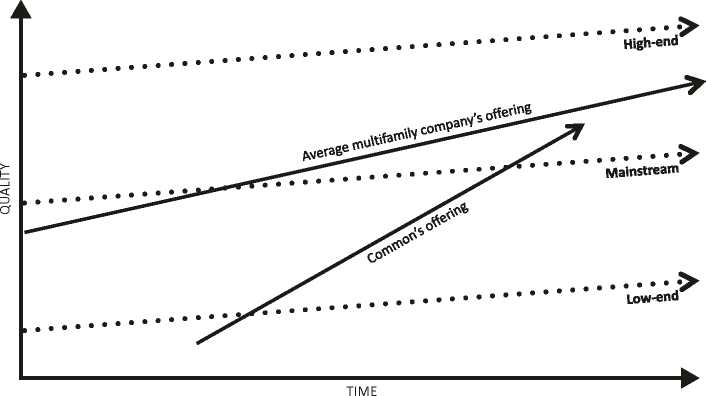

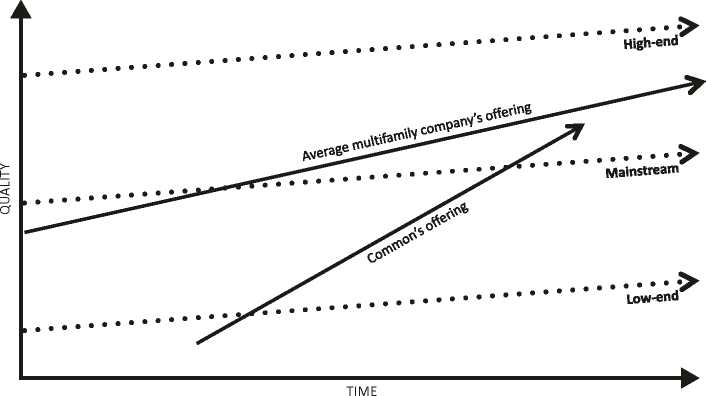

Fig. 15.1 The trajectory of disruptive innovation in the multifamily sectorcccii

Forces Reshaping Housing

In 2006, the living room of Chris Bledsoe became a makeshift bedroom. The guest, in this case, did not arrive through Airbnb. Andrew, Chris’s younger brother, just moved to the city and needed a place to stay. After a few weeks, the couch became uncomfortable and Chris encouraged Andrew to get an apartment of his own. A few additional weeks later, Chris provided the necessary guarantees for a lease on a one-bedroom apartment and Andrew moved out.

But the brothers had a plan. To help pay the rent, Andrew decided to bring in sub-tenants. He used a pressurized wall system to split the living room into two tiny but private rooms and posted a short ad on Craigslist. Within 48 hours, nearly 90 people responded to the ad.

Most of the respondents were not travelers. They were living in New York but were either unable to or uninterested in signing a proper lease. The “uninterested” were entrepreneurs or corporate employees working on uncertain projects, international students who did not have the local credit score required to sign a lease, recent divorcees who had to figure out their next steps, and even empty nesters who sold their home and planned to spend several months a year elsewhere. The “unable” applicants had stable jobs and relationships but could not afford to live alone and did not manage to find a roommate who aligned with their move-in date, budget, and living habits.

All the applicants were happy to pay a premium for a very humble room. They valued the fact that everything was ready for them—furniture, kitchen utensils, Wi-Fi. They also valued the absence of a formal application process,

© The Author(s) 2020 147

D. Poleg, Rethinking Real Estate, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13446-4_15

a broker to pay to, or an inscrutable lease from an often-inscrutable landlord. Facing such overwhelming demand, Andrew and Chris realized they were onto something. In 2015, they launched Ollie (a play on “all inclusive”) to try to provide a more intentional and code-compliant solution at a much larger scale.

Ollie’s first step was to join forces with the developers of Carmel Place, an experimental building in Manhattan’s Kips Bay neighborhood. As part of Mayor Bloomberg’s plan to experiment with new solutions for the city’s growing number of small households, Carmel Place was granted several planning exceptions that allowed for smaller units and higher density, featuring 55 micro-studios that ranged from 260 to 360 square feet in total size (compared to the 400 minimum usually required). Carmel Place was built modularly, developed by Monadnock Development, designed by nARCHITECTS and outfitted with unique space-saving furniture from Resource Furniture. Ollie joined late in the development process but managed to make an impact on how units were fit out and how the building was positioned, leased, and operated.

