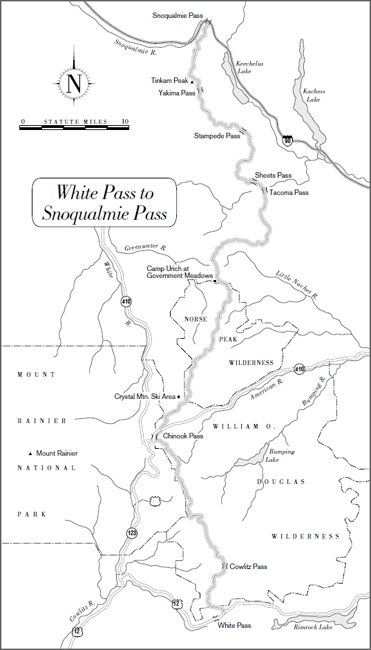

Bridge of the Gods

147.7 miles

The PCT’s route in Washington follows much of the original route of the Cascade Crest Trail, built by the Forest Service in the period 1935–39. The 531-mile Cascade Crest Trail (today’s Washington PCT is 558 miles) was built to connect with the Oregon Skyline Trail. Since most of the original Oregon Sky-line Trail is now abandoned, those parts of the Cascade Crest Trail that are still in use are the oldest miles on the PCT. Occasionally you’ll see a weather-beaten sign that tells you you’re on the Cascade Crest.

Formed by volcanic activity, glaciation, and plate tectonics, this section contains a great deal of variety. As in Oregon, southern Washington’s PCT follows the line of great stratovolcanoes—Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Rainier—that, each in turn, rise a vertical mile or more above the surrounding mountains.

In the far south, the trail follows a series of ridges separated by steep, deep valleys. Between the ridges, the trail passes through lake-dotted woodlands. The views become more and more dramatic as the trail approaches Mount Adams, where you’ll see extensive regions of lava flows, volcanic ash, pumice fields, and enormous mudflows. The section ends with a glorious traverse of the rock-and-ice landscape of the Goat Rocks Wilderness, one of the PCT’s finest high-country rambles.

THE ROUTE

This section begins at the town of Cascade Locks on the Oregon side of the Columbia River. The trail crosses the river on the Bridge of the Gods, then, on the Washington side, reaches the lowest point (140 feet) on the entire PCT.

The first 35 miles of the section are often criticized, mostly because they involve an indirect route that gains then loses some 5,000 feet of elevation. For thru-hikers in a hurry, there’s a direct option—a road walk up Washington Highway 14 and the Wind River Road—that is only 14.7 miles long with only a few hundred feet of elevation gain.

The official PCT route is a little on the bland side, although it does offer some good views of Mounts Hood, Adams, St. Helens, and even Rainier. Its meandering path from the Columbia River to Panther Creek Campground was largely dictated by private land considerations, so it doesn’t especially make good foot-sense. Because water can be in scarce supply, you should carry extra. Similarly, there aren’t many good campsites, so you may need to use a little ingenuity when deciding where to make your home for the night. Some short-term hikers with limited time in Washington might want to maximize the scenic quality of their hike by skipping these first 35 miles and starting instead at Panther Creek Campground.

From Panther Creek Campground, the trail follows a series of ridges. In good weather, be sure to take the 0.2-mile side trip up Big Huckleberry Mountain. The trail is usually overgrown with huckleberry bushes, but the views from the summit of all the major volcanoes is unparalleled. Warning: Until recently, the 15 miles between Panther Creek and Crest Campgrounds had few reliable water sources (and Crest Campground itself has no water source). But several new side trails to springs have recently been built, along with a water catchment just before Crest Campground. The guidebook does not include information about some of these sources of water, so check with the PCTA for up-to-date seasonal information.

Continuing north, the trail winds through the lake-dotted Indian Heaven Wilderness, then goes through the Sawtooth Huckleberry Fields where in August and September you’re likely to be delayed by the tempting purple berries. The trail then undulates a bit before climbing for real into the Mount Adams Wilderness for a perambulation around the western flank of Mount Adams. The trail stays at about the 6,000-foot level, below the summer snow-line on the mountain’s shoulder but high enough to offer excellent views in good weather. This area is especially popular with horse riders. Expect crowds on weekends, especially at popular campsites like Killen Creek, from which there is an excellent view of Mount Adams. Warning: Some of the stream crossings of glacier-fed creeks that drain Mount Adams can be tricky in early season.

