One thing that helps is to give myself permission to write badly. I tell myself that I'm going to do my five or 10 pages no matter what, and that I can always tear them up the following morning if I want. I'll have lost nothing—writing and tearing up five pages would leave me no further behind than if I took the day off.

I know some very great writers, writers you love who write beautifully and have made a great deal of money, and not one of them sits down routinely feeling wildly enthusiastic and confident. Not one of them writes elegant first drafts. All right, one of them does, but we do not like her very much.

Many people hate to revise.

I love it.

It's my opportunity to take this lumpy, stinky thing I coughed up and transform it into a novel. All the heavy lifting is done. All that remains is to move some paintings around and decorate. Yay! Editing also allows me to see inside my own head. This seems counterintuitive because I wrote the book, so clearly I already know what it contains, right?

Editing, for me, is an incredibly transformative stage of the turning fact-into-fiction process because during the writing period, you're releasing the story. During the editing stage, though, you're rewriting it. You get to mold it like clay, make it a different shape and color and texture, cut out what doesn't serve you, strengthen what you need more of, and generally seize control of the story, thereby commanding control of your life.

You become the boss of the narrative and, subsequently, your life.

If possible, give yourself a break between completing the first draft of your novel and editing it. I recommend at least two weeks during which you brag, celebrate, and make poor grocery choices. When you return to your manuscript, you'll see it with new eyes, which is literally what “re-vision” means.

You'll want to revise on two levels. One is content editing, which is big picture stuff. Maybe you have a character whom you discover doesn't bring anything to the narrative and you need to drop them. If you find yourself in this position, think about how to use that realization in your life. For example, I had a friend I shared a very formative period of my life with, but when we hit our forties, she no longer fit in the story I want to tell with my life. I wanted to live with more positivity and curiosity. She wanted to spend a lot of time living in the past and complaining about the present. After a few years of us choosing different directions, it became clear that remaining close friends didn't serve either of us. It was hard to step away from that friendship because we shared a past, and I love her. However, it was easier to put up a healthy boundary and end the relationship because I'd practiced cutting ill-fitting characters in my fiction.

Or, possibly you have a scene or chapter that isn't working or that needs to be moved. Hmm. Could the same be said of a habit or job that isn't fitting your life? Content editing takes care of this reorganization in your book and exercises the muscle that addresses the same in your life.

After you've done a round of content editing, you'll need to line edit. This is about dropping down to the sentence level and making sure there is constant flow. The life equivalent of line editing is literally looking for the best in each moment.

Content editing: big picture.

Line editing: sentence level.

They need to happen in that order, and both are necessary. Here's more detail on both and directions on how to apply them to your life.

You'll be unsurprised to learn that I have an acronym and an exercise to help you with content editing, which is also sometimes called substantive editing. I came up with it while drafting Salem's Cipher. The book's plot is complex, and the story is the longest I've ever written—over one hundred thousand words—with multiple points of view. Previously, I'd edited my manuscripts by giving myself a week or two off from them and then returning to read them straight through, noting inconsistencies and weak spots. This wouldn't work for editing Salem's Cipher. I needed to break that bad girl into scenes. Once I did that, I had to make sure every scene served a purpose and that they were organized in the best possible order.

Welcome to my brain, ARISE method.

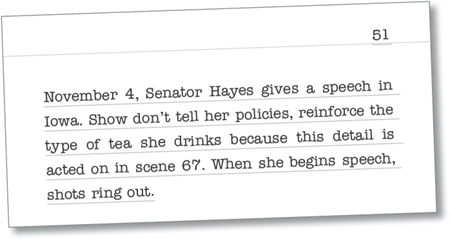

I came up with this method while using Scrivener, software designed specifically for writing novels. Scrivener allows a writer to summarize each scene or chapter on a virtual notecard, move it around as necessary (thus moving the scene associated with it), and color-code or otherwise mark each scene. The ARISE method works just as well with old-school 3″ × 5″ notecards. Here's how it plays out. First, you summarize your book scene by scene, one scene per notecard. Make sure each card is numbered in the order that the scenes appear in your novel. Scene 1 notecard has a “1” in the corner, Scene 2 notecard has a “2” in the corner, and so on. Here's a sample notecard for the fifty-first scene of Salem's Cipher:

If you want to buy colored notecards, I recommend taking this system one level deeper and assigning colors to the scenes as they make sense. If, for example, like me you have multiple viewpoints (not recommended for your first book), make all the scene cards from Character X's viewpoint pink, all the scene cards from Character Z's viewpoint blue, and so on. If, instead, your novel is heavy on subplot, make all the scene cards that deal with the main plot one color, and all the scenes that are more subplot-focused a different color.

