Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press

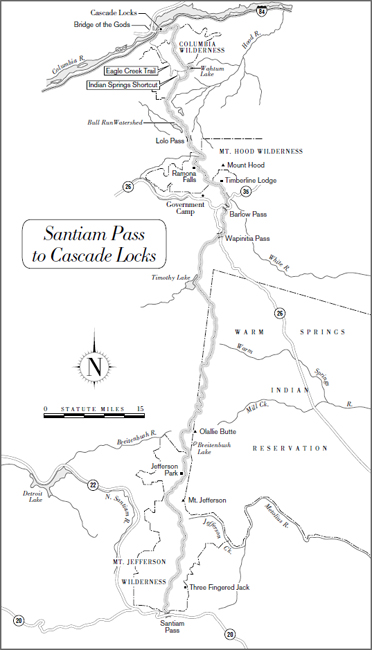

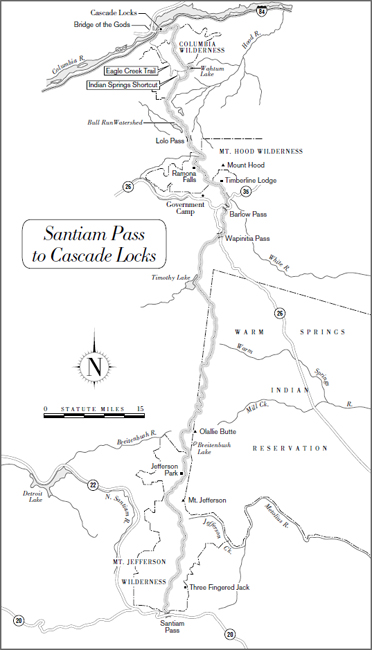

148.7 miles

On this section of trail, hikers walk on the shoulders of Oregon’s two highest peaks, then descend to the lowest point on the entire Pacific Crest Trail. Mounts Jefferson and Hood are the highlights, the first featuring beautiful subalpine parks covered with wildflowers, the second boasting excellent views of both volcanic ash and glaciers. Snow patches that linger well into the summer present an occasional obstacle on Mount Jefferson, as do fierce glacier-fed streams flowing from both mountains. The PCT passes right by the doors of historic Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood before winding its way around the mountain, past pretty (and popular) Ramona Falls, and then down into the Columbia River Gorge. For the final miles, the Eagle Creek Trail, which runs through a gorge filled with waterfalls and swimming holes, is a popular alternative to the PCT.

THE ROUTE

Leaving Santiam Pass, the PCT climbs until it is just beneath the steep wall that holds the pinnacles of Three Fingered Jack. As the trail rounds the mountain, it offers the kind of views that will have you stopping every two minutes to take yet another picture.

Descending, the route returns to forest, where there are some pleasant lakeside campsites. For the next several miles, the trail stays relatively high, often on the Cascade Divide, with good views. Entering the Mount Jefferson Wilderness, it remains high on the watershed divide.

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press

Soon, views of Mount Jefferson dominate the northern skyline. The power of the glaciers that continue to erode Mount Jefferson can clearly be seen as you cross Milk Creek, named after the amount of glacial sediment, or rock flour, it carries off the mountain. The trail crosses fast-flowing Russell Creek 4.4 miles later. This creek is unbridged, for good reason—a bridge would never survive the spring floods in this debris-studded canyon. In early season, hikers should try to cross Russell Creek as early in the day as possible, because low nighttime temperatures slow the melting of the glaciers and reduce the volume of water.

The trail then winds through the lovely upland meadows of unfortunately overused Jefferson Park. Although the campsites are picturesque, two things might chase you away: too much company of the two-footed kind—and too much company of the six-footed kind. The latter are ubiquitous right after the snowmelt, sometime in mid to late July.

North of Jefferson Park, late-lying snowfields can complicate travel because snow often lingers well into August. Some patches survive the entire summer.

The trail then enters the Mount Hood National Forest, where it makes its way through lake-dotted country to Olallie Lake, at the base of the symmetrical cone of Olallie Butte. North of the butte, the land becomes abruptly dry and the trail enters the backcountry of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. For the next 20 miles, the trail is fairly flat, forested, and easy. It leaves the reservation near Clackamas Lake. There’s a temporary surplus of water as the trail circles around Timothy Lake. But then it climbs a ridge and becomes dry again.

