During the Archaic period the peoples of Middle America made great progress in agriculture. They successfully domesticated squash (about 8000–7000 BC), corn (5000–4000 BC), cassava (5000–4000 BC), and cotton (2600 BC). After obtaining a dependable food supply from agriculture, Middle American peoples settled into villages and had more time to devote to activities such as the arts, architecture, and commerce. Eventually they developed sophisticated civilizations. The great civilizations of Middle America included the Olmec, the Maya, Teotihuacán, the Toltec, and the Aztec.

The first great Indian culture in Middle America was that of the Olmec. They lived on the hot, humid lowland coast of the Gulf of Mexico in what is now southern Mexico. San Lorenzo, the oldest known Olmec center, dates to about 1150 BC. At that time the rest of Middle America had only simple farming villages.

The Olmec built large towns where they came together to trade and hold religious ceremonies. The most important were San Lorenzo, La Venta, and Tres Zapotes. They were home to the upper classes of priests and other leaders, who lived in well-made stone houses. These leaders commanded the work of craftsmen and laborers. Farmers lived in the surrounding countryside. Their work supported the upper classes. Corn was the most important crop.

The flat-faced, helmeted “colossal heads” carved by the Olmec people measured up to 9 feet (nearly 3 meters) in height. Adalberto Rios Szalay—Sexto Sol/Getty Images

San Lorenzo is famous for its extraordinary stone monuments. Most striking are the “colossal heads,” which are human portraits on a massive scale. They measure up to 9 feet (nearly 3 meters) in height and have flat faces and helmetlike headgear. They may represent players in a sacred rubber-ball game. La Venta is marked by great mounds, a narrow plaza, and several other ceremonial enclosures. Between about 800 and 400 BC it was the most important settlement in Middle America.

The artifacts left by the Olmec range from the huge stone sculptures to small jade carvings and pottery. Much Olmec art depicted a god that is a cross between a jaguar and a human infant, often crying or snarling with open mouth.

The exotic materials used by Olmec artists and craftsmen suggest that the Olmec controlled a large trading network over much of Middle America. Obsidian, a form of volcanic glass used for blades, flakes, and dart points, was imported from highland Mexico and Guatemala. Most imported goods were used to make luxury items. Iron ore, for example, was used to make mirrors.

The Olmec may have developed the first writing system in the Americas. In the late 20th century a stone slab engraved with symbols, or hieroglyphs, that appear to have been Olmec writing was discovered in the village of Cascajal, near San Lorenzo. The Cascajal stone dates to about 900 BC. In the 21st century inscribed carvings similar to later Mayan hieroglyphs were found at La Venta.

Olmec culture began to fade around 400 BC. However, its influence spread north to central Mexico and south to Central America. Among those influenced by the Olmec were the Maya and Teotihuacán civilizations.

The Maya occupied a nearly continuous territory in southern Mexico, Guatemala, and northern Belize. Before the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Central America, the Maya possessed one of the greatest civilizations of the Western Hemisphere. The rise of the Maya began in about AD 250, and what is known to archaeologists as the Classic Period of Mayan culture lasted until about AD 900. The Maya practiced agriculture, built great stone buildings and pyramid temples, worked gold and copper, and made use of a form of hieroglyphic writing that has now largely been deciphered.

Mayan ruins at Xunantunich, Belize, c. AD 650–890. © Doug Waugh/Peter Arnold, Inc.

As early as 1500 BC the Maya had settled in villages and had developed an agriculture based on the cultivation of corn, beans, and squash. By AD 600 cassava was also grown. They practiced mainly slash-and-burn agriculture. First, toward the end of the dry season, a patch of forest was selected for planting. Next, a band of bark would be removed from the trunks of larger trees (the “slash”), which caused the tree to die and shed its leaves. Then the undergrowth and smaller trees were burned and cleared away. The new field was ready to be planted in time for the first rains. After a few years of planting, the fertility of the soil declined, weeds increased, and the field was abandoned to the forest. The Maya also used advanced techniques of irrigation and, in places with steep land, terracing. Terracing involved leveling off the slopes to make a series of stepped fields.

The corn god (left) and the rain god, Chac. Drawing from the Madrid Codex (Codex Tro-Cortesianus), one of the Mayan sacred books. Courtesy of the Museo de América, Madrid

By AD 200 the villages and ceremonial centres of the Maya had developed into cities containing temples, pyramids, palaces, courts for playing ball, and plazas. At its height, Mayan civilization consisted of more than 40 cities, each with a population between 5,000 and 50,000. Among the main cities were Tikal, Uaxactún, Copán, Bonampak, Dos Pilas, Calakmul, Palenque, and Río Bec. The peak Mayan population may have reached 2 million people, most of whom lived in the lowlands of what is now Guatemala.