Then, lay all your notecards out on the floor and jump right the hell into your book. I mean it. Get in there and move the cards around. Is there better flow if you do? Remove a card tied to a scene that has been bugging you. Does the book work better without it? Does each scene build on the one before it toward ever higher stakes? Are scenes intertwined, one inextricably connected to the next, or do they just sort of happen? If they appear disconnected from one another, how can you fix this issue?

Actually envision your story as a big movie playing around you or a symphony you're conducting. If you've color-coded your notecards, are the colors evenly distributed, or are they clotty and interrupting the flow? If they are overly clustered, rearrange. Is there a big hole somewhere in the narrative? Locate a blank notecard, scribble a scene summary on it, and see if it fills the void. Because you've numbered these notecards, you can always undo any changes quickly and cheaply, so be brave.

Go subterranean.

Once you have arranged, added, and deleted notecards in such a way that your narrative flows and is airtight with no missing or unnecessary scenes, it's time to ARISE. The foundation of this method is that every scene in your novel must serve at least one purpose. It must offer the reader

Obviously, the more the better, particularly if the only purpose the scene is currently serving is to provide information, which is the narrative equivalent of that guy who slows down to tell you that the store you're standing in front of, the only one in town that sells the widget you really need, is closed but will open again tomorrow at 9:00 a.m. He might be necessary, but wouldn't it be better if he was also being chased or was drop-dead gorgeous or leaves a mysterious clue behind or is holding a puppy?

Yes, of course.

Your job now is to go through each of your scene notecards, all still laid out in order (and if you've come up with a new order, pencil the updated numbers in the lower right corner, without erasing the original order you marked in the upper left corner), and scribble as many of the ARISE letters as pertain into the upper right corner of each notecard. If the scene has romance, pencil in an R. If it also has emotion, pencil in an E, and so on. If that scene has no letters, chuck it, no questions asked. If it fulfills only one letter, consider what you can add to it to give it at least two. Write a note to yourself on that card about what you're going to add to that scene. If a notecard has earned at least three letters, it's golden.

I'll give you an example from Salem's Cipher.

Here is scene 51, the same scene summarized in the notecard sample I shared. It is written from the point of view of Senator Gina Hayes, presidential candidate, who Salem does not yet know has the power to save it. Senator Hayes is about to give a speech in Iowa.

Gina Hayes looked up from her schedule. “Matthew, has someone tested the teleprompters?”

“Yes, but you won't need them.” Matthew didn't pause his typing to answer but did stop to issue a threat to the cable news anchor creeping closer to Hayes despite multiple warnings. With a single gesture, he also managed to get her pre-speech chamomile tea brought to her.

Hayes smiled as she sipped. American voters were worried they'd be electing Gina and her husband to run the country when in fact, they should be worried about the package deal of Gina and her assistant. Matthew had chosen her outfit (a slimming pantsuit in deep “power” red), her hair (“less of the matronly Martha, more Assertive Annie with a dash of Sexy Susie”), and her make-up (“Chop chop! I need her to look like she's actually slept since last May”). Hayes had chosen the content of her speech, however, and written most of it through the night, working with her team of speech writers.

The address hit the three points she'd based her campaign on: economic power, global stability, and environmental protection. This one also contained an Easter egg, something her speech writers had begged her not to include: a nod to the so-called kitchen table issues that had been so important to her as a law student in college and continued to define her. She would address women's reproductive freedom, gay rights, income inequality, the pay gap, the minimum wage, immigration reform, veteran's rights.

She would represent the people.

“Are you ready?” Matthew held his iPad in one hand and her mobile mic in the other.

Hayes nodded briskly and handed him the empty tea cup. “Always.”

Matthew appeared wistful for a moment.

“What is it?” Hayes asked.

“I hate to say it, but Charming Charlie was right. You look beautiful.”

Hayes actually laughed, a ruby-colored chuckle seldom heard in public. “You're not getting a raise, Matthew.”

He winked and stepped away, the melancholy smile still on his face. Hayes was escorted into the wide open arena, the applause deafening. Tens of thousands of people jumped to their feet, screaming, waving signs, some of them crying. Hayes walked to the center of the stage and held her hands in the air. The teleprompters to her left and right were suspended like thin prisms. The space heaters on the stage created a visible barrier against the frigid November air, a wavy storm front that Hayes had to stare through like a mirage to see her audience.