It was at Ollie’s second New York project that a new real estate model started to emerge. The company partnered with Simon Baron, a real estate development company, to affect the design of Alta, a new 43-story residential tower in Queens. Fourteen floors in the building were dedicated to coliving, with two- and three-bedroom units designed, furnished, and serviced in a way that made them easier to share with unrelated individuals. With 422 rooms in 169 shared apartments, Alta was the largest ground-up coliving project ever built in the U.S. (Table 15.1).

Ollie’s role at Alta is similar to that played by hotel brands. The floors operated by the company have been laid out according to unique specifications made by Ollie’s in-house design and architecture teams. Ollie handled the way units were furnished and stocked, down to the paper towel holders and kitchenware. Ollie provides weekly housekeeping with linen and tower service to all the coliving units and replenishes the supply of toilet paper, dish soap, body wash, conditioner, and shampoo.

All Ollie residents have access to Alta’s amenity network including two rooftop lounges, a coworking space, gym, pool, yoga room, and golf simulator.

Table 15.1 Alta unit mix

|

Apartments |

Bedrooms | |

|

Conventional (floors 17–42) |

297 |

367 |

|

Coliving (floors 2–16) |

169 |

422 |

|

Building total |

466 |

789 |

Ollie conducts regular community events, both in and out of the building. Ollie also provides a digital layer, including an app that allows residents to submit maintenance requests, schedule cleanings, book building amenities, receive package notifications, and keep track of the building’s busy schedule of community activities.

On the distribution side, Ollie’s website generates about 80% of the leads to the building’s coliving units, according to CEO Chris Bledsoe.ccxcix Ollie also operates a website that helps residents identify an ideal roommate. The app, called Bedvetter, provides each member with a questionnaire and connects people based on their move-in date, budget, lifestyle, and personal habits. As of June 2019, Bedvetter helped “create” over 200 shared households. Once matched, roommates sign a standardized lease agreement. Other roommate matching solutions such as Nooklyn and Roomi have also grown in popularity in recent years, but Ollie is the first to integrate the process into a comprehensive residential offering.

Ollie’s involvement helped Alta improved the project’s overall financial results. Based on 90% of the coliving units leased by June 2019, the areas of the building operated by Ollie achieved rental premium of about 45% compared to the building’s traditional units. This translates into a 30% increase in net operating income (NOI) per square foot, net of Ollie’s incremental expenses and management fees.

Ollie’s typical arrangement with property owners is also reminiscent of hotel franchisors. The company’s management fees are based on a percentage of rent, with bonuses based on pre-agreed benchmarks, and additional fees for Ollie’s tech services and lead generation. In 2019, Alta’s developer managed to replace the building’s construction loan with permanent financing from Société Générale and Deutsche Pfandbriefbank, reflecting the confidence of traditional lenders in this new coliving operating model for residential buildings.ccc

Dozens of coliving projects by operators such as Ollie, Common Living, Medici Living, and Starcity have proved that the model can deliver superior financial results. But many in the industry still question the overall potential of the coliving market and see it as a niche product. We believe that demand for coliving is driven by demographic and technological changes that impact a significant share of the population. More importantly, it would be a mistake to assume that coliving’s operating model applies only to the customers it currently serves. The model’s evolution points to a bigger shift in the way all residential assets are operated. Let’s see how.

At the same time that Ollie was working on ground-up development microapartment layouts, others have been trying to bring the coliving model to existing buildings. In 2010, Brad Hargreaves co-founded General Assembly, a start-up that helps individual and corporate teams learn “digital” skills, including software development, user experience design, data analysis, and online marketing. As the business grew, Hargreaves found himself increasingly occupied with finding a place for his students to live.

Several trends have been coalescing to make it difficult for young professionals to find an affordable and convenient place to live. People are getting married later or not at all, reducing the average household size. More young people are moving into large cities in search of good jobs (even though migration, on net, was negative in many cities). On average, young urban professionals are also staying in the city for longer, delaying or avoiding buying a home and moving to the suburbs. This means that a growing swath of the population is renting.

The growing preference to rent rather than own is itself driven by a combination of record levels of student debt, as well as a robust but unstable employment market (as detailed in the Office section). Renting is also aligned with a broader change in consumer preferences toward push-button solutions that has emerged to fill every human need. Apps provide everything, from on-demand transportation and food delivery, through housekeeping and professional services, to dating and social interaction.

