Words can be like X-rays if you use them properly—they'll go through anything. You read and you're pierced.

The sense of place is as essential to good and honest writing as a logical mind; surely they are somewhere related. It is by knowing where you stand that you grow able to judge where you are.

Nobel Prize–winning Alice Munro set her Lives of Girls and Women in her native Huron County, Ontario. Stephen King's The Shining is set in the Colorado Rockies'-based Overlook Hotel, a fictional location inspired by a night he and his wife, Tabitha, spent as the only guests of the Stanley Hotel in Estes Park, Colorado. Both Beverly Cleary and her beloved Ramona Quimby grew up near Klickitat Street in Portland, Oregon. J. D. Salinger, born and raised in Manhattan, drops Holden Caulfield into the same setting in Catcher in the Rye.

There's impressive precedent for placing your novel in a location you're familiar with. Writers call on their personal experience to create vivid settings far more than they call on life experiences to create plot and even more so than they weave characters out of the people in their lives.

You should definitely mine your memories to build a cinematic setting.

I'm going to tell you how, but first, I want to make sure we're on the same page about setting and why it's important, because in my experience, most people have a one-dimensional idea of setting. For example, if I asked you where the musical Chicago is set, you'd tell me Chicago, and you wouldn't be wrong.

You wouldn't entirely be right, either.

Let me demonstrate.

Here, using ten words, I describe where I grew up:

Claw bangs stolen sweet wine summers

turkey farms snowy winters

If I'd simply told you I grew up in central Minnesota, you'd recognize the location but not really get the setting. I could even add a time frame, make it “central Minnesota in the '80s,” and you'd have a better idea of the terrain that produced me, but you wouldn't have anything substantial to hold onto, and for setting to work, it must engage the readers' senses and evoke a clear image.

Try it yourself. First, name the city or region where you grew up.

OK, now write the era.

Finally, in ten or fewer words, show rather than tell me the setting.

I imagine you didn't grow up a herd-following Midwestern country girl like me, but did your ten words create an image of your early life setting, one consisting of place, time, and mood? One that, if I closed my eyes, I'd be able to transport myself to because that's how specific your description was?

Excellent.

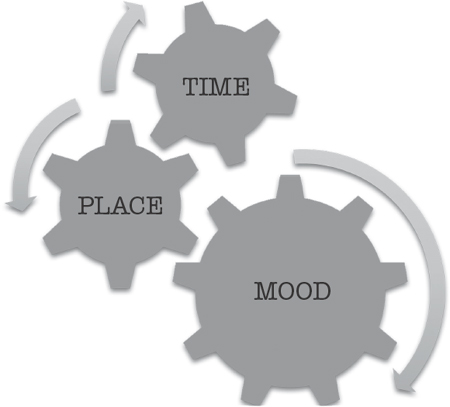

You need to do that in your writing, always. Setting in a narrative is not simply a place or a time. Cinematic setting in fiction is an interplay of both, plus mood, presented through facts (names of places, dates, etc.) as well as sensory (sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch) detail, which in turn interact to affect both writer and reader and, often, plot and character.

If I told you to imagine a hospital's smell, I bet you could call it up immediately: antiseptic, sharp, and depending on your personal experience, terrifying or comforting. Smell is the most evocative of the senses. Scientists believe the reason is that our olfactory bulb is right next to the amygdala and hippocampus, the parts of our brain that process memories and emotion. Vision, touch, and sound do not pass through the same area and so, scientists hypothesize, are not as connected in our memories.

Evoking smell is a great tool for writers. In fact, the phenomena of smell calling up vivid memories is referred to as the Proust Phenomenon after the scene in Proust's In Search of Lost Time where the character smells and tastes a madeleine cookie and is transported to his childhood. If you know the importance of sensory detail to creating vivid setting, and how effective it is in engaging your readers and connecting them to your story, then you'll wield setting like it's your job.

However, this Proust Phenomenon can also be uncomfortable verging on distressing, as many of the same setting tools used to evoke emotions in your readers will also evoke emotions and potentially memories in you. Again, smell is the worst offender, particularly for those suffering from PTSD. A scent that most would find unpleasant, say the smell of diesel fuel, might trigger a vivid wartime memory for a veteran, for example.

It isn't just smell, though, that can be a powerful connector. Mentally revisiting a location to write about it may activate a suppressed memory of something that happened at that location. The memory could be positive, but research finds that emotionally-charged experiences are more likely to be spontaneously remembered than non-emotional experiences.