But it didn't matter. This is where she was supposed to be. These were the people she was fighting for. She let the cheers wash over her.

“Thank you for inviting me to your lovely stadium, Hawkeyes!”

Impossibly, the volume of the cheers rose.

Hayes' smile widened.

She had her mouth open to begin her speech when the first shot rang out, popping like a car backfire, the bullet piercing the mirage of the stage.

Two Secret Service agents were on top of Senator Gina Hayes' body before the second shot was fired.

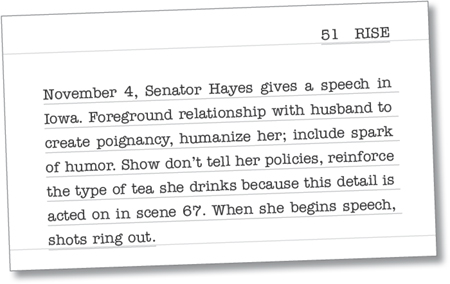

This example has Suspense (underlined) because you don't know if she lives or dies. It also provides important character Information (in gray), and so it technically was good enough. I wanted this book to be better than good enough, though. I also wanted the E, emotion, because I need readers to feel something for this character so it matters that she's in danger. And I wanted the R, romance or humor (in this case, more humor), because when I laid the notecards out, I realized the book hadn't had any R for a while, and as a result, it was growing dense. To revise, I first updated the notecard like this:

Then, I wrote the following and tacked it on to the opening of the scene. I've highlighted the humor in italics and the emotion in bold.

“You look beautiful.”

“Charles, it's the new millennium. Don't you mean I look powerful? Smart? Capable?” But Senator Gina Hayes' broad smile showed she was teasing. Her husband always said exactly the right thing. It was one of his gifts.

“I mean it.” He pulled her into an embrace rare enough that Matthew Clemens stopped juggling seven different appointments, hundreds of texts and emails, and a phone conversation with CNN to stare, agape. The three of them were backstage at Kinnick Stadium on the University of Iowa campus. Outside, an unusually plump crescent moon was crawling up the night sky, and the winter-washed air carried ice currents that nipped at noses and fingers. That didn't keep the record crowd of 35,000 supporters from bundling in parkas, hats, and scarves to hear a historic speech by who looked to be the first female president of the United States of America.

The election was in 6 days. News stations were predicting the highest voter turnout in history. Technicians, news crews, and security personnel bustled backstage. Since no moment of Senator Hayes life was private, at least two different cable stations were showing a live feed of her husband's embrace. She knew this, or at least guessed.

She didn't care.

She was going to steal these five seconds in her husband's arms, safe, grounded, a blink of selfishness before she stepped in front of thousands, millions with television and the Internet, and gave them everything she had. She'd been raised in the ideal of public service, taught by her father George that your life only had meaning if it helped others. She'd seen the sacrifices he'd made right up until his death of a heart attack two years earlier. She knew how proud he'd be of her, and that was one of the sparks that kept her fire burning.

Hayes pulled out of her husband's arms, letting her hand linger on his cheek for a moment. “Do I still look okay?”

He flashed the charming smile that had disarmed men and women—too many women—his entire political career. “You've never looked more powerful, smart, or capable.” He leaned close to her ear and whispered. “And I've never seen you look more beautiful. If you need help getting out of that suit later, you know where to find me.”

With a wink, he stepped back and let her hair and make-up crew complete their final touches. Hayes threw him one last glance before returning to work, wondering how he could still surprise her, still make her feel so attractive, even after all these years.

With those additions, the scene now included four of the five ARISE components: Romance/Humor, Information, Suspense, and Emotion. I knew I could move on to the next scene.

As another example, refer to Appendix E and check out Cisneros' scenes for The House on Mango Street. Every single scene in the book contains at least three of the ARISE components. There is emotion and information in every one of them plus humor in most and action, suspense, or romance in some. That's one of the reasons this book reads so well.

Once you've marked each card's ARISE status for your own story, step back one last time. Is all the romance or humor crammed into one act like it had been in my book before I expanded on scene 51? If so, spread it out.

Is the first scene written to elicit an emotional response from a reader? If not, make a note on the card how you will fix that. One trick is to have at least one person stressed or off balance in the opening scene.

Have you been led to believe that your novel doesn't need action or suspense because it's literary fiction? Consider that action is story movement and that there is suspense in the evolution of a human (will they make a different choice this time?), and find quiet ways to make sure you have both throughout.

