Chapter 15

Turning Up Clues in Turnover and Assets

In This Chapter

Tracking inventory

Tracking inventory

Counting inventory turnover

Counting inventory turnover

Measuring fixed assets turnover

Measuring fixed assets turnover

Assessing total assets turnover

Assessing total assets turnover

Testing how well a company manages its assets is a critical step in measuring how effectively a company uses its resources. Inventory is the most important asset used for generating cash for any company that sells a product.

Many factors directly impact the cost of selling a product. These factors include producing the product, purchasing the products or materials not produced in-house, storing the product until it’s sold, and shipping the product to the customer or store where it’s sold. And if the company doesn’t sell its product fast enough, the product may become obsolete or damaged before it’s sold.

In this chapter, we review the measures you can use to gauge how well a company manages its assets, especially its inventory and how quickly a company sells it.

Exploring Inventory Valuation Methods

A company must know the value of its inventory in order to complete its balance sheet. In addition, a company must set a value for the items it sold in order to include a cost of sales number (the amount of money spent to produce or manufacture products to be sold) on its income statement. Calculating that value depends on the method the company uses. Five different accounting methods are available for determining the value of inventory, and each one can result in a different net income (the amount of profit earned by the company).

These methods include

Last In, First Out (LIFO) inventory system: We have included LIFO because it is a term in common use; but under international standards, it’s not a permitted system. This system assumes that the last item put onto the shelf is the first item sold. Each time a product is purchased or manufactured to be put on the shelves, it costs a different amount. Usually, the cost goes up, so the last item put on the shelf is likely to cost more than the first item put on the shelf. Therefore, the goods sold first in the LIFO system are the highest-priced goods, which raises the cost of sales and lowers the net income. Stocking a shelf by leaving the older items in place and just adding the newly received products in front of it is a lot quicker. For example, hardware stores often use this method when restocking products that rarely change, such as hammers and wrenches.

Last In, First Out (LIFO) inventory system: We have included LIFO because it is a term in common use; but under international standards, it’s not a permitted system. This system assumes that the last item put onto the shelf is the first item sold. Each time a product is purchased or manufactured to be put on the shelves, it costs a different amount. Usually, the cost goes up, so the last item put on the shelf is likely to cost more than the first item put on the shelf. Therefore, the goods sold first in the LIFO system are the highest-priced goods, which raises the cost of sales and lowers the net income. Stocking a shelf by leaving the older items in place and just adding the newly received products in front of it is a lot quicker. For example, hardware stores often use this method when restocking products that rarely change, such as hammers and wrenches.

First In, First Out (FIFO) inventory system: This system assumes that the first items put on the shelf are the first items sold. The cost of goods purchased or manufactured differs each time they’re bought or made. Usually, prices increase, so in the case of FIFO, the first item put on the shelf is likely to have a lower cost than the last item put on the shelf. Because the first item is the one sold first, the cost of goods sold is most likely to be lower than in a company that uses the LIFO method. Therefore, the cost of sales is lower, and the net income is higher. For example, grocery stores have to consider spoilage, so they put the newly received products behind the older ones to be sure that the older products sell first before they spoil. It would be logical therefore for the grocery store to use the FIFO system.

First In, First Out (FIFO) inventory system: This system assumes that the first items put on the shelf are the first items sold. The cost of goods purchased or manufactured differs each time they’re bought or made. Usually, prices increase, so in the case of FIFO, the first item put on the shelf is likely to have a lower cost than the last item put on the shelf. Because the first item is the one sold first, the cost of goods sold is most likely to be lower than in a company that uses the LIFO method. Therefore, the cost of sales is lower, and the net income is higher. For example, grocery stores have to consider spoilage, so they put the newly received products behind the older ones to be sure that the older products sell first before they spoil. It would be logical therefore for the grocery store to use the FIFO system.

Average-costing inventory system: This system doesn’t try to specify which items sell first or last but instead calculates the average cost of each unit sold. This method gives a company the best picture of its inventory cost trends. Using this valuation method, the ups and downs of prices don’t impact a company’s inventory. Instead, the inventory value levels out through the year. The net income actually falls somewhere between the net income figures calculated based on LIFO and FIFO. It would be logical for a company to use this system if the items in a particular stock line were indistinguishable. For example, a company holding stock of a plastic moulding would not need to distinguish new stock from old stock because the mouldings would not deteriorate with time. A variation of the average-costing system is also used in continuous production systems – for example, where the company is producing petrol from crude oil.

