Chapter 4

Digging into Accounting Basics

In This Chapter

Understanding accounting methods

Understanding accounting methods

Following debits and credits

Following debits and credits

Differentiating between assets and liabilities

Differentiating between assets and liabilities

Ah, the language of financial accounting – debits, credits, double-entry accounting! Just reading the words makes your heart beat faster, doesn’t it? The language and practices of accountants can get the best of anyone, but there’s a method to the madness, and working out that method is a crucial first step to understanding financial reports. In this chapter, we help you understand the logic behind the baffling and unique world of financial accounting. And you won’t even need a pocket calculator!

Making Sense of the Accounting Method

Officially, there are two types of accounting methods, which dictate how the company’s transactions are recorded in the company’s financial books: cash-basis accounting and accrual accounting. The key difference between the two types is how the company records cash coming into and going out of the business. Within that simple difference lies a lot of room for error – or manipulation. In fact, many of the major corporations involved in financial scandals have got into trouble because they played games with the nuts and bolts of their accounting method. We talk more about those games in Chapter 22.

Cash-basis accounting

In cash-basis accounting, companies record expenses in financial accounts when the cash is actually laid out, and they book revenue when they actually hold the cash in their hot little hands or, more likely, in a bank account. For example, if a painter completed a project on 30 December 2007, but doesn’t get paid for it until the owner inspects it on 10 January 2008, the painter reports those cash earnings in the accounts for the year ended 31 December 2008 – not 2007, even though that’s the year the painter did the work. In cash-basis accounting, cash earnings include cash, cheques, credit-card receipts, or any other form of revenue from customers.

In the past, smaller businesses, such as sole traders, might have used cash-basis accounting because the system is easier for them to use on their own, meaning they don’t have to hire accounting staff. However, HMRC make it clear that they expect all accounts – be they for sole traders, partnerships, or companies – to be prepared in accordance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), and that means accrual accounting.

If you’re a sole trader, partnership, or company, don’t even think about using cash-basis accounting. You must use accrual accounting (see the next section).

Accrual accounting

A company using accrual accounting records revenue when goods are delivered or work is performed, not when it receives the cash. That is, the company records revenue when it earns it, even if the customer hasn’t paid yet. For example, a carpentry contractor who uses accrual accounting records the revenue earned during the job, even if the customer hasn’t paid the final bill yet.

A recent and very controversial change to UK GAAP dictates that the carpenter would need to accrue revenue if the job was part completed at the financial year-end. For example, suppose a carpenter has a financial year-end of 31 December 2007 but was only part way through a contract to build an expensive bookcase. Assuming that the quotation for the job was £2,000 (excluding materials which were to be supplied by the customer), and that only 75 per cent of the work is completed at the end of December, then the accounts must show a revenue of £1,500 for the year ended 31 December 2007, even if no payment is actually received in the 2007 calendar year. This change in UK GAAP brought UK standards into line with the International Accounting Standard IAS 18 which is the standard relevant to listed companies.

Expenses are handled the same way as revenue. The company records any expenses when they’re incurred, even if it hasn’t paid for the supplies yet. For example, when a carpenter buys timber for a job it is probably paid for on account and no cash is laid until a month or so later when the bill arrives.

All companies must use accrual accounting according to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). If you’re reading a company’s financial reports, what you see is based on accrual accounting.

Why method matters

The accounting method a business uses can have a major impact on the total revenue the business reports as well as on the expenses that it subtracts from the revenue to get the bottom line. Here’s how:

Cash-basis accounting: Expenses and revenues aren’t carefully matched on a month-to-month basis. Expenses aren’t recognised until the money is actually paid out, even if the expenses are incurred in previous months, and revenues earned in previous months aren’t recognised until the cash is actually received. However, cash-basis accounting excels in tracking the actual cash available.

Cash-basis accounting: Expenses and revenues aren’t carefully matched on a month-to-month basis. Expenses aren’t recognised until the money is actually paid out, even if the expenses are incurred in previous months, and revenues earned in previous months aren’t recognised until the cash is actually received. However, cash-basis accounting excels in tracking the actual cash available.

Accrual accounting: Expenses and revenue are matched, providing a company with a better idea of how much it’s spending to operate each month and how much profit it’s making. Expenses are recorded (or accrued) in the month incurred, even if the cash isn’t paid out until the next month. Revenues are recorded in the month the project is performed or the product is shipped, even if the company hasn’t yet received the cash from the customer.

Accrual accounting: Expenses and revenue are matched, providing a company with a better idea of how much it’s spending to operate each month and how much profit it’s making. Expenses are recorded (or accrued) in the month incurred, even if the cash isn’t paid out until the next month. Revenues are recorded in the month the project is performed or the product is shipped, even if the company hasn’t yet received the cash from the customer.