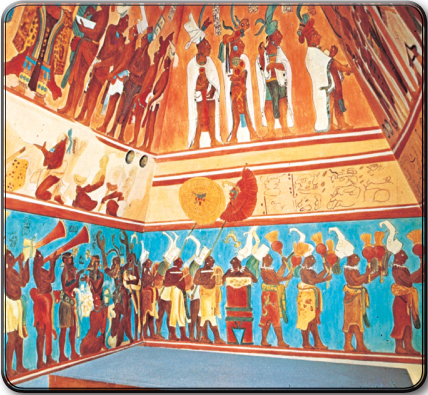

Mayan fresco from Bonampak, original c. AD 800, reconstruction by Antonio Tejeda; in Chiapas, Mexico. Ygunza/FPG

To build their cities, the Maya quarried immense quantities of building stone (usually limestone), which they cut using harder stones such as chert. The workers were unaided by draft animals and wheeled carts, making hauling and construction very labor intensive.

The Temple of Inscriptions, Palenque, Mexico. The Maya considered mountains to be sacred places, and they represented mountains in their cities by building pyramidal stone temples. C. Reyes/Shostal Associates

Jaina pottery figurine, Late Classic Maya style, from Campeche, Mexico; in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. Height 15.5 cm. Courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

The Maya developed an elaborate and beautiful tradition of sculpture and relief carving. The temples and palaces of Mayan cities were richly ornamented with narrative, ceremonial, and astronomical reliefs and inscriptions that have ensured the stature of Mayan art as premier among American Indian cultures. Architectural works and stone inscriptions and reliefs are also the chief sources of knowledge about the Maya.

Among the Maya, as in other societies of Middle America, the rulers and nobility were believed to have been created separately from commoners. The result was a highly stratified society in which the work of peasant farmers freed the nobility and the priests from daily drudgery in the fields. The elite used the surplus time to build the cities, pyramids, and temples and to pursue intellectual studies.

Scholars in the mid-20th century mistakenly thought that Mayan society was composed of a peaceful priestly class supported by a devout peasantry. The Maya were believed to be completely absorbed in their religious and cultural pursuits, in favorable contrast to the more warlike peoples of central Mexico. But more recent decipherment of Mayan writing has provided a truer picture of Mayan society and culture. Many hieroglyphs depict the histories of the Mayan dynastic rulers, who waged war on rival Mayan cities and took their aristocrats captive. These captives were then tortured, mutilated, and sacrificed to the gods.

The priestly class was responsible for the impressive development of mathematics and astronomy among the Maya. In mathematics, positional notation and the use of the zero represented a pinnacle of intellectual achievement. Mayan astronomy underlay a complex calendar involving an accurately determined solar year (18 months of 20 days each, plus an unlucky 5-day period), a sacred year of 260 days (13 cycles of 20 named days), and a variety of longer cycles culminating in the Long Count, based on a zero date in 3113 BC. Mayan astronomers compiled precise tables of positions for the Moon and Venus and were able to predict solar eclipses.

One of the great intellectual achievements of Mayan civilization was writing. The Maya developed a system of hieroglyphic writing that they used to record calendars, astronomical tables, dynastic history, taxes, and court records. They made paper from the inner bark of wild fig trees and wrote their hieroglyphs on books made from this paper.

Mayan religion was based on a pantheon of nature gods, including those of the Sun, the Moon, rain, and corn. The priests were responsible for an elaborate cycle of rituals and ceremonies. Torture and human sacrifice were fundamental religious rituals that were thought to guarantee fertility, demonstrate piety, and appease the gods. If such practices were neglected, cosmic disorder and chaos were believed to result. The drawing of human blood was thought to nourish the gods and was thus necessary to achieve contact with them. Thus the Mayan rulers, as the intermediaries between the Mayan people and the gods, had to undergo ritual bloodletting and self-torture.

The Classic Maya civilization declined rapidly after AD 900 for reasons that remain uncertain. Some scholars have suggested that armed conflicts and the exhaustion of farmland were responsible, but discoveries in the 21st century led scholars to put forth other explanations. One cause was probably the war-related disruption of river and land trade routes. Other contributors may have been deforestation and drought.

During the Post-Classic Period (900–1519), cities such as Chichén Itzá, Uxmal, and Mayapán in the highlands of the Yucatán Peninsula continued to flourish for several centuries. By the time the Spanish conquered the area in the early 16th century, most of the Maya had become village-dwelling farmers who practiced the religious rites of their ancestors. In the early 21st century more than 5 million people still spoke some 70 Mayan languages.

Located near present-day Mexico City, Teotihuacán was the greatest city of the Americas before the arrival of Europeans. At its height in about AD 500, it covered some 8 square miles (20 square kilometers) and may have housed more than 150,000 people. At the time it was one of the largest cities in the world. It was the region’s major economic and religious center.

