Mark Twain had indeed come a long way from his first trip in 1866 to Hawaii. Back then he was a young, scrambling reporter for a California newspaper. As his life progressed, he developed a drive for financial success. He had gone through disastrous business endeavors, including the bankruptcy. By 1895 Twain was back with the American Publishing of Hartford traveling around the world to pay off the $100,000 debt, and had started “to write himself into affluence” (Wilson 7). His books were now more complicated and became valuable pieces of merchandise. As he aged, he seemed to ponder about his illusions of life.

Mark Twain had often attempted to look at life through a veil of illusions. In Following the Equator, he warned his readers: “Don’t part with your illusions. When they are gone, you may still exist, but you have ceased to live” (Bellamy 222). He would remark: “Ah, the dreams of our youth, how beautiful they are, and how perishable! … Oh, our lost Youth–God keep its memory green in our hearts! For age is upon us, with the indignity of its infirmities, and Death beckons!” (qtd. in Budd, Speeches 450). He also wrote in “Old Age” that one needs to climb to a summit in their old age and look back: Ah, then you see!” (qtd. in Budd 719). He commented further:

Down that far-reaching perspective you can make out each country and climate that you crossed … you can make out where Infancy merged into Boyhood; Boyhood into down-lipped Youth; Youth into indefinite Young-Manhood; indefinite Young Manhood into definite Manhood; definite Manhood with aggressive ambitions into sobered and heedful Husbandhood and Fatherhood; these into Old Age, white-headed, the temple empty, the idols broken, the worshippers in their graves, nothing left but You, a remnant, a tradition, belated fag-end of a foolish dream, a dream so ingeniously dreamed that it seemed real all the time… (qtd. in Budd 719)

The dream of the Sandwich Islands did call him back and sentiment took hold of him as his ship, the Warimoo, steamed to within sight of Diamond Head and Mark Twain encountered the vision of paradise he had longed all those years to see:

On the seventh day out we saw a dim vast bulk standing up out of the wastes of the Pacific and knew that spectral promontory was Diamond Head, a piece of this world which I had not seen before for 29 years. So we were nearing Honolulu, the capital city of the Sandwich Islands–those islands which to me were paradise; a paradise which I had been longing all those years to see again. Not any other thing in the world could have stirred me as the sight of that rock did… (Twain, Following the Equator 24)

Mildred Clemens would further quote Mr. Twain:

Many memories of my former visit to the island came up in my mind while we lay at anchor in front of Honolulu that night. And pictures–pictures–pictures–an enchanting procession of them … we lay in luminous blue water; shoreward the water was green–green and brilliant; at the shore itself it broke in a long white ruffle, and with no crash, no sound that we could hear. The town was buried under a mat of foliage that looked like a cushion of moss. The silky mountains were clothed in soft, rich splendors of melting color, and some of the cliffs were veiled in slanting mists. I recognized it all. It was just as I had seen it long before, with nothing of its beauty lost, nothing of its charm wanting … and it made one drunk with delight to look upon it. (qtd. in M. Clemens 11)

Mark Twain was scheduled to have lectured in Honolulu. In his notebook he commented on the five hundred booked lecture seats sold out for his advertised appearance. Mark Twain was a legendary writer and performer by 1895, and it was natural that the Hawaiian people were excited that he was coming to the islands. He had made no secret that he had to lecture around-the-world for the honor of discharging the burden of bankruptcy. Twain was eager to return to a land that had offered him the opportunities to make his name known to a wider audience, first as a reporter for his 1866 Hornet scoop, and then as a lecturer with his popular “Sandwich Islands” lectures.

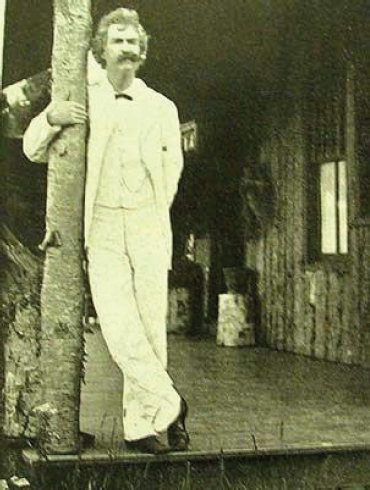

Twain and the Customary White Suit

Hawaii prepared for his return trip with much fanfare. Tickets sold fast at the Park Pavilion for the August 24 event (Zmijewski 22). Twain would have only a day in Honolulu due to the tight schedule of the cargo ship Warrimoo. Local newspapers informed the public:

The sale of seats for the Mark Twain lecture on Saturday night has exceeded all expectations, and the success of the affair is already assured. Manager Levey has secured the services of the Kawaihau Quintette Club which will render entirely new selections and songs between the remarks of the humorist … extra cars will be run on King and Beretania streets before and after the lecture. (Zmijewski 22)

The Independent said: “It is safe to say that every chair which Level can manage to squeeze into the hall will be occupied. It is the one chance in a lifetime to see and hear the greatest humorist of the century” (17 August 3). The Pacific Commercial Advertiser said: As a humorist, Mr. Clemens has no equal, and everyone who has read his Innocents Abroad or Tom Sawyer will enjoy his entertainment and be well repaid for the time and money spent” (21 August, 1).

One more publicity release about Twain came from The Hawaiian Star on the day the performance was to be held at Independence Park. The paper printed Twain’s own words of praise for the islands, his prose poem.