Mount Hood is only occasionally visible from the PCT. The first unrestricted close-up views are just north of the PCT’s crossing of U.S. Highway 26 at Wapinitia Pass, a few miles past Timothy Lake. Then the views almost entirely disappear, blocked by thick forest. A few miles farther, the trail crosses Oregon Highway 35 at Barlow Pass, an important gateway for 19th-century immigrants. Now the trail climbs steadily until it is above treeline on the shoulder of Mount Hood.

And suddenly, you rise above the forest, and the views to the summit are breathtaking. Look closely at the tiny moving dots high up on the mountain slopes. You aren’t seeing things: Those really are skiers, who take to the slopes almost year-round.

From Mount Hood, the trail circumambulates the west side of Mount Hood. (Note: There is an around-the-mountain trail that makes a loop encircling the whole peak.) It crosses a series of glacier-fed streams. Some of these can be tricky to negotiate during the snowmelt. Views up to Mount Hood’s summit more than compensate for any difficulties.

The trail passes a turnoff for Paradise Park shelter. The dramatic views of scoured canyons and shimmering glaciers continue. Shortly after crossing the Sandy River (which has been recently bridged) the trail passes lovely Ramona Falls, a popular destination for day hikers who access it using a series of Forest Service back roads and trails. There’s no camping within 500 feet of the falls, but it’s a great place for a lunch stop.

Continuing on, the trail crosses Lolo Pass and climbs to a ridgeline. Seven and a half miles north of the pass, hikers can take a 0.5-mile side trail to the summit of Buck Peak, where unrestricted views extend south to Mounts Hood and Jefferson and north to Mounts Adams, St. Helens, and Rainier—the first time PCT hikers can see all five of these peaks at once.

After Buck Peak, the trail continues on a ridge to the Indian Springs campsite. A few miles later, it reaches Wahtum Lake, from which it begins a long gentle descent to the Columbia River Gorge.

Alternate Route

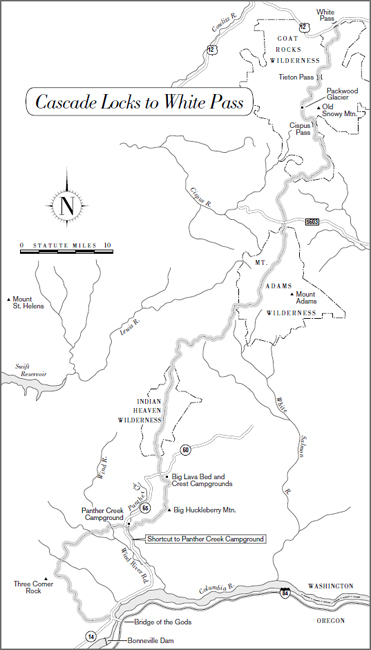

Most hikers do not take the Pacific Crest Trail into Cascade Locks, the last town in Oregon. Instead, they detour to the Eagle Creek Trail. The Eagle Creek Trail was not chosen to be part of the PCT’s official route because it is impassable for horses. But the majority of thru-hikers reach the sensible conclusion that they are not horses, and therefore there is no reason to miss one of Oregon’s most deservedly popular trails.

The Eagle Creek Trail can be accessed from one of two points. The shortest way (a 2-mile descent) is to take Indian Springs Trail 445 from the Indian Springs Campground. Steep and muddy, on a wet day this trail is almost slick enough to just sit and slide. A gentler but longer option is to continue on the PCT until the junction with the Eagle Creek Trail at Wahtum Lake. This choice is more pleasant and definitely easier—but it’s also 3 miles longer than the Indian Springs shortcut.

