Chapter 19

Checking Out the Analyst–Company Connection

In This Chapter

Getting to know the analysts

Getting to know the analysts

Exploring the bond raters

Exploring the bond raters

Understanding the stock ratings

Understanding the stock ratings

Talking to analysts

Talking to analysts

Analysts regularly get into the act not by talking companies through their operational issues but by developing rankings that reflect a company’s value. The way analysts rate a company can have a major impact on that company’s share price and its value to investors. This chapter reviews the types of analysts and the way a company feeds financial information to them.

Typecasting the Analysts

You may not realise that several different types of analysts master various domains of financial analysis. These analysts, many of whom have completed an MBA and/or a gruelling testing process to get a qualification from bodies such as the Securities and Investment Institute, serve different roles for different people:

For large investment groups (such as mutual or pension funds): Determines whether a company’s stock price accurately reflects that company’s worth and whether the stock fills a particular niche that the group wants to fill in its overall portfolio management objectives.

For large investment groups (such as mutual or pension funds): Determines whether a company’s stock price accurately reflects that company’s worth and whether the stock fills a particular niche that the group wants to fill in its overall portfolio management objectives.

For financial institutions: Analyses a company’s debt structure and determines whether the company is bringing in enough money to pay its bills so that the institution can decide whether to lend the company money and at what interest that loan should be made.

For financial institutions: Analyses a company’s debt structure and determines whether the company is bringing in enough money to pay its bills so that the institution can decide whether to lend the company money and at what interest that loan should be made.

For brokerage houses: Provides individual investors with analysis about the companies they’re considering for their portfolio. Their reports are available to anyone who uses the brokerage house for stock transactions. Unless you have a very large portfolio and can pay the analyst, you won’t have an analyst work specifically for you. That’s why you need to read and analyse financial reports yourself.

For brokerage houses: Provides individual investors with analysis about the companies they’re considering for their portfolio. Their reports are available to anyone who uses the brokerage house for stock transactions. Unless you have a very large portfolio and can pay the analyst, you won’t have an analyst work specifically for you. That’s why you need to read and analyse financial reports yourself.

For bond rating firms: Reviews a company’s debt structure, financial health, and bill-paying ability in order to rate the bonds issued by the companies.

For bond rating firms: Reviews a company’s debt structure, financial health, and bill-paying ability in order to rate the bonds issued by the companies.

Reports from bond-rating companies are especially helpful because they focus on any debt problems the company may be facing. You can then check out the financial reports yourself and find the red flags more easily.

The way analysts view a company can make or break the value of the company’s stock. If a well-respected analyst writes a negative report after seeing the financial reports, the share price is guaranteed to drop at least temporarily. Red flags raised by analysts will help you find crucial details you should look for when reading a company’s financial reports.

.jpg)

The following sections describe the different types of analysts.

Buy-side analysts

Buy-side analysts work primarily for large institutions and investment firms that manage mutual funds, pension funds, or other types of multimillion-pound private accounts. Buy-side analysts are responsible for analysing stocks that portfolio managers are considering for possible purchase and placement in various portfolios managed by their firms. In other words, buy-side analysts’ bosses are major institutional buyers of stock. Some buy-side analysts work for mutual funds or pension funds directly; others work for independent analyst firms hired by the mutual funds or pension funds. You rarely see this type of analyst’s research available on the public market, but much of the information does trickle out in the financial press through statements made by fund managers.

Buy-side analysts write reports that help portfolio managers determine whether the stock fits the firm’s portfolio management strategy. Even a stock that most analysts would pan may get a positive report inside a buy-side analytical shop. For example, if the portfolio managers are looking for candidates for a value portfolio made up of stocks currently beaten down by the market but with good potential to rebound, buy-side analysts for this portfolio manager may recommend buying a share that has just lost half its value.

Sell-side analysts

As an individual investor, you are most likely see reports from sell-side analysts. These analysts work for brokerage houses or other financial institutions that sell shares to individual investors. You get reports written by these analysts when you ask your broker for research on a particular stock.

.jpg)

Many brokerage houses were more concerned about making money by selling shares than they were about helping investors put together share portfolios that met their goals and taking into consideration the amount of risk they wanted to take. Many investors lost 50 per cent or more of the money they had invested in shares during the 1990s and early 2000s before the stock market crashed. They were not well served by the analysts, who should have been accurately reporting the risks of investing in many of the companies whose financial reports they analysed for investors.