For example, I have a friend who is a college speech teacher. She told me the story of a student who was so nervous for her first speech that she came to class in a full-length winter jacket. As it was February in Minnesota, this behavior wasn't odd. The problem came when the student removed her jacket and looked down to see she'd been so scared of public speaking that she'd forgotten to wear pants. I bet for the rest of her life, if she's ever in a room that smells like that classroom, she's plunged right into that mortifying memory. We all have our own versions of humiliation, shame, trauma, joy—any primal emotion—that we can and should call on to craft a vibrant setting, but tread cautiously in this area more than any other.

Rewriting your life lets you process your past so it can't sneak up on you.

This process is powerful, but it can also be painful, so I'm going to clarify that rewriting your life isn't a replacement for professional help. I was seeing a therapist every other week the year after Jay died, and I was sharing my experiences and fears with friends and family. To this day, I visit a good therapist every few months for a tune-up, more frequently if I need it. Living a healthy life is a marathon, not a sprint, and rewriting your life is a piece to the puzzle rather than a magic bullet.

Chapter 1, “The Science of Writing to Heal,” overviewed how writing therapy helps people to heal from past trauma. Writing about an emotionally impactful experience through the safety of fiction switches out one of three steps in the stimulus-significance-response pattern, allowing you more control in how you perceive and respond to memories as well as current situations.

If properly wielded, however, intentionally calling on past experiences to write compelling fiction allows you to gently access your crucible moments so that you can heal from them and use them in service of your story.

Vivid settings are foundational to compelling fiction. While settings tied to locations where you experienced something sad or traumatic or exceptional often pack an extra punch, it's not a requirement that you call on painful memories to write a fantastic setting. The settings just have to be richly portrayed, which, unless you have a secret superpower in this area, is easier to do if you've visited the places you're writing about.

As an example of how setting your novel in a familiar location allows you to bring added depth to your tale, check out this excerpt from Khaled Hosseini's moving A Thousand Splendid Suns, a novel that is in many ways an homage to his birthplace of Kabul, Afghanistan. He gracefully weaves time, place, and mood to create setting:

In the summer of 2000, the drought reached its third and worst year.

In Helmand, Zabol, Kandahar, villages turned into herds of nomadic communities, always moving, searching for water and green pastures for their livestock. When they found neither, when their goats and sheep and cows died off, they came to Kabul. They took to the Kareh-Ariana hillside, living in makeshift slums, packed in huts, fifteen or twenty at a time. That was also the summer of Titanic . . .

People smuggled pirated copies of the film from Pakistan—sometimes in their underwear. After curfew, everyone locked their doors, turned out the lights, turned down the volume, and reaped tears for Jack and Rose and the passengers of the doomed ship. (269)

In the preceding, notice how setting must be multidimensional. Effective setting takes place at the intersection of place (Kabul), time (summer of 2000), and mood (the black humor of people suffering from a drought obsessing over Titanic). Remove any one of those three legs, and the table falls flat.

Let me elaborate on how place, time, and mood intersect in well-written fiction.

Location is the most obvious component of setting. Laura Ingalls Wilder's autobiographical novel On the Banks of Plum Creek would have been a very different book if not set in Walnut Grove, Minnesota. Malcolm Lowry's Under the Volcano, which was ranked eleventh in Modern Library's 100 Best Novels list, was set in a fictionalized Cuernavaca, Mexico, where Lowry was living as he wrote. The story needed to be set in Mexico to capitalize on the character-building or -destroying effects of being a stranger in a strange land. Without it, it would have simply been another story of a drunk Brit.

When you're thinking about the primary location for your story, remember that it's not simply about an address. All three of the legs of setting—location, time, and mood—have two dimensions: your writing goal and how you want to achieve it. Think back to the beginning of the chapter and my description of where I grew up. My goal (the “where”) was to place you smack dab in central Minnesota, but central Minnesota is a different place for different people. I wanted to describe my central Minnesota, which I achieved (the “how”) by listing the defining characteristics that make me both love and despise my old stomping grounds. Here is more detail of how to choose the where and how of the location portion of your setting.

You might already know in what geographical place your novel will be set. The location may have sprung organically from the characters you want to bring in or the plot you want to follow, or maybe you started with a place and selected your concept backward from there. If, however, you haven't yet decided where you'll set your novel, I recommend choosing either where you live now or a location with strong resonance for you, as the story allows. You will be in fine company.

