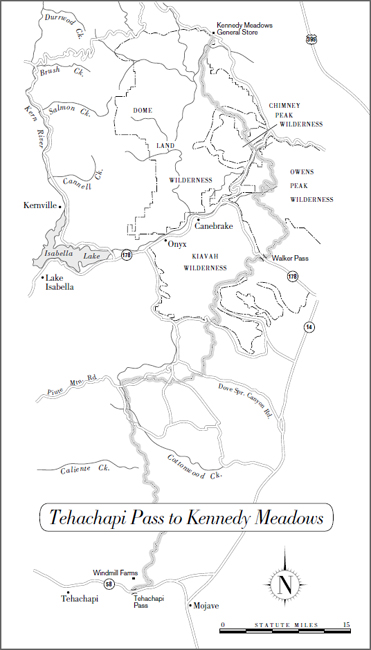

Antelope Valley

Soledad Canyon Road to Tehachapi Pass

109.9 miles

This section of trail is one of the most feared in southern California.

The Mojave Desert.

Desert with a capital D, as in dry, dust-bedeviled, desiccated, deadly. Up till now, everything else has been just practice.

At least, so go the rumors. The reality is not nearly so bad. In fact, some hikers find this section a welcome change, if a challenge. In the right season, it can be one of the highlights of a PCT hike.

The focus of all the hullabaloo is the Antelope Valley, which is the western arm of the Mojave Desert. To correct one misconception right off the bat, the Mojave is not an especially hot desert. Ecologists put it in a sort of middling category, a transition area between the hot Colorado Desert to the south and the cooler Great Basin Desert to the north.

And, to correct another misconception, not all of this section of trail is in desert. True to form, the PCT heads for the hills whenever possible. It spends far more time on chaparral-covered hillsides than it does on the sandy desert floors.

All that said, the difficulties here can be more severe than usual. For thru-hikers, who usually arrive in late May or early June, the temperatures in this “cooler” desert can be more than 100 degrees—and, as usual, ground temperatures can be a sole-scorching 150 degrees or even more. (In summer, ground temperatures can rise to 190—which might make you wonder whether ecologists should be required to walk across a desert before they get to tell the rest of us whether it’s hot or not.) The water situation is simply described: No natural water sources are reliable at any time of year. And if the trail often seems illogically routed and just plain ornery, that’s because it is. The route is the gerrymandered result of political compromise between a well-funded corporate landowner, which did not want the trail on its property, and the U.S. Forest Service, which simply wanted to get the trail finished and done with. As a result, this section was the last on the entire PCT to be completed. Its route has been criticized by many in the trail community. Criticized or not, the trail’s completion is marked by a monument in Soledad Canyon.

Ironically only a small percentage of the millions of people who annually hike on the PCT will ever see the monument. For the most part, this section is used by local outdoorspeople, long-distance hikers, or PCT section hikers. This section’s difficulties, both reputed and real, make is less than attractive as a destination in and of itself. That is unfortunate, because the Mojave offers a spring wildflower bloom that is well worth traveling to see.

THE ROUTE

Starting at Soledad Canyon Road, on the northern side of the San Gabriel Mountains, the trail follows a meandering route past parcels of private property before arriving on the paved main street that runs through the small ranching town of Agua Dulce. Although Agua Dulce has limited services (no motels or campgrounds, and in some years the post office has been shut due to a lack of personnel to run it), the town’s friendliness, hospitality, and involvement with the trail community, not to mention its well-stocked store, have earned it high marks as a thru-hiker trail town. It’s also one of only four towns on the PCT that the trail actually passes through. (Two others are in California: Belden, a trailer park settlement so small that it barely merits being called a town, and Seiad Valley, which is only marginally bigger. Cascade Locks, on the Oregon–Washington border, is the fourth.)

From Agua Dulce, the trail roller-coasters through the dry San Pelona Mountains, then passes close to Lake Hughes, a recreation area 2.2 miles off-trail that is a good rest and resupply stop. North of Lake Hughes, on a ridge along Leibre Mountain, you can sometimes see the Pacific Ocean. But sometimes not: Smog limits the number of clear days.