The way a company records payment of payroll taxes, for example, differs with these two methods. In accrual accounting, each month a company sets aside the amount it expects to pay toward its monthly tax bills for employee taxes using an accrual (paper transaction in which no money changes hands, which is called an accrual). The entry goes into a tax liability account (an account for tracking tax payments that have been made or must still be made). If the company incurs £1,000 of tax liabilities in March, that amount is entered in the tax liability account even if it hasn’t yet paid out the cash. That way, the expense is matched to the month it’s incurred.

In cash accounting, the company doesn’t record the liability until it actually pays the government the cash. Although the company incurs tax expenses each month, the company will always be a month behind.

To see how these two methods can result in totally different financial statements, imagine that a carpenter contracts a job with a total cost to the customer of £2,000. The carpenter’s expected expenses for the supplies, labour, and other necessities are £1,200, so the expected profit is £800. The work starts on 23 December 2007 and is completed on 31 December 2007. No payment is received until 3 January 2008. The contractor takes no cash upfront and instead agrees to be paid in full at completion.

Using the cash-basis accounting method, because no cash changes hands, the carpenter doesn’t have to report any revenues from this transaction in 2007. But if cash is paid out for expenses in 2007 the bottom line is £1,200 less with no revenue to offset it. The result is that the net profit (the amount of money the company earned, minus its expenses) for the business in 2007 is lower. This scenario is not necessarily a bad thing if the carpenter is trying to reduce the tax hit for 2007 – which is, of course, why Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) outlawed it!

If the same carpenter uses accrual accounting, the bottom line is different. In this case, the carpenter books the expenses when they’re actually incurred. The income for the complete job is recorded on 31 December 2007, even though no cash payment is received until 2008. As a result the net income is increased by this job. Chapter 7 covers the ins and outs of reporting income on the income statement.

Understanding Debits and Credits

You probably think of the word ‘debit’ as a reduction in your cash. Most non-accountants see debits only when they’re taken out of their bank account. Credits probably have a more positive connotation in your mind. You see them most frequently when you’ve returned an item and your account is credited.

Forget everything you think you know about debits and credits! You’re going to have to erase these assumptions from your mind in order to understand double-entry bookkeeping, which is the basis of most accounting done in the business world.

The reason that people so often get confused about debits and credits is that their only experience of debits and credits is on their bank statement. The point about the bank statement is that it has been prepared from the bank’s point of view – and they are looking at the transaction from the opposite side to you.

Double-entry bookkeeping

When you buy something, you do two things: You get something new (say, a chair), and you have to give up something to get it (most likely, cash or you take a loan). Companies that use double-entry bookkeeping show both sides of every transaction in their books, and those sides must be equal.

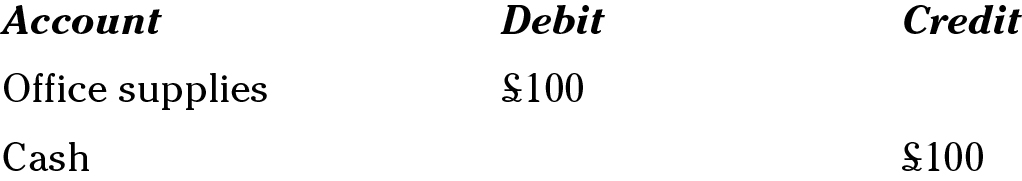

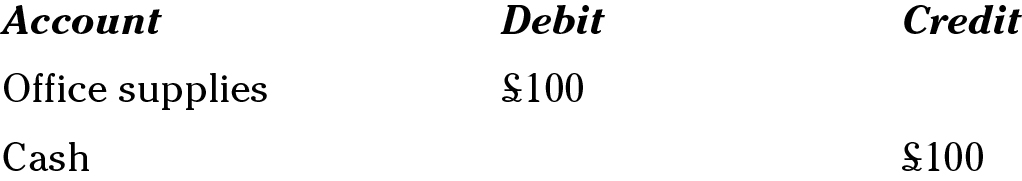

For example, if a company buys office supplies with cash, the value of the Office Supplies account increases, while the value of the Cash account decreases. If a company purchases £100 in office supplies, here’s how it records the transaction on its books:

In this case, the transaction increases the value of the Office Supplies account and decreases the value of the Cash account. Both accounts are asset accounts, which means both accounts represent things the company owns that are shown on the balance sheet. (The balance sheet is the financial statement that gives you a snapshot of the assets, liabilities, and shareholders’ equity as at a particular date. We cover balance sheets in greater detail in Chapter 6.)

Most businesses use double-entry bookkeeping. In the past, double-entry involved the business in writing the same figure twice into the accounting records – hence double-entry was a way of checking that the entries had been made accurately. These days the balance is enforced by a computer package – that is, the value is only entered once and the computer expects the operator to input the two accounts which are to be debited and credited. This may seem to be a good thing because the books will always balance but, in fact, the accuracy check of the entry is lost in computerised systems.