The next step is to decide how to convey that place with intimacy and poignancy. This sentence from Alice Munro's Lives of Girls and Women demonstrates the where (Jubilee) and the how of conveying Jubilee (“dull, simple, amazing, and unfathomable”):

People's lives, in Jubilee as elsewhere, were dull, simple, amazing, and unfathomable—deep caves paved with kitchen linoleum. (253)

To recap, it's not enough to simply state the location of your story. Whenever you mention place, make sure you include not only the where but the how.

Let me give one more example of the interplay of where and how. I wrote the first book in my young adult Toadhouse Trilogy because I wanted to write something my kids could read, and my semi-raunchy mysteries weren't cutting it. Plus, I wanted to capture a certain period in their lives. So, the original idea for that series sprang from the characters. Once I had chosen them, an older sister named Aine (an Irish name pronounced “Aw-knee”) who both resents and loves her little brother, Spenser, I decided to go meta and write a book about books. Specifically, I chose the concept that characters can actually travel inside of novels—A Tale of Two Cities, The Ramayana, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and so on.

I started with character, and that inspired plot.

I had only to choose setting.

Because I wanted the book to open with the children unknowingly residing inside a famous novel, I set them in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which dictated that my book open in Missouri. I've only barely passed through the Show Me state but for various reasons I wanted to set my novel there (one, really: I didn't want to get sued for setting my story in someone else's novel and so needed to choose one that was both famous and in the public domain; hence, Tom Sawyer), and so I began doing exactly what you should do if you need to set your novel somewhere you've never been: I started researching. I went online to learn about the weather, the geography, what plants grow there, and especially what the area I wanted to write about looked like. Google Earth is amazing for this, and free, as long as you have Internet access.

But all of that research just gave me the first dimension of location—the where. I still didn't know how to convey it. For that, I called on two pivotal childhood memories, one positive and one negative. The positive memory is of my sister and me playing hide-and-go-seek in the woods. We got so good at it that we'd blindfold ourselves (with sheets—never go small when you can go big) and hunt each other like clumsy animals. In this recollection, everything is dusted with a childhood, Alice-in-Wonderland sense of awe over the simple magic of being alive in a world where worms can dig, birds can fly, and enormous trees sprout from a tiny seed. The second memory is my recurring childhood nightmare of being terrorized on a riverbank.

Combining the what—Missouri and all its facts—with the how—the thrill and terror of being alone in the woods and by the river—resulted in this setting:

Her heart thudding, she curls herself small, like a chipmunk. The tight space reeks of mushrooms and a basement she can't remember. Through force of will and much practice, she steadies her breathing. That or her smell will surely give her away. Using tiny movements, she cradles moss over her raw elbow to mask the iron odor of the fresh wound. In this hunt, out of sight most definitely does not equal out of mind.

Overhead, a northern mockingbird trills, its song a repeated weep weep, weep weep.

Footsteps sound nearby almost immediately, surprisingly quiet.

Swish, swish.

She'd found cover in the nick of time. Outside her sycamore, the grass parts. Two sharp intakes seek her scent. Her heartbeat picks up, racing with the rat-a-tat of a woodpecker. She swallows her breath and melts deeper into the cave of the tree, becoming bark and branch.

It works. He steps past the gnarly sycamore with its girl heart.

Her clenched fists loosen.

She waits a handful of beats before poking her head out. No sign of him, just dense hardwoods forming a canopy so thick only ferns and horsebalm sprout beneath it, plus the occasional patch of grass where sunbeams are fighting their way through. The dappled light gives the forest an underwater quality, making it both vibrant and hazy. It smells humid, almost tropical. She must reach the river.

If you think something terrifying happens on the riverbank, just as it did in my recurring nightmares, you're right. And, for the record, that nightmare hasn't returned since I wrote about it. This is one of the gorgeous fruits of this process of rewriting your life—you get to process and release what no longer serves you.

As a side note, if you choose to write about an actual geographical location, know that there are two camps on this topic. One says don't set your novel in a real location because best case, you cheese off people because you didn't get it perfect, and worst case, you get sued. The other tells you to write the real so people can feel that connection, either because they can or they have visited the place. As someone who has done both, I'm not sure which camp I'd pitch a tent in, though if I am writing about something bad happening, I always make the place fictional. So, while my humorous mystery series is set in the real town of Battle Lake, Minnesota, where I lived for a number of years, all the murders happen in fictional businesses or houses. While I am not a lawyer and so have no legal advice to offer, my suggestion is that you protect yourself, always, and when in doubt as to whether or not to use a real place, err on the side of caution.

