What Is… THE TEN-THOUSAND-HOUR RULE?

My career during those early years in Los Angeles was a bit erratic and unusual. I was being offered hosting jobs for all kinds of shows. After just one year, The Wizard of Odds was canceled. It was canceled on a Friday and replaced on Monday by High Rollers, also hosted by me. That doesn’t happen very often. High Rollers was an easier game to host than The Wizard of Odds had been.

The Wizard of Odds required a lot of mathematical skills. Because of the Compliance and Practices Department, if I said, “There is one chance in 6.27 that this will happen,” and it was actually one in 6.28, they would come back and correct me.

I remember one show we got to the bonus round, where there were ten items each associated with a number. For instance, if I said “the Stooges,” that number was three. If I said “number of weeks in a year,” that number was fifty-two. It was the job of the contestant to combine four of those items and keep the total below a certain number. And if they did that, they won a car. In this particular bonus round, the contestant just missed coming in below the number.

“That’s too bad,” I said. “If you had chosen this other item…” Then I took another look at the numbers. “Wait a minute, the math doesn’t work. We screwed up. We made a mistake. You shouldn’t be punished for our mistake. So I’m going to give you the car anyway.”

The audience went crazy. After the show, I was walking to my dressing room, feeling good about myself for my wisdom and fairness. Burt Sugarman saw me and stopped me.

“Alex,” he said, “next time when you notice we’ve screwed up, we’ll just stop tape and rectify it. Don’t give the car away.”

At High Rollers there was a lot less pressure on me. It was just rolling dice. High Rollers lasted two years. While I was doing that, I was also hosting The $128,000 Question, which filmed in Toronto. So I had to fly back and forth to tape both shows. Then High Rollers was off for half a year.

During that time, I hosted Battlestars. I’ve always referred to that show as “the son of Hollywood Squares.” Hollywood Squares had nine celebrities. Battlestars had a smaller budget, so we could only afford six. Hollywood Squares had squares. Battlestars had triangles. The performer who came out of Battlestars and enjoyed the greatest success later on was Jerry Seinfeld. My favorite memory of that show was from another of our celebrity panelists, Tom Poston. Tom was a veteran film and TV actor who at that time was best known for his work on the sitcom Mork & Mindy. I was interviewing one of the contestants, a young lady who had just relocated to Los Angeles.

“Why did you come to California?” I asked.

“I came to find a husband,” she said.

Without missing a beat, Tom shouted out, “Whose husband did you come to find?”