The assets are balanced or offset by the liabilities (claims made against the company’s assets by creditors, such as loans) and the equity (claims made against the company’s assets, such as shares held by shareholders). Double-entry bookkeeping seeks to balance the assets and claims against the assets. In fact, the balance sheet of a company is developed using this formula:

Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity

Profit and loss statements

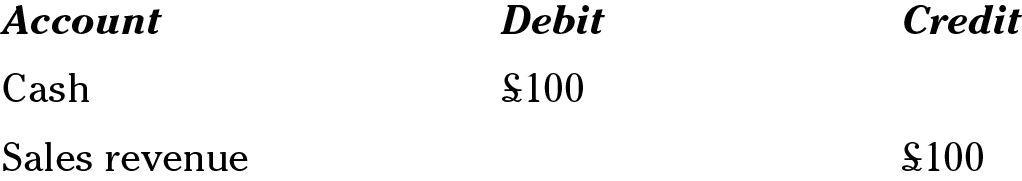

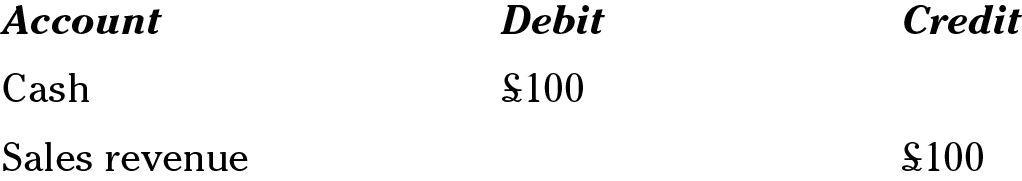

In addition to establishing accounts to develop the balance sheet and make entries in the double-entry system, companies must also set up accounts that they use to develop the income statement (also known as the profit and loss statement, or P&L), which shows a company’s revenue and expenses over a set period of time. (See Chapter 7 for more on revenue and expenses.) The double-entry bookkeeping method impacts not only the way assets and liabilities are entered, but also the way revenue and expenses are entered.

In this case, both the Cash account and the Sales Revenue account increase. One increases using a debit, and the other increases using a credit. Yikes – this can be so confusing! Whether an account increases or decreases from a debit or a credit depends on the type of account. See Table 4-1 to find out when debits and credits increase or decrease an account.

Table 4-1 Effect of Debits and Credits

| Account |

Debits |

Credits |

| Assets |

Increases |

Decreases |

| Liabilities |

Decreases |

Increases |

| Income |

Decreases |

Increases |

| Expenses |

Increases |

Decreases |

Make a copy of Table 4-1 and tack it up where you review your department’s accounts until you become familiar with the differences.

Digging into Depreciation and Amortisation

Depreciation and amortisation are accounting methods which track the use of assets that are used in the business and, as they age, their cost in the balance sheet is reduced. Tangible assets (physical assets such as machines or motor vehicles) are depreciated (reduced in value by a certain percentage each year to show that the tangible asset is being used up). Intangible assets (things like intellectual property or patents) are amortised (reduced in value by a certain percentage each year to show that the intangible asset is being used up).

For example, each vehicle owned by a company loses value throughout the normal course of business each year. Cars or lorries might be estimated to have five years of useful life. Suppose a company paid £30,000 for a car. To calculate its depreciation on a five-year schedule, divide £30,000 by 5 to get £6,000 per year in depreciation. Each of the five years this car is in service, the company records a depreciation expense of £6,000.

When the company makes the initial purchase of the vehicle using a loan, the company records the purchase this way:

In this transaction, both the debit and credit increase the accounts affected. The debit recording the car purchase increases the total of the assets in the motor vehicles account, and the credit recording the new loan also increases the total of the loans payable account.

The company records its depreciation expenses for the car at the end of each year this way:

The debit in this case increases the expense for depreciation. The credit increases the amount accumulated for depreciation. When you see Motor vehicles listed in the notes to the balance sheet, the line item Accumulated depreciation – Motor vehicles will be listed directly below the asset Motor vehicles and will be shown as a negative number to be subtracted from the value of the Motor vehicles assets. This way of presenting the information in the notes helps the financial report reader see quickly how old the assets are and how much value and useful life remain for the asset.

On the balance sheet itself, the net book value of all the tangible assets used in the business is shown. The net book value is the total cost of all of these assets less the total of all of the accumulated depreciation.

A similar process, amortisation, is used for intangible assets, such as patents. Just like with depreciation, a company must write down the value of a patent during the patent’s lifetime. Amortisation expenses appear on the income statement, and the value of the asset is shown on the balance sheet. The line item Patent is shown in the notes to the balance sheet with another line item called Accumulated amortisation below it. The Accumulated amortisation line shows how much has been written down against the asset in the current year plus in any past years. This gives the financial report reader a way to quickly calculate how much value is left in a company’s patents.

On the balance sheet itself, just like tangible assets, the net book value of all of the intangible assets used in the business is shown. The net book value is the total cost of all of these assets less the total of all of the accumulated amortisation.

Checking Out the Chart of Accounts

A company groups the accounts it uses to develop the financial statements in the Chart of Accounts, which is a listing of all open accounts that the accounting department can use to record transactions, according to the role of the accounts in the statements. All businesses have a Chart of Accounts, even if it’s so small that they don’t even realise they have one and have never formally gone about designing their Chart of Accounts.