.jpg)

Brokerage companies used to avoid scandals and conflicts of interest by protecting themselves with what’s called a Chinese wall. Analysts kept their work separate from the investment banking division (which sells new public offerings of stocks or bonds and arranges mergers and acquisitions), and their remuneration wasn’t dependent on what business they helped to bring in. At some point in the past 20 years, this wall broke down, and sell-side analysts became partners with the investment banking side to help the firm make money. If a company won new investment banking business, it rewarded analysts with fees or commissions.

As an investor, you can quickly determine whether there’s a conflict between your interests and the financial interests of the brokerage house or analyst when you see the new disclosures required in any transaction that you undertake. Read the small print. You can also look at the brokerage house’s historical ratings for a company’s shares and see how successful it has been in accurately reporting the share’s value in the past. The City generally is sensitive to accusations of ripping off the ‘little people’ and therefore you should take action and complain if you ever think that a firm you are dealing with has infringed any of these guidelines.

.jpg)

Analysing the analysts

During the scandal-ridden technology crash of 2000, sell-side analysts working for brokerage houses were caught between the needs of their firms’ investment banking division (which sells new public offering of shares or bonds and arranges mergers and acquisitions) to help sell the new offerings handled by that division and the needs of their firms’ individual investors, who were clients of the salespeople. The investment banking side won, and individual investors got ripped off.

By writing glowing reports about the shares or bonds involved in potential or current investment banking deals, sell-side analysts helped pull in new investment banking clients and kept existing clients happy. While the brokerage houses made millions on investment banking deals, individual investors lost big chunks of their portfolios buying the recommended stocks that later went sour. Many of the stocks recommended by the sell-side analysts dropped dramatically in value after the market crash of 2000, leaving investors with ruined portfolios filled with worthless shares. Overall, investors lost billions.

New York State Attorney General Eliot Spitzer helped expose this entire mess by unearthing e-mails from superstar analysts like Henry Blodget of Merrill Lynch, who wrote great reports about stocks being sold by his investment banking divisions while privately calling these stocks ‘dogs’, ‘junk’, and ‘toast’. Spitzer charged that Blodget’s recommendations helped bring in $115 million in investment banking fees for Merrill Lynch. Blodget got rich, too. He took home about $12 million in compensation, according to Spitzer’s findings.

Merrill Lynch wasn’t the only company exposed during Spitzer’s investigation. Other firms caught in his net included Morgan Stanley Dean Witter & Co., and Credit Suisse First Boston. In fact, most brokerage houses on both sides of the pond that have an investment banking division got caught up in the scandal.

General principles of regulation

Brokers and bankers are regulated by the Financial Services Authority. Similar to the Security Exchange Commission in the US, the FSA holds its members to strict codes of practice. Unlike in the US, these regulations are not necessarily built into the law. But if you deal with an organisation that is regulated by the FSA you should find that it adheres to the following general principles as well as a whole raft of detailed requirements:

Integrity: A firm must conduct its business with integrity.

Integrity: A firm must conduct its business with integrity.

Skill care and diligence: A firm must conduct its business with due skill, care, and diligence.

Skill care and diligence: A firm must conduct its business with due skill, care, and diligence.

Management and control: A firm must take reasonable care to organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively with adequate risk management systems.

Management and control: A firm must take reasonable care to organise and control its affairs responsibly and effectively with adequate risk management systems.

Financial prudence: A firm must maintain adequate financial resources.

Financial prudence: A firm must maintain adequate financial resources.

Market conduct: A firm must observe proper standards of market conduct.

Market conduct: A firm must observe proper standards of market conduct.

Customers’ interests: A firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly.

Customers’ interests: A firm must pay due regard to the interests of its customers and treat them fairly.

Communication with clients: A firm must pay due regard to the information needs of its clients, and communicate information to them in a way which is clear, fair, and not misleading.

Communication with clients: A firm must pay due regard to the information needs of its clients, and communicate information to them in a way which is clear, fair, and not misleading.

Conflicts of interest: A firm must manage conflicts of interest fairly, both between itself and between a customer and another client.

Conflicts of interest: A firm must manage conflicts of interest fairly, both between itself and between a customer and another client.

Customer: relationships of trust: A firm must take reasonable care to ensure the suitability of its advice and discretionary decisions for any customer who is entitled to rely upon its judgement.

Customer: relationships of trust: A firm must take reasonable care to ensure the suitability of its advice and discretionary decisions for any customer who is entitled to rely upon its judgement.