While there’s no shortage of water on this stretch, plan a rest stop at Lava Spring, about 5 miles north of Killen Creek on the north side of Mount Adams. Some hikers claim that this trailside spring has the best-tasting water on the entire PCT. It’s worth a stop, even if your water bottles are full.

Between the Mount Adams Wilderness and the Goat Rocks Wilderness the trail stays below the tree line, passing a series of stagnant ponds that, even in August, provide breeding grounds for an unimaginable number of mosquitoes. If you’re here in bug season, be prepared for plenty of buzzing, biting company, which you finally escape by climbing into the high country of the Goat Rocks Wilderness, the only true stretch of trail in southern Washington that is above tree line. Because of unpredictable weather, high winds, and long exposed stretches of trail, hikers need to use caution here. Be sure you have extra layers of clothes, and keep an eye on the weather.

Note: Both the guidebook and the data book make reference to the Dana May Yelverton Shelter, which was built after a hiker by that name died of exposure in the Goat Rocks. The shelter is gone. All that is left is a pile of rocks that might provide a slight windbreak in an emergency, if that. There are, however, excellent high-country campsites in the area if the weather is good.

North of the shelter site, the trail splits, and you have a choice of going across the upper slopes of the Packwood Glacier or taking an even higher route that leads up over the shoulder of Old Snowy Mountain. The glacier slopes are not steep, but they can be slick, especially after freezing rain. If you don’t have an ice ax and you don’t like the feel of the snow underfoot, taking the high route is an option, especially in good weather. The trail is boulder strewn, with a jumble of cairns pointing the way—and sometimes, confusingly, they point several ways, but they all lead to the same place. Once you reach the high shoulder of Old Snowy, you reconnect with the PCT by simply continuing along the ridge over Packwood Glacier, then climbing back down on slippery scree to rejoin the PCT. On a blue-sky day, take the 300-foot detour from the trail’s high point on the shoulder of Old Snowy to its 7,930-foot summit. The views are worth the effort, not to mention that, unless you go in for some serious peak-bagging, this will probably be your highest point in Washington. Be sure to sign the summit register.

Whichever way you go, the trails merge just south of a formation called Egg Butte, on a ridge that William O. Douglas described in his book Man and Wilderness: “This trail is only a few feet wide, the drop-off on each side is so great that some people get vertigo. It is indeed a bit like walking the cornice of the Empire State Building.” Keep an eye out for mountain goats here. This is exactly the kind of precipitous terrain they consider ideal for a casual stroll.

Warning: From the Yelverton Shelter site, there is no water and no opportunity to camp for about 6 miles. The first obvious campsite, in a basin just north of the junction with Coyote Trail 79, is very exposed. In bad weather, you’ll want to try to plan your day so that you have enough time to descend another few miles to tree cover and water. Many hikers familiar with this section are convinced that the mileage cited in the guidebook and data book for the distance between Yelverton Shelter and White Pass is too short: These 18 miles seem more like 20. So plan conservatively.

The trail climbs once more to traverse two wide, exposed bowls, where there’s another good chance of seeing mountain goats. There are a couple of campsites up here, but you’ll need to carry water. Leaving the Goat Rocks Wilderness, you’ll pass some side trails leading to ski slopes. From here, it’s all downhill. The trail makes an easy switchbacking descent to White Pass (where long-distance hikers resupply). Going straight down the ski slopes is more direct—and a sensible choice in mosquito season, as there are fewer mosquitoes in the ski-slope clear-cuts than in the forest.

WHAT YOU’LL SEE

Washington Weather

They say you can predict the weather by Mount Rainier. When you can see the mountain, it is going to rain. When you cannot see it, it is raining.