Another aside: if you want to work in social issues without being didactic, using place is a good way to do it. For example, if water issues are important to you, you could set the story in modern times near Lake Superior or Las Vegas or some location where the politics of water would naturally arise.

Like location, time has two dimensions in your fiction: the when and the how. The when is self-evident. The how, unless you're writing a story set in exactly your world and the time that you're writing in, requires research. Because The Toadhouse Trilogy opens in late 1800s Missouri, I needed to research the specifics of language, clothes, technology, and the customs of that period to convey the time. Here's an example:

After she and Spenser are inside, she locks the door that's never been locked, pulls the curtains tight over the windows, then distracts herself by bustling over to the cupboards.

“Cheese dreams okay for lunch?”

It's Spenser's favorite meal. He nods happily.

Aine slices four slabs of homemade bread and next unwraps the papered white cheese that Mondegreen buys in town. She cuts two slices and arranges them on the bread before slapping a generous pat of butter into the cast iron pan and holding a lit match over the gas burner.

Grilled cheese sandwiches were referred to as “cheese dreams” in the late 1800s, bread was homemade, cheese came wrapped in paper, and if you were lucky enough to have a stove that was not powered by wood, it was powered by gas or kerosene. All of those details are the “how” of the time period I chose.

It really is the small, specific details that capture time. If you are writing true historical fiction, note also that your readers will be sticklers for accuracy. Make sure to get it all right. If you're visual like me, I encourage you to tag or print out photos of time and place so that you can provide accurate descriptions. The New York Public Library has gone a long way toward helping writers obtain visual inspiration by putting nearly two hundred thousand (as of this writing) maps, photographs, postcards, and other amazing research into the public domain. You can access this resource by going online and searching for the library database.

Place is the where of your story; time, the when; and mood, the what. For my money, the mood is the most interesting leg in setting's three-legged structure. Ominous, funny, nail-biting, ironic, caustic, loving. Unless you're writing noir, gothic romance, or horror, your story's mood will change with the scene rather than be fixed to the story. Mood is a crucial component of a well-crafted narrative, and it calls upon all five senses.

In writing a scene for Toadhouse where I wanted to evoke terror, for example, I used sound, taste, touch, sight, and smell:

The knock, when it comes, echoes like a guillotine.

Rap rap rap. Rap rap rap.

A matched knocking, only louder, echoes through Aine's ribcage. Terror tastes like burnt chalk on her tongue. In the five years since they'd come to live in Grandma Glori's house on the edge of the woods, only two people besides Mondegreen have ever visited. Both times, before answering the door, Glori had warned them. Hear that sound? You don't ever answer it. For anyone.

No one has knocked other than those two times. Until now.

“Shush,” Aine whispers, unnecessarily.

Spenser is as white as bone. He's gripping the edge of the table. In a burst of insight, Aine realizes he has their mom's long, elegant fingers, the beautiful hands of a piano player. She hurries over and hugs him, her heart pumping in her skull.

“Quick, back here.” Aine pushes Spenser to a more protected spot behind the woodstove. He doesn't know the size of the space he is being shoved into, so she has to tuck his arms and legs in for him. His knee scrapes along a sharp corner, drawing blood.

“Will he be able to see me?” Spenser's voice is small and painfully frightened, the paper-thin sound of new ice cracking.

It breaks her heart to peel his hands off of her, but she has to.

Although calling on all five senses is important when you want to craft a particularly vibrant and memorable scene, don't go overboard. Setting should be authentic without being intrusive. If it slows down the forward momentum of the story or is thrown in simply for the sake of writing a setting, don't use it.

Another point to remember is that if quick movements are part of the time, place, or mood you're conveying, know your layout. Don't write an island in the center of the kitchen in one scene and have it be an open layout kitchen in the next. I recommend sketching floor plans for consistency, which the Map exercise at the end of this chapter will guide you in doing.