Dropping into the Antelope Valley, the trail changes character, reflecting southern California’s schizophrenic rural culture. Influenced by the proximity of the Los Angeles metropolitan area and the rapid growth of nearby towns like Palmdale and Lancaster, this part of the desert seems like a battleground between human civilization and the Mojave’s refusal to be civilized. Following not only trails, but also dusty dirt roads and occasionally (where there is no clear footway) a series of posts, hikers pass the artificial rivers of the California and Los Angeles Aqueducts, furiously flowing to meet the endless needs of southern California.

From any height of land, you can look down onto grids of empty roads that—despite names like Avenue C or 270th Street West—seemingly go from nowhere to nowhere in ruler-straight lines that disappear into the haze of heat. Street signs are riddled with bullet holes, and on the ground are piles of shotgun shells. Occasionally there’s a trailer dwelling surrounded with ATVs and cars that may or may not have been started in the last decade. Dirt-bike tracks are everywhere; occasionally you’ll see someone riding about, as likely as not wearing camouflage gear.

But there is also space, and—on the rare windless day—that big desert silence is as vast and encompassing as the star-studded nighttime sky. There is a fabulous assortment of varied vegetation, like the ridiculous-looking Joshua trees and the brilliant California poppies. And there is the glorious spring wildflower bloom that splashes the sand and gravel with a carpet of color.

This section is subject to extreme conditions: high winds, hot spring and summer temperatures, and winter frost. Bring plenty of water, because none of the water sources are reliable. An important water source is Cottonwood Creek (87.3 miles into this section and smack in the middle of the desert valley). The next reliable water, in Oak Creek Canyon, is 22.7 hot, dry miles away. Check the PCT hot line (1-888-PCTRAIL) for the most recent info on Cottonwood Creek.

Once across the desert valley, the trail remembers its affinity for higher country and climbs up into the Tehachapi Mountains, which are considered by some geologists to be the southernmost spur of the Sierra Nevada Range. Elevations rise to above 6,000 feet, offering good views of the San Gorgonio and San Jacinto Mountains to the south. The path follows its compromise route along the boundaries of the Tejon Ranch, and because the trail’s location was determined by politics and not the landscape, it often seems to defy the rules of commonsense trailbuilding. This section ends at Tehachapi Pass, the official beginning of the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

WHAT YOU’LL SEE

Trail History

Perhaps more than anywhere else on the PCT, this stretch of trail demonstrates some of the difficulties faced by trail mangers and public lands administrators in the construction of a long-distance footpath.

Most of the PCT boasts an extraordinarily scenic route. The trail has benefited from the fact that the major mountains ranges of California, Oregon, and Washington are part of our system of public lands. But there isn’t an unbroken corridor of public land from Mexico to Canada: About 12 percent of the PCT crosses private land. Much of that land is owned by large corporations that are active in such traditional western land uses as timber cutting (especially in Washington) and grazing. That is the case here, where the Tejon Ranch sits atop the crest of the Tehachapi Mountains, exactly where trail planners envisioned that the PCT should go. The ranch’s owners did not agree.

Like many rural landowners, the Tejon Ranch cited a litany of issues familiar to anyone who has worked to put a long-distance trail on the ground—whether it’s in the Appalachians, or Montana, or New Mexico, or southern California. Landowners fear that hikers will leave gates open, scare the cattle, bother the dogs, leave litter, start fires, pollute the water, vandalize buildings, and pave the way for hunters to come. In many cases, the reluctance is fueled by anti-government sentiment or by fear that if a landowner gives an easement to a trail, the government could come back in future years and request—or demand—more land.

In any case, for years the corporate-owned Tejon Ranch sat smack in the middle of the trail’s proposed route, and armed guards patrolled its perimeter, determined to keep trespassers out. Hikers, meanwhile, followed a temporary route through the middle of the Antelope Valley. This old route followed the Los Angeles Aqueduct straight across the desert toward the town of Mojave, then paralleled California Highway 58 up to Jawbone Canyon, where it turned west and climbed back into the mountains.

In 1988 most of the PCT was complete, and the 20th anniversary of the National Trail System Act brought the PCT publicity and increased public interest. Trail managers were determined to finish the trail and turned their attention to the pesky problem of the Tehachapis. Attempts to negotiate a right-of-way were rebuffed, and with no solution in sight, PCT managers did something they had never before done: In 1991 and 1992 they started condemnation proceedings to legally force the owners of the Tejon Ranch to allow the trail to pass through the property.