On the supply side, cities such as New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C., have zoning and policies that make it difficult to build units for single residents. Some policies encourage developers to build luxury units that are less regulated or to build units for various government programs in exchange for tax breaks or other concessions. Meanwhile, not enough units are being built for urban residents who can’t afford luxury but did not qualify for various government welfare programs. Other global cities such as London, Amsterdam, Berlin, Shanghai, and Tel Aviv also suffer from a similar shortage of rental apartments that are suitable for single residents.

In 2015, Hargreaves decided to develop a solution of his own through a new venture, Common Living. As a first step, Common took over an 84-year-old building in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. The four-story brick building was originally built to serve as the home of a single, wealthy family. Over the years, it was divided into several separate apartments for working-families who

probably moved to the area after World War II. Common converted it into a single building with 16 bedrooms to house a group of unrelated individuals. Hargreaves figured that using existing buildings would allow him to bring a product to market faster, iterate faster, and gather insights and validation that would enable him to later move on to larger, ground-up development projects.

Common furnished all the bedrooms and shared areas, provided basic supplies and cleaning services, helped match roommates, and developed a legal process less painful than a typical lease. True to Hargreaves’s digital roots, the company launched as a digital brand, with a website that allows potential residents to see Instagram-style photos of their future home and learn about life in the neighborhood. It is also planning to provide virtual 3D tours. It offers new residents the flexibility to commit to less than a year and to move freely between other projects in Common’s portfolio.

Common’s online distribution channel enabled it to attract residents to parts of Brooklyn that they did not originally intend to live in. At the time, Crown Heights was affordable to young professionals, but its reputation was that of a less safe and less cool destination, particularly when compared to neighborhoods such as East Village or Williamsburg which were top destinations for young professionals at the time. But most of all, most newcomers and many New York residents were not aware that Crown Heights existed. Common’s digital narrative, service package, and flexibility gave residents the confidence to give it a go.

Unlike Ollie’s, Common’s first buildings were not particularly dense. But the ability to draw residents to new areas enabled the company to make margin. Common did not price its rooms based on the neighborhood they were in. Instead, it priced them based on the budgets of its target customers. A resident who planned to spend $1800 a month on an empty bedroom in a traditional shared apartment in East Village could, instead, spend the same on a fully furnished and serviced room in a fully renovated Common property in a less desirable neighborhood.

For the customer, that meant a better experience and a lower overall cost when factoring in utilities, furniture, and various moving costs. For Common, that meant a rent per square foot that was about double compared to similar properties, and an NOI lift of 30%–40%. In a sense, incumbent landlords in popular neighborhoods provided Common’s early projects with a price umbrella, setting tenants’ expectations of how much should be spent on housing.

Common proceeded to open dozens of additional properties in seven other cities and expanded its model to include management deals and ground-up development projects. As of Q2 2019, Common’s website generates more than 15,000 direct leads from prospective tenants—much more than the company can accommodate in its existing projects. This is a remarkable fact in an industry where landlords normally rely on brokers to “move their inventory”.

The most interesting aspect of Common’s evolution is not the growth of its coliving brand—it is its ability to parlay its unique capabilities into other residential products and a different position in the real estate capital stack.

In March 2019, Common announced a joint venture with Tishman Speyer, one of the world’s largest real estate owners and developers. The new venture, dubbed Kin, will be America’s “first residential brand tailor-made for families living in and near cities”.ccci Kin will develop and operate multifamily projects that are purpose-built for families. The idea is to couple Tishman’s development and financing capabilities with Common’s technology, operations, branding, and community management expertise.

Kin projects will include larger units and amenities that focus on children, education, and the needs of parents, and will be located to ensure easy access to school and employment areas. Unlike Common’s coliving projects, Kin apartments will not be shared and buildings will be programmed with events and activities that are suitable to the target demographic, including swimming lessons, enrichment classes, and kid-friendly holiday parties. Kin’s mobile app enables residents to access shared resources such as toys, playrooms, and even last-minute babysitters or longer-term nannies.

Kin currently operates a section of Jackson Park, a larger project developed by Tishman Speyer in Queens, New York—about 300 feet from Ollie’s Alta project. Jackson Park includes 1871 apartments and 120,000 square feet of amenity spaces. New and existing residents can pay a monthly fee in order to access all Kin services or opt out and receive only basic property management services.

Kin was launched while we were writing the final pages of this book, so we did not have an opportunity to gauge its performance over time. However, the mere existence of this venture is a milestone in the evolution of coliving operators and of Common in particular. The company originally focused on smallscale fixer-upper projects in less desirable neighborhoods that catered to under-served, low-value customers.