Washington weather is infamous for good reason. Heavy precipitation is one of the dominant characteristics of the Cascade Crest in Washington. It’s one reason why the old-growth forests are so rich. Running parallel to the Pacific Ocean on a north-south axis, the Cascades act very much like the mountains of southern California: They wring rain and snow out of the moisture-laden air as it moves east. As the air rises, it turns to rain or snow. The difference here is the amount of rain and snow. The Pacific air in the Northwest contains much more moisture than the air in southern California, and the mountains are much higher. In some years, more than 700 inches of snow can fall on Mount Rainier!

Fortunately for hikers, the dry season falls during the summer (usually August and early September). However, if you’re caught in four or more days of needle-sharp rain, you might wonder about the definition of dry season. Nonetheless, Washington’s PCT offers some of the best hiking to be found anywhere. Bring rain gear—and a smile.

Columbia River

The Columbia River is the only major drainage that cuts through the entire 700-mile-long Cascade Range. The river is actually older than the mountains. As the mountains were uplifted as a result of tectonic activity, the river was able to hold its own because its rate of erosion was greater than the mountain range’s rate of growth.

As the only natural waterway through the Cascade Mountains, the Columbia has always been an important transportation artery. It was first seen by Europeans when British explorer Robert Gray sailed by its mouth in 1792. In 1805, Lewis and Clark used it to make their way to the Pacific. They named the nearby mountains the Mountains by the Cascades because of the many cascades they passed. Later settlers—who also used the Columbia to reach the Pacific Coast—shortened the name, and the entire mountain range became simply (and appropriately) the Cascades.

Bridge of the Gods

Just after crossing into Washington on the Bridge of the Gods, the PCT reaches the lowest point on its entire three-state journey, 140 feet above sea level.

There are a number of Indian myths associated with this area, most of which concern the behavior and relationships of the giant volcanoes. The stories differ in the details, but follow the same common plot, usually involving some combination of combative suitors, flirtatious maidens, and conflicts with cataclysmic results.

Bridge of the Gods

According to one version of the legend, the Bridge of the Gods was a stone bridge built by the great spirit Manitou. Manitou made the wise old woman Loo-wit the guardian of the bridge, and sent his sons Wy’east (Mount Hood) and Klickitat (Mount Adams) to help her. But the two sons soon began fighting over the attention of lovely Squaw Mountain, who also lived in the neighborhood. Squaw loved Wy’east, but couldn’t resist flirting with Klickitat. The two suitors responded predictably: They hurled stones at each other across the river until they managed to destroy the bridge. Klickitat, the bigger mountain, won the battle and the lovely Squaw. But his affections went unrequited, and Squaw Mountain fell asleep forever. The old woman was rewarded for her efforts by Manitou and was turned into Mount St. Helens, the most beautiful mountain in the world.

The legend of the Bridge of the Gods has its origins in landslides along the Columbia River. Scientists say that 29,000 years ago there was indeed a land bridge across the Columbia. The bridge was created when a mountain on the Oregon side collapsed and blocked the river, damming it and creating an inland sea as far east as Idaho. Eventually, soft matter beneath the dam eroded, allowing water to pass underneath the rocks and ultimately wash away the dam.

You’ll see evidence of landslides in the first 10 miles of Washington’s PCT, which climbs 2,000 feet onto a ridge of Table Mountain. The footway is uncharacteristically steep and rubbly because of the debris from periodic earth slides that occur along the Columbia. These landslides are simply the result of gravity. The lower layer of the earth is clay, which is prone to collapse and slide. On top of this clay is more durable matter. When the clay finally succumbs to gravity and crumbles under the weight resting on it, it slides down into the Columbia River Gorge.

The actual bridge hikers walk across was built in 1926 and raised in 1933. The stones that figure in the Indian legend are underwater just upstream.

Big Lava Bed

About a mile before reaching Crest Campground on Forest Road 60, the PCT goes through the so-called Big Lava Bed, a 20-square-mile lava flow that erupted 8,200 years ago. The rocks here are very dark, made of basalt (a dark and fine-grained igneous rock that originated as molten magma in the earth’s mantle, was spewed out of a vent, and then solidified). You will see dramatic jumbles of fractured lava, broken into blocks, chunks, and weird-shaped formations. The source of all this is a vent near Goose Lake, several miles east of the PCT. Except for a short stretch of PCT, no trails (let alone roads) cross the lava bed. The presence of this porous volcanic rock explains the paucity of water in this section. A few hardy pine trees are slowly attempting to colonize the area.