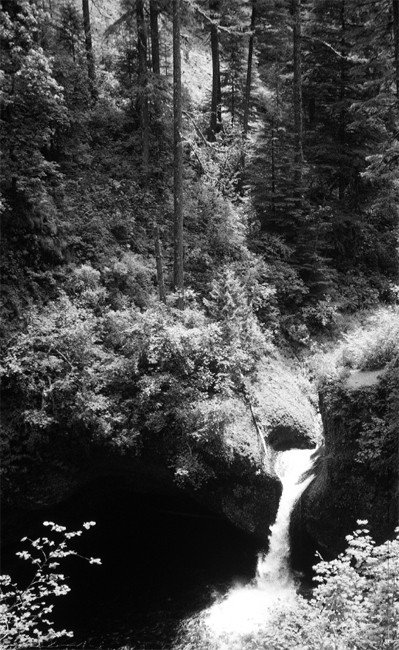

Eagle Creek is a deep-cut gorge that feeds into the Columbia River. The Eagle Creek Trail parallels it, passing numerous campsites dotted along the river edge. It’s a very popular trail with day hikers and weekenders, but the campsites farther upstream are out-of-reach for most casual weekenders, so they tend to be less used, cleaner, and more attractive. Continuing downstream, the trail passes pools and cascades, and even goes behind a waterfall on trail that was blasted into the rock. Once at the Eagle Creek trailhead, hikers must follow Gorge Trail 400 for 2.6 miles to reconnect with the PCT at Moody Avenue on the outskirts of Cascade Locks. If you’re going to the campground at Cascade Locks City Park, you should leave the Gorge Trail after 0.7 miles and take the bike path instead—it’s quicker and more direct.

Along the Eagle Creek Trail

WHAT YOU’LL SEE

Three Fingered Jack

Three Fingered Jack is the last of Oregon’s Matterhorn peaks. Like the others, it too was once a shield volcano that has been severely eroded by glaciers. Its central plug has survived, surrounded by spires—or fingers. The mountain has a different profile when viewed from different directions; all of the fingers are visible only from the southeast.

If you’re a rock climber, you might enjoy spending a day here. Three Fingered Jack is very steep—even the snowfields at its base are at 50- degree angles—and it attracts hordes of climbers. The easiest route is up the South Ridge from Square Lake, which involves an ascent of 5 to 7 hours to the 7,841-foot summit.

Mount Jefferson

Lewis and Clark were the first European Americans to see Mount Jefferson when they stood near the mouth of the Willamette River on March 30, 1806. They promptly named the mountain for their benefactor. In later years there would be an attempt to name or rename the major peaks of the Cascadian chain after other American presidents, but only Mount Washington (a paltry 7,802 feet, which the PCT passed in chapter 13) and Mount Adams (in Washington, north of the Columbia River Gorge) were so named.

At 10,495 feet, Mount Jefferson starts to dominate the landscape about 5 miles north of Three Fingered Jack. Sitting on a ridge that averages 5,500 to 6,500 feet above sea level, it rises more than a mile above the surrounding landscape. Oregon’s second-highest peak is also one of its most photogenic, with five glaciers, including one—the Whitewater Glacier on its eastern side—that actually dips below tree line. Geologists estimate that Mount Jefferson’s original elevation might have been as high as 12,000 feet, but that it has been cut down by glaciation, and its summit has been sharpened to a point. Like most of the other major Cascadian peaks, Mount Jefferson is a stratovolcano. It may be extinct.

Mount Jefferson

The summit of Mount Jefferson is surrounded by wilderness on one side and the Warm Springs Indian Reservation on the other, so it is not readily accessible to climbers. The best route to the summit is via the Whitewater Glacier from the lakes in Jefferson Park. The climb is considered the most difficult of Oregon’s volcanoes; the round trip takes about 8 to 10 hours.

Jefferson Park

Clinton Clarke described Jefferson Park as “unexcelled in the Pacific Northwest as a natural alpine garden sprinkled with lakes and streams, above which rises graceful, glacier-hung Mount Jefferson. The alpine region is a fascinating land of picturesque and friendly beauty. A paradise for camper and nature lover.”