Fig. 15.1 The trajectory of disruptive innovation in the multifamily sectorcccii

The company invested time and (venture) capital to develop tools and methodologies that are essential to the operation of residential projects in the twenty-first century. Common is using its brand, technology, and operational capabilities to gradually move upmarket and take on larger, ground-up development projects in more desirable neighborhoods (Fig. 15.1).

Other coliving operators have relied on diverse sources of capital from property investors to develop new projects. Starcity raised the $1.8 million in equity required for an adaptive reuse project in San Francisco’s Lower Haight on EquityMultiple.com, a crowdfunding platform.ccciii Medici Living, owner of the Quarters coliving brand, secured a $1.1 billion commitment from CORESTATE Capital Group to acquire and develop as many as 30 coliving projects in Europe.ccciv We already mentioned Ollie’s collaboration with developer Simon Barron above. But Common’s Kin partnership is the first to cross the chasm from coliving toward the mainstream of the multifamily market— catering to middle-class families who are comfortable committing to a 12-month lease and are more motivated by experience and convenience than price.

If Kin will prove to be a success, it would position Common as a legitimate competitor in the multifamily market, prompting more incumbents to launch brands of their own or to partner with emerging operators such as Common, Starcity, Ollie, and others.

Bundling multiple services and amenities into a single building is not a new idea, but it can benefit from a technology-powered revival and optimization. But ground-up development sites are relatively rare in dense urban areas, and those that are available are usually too small to fit a large building. Small buildings, in turn, cannot justify the costs of large amenity areas or any investment in proprietary technologies or services.

Venn, a Tel Aviv-based housing start-up, came up with a novel approach to provide small apartment buildings with rich amenities, services, and a sense of community. Instead of helping residents share an apartment or a building, Venn enables them to share a whole neighborhood. In Brooklyn, Berlin, and Tel Aviv, the company operates clusters of buildings that are located within walking distance from one another. The buildings include new or renovated furnished apartments. Aside from residential buildings, the company’s network includes communal areas and businesses that are spread across the neighborhood, from cultural centers to gyms, childcare facilities, restaurants, household tool “libraries”, dry cleaners, and more.

Venn ensures that each of its “hoods”, as it calls them, include a critical mass of services and communal spaces by providing seed capital to local business owners or by operating some spaces and services on its own. Venn members receive access to all the amenities in the hood, as well as to community events and activities and housekeeping services. Membership is open to any neighbor, including those who live in buildings that are not operated by Venn. Venn’s operating philosophy, captured in a book written by its founders, sees neighborhoods as central to people’s identity, convenience, and personal growth.

Unlike many coliving and coworking start-ups, Venn did not begin by spending venture capital on signing leases or acquiring buildings. Instead, the company relies on a capital stack that includes real estate private equity, real estate debt, corporate debt, and venture capital (Table 15.2). The private equity comes from investors who acquire (or sign long-term master leases for) properties that Venn can operate. The debt finances more typical business expenses such as capital expenditures for renovation and furniture. And the venture capital finances the development of Venn’s branded technology and services platform that powers its projects across the world.

This model enables Venn, its investors, and its lenders to transform less desirable neighborhoods and capture more of the increase in property value

Table 15.2 Venn’s capital stack

|

Type of capital |

Uses | |

|

Venture capital |

→ |

Technology R&D, brand, teams to select and service properties in the company’s management portfolio. |

|

Corporate debt |

→ |

Capital expenditures necessary to renovate and furnish properties in the company’s portfolio. |

|

Real estate debt |

→ |

Augment the equity when acquiring properties. |

|

Real estate equity |

→ |

Acquisition of properties for Venn to operate. |

created by its activities—not just the value of a single residential building, but the value of multiple residential and commercial buildings and multiple local businesses. It also enables Venn to act as a sponsor of sorts in real estate acquisitions made by its affiliates, allowing the Venn platform to benefit from its contribution to the value of assets owned by third-party investors.

Regardless of Venn’s specific product and target demographics, its capital stack is an example that many real estate companies may follow in the future. As residential (and commercial) assets become more reliant on branding, technology, and thicker operating layers, it makes sense for the real estate capital stack to evolve and enable separate investors to finance separate aspects of the business in a way that is commensurate with their risk appetites and mandates.