How fun is the ARISE method? FUN.

Once you've created the notecards, subsequently reorganized the story, and then done an ARISE check for each scene, compile the note-cards in order and restructure your manuscript as necessary. The good news about content editing is that if you've applied the information in this book, you will have much less content editing to do than someone who just sat down to write. You'll have a map and a compass and will have worked out the major kinks before you even hit the road.

Still, even the most skilled drafter regularly cuts scenes and adds others. The best piece of advice I ever received on this front came from my friend, author and Boston Globe reviewer Hallie Ephron, who told me to keep a Saver file for each novel I write. I paste the scenes that I can't use into that file. It makes me feel better about slashing my darlings. I've used some of those Savers for short stories, but mostly, once they're out of the book and I've had a couple days to mourn, I realize they were crap to begin with.

I almost enjoy the line editing more than content editing. In line editing, you get to shine your jewelry, tightening your words and streamlining your sentences, making sure the story flows and glows. Besides putting the polish on something you've worked so hard on, line editing is also one of the few places in writing a novel where the rules are non-negotiable. The first requirement is that you must read your entire book out loud. It's weird, but trust me, you have to do it; our ears are much better proofreaders than our eyes. When reading out loud, you are listening for consistency in tone and voice, variety in sentence length, a hook at the end of each chapter, infrequent and well-chosen dialogue tags, conciseness, and correct spelling and grammar. I provide a handy checklist of these line editing requirements, including examples, at the end of this chapter.

If you elect not to publish this book or will be distributing to only a handful of close friends, applying the line editing checklist is plenty enough tweaking. If you intend to publish, however, you need one more level of editing before you send your book into the world: outside editing.

How this type of editing looks depends on your temperament and budget. Take me. I'm an introvert with more money than personality. Ha! That's only half true. I don't have a lot of money. But the idea of joining a writer's group of strangers is off-putting to me. That's why I hire a professional editor, a brilliant woman who lives in Oregon. She was referred to me by a New York City agent when I was shopping around my first novel. This agent promised that I was close and that if I worked with an editor, I'd push the manuscript over the top. She was right, and I've worked with the same professional for every book since.

There are wonderful editors available, and the best way to find them is to ask other writers for recommendations. This book's last chapter offers tips for meeting writers. If budget is an issue, if you are a social person, or if you simply like to workshop your writing (which is a valuable endeavor when you have a good critique group), I recommend joining or forming a writers group. You can locate one by searching online, putting out a call on social media, or by contacting your local library or college writing department. I've never belonged to one, but I am friends with successful authors who swear by their writing group, and I believe if you find or create a gang that's a good fit, it'll rocket your writing to the next level.

After all is said and done, let this editing process be a relief and a celebration.

In fiction as in life, what we throw away is at least as important as what we keep. Take charge of your story. Toss out what no longer serves it. Revel in what remains. Editing, more than any other part of the writing process, is psychological weightlifting. It's the push and pull between the story we think other people want to hear and the story down in our bones that we know we must tell. Our job is to get out of our own way and not clutter up the process with flowery words or inauthentic plot twists or overwrought love stories.

We have to peel away the noise to reveal the tale we're meant to tell.

I'm going to leave you with a story that best exemplifies this. A couple years ago, I had the pleasure of killing time in a green room with the legendary Sue Grafton, a tiny woman with a delightfully sharp tongue, author of the best-selling Kinsey Millhone series. Sue was a screenwriter before penning her first novel, and based on her terrible experiences, she's famously claimed that she will never sell her series to Hollywood (and believe me, they've asked) and will haunt her children if they defy that wish after she dies.

We were talking about the love/hate relationship we have with writing and where story ideas come from. She pulled out some Jungian psychology that has stuck with me ever since.

“Our stories come from shadow,” she said. “At least the ones worth telling.”

I nodded knowingly, but she's nobody's idiot and could see I had no clue what she was talking about.

“Shadow is our dark side, that bloody gunk that we're embarrassed about but that we all possess, the source of our inspiration and our evil. Our ego wants to steer the story, wants to tell us the book we're writing is wonderful and great and the world needs it, or that it's horrible and better never see the light of day. It's our shadow that we must listen to, though. Our shadow cuts through the crap and tells the truth. It's our job as writers to listen to it.”

Find your shadow and respect its whispers. The rewards you'll reap extend far beyond the written page.

Check for these requirements as you read your book out loud, line editing as you go.