Clients’ assets: A firm must arrange adequate protection for clients’ assets when it is responsible for them.

Clients’ assets: A firm must arrange adequate protection for clients’ assets when it is responsible for them.

Relations with regulators: A firm must deal with its regulators in an open and co-operative way, and must disclose to the FSA appropriately anything relating to the firm of which the FSA would reasonably expect notice.

Relations with regulators: A firm must deal with its regulators in an open and co-operative way, and must disclose to the FSA appropriately anything relating to the firm of which the FSA would reasonably expect notice.

Independent analysts

You may wonder if you can depend on any analysts out there. Well, the answer is yes and no. Certainly, some independent analyst groups – those that are not paid by a brokerage house or other financial institution but provide reports for a fee paid by people who want them – report on companies as well. The problem is that independent analyst groups work for people who can afford to pay them, meaning that you must have a portfolio of at least half a million pounds or you must be able to pay a large annual fee. Few individual investors meet the criteria to access the confidential reports of independent analysts because they can’t afford to pay the price to access them.

Many independent analysts do sell the reports through financial Web sites for a per-report fee to individuals who are researching a specific company. Your general rule about independent analysts’ reports should be to take what information you find useful, but be sure to do additional research on your own. The report you buy from the independent analyst on a particular company is one that was developed for one of the analyst’s clients and not specifically for you.

Bond analysts

Bond analysts are most concerned about the liquidity of a company and the company’s ability to make its interest payments, repay its debt principal, and pay its bills.

Bond analysts evaluate financial reports, management quality, the competitive environment, and overall economic conditions, but they do so with a cautious eye. If bond analysts make a mistake, they’re likely to err on the side of caution. Many people believe bond analysts actually provide the best source of objective company research available to individual investors. Most of these bond analysts work for independent bond rating agencies, as we describe in the next section.

Regarding Bond Rating Agencies

Bond ratings have a great impact on a company’s operations and the cost of funding its operations. The quality rating of a company’s bonds determines how much interest the company will have to offer to pay in order to sell the bonds on the public bond market. Bonds that are rated with a higher quality rating are considered less risky, so the interest rates that must be paid to attract individuals or companies that will buy those bonds can be lower. Bonds with the lowest ratings, which are also known as junk bonds, require companies that issue these bonds to pay much higher interest rates to attract individuals or companies that will buy those bonds.

You should be familiar with the three key rating agencies, all based in the US but all with subsidiaries in the UK and other European countries where you can find out what bond analysts think:

Standard & Poor’s: You’ve probably heard of Standard & Poor’s because of its S&P 500, which is a collection of 500 stocks that form the basis for a stock market index (a portfolio of stocks for which a change in price is carefully watched) in the US. The equivalent in the UK is the FTSE 100, a list of the biggest 100 companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. From time to time the FTSE 100 is revised adding some companies and taking others off. Many funds base their portfolios on this index, which is seen as one of the best indicators of stock market performance. When a company is added to the list, its share price usually goes up; when it’s taken off the list, its share price usually drops. You can find the list on the company’s Web site at www.ft.com. The credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s is at www.standardandpoors.com.

Standard & Poor’s: You’ve probably heard of Standard & Poor’s because of its S&P 500, which is a collection of 500 stocks that form the basis for a stock market index (a portfolio of stocks for which a change in price is carefully watched) in the US. The equivalent in the UK is the FTSE 100, a list of the biggest 100 companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. From time to time the FTSE 100 is revised adding some companies and taking others off. Many funds base their portfolios on this index, which is seen as one of the best indicators of stock market performance. When a company is added to the list, its share price usually goes up; when it’s taken off the list, its share price usually drops. You can find the list on the company’s Web site at www.ft.com. The credit rating agency Standard & Poor’s is at www.standardandpoors.com.

Moody’s Investor Service: Moody’s specialises in credit ratings, research, and risk analysis, tracking more than $30 trillion of debt issued in the US domestic market as well as debt issued in the international markets. In addition to its credit rating services, Moody’s publishes investor-oriented credit research, which you can access at www.moodys.com and navigate to the UK data.

Moody’s Investor Service: Moody’s specialises in credit ratings, research, and risk analysis, tracking more than $30 trillion of debt issued in the US domestic market as well as debt issued in the international markets. In addition to its credit rating services, Moody’s publishes investor-oriented credit research, which you can access at www.moodys.com and navigate to the UK data.