The Chart of Accounts for a business will sort of build itself as the company buys and sells assets for its use and records revenue earned and expenses incurred in its day-to-day operations.

If you’re working inside a company and have responsibility for company transactions, you will have a copy of the Chart of Accounts, so you know which account you need to use for each transaction. If you’re a financial report reader with no internal company responsibilities, you won’t get to see this Chart of Accounts, but you do need to understand what goes into these different accounts to understand what you’re seeing in the financial statements.

Each account in a Chart of Accounts is given a number. This clearly defined structure helps accountants move from job to job and still quickly get a handle on the Chart of Accounts. Also, because most companies use computerised accounting, the software is developed with these numerical definitions. Some companies make up an alphabetical listing of their Chart of Accounts with numbers in parentheses to make finding accounts easier for managers who are unfamiliar with the structure.

The accounts in the Chart of Accounts will often appear in the following order:

Balance sheet asset accounts (usually in the number range of 1000–1999).

Balance sheet asset accounts (usually in the number range of 1000–1999).

Liability accounts (with numbers ranging from 2000–2999).

Liability accounts (with numbers ranging from 2000–2999).

Equity accounts (3000–3999).

Equity accounts (3000–3999).

Income statement accounts/revenue accounts (4000–4999).

Income statement accounts/revenue accounts (4000–4999).

Expense accounts (5000–6999).

Expense accounts (5000–6999).

In the old days, these accounts were recorded on paper, and finding a specific transaction on the dozens, or even hundreds, of pages used to record activity was a nightmare. Today, because most companies use computerised accounting, you can easily design a report to find most types of transactions electronically, by grouping them by account type, customer, salesperson, product, or almost any other configuration that helps you decipher the entries.

To help you become familiar with the types of accounts in the Chart of Accounts and the types of transactions in those accounts, we review the most common accounts in this section in the order in which you’ll most likely read them in a financial report. We assign the accounts numbers that are most commonly generated by computer programs, but you may find that your company uses a different numbering system.

The granddaddy of bookkeeping

Every transaction a company makes during the year eventually finds its way into the general ledger. Although companies often use the general ledger just for a summary of what happens in each of their accounts, some companies include details about specific transactions in their sub-ledgers. For example, accounts receivable is likely to be summarised in the general ledger by just putting the end-of-month totals for outstanding customer accounts. The actual detail of the transactions that took place during the month involving accounts receivables will be in an accounts receivable sub-ledger – often known as the Sales Ledger. In addition, accounting records will show details for each customer including what they bought and how much they still owe.

Asset accounts

Asset accounts come first in the Chart of Accounts, with the long-term accounts (those that the company will use in more than 12 months) listed before the most current accounts (those that the company will use in less than 12 months).

Tangible assets

Physical assets that you can touch are termed tangible assets and include long-term assets and current assets.

Long-term assets (also known as fixed assets) are assets that will be held for more than 12 months. The following are common long-term asset accounts:

Land: This account is used to record any purchases of land as a company asset. Companies should list land separately because it doesn’t depreciate in value like the building or buildings sitting on it do.

Land: This account is used to record any purchases of land as a company asset. Companies should list land separately because it doesn’t depreciate in value like the building or buildings sitting on it do.

Buildings: This account lists the value of any buildings the company owns. This value is always a positive number.

Buildings: This account lists the value of any buildings the company owns. This value is always a positive number.

Accumulated depreciation: This account tracks the depreciation of company-owned buildings. Each year the company deducts a portion of the value of the building based on the building’s costs and the number of years the building will have a productive life.

Accumulated depreciation: This account tracks the depreciation of company-owned buildings. Each year the company deducts a portion of the value of the building based on the building’s costs and the number of years the building will have a productive life.

Leasehold improvements: This account tracks improvements to buildings that the company leases rather than buys. In most cases, when a company leases retail or warehouse space, it must pay the costs of improving the property for its unique business use. These improvements are also depreciated, so the company uses a companion depreciation account called Accumulated depreciation – Leasehold improvements.

Leasehold improvements: This account tracks improvements to buildings that the company leases rather than buys. In most cases, when a company leases retail or warehouse space, it must pay the costs of improving the property for its unique business use. These improvements are also depreciated, so the company uses a companion depreciation account called Accumulated depreciation – Leasehold improvements.

Motor vehicles: This account tracks the cars, lorries, and other vehicles owned by the business. The initial value added to this account is the value of the vehicles when put into service. Vehicles are also depreciated, and the depreciation account is Accumulated depreciation – Motor vehicles.

Motor vehicles: This account tracks the cars, lorries, and other vehicles owned by the business. The initial value added to this account is the value of the vehicles when put into service. Vehicles are also depreciated, and the depreciation account is Accumulated depreciation – Motor vehicles.