Condemnation is a powerful tool, but it has powerful, sometimes unwanted, repercussions. Forcing a landowner to sell property or an easement to the government often poisons relations between the trail and local communities for years. Realizing this, the PCT Advisory Council considered condemnation to be the tool of last resort. But with no compromise in sight, they felt they had no choice.

Facing with condemnation proceedings, the Tejon Ranch finally agreed to permit the PCT to pass through a small portion of its property. As a result, the PCT here follows some dirt roads, avoids ranch property whenever possible, and skirts along the fence line, following a bulldozed route that simply goes wherever the property line does—whether it makes trail sense or not. The guidebook calls the route a “hot, waterless, dangerous, ugly, and entirely un-Crestlike segment,” which might be overstating the issue. As with the rest of the southern California’s PCT, hiking through this largely waterless segment dictates careful planning and heavy water loads—but no more so than many other sections of trail to the south.

The route was clearly a compromise, but it was a route, and it was finished in time to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the National Trails System Act in 1993 by erecting a monument in Soledad Canyon. PCT managers and land administrators, as well as representatives from the Tejon Ranch, were on hand to celebrate the Golden Spike ceremony that marked completion of the PCT from Mexico to Canada.

Many hikers in the PCT community hope that in years ahead, a more pleasing route might still be established. In the meantime, hikers can help by being good guests. Follow posted regulations on ranch property, shut gates behind you, avoid making fires, follow minimum-impact guidelines, and pick up litter.

Los Angeles Aqueduct

In the Antelope Valley, hikers have the unusual experience of standing in the blazing sun, surrounded by cactus and Joshua trees, while hearing the roar of the artificial river of the Los Angeles Aqueduct running beneath their feet.

Spanish explorers first discovered the lazy, willow-choked Los Angeles River in 1769 and declared that the surrounding area had “all the requisites for a large settlement.” All, that is, except for a truly adequate supply of water. In 1781, the city of Los Angeles was founded. Today it has a population of more than 3 million people, and Los Angeles County (through which the PCT passes) is home to more than 16 million. Without the imported aqueduct water, the Los Angeles River could, by itself, support perhaps a quarter-million residents.

Built in 1913, the Los Angeles Aqueduct was the brainchild of William Mulholland, water superintendent for Los Angeles County at the turn of the century. Mulholland realized that Los Angeles was fast outgrowing its water supply. In 1905, Los Angeles voters approved a bond issue authorizing the city to buy land and water rights in Owens Valley, where spring snowmelt falls in torrents from Sierran peaks.

More than 200 miles from Los Angeles, the Owens Valley was, prior to the aqueduct, a well-watered agricultural area. With a water table only a few feet below the surface, the valley was one of the few areas in California where Native Americans practiced agriculture. Nineteenth-century emigrants also settled here to raise crops. But when the aqueduct, called Mulholland’s Ditch, opened in 1913, it took so much water that eventually even Owens Lake ran dry.

Seeing their farms become desiccated in this previously well-watered valley, Owens Valley farmers tried litigation, starting an era of water wars that combined the gunslinging drama of the Wild West with 20th-century big-city politics. Meanwhile, between 1913 and 1930, the population of Los Angeles grew from 200,000 people to 1,200,000, and the burgeoning city cast its eyes farther upstream, to the Mono Lake Basin, 105 miles north of Owens Lake. Taking too much water from the basin that fed the vulnerable habitat of Mono Lake almost destroyed this unique ecosystem, which is an important habitat for nesting birds and migratory waterfowl.

And still the city, and its thirst, kept growing. In 1970 the second Los Angeles Aqueduct was built. Today these two aqueducts bring in 430 million gallons a day and fuel 11 power plants. Los Angeles also gets water from northern California via the California Aqueduct (you’ll cross its open culvert about 32 miles north of Lake Hughes). Yet another aqueduct runs underground at San Gorgonio Pass, this one carrying water from the Colorado River. So it’s possible that some of the water you’ll drink in a Los Angeles County restaurant started its life as a snowflake in Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains or Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park.