Jefferson Park is the first of the many alpine parks—natural alpine gardens—that are found along the PCT from here to Canada. Alpine gardens are ecotones between subalpine forest and alpine meadow. Here in Oregon, they occupy elevations ranging from 5,500 to 6,000 feet. The higher the elevation, the fewer the trees. These parks are in the Hudsonian zone, which thru-hikers first encountered 1,839 trail-miles south, when the trail briefly topped 9,000 feet in the San Jacinto Mountains. If you’re a thru-hiker—or if you’ve previously hiked in southern California’s mountains—you’ll notice some significant differences in the character of the two Hudsonian zones. In southern California, the Hudsonian zone occupied the very pinnacles of only the highest mountains on steep slopes exposed to high winds. Here, the Hudsonian zone is found far lower on the mountain; the rock, ice, and glaciers of Mount Jefferson tower almost a vertical mile above. Instead of windswept ridges, the alpine parks occupy relatively flat meadows on which water from a deep, late-lying snowpack promotes the growth of grasses and flowers. In the weeks just after snowmelt, Mount Jefferson’s alpine garden is a riot of color, made even more beautiful by the many lakes and ponds that reflect the snowy profile of the peak above.

Warm Springs Indian Reservation

After leaving the Mount Jefferson Wilderness and passing the Olallie Lake Ranger Station, the trail enters the Warm Springs Indian Reservation for 22 miles between Jude Lake and Clackamas Lake. This section was the subject of a long-standing land ownership debate between the Warm Springs Indian Confederation and the Forest Service. The disagreement dates back to two conflicting 19th-century surveys. The disputed area, called the McQuinn Strip after one of the surveyors, was also the corridor for the Pacific Crest Trail. In 1972 the matter was settled by Congress, which agreed with the Indians and transferred the strip from the Forest Service to the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Special wording in the federal legislation provides for use of the strip by the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail.

Barlow Pass and Road

As beneficiaries of cut trails and engineered Forest Service roads, hikers do not usually perceive Oregon’s terrain to be unduly difficult—quite the contrary. But a century and a half ago, pioneers crossing the Cascades to the Willamette Valley would have had quite a different tale to tell. In the 1840s, crossing the Cascades meant attempting to following the Columbia River—a difficult task because of the many cataracts. Or it meant hoisting wagons up and down steep slopes by ropes and cables. Even today, scars from the cables and bits and pieces of old cable can still be found on the trees south of Mount Hood. A route over the Cascades was desperately needed.

Samuel K. Barlow was a wagonmaster looking for ways to get wagon trains to the Willamette Valley. In 1845, a partner of Barlow’s named Joel Palmer climbed the upper slopes of Mount Hood and spotted the pass. In 1846, a road through the pass was opened.

Mount Hood

At 11,235 feet, Mount Hood is the highest peak in Oregon. Because it is located on one of the lowest points on the Cascade Crest, it looks even taller, and dominates the Portland region much as Mount Rainier to the north dominates Puget Sound. Planes flying into Portland from the east pass right by the north side of Mount Hood; try to get a seat on the left to see one of the best airborne views to be had from any plane going anywhere. Earlier travelers to the Portland area also appreciated their view of the mountain, which told them that their long and arduous journey was almost over.

Unlike Mount Jefferson, 50 miles to the south, nobody thinks Mount Hood is extinct. Mount Hood was active in the 19th century, and in 1973 shot a plume of vapor 1,500 feet into the air. The mountain frequently discharges vapors and smoke, sulfur odors, fumaroles, gas vents, and steam jets, and on its flanks a literally boiling-hot spring furiously bubbles. It is not unusual for steam and sulfurous fumes to escape from Crater Rock and form ominous-looking clouds above the summit.

Because the PCT’s route just south of Mount Hood is forested, you don’t get a good look at the mountain until you are very close to it. John Muir was (not uncharacteristically) moved by his first sighting. In Steep Trails he wrote,

There stood Mount Hood in all the Glory of the Alpenglow, looming immensely high, beaming with intelligence, and so impressive that one was overawed as if suddenly brought before some superior being newly arrived from the sky. The whole mountain appeared as one glorious manifestation of divine power, enthusiastic and benevolent, glowing like a countenance with ineffable repose and beauty, before which we could only gaze in devout and lowly admiration.

Mount Hood’s construction is unusual for a major volcanic peak because it is made mostly of pyroclastic material with very little solidified lava (unlike other major stratovolcanoes, which have more lava and infrequent layers of pyroclastic matter). The PCT crosses one of Mount Hood’s dominant features: a huge debris fan on the southwest slope, which was produced some 1,700 to 2,000 years ago by the eruption of a single plug dome. The explosion melted ice fields and produced mudflows, which created the debris fan. The prominent crater rock above the fan is what is left of the plug dome, and the pools of boiling water around the rock are evidence of the mountain’s ongoing geothermal activity. Other volcanic features include a 500-foot-thick, 8-mile-long lava flow, and piles of ash that PCT hikers must struggle to walk through. The mountain boasts 11 glaciers, which are responsible for eroding the peak from its original height of around 12,000 feet.

