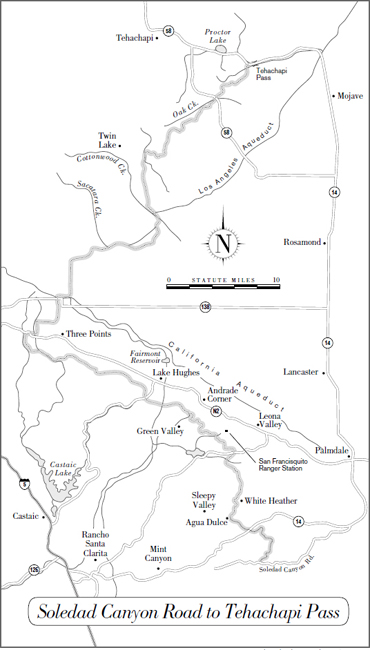

Big Bear Lake

Big Bear to Soledad Canyon Road

168.9 miles

This section consists of two distinct segments. The first segment (90 miles) starts in the transition-zone forest near Big Bear, but soon becomes largely a high-desert walk when it descends into the Mojave River drainage. It then crosses Cajon Pass and climbs the steep chaparral-covered south face of the San Gabriel Mountains. The second segment (80 miles) begins on the ridge of the San Gabriels, where it stays mostly high in transition-zone and Canadian-zone forests along the crest of the range. The PCT reaches its highest elevation in southern California (9,245 feet) at the junction with the side trail that leads to the summit of 9,399-foot Mount Baden-Powell. In the San Gabriel Mountains, plenty of trailhead parking areas enable you to fashion a hike of almost any length. The section ends with a 10-mile descent into Soledad Canyon.

THE ROUTE

Leaving the Big Bear area from Van Dusen Canyon Road, the trail is forested and shady—but not necessarily cool. Although the elevation starts out above 7,000 feet and stays above 6,000 feet for about 15 miles, the hot air of the Mojave Desert to the north seems to lie over the hillsides like a warming blanket. In these early miles, distances between water are reasonable (as always, within the context of southern California) and there is quite a bit of shade. But when the trail leaves the transition zone and its pine and oak forests, you can expect hot and dry hiking until you reach the crest of the San Gabriel Mountains, about 90 miles from the beginning of this section.

Big Bear Lake

The first 35 miles of trail north of Big Bear boast two of the best places to camp along southern California’s PCT. The first is 23.5 miles out, under a bridge that crosses Deep Creek. There’s a small sandbar with ample room for a couple of tents. The pool of cold, clear water feels delicious, and if you happen to be carrying a fishing rod and a license, there’s a good chance you’ll be eating rainbow trout for dinner. The second site, 9 miles farther, is at the popular Deep Creek Hot Springs.

Because these sites are only 9 miles apart, most thru-hikers will be able to stay at only one of them. But short-distance hikers can plan to stay at both. Warning: After the hot springs, the trail parallels Deep Creek, but there are very few places where you can easily get from the trail to the water. Don’t be fooled by how close together they look on maps! On leaving the hot springs, you’re back in the sunshine and scrub, so drink up before you go, and carry a couple of quarts with you.

The trail gets even drier after it leaves the dam, 46 miles into this section. So if you are hiking on past the Mojave River Forks Reservoir, be sure to fill your water bottles. Despite the gargantuan size of the dam, the Mojave River itself isn’t even enough of a river to reach the sea. For much of its course, the Mojave is what geologists refer to as an upside-down river, because its water sinks beneath the porous sandy soil of its riverbed and runs beneath the ground. And at some spots (different each year, due to varying levels of snowfall) it simply stops running altogether. Don’t let the dam dupe you into thinking that there’s actually a lot of water around.

Deep Creek

After some more hot and dry meandering, the trail reaches Silverwood Lake State Park, which has water, bathrooms, and a small store, all of which offer a welcome respite. Leaving Silverwood Lake, the trail climbs gently, then descends to Cajon Pass following a route that is mostly dry and very hot, with only intermittent shade. At Cajon Pass, the PCT crosses Interstate 15, which makes for a convenient place to start or end a hike. There is a restaurant, a motel, a gas station, and a convenience store at the interchange.