Walking along the L.A. Aqueduct, thirsty hikers might sentimentally remember the water fountain at Snow Creek, which tapped into the water supply for Palm Springs back at the northern base of the San Jacinto Mountains. The Los Angeles Aqueduct is not nearly so generous. While its location is perfectly obvious—a dirt service road traces the exact path of the underwater river, and every so often you’ll see a capped siphon hole—the water is usually not accessible. In previous years, hikers were sometimes able to get water by removing the caps, but these days most of the caps are locked.

Mojave Desert

If you’ve been expecting a barren expanse of sand and cactus, you might be pleasantly surprised by the Mojave, especially if you happen to arrive during the peak of the spring wildflower bloom. Some biologists claim that the Mojave Desert is not an ecosystem unto itself, but is rather an ecotone, or edge, between the hotter Colorado Desert to the south and the colder Great Basin Desert to the North. Ecotones usually support large varieties of species—not only those endemic to each of the colliding ecosystems, but also those endemic to the unique environment that is formed where two different ecosystems meet. Adding to the biological diversity, the Mojave has great ranges in elevation (from below sea level to above 8,000 feet), and is proximate to other ecosystems, such as the southern Sierra, the Tehachapi Mountains, and the Coast Ranges. As a result, the Mojave boasts 250 species of annuals, 80 percent of which are endemics. In spring there can sometimes be as many as 70 plants per square yard; in wet years that number can exceed 400.

Thus valley oaks grow near Tehachapi Pass on the desert’s edge, next to Joshua trees and cactus. Some plants grow here that were commonly thought exclusive to Pacific slopes. A bright example is the California poppy, which puts on a profuse display in the Antelope Valley, often near dense groves of Joshua trees. Plants growing here are a mixture of cold and hot desert species; often there will be an upper story of shrubs and a lower story of grasses and cacti.

Plants and animals here cope with the usual dryland challenges. Much of the Mojave Desert receives less than 5 inches of water a year, most of which falls in winter, sometimes as light snow. Despite the presence of the Mojave River, there is no outlet from the Mojave to the sea. The land is so dry that any water that falls is quickly absorbed by the porous soil. Compounding the problem are the Mojave’s trademark high winds, which increase evaporation, stealing away much of the water that does manage to fall. Other factors that desert species must somehow adapt to include high salinity and alkalinity, scarce nutrients, frequent frost, and poor drainage.

Geologically as well as ecologically, the Mojave is one of America’s most varied deserts, with rock forms and landscapes that show evidence of dramatic geological processes. Bounded by the Garlock and San Andreas Faults, this is an area of seismic activity. It is also highly mineralized. Over the last hundred years, miners have tunneled the earth in search of gold, silver, tungsten, iron, copper, lead, zinc, molybdenum, antimony, tin, uranium, and thorium. The Mojave is also one of the greatest borax-producing areas in the world

The PCT crosses the Mojave’s western arm, the Antelope Valley. James Fremont came looking for a winter route across the Sierra with the 1844 U.S. topographical corps, and in 1845 some 250 Coast-bound settlers crossed here. In 1986 the Southern Pacific Railroad—with the help of the local Kawaiisu people, who lived in the nearby Tehachapis—put a railroad through.

Dust Devils

One of the most pervasive phenomena you’ll encounter in the Mojave is the dust devil—also called a twister, and for good reason. A dust devil resembles nothing so much as a miniature tornado.

Dust devils usually occur around noon on a calm windless day, when heated air rises swiftly and expands. Surface air moves into the vacuum to replace the rising air, and a whirl results, which gathers up sand, dust, and bits of vegetation and begins to move like a miniature tornado, made clearly visible by the debris it carries.

Antelope Valley

As the dust devil moves, it increases in height and velocity, sometimes impressively. Dust devils can (although they rarely do) reach heights of as much as a mile and can destroy parts of buildings. More commonly, and more modestly, dust devils are 10 to 50 feet tall—which is plenty big enough to wreak havoc with the tarp you’ve pitched to shelter yourself from the midday sun. On very windy days, it’s good to have a bandanna on hand and wear it bandit-style as a dust mask.