Average-costing inventory system: This system doesn’t try to specify which items sell first or last but instead calculates the average cost of each unit sold. This method gives a company the best picture of its inventory cost trends. Using this valuation method, the ups and downs of prices don’t impact a company’s inventory. Instead, the inventory value levels out through the year. The net income actually falls somewhere between the net income figures calculated based on LIFO and FIFO. It would be logical for a company to use this system if the items in a particular stock line were indistinguishable. For example, a company holding stock of a plastic moulding would not need to distinguish new stock from old stock because the mouldings would not deteriorate with time. A variation of the average-costing system is also used in continuous production systems – for example, where the company is producing petrol from crude oil.

Specific-identification inventory system: This system actually tracks the value of each individual product in a company’s inventory. For example, car dealers track the value of each car in their stock by using this method. The net income is calculated by subtracting the cost of goods sold that have been specifically identified.

Specific-identification inventory system: This system actually tracks the value of each individual product in a company’s inventory. For example, car dealers track the value of each car in their stock by using this method. The net income is calculated by subtracting the cost of goods sold that have been specifically identified.

Market inventory system: This system sets an inventory value based on current market value. Companies whose inventory values can change numerous times, even throughout a day, usually use this valuation method. For example, dealers in precious metals, commodities, and publicly traded securities commonly use this method.

Market inventory system: This system sets an inventory value based on current market value. Companies whose inventory values can change numerous times, even throughout a day, usually use this valuation method. For example, dealers in precious metals, commodities, and publicly traded securities commonly use this method.

In most cases, companies use the FIFO, or average-costing inventory system. Specific-identification inventory is used only by companies that sell major items in which each item has a unique set of add-ons, such as cars or high-end computers. Therefore, each product being sold has a different cost of sale value. The market inventory system is used primarily by companies that sell marketable securities and precious metals.

When it comes to financial reporting, the accounting standard dealing with inventories IAS (International Accounting Standards) 2 states that inventories should be measured as the lower of cost and net realisable value. The accounting policies will tell you whether cost has been estimated using the FIFO, average-costing, or specific identification system. Net realisable value is the estimated selling price of the item of inventory less the estimated costs of completion and any costs necessary to make the sale. If net realisable value of any individual items of stock are below their cost then the notes to the accounts will disclose the aggregate amount of the write-down.

If you’re a company outsider, you won’t be able to get the details needed to calculate the value of the products left in inventory and will have to depend on the notional value on the balance sheet. In fact, many times, only the company insiders directly involved in inventory decision-making have access to cost details. Many companies consider actual inventory costs to be a trade secret, and they don’t want their competitors to know the details. Nonetheless, understanding what’s behind those numbers and how different inventory methods can impact the bottom line is important for understanding financial reports.

To calculate a company’s cost of sales, you must know the value assigned to the beginning inventory (which is the same as the ending inventory for the previous period and is also the same as the inventory number you find on the balance sheet). The beginning inventory is the number that is used at the beginning of the next accounting period, so any purchases made during this accounting period is added on to the beginning inventory. Finally, you need to know the number for the amount of inventory left at the end of the accounting period, which is called the ending inventory. Using those figures, here’s the formula for calculating the cost of sales:

1. Find the value of the goods available for sale.

beginning inventory + purchases = goods available for sale

2. Calculate the value of items sold.

goods available for sale – ending inventory = items sold

Tracking inventory

Inventory tracking methods can be a highly honed science for large corporations that involve extensive computer programming and management, or they can be as simple as taking a count of what’s in stock. Companies use one of the following two systems to keep track of their goods on hand:

Periodic inventory tracking: A company periodically counts inventory on hand to verify how many of the products are left on the shelves (if the company has retail outlets) and how many are left to be sold in the warehouse (or in cartons in the back of a store, if the company has retail outlets). Most companies that use a periodic inventory system do a physical count at least monthly and possibly as often as daily, depending on the company’s sales volume.

Periodic inventory tracking: A company periodically counts inventory on hand to verify how many of the products are left on the shelves (if the company has retail outlets) and how many are left to be sold in the warehouse (or in cartons in the back of a store, if the company has retail outlets). Most companies that use a periodic inventory system do a physical count at least monthly and possibly as often as daily, depending on the company’s sales volume.

Perpetual (or continuous) inventory system: Using this system, a company gets an updated inventory count after each sale. When you get a receipt that lists a long string of numbers next to each product’s name that you bought, the company most likely uses a perpetual inventory system. The long string of numbers is the tracking number assigned to the inventory in the computer system.