Fitch Ratings: The youngest of the three major bond-rating services is Fitch Ratings (www.fitchratings.com). John Knowles Fitch founded Fitch Publishing Company in 1913. The company started as a publisher of financial statistics. In 1924, Fitch introduced the credit-rating scales that are very familiar today: ‘AAA’ to ‘D’. Fitch is best known for its research in the area of complex credit deals and is thought to provide more rigorous surveillance than other rating agencies on such deals.

Fitch Ratings: The youngest of the three major bond-rating services is Fitch Ratings (www.fitchratings.com). John Knowles Fitch founded Fitch Publishing Company in 1913. The company started as a publisher of financial statistics. In 1924, Fitch introduced the credit-rating scales that are very familiar today: ‘AAA’ to ‘D’. Fitch is best known for its research in the area of complex credit deals and is thought to provide more rigorous surveillance than other rating agencies on such deals.

The UK also has many other bond rating and investor advice companies but they tend to be smaller and more specialised than the big three. The big three are so well established in the UK that, at the date of writing, they are the only bodies recognised by the Financial Services Authority as External Credit Assessment Institutions for the purpose of assessing risk when calculating capital resources of investment firms.

Each bond-rating company has its own alphabetical coding for rating bonds and other types of credit issues, such as commercial paper (which are shorter-term debt issues than bonds).

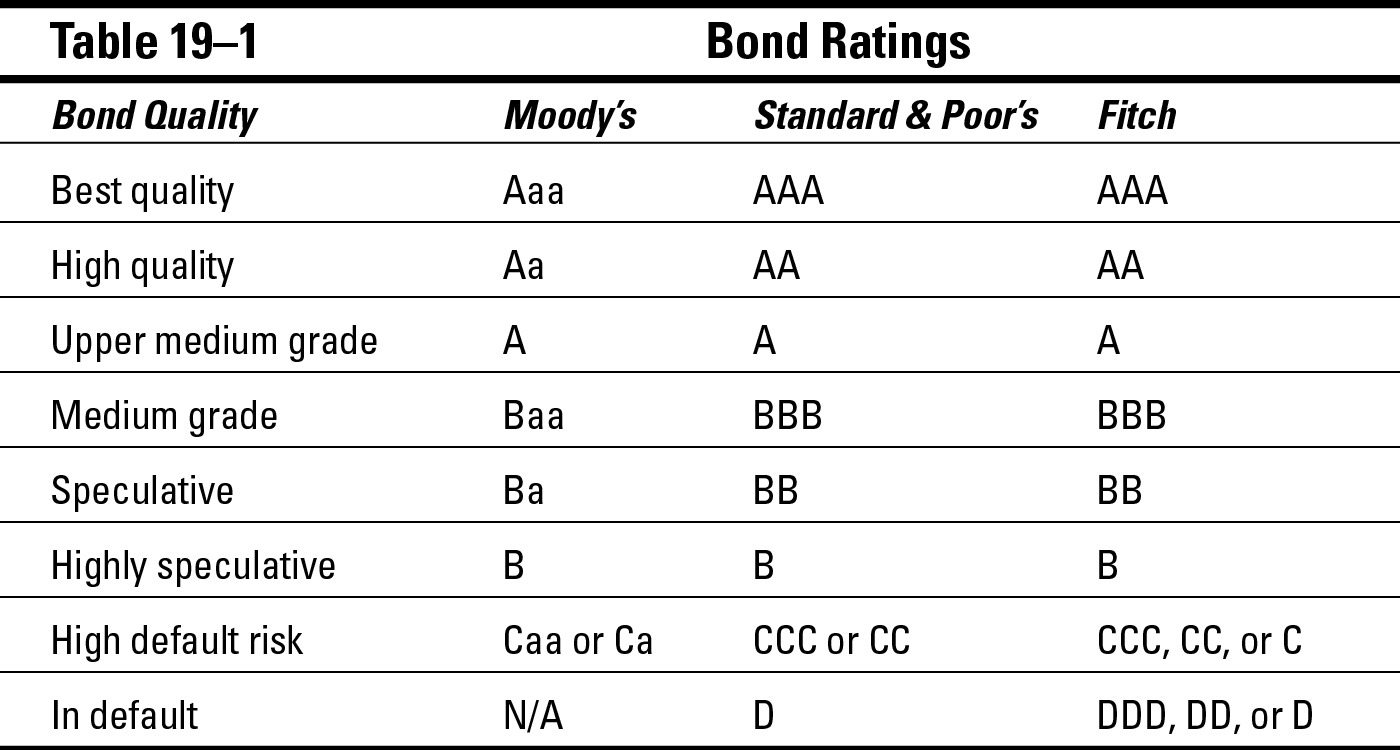

Table 19–1 shows how companies’ bond ratings compare.