Indian Heaven Wilderness

The Indian Heaven Wilderness begins on the north side of Forest Road 60 just past Crest Campground. This area, geologically related to the Big Lava Bed as part of the Indian Heaven Rift, shows evidence of extensive volcanic activity that lasted for hundreds of thousands of years. It contains 45 volcanic vents similar to the vent that produced the Big Lava Bed, several extinct volcanoes, and numerous craters—some of which have become lakes. The trail passes several prominent volcanic features, including Gifford Peak, the oldest volcano in the Indian Heaven Wilderness, which you’ll see rising above Blue Lake. Gifford Peak was created some 730,000 years ago when several vents exploded, laying down a strata of lava. Continuing eruptions ended up building the cinder cones now known as Gifford Peak and Berry Mountain, which the PCT climbs. Farther north and just off the PCT is 5,323-foot Sawtooth Mountain, a shield volcano that erupted and spread basalt over the surrounding area some 300,000 years ago. It is the most conspicuous feature on the north end of the Indian Heaven Wilderness.

A rich land of abundant wildlife, berries, and fish, the Indian Heaven Wilderness has been used by Indian tribes for more than 10,000 years. One of its intriguing features is the Race Track, which lies about half a mile off the PCT on Trail 171A. During the annual berry harvest, Indians would race horses on this level meadow. More than 100 years later, the indentations they left behind are still clearly visible.

You might see evidence of other traditional Native American activity if you look closely at western red cedars for scars of peeled bark. These so-called basket trees were used by Indians to make baskets. On one tree, the scars can be dated to 1769.

Beargrass

Another more recent crop is beargrass, which is sold to florists for use in flower arrangements. Beargrass-picking is hard work, requiring tough gloves and a strong back. But the demand for the decorative greenery is high, and you may well run into beargrass pickers along the trail. In recent years, Asian immigrants have joined Native Americans in this occupation. Permits are required.

Sawtooth Huckleberry Fields

The Indians may not be racing horses in the Indian Heaven Wilderness anymore but they still harvest huckleberries.

There’s no shortage of huckleberries anywhere along Washington’s PCT, but the Sawtooth Huckleberry Fields just north of the Indian Heaven Wilderness are especially rich. Native Americans cyclically used fire to clear vegetation and maintain the vigor of the berry fields. For miles, the huckleberry bushes tempt late-August and September hikers to slow down and snack.

For generations many Pacific Northwest tribes, some from as far away as what is now Montana, gathered here in late summer for an annual huckleberry feast. They would harvest and dry berries, have horse races and competitive games, dry meat, tan hides, and fish.

Huckleberries

In 1932, ownership of the Sawtooth Huckleberry Fields became an issue when non-Natives began to harvest the berries. The Yakima Tribe and the Forest Service signed an agreement that reserved the berry fields east of Forest Road 24 for the Indians. The western side of the road (through which the PCT passes) is open to all pickers, although commercial pickers must have a permit.

Mount Adams

William O. Douglas wrote:

I may not see it for hours on end as I travel this mountain area, for the trail is usually beneath a ridge. Yet when I travel there I almost feel the presence of the mountain. I am filled with the expectancy of seeing it from every height of land, at every opening of a canyon. And the sight of its black basalt cliffs crowned with white snow, both set against a blue sky, is enough to make a man stop in wonderment.

Douglas’s experience notwithstanding, PCT hikers usually have excellent views of Mount Adams, which dominates most of the trail in southern Oregon. From about the Sawtooth berry fields northward, the PCT offers so many good views of Mount Adams that you may well return home with several rolls of film showing the same white-topped peak.

At 12,276 feet, Mount Adams is the second-tallest mountain in Washington, a massive stratovolcano covering an area of 48 square miles. A squat-shaped mountain with a flat summit, Mount Adams is actually composed of several superimposed cones leaning on top of each other.

Mount Adams

Geologist Stephen Harris describes Adams as “old, weather beaten and asymmetrical,” and perhaps this is what led to the Indian legends portraying Adams (or Klickitat) as a beaten-down, tired old warrior (see page 254).