Perpetual (or continuous) inventory system: Using this system, a company gets an updated inventory count after each sale. When you get a receipt that lists a long string of numbers next to each product’s name that you bought, the company most likely uses a perpetual inventory system. The long string of numbers is the tracking number assigned to the inventory in the computer system.

You’ve probably been the victim of a company’s perpetual inventory system when you try to buy something at a store when the cash register is down. Many people have been in stores that couldn’t make a sale because the cash register was down, and the store had no way to manually handle the sale.

Applying Inventory Valuation Methods

To give you an idea of how inventory can impact the bottom line, we have created an inventory scenario to take you through the calculations for cost of sale value by using two key methods: FIFO and average costing.

In both cases, we use the same beginning inventory, purchases, and ending inventory for a one-month accounting period in March.

1. 100 (beginning inventory) + 500 (purchases) = 600 (goods available for sale)

2. 600 (goods available for sale) – 100 (ending inventory) = 500 (items sold)

Three inventory purchases were made during the month:

March 1 100 at £10

March 15 200 at £11

March 25 200 at £12

The beginning inventory value was 100 items at £9 each (assume, for simplicity in this illustration, that this is the same whichever system is being used).

FIFO

To calculate FIFO, you don’t average costs. Instead, you look at the costs of the first units the company sold. With FIFO, the first units sold are the first units put on the shelves. Therefore, beginning inventory is sold first, then the first set of purchases, followed by the next set of purchases, and so on.

To find the costs of sales, add the beginning inventory to the purchases that took place during the reporting period. The remaining 100 units at £12 are the value of ending inventory. Here’s the calculation:

Beginning inventory: 100 at £9 = £900

March 1 purchase: 100 at £10 = £1,000

March 15 purchase: 200 at £11 = £2,200

March 25 purchase: 100 at £12 = £1,200

Cost of sales = £5,300

Ending inventory:

From March 25: 100 at £12 = £1,200

In this example, the cost of sales includes the value of the beginning inventory plus the first two purchases on March 1 and 15 and part of the purchases on March 25. Those units remaining on the shelf are from the last purchase on March 25. The cost of goods sold is £5,300, and the value of the inventory on hand, or the ending inventory, is £1,200.

Average costing

Before you can use the average-costing inventory system, you need to calculate the average cost per unit.

100 at £9 = £900 (beginning inventory)

Plus purchases:

100 at £10 = £1,000 (March 1 purchase)

200 at £11 = £2,200 (March 15 purchase)

200 at £12 = £2,400 (March 25 purchase)

Cost of goods available for sale = £6,500

Average cost per unit:

£6,500 (cost of goods available for sale) ÷ 600 (number of units) = £10.83 (average cost per unit)

After you know the average cost per unit, you can calculate the cost of sales and the ending inventory value pretty easily by using the average-costing inventory system:

Cost of sales 500 at £10.83 each = £5,417

Ending inventory 100 at £10.83 each = £1,083

So the value of cost sales using the average-costing method is £5,417. This is the figure you would see as the cost of sales line item on the income statement. The value of the inventory left on hand, or the ending inventory, is £1,083. This is the number you would see as the inventory item on the balance sheet.

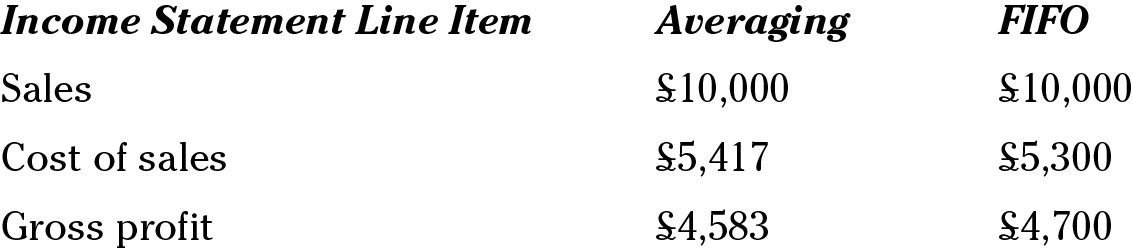

Comparing inventory methods and financial statements

Looking at the results of each method side-by-side shows you the impact that the inventory valuation method has on the income statement:

FIFO gives companies the lowest cost of goods sold and the highest net income, so companies that use this method know that their bottom lines look better to investors.