The origin and language of the residents of Teotihuacán (called Teotihuacanos) are unknown. Perhaps two-thirds of them farmed the surrounding fields. Others made distinctive pottery or worked with obsidian, a form of volcanic glass that was used to make weapons, tools, and ornamentation. The city also had large numbers of merchants, many of whom had emigrated there from great distances. Teotihuacán carried on trade with distant regions, and the products of its craftsmen were spread over much of Middle America. The priest-rulers who governed the city staged grand religious pageants and ceremonies that often involved human sacrifices.

The remains of the ancient city of Teotihuacán in Mexico include pyramids, temples, and palaces. Gianni Tortoli-Photo Researchers

The city contained great plazas, temples, palaces of nobles and priests, and some 2,000 single-story apartment compounds. The main buildings were connected by a great street called the Avenue of the Dead. The most prominent feature of Teotihuacán was the Pyramid of the Sun. It dominated the central city from the east side of the Avenue of the Dead. The pyramid is one of the largest structures of its type in the Western Hemisphere, reaching a height of 216 feet (66 meters). The northern end of the Avenue of the Dead was capped by the Pyramid of the Moon and flanked by platforms and lesser pyramids. The second largest structure in the city, the Pyramid of the Moon rose to 140 feet (43 meters).

Near the exact center of the city and just east of the Avenue of the Dead was the Ciudadela (“Citadel”). It was a kind of sunken court surrounded on all four sides by platforms supporting temples. In the middle of the sunken plaza stood the Temple of Quetzalcóatl, the Feathered Serpent god. Numerous stone heads of the god projected from the walls of the temple.

The Pyramid of the Moon, the second largest pyramid in Teotihuacán, stands at the northern end of the Avenue of the Dead. Luis Acosta/AFP/Getty Images

In about AD 750, central Teotihuacán burned, possibly during a rebellion or civil war. Although parts of the city were occupied after that event, much of it fell into ruin. Nevertheless, its cultural influence spread throughout Middle America.

The most powerful and culturally advanced civilization in central Mexico from about 900 to 1200 was that of the Toltec people. Toltec culture revolved around the urban center of Tula.

Under the ruler Topiltzin, the Toltec united a number of small states into an empire. Topiltzin introduced the cult of Quetzalcóatl, and he took the name of that god. This cult and others appeared in important Mayan cities to the south in Yucatán, such as Chichén Itzá and Mayapán, and to other Middle American peoples. The Toltec military orders of the Coyote, the Jaguar, and the Eagle also appeared among the Maya. The spread of these cultural traits shows the wide influence of the Toltec.

The exact location of Tula is unknown, but scholars believe it was located near the modern town of Tula, about 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of Mexico City. The town covered at least 3 square miles (some 8 square kilometers) and probably had a population in the tens of thousands. The heart of the town consisted of a large plaza bordered on one side by a five-stepped temple pyramid, which was probably dedicated to Quetzalcóatl. Other structures included a palace complex, two other temple pyramids, and two ball courts. Surrounding Tula were fields watered by irrigation ditches. There the Toltec grew corn, squash, and cotton.

Along with building great palaces and pyramids, the Toltec were known for their metalwork and sculpture. They made fine objects in gold, silver, and copper, which they obtained through an extensive trade network. Their sculptures included the Chac Mools—reclining male figures with a dish resting on the stomach. Thought to represent the rain god Chac, Chac Mools were probably used to hold the hearts of people sacrificed during religious ceremonies.

Beginning in the 1100s the nomadic Chichimec peoples invaded Toltec territory from the north. The invaders destroyed Tula in about 1150 and ended Toltec dominance of central Mexico. Among the Chichimec were the Aztec, who created the next great culture in the region.

The dominant group in Middle America when the Spanish arrived was the Aztec. Through conquest, the Aztec had created an empire with a population of 5 to 6 million people. Their language, Náhuatl, spread throughout Middle America as their empire expanded. The capital of the Aztec Empire was Tenochtitlán, on the site of modern-day Mexico City.

The basis of the Aztec’s success in creating a great state and ultimately an empire was their remarkable system of agriculture. The Aztec planted a great many crops, of which corn, beans, and squash were the most important. Others included chili peppers, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava, cotton, cacao, pineapples, papayas, peanuts, and avocados. Many crops could be raised only in certain environmental zones, which encouraged trade between regions.

Farming was most intensive in the highlands, where farmers used a variety of special techniques. In places with sloping land, farmers created terraces to control erosion. In some places people built irrigation canals to water their fields. A unique feature of Aztec agriculture was the use of chinampas. These artificial islands were built up above the surface of a lake using mud and vegetation from the lake floor. After settling, the chinampa was a rich planting bed. Tenochtitlán depended on chinampas for much of its food.