Joshua Trees

Like the giant saguaros that announce that you are in Arizona’s high Sonoran Desert, Joshua trees tells you that you are in California’s Mojave. The plant is said to have been named by Mormon settlers who thought its raised branches looked like Joshua gesturing to the Israelites. It was also called—presumably by people of less religious sentiments—a cabbage tree.

In fact, the Joshua tree is neither a tree nor a cactus (and certainly not a cabbage), but rather a yucca—in fact, a relative of the lily. Joshua trees usually grow on alluvial slopes between 2,500 and 5,000 feet in elevation, hence they are more common in the higher elevations of the Mojave. Large colonies of Joshua trees often indicate that you are approaching the transition zone between the Mojave Desert and the higher mountain ecosystems that surround it.

Joshua tree

Joshua trees can reach almost 30 feet in height and occasionally grow even higher. They are evergreen plants, able to withstand frost, drought, heat, and drying winds. The dagger-shaped dark green leaves are sharp, stiff, and leathery. In the spring growing season, a ring of new spikes encircles the tip of each live branch. Flowering varies from year to year.

Joshua trees play an important ecological role, supporting their own micro-ecosystem of plants and animals. One relationship is of particular interest, because the Joshua tree and a particular moth—the tegeticula—have a symbiotic relationship that is so codependent that without each other, neither species could survive. Like all lilies, yucca must be pollinated. Lily pollen is sticky—it is introduced by the surgical work of insects, not the random whimsy of winds. Surgical is not too strong a word. The moths are active at night and are attracted to white blossoms of the yucca. The female moth collects pollen, and when she has enough, she inserts a needlelike egg-laying organ into the “ovary” of the flower—the part of the flower that contains potential seeds. She lays her eggs and makes sure seeds will develop by depositing enough pollen. Later, her newly hatched offspring will feed on these seeds. But they will leave enough for a new generation of Joshua trees, which will in turn support many new generations of tegeticula moths.

Live Joshua trees are also home to insects; dead trees are home to termites and beetles, which process the dead wood and return nutrients to the soil. Branches provide shelter for woodpeckers, hawks, wrens, and the Scott oriole, which prefers to nest among the spikiest foliage. Other residents include yucca night lizards and wood rats. Intermittent visitors might include screech owls, red-tailed hawks, great horned owls, and rattlesnakes, all of whom regard the Joshua tree as a potential delicatessen and occasionally stop by in hope of a quick meal.

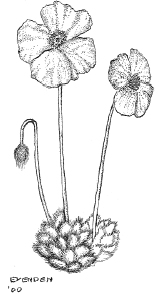

Great desert poppy

Mojave Desert Flowers

Plant life in the Mojave is very much affected by the amount and timing of the first rainfall of the growing season—not in the spring, but in autumn. Many of the annual plants germinate in late fall, when the area gets 1 or more inches of rain. Most of the annual rainfall in the Mojave comes in winter. The wildflower bloom is directly proportional to the rainfall. About once a decade, it is spectacular.

Because rain is erratic and scarce, flowering desert plants spend most of their life in a dormant state as seeds. The seeds have a hard waxy coating that protects the embryonic plant inside from drying out. A chemical in the seeds inhibits germination until enough rain leaches it away, allowing seeds to open only when there is an adequate amount of moisture. In December and January, these plants (called winter ephemerals) grow into small seedlings. Growth is slow, leaf by leaf. The young plants must endure cold nights and frost. Still, daytime temperatures are favorable—frequently between 50 and 80 degrees—and by late May, before the hot summer begins, the plants have managed to grow from seed to seed-bearer.

Desert candle

Types of flowers include brown-eyed primrose, Cholkley’s lupine, thistle sage, California poppy (long believed endemic to eastern slopes, but able to migrate here through low passes), Mojave buckwheat, desert sunflower, red mariposa lily, the desert marigold, and a memorable oddity: the desert candle or squaw cabbage. Its yellow-green stems look like the plant has swallowed some billiard balls (think of a snake that has just swallowed an animal wider than it is). To top it all off, there’s a bright tuft of purple flowers. If you add in the Joshua trees, you might well be excused for thinking of the Mojave as a place Dr. Seuss made up.