From Cajon Pass, the PCT climbs very gently for about 5 miles before getting serious about the task ahead: an ascent of the southern face of the San Gabriel Mountains. Some hikers consider this climb the most arduous in southern California.

Warning: Do not leave Cajon Pass without enough water to climb 5,000 feet and walk 22 miles. There is a reliable stream that runs through Cajon Pass; you can also get water at the services at the interchange. Strong hikers who can do the 22 uphill miles in one day need an absolute minimum of a gallon of water—and will wish they had more. Hikers who plan to break up the climb by camping will need as much as two gallons. The route is steep, waterless, and almost entirely exposed to the sun. Be walking by first light.

Immediately after gaining the crest of the San Gabriel Mountains, most long-distance hikers temporarily leave the PCT via the Acorn Trail to descend into the small community of Wrightwood for resupply. When they rejoin the trail, they find that walking along the crest of the San Gabriel Mountains is both easier and cooler than the climb to reach the ridge.

After gaining the crest, the trail stays largely above 7,000 feet for 25 miles, then seesaws between 4,900 feet and 7,000 feet for another 45 miles. Occasionally crossing and often paralleling the Angeles Crest Highway, the trail in the San Gabriel Mountains is easily accessible for day hikers and weekenders. It also boasts a series of primitive campgrounds, most of which are equipped with latrines, picnic tables, shade, and a fairly reliable water source (although springs start to dry up in late spring or early summer). Throughout the entire section, the footway is excellent, although trail signage near and around road crossings can occasionally be confusing.

The trail concludes this section by leaving the San Gabriel Mountains and descending into Soledad Canyon.

San Gabriel Mountains

WHAT YOU’LL SEE

Deep Creek Hot Springs

The Deep Creek Hot Springs sit on a fault, and their steaming waters give evidence of the continuing geological upheaval and broiling energy beneath the surface. (Consider, too, that the nearby dam of the Mojave River sits on the same fault!) Although the hot springs are only a couple of hundred yards off the trail, it’s not immediately obvious where they are. Some hikers have actually walked past them, so pay attention to your maps and your mileage. When you see an area that looks a bit greener than usual, you’re probably there, especially if there are people about. Don’t expect solitude—the springs are no secret. But there’s lots of room. Hot water seeps out of the hillside in several places, and using rocks, local hottubbers have dammed these trickles into a series of private pools, each big enough for several people. Some of these backcountry bathtubs are immediately adjacent to the cold waters of Deep Creek, so you can alternate between hot and cold bathing.

The guidebook warns about a rare hot-spring-inhabiting amoeba that can invade the human body through the nose, causing a potentially fatal disease called meningoencephalitis. Reportedly one hiker died in the 1970s and another became seriously ill. However, thousands of people visit the hot springs each year, so the risk, if any, is slight. You can minimize it by keeping the water out of your eyes, ears, and nose and taking your drinking water from upstream of the hot springs. For immersion bathing, you can always take a cold-water swim in the creek itself.

Cajon Pass

Like San Gorgonio Pass, Cajon Pass was one of the interior gateways that made east-west travel possible in southern California. The first documented crossing of the pass by Europeans was the de Anza expedition of 1775–76. Other notable pioneers included Mormon settlers, who were coming to make a home in the San Bernardino Valley, mine for gold, or volunteer as part of the Mormon Battalion for service in the Mexican War. Today the pass is crossed by I-15, a railroad, and the PCT.

A natural gateway, Cajon Pass provides an easy and logical passage between the mountains. But to climb into the mountains is another story.

The south-facing slope of the San Gabriel Mountains resembles the north-facing slope of the San Jacintos: stark, steep, and altogether uninviting—and indeed, for a similar reason: Both escarpments are the result of fault activity. Even John Muir was taken aback. “The whole range, seen from the plain, with the hot sun beating upon its southern slopes, wears a terribly forbidding aspect,” he wrote. “In the mountains of San Gabriel . . . Mother Nature is most ruggedly, thornily savage. Not even in the Sierra have I ever made the acquaintance of mountains more rigidly inaccessible. The slopes are exceptionally steep and insecure to the foot of the explorer, however great his strength or skill may be, but thorny chaparral constitutes their chief defense. With [little] exception, the entire surface is covered with it, from the highest peak to the plain . . . From base to summit all seems gray, barren, silent-dead, bleached bones of mountains, overgrown with scrubby bushes, like gray moss.”

