Alpine Lakes Wilderness near Waptus Creek

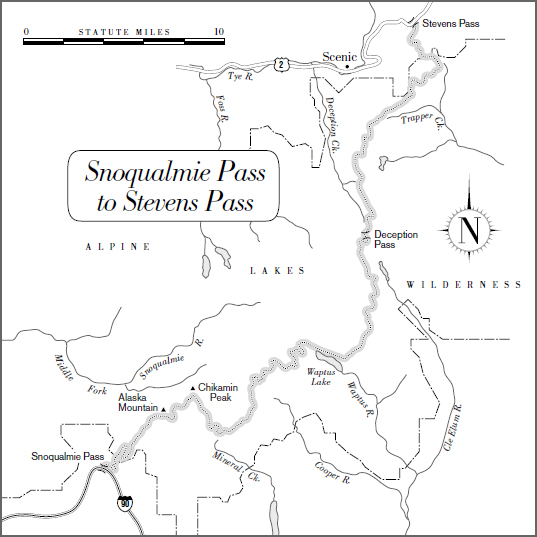

Snoqualmie Pass to Stevens Pass

75 miles

From the ridges of central Washington just before Snoqualmie Pass, you get a glimpse ahead into the North Cascades, which block the horizon like an impenetrable wall. Isolated and rugged, serrated and snaggle-toothed, the North Cascades rival California’s High Sierra for scenic mountain vistas, yet are completely different in character.

By comparison to the southern Cascades, a profile map of the North Cascades looks positively terrifying. Ascents and descents of more than 3,000 feet are common, and are sometimes lined up like a series of hurdles. Plan conservative mileage here. Even though most of the climbs are extremely gentle and well-graded, going up and down 3,000 feet at a time can wear out even strong hikers.

Alpine Lakes Wilderness near Waptus Creek

This 75-mile section traverses the exorbitantly scenic Alpine Lakes Wilderness, the southernmost section of the North Cascades. Because of both its wild rugged beauty and its proximity to Seattle, the Alpine Lakes Wilderness is one of the most popular hiking destinations in Washington. The trailhead at Snoqualmie is only an hour from downtown Seattle—and reachable by Greyhound bus (there’s a regularly scheduled stop at the Time Wise Deli at the pass).

Most of this section is in wilderness, making it one of the longest roadless stretches on the entire PCT. Thru-hikers motivated by the fear of winter weather can do this section is 4 long days. Others would be better advised to take 5, 6, or even 7 days to savor the views—and recover from the climbs.

THE ROUTE

In the first 11 miles of this section, the trail gains more than 3,000 feet as it ascends from Snoqualmie Pass to the high ridges of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness. You’ll be amply rewarded for your effort with views of Mount Rainier, Glacier Peak, Mount Thompson, Mount Stuart, and later of Alta Mountain, Three Queens, and Mount Daniel.

Note: In a dry year, or late in the season, watch your water, because some of the climbs can be quite dry. On a sunny day, the exposed slopes can be surprisingly hot. If you miscalculate, you may be able to slake your thirst in the occasional stagnant pool or late-lingering snowfield.

Throughout this section, you will spend much of your time going up or down steep sidewalls, formed when glaciers scoured out the valleys. On these long, alder-choked switchbacks, there are very few places to camp. So when planning your day, consider that if you start up (or down) a 3,000-foot slope in the late afternoon, you’re probably going to have to make it all the way to the top (or bottom) before you’ll be able to find even the most basic bivouac site.

The trail is actively maintained, but the crews sometimes can’t keep up with deterioration caused by erosion on the steep slopes. You can also expect some tedious miles on the steep sidewalls where alder can quickly overrun the trail.

The PCT leaves the Alpine Lakes Wilderness 4.5 miles short of Stevens Pass. These last miles are less dramatic than those in the heart of the wilderness, and they can be tedious, with some stiff ups and downs. You pass several dirt roads and a ski resort before finally reaching the section’s end at U.S. Highway 2. Short-term hikers not intent on doing the entire PCT might better enjoy a shortcut that descends on Trail 1060 past beautiful Surprise Lake, getting to Highway 2 in 4 miles. At that point, you are 6 miles west of Stevens Pass and 8 miles from Skykomish. Note: If you reverse direction and take this alternate route southbound, be prepared to for a long, steep climb!

WHAT YOU’LL SEE

The North Cascades

Geology confirms what common sense infers: The North Cascades are very different mountains than their cousins to the south.

The Cascades of Oregon and southern Washington are dominated by the line of volcanic giants—The Sisters, Jefferson, Hood, Adams, St. Helens, Rainier. With the exception of the Goat Rocks, the mountains and ridges on the PCT’s route through Oregon and southern Washington are rounded and gentle.

