What Is… GRADE THIRTEEN?

After I came back to Sudbury from military college, I had no money. For a couple of months I stayed in a tiny room in the annex of the Nickel Range Hotel, where Dad worked. It was just across the hall from another tiny room where he would change into his work clothes each day.

Then I went to stay with an uncle and aunt—my mom’s brother and his wife. Most of their kids had moved out, and they had an empty room. It was barely big enough to fit a bed and a desk. There wasn’t even enough room for my tape recorder, which I had to keep in the kitchen. My parents knew how much I loved listening to the radio, and they had bought me this tape recorder to tape music and programs. It was a huge machine—not your five-dollar cheapo. Taping music off the radio was always frustrating because so many of the announcers would talk over the orchestral vamp leading into the lyrics. If Frankie Avalon didn’t come into the song for twelve seconds, the announcer would talk that entire time. I hated that.

“Shut up!” I’d yell at the radio. “I want the whole song!”

Of course a few years later I would end up doing the same thing when I worked as a disc jockey for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC).

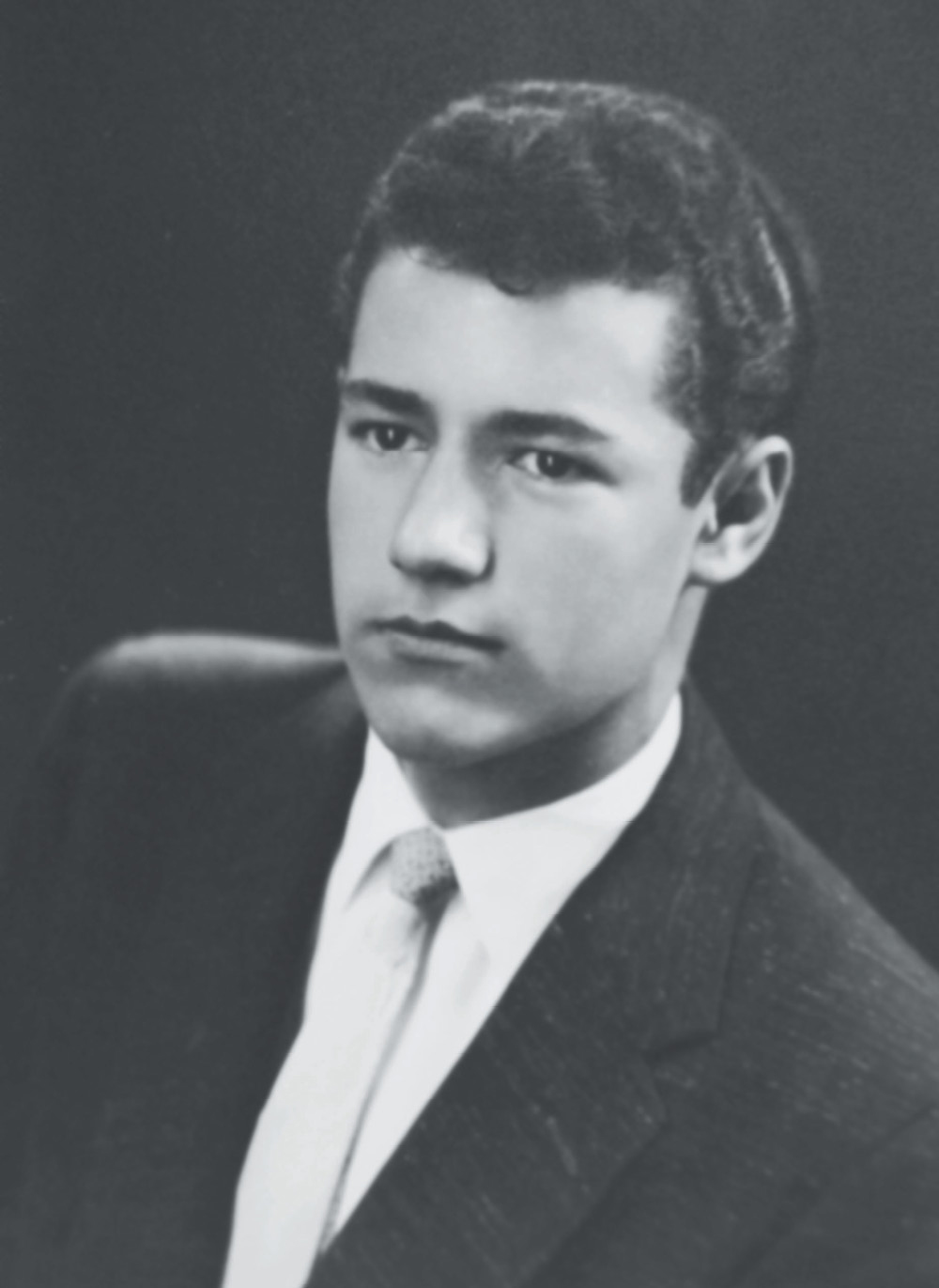

I always liked wearing suits, even before my career as a television host.

My uncle Ben would laugh at how upset I’d get. I could always make him laugh. While I was living with him and my aunt, he had thyroid surgery, and when I went to see him in the hospital he said, “Sonny, don’t you dare make me laugh or I’ll kill you!” It hurt too much for him to laugh.

Again, I didn’t have money to go to college, so I went back to Sudbury High for one more year. Ontario had what they called “matriculation year.” It was grade thirteen, or the equivalent of first-year university. My favorite subject was geography. I also liked geometry. Anything with a g. Geography, geometry… and girls.

The University of Ottawa boarding school had been all boys. Back in Sudbury, having narrowly escaped getting my hair buzzed off by the military, I started back up with my new girlfriend, Eleanor. I took her to the Sudbury High prom. Unfortunately, right before the dance she moved with her parents to North Bay, Ontario, which was about ninety miles away from Sudbury. Using Dad’s Ford, I had to drive ninety miles to go get her and ninety miles back. I had to leave Sudbury at two in the afternoon to pick her up. Luckily, she had arranged for another ride home. With Eleanor living so far away, our relationship soon fizzled.