Furniture and fixtures: This account tracks all the desks, chairs, and other fixtures a company buys for its offices, warehouses, and retail shops. Yes, these items, too, are depreciated, and the depreciation account is named Accumulated depreciation – Furniture and fixtures.

Furniture and fixtures: This account tracks all the desks, chairs, and other fixtures a company buys for its offices, warehouses, and retail shops. Yes, these items, too, are depreciated, and the depreciation account is named Accumulated depreciation – Furniture and fixtures.

Plant and machinery: A company uses this account to track any equipment purchased for the business that it expects will have a useful life of more than one year. This equipment includes computers, copiers, cash registers, and any other equipment needs. The depreciation account is Accumulated depreciation – Plant and machinery.

Plant and machinery: A company uses this account to track any equipment purchased for the business that it expects will have a useful life of more than one year. This equipment includes computers, copiers, cash registers, and any other equipment needs. The depreciation account is Accumulated depreciation – Plant and machinery.

Current assets are assets that will be used up in the next 12 months. The following are examples of current-asset accounts:

Inventory (or Stock): This account tracks the costs of products a company has available for sale, whether it purchases the products from other companies or produces them in-house. Although some companies use a computerised inventory system that adjusts the account almost instantaneously, others adjust the account only at the end of an accounting period.

Inventory (or Stock): This account tracks the costs of products a company has available for sale, whether it purchases the products from other companies or produces them in-house. Although some companies use a computerised inventory system that adjusts the account almost instantaneously, others adjust the account only at the end of an accounting period.

Accounts receivable (or Trade debtors): In this account, businesses record transactions in which customers bought products on credit.

Accounts receivable (or Trade debtors): In this account, businesses record transactions in which customers bought products on credit.

Cash in bank: Businesses use this account most often, depositing their cash received as revenue and their cash paid out to cover bills and debt.

Cash in bank: Businesses use this account most often, depositing their cash received as revenue and their cash paid out to cover bills and debt.

Cash on deposit: This account is where businesses keep cash that isn’t needed for daily operations. This account usually earns interest until the company decides how it wants to use this surplus cash.

Cash on deposit: This account is where businesses keep cash that isn’t needed for daily operations. This account usually earns interest until the company decides how it wants to use this surplus cash.

Cash on hand (or Petty cash): This account tracks the actual cash the company keeps at its business locations. Cash on hand includes money in the cash registers, as well as petty cash. Most companies have several different Cash-on-hand accounts. For example, a shop may have its own account for tracking cash in the registers, and each department may have its own petty-cash account. How these accounts are structured depends on the company and the security controls it has in place to manage the cash on hand. Companies always leave plenty of room for additions in this account category.

Cash on hand (or Petty cash): This account tracks the actual cash the company keeps at its business locations. Cash on hand includes money in the cash registers, as well as petty cash. Most companies have several different Cash-on-hand accounts. For example, a shop may have its own account for tracking cash in the registers, and each department may have its own petty-cash account. How these accounts are structured depends on the company and the security controls it has in place to manage the cash on hand. Companies always leave plenty of room for additions in this account category.

Intangible assets

Companies also hold intangible assets, which have value to the company but are often difficult to measure. The following are the most common intangible assets in the Chart of Accounts:

Goodwill: A company needs this account only when it has bought another company or unincorporated business. Frequently, the company that purchases another company pays more than the actual value of its assets minus its liabilities. The premium paid, which may account for things such as customer loyalty, exceptional workforce, and great location, is listed on the books as goodwill.

Goodwill: A company needs this account only when it has bought another company or unincorporated business. Frequently, the company that purchases another company pays more than the actual value of its assets minus its liabilities. The premium paid, which may account for things such as customer loyalty, exceptional workforce, and great location, is listed on the books as goodwill.

Intellectual property: Intellectual property is copyrights and patents, and written work or products for which the company has been granted exclusive rights. For example, the government grants patents to a company or individual that invents a new product or process.

Intellectual property: Intellectual property is copyrights and patents, and written work or products for which the company has been granted exclusive rights. For example, the government grants patents to a company or individual that invents a new product or process.

Having exclusive rights to a product allows a company to hold off competition, which can mean a lot of extra profits. Patented products often can command a much higher price.

Liability accounts

Money a company owes to creditors, vendors, suppliers, contractors, employees, government entities, and anyone else who provides products or services to the company are liabilities.

Current liabilities

Current liabilities include money owed in the next 12 months. The following accounts are used to record current-liability transactions:

Accounts payable (or Trade creditors): This account includes all the payments to suppliers, contractors, and consultants that are due in less than one year. Most of the payments made on these accounts are for invoices due in less than two months.

Accounts payable (or Trade creditors): This account includes all the payments to suppliers, contractors, and consultants that are due in less than one year. Most of the payments made on these accounts are for invoices due in less than two months.

VAT account: This account tracks Value Added Tax (VAT) collected for the government on sales by the company – known as output tax. It also records VAT that can be reclaimed on purchases – known as input tax. Companies record daily transactions in this account as they make sales and purchases. The balance on the account will then be payable to the government – usually at quarterly intervals.