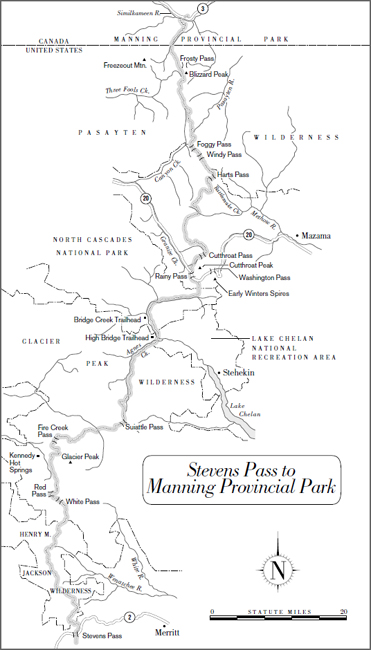

In contrast, the North Cascades have only two major volcanoes, Mount Baker and Glacier Peak (both visible from the PCT in the section covered in chapter 18). But while these big volcanoes (along with Mount Rainier to the south) might dominate the skyline, it is the lower mountains that give the North Cascades their fierce, wild character: This is a landscape of steep peaks, narrow gorges, and sharp angles cut by ice and snow. The North Cascades boast more than half of the glaciers in the contiguous 48 states.

Clinton Clarke described the terrain of the North Cascades as “the most primitive and roughest in the [contiguous] United States.”

The trail described in chapters 17 and 18 is thus steeper, wilder, more rugged, and higher than the trail to the south. In the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, the trail several times climbs to nearly 6,000 feet. (And in chapter 18, it goes even higher: Just south of the Canadian border, the trail stays largely above 6,000 feet for 33 miles, and reaches the highest point on Washington’s PCT at 7,126 feet.) Because tree line drops about 300 feet for every 100 miles of latitude, elevations of 6,000 and 7,000 feet this far north mean exposed and windswept trails. The difference is noticeable. While the timber on Mount Hood grew up to elevations of about 6,000 feet, in the North Cascades the trees start to thin out at around 5,000 feet; only a few hundred feet higher, there’s nothing left but shrubs. For hikers this means fine views in good weather, but potentially dangerous exposure in bad.

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press

The differences between the southern Cascades and the North Cascades are grounded in their different geological histories. The North Cascades are an old range, formed about 10 million years ago. Unlike the Cascades of Oregon and southern Washington, they are not made of igneous rock (products of volcanic activity), but rather of metamorphic and sedimentary rock that has been uplifted and eroded. Both the southern and North Cascades are the product of tectonic activity—the result of collisions that occurred when the earth’s plates shifted. But in the southern subrange, this tectonic activity led to subduction, and volcanism shaped the landscape. In the North Cascades, the collision of plates uplifted the mountains, which were then given their current shape by the sculpting action of ice, water, and wind.

During the Ice Age the North Cascades were further uplifted. As a result, the peaks grew higher while at the same time ice was cutting into the valleys, making them lower. The result is a maze of sharp peaks and narrow gorges, of cirques, moraines, and vertical headwalls. The few valleys that exist are deeply cut, with flat floors and steep sides. For hikers, this means a vertical landscape of major elevation changes. William O. Douglas quotes a hiking partner thus: “This is a country where one looks either up or down.”

Access into the North Cascades has always been difficult. Unlike the southern Cascades, which are traversed by the Columbia River, the North Cascades are unbroken, not crossed by any rivers. Water that drains to the west finds its way fairly directly to the Pacific Ocean. But water that drains to the east has a longer journey. It is forced by the mountains to first flow southward, where it runs into the Columbia River and thence to the Pacific.

Nor is there convenient access by land. Indians who crossed the mountains to trade, hunt, fish, and gather food in the rich old-growth forests used several trails over the high passes, including Suiattle Pass, Cloudy Pass, and White Pass. Later, these trails were used by early European American trappers and traders. But as European settlement began for real, these passes failed to provide a feasible route through the mountains for wagon roads and railroads—although not for lack of trying.

Alexander Ross, an explorer for the American Company based at Fort Okanogan, crossed over Cascade Pass in 1814 and reported that, “A more difficult route of travel never fell to man’s lot.” As a result of reports like this, the first railroads crossed the Cascades farther to the south, through Stampede Pass and then through Snoqualmie Pass. The railroad through Stevens Pass was not built until 1893.

In the period between 1880 and 1900, prospectors located some gold, copper, silver, lead, and zinc in the North Cascades. But the hard rock surfaces were difficult to prospect and roads were almost impossible to build.

Snoqualmie Pass

With its relatively low elevation and gentle grades, Snoqualmie Pass is the best railroad and highway pass in Washington, and indeed it is the only pass in Washington that has both a railroad and an interstate highway.

The first survey to try to identify a route through the Cascades took place in 1853, when George R. McClellan (later a Union general in the Civil War) was commissioned for the job by the governor of Washington Territory. His report was full of errors. Of the 11 passes he considered possibilities for a railroad route, he did not include Snoqualmie—the widest and gentlest pass with the fewest engineering obstacles.

The survey was completed by someone else in 1854, but scandals and land schemes delayed selection of Snoqualmie as a railroad route until 1880. The route through Stampede Pass (which the PCT crosses just to the south, in the section covered in chapter 16) was actually completed first.