Certainly, it is ancient. The first eruptions in the area can be dated to almost a million years ago. Major eruptions that occurred about a half-million years ago formed a volcano about 3 miles south of the present summit; later eruptions moved the focus of activity north to the present summit, which began building about 460,000 years ago. The last eruptions on the summit are thought to have taken place about 10,000 years ago (although some geologists place the date at between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago). But the entire area is geothermally active, and certainly many younger parasitic cinder cones around the mountain’s base have erupted as recently as 2,000 to 4,000 years ago.

You’ll see lava from one of the more recent explosions above Lava Spring, just off the trail, where a 7-mile-long lava flow cut into the Muddy Fork drainage between 3,500 and 6,800 years ago. Two miles farther, the PCT passes a much older volcanic feature, 5,387-foot Potato Hill, a cinder cone that was created after a vent erupted 120,000 years ago. A cross-country ascent of 600 feet brings you to the summit, where you can see the shallow remains of the crater that once ejected so much lava that it filled the valley to the north to a depth of 90 feet.

Mount Adams is heavily eroded by glaciation, especially on the east side of the mountain, where the Klickitat Glacier has carved the second-largest cirque and amphitheater in the Cascades (the largest is on Mount Rainier). However, since Mount Adams lies much farther to the dry eastern side of the range than the other major Cascadian peaks, all of its glaciers occur above 6,500 feet. The PCT circles it at a reasonably level elevation of about 6,000 feet, well below the summer snow-line.

Mount Adams was first climbed in 1845 by three members of a work party that was building a military road through Naches Pass to connect the Columbia River with Puget Sound. In 1918 and 1921, the Forest Service built a firetower on the summit, but soon abandoned it because of the difficulty of supplying it—and because views from the summit were too often blocked by fog.

In 1929 a local entrepreneur named Wade Dean filed a claim to the summit, built mule and horse trails, hauled up mining equipment, and started to extract sulfur. Active mining continued until 1959. Trains of pack stock were used to supply the miners. Their route, up the south side via Morrison Creek and Cold Springs, is today the easiest and most popular climbing route up the mountain. The ascent crosses a long snowfield and then follows a pumice ridge to the summit. While there are no technical difficulties, Mount Adams is a major mountain—the second-highest in Washington and the third-highest in the Cascades. If you attempt the climb, you should have an ice ax, crampons, and plenty of warm clothes.

From the PCT, you can access the summit route from Round the Mountain Trail 9, which joins the PCT in the Mount Adams Wilderness.

Mount St. Helens

Mount St. Helens is not on the PCT, but lies about 30 miles to the west of Mount Adams on almost an identical line of latitude. Early pioneers, using the mountains as points of reference, would often confuse the two. In those days, Mount St. Helens was 9,677 feet tall, a beautifully symmetrical peak, sometimes called the Fujiyama of America. Interestingly, it was the first Cascadian peak to be climbed strictly for pleasure, or recreation, rather than for economic, scientific, or military reasons. The first ascent was made by Thomas J. Dryer, founder of The Oregonian, on August 27, 1853.

Mount St. Helens is the youngest of the stratovolcanoes, its origins dating back about 40,000 years. But the pre-1980 summit was only about 15,000 years old, and the visible part of the present-day volcano took shape only about 2,200 years ago, well after the Ice Age. The mountain’s relative youthfulness explains the symmetry it had before the 1980 eruption: It was too young to have suffered from significant erosion.

Even before its 1980 eruption, Mount St. Helens was more active and violent than any other volcano in the contiguous 48 states. Klickitat Indians called it Tah-one-la-clah—Fire Mountain—because of its history of eruptions.

Its eruption on May 18, 1980, was cataclysmic. An explosion equivalent to 30 million tons of TNT blew the top 1,300 feet of the mountain into the stratosphere, produced the largest avalanche in recorded history, killed 57 people, destroyed 150 square miles of forest, created a 4-mile-long lava flow with temperatures between 600 and 1400 degrees Fahrenheit, melted the upper 45 feet of St. Helens Glacier, clogged channels in the Columbia River with sediment for months, and blew 2 to 5 inches of ash as far away as Montana. The mountain, now 8,364 feet tall, is managed by Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument.