VAT account: This account tracks Value Added Tax (VAT) collected for the government on sales by the company – known as output tax. It also records VAT that can be reclaimed on purchases – known as input tax. Companies record daily transactions in this account as they make sales and purchases. The balance on the account will then be payable to the government – usually at quarterly intervals.

Accrued payroll taxes: This account includes any Pay As You Earn (PAYE) income tax and national insurance (NI) that has been deducted from employees’ wages and salaries. It will also include the company’s national insurance contributions. The balance is paid over to the collector of taxes on a monthly basis.

Accrued payroll taxes: This account includes any Pay As You Earn (PAYE) income tax and national insurance (NI) that has been deducted from employees’ wages and salaries. It will also include the company’s national insurance contributions. The balance is paid over to the collector of taxes on a monthly basis.

Credit card payable: This account tracks the payments to corporate credit cards. Some companies use these accounts as management tools for tracking employee activities and set them up by employee name, department name, or whatever method the company finds useful for monitoring credit card use.

Credit card payable: This account tracks the payments to corporate credit cards. Some companies use these accounts as management tools for tracking employee activities and set them up by employee name, department name, or whatever method the company finds useful for monitoring credit card use.

Long-term liabilities

Long-term liabilities include money due beyond the next 12 months. The following are accounts companies use to record long-term liability transactions:

Loans payable: This account tracks debts, such as mortgages or loans on vehicles, that are incurred for longer than one year.

Loans payable: This account tracks debts, such as mortgages or loans on vehicles, that are incurred for longer than one year.

Bonds payable (previously known as Debentures): This account tracks corporate bonds that have been issued for a term longer than one year. Bonds are a type of debt sold on the market that must be repaid in full with interest.

Bonds payable (previously known as Debentures): This account tracks corporate bonds that have been issued for a term longer than one year. Bonds are a type of debt sold on the market that must be repaid in full with interest.

Equity accounts

Equity accounts reflect the portion of the assets that isn’t subject to liabilities and is, therefore, owned by the company shareholders. If the business isn’t incorporated, the ownership of the partners or sole proprietors is represented in this part of the balance sheet in an account called Owner’s equity or Capital. The following is a list of the most common equity accounts:

Share capital: This account reflects the nominal value of the ordinary shares in issue. Each share represents a portion of ownership. Even companies that haven’t sold shares in the public marketplace list the nominal value of their shares on the balance sheet. Each ordinary shareholder has a vote in the operation of the company.

Share capital: This account reflects the nominal value of the ordinary shares in issue. Each share represents a portion of ownership. Even companies that haven’t sold shares in the public marketplace list the nominal value of their shares on the balance sheet. Each ordinary shareholder has a vote in the operation of the company.

Preference share capital: This account reflects the nominal value of preference shares in issue. These shares fall somewhere between bonds and ordinary shares. Although the company has no obligation to repay the preference shareholder or to pay dividends, the preference shareholders always receive payment before the ordinary shareholder – even on a winding up of the company. If the dividends can’t be paid in a particular year for some reason on some preference shares, they’re accrued for payment in later years. Such preference shares are called cumulative preference shares. Any unpaid preference dividends must be paid before a company pays ordinary shareholders’ dividends. Preference shareholders don’t normally get a vote in the operation of the company but this depends on the company’s Articles. We deal with preference shares in more detail in Chapter 6.

Preference share capital: This account reflects the nominal value of preference shares in issue. These shares fall somewhere between bonds and ordinary shares. Although the company has no obligation to repay the preference shareholder or to pay dividends, the preference shareholders always receive payment before the ordinary shareholder – even on a winding up of the company. If the dividends can’t be paid in a particular year for some reason on some preference shares, they’re accrued for payment in later years. Such preference shares are called cumulative preference shares. Any unpaid preference dividends must be paid before a company pays ordinary shareholders’ dividends. Preference shareholders don’t normally get a vote in the operation of the company but this depends on the company’s Articles. We deal with preference shares in more detail in Chapter 6.

Share premium: All shares have a nominal value. If, when purchasing shares, the shareholder pays the company more than the nominal value, then the excess (or premium) is recorded in this account.

Share premium: All shares have a nominal value. If, when purchasing shares, the shareholder pays the company more than the nominal value, then the excess (or premium) is recorded in this account.

Retained Earnings: This account tracks the profits or losses for the company each year. These numbers reflect earnings retained rather than paid out as dividends to shareholders and show a company’s long-term success or failure.

Retained Earnings: This account tracks the profits or losses for the company each year. These numbers reflect earnings retained rather than paid out as dividends to shareholders and show a company’s long-term success or failure.

Revenue accounts

At the top of every income statement is the revenue brought in by the company. This revenue is offset by any costs directly related to it. The top section of the income statement includes sales, cost of goods sold, and gross margin. Below this section, before the profit and loss section, expenses are shown. In the following section we review the key accounts in the Chart of Accounts that make up the income statement (see Chapter 7).