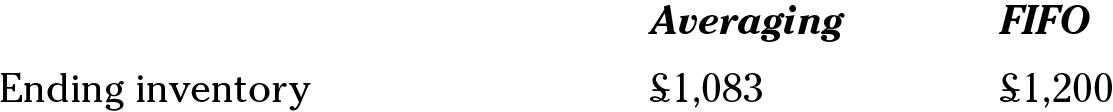

Results for the inventory number on the balance sheet also differ using these different methods:

Determining Inventory Turnover

The big question you should have for any company is how quickly is it selling its inventory and turning it into a profit. As long as that company turns over its inventory quickly, you probably won’t find outdated products sitting on the shelves. But if the company’s inventory moves slowly, you’re more likely to find a possible problem in the valuation of its inventory.

You use a three-step process to find out how quickly product is moving out of the door.

Calculating inventory turnover

Here’s the three-step formula for calculating a company’s inventory turnover:

1. Calculate the average inventory (the average number of units held in inventory).

beginning inventory + ending inventory ÷ 2 = average inventory

2. Calculate the inventory turnover (the number of times inventory is completely sold out during the accounting period).

cost of goods sold ÷ average inventory = inventory turnover

3. Calculate the number of days it takes for products to go through the inventory system, according to the accounting policies note to the financial statements.

365 ÷ inventory turnover = number of days to sell all inventory

In this calculation, you find out the number of days it took the company to sell all its inventory.

We use Tesco’s and Marks and Spencer’s 2007 income statements and balance sheets (see Appendix A) to show you how to calculate inventory turnover and the number of days it takes to sell that inventory. Both Tesco and Marks and Spencer use the lower of cost and market value inventory system to value their inventory, according to the accounting policy in their notes to the financial statements. Because they do this they cannot overstate the value of an item which for whatever reason has fallen below its cost price. This is particularly important in the garment industry where articles can go out of fashion and lose a lot of their original value. We can’t tell which costing system is used but it is likely to be FIFO.

Here’s the method to find out how quickly Tesco sells out all its inventory:

1. Find the average inventory.

Use the inventory on hand February 25, 2006, as the beginning inventory, and use the inventory remaining on February 24, 2007, as the ending inventory.

£1,464 (beginning inventory) + £1,931 (ending inventory) ÷ 2 = £1,698

2. Calculate the inventory turnover.

You need the cost of sale figure on the 2007 income statement to calculate the inventory turnover.

£39,401 (cost of sales) ÷ £1,698 (average inventory) = 23.2 (inventory turnover)

This figure means that Tesco completely sold out its inventory 23.2 times during 2007.

3. Find the number of days it takes for Tesco to sell out all its inventory.

365 (days) ÷ 23.2 (inventory turnover) = 15.7

Tesco took 15.7 days to sell out all its inventory. So every 15.7 days, Tesco turned over all its inventory. As an investor reading this report, you can assume that on average, Tesco sells all inventory on hand every 15.7 days. Remember, though, that won’t be true for every item that Tesco sells. Popular items, such as vegetables, may sell out and new stock may be needed every day, whereas less popular items, such as digital radios, may sit on the shelf for several weeks or more. This calculation gives you an average for all types of products sold.

Here’s the method to find out how quickly Marks and Spencer sells out all its inventory:

1. Find the average inventory.

Use the inventory on hand March 31, 2006, as the beginning inventory, and use the inventory remaining on March 31, 2007, as the ending inventory.

£374.30 (beginning inventory) + £416.30 (ending inventory) ÷ 2 = £395.30

2. Calculate the inventory turnover.

To do so, use the cost of sales number on the 2007 income statement.

£5,246.90 (cost of goods sold) ÷ £395.30 (average inventory) = 13.3 (inventory turnover)

This figure means that Marks and Spencer completely sold out its inventory 13.3 times during 2007.

3. Find the number of days it takes for Marks and Spencer to sell out all its inventory.

365 (days) ÷ 13.3 (inventory turnover) = 27.5

So Marks and Spencer sells all its inventory every 27.5 days. That figure is just about 12 days slower than Tesco’s, which may look like a significant difference, but remember that Marks and Spencer product mix of food to other products is very different to Tesco’s, which accounts for at least some of the difference.

What do the numbers mean?

Tesco takes 15.7 days and Marks and Spencer take 27.5 days to sell all their inventory (see preceding two sections), so they turn over their inventories approximately 23 and 13 times per year respectively. To judge how well both companies are doing, check the averages for the industry. You can do so online by obtaining a report from ICC Information Service using the Accounting Web Web site www.accountingweb.co.uk/icc.