The view is much the same today.

Just north of Cajon Pass, a little interpretive nature trail identifies some of the rugged, ubiquitous plants that hikers have been seeing since their first steps from the Mexican border.

Chaparral

The word chaparral is derived from chaparro, a Spanish scrub oak. Chaparral is not a single plant, but rather a community of plants that grow well in dry, rocky, nutrient-poor soil. The name was first used by Spanish settlers, who saw the similarity between this plant community and that of their native Mediterranean climate. Chaparral includes such non-oaklike species as sagebrush and manzanita (of which there are 28 species; manzanita is Spanish for little apple, and in spring you’ll see it blooming along the trail). Other common chaparral shrubs are chamise (also called greasewood because of its texture and flammability), mountain lilac, tobacco brush, ribbonwood, ceanothus, mountain mahogany, and poison oak. The shrubs often rise to the height of a hiker, blocking views. Sometimes the chaparral covering the hillsides can be as much as 15 feet tall.

True chaparral plants are well-adapted to heat and drought, with small, waxy leaves that reduce evapo-transpiration. Most varieties are evergreens. Like conifers, chaparral plants adapt to a short growing season by not having to waste time sprouting new sets of leaves. By midsummer they slip into near-dormancy to protect themselves from water loss. Other adaptations include extremely deep root systems and recessed stomates. (Burying the stomates deep in the plant tissue protects them from dry winds that could otherwise steal away water.) On some manzanitas, the leaves are an extremely light green, which better reflects the heat; other shrubs have shiny leaves to serve the same purpose.

Chaparral shrubs are also well-adapted to fire. Their seeds germinate after fire, and the shrubs can remain alive even when badly burnt, which gives them a competitive advantage over other species. Indeed, some species, like greasewood, actually encourage fire by being extremely flammable. Most unusual of all is chaparral’s ability to succeed itself: It is both a colonizing community and a climax community. But this fire tolerance makes chaparral dangerously vulnerable to wildfires, which can blaze out of control and threaten local towns. Even a spark from a carelessly discarded cigarette can cause thousands of acres to turn into an inferno. Don’t build fires when camping, and take special caution when using stoves, especially wood-burning stoves that require discarding ashes.

Chaparral plants are adapted for the dry life, but they know what to do with water. Given a moist year, these tough shrubs seize the moment and grow. In a matter of months, they can overrun a hiking trail with an obstacle course of spiky leaves, bloodthirsty thorns, and swordlike branches. Found on plains, mesas, and foothills, and common in southern California between 3,000 and 5,500 feet in elevation—especially on the desert side of mountains—chaparral is the most common plant community in California.

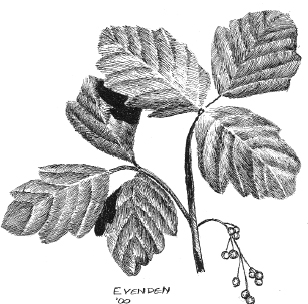

Poison Oak

Of all the plants that make up the ubiquitous chaparral community, one seems to dominate: poison oak. It’s not your imagination. Some botanists think that it is the most common chaparral plant in southern California. The American Medical Association has reported that acute dermatitis (in other words, an allergic skin reaction) due to contact with poison oak was responsible for 50 percent of the cases of workers compensation cases in California. Nationwide, this pesky plant (and its close cousins, poison ivy and poison sumac) causes more skin rashes than all other plants, household chemicals, and industrial chemicals combined.

Poison oak looks a little like poison ivy, with clusters of three unevenly lobed leaves. But poison oak can be hard to identify. It can grown as a shrub or a vine; sometimes it even looks like a small tree. Where the trail is cut into steep slopes, look carefully, because poison oak sometimes clings to the side of the hill and hangs down from above, where it can brush against a face or an arm.

Poison oak

It’s well worth your while to be able to identify the plant in all stages of its growth. If you’re a native easterner, don’t look for leaves that resemble those of the massive oak trees of an eastern hardwood forest. The shape of poison oak leaves can vary, but it tends to small, oval, and lobed, like the leaves of many western oaks. The oval-shaped leaves grow in triads and are usually thick and waxy-looking, especially in arid southern California, where their coating reduces transpiration and, therefore, heat loss. The size of the leaves can range widely. They tend to be smaller on hot exposed slopes, to reduce transpiration. In shady places, leaves are often quite a bit bigger. Leaves turn reddish in autumn, when the plant’s small, white flowers yield small, white berries.