Ultimately, I hope you'll find creating setting an organic by-product of your writing and a chance to travel on a budget. I mean that seriously. When I succeed in building a truly cinematic setting, one that weaves place, time, and mood through a perfect balance of facts and sensory detail, I am living within the narrative as I write, smelling Chinatown as my character flees an assassin, tasting the glorious soup she slurps up after a day of hard labor, hearing the impossibly fragile music of flutes as she steals a kiss in the back of the orchestra room.

For this exercise, you're going to make (1) a setting circle and (2) a setting sketch for a potential scene in your novel. Your goal is to practice wielding both components of all three legs of effective setting and doing it invisibly so as not to pull your reader out of the story.

Here's what you do: think of a pivotal scene in the novel you're going to write, possibly the one that sets the whole story in motion. For my young adult book, the inciting incident happens on the porch of the grandmother's house, where she's struck down and the children are forced to flee. Sketch the layout for your own inciting scene. Then, fill out a setting circle for it. A setting circle is a handy-dandy visual organizer that allows you to brainstorm the time (when and how you will convey it), place (where and how you'll convey it), and mood (what and how you'll convey it) of a setting. I've used an example from The Toadhouse Trilogy to demonstrate how sketching the layout of and crafting a setting wheel for a pivotal scene could look.

Layout Sketch of My Scene

Setting Circle for My Scene

Here's the scene that resulted from that layout sketch and setting circle.

The blue weapons crawl off of him like worms and fly toward Glori. She drops the marble and curves her right hand into a claw. She clutches at her chest as if removing her heart and flings her hand at the woods. A roar of pain flies back.

“You can't help her,” Gilgamesh says, surprisingly close. “I will carry you if you don't move. Do not let her sacrifice be for nothing.”

But Aine cannot look away. Her mouth is still open in a soundless cry.

The blue maggots squirm toward the shack and her grandma. Then a strange thing happens. The salt ring stops them. They puff and squeal when they approach it.

Glori ignores them and sketches shapes in the air. The forms resemble Mondegreen's, intersecting lines and twisting ivy, except hers are a rainbow of colors and twice as large.

The breeze begins to hum. Glori keeps her eyes pinned on the forest, beyond Mondegreen's still form, attention absolutely focused. The trees begin to part. The roar in the woods has become primal and huge. The air around Glori is so thick with the shadows of shapes that it pulses.

Whatever has killed Mondegreen is about to emerge into the clearing.

Aine's legs move instinctively and she races toward her grandma. Despite her soul-deep terror, despite the certainty that if she follows Gilgamesh, she will be reunited with her mother, she can't leave Glori to fight that horrible, unseen creature by herself.

A bellow of pure hate echoes out of the forest.

Glori's eyes widen and the blood seeps from her face. She is staring straight south, into the oak forest. She has just laid eyes on the monster moving toward her. Glori turns to Aine, and Aine sees it clearly on her grandmother's face: surprise mixed with resignation. But no fear.

Later, she will remember being surprised there was no fear.

A proud smile flashes across Glori's face for an instant before it is replaced with a look of supreme concentration.

But time has run out.

The blue force in the forest has arched and focused until with a crack, it's shaped itself into an arrow that sears toward Glori. The air crackles and reeks of fresh lightning. The acid blue bolt screams directly toward her grandmother. Glori has time to snatch only one shape out of the air, only one final chance to save her own life.

“Scaoiligí!” She hurls the word at Spenser and Aine.

It hits Aine like a wall.

She drops to her knees.

The sensation is good, powerful, prickly. She smells a blast of cinnamon and allspice then breathes in air purely for the first time in five years. The vibrancy of freshness and green overpowers her senses. She raises her eyes to Grandma Glori and they lock stares. Aine is aware of a deep connection that lasts only for a moment.

It feels like love.

In that instant, scissoring blue blades hurtle through the air, flying directly over the spot where the salt lines did not meet because Jake had slashed the bag.

The rogue blades slice Glori in two.

Aine's legs go out from under her. She can't trust her eyes.

The mutilation happens so quickly that Glori's hand, still stretched into a claw, is hovering in the air for a moment after her top is separated from her bottom.

The giant marble falls to the ground first.

It's rained with hot blood.

Time stands still for a moment that lasts forever. Then the two halves of Glori's body drop to the porch with a terrible thud. The air is saturated with the metallic odor of new death.

Aine's eyes cloud and she is unable to breathe.

The suddenness, the permanence. She is stunned beyond reaction.

Grandma Glori has been murdered.

Sketch Your Scene Layout

Your Scene's Setting Circle