Goat Rocks Wilderness

William O. Douglas wrote, “The Goat Rocks seem holy to me—of this earth and yet apart from it. They are sanctuaries built on such a vast scale that he who approaches them from the south is certain to feel humble and reverent.”

The region was sacred to the Yakima, who believed that is was the home of La-con-nie, God of the Goats. And although no PCT hikers have encountered the goat god, there are plenty of his charges to be seen.

The dramatic main ridge of the Goat Rocks is the remains of an ancient stratovolcano that was once as high as Mount Hood or pre-eruption St. Helens. The oldest rocks in the area—some 120 million to 140 million years old—originated from volcanic flows beneath the sea that were brought to the surface by the collision of the tectonic plates. About 3.8 million years ago, volcanic activity began to build the Goat Rocks, and between 1 million and 3 million years ago, the stratovolcano was formed. Over time, its explosion and erosions combined to sculpt the craggy terrain that is at the heart of this stark and dramatic landscape.

Mountain goat

The landscape is hands-down the most beautiful on southern Washington’s PCT. It is also the southernmost range of mountain goats, and one of the places where you have the best chance of seeing these agile high-country animals. Standing still, they sometimes look like big yellowish-white rocks. If you see one move, look closely, because mountain goats usually travel in herds. You may be lucky enough to see 20 or 30 at a time.

Goat Rocks Wilderness

Mountain goats live above the tree line in territory so rugged that they are largely free of predators (if only because no predator can catch them as they leap and gallop over precipices and cliffs). Somehow they manage to find enough to eat—twigs, grasses, flowers, herbs, kinnikinnick (berries that grow in the high country), and lichen. They are superbly adapted for their chosen lifestyle. A shaggy outercoat and a soft woolly undercoat protect them from bitter winds and frigid cold. Their feet are equipped with cushioned skid-proof pads that work better on the slick rock and slippery ice than any Vibram sole yet invented by humans.

Toponyms

Mount St. Helens was given its name by George Vancouver to honor a British diplomat by that name. Mount Rainier commemorates a British admiral, and Mount Hood was named for another British naval officer. Mount Baker is named for one of Vancouver’s lieutenants. In 1839, Hall Jackson Kelly, an early advocate of the colonization of Oregon, tried to turn the Cascades into a presidential range. Hood was to be renamed Mount Adams, St. Helens would become Mount Washington, The Sisters were to be renamed Madison, and Shasta would become Jackson. At the time, cartographers had only rudimentary maps, which didn’t even show the presence of the mountain today known as Adams. In any event, the names were never changed. Only the name Adams stuck: It was mistakenly written in on a cartographer’s map on a spot 40 miles distant from where it was supposed to be—and coincidentally there was an unnamed mountain there in need of a name (at least so far as European Americans were concerned; Indians in the region had long since been able to identify the mountain as Klickitat, a son of Manitou).

Indian Legends

Native American legends reflect the fact that each of the mountains has a very different character—some more explosive, others more beautiful. There are parallels with Old World mythology. Like the Greek gods who once inhabited Mount Olympus, the Native American gods inhabited the great volcanoes. Like their Greek counterparts, they periodically erupted to express anger at each other or at humans. And Native American legends include a tale similar to the story of Noah’s Ark, in which Mounts Jefferson, Shasta, and Baker offered refuge from the floods.

Mount Rainier from Goat Rocks

In one story, Klickitat (also known as Pahto, or Mount Adams) and his brother Wy’east (Mount Hood) are at it again, fighting over La-Wa-La-Clough (Mount St. Helens). (You may remember her as the beautiful incarnation of the old crone who had been turned into a lovely maiden by the god Manitou when she tried to protect the Bridge of the Gods.) La-Wa-La-Clough preferred Pahto. In a rage, Wy’east struck Pahto and flattened his head. Pahto, in defeat, stopped smoking, and never again lifted his head.