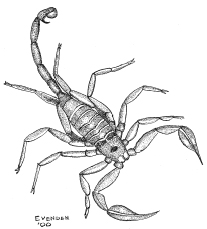

Scorpion

Wildlife

As Edward Abbey put it, virtually everything in the desert sticks, stabs, stinks, or stings. Certainly the plant kingdom lives up to this dubious reputation, and by this point in the PCT, most thru-hikers have had various prickly encounters with cactus, cholla, bayonet-sharp agave, and yucca.

But the animal kingdom, too, has its fair share of species with prickly attitudes. The Mojave is home to 10 or more species of scorpions, although you aren’t likely to see them during the day, when they hide from the heat under clumps of debris or fallen Joshua trees. Scorpions are, however, active at night (one reason that some desert hikers prefer sleeping in tents). If you camp out, check your boots in the morning, before inserting your feet!

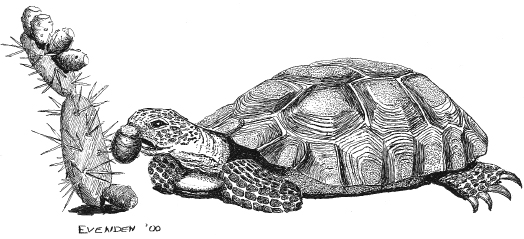

Desert tortoise

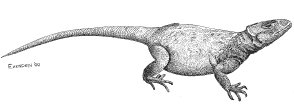

Chuckwalla

The Mojave is also home to three species of rattlesnakes: sidewinders (so called because of their winding, writhing style of locomotion), speckled rattlesnakes, and Mojave green rattlesnakes. The last is a yellow-green version of the western diamondback, only more aggressive, with a more potent venom. (For more on rattlesnakes, see chapter 1.)

Other animals you might see include the desert tortoise, although you’ll have to look closely: These big tortoises are becoming scarce, and during the day they hide in depressions under shrubs. But they are rambunctious in spring, and you may hear them snorting and banging their shells in a mating ritual.

Reptiles that inhabit the Mojave include iguanas, chuckwallas, zebratail lizards, desert-horned lizards, and collared lizards. You’ll often see the latter stopping to do push-ups. It’s not a mating ritual, as is often thought. Instead, the push-ups help the animal control its circulation and body temperature.

You’re unlikely to see coyotes in the Mojave, but you’re likely to hear them. Their canine chorus is a nightly serenade throughout the West. Nowhere is their howl more haunting than in the vast spaces of the open desert, where scarcity of game forces coyotes to cover vast distances to hunt, and therefore, to communicate with each other over long stretches of empty space. Coyotes are the best runners among the canids (a family than includes all dogs, from wolves to Chihuahuas), often cruising at 25 to 30 miles an hour, with sprints up to 40 miles an hour. In a normal night of hunting, a desert coyote pack might typically cover 15 linear miles, and sometimes much more. After dusk and before dawn, you’ll hear them barking, yapping, and howling.

Desert coyote

Antelope Valley and the Los Angeles Aqueduct

Look for signs of coyotes on rocks in sparsely vegetated areas. If it looks like a good place for a hiker to have lunch—not too many plants to trip over, a comfortable rock, and a good view—it’s a good coyote spot, too (although rather than appreciating the view, the coyotes are most likely looking for prey). Coyotes use scat and urine to mark their territories. They also dig holes—coyote wells—to get to water and then ambush prey that stop by for a drink.

Livestock Grazing

From desert tortoises, whose newly hatched young feed on foliage, to kangaroo rats that cache piles of seeds, desert animals are highly dependent on native annuals for food. Young desert tortoises, for example, depend on getting nutrition from spring wildflowers. Mice and rats depend on seeds. And carnivores depend on the success of these smaller creatures.

But the food sources—the plants and flowers—that support all this life are themselves under pressure from livestock grazing, which has had a significant impact on desert ecosystems. One flock of sheep munching its way through an area can reduce the biomass of annual plants by 60 percent. Livestock grazing also encourages the growth of nonnative species because they deposit seeds in their feces and because they do not eat many of these plants. The nonnative plants therefore have an advantage over the native plants and quickly take over. In the western Mojave, up to 70 percent of plants are now non-native species promoted by cattle and sheep. Grazers also eat shrubs, which provide shade for small animals. Fortunately new grazing restrictions were implemented by land managers in 1992 in an attempt to preserve desert tortoise habitat.