Venn is already in the process of “upgrading” parts of the Shapira neighborhood in Tel Aviv, Bushwick in Brooklyn, and Friedrichshain in Berlin. To existing residents, the company’s model may seem like a “gentrification machine”, a systematic way to increase property prices and make a neighborhood unaffordable to its original residents who are usually renters. To address this concern, Venn is exploring business models that would allow for more inclusive growth and benefit its neighbors, not just its customers and investors. One way to do so would be to enable small investors to become fractional owners of the buildings or neighborhoods they live in.

A similar challenge is being addressed by a collaboration between EFFEKT, an architecture firm, and Space10, a research and design lab backed by IKEA. The two companies developed a concept for an “urban village” that would provide reasonably priced housing units and access to a variety of shared services and amenities. The companies plan to allow residents to buy (financial) “shares” in the project as part of their monthly rental payment.cccv This way, locals will gradually build an ownership stake in the properties they use every day. The concept was presented in June 2019 at IKEA’s annual design conference. No details were published on when, where, and whether it would be actually built.

So far, we only discussed emerging models in the market for urban apartments. Before we conclude this section, it is worthwhile to look at how technology is reshaping the market for private residential houses in and around cities.

In February 2008, the New Yorker magazine interviewed Stephen Schwarzman, founder and then-CEO of the Blackstone Group. When asked about the five different residential properties he owns and uses, Schwartzman mused: “I love houses. I’m not sure why.”cccvi

The year 2008 was not great for houses. By the end of the year, the Case-Shiller Index tracked an 18% drop in the price of U.S. homes, the largest ever recorded.cccvii The delinquency rate for single-family residential mortgages jumped from less than 2% in 2006 to 6.59% in 2008 and shot to over 11.5% by the first quarter of 2010.cccviii Millions of homebuyers defaulted on their mortgages and lost their properties. Lenders, in turn, found themselves sitting on millions of distressed assets that they had to find new buyers for. This created an opportunity for Schwarzman’s Blackstone Group to own more houses than anyone on earth.

In 2012, Blackstone seeded a new company called Invitation Homes in order to “purchase distressed single-family homes and then refurbish, lease, and maintain them in neighborhoods across the country”.cccix Over the next five years, the company used proprietary software to identify and streamline the acquisition and renovation of about 48,000 homes.cccx Many of these properties were acquired in bulk, at the bottom of the market from lenders who had to liquidate foreclosed assets.

By 2017, Invitation Homes invested about $10 billion on acquiring and renovating houses. Most of the capital was provided by institutional investors that invested in Blackstone-managed funds. Such investors regularly allocate billions to investment in large office, retail, industrial, and multifamily properties but steer clear of smaller assets. Why?

The answer lies in transaction costs. Historically, it was too costly to identify and manage thousands of individual properties. It is much more efficient to deploy $500 billion on a single office building acquisition than to find, evaluate, and acquire 3000 separate houses for the same amount. Not to mention the coordination required to get all these houses renovated and resold.

But Blackstone was astute enough to realize that transaction costs have changed. Software and the various online tools made it possible to sift through millions of deals, manage thousands of concurrent bids and acquisitions, and to coordinate with local contractors and managers in dozens of cities. In other words, technology made it possible to turn single-family housing into an institutional asset class in which billions of dollars can be deployed each year.

The housing crisis provided Blackstone with an opportunity to turn this insight into an actual business. As the economy recovered, Invitation Homes was in a position to “flip” those houses back into the market and cash out. But that wasn’t the plan. Technology also made it possible to lease and manage a distributed portfolio with tens of thousands of houses. Instead of selling them, Invitation Homes rented them out. Its offering to tenants was more compelling than that of millions of smaller residential landlords. All the houses were professionally renovated and maintained and, as an option, leases were bundled with smart home systems such as digital locks, temperature controls, and energy management software. An online portal enabled residents to pay the rent and report maintenance issues.

Technology also played an indirect role in driving demand for rental housing. In particular, it contributed to a robust but volatile job market that makes it difficult for middle-class families to commit to a long-term mortgage. And it drove a shift in consumer preferences toward on-demand, turnkey offerings as well as a growing “preference” of access over “ownership”. These effects of technology are covered in more detail in the Retail and Office sections. Other economic factors also contributed to this shift. Overall, the number of renter-occupied housing units in the U.S. has grown by more than 20% or 7.5 million units from 2008 to 2018cccxi while the population has only grown by 7% or so.