Twain’s visit, which had been advertised for August 24, had to be delayed for a week because the steamer Warrimoo had run aground in dense fog soon after leaving Victoria. On the evening of August 30 the Warrimoo arrived and anchored off Honolulu. Twain would record in his notebook:

Oahu … just as silky and velvety and lovely as ever. If I might, I would go ashore and never leave. The mountains right and left clothed in rich splendor of melting color, fused together. Some of the near cliffs veiled in slanting mists–beautiful blue water; inshore brilliant green water … Two sharks playing around laying for a Christian. (qtd. in Wilson 11)

Morning came and with it a tragedy, perhaps a tragedy too melodramatic to be realistic. There had been a plague of cholera in Honolulu, and no one was allowed to leave the ship. One might picture the sight of Mark Twain, standing alone on the deck of the Warrimoo, looking toward the Honolulu shore. Perhaps he wondered how the city of Honolulu had changed in twenty-nine years. Later, remembering this moment in Following the Equator, he wrote:

Many memories came up in my mind while we lay at anchor in front of Honolulu that night … disappointment of course. Cholera had broken out in the town, and we were not allowed to have any communication with the shore. Thus suddenly did my dream of twenty-nine years go to ruin.” (Twain, Following the Equator 31)

Mr. Clarence L. Crabbe remembered the moment well. He was wharf superintendent, and had gone out to the Warrimoo. He had immediately recognized Mark Twain, who was reclining on the steamer in a chair with his cap pulled down over his eyes, “looking dreamily up Nuuanu Valley back of ‘the white town of Honolulu’” (M. Clemens, “Twain in Paradise” 11). Mr. Crabbe addressed him with the question: “Would you like to go ashore, Mr. Clemens?” To this the reply was, “I would give a thousand dollars to go ashore and not have to return again” (qtd. in M. Clemens, Honolulu Star Bulletin 11). Twain said: “Pele’s curse had come true after all. She had bested me in the end. Those dreams of my younger days were gone forever” (qtd. in Davids 5).

The Warrimoo lay at anchor until midnight that long ago day, and then it bore Mark Twain away forever from the shores of a land he had so longed to return to, but would never physically approach again although he did visit the Hawaiian Islands through his treasured memories and by his writer’s pen.

Perhaps it was better this way. Perhaps it was circumstance. Mark Twain was no longer thirty and in reckless pursuit of his destiny. He was famous. He had suffered deep personal tragedies, including the death of his son, Langdon. He had lived in Europe five years and had gone through traumatic business financial losses (Baldanza viii-ix). And the Islands had changed too since their discovery by the civilized world. The Hawaiian Islands he remembered from twenty-nine years ago were an illusion. He mentions in Following the Equator that he talked with passengers whose home was Honolulu:

In my time Honolulu was a beautiful little town, made up of snow-white wooden cottages deliciously smothered in tropical vines and flowers and trees and shrubs; and its coral roads and streets were hard and smooth, and as white as the houses. The outside aspects of the place suggested the presence of a modest and comfortable prosperity–a general prosperity– perhaps one might strengthen the term and say universal. There were no fine houses, no fine furniture … but Mrs. Krout (a passenger on the boat and a current Honolulu resident) said Honolulu had grown wealthy since then, and of course wealth introduced changes; some of the old simplicities have disappeared … including the riding horse. In Honolulu a few years from now he will be only a tradition… (Twain, Equator 33-9)

Better that Mark Twain remember the illusion of his Hawaii as it was when he was young, a wise-cracking, wild spirit with tousled red hair and a mustache, when he was a cigar smoking wanderlust traveler going everywhere, talking to everyone, seeing everything he could see.

Mark Twain would further expound upon the topic in a source some critics consider to be his legendary lost Hawaiian journal:

I certainly must have been daft when I departed from Honolulu in 1866, never to return for 29 years. I probably should have stayed there forever. Literary success has been gratifying, but financial disaster has not. Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn, A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur’s Court and all my other efforts at yarn-spinning may have made me famous, but somehow my pile of debts has always remained higher than my stack of letters from well-wishers and admirers. The fact is, I did not know how well off I was, as a youngster of 30, to have been gallivanting around Honolulu and all those Sandwich Islands. (qtd. in Davids 4)

Many critics believe Mark Twain was one of America’s greatest writers, but nothing he would say about Hawaii would be remembered as much as his famous prose poem he wrote and delivered at Delmonico’s in New York on April 8, 1889, at a dinner honoring two touring American baseball teams that had stopped briefly in Honolulu. By that time, he was so identified with Hawaii that the master of ceremonies introduced him as a native of the Sandwich Islands. His famous Hawaiian prose poem had now been published in newspapers, periodicals and books all over the world. The poem had been put into verse and set to music, and even printed on a postcard. The October, 1908 issue of Paradise of the Pacific would say: “The (prose poem) tribute has been given the widest publicity for the invitation of Hawaii tourist travel hitherward, and no doubt has benefited the Hawaiian Islands in a way its author did not dream of” (McClellan 21: 10-1). The prose poem reads:

No alien land in all the world has any deep, strong charm for me but that one, no other land could so longingly and so beseechingly haunt me sleeping and waking, through half a lifetime, as that one has done. Other things leave me, but it abides; other things change, but it remains the same. For me its balmy airs are always blowing, its summer seas flashing in the sun, the pulsing of its surf-beat is in my ear; I can see its garlanded crags, its leaping cascades, its plumy palms drowsing by the shore, its remote summits floating like islands above the cloud rack; I can feel the spirit of its woodland solitudes. I can hear the plash of its brooks; in my nostrils still lives the breath of flowers that perished twenty years ago. (qtd. in Frear 217)

Some journeys with appointments of dreams took Mark Twain away from it all, to places no one knew; some took Mark Twain to where it seemed he had always been. But whether he returned to a new town or visited a new culture, travel to the Hawaiian Islands, for Mark Twain, forever changed the boundaries of the world he once knew. How strange that he could never fully return, and how strange that Hawaii would never leave him. Perhaps it was circumstance.