In the lowlands, people typically practiced slash-and-burn farming, often supplemented by “raised-field” farming. In the latter method, small earthen hills were built for planting in shallow lakes or marshy areas, similar to the chinampas of the highlands. In addition, farmers constructed terraces in some lowland regions.

With their long history of farming, the Aztec established villages earlier than most other Indians. The basic requirement for settlement was water, and the main settlement sites were near major rivers and high valley lakes. Through the years, as their farming skills improved, their settlements grew larger. Some developed into great cities, such as Tenochtitlán.

The type of house in which a person lived was based on wealth and social class. The upper classes lived in two-story palaces of stone, plaster, and concrete. Merchants and the rest of the middle class typically had one-story adobe houses. Each house was built around a patio and raised on a platform for protection against lake floods. Commoners lived in small huts.

The advanced culture of the Aztec is especially remarkable considering that their technology was quite simple. Their tools were made mostly of chipped and ground stone, and with no large domesticated animals available, all power was based on human energy. In farming, the Aztec used stone axes to clear vegetation and wooden digging tools to work the soil. They ground corn into dough on milling stones called manos and metates.

A notable skill of the Aztec was stone sculpture. The most prevalent sculptures were images of the gods carved for display in temples and public spaces. Aztec woodworkers made large dugout canoes, sculpture, drums, stools, and a great variety of household items. The Aztec also worked metals—gold, copper, and sometimes silver—to produce jewelry and some tools. Their ceramics included pottery, figurines, and musical instruments.

Aztec society was based on a complex hierarchy. At the top was the ruling class, consisting of priests and nobles. At the bottom were the serfs and slaves. Serfs worked on private and state-owned rural estates. Slaves were used mostly for human sacrifice. A man could move up in class through promotions, usually as a reward for valor in war, and women were similarly rewarded for braving the dangers of child-birth. Certain occupations—such as merchants, goldsmiths, and featherworkers—were given more prestige than others.

Aztec earth goddess Coatlicue. The Aztec were skilled sculptors who often carved images of their gods for public display. DEA/G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini Picture Library/Getty Images

Trade linked the far parts of the Aztec Empire with Tenochtitlán. Agricultural products, luxury items, and other goods were exchanged at well-organized markets. Soldiers guarded the traders, and troops of porters carried the heavy loads. Canoes brought the crops from nearby farms through the canals to markets in Tenochtitlán. Trade was carried on by barter because the Aztec had not invented money. Change could be made in cacao beans.

The intellectual achievements of the Aztec included the creation of an accurate calendar. It was based on observation of the heavens by the priests, who were also astronomers. The Aztec calendar was common in much of the region. It included a solar year of 365 days and a sacred year of 260 days. An almanac gave dates for fixed and movable religious festivals and listed the various gods who held sway over each day and hour. The Aztec had hieroglyphics and number symbols with which they recorded religious events and historic annals.

Religion was a powerful force in Aztec life. The Aztec worshipped a host of all-powerful gods. Some gods personified the forces of nature, such as the sun and the rain. Others were associated with basic human activities, such as war, reproduction, and agriculture. There were also gods of craft groups, social classes, and governments.

The Aztec perform a round dance for Quetzalcóatl and Xolotl (a dog-headed god who is Quetzalcóatl’s companion). The illustration comes from a reproduction of the Codex Borbonicus, an Aztec manuscript. Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Chicago

To obtain the gods’ aid, worshippers performed penances and took part in innumerable elaborate rituals and ceremonies. Each god had one or more special ceremonies, in which offerings and sacrifices were made to gain the god’s favor. Human sacrifice played an important part in the rites. Because life was humankind’s most precious possession, the Aztec reasoned, it was the most acceptable gift for the gods. As the Aztec Empire grew powerful, more and more sacrifices were needed to keep the favor of the gods. Records indicate that 20,000 captives taken in battle were killed at the dedication of the great pyramid temple in Tenochtitlán. They were led up the steps of the high pyramid to the altar, where chiefs and priests took turns at slitting open their bodies and tearing out their hearts.

An Aztec priest performs a sacrificial offering of a living human heart to the war god Huitzilopochtli. The illustration comes from a reproduction of an Aztec manuscript called the Codex Magliabecchi. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (neg. no. LC-USZC4-743)

The Aztec Empire was at the height of its power when the Spanish arrived in 1519. The ninth emperor, Montezuma II (reigned 1502–20), was taken prisoner by Hernando Cortez and died in custody. His successors, Cuitláhuac and Cuauhtémoc, were unable to stave off Cortez and his forces. With the Spanish capture of Tenochtitlán in 1521, the Aztec Empire came to an end.