In 2017, Invitation Homes’ portfolio was rolled into a real estate investment trust (REIT) and listed on the New York Stock Exchange. As of May 2019, it owned and operated over 80,000 homes. For comparison, each of the largest multifamily REITs, such as AvalonBay Communities and Equity Residential, owns and operates about 80,000 apartments across less than 300 individual buildings. This means that multifamily REITs only need to evaluate dozens or hundreds of potential acquisitions each year, compared to hundreds of thousands or million in the case of Invitation Homes. The amount of data that is aggregated and created during this process presents an opportunity for an even more radical business model.

Houses are typically owned by their occupiers or other small investors.

But the mortgages of these houses are concentrated on the balance sheets of lenders. The scale of the residential debt market is breathtaking. In the U.S. alone, about 600,000 residential mortgages are issued each month, representing a total over $1.5 trillion in new debt each year.cccxii

The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, commonly referred to as Freddie Mac, buys a big chunk of all new mortgages from smaller lenders and packages into mortgage-backed securities and other financial products that institutional investors can purchase. The reasons for this are complex and mired in controversy. For the purpose of our discussion, the salient point is that Freddie Mac needs to determine the value of the collateral for millions of mortgages—that is, houses—each year. Freddie Mac needs to do so without visiting the actual assets and without interacting directly with the borrowers.

Starting in the late 1990s, Freddie Mac developed a set of automated valuation models (AVMs) that generate an estimate of a property’s value within seconds. These models take into account data on comparable sales as well as so-called hedonic characteristics such as the number of bedrooms, number of bathrooms, and other features. According to information published on its website, Freddie Mac uses AVMs to verify the underwriting quality of mortgages it acquires, to evaluate overall credit risk in its existing portfolio and for other functions.cccxiii Lenders in other countries also use AVMs for similar purposes.cccxiv

Invitation Homes also relies on AVMs to determine the value of properties it acquires or already owns, but does so in tandem with more traditional appraisal methods, including physical inspections. Over the past two decades, AVMs made life easier (but not necessarily safer) for large lenders and large investors. For individual homebuyers and sellers, the acquisition process remained complex, time-consuming, and fraught with uncertainty and anxiety. Buying a home is often the most important financial decision in a person’s life. And unlike Blackstone or Freddie Mac, individual buyers put their own life savings at risk.

In 2014, a group of entrepreneurs set itself a mission to turn individual house purchases into a matter of “a few clicks online”.cccxv They founded a company called Opendoor, with the backing of some of Silicon Valley’s most prominent investors, including Khosla Ventures, PayPal co-founder Max Levchin, Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman, Quora CEO Adam D’Angelo, and Y Combinator’s Sam Altman.

True to its vision, Opendoor introduced a new way to sell and buy houses. Sellers can visit Opendoor.com, enter their home address, and fill in a detailed questionnaire. Within 24 hours, the seller receives a cash offer from Opendoor. The price is determined by an AVM that takes into account “thousands of features” and data points, according to the firm.cccxvi The valuation process is not always entirely automated. When the model indicates low confidence in its own estimate, an Opendoor employee can review and tweak the valuation before an offer is sent. If the seller accepts the offer, Opendoor sends a representative to inspect the property and verify the information provided. The seller has the option to close a deal and move out with a few days.

In addition to speed, sellers avoid the need to hold open houses for potential buyers, avoid dealing with contractors and handling repairs, and avoid the risk of a buyer failing to secure a mortgage after weeks of negotiations and discussions. Opendoor allows sellers to choose a preferred moving date—to align with their availability of their next home—and even offers a “late checkout” option for sellers who wish to get paid prior to moving out. For this pleasure, Opendoor charges sellers about 5%–8% of the sales price, which is comparable or slightly higher than the cost of a traditional transaction when taking into account typical broker fees, staging, last-minute concessions to buyers, and temporary accommodation due to uncertain moving dates.

Once a house has been acquired, Opendoor handles any renovations required in order to put it back on the market. For buyers, Opendoor offers the benefit of dealing with a professional seller and moving into a newly renovated home. As opposed to the coordination required with individual sellers, prospective buyers can visit Opendoor properties at all hours of the day, every day. And once a deal is done, Opendoor offers a 30-day satisfaction guarantee with the promise to buy the house back in case the buyer is unhappy.