In 1865 the first wagon road crossed the pass. In 1914 it became a highway that was the precursor of Interstate 90, now the busiest crossing of the Cascades in Washington.

Stevens Pass

At the northern end of this section, Stevens Pass is also crossed by a railroad. The pass is named for John F. Stevens, the engineer for the Great Northern Railway who in 1890 surveyed and recommended the route.

At 4,062 feet in elevation, Stevens Pass was a much more difficult proposition than Snoqualmie Pass, elevation 3,030 feet. The first rail route over Stevens Pass, which opened in 1893, used switchbacks to climb the steep grades. (Just north of Stevens Pass, the PCT follows some of this old railway grade.) Between 1897 and 1900, a 3-mile tunnel was added, eliminating the need for some of the switchbacks. In 1929 the route used today was constructed, which uses an 8-mile-long tunnel. Skykomish, on the western side of the tunnel, became a railroad town—a major hub of activity on the western slope. (The name is that of a local Indian tribe; it translates as inland people.)

Ascending into Alpine Lakes Wilderness

Alpine Lakes Wilderness

Aptly called the “backyard wilderness,” the Alpine Lakes Wilderness is easily accessible from metropolitan Seattle. Nestled between Interstate 90 and Highway 2, the 393,000-acre wilderness has become one of the most popular hiking destinations in Washington. It was also the site of a long and protracted battle between timber companies, the Forest Service, recreation groups, and conservation organizations.

The battle dates back almost 70 years. In the 1930s, conservation and recreation groups became concerned about the long-term prospects for this beautiful but threatened area. The Forest Service was traditionally sympathetic to the timber companies; its efforts at protection had been limited to identifying parts of the region that might be considered suitable for potential wilderness status. Meanwhile, the conservation groups—The Mountaineers, the North Cascades Conservation Council, the Sierra Club, and the Mazamas—made the mistake of trying to deal as separate entities, with similar but independent agendas, with the Forest Service. The waters became further muddied when recreation groups started lobbying for and against each other’s ideas.

The passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964 gave conservation groups some leverage by taking away the right to designate wilderness from the Forest Service and giving it to Congress, but still no resolution was reached. Then, in 1968, the North Cascades National Park was created, putting some land that had been under Forest Service management under the control of the National Park Service. With the Cascades National Park lost to them, timber interests now turned their attention back to the Alpine Lakes area. This new threat motivated the four conservation-oriented organizations to mobilize and unite. In 1968 they agreed to act together by forming ALPS (Alpine Lakes Protection Society) and briefing members of Congress on the details of the situation—including maneuvering by the Forest Service, timber interests, and developers, all of whom wanted to prevent wilderness designation. Finally, in 1976, Congress established the Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area.

Today, overuse of the area is still a problem. Now, however, users come armed not with chain saws but with trekking poles. Because of its accessibility, Alpine Lakes Wilderness on a sunny August weekend can be jampacked with hikers, which has led to a permit system and strict camping and fire regulations. The last chapter of the story of the protection of this magnificent area remains to be written.

HIKING INFORMATION

HIKING INFORMATION

Seasonal Information and Gear Tips

Here again, the hiking season is July through early October.

• Typical summer gear for this section is three-season alpine: shorts and T-shirts for walking during the day and a light layer of polypro for night. Bring a lightweight fleece layer, a hat, and rain gear just in case.

• In early or late season (early and mid-July or September and October), you’ll want another layer.

• If you have a choice, go with a fiber-fill rather than a down sleeping bag. Fiber-fill bags retain their heat insulating capacity better if they get wet.

• In July and early August, consider taking a tent rather than a tarp for mosquito protection.

Thru-hikers’ Corner

This section is generally a good one for northbound thru-hikers, if the weather holds. Northbounders arrive in late August or September, which is Washington’s prime hiking season.

For southbounders, passage is still touch-and-go because of the possibility of lingering snow. Early in the season, you may find the high country still impassable. However, one thing that is true of southbound thru-hiking is this: If you’ve made it through the Glacier Peaks Wilderness to the north, everything to the south is easier (until, that is, you face new and different challenges in the Sierra and southern California). How much snow you’ll face in the Alpine Lakes Wilderness depends on how early you start your hike and what the snow accumulation has been that year. Hang onto your ice ax.

Best Short Hikes

This roadless 75-mile section can’t be conveniently divided into shorter hikes. However, day hiking north of Snoqualmie Pass offers strong hikers a chance to get a good uphill workout with a scenic reward—6.4 miles takes you 2,400 feet to the Cascade Crest. Going back is a lot easier! (Note: In the Alpine Lakes Wilderness, even day hikers need permits. See appendix A.)

Resupplies and Trailheads

Snoqualmie Pass (mile 0) at Interstate 90 is approximately 50 miles east of Seattle and is accessible via Greyhound Bus. The pass is right on the trail. It offers a motel, a post office, and a couple of basic stores and restaurants. Post office: General Delivery, Snoqualmie Pass, WA 98068

Paul Woodward, © 2000 The Countryman Press