Retailers, particularly efficient ones like these two companies, have very high inventory turnover ratios. To get a comparison with a company in a different industry, take Molins, a company in heavy engineering making factory plant and machinery. We would expect its inventory turnover to be very much lower than the retailers. It turns over its inventory only about 3 times in a year.

Investigating Tangible Fixed Assets Turnover

Next, you want to test how efficiently a company uses its fixed assets to generate sales, known as the tangible fixed assets turnover. Tangible fixed assets are assets that a company holds for business use for more than one year and that aren’t likely to be converted to cash any time soon. Tangible fixed assets include items such as buildings, land, manufacturing plants, equipment, and furnishings. Using the tangible fixed assets ratio, you can determine how much per pound of sales is tied up in buying and maintaining these long-term assets versus how much is tied up in assets that are more quickly used up. If the economy goes sour and sales drop, reducing variable costs is much easier than reducing costs for maintaining fixed assets. The higher the tangible fixed assets turnover ratio, the more nimble a company can be when responding to economic slowdowns.

Calculating fixed assets turnover

The fixed assets turnover ratio formula is

sales ÷ tangible fixed assets = tangible fixed assets turnover ratio

We show you how to calculate this ratio by using the net sales figure of Marks and Spencer’s and Tesco’s income statements and the tangible fixed assets figures from their balance sheets (see Appendix A). For both companies, you have to add several line items together, such as buildings, tools, equipment, and so on. In the case of Tesco and Marks and Spencer you add property plant and equipment and investment property. Here are the calculations.

Tesco:

£42,641 (sales) ÷ £17,832 (tangible fixed assets) = 2.4 (tangible fixed assets turnover ratio)

Marks and Spencer:

£8,588.10 (sales) ÷ £4,069.60 (tangible fixed assets) = 2.1 (tangible fixed assets turnover ratio)

What do the numbers mean?

At first glance, Tesco seems to use its tangible fixed assets more efficiently. A higher fixed assets ratio usually means that a company has less money tied up in tangible fixed assets for each pound of sales revenue that it generates. If the ratio is declining, that can mean that the company is over-invested in fixed assets, such as plant and equipment. To improve its fixed assets turnover ratio, a company may need to close and sell some of its plants and equipment that it no longer needs. Obviously in the case of these two retailers they have a huge amount of money tied up in property – their stores – so we should not expect this ratio to be very high.

You can tell whether a company’s fixed asset turnover ratio is increasing or decreasing by calculating the ratio for several years and comparing the results. The balance sheet includes two years’ worth of data. So in this example, you can request the financial statements for 2005. Then you’d have the data for 2007 and 2006 on the 2007 balance sheet, and you’d have the data for 2005 and 2004 on the 2005 balance sheet.

To get a comparison with another industry, Molins, an engineering company, has a tangible fixed assets turnover of 4.2.

Tracking Total Asset Turnover

Finally, you can look at how well a company manages its assets overall by calculating its total asset turnover. Rather than just looking at inventories or fixed assets, the total asset turnover measures how efficiently a company uses all its assets.

Calculating total asset turnover

The formula for calculating total asset turnover is

sales ÷ total assets = total asset turnover

We use information from Marks and Spencer’s and Tesco’s income statements and balance sheets to show you how to calculate total asset turnover. You can find the sales figure at the top of the income statement and the total assets at the bottom of the assets section on the balance sheet (Sometimes companies do not show this figure and you will have to add non-current assets to current assets to get the total assets figure). Here are the calculations.

Tesco:

£42,641 (sales) ÷ £24,807 (total assets) = 1.7 (total asset turnover)

Marks and Spencer:

£8,588.10 (sales) ÷ £5,381.00 (total assets) = 1.6 (total asset turnover)

What do the numbers mean?

Both Marks and Spencer and Tesco have similar asset ratios, so their efficiency in using their total assets to generate revenue is about equal. Both companies only hold about 16 per cent of their assets in current assets, which is a reflection of the business they are in with customers paying cash and the retailers taking credit from their suppliers.

Molins, who have to give their customers credit, has more than half its total assets in current assets, giving them the ability to pay their short-term bills.

A higher asset turnover ratio means that a company is likely to have a higher return on its assets, which some investors believe can compensate if you see the company has a low profit ratio. By compensate, we mean that the higher return on assets could mean increased valuation for the company and, therefore, a higher share price.