Over the past few years, multiple other companies started adopting the Opendoor model. This includes home listings giants such as Zillow and Redfin, which have added instant offers to their sites. In the tech community, Opendoor and other companies that buy houses online have been dubbed “iBuyers”. The iBuyer model introduced unprecedented liquidity to the housing market, enabling people to buy and sell houses the same way they would sell a car or an appliance. Opendoor even offers a “trade in” program. In 2018, it partnered with Lennar, America’s largest homebuilder, to offer existing homeowners the opportunity to upgrade their current home to a new one.cccxvii

The iBuyer model blurs the boundaries between owners, agents, listings, and buyers. Its implications for brokers and listings sites are beyond the scope of this book. The iBuyer model also introduces new risks that are yet to be fully understood. The average holding period for a home on Opendoor’s balance sheet is around three months.cccxviii The company has raised over $1.5 billion in venture capital from investors such as Softbank, General Atlantic, and Lennar, and relies on a combination of equity and debt to finance its acquisitions.

As of March 2019, Opendoor is active in 23 U.S. cities and claims to handle close to 3000 transactions a month.cccxix The company and its model have yet to face a significant housing slowdown. We note that in 2008, AVMs did not save Freddie Mac from reaching the brink of financial collapse and requiring a $100 billion government bailout. On the other hand, higher liquidity has shown to decrease the volatility of other assets such as stocks and currencies—but its impact on real estate merits further research.

The Opendoor experiment is worth the risk. It is justified by the size of the opportunity. And unlike other speculative housing ventures, the company and its competitors make life better for individual buyers and sellers. As analyst Ben Thompson pointed out, technology is reshaping the job market and creating opportunities in different areas than where job seekers are located. By increasing the liquidity of the housing market, Opendoor and other iBuyers have the potential to make the overall job market more dynamic and make it easier for people to move toward better opportunities.cccxx For now, iBuyers only impact a tiny share of the housing market. The University of Colorado’s Mike DelPrete estimates that in 2018, Opendoor and its competitors were involved in only 0.2% U.S. housing transactions.cccxxi But they are growing fast and attracting significant amounts of capital.

Can the iBuyer model apply to commercial assets such as offices, retail projects, and multifamily buildings? Not just yet. iBuyers have access to plenty of relevant data. It’s easy to compare single-family homes and with millions of annual transactions. In contrast, there are only a few thousand commercial property transactions a year, and even these are spread across different countries and asset types. The world has millions of near-identical houses, but most office or retail projects are unique in their size, design, and features, not to mention additional factors such as mechanical systems or air rights.

The comparison method is generally less relevant in commercial valuations since commercial assets are valued primarily based on their expected cash flow. That cash flow, in turn, is a factor of dozens or hundreds of office, retail, and residential leases or operating agreements with hospitality operators. Commercial projects also have more complex debt and cash flow distribution structures that require deeper analysis and modeling. All these leases and financial arrangements reside across multiple documents, often only on paper.

That said, automated valuations can help commercial investors sift through hundreds of opportunities and decide which ones are worth further attention. Technologies such as machine vision and natural language processing make it easier to consolidate and analyze data from different documents and sources. This means that processes that previously required hundreds of man-hours can now be expedited. Also, technology makes it easier to aggregate data from additional sources.

A start-up called Skyline AI analyzes traditional and non-traditional data to identify attractive investment opportunities in real estate assets. Non-traditional data can include anything from social media posts to energy usage and traffic patterns. Skyline bills itself an “artificial intelligence asset manager for commercial real estate”. The company has raised over $25 million in venture capital from investors such as Sequoia Capital and JLL Spark. In 2018, it started working with large real estate investors such as DWS Group and Silverstein Properties to identify multifamily investment opportunities. It is too early to determine whether Skyline’s approach will yield superior results.

16

The technological and demographic changes of our age correspond with those of the late nineteenth century, fueling demand for housing solutions that are shared, flexible, serviced, and urban. Today’s plain apartment buildings were once considered radical, opposed by social critics, and avoided by most “proper” people. The notion of sharing a hallway, a laundry room, an elevator, or a roof with other families was seen as a recipe for moral decline. Perhaps it was then, but we now consider it normal. In turn, many of today’s radical design, ownership, and operating models will seem mundane to our children (if we have any).

Technology facilitated the emergence of new urban industries that attracted young people to the cities. These people found ways to live in buildings that were formally designed for other uses. At the low end, that meant using singlefamily buildings as tenements for dozens of unrelated individuals, sleeping in bunk beds. At the middle and upper end, it meant using hotels as homes. Gradually, the market caught up and consumer behavior was formalized in new apartment buildings.