HIKING INFORMATION

HIKING INFORMATION

Seasonal Information and Gear Tips

The elevations of the trail in southern Washington are, with the exception of the Goat Rocks Wilderness, considerably lower than the elevations in northern Washington. Generally, the trail is snow-free by mid-July. (Of course, winter snow accumulations vary, so you’ll have to check with the PCTA. Or call the particular national forest in which you plan to hike.) August is usually a good month, and in years of lower-than-average snowpack, you may not have much of a bug problem. The later in the month you hike, the fewer bugs you’ll have to swat. Hiking just after the snowmelt does have its reward: the beautiful alpine wildflower bloom.

September is bug-free, but weather-wise it’s a crapshoot. This is a great time of year for locals to be on the trails. After Labor Day, the crowds are gone, the mosquitoes are gone, and if you live nearby, you have the flexibility to respond to changing weather conditions. In some years, September offers sunshine and Indian summer; in other years, you’ll get weeks of nonstop rain, cold, and even snow at the higher elevations. From late August on, huckleberries are plentiful, feeding not only your taste buds, but also your eyes with their brilliant russet foliage. In most years, the hiking season in this section ends sometime in October.

• Bring bug protection. July is mosquito season, which can last well into August. They grow ’em fierce and hungry here. Especially buggy sections vary from year to year (and even from day to day), but wherever there’s a lot of standing water and slushy snowmelt, you can expect buzzing company, especially in the Indian Heaven Wilderness (known locally as Mosquito Heaven) and in the lowland pond-filled section between Mount Adams and the Goat Rocks.

• Good rain gear is necessary, particularly at the beginning and end of the hiking season.

Thru-hikers’ Corner

Northbound thru-hikers should concentrate on making mileage here: The trail is easy, and time is at a premium. In late September, you’ll probably need to pick up an extra layer of clothes, because the nights can be cold, there can be long periods of cold rain, and you might even get a little snow.

Southbounders who have made it this far can rest assured that they’ve been through the bulk of the tough stuff. However, don’t get rid of your ice ax just yet. It’ll come in handy on the Packwood Glacier, and you may need it for the higher elevations around Mount Adams.

Best Short Hikes

• You can day-hike into the Big Lava Bed from Crest Campground, located on Forest Road 60.

• Mount Adams Wilderness offers a 25-mile hike that features superb scenery, excellent campsites—and one cardiac-challenging climb. Enter the wilderness at the trailhead at the junction of Forest Roads 23 and 8810 (it’s 82.3 miles into this section). Your first miles are all uphill as you climb to just beneath the summer snow-line. After walking halfway around the mountain, you end the hike at Road 5603. You should plan to have a car at this end; there isn’t much traffic on the road.

• From U.S. Highway 12 at White Pass, it’s a 21-mile hike south across the Goat Rocks. It’s an easy 2-day hike—but you could certainly spend 3 days exploring side trails and the high country. Take Trail 96 to Road 405–it’s the shortest route in and out. For a longer hike (42.9 miles), continue on the PCT until the junction with Road 5603.

Resupplies and Trailheads

Cascade Locks is the most commonly used.

Cascade Locks (Oregon) (mile 0). This on-trail resupply just off Interstate 84 near the Bridge of the Gods offers everything you are likely to need: motels, restaurants, supermarket, a post office, public campground by the river. For gear, nearby Hood River has several outfitters. (Thru-hikers taking the road rather than the trail between Cascade Locks and Panther Creek Campground can also resupply 3.2 miles up the road in Stevenson or 4.4 miles farther, in Carson; both Washington towns have stores, motels, and restaurants.) Stock up: The next convenient resupply is at White Pass, 147.5 miles from Cascade Locks (only 126.7 miles if you take the shortcut road walk; see page 240). Post office: General Delivery, Cascade Locks, OR 97014

Panther Creek Campground (Washington) (mile 35.5) on Forest Road 65. No convenient resupply, but this is a good place to start a hike.

Crest Campground (mile 51.0) on Forest Road 60. No convenient resupply, but this is a good place to start a hike south into the Big Lava Bed or north into the Indian Heaven Wilderness.

Road 5603 (mile 94.3). No convenient resupply, but this is an excellent place to start a hike either south into the Mount Adams Wilderness or north into the Goat Rocks.

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press