Indian Myths

Not having taken Geology 101, the Indians who lived in the area had other explanations for the behavior of Mount Hood, which they called Wy’east.

Wy’east was once so tall that when the sun shone on its south side it produced a shadow that was “a day’s journey long.” Evil spirits lived inside the mountain, and they routinely threw fire down on Indian homes. One day a brave decided to challenge the spirits and stop their persecution of his people. So he climbed up and threw rocks into the holes where the spirits lived. The spirits threw back hot rocks that rained on the village below and destroyed it. In grief the brave sank into the earth and was buried by lava. You can see his profile today, at the Chief’s Face rock formation on the north side of the mountain.

Recreation on Hood

After Japan’s Fujiyama, Mount Hood is the most often climbed snowcapped mountain in the world, and is regarded as an easy climb. As on so many other accessible peaks, you may hear the apocryphal story of a woman tottering to the summit in high-heeled shoes. The high-heeled lady may be merely a myth, but in 1867, the first woman to stand atop Mount Hood did reach the summit wearing a skirt. And in 1894, 193 people (including 38 women) climbed Mount Hood and founded the Mazamas, the first mountaineering club in the Pacific Northwest. Warning: Despite its popularity (and notwithstanding the business about skirts and high heels), Mount Hood is a serious climb. Don’t attempt it without a guide unless you have mountaineering experience. Crampons, ice axes, rope, and an avalanche beacon are required, along with serious cold-weather gear. You must have a climbing permit. Most climbers start at midnight in order to climb on firm snow and reach the summit before sunrise—warm daytime temperatures create serious avalanche hazards. Prime climbing season is May through mid-July. The southern slopes are especially prone to rock-fall after the snow starts to melt in the beginning of July.

If skiing is your passion, you can also take a day off at Timberline Lodge. The ski area is open an average of 345 days a year. Lifts operate throughout the summer, whenever there is snow.

Timberline Lodge

Perched on Mount Hood near timberline at an elevation of 6,000 feet, Timberline Lodge is one of the finest example of so-called parkitechture, a rustic building design that makes use of natural materials and Indian and Western decorative themes. A Works Progress Administration (WPA) project, the structure was built during the heart of the Great Depression by unemployed craftspeople, who were given a chance not only to work, but to create something beautiful with their skills. The lodge was built entirely by hand of timber and stone, sometimes under difficult conditions. The site was surveyed in spring of 1936 when 14 feet of snow remained on the ground. Workers lived in tent cities, were trucked up the mountain, and sometimes had to warm their hands on portable stoves in order to keep going. The lodge was named a National Historic Landmark in 1978. Carefully restored and maintained, it has become a center for craftsmanship in the Pacific Northwest.

Bull Run Watershed

North of Lolo Pass, more land-use litigation briefly impacted the Pacific Crest Trail. The PCT runs along the boundary of the Bull Run management area, which is the watershed for the Portland region. As in the case of the land on the Warm Springs Indian Reservation, the initial dispute had nothing to do with the PCT.

In 1973 an environmental coalition sued the Mount Hood National Forest to prevent logging in the Bull Run preserve. The law they relied on was the 1904 Bull Run Trespass Act. In 1976 a federal judge agreed with the environmentalists—but in a narrow reading of the law, he closed all the trails in the area, saying that the law precluded recreational use as well. In 1977 Congress passed the Bull Run Watershed Management Act, which changed the area boundaries so that the trail is now outside the official watershed. You’ll see the property boundary signs as you hike along, warning you to stay out.

HIKING INFORMATION

HIKING INFORMATION

Seasonal Information and Gear Tips

Like the rest of Oregon, the best hiking season is August and September; August is more crowded. Parts of this section can be impassable well into July, especially in Jefferson Park, where snowfields typically don’t melt until late summer. The ford of Russell Creek can also be dangerous in early season. In most years, the hiking season extends into October, although the weather is less predictable and both snow and freezing temperatures are possible at the higher elevations.