Revenue

All sales of products or services are recorded in revenue accounts. The following are the accounts used to record revenue transactions:

Sales of goods or services: This account tracks the company’s revenues for the sale of its products or services.

Sales of goods or services: This account tracks the company’s revenues for the sale of its products or services.

Sales discounts: This account tracks any discounts the company has offered to increase its sales. If a company is heavily discounting its products, it may be competing intensely or interest in the product may be falling. A company outsider won’t see these numbers, but if you’re reading the reports prepared for internal management purposes, this account gives you a view of how discounting is used.

Sales discounts: This account tracks any discounts the company has offered to increase its sales. If a company is heavily discounting its products, it may be competing intensely or interest in the product may be falling. A company outsider won’t see these numbers, but if you’re reading the reports prepared for internal management purposes, this account gives you a view of how discounting is used.

Sales returns and allowances: This account tracks problem sales from unhappy customers. A large number here may reflect customer dissatisfaction which could be the result of a quality-control problem. These reports are not available to those outside the company but internal management financial reports show this information. A dramatic increase in this number is usually a red flag for company management.

Sales returns and allowances: This account tracks problem sales from unhappy customers. A large number here may reflect customer dissatisfaction which could be the result of a quality-control problem. These reports are not available to those outside the company but internal management financial reports show this information. A dramatic increase in this number is usually a red flag for company management.

Cost of goods sold (or Cost of Sales)

The costs directly related to the sale of goods or services are tracked in cost of goods sold accounts. Cost of goods sold is usually shown as a one-line item but includes the transactions from all these accounts.

Purchases: This account tracks the cost of merchandise bought by the company for sale. A manufacturing company has a much more extensive tracking system for its cost of goods that includes accounts for items, such as raw materials, components, and labour, that are used to produce the final product.

Purchases: This account tracks the cost of merchandise bought by the company for sale. A manufacturing company has a much more extensive tracking system for its cost of goods that includes accounts for items, such as raw materials, components, and labour, that are used to produce the final product.

Purchase discounts: This account tracks any cost savings the company is able to negotiate because of accelerated payment plans or volume buying. For example, if a supplier offers a 2 per cent discount when a customer pays an invoice within 10 days rather than the normal 30 days, the supplier tracks this cost saving in purchase discounts.

Purchase discounts: This account tracks any cost savings the company is able to negotiate because of accelerated payment plans or volume buying. For example, if a supplier offers a 2 per cent discount when a customer pays an invoice within 10 days rather than the normal 30 days, the supplier tracks this cost saving in purchase discounts.

Purchase returns and allowances: This account tracks any transactions involving the return of any products to the manufacturer or vendor because they were damaged during shipping or were defective.

Purchase returns and allowances: This account tracks any transactions involving the return of any products to the manufacturer or vendor because they were damaged during shipping or were defective.

Freight charges: This account tracks the costs of shipping the goods sold.

Freight charges: This account tracks the costs of shipping the goods sold.

Expense accounts

Any costs not directly related to generating revenue are considered expenses. Expenses fall into four categories: operating, interest, depreciation or amortisation, and taxes. A large company can have hundreds of expense accounts, so we don’t name each one but give you a broad overview of the types of expense accounts that fall into each of these categories:

Operating expenses: The largest share of expense accounts falls under the umbrella of operating expenses, which include advertising, subscriptions, equipment rental, property rental, insurance, legal and accounting fees, meals, entertainment, salaries, office expenses, postage, repairs and maintenance, supplies, travel, telephone, utilities, vehicle repairs, and just about anything else that goes into the cost of operating a business and isn’t directly involved in the cost of a company’s products.

Operating expenses: The largest share of expense accounts falls under the umbrella of operating expenses, which include advertising, subscriptions, equipment rental, property rental, insurance, legal and accounting fees, meals, entertainment, salaries, office expenses, postage, repairs and maintenance, supplies, travel, telephone, utilities, vehicle repairs, and just about anything else that goes into the cost of operating a business and isn’t directly involved in the cost of a company’s products.

Expenses that fall into this area, rather than into the cost of goods sold, relate to spending that isn’t specific to the sale of a particular product but to the overall operation of the company.

Interest expenses: Interest paid on the company’s debt is reflected in the accounts for interest expenses – from credit cards, loans, bonds, or any other type of debt the company may carry.

Interest expenses: Interest paid on the company’s debt is reflected in the accounts for interest expenses – from credit cards, loans, bonds, or any other type of debt the company may carry.

Depreciation and amortisation expenses: We discuss how depreciation is calculated in ‘Digging Into Depreciation and Amortisation’ earlier in this chapter. The process for amortisation is similar. The amount written off each year for any type of asset is tracked in the depreciation and amortisation accounts, and the expenses related to depreciation and amortisation in each individual year are shown on the income statement.

Depreciation and amortisation expenses: We discuss how depreciation is calculated in ‘Digging Into Depreciation and Amortisation’ earlier in this chapter. The process for amortisation is similar. The amount written off each year for any type of asset is tracked in the depreciation and amortisation accounts, and the expenses related to depreciation and amortisation in each individual year are shown on the income statement.