HIKING INFORMATION

HIKING INFORMATION

Seasonal Information and Gear Tips

This is a good section to avoid in the summer. Even in spring, temperatures can rise above 100 degrees. In winter, the lower elevations make for fine hiking—but it may be surprisingly cold at night. The higher elevations in winter will have some snow.

• Bring sunscreen and a wide-brimmed hat for sun protection. Some hikers additionally protect themselves with lightweight, breathable long-sleeved shirts and long pants.

• You’ll need extra water containers because the water sources are few and far between—and unreliable.

Thru-hikers’ Corner

The tiny community of Agua Dulce has in recent years become renowned in hiker circles for its friendliness. In some years, either the church or local residents have allowed hikers to camp: Ask at the post office or the Century 21 Real Estate office.

In the Mojave Desert, local resident Jack Fair provides water for hikers at his home at the PCT crossing of California Highway 138. He also offers camping and a shuttle to a nearby convenience store for a small fee.

Alternate Route

Before the compromise route that was finally established in the Tehachapis, the PCT slashed straight across the desert following the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This route was always intended to be temporary, but some hikers still take it. Two sources of information are Wilderness Press’s old PCT California guidebook (now out of print, but available in some libraries). If you can’t get your hands on the guidebook, be assured that you don’t need specific step-by-step directions to navigate through this easy, open country, especially since all you’ll be doing is following the aqueduct. A good source of information is the DeLorme Atlas and Gazetteer for California.

Here’s the route: Leave the PCT at Elizabeth Lake Canyon Road, 40 miles into this chapter’s section of trail. Descend on the road to Lake Hughes. Follow back roads past Fairmont Reservoir, then follow 170th Street west to the Los Angeles Aqueduct. Take the Los Angeles Aqueduct to near Mojave. After resupplying in Mojave, continue along the aqueduct to Jawbone Canyon. Go up into Jawbone Canyon, where the alternate route connects with the PCT 34.7 miles into the section covered in chapter 5.

The main argument in favor of the old route is that instead of a meandering, difficult up-and-down dry route through yet more chaparral, the old route introduces hikers to a completely new experience: a traverse of the Mojave Desert. Another advantage is that following the aqueduct is flat, straight, and fast. (It’s also about 30 miles shorter than the new route.) While the official route crosses California Highway 58 at a point 9.2 miles from Tehachapi and 9 miles from Mojave—requiring a hitch in either direction if you want to resupply—the old route crosses California Highway 58 within 3 miles of Mojave. Resupplying doesn’t require any hitchhiking. If you do use this route, remember to fill up with water at Cottonwood Creek because the aqueduct is sealed. There are, however, ranches and windmill farms where it may be possible to get some water.

Best Short Hikes

You won’t see a lot of short-distance and day hikers on this section. But if you’re interested in a sampling of this section’s hiking, probably the most scenic stretch is the 22.7 miles from Agua Dulce to the San Francisquito Ranger Station. Expect lots of chaparral, a rolling-up-and-down hike, and some excellent views.

Resupplies and Trailheads

Agua Dulce is the most commonly used.

Soledad Canyon (mile 0) on Soledad Canyon Road boasts several campgrounds where hikers are welcome to stay. Some of them have amenities including vending machines, swimming pools, cafés, laundry facilities, and showers. Ask when you check in if pizza delivery is available!

Agua Dulce (mile 19.7). This is one of the few towns that the PCT actually passes through. The only disadvantage: There are no hotels or campgrounds. But there is a store, and in recent years, townspeople have sometimes generously offered PCT hikers a place to stay. Post office: General Delivery, Agua Dulce, CA 91350. (The post office is in Richard’s Canyon Market.)

San Francisquito Ranger Station (mile 32.4) on San Francisquito Canyon Road. This trailhead has a reliable water supply. For resupply, you could detour 1.7 miles southwest to Green Valley.

Lake Hughes (mile 40.0) is 2.2 miles off-trail on Elizabeth Canyon Road. It has motels, showers, and limited groceries.

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press