PREFACE

ESPRESSO AND ME

Some years back I realized that espresso cuisine was definitely established in America when Dave’s Coffee Shop in Oakland, California, situated across the street from two automobile dealers and next to a store selling floor coverings, put up a large sign indicating that it too, along with every other place in town, finally served “espresso” (spelled correctly, with an “s”), thus assuring that the nearby automobile salesmen and high school students, not to mention motorists on the long, dry run between caffès in downtown Oakland and Berkeley, need no longer be deprived of their cappuccino or caffè latte.

This is a book that attempts to demystify espresso in all of its varied incarnations: from the purist’s short pull to the shopping mall cuisine of chocolate-almond caffè lattes. Espresso cuisine is mysterious not only because it is produced by large, complex machines that make locomotivelike noises, but also because it is a relatively new alternative coffee tradition to the American cuisine of medium-roasted, light-bodied filter coffee. And because it is a different tradition, it brings with it other culinary procedures, other institutions, other rituals.

In the following pages I’ve tried to respond to most of the questions that might be asked about espresso: questions about its technical aspects, its history, its mythology, its culture, and above all, how to do whatever you want to do with it at home. I’ve attempted to give clear and complete advice about all aspects of producing good home espresso cuisine, while adding enough espresso history, fact, and myth to bring the procedures to life.

The Espresso Generation

My own involvement with espresso, at least in what might be called a professional sense, goes back to the time in my life when I nursed a cranky old Cimbali espresso machine in a caffè I co-owned and managed in Berkeley, California. Subsequently I sold the caffè and wrote a book on coffee, which is now in its fifth edition: Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing, and Enjoying. But espresso was not an afterthought in my personal coffee history. In fact, it started my coffee history. Since my experience is in many ways typical of my generation of coffee drinkers, it might be worth pursuing briefly.

Like many Americans who came of age in the early 1960s, I did not grow up drinking coffee. The only pressing choice I faced was whether to drink Pepsi or Coca-Cola. Coffee was sourish brown stuff drunk for unknown reasons by people over thirty, presumably while they occupied themselves with other peculiar middle-aged activities, like watching Ed Sullivan, listening to Frank Sinatra, and petting their cocker spaniels.

“Do You Like Coffee?”

The first inkling I had that there might be something worthwhile to the beverage was during my first college-student trip to Europe. While hitchhiking from France to Italy, I was picked up by a ruddy-faced Italian doctor. When we reached the Italian side of the border, he turned, squinted at me, drew himself up, and intoned grandly: “Do you like coffee?” The well-traveled reader will understand the length and sonorous authority of the vowels sounding in that question.

I responded that I wasn’t sure. Whereupon the doctor literally skidded to a stop in front of the next espresso bar (actually the first espresso bar, since we had just entered Italy), strode up to the counter, ordered two espressos, dumped several spoonfuls of sugar in his, muddled them, and drank the results, all in about the time that it took me to follow him in from the car.

I didn’t much care for that first dark little cup, but somewhere between Genoa and Florence I learned, like most Americans do, to order a cappuccino, and from there progressed and regressed through the rest of the carefully modulated drinks of the Italian espresso cuisine, from milky latte macchiato to the corto espresso, barely enough rich, heavy, creamy espresso to cover the bottom of a demitasse. Along the way I learned to stand properly with one elbow on the bar, stare at the passing Fiats while downing my espresso drink in several swallows, then replace the cup on the saucer with the proper authoritative clack. Above all I learned to love the peculiar bittersweet richness of espresso drinks, which rings on one’s taste-buds like a delicious dark bellclap, a sort of musical accompaniment to the lingering resonance of the caffeine.

On my return to the United States I discovered the Italian-American caffè, that more leisurely, spacious throwback to an Italy before the advent of the espresso bar, and began to drink my cappuccinos in places like the Caffè Reggio in Manhattan, the Caffè Mediterraneum in Berkeley, and the Caffè Trieste in San Francisco. Caffès became my true home. Because most of them were across the street from a bookstore, I had everything I needed in life clustered around my temporarily rented marbletop table: books, newspapers, espresso coffee, sympathetic friends, plus an occasional sandwich. I recall spending long, fruitless hours in towns with neither Italians nor caffès, driving around looking for a proper cappuccino and a proper place to drink it. When I taught at the University of Hawaii for a year, I ended up learning not only to make my own cappuccino but roast my own coffee as well, since in those years there was not a single dark-roasted coffee bean on the entire island of Oahu, aside from the ones I roasted myself in a frying pan in my tin-roofed bungalow in Kaneohe.