I was very shy with girls. I was not forward at all. You would have to throw me into a girl’s arms and she would have to accept me willingly for anything to happen. I was not about to make the first move. But after Eleanor, I did fall in love with another girl. I took her to the movies; we held hands, but it wasn’t until after two features, three cartoons, and a newsreel that I finally got the nerve to kiss her.

After returning to Sudbury, I started hanging around again with Maurice Rouleau, my friend who swore a lot and whose dad owned the Nickel Range Hotel. He was also in grade thirteen at Sudbury High. The last week of school he got me in big trouble. It was our final gym class, and all the guys were excited. They thought they’d be funny, and so they grabbed some newspapers and magazines that were lying around in the locker room, got them soaking wet, mashed them up into balls, and threw them against the ceiling, where a lot of them stuck.

The gym teacher told the vice principal, Mr. Costigan, about this. So just before we were to leave class that day, Mr. Costigan came in and said, “I heard what you guys did this morning in the shower rooms. Those of you who were responsible stay here. We’re gonna go clean up your mess. And the rest of you can leave.” Well, I hadn’t been involved, and so I started to leave.

“Hey, Trebek,” Maurice called out, “you were there too.”

I responded in French with a mild obscenity. It did not occur to me that Mr. Costigan spoke French fluently. He came charging over three rows of benches, grabbed me by the armpits, lifted me up, and pushed me so hard against the blackboard that dust was coming out of all the cracks. Even though I was innocent, I wound up going with the other guys to clean up the mess.

As we were walking to the locker room, I said to Maurice, “You know I wasn’t there. Why the hell did you tell him that?”

“I was just fucking with you,” he said.

At graduation, my homeroom teacher, Kenny Gardner, took me aside. Kenny had once told students in another class, “There’s a kid in my homeroom, sits at the back of the class, doesn’t say a word. But in discussions, if the students are ever stumped and can’t come up with the answer to a question I’m asking, I’ll point to him and he gives me the correct response. He’s just a good student. Well-behaved.” That had gotten back to me, and it meant a lot, because I was mostly known for joking around in class, though never in a disruptive way. Years later, when I started hosting game shows, those words would take on added significance—seem prophetic even. Yet something Kenny told me that day at graduation would have an even greater impact on me.

He said, “Alex, you’ve had a good year. Do me a favor. Never lose your love of life.”

I was just torn apart by that line. Because somebody had finally recognized what I thought I was about.