It’s also important to be able to identify poison oak early in the season, before the leaves have sprouted. Poison oak branches (like poison ivy branches) are thin, flexible, and graceful looking. They often appear to be reaching out, then up, a little bit like the antlers of a deer. Sometimes the branches will hold leftover, shriveled white berries from the previous year.

All parts of the plant are poisonous. The irritant is a highly toxic substance called urushiol, which is found in berries, flowers, leaves, stems, and roots. Most people—by some estimates, 70 to 85 percent of us—are allergic to urushiol; the allergy tends to develop with repeated exposure. Most people who think they’re not allergic to poison oak will develop an allergy after enough exposure (the amount of exposure varying from person to person). So even if you think you aren’t allergic, it makes sense to try to avoid contact as much as possible.

Wearing long pants and long-sleeved shirts affords protection, but beware: You can also contact poison oak from clothing that has urushiol on it. Washing clothes in water deactivates the urushiol, but in dry southern California, this isn’t always an option for hikers. So even if you wear protective clothing, try to avoid plowing through a patch of poison oak.

There are some pre-exposure solutions, the idea being to put a chemical shield between your skin and the poison oak. But continually reapplying these solutions on a backpacking trip is impractical, especially if you can’t wash between applications. A better choice is to carry a small amount of anti-oak lotion (available at your outfitter), which can also be applied if you know you’ve been exposed (or, less effectively, later when a rash develops). Otherwise, popular home remedies include washing with alcohol or yellow laundry soap. Use cold water, and avoid rubbing, which spreads the irritant. You’ll know the poison oak rash when you get it: It itches like ten thousand mosquito bites, and in severe cases, it gets angry red with weepy blisters.

If you are very allergic, you might want to ask your doctor for a prescription of either a strong antihistamine (to stop the itching) or predni-zone (which speeds healing of the rash).

Mormon Rocks

It’s not just the chaparral that makes the southern slopes of the San Gabriels look so forbidding. Like the San Jacintos, the southern slopes of the San Gabriels owe their appearance to the action of the San Andreas Fault system, which cuts through Cajon Pass. Over time it has lifted the land on the north side of the fault to create the steep 7,000-foot escarpment that John Muir found so forbidding. A recent example of this uplifting occurred during the San Fernando Earthquake of 1971, which lifted the San Gabriel Mountains by an astonishing 6 feet.

Near Cajon Pass, there is also evidence of how the fault moves matter in an east-west direction. On the PCT, about a mile from Cajon Pass as you’re hiking north, the trail passes a conspicuous formation known as Mormon Rocks. Although to human eyes these rocks look perfectly fixed in place, they are on the move, being carried northeast by the fault at a rate of some 2 inches a year. The Mormon Rocks have traveled a long way to get here: They originated about 25 miles away, and if you follow the fault in a southwesterly direction for 25 miles, you’ll see the evidence. On the other side of the rift, there is a similar formation that geologists have determined was created at the same time and place as the rocks at Cajon Pass.

Since its formation some 30 million years ago, the San Andreas Fault system has continually rearranged the California landscape, in some cases moving matter as much as several hundred miles. In a sense, almost all of California seems to be on the move, headed for somewhere else. Geologists posit that if Los Angeles and San Francisco still exist a few million years from now, they’ll be standing side by side.

San Gabriel Mountains

Aside from the hot and dry 20-mile climb to the crest, the San Gabriels are not nearly as thornily savage to today’s hikers as they were to John Muir. Muir, remember, was wont to travel cross-country. In his day, maintained and graded recreational hiking trails did not tame steep slopes with gentle switchbacks and graded footways.