Given that history, it perhaps was inevitable that I would be drawn to opening my own caffè, which I eventually did, and writing, first a book about coffee generally, and then a book on espresso in particular.

Espresso Thanks

In the course of that writing I have run up an enormous collective debt to those involved in the art and business of coffee and espresso.

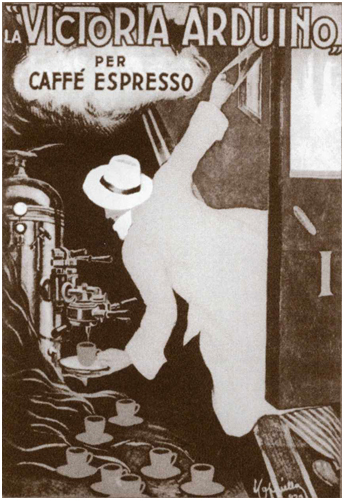

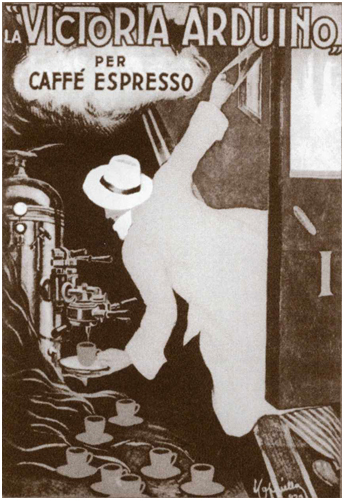

My thanks first to those individuals and businesses, particularly the Victoria Arduino company, the publishers of William Ukers’ All About Coffee, and BE-MA Editrice, publishers of Ambrogio Fumagalli’s Macchine da Caffè, or permitting me to make use of illustrations from their publications.

When I turn from businesses to individuals the list of those to whom I am indebted grows much longer. In fact, impossibly long. All I can do is name a few individuals whose input was particularly crucial in the making of the two editions of this book.

I would like to particularly thank Bob Barker, who read through the entire typescript of the first edition and made many valuable suggestions; collector Ambrogio Fumagalli of Milan; Christopher and John Cara of Thomas Cara, Ltd.; Don Holly and Ted Lingle of the Specialty Coffee Association of America; Sherri Miller of Miller & Associates; Kevin Knox of Allegro Coffee; the coffee cupper and pundit George Howell; Bruce Milletto of Bellissimo Coffee Education Group; Jim Reynolds of Peet’s Coffee & Tea; Don Schoenholt of Gillies Coffee; Lindsey Bolger of Batdorf & Bronson; Carl Staub of Agtron; and I had better stop there or the publisher will be forced to add another signature to the book.

To those individuals I would add the numerous others who assisted me in the research for the several editions of Coffee: A Guide to Buying, Brewing & Enjoying and for Home Coffee Roasting: Romance & Revival.

I consulted several useful books during the course of assembling this one, in particular Ambrogio Fumagalli’s Macchine da Caffè; Ian Bersten’s Coffee Floats, Tea Sinks; Edward and Joan Bramah’s Coffee Makers, 300 Years of Art & Design; Francesco and Riccardo Illy’s Coffee to Espresso; the Italian version of Felipe Ferre’s Il Caffè; Ralph Hattox’s Coffee and Coffeehouses, The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East; the Italian Istituto Internazionale Assaggiatori Caffè’s Espresso Tasting; Andrea Illy and R. Viani’s Espresso Coffee: The Chemistry of Quality; and Mariarosa Schiaffino’s Le Ore del Caffè and Cioccolato & Cioccolatini. Finally, the works of Michael Sivitz and William Ukers continue to be invaluable.

The notes and records of the ongoing saga of coffee and coffee culture recorded in Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, Fresh Cup, and other coffee industry magazines were constantly useful, as were the publications of the Specialty Coffee Association of America.

Finally, I am delighted to have an opportunity to thank my original editor, Annette Gooch, and my current editor, Keith Kahla; my agents, Richard Derus and Claudia Menza, and illustrator Michael Surles.

A concluding word of gratitude to those many professionals and enthusiasts in the United States, Italy, and Latin America whose insight has enriched and enlivened my view of espresso, even though I may have lost their cards or misplaced my scribbles on the backs of product literature. The achievements of this book are owing in great part to those who assisted me; the mistakes are mine alone.