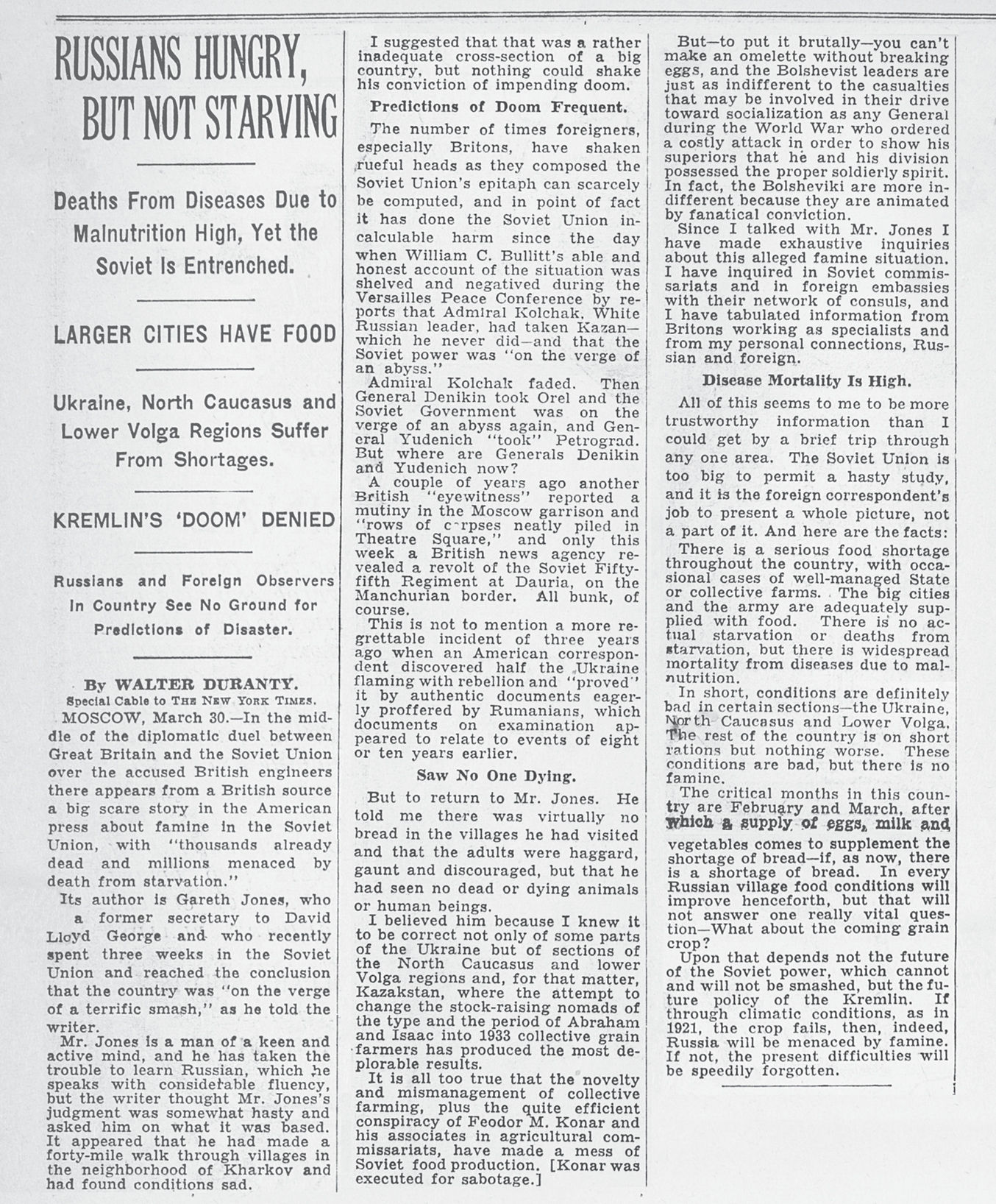

THE WESTERN PRESS

42. Gareth Jones, Evening Standard, 31 March 1933.

43. Walter Duranty (centre right) dining sumptuously in his Moscow apartment.

44. Walter Duranty, The New York Times, 31 March 1933.

45. The Victors: Kaganovich, Stalin, Postyshev, Voroshilov, 1934.

46. The Victims: a mass grave outside Kharkiv, 1933.