Taxes: A company pays numerous types of taxes. VAT is not listed as an expense because it is paid by the customers and accrued as a liability until paid. Taxes withheld from employees are also accrued as a liability and aren’t listed as an expense.

Taxes: A company pays numerous types of taxes. VAT is not listed as an expense because it is paid by the customers and accrued as a liability until paid. Taxes withheld from employees are also accrued as a liability and aren’t listed as an expense.

The types of taxes that become expenses for a company include the employer’s national insurance contributions and corporation tax. We talk more about taxes and company structure in Chapter 3.

Differentiating Profit Types

A company doesn’t actually make different kinds of profits, but it has different ways to track a profit and compare its results with those of similar companies. The three key profit types are gross profit, operating profit, and net profit. In Chapter 11, we discuss how these different profit types are used to test the viability of a company.

Gross profit: Reflects the revenue earned minus any direct costs of generating that revenue, such as costs related to the purchases or production of goods before any expenses, including operating, taxes, interest, depreciation, and amortisation. The gross profit isn’t actually part of the Chart of Accounts. You calculate the number for the income statement to show the profit made by your company before expenses.

Gross profit: Reflects the revenue earned minus any direct costs of generating that revenue, such as costs related to the purchases or production of goods before any expenses, including operating, taxes, interest, depreciation, and amortisation. The gross profit isn’t actually part of the Chart of Accounts. You calculate the number for the income statement to show the profit made by your company before expenses.

Operating profit: The next profit figure you see on the income statement. This number measures a company’s earning power from its ongoing operations. The operating profit is calculated by subtracting operating expenses from gross profit. Some companies include depreciation and amortisation expenses in this calculation, calling this line item EBIT, or earnings before interest and taxes.

Operating profit: The next profit figure you see on the income statement. This number measures a company’s earning power from its ongoing operations. The operating profit is calculated by subtracting operating expenses from gross profit. Some companies include depreciation and amortisation expenses in this calculation, calling this line item EBIT, or earnings before interest and taxes.

Others add an additional line called EBITDA, or earnings before interest,

taxes, depreciation, and amortisation. Accountants started using EBITDA in the 1980s because it provided analysts with a number that they could use to test profitability among companies and eliminated the effects of financing and accounting.

Companies don’t actually pay out cash for depreciation and amortisation expenses. Instead, depreciation and amortisation are an accounting requirement that comes into play when determining the value of assets.

Interest is a financial decision. A company has the choice to finance new product development or other major projects by selling bonds, taking loans, or issuing shares. If a company chooses to raise money using bonds or loans, it has to pay interest. Money raised by issuing shares doesn’t have interest costs. We talk more about this difference and the impact on a company’s profits in Chapter 12.

Taxes, believe it or not, are also an accounting game. Most corporations report different tax numbers on their financial statements than they actually pay to the government because of differences between tax law and GAAP. We explain this further in Chapter 6.

Net profit: The bottom line after all costs, expenses, interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation. Net profit reflects how much money the company makes. The company can pay out the profit to shareholders or it can reinvest the money in growing itself. Companies add money reinvested to the retained earnings account on the balance sheet.

Net profit: The bottom line after all costs, expenses, interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation. Net profit reflects how much money the company makes. The company can pay out the profit to shareholders or it can reinvest the money in growing itself. Companies add money reinvested to the retained earnings account on the balance sheet.

Understanding accounting methods

Understanding accounting methods Following debits and credits

Following debits and credits Differentiating between assets and liabilities

Differentiating between assets and liabilities.jpg)

Cash-basis accounting: Expenses and revenues aren’t carefully matched on a month-to-month basis. Expenses aren’t recognised until the money is actually paid out, even if the expenses are incurred in previous months, and revenues earned in previous months aren’t recognised until the cash is actually received. However, cash-basis accounting excels in tracking the actual cash available.

Cash-basis accounting: Expenses and revenues aren’t carefully matched on a month-to-month basis. Expenses aren’t recognised until the money is actually paid out, even if the expenses are incurred in previous months, and revenues earned in previous months aren’t recognised until the cash is actually received. However, cash-basis accounting excels in tracking the actual cash available. Accrual accounting: Expenses and revenue are matched, providing a company with a better idea of how much it’s spending to operate each month and how much profit it’s making. Expenses are recorded (or accrued) in the month incurred, even if the cash isn’t paid out until the next month. Revenues are recorded in the month the project is performed or the product is shipped, even if the company hasn’t yet received the cash from the customer.

Accrual accounting: Expenses and revenue are matched, providing a company with a better idea of how much it’s spending to operate each month and how much profit it’s making. Expenses are recorded (or accrued) in the month incurred, even if the cash isn’t paid out until the next month. Revenues are recorded in the month the project is performed or the product is shipped, even if the company hasn’t yet received the cash from the customer.

.jpg)