Any company bonds rated in the ‘highly speculative’ category or lower are considered to be junk bonds. Companies in the ‘best quality’ category have the lowest interest rates, and interest rates go up as companies’ ratings drop. A key job of any company’s executive team is to feed bond analysts critical financial data to keep a company’s ratings high. Financial reports are one major component of that information.

Whenever a change occurs in the ratings, the rating services issue an extensive explanation about why the company’s ratings have changed. The press releases issued by the rating companies explaining these changes can be an excellent source of information if you’re looking for opinions on the numbers you see in the financial reports. You can find these press releases on the bond rating companies’ Web sites, as well as in news links on financial Web sites.

Building bond rating’s big guns

Standard and Poor’s is one of the premiere bond-rating firms. The company’s founder, Henry Varnum Poor, built his financial information company on the ‘investor’s right to know’. His first attempt at providing this type of financial information can be found in his 1860 book, History of Railroads and Canals of the United States, where he included financial information about the railroad industry. Today, Standard & Poor’s is a leader in independent credit ratings, risk evaluation, and investment research. It has the largest cadre of credit (bond and other debts) analysts in the world, totalling 1,250 around the globe.

John Moody started his rating service in 1909 and was the first to rate public market securities. He adopted a letter-rating system from the mercantile exchange and credit-rating system that had been used since the late 1800s. By 1924, Moody’s ratings covered nearly 100 per cent of the US bond market. It is now a global company servicing most countries in Europe. To this day, Moody’s prides itself on ratings based on public information and is written by independent analysts who don’t answer to the requests of bond issuers.

Delving Into Share Rating

Share rating is a much different game than bond rating. Although bond raters err on the side of caution, share raters, who for general public consumption are primarily sell-side analysts, seem to err on the side of optimism. You rarely find a share with a sell rating (a recommendation to sell the stock). In fact, when analysts recommend a hold rating (which is intended to mean you should hold the share, but probably not buy more) experienced investors understand it to mean sell.

.jpg)

Because various companies’ rankings may differ dramatically, you need to check out ratings from several different firms and research what each firm means by its ratings. A share that’s rated as a ‘market outperformer’ may sound pretty good. But in reality, it may not be a good investment, which may become clear when you compare rankings of other firms and find that they consider the company a ‘neutral’ or ‘hold’ stock.

Looking at How Companies Talk to Analysts

Companies not only send out financial reports to analysts, but they also talk with analysts regularly about their reports. Sometimes you have access to what is said by reading analysts’ responses to briefings or reading press releases.

Analyst briefings

Each time a company releases a new financial report, it usually schedules an analyst and press briefing to discuss the results. Usually, these briefings include the chairman, chief executive officer (CEO), and chief financial officer (CFO), as well as other top managers.

The briefings usually start with a statement from one or more of the company representatives and then are opened to those listening for questions. In most cases, only some analysts and sometimes the financial press are allowed to ask questions. Their reports on these briefings can be quite useful as the analysts and journalists should have probed for the companies’ weaknesses and then written them up.

In the US private investors can attend some of these briefings, or analyst calls, in person. The biggest advantage of listening to these briefings is that analysts ask questions of the executives that help you focus on the areas of concern in the financial reports. Turn to Chapter 20 to find out a little more about analyst briefings in the US.

Press releases

Companies often feed information to analysts through press releases. Luckily, individual investors can easily access these press releases on financial Web sites and the companies’ own sites. But remember that press releases are always going to be only what the company wants you to know. Learn to read between the lines and ask questions of the investor relations department for the company releasing the information if something concerns you.

The financial journalists’ comments on the press releases, which are written after the press release is issued, are probably a more important source of information. Companies put out a lot more press releases than there are stories printed in the paper about those releases. In fact, most press releases end up in the wastepaper basket, and you never see them in the newspaper because a financial reporter determines the information isn’t worth a story.

Road shows

Companies use road shows to introduce new securities issues, such as initial stock or bond offerings. Road shows are presentations by the company and its investment bankers to the analyst community and other major investors in the hope of building interest in the new public offering. As an individual investor, you’re unlikely to be able to attend these shows unless you’re a major investor.