But technological and demographic trends seldom continue indefinitely. They are embedded in a political and social context. And technology itself continues to evolve to different effects. Urban housing solutions that emerged organically were regulated out of existence or deserted by middle- and upperclass residents. The trains and industrial facilities that pushed cities inwards and upwards gave way to cars and trucks that enabled and encouraged sprawl.

Cars combined the flexibility of the horse carriage with the speed of the train, unlocking new areas where urban professionals could live and where travelers could stay. For hotels in particular, the abundance of potential

l ocations translated into a growing reliance on recognizable brands and efficient distribution channels. Hotel “landlords” evolved into three distinct businesses: property ownership, property management, and brand franchising. Technology demanded this evolution. Cars gave customers choice, mass media made it possible to build brands, and telephones and teletypes made it possible to centralize all booking and sales activity.

Hotel brands were able to consolidate thousands of properties under a single flag and a single distribution channel—holding leverage over property owners and travel agents. But online travel agents (OTAs) proved to be different than their predecessors. They were not simply another channel; they aggregated hundreds of thousands of properties and offered customers unprecedented number of options, as well as new tools to help them choose. OTAs put independent hotels on equal footing with branded ones. And their concentrated power gave them leverage over brands, forcing them to cede some pricing and inventory management.

But digital distribution channels did not simply change how hotels were sold. They changed what hotels are. Airbnb unlocked millions of rooms in new inventory by lowering the cost of finding, booking, and trusting them. Others used Airbnb as a channel to offer a more standardized lodging product, with a business model that flipped the real estate on its head: Sonder built an online brand first and then proceeded to standardize its actual physical product. Airbnb, meanwhile, used its own distribution power to affect how some projects are designed and developed. Soon, it might start developing (or manufacturing) housing or lodging units on its own.

The old definitions are losing their meaning. Hotel listing sites like OYO are becoming hotel franchises. Travel booking sites like Expedia are going into home-sharing. Home-sharing sites are adding independent hotels. Hotel franchises are acquiring or launching home-sharing businesses. Everyone is trying to spread the upfront costs of building unique technology products and brands across a larger number of properties and customers.

These dynamics from the lodging industry are making their way into the residential world. New operators are introducing a new level of service and flexibility, and designing products that cater to the needs of specific customers (and not everyone). Companies like Common Living and Ollie are building their own digital distribution channels and are building branded residential franchises. Their initial focus was on under-served, low-end customers, but they are gradually making their way upmarket. They do so with the backing of large venture capital and real estate investors.

Just like in the nineteenth century, it is becoming difficult to draw a line between housing and lodging. The same physical asset is used differently depending on the channel through which it is marketed: leased for a year through a traditional leasing agent, booked for a night on Airbnb, or offered for several months through a serviced operator like Sonder or Lyric. Many customers who can afford to own prefer the convenience and flexibility of renting and expect better service and more specialized solutions.

Technology also facilitates the aggregation of whole new asset types into rental platforms. Single-family houses are being consolidated into large portfolios, managed under a single brand, and financed by investors that previously acquired only larger commercial assets. Even the boundaries between renting and owning are being blurred by technology. iBuyers use data and venture capital to bring unprecedented liquidity to the housing market, enabling people to sell or buy a house within days. Meanwhile, companies such as Space10 and Venn are exploring models that would enable long-term renters to build an equity stake in the houses and community facilities they use every day.

Technology is changing residential and lodging units in many other ways that were not covered in this section. Connected devices make it possible to create new experiences and offer new services. They also raise new privacy concerns and liability risks which will be addressed in the final chapter of this book. Robotic furniture from companies such as Ori Systems and Bumblebee Spaces makes it possible to use the same spaces in completely different ways throughout the day. On-demand apps handle daily necessities from laundry, to food delivery, to storage. By doing so, these apps “transfer” activities that used to require space inside the home into other locations. On the other hand, the constant stream of packages and deliveries requires residential buildings to add new facilities and systems and, in some cases, whole service corridors and back-of-house facilities—just like hotels. Meanwhile, new construction materials and techniques promise to make houses and apartments more affordable, more sustainable, and more pleasant to live in.

Finally, as we consider how people live, technology’s bigger impact might be on where they live. Technology enables goods and people to move around faster, for much lower costs, and along new paths. It also disrupts employment patterns and work styles, concentrating certain jobs in a few areas while dispersing (or eliminating) others. In the next few decades, these developments are likely to cause a displacement of value on par with those caused by the train and the automobile. We looked at technology’s impact on employment in the Office section. In the next section about Logistics and Industrial properties, we explore the impact of new transportation systems.