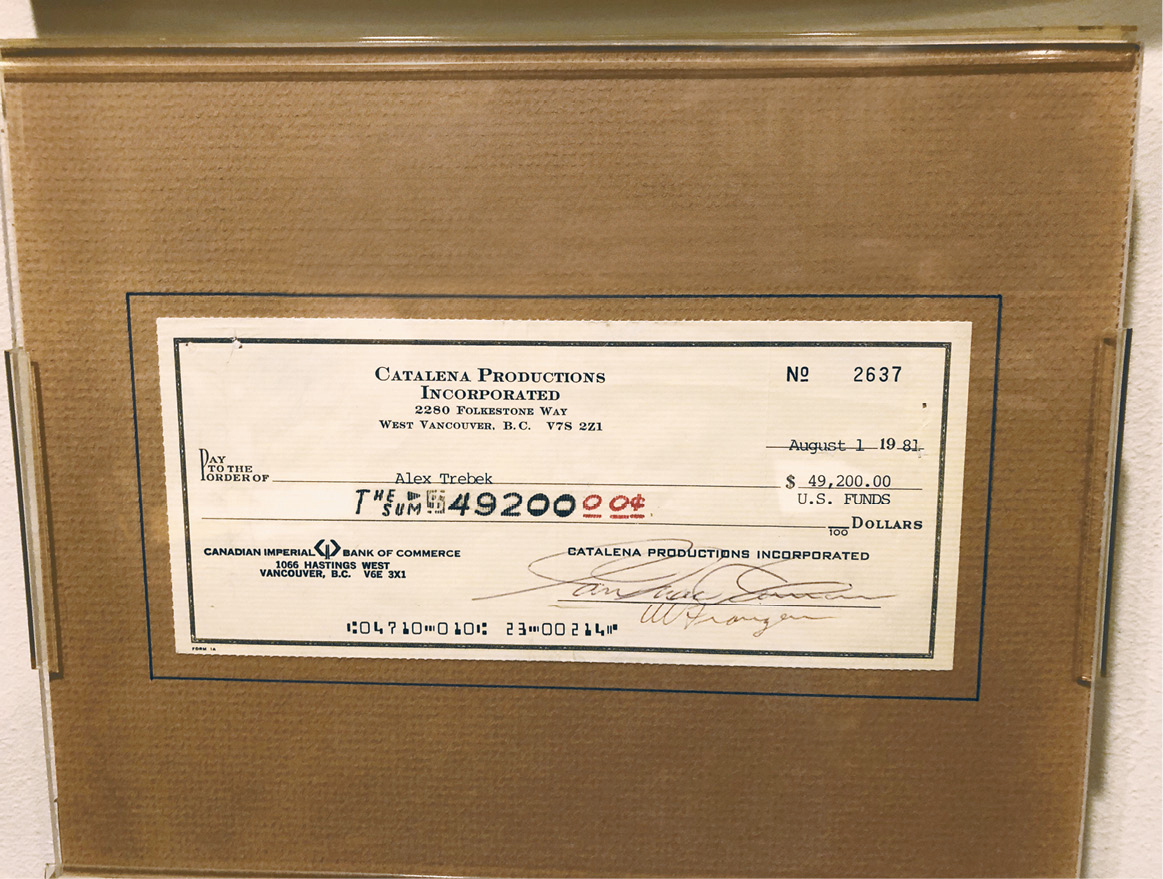

Battlestars didn’t last more than six months. I was then offered a job to host a game show called Pitfall, to be taped in Vancouver. This was during a difficult time in my life. My father was sick with cancer, and Elaine and I had just divorced. I needed the money for my new house. The job was supposed to pay me $49,000, which was a nice amount of dough back then. The one caveat was that I had to be a member of the Canadian union, otherwise they couldn’t hire me. No problem. I’d long been a member of the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists. So I signed the contract. Then I got up there, and the union said I couldn’t work on the show because the production company was not a signatory to the union agreement. There was a big dispute. The head of the show said that if I didn’t perform, they were going to sue me for breach of contract. And the union said if I did perform, I’d be in big trouble with them.

Finally, they got it all resolved. We did thirteen weeks of the show, and they paid me. Then we did another thirteen weeks, but this time the check didn’t clear. I went to the union and asked them to help. They said there was nothing they could do. That really ticked me off. I had stood up for them during the dispute with the production company, and now they weren’t willing to stand up for me. Through other channels, I discovered that I was one of dozens of people the show hadn’t paid, such as the set carpenters and other craftspeople.

I framed the check and hung it on the wall behind my desk where I’m writing this. It was the only time in my life I ever got stiffed on a payment. Whenever I think of the guy who did it, I recall Mark Twain’s famous line: “If ever I should hear of his sudden demise I will forgo all other forms of entertainment in order to attend his funeral.”

My memento from Pitfall.

I then hosted a show called Double Dare, which gave me my first opportunity to work with the legendary producer Mark Goodson. From Mark, I learned it doesn’t matter who comes up with a good idea. When I worked at the CBC, I would make suggestions to producers, and they weren’t always well-received. There was one producer-director who was a real jerk. I had been hosting this sports program for a couple of years. It was a show that filled time after football games on Sundays. We never knew how long the show would be. It depended on what time the game ended. If the game ended at 3:20 and we were supposed to be off the air at four, then we had forty minutes to fill. If the game ended at 3:50, then we had only ten minutes to fill. To deal with this, we set up a rack of sports highlight reels of various lengths, and while I ad-libbed an intro, a technician would cue up the reel whose timing most closely worked with our requirements. Well, this new producer-director came in and put all the different-length film clips on one big reel. So if we needed to fill only a couple minutes it wouldn’t work.

“I don’t think that’s a good idea,” I started to tell him. He cut me off.

“Are you the producer-director of this show?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

“What’s your job?” he asked.

“I’m the host,” I said.

“Then I’ll handle it,” he said.

And of course the arrogant SOB screwed it up.

Then I met Mark Goodson. When we first started working on Double Dare, I made a suggestion to him.

“That’s a good idea,” he said. Wow, I thought, Los Angeles is a different world than Canada.

Whatever my good idea was, it wasn’t good enough to keep Double Dare on the air. That show lasted twenty-six weeks at most. Then High Rollers came back for two and a half years.

In the midst of all this, I went back to Canada once more to film a show called Stars on Ice for the private network CTV. I was not a figure skater, but I had played hockey. They put me in skates, and I’d get out there every week with the entertainers. They had set up this large skating rink in one of the stages. The producer, Mike Steele, had directed shows in the United States, and he understood the concept of show business in a way that most Canadian TV executives did not. CTV’s lighter schedule put a great deal of pressure on the CBC to loosen up a bit and change its way of doing things. He wanted viewers to see TV not just as a government entity providing educational programming and prestigious dramas, but also shows that could make people laugh. Sure, the CBC had broadcast some great comedians such as Wayne and Shuster, who I grew up listening to on the radio and whose early television specials I loved. But for the most part, the CBC was more serious and straitlaced until CTV came along with programs like Stars on Ice.

In case you’ve lost count by now, that’s seven jobs in ten years. I never felt frustrated by the lack of continuity during those years. That’s just the business. For all the shows that are hits, there are dozens more that aren’t. I was just happy to have a job. There’s a lot to be said for being gainfully employed in the entertainment industry.

The producer Bob Noah, who I worked with on High Rollers, once said to me, “Alex, never turn down a job. You never know if another offer is going to come along.”

For a long time, as long as I was able to, I did not turn down jobs.

And I never doubted my talent either. I never took it personally when a show got canceled. I knew I was good. Because I had experience. I had spent more than a decade at the CBC. The author Malcolm Gladwell—also Canadian, I might add—has famously written about the “ten-thousand-hour rule.” He said that in order to master a craft, you have to spend at least ten thousand hours doing it. That’s what my time at the CBC was. Hosting every kind of program imaginable—it was a perfect apprenticeship.

Recently, I saw a pilot for one of those early game shows, and I said, “Damn, I was good.” I don’t always view myself the same way now. I don’t always come away saying, “Oh, you did a good job.” But I look at the nuances I brought to that pilot, and I say, “Man, that was fast. That was sharp. You were on your game. You were good.”

That was no fluke. I had put in my ten thousand hours. And I continued to improve and gain experience with those early game shows. So when I got invited to host yet another show, this one called Jeopardy!, I was ready.