Back then the San Gabriels were prime habitat not for recreating humans, but for bears and bighorn sheep, which have now retreated into the most remote parts of the backcoutry, trying to escape the trails and roads that allow all manner of recreation use: not only hiking, but mountain biking, off-road driving, horseback riding, and skiing. (There are six ski areas in the Angeles National Forest; the thru-hiker resupply station of Wrightwood is a modest ski-resort town.) Paved roads bring the bulk of the visitors into these formerly impenetrable mountains. The Angeles Crest Scenic Byway runs between the towns of La Cañada and Wrightwood and is parallel tothe Pacific Crest Trail for some 35 miles. (Note: From some viewpoints along the highway, it is possible to see both the Pacific Ocean and the Mojave Desert.) Another paved road, the Angeles Forest Highway, intersects the PCT, linking the Angeles Crest Byway with Mojave Desert communities on the north side of the mountains, such as Palmdale and Lancaster. The frequent road crossings make it possible to plan short hikes of almost any duration.

These roads and trails have turned Muir’s thornily savage and rigidly inaccessible mountains into one of the most accessible and popular recreation areas in southern California. The Forest Service call the Angeles National Forest Los Angeles’s “backyard playground,” and a “truly urban national forest,” and claims that it attracts more than 32 million visitors each year. These distinctions are not likely to be attractive to backpackers and PCT thru-hikers, most of whom feel that if they wanted an urban playground, they could have stayed home. But not to worry: Despite the Forest Service’s description, hikers are unlikely to find the PCT overly crowded, especially once you walk a few miles from the trailheads.

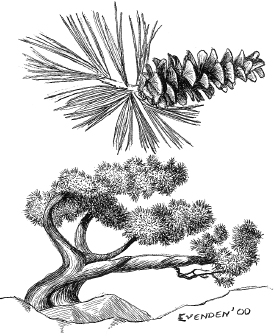

Limber pines atop Mount Baden-Powell

Mount Baden-Powell

The Angeles Crest boasts the highest point on southern California’s PCT—9,245 feet, just below the summit of 9,399-foot Mount Baden-Powell. A side trail leads about a quarter-mile (and the remaining 154 feet up) to the actual summit. Named after Sir Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Boy Scouts, Mount Baden-Powell is something of a pilgrimage site for Scouts. It’s also the terminus of the Scout-built Silver Moccasin Trail. Now designated as a national recreation trail, the Silver Moccasin Trail runs 53 miles through the San Gabriel Mountains and is a popular challenge for Scouts attempting to earn their hiking merit badge. For about 20 miles, it is contiguous with the Pacific Crest Trail. On the climb to Mount Baden-Powell (a well-trod trail, because the distance between parking lot and summit is only 4.2 miles), the Scouts have at random intervals built little markers showing distance and elevation. The distances are measured to the hundredth of a mile; elevations are given to the nearest foot. Doubtless such markers would become tedious over a long distance, but they last only a few miles. If you’re interested, take the opportunity to field-test your internal pedometer and altimeter. Thru-hikers might find that after several hundred miles on the trail, they have become fairly accurate judges of distance and elevation.

The quarter-mile side trail to the summit of Baden-Powell is well worth the little additional effort to get there. If not blocked by smog, the view from the peak gives you a chance to see several hundred miles of your past and future route, laid out before and behind you. On a good day the views extend forward all the way to Mount Whitney in the High Sierra and backward to the San Jacintos.

Limber Pines

In southern California, an elevation of 9,000 feet means that you’ve climbed into the Hudsonian zone. At sea level, you’d have to walk to northern Canada to find similar conditions. On smog-free days, the view from the summit of Mount Baden-Powell can be dramatic, but even more arresting are the oddly shaped limber pines that hug the wind-sheared high country. Named for the flexibility of their tough rubbery twigs, which can sometimes be bent into a knot, the limber pines atop Baden-Powell are thought to be more than 2,000 years old. Their flexibility is an advantage on the storm-buffeted slopes of exposed ridges. Flex ible trees are more able to bend with the wind; they are also better able to bend under large accumulations of snow.

Limber pines also grow at lower elevations—they are also found, for example, in Nebraska—and when their habitats are less exposed, they look a lot like ordinary pines, with symmetrical Christmas-tree shapes. But those that grow in the alpine zone allow themselves to be molded by the wind. The result is a tree with short, thick trunks and branches twisted into weird and fantastic shapes.

Limber pine

Soledad Canyon Road

In yet another of its precipitous changes of mood, the trail ends this section with a long descent into Soledad Canyon, where, at 2,200 feet, the terrain could not be more different from Baden-Powell’s cold summit.