• Early-season hikers should take an ice ax, compass, and topo maps.

• July hikers need a tent and plenty of mosquito repellent.

• All hikers need rain gear.

Thru-hikers’ Corner

Most northbound thru-hikers will come through this section of Oregon in peak season, usually sometime in August. There are no especial considerations: The hiking is easy and fast, the views superb. Enjoy it!

Southbounders may arrive in mid to late July, depending on their starting date. If you arrive early, or if the snowpack is especially high, you should carry an ice ax through the Mount Jefferson Wilderness. But what lies ahead is not as difficult as what lies behind: If you’ve had a relatively easy run through Washington, you can probably send home your ice ax.

Best Short Hikes

• From Santiam Pass on Highway 20, head north to Three Fingered Jack. This 14-mile (round trip) day hike takes you to fabulous views just below the jutting pinnacles. Unless you’re a technical climber, though, you’ll have to be content with admiring the summit from afar. The climb is for rock climbers only.

• Hike into Mount Jefferson Wilderness and Jefferson Park. The most direct entry is to park on Skyline Road 42 and hike south on the PCT; 7.6 miles (and a 1,500-foot elevation gain) takes you into the heart of Jefferson Park, where there are many side trails to lakes.

• From Timberline Lodge to Paradise Park is 4.5 miles (one way). There is an old, poorly maintained shelter at Paradise Park. This makes for a good out-and-back day hike, but if you’ve got a little extra time, you might want to bring your backpacking gear. Leave off your load at the shelter and take some time to explore a little farther before returning to camp for the night. The views in and out of Mount Hood’s many canyons are spectacular.

• If you are more ambitious, a full loop of Mount Hood (16.2 miles on the PCT plus 22.7 miles on Timberline Trail 600) typically takes 3 to 4 days.

• Santiam Pass Loop, approximately 50 miles long, takes advantage of the old Oregon Skyline Trail. Start at Santiam Pass. After hiking 2.4 miles north, take Trail 3491 (Santiam Lakes Trail) 4 miles to Santiam Lake. Go 0.6 miles farther, then take Trail 3494 north for 2.5 miles. At Jorn Lake, take Trail 3492 east for 3.4 miles. Then take Trail 3437 for 2 miles to Marion Lake. Next up is Trail 3493 for 5.3 miles. After teeny Papoose Lake, the trail reaches a juntion. Going south shortens the hike by about 10 miles—you’ll hit the PCT in 2 miles, from which it is about 20 miles back to Santiam Pass. If you continue north, past Pamela Lake, you’ll also rejoin the PCT, but your hike will be 50 miles long instead of 40. This old Skyline Trail segment passes many lakes and campsites. Note: If there is heavy snow, this route offers a lower and less snowy alternate for early-season hikers (or for hikers struggling through the white stuff in midsummer after an especially snowy winter).

Resupplies and Trailheads

Timberline Lodge is the most commonly used.

Olallie Lake Resort (mile 46.2) is an unreliable resupply. Rangers are doing their best to help hikers, but the fact is that many packages sent here never get to the hikers—even those who use guaranteed mail delivery services. Here’s the deal: You mail your package to the address listed below, and the rangers bring it to the resort, which holds it for hikers. Send your package several weeks in advance, because the rangers sometimes don’t come around for a while. Also understand that after a severe winter, the roads may not be open—even in late July or early August. If your package doesn’t get there, the resort store does sell enough food to get you to Timberline Lodge. They also offer cabins, showers, and tent sites. Send packages to: Olallie Lake Resort, c/o Clackamas Ranger District, 595 NW Industrial Way, Estacada, OR 97023.

Timberline Lodge (mile 100.4) on the shoulder of Mount Hood is an attractive rest stop, and it’s right on the trail. Facilities include laundry (for lodge guests only) and a fine restaurant. There’s also cheaper grub in the main ski building where you’ll find the Wy’east Store, which holds hiker boxes. Don’t expect to be able to buy provisions here: The store caters to the tourist crowd. You can’t eat a T-shirt, so mail yourself everything you’ll need to get to Cascade Locks. The lodge has several bunk rooms available for groups of different sizes. To send a resupply box, contact: Wy’east Store, Timberline Lodge, OR 97028.

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press