The descent into the canyon is the same kind of long and winding descent PCT hikers are well used to by now, becoming hotter and drier the lower you go. From the trail, you can see the bottom long before you get there. Most inviting of all is the prospect of water. The Santa Clara River runs through Soledad Canyon, clearly visible from the mountainsides. No need to worry about a water shortage here: In addition to the river, the canyon contains a series of RV and trailer-park campgrounds that welcome hikers. There are even a few swimming pools, their turquoise waters shimmering an invitation that is visible from high up on the trail. The downside is the noise. Whistle-blowing trains run through the canyon all night long, so if you plan to spend the night, bring earplugs.

HIKING INFORMATION

HIKING INFORMATION

Seasonal Information and Gear Tips

This section is similar in climate and challenges to the section covered in chapter 2. Most of the first 90 miles can be hiked in the winter, although you may have some snow around Big Bear. The San Gabriels have snow during the winter, but generally are clear by May or June. At the higher elevations, the hiking season extends into summer—although the springs and seasonal water sources may not be running.

• Three-season hiking gear, including a rain jacket and warm (20- or 30-degree) sleeping bag, is recommended during the spring. During the summer, a lighter bag and fewer layers will suffice.

• In late spring, gnats can be an irritation during the day in the San Gabriels. A head net is a big help.

• There are several very dry stretches in this section. Have enough water containers to carry 6 or 7 quarts (more if you are overweight, out of shape, unacclimated to the temperatures, or plan to dry camp between water sources). Be sure to pay attention to your water supply when you leave Mojave Dam, Silverwood Lake, and, especially, Cajon Pass.

Thru-hikers’ Corner

• Unless you are hiking in extreme early season or in an especially high snow year, you are likely to be slowed by snow only on the slopes of Mount Baden-Powell.

• Summit Valley Country Store, on California Highway 173, is 0.3 miles off-trail just before the trail enters Silverwood Lake State Recreation Area. It’s a hiker-friendly resting place where thru-hikers are invited to put their packs on a scale and find out if what they’ve been telling folks about pack weight is true. Your picture, plus the results of the weighing, get put in the PCT album/register.

Best Short Hikes

• The first 46 miles (from Van Dusen Canyon Road to the Mojave River Dam) of this stretch of trail offers perfectly spaced campsites with water for hikers looking for a four-day backpack. Starting at Van Dusen Canyon Road, the mileages are 11 miles (to Holcomb Creek), 12 miles (to a campsite under a bridge spanning Deep Creek), 9 miles (to the Deep Creek Hot Springs), and 14 miles (to the dam).

• Short-distance hikers will also find plenty of good options in the San Gabriel Mountains. Frequent road crossings make it easier to plan short hikes in the San Gabriels than in any other of southern California’s ranges. The Angeles National Forest is crisscrossed by the Angeles Forest Highway and the Angeles Crest Scenic Byway. The PCT runs parallel to the Angeles Crest Byway for 35 miles, and there are lots of trailheads, making it possible to plan a hike of almost any length.

• The most popular day hike in this section of the PCT is the 4.2-mile climb from the trailhead on California Highway 2 to the summit of Mount Baden-Powell in the San Gabriel Mountains.

Resupplies and Trailheads

Big Bear City and Wrightwood are most commonly used.

Big Bear City (mile 0) is 3 miles off-trail via Van Dusen Canyon Road. It has restaurants, motels, laundry, a post office, and outfitters. The local fire department allows PCT hikers to camp in its yard. Post office: General Delivery, Big Bear City, CA 92314

Mojave River Dam (mile 46). There’s nothing here in the way of supplies, but this is a good trailhead for the four-day hike mentioned above.

Silverwood Lake State Recreation Area (mile 54.8) has a campground, shower, and store.

Cajon Pass (mile 68.4). The PCT crosses I-15 at Cajon Pass. A half-mile off-trail is an interstate exchange with a motel, a convenience store, and (a few hundred yards closer to the trail) a hiker-friendly restaurant that maintains a trail register.

Wrightwood (mile 89.6) on California Highway 2. Resupplying in Wrightwood requires descending on the 2-mile Acorn Trail, then walking another 1.5 miles on roads. Nonetheless, most long-distance hikers stop here because it’s the only convenient resupply point until Agua Dulce (chapter 4). Post office: General Delivery, Wrightwood, CA 92397

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press