Civilizations began to develop in the central Andes Mountains of South America by approximately 2300 BC. For several thousand years they became increasingly elaborate, both culturally and technologically. By about AD 1000 these peoples were organized into a number of kingdoms, including Tiwanaku and Chimú. The Inca civilization was formed later and thrived until the Spanish invasion of the early 1500s.

The main ruins of the kingdom of Tiwanaku are located near the southern shore of Lake Titicaca in what is now Bolivia. Scholars believe that much of the site dates from about AD 200–600, though construction continued until about 1000. During the height of its power, Tiwanaku dominated or influenced large portions of what are now eastern and southern Bolivia, northwestern Argentina, northern Chile, and southern Peru.

A relief sculpture on the Gateway of the Sun at Tiwanaku depicts the Doorway God and accompanying “angels.” Georg Gerster—Rapho/Photo Researchers

Although archaeologists once thought Tiwanaku was mainly a ceremonial site, new finds in the late 20th century revealed that it was a bustling city. Among the main buildings is the Akapana Pyramid, a huge platform mound or stepped pyramid. The Kalasasaya is a low rectangular platform enclosed by alternating tall stone columns and smaller rectangular blocks. A notable feature of the Kalasasaya is the monolithic Gateway of the Sun, which is adorned with the carved central figure of a staff-carrying Doorway God as well as other smaller, winged figures that are sometimes called angels. Another feature of the site is a number of large and finely finished stone blocks with niches, doorways, and recessed geometric decorations. Tiwanaku pottery was painted with black, white, and light red representations of pumas, condors, and other creatures on a dark red background.

The influence of Tiwanaku was largely a result of its remarkable agricultural system. This farming method, known as the raised-field system, consisted of raised planting surfaces separated by small irrigation ditches, or canals. This system was designed in such a way that the canals retained the heat of the intense sunlight during frosty nights and thus kept the crops from freezing.

The Tiwanaku culture vanished by 1200. Scholars have speculated that the present-day Aymara Indians of highland Bolivia are descended from the people of Tiwanaku.

The Chimú kingdom originated in northern Peru in about AD 1000 and expanded southward, overlapping the northern territory of Tiwanaku as that kingdom’s influence began to decline. Chimú grew into a powerful kingdom in the 1300s and for two centuries reigned as the chief state in Peru.

The ruins of Chan Chan, Peru, include fascinating examples of adobe mud streets, reservoirs, and walls. Shutterstock.com

Chimú was ruled from the city of Chan Chan, on Peru’s northern coast. Chan Chan is one of the world’s most notable archaeological sites, with 14 square miles (36 square kilometers) of ruins. Among them are rectangular blocks and streets, great walls, reservoirs, and pyramid temples, all built of adobe mud. Chan Chan’s population must have numbered many thousands.

Chimú culture was based on farming, which was aided by immense irrigation works. The Chimú seem to have had an elaborate system of social classes ranging from peasants to nobles. They produced fine textiles and gold, silver, and copper objects. They also made pottery in standardized types, which they produced in quantity using molds. The Chimú spoke Yunca (also called Yunga or Moche), a now-extinct language, but had no writing system.

Between 1465 and 1470 the Chimú were conquered by the Inca. The Inca absorbed much from Chimú culture, including their political organization, irrigation systems, and road engineering.

When the Spanish reached Peru in 1532, they encountered the vast empire of the Inca. The great civilization of the Inca extended along the Pacific coast of South America from modern Ecuador southward to central Chile and inland across the Andes. The Inca had conquered this huge territory in a single century, and they ruled its people through a highly organized government. At the peak of their power the Inca ruled some 12 million people of more than 100 ethnic groups. Most of the people eventually spoke Quechua, the Inca language, at least as a second language.

The Inca civilization flourished because intensive agriculture provided an ample food supply. The Inca achieved this despite harsh growing conditions such as frost on most nights of the year in the highlands. In areas with steeply sloping terrain, they built stone terraces to increase the amount of flat land for crops. Inca farmers raised corn, beans, squash, potatoes, quinoa, sweet potatoes, cassava, peanuts, cotton, peppers, tobacco, coca, and dozens of other plants. They developed thousands of varieties of their crops to suit different growing conditions. For example, they raised certain kinds of tubers and grains that thrived at high altitudes.

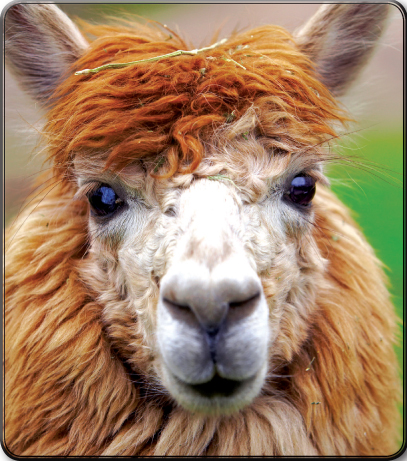

Domesticated alpacas provided the Inca with wool and carried heavy loads. Allan Baxter/Photographer’s Choice RF/Getty Images

The Inca also domesticated llamas and alpacas. They raised vast herds of these animals to carry loads and to supply wool and sometimes meat. They also raised guinea pigs for meat.

Inca villages first developed in coastal valleys where water was available for irrigation. Settlements then spread to the high Andean plateau, where some grew into cities. The largest city was Cuzco, the Inca political and religious capital. It had tens of thousands of inhabitants, perhaps as many as 200,000. (By comparison, London, England, had a population of more than 100,000 in 1550.) Most Inca settlements were small villages, however, home to a few hundred people.

The Inca reserved their most remarkable architecture for public buildings. They built massive stone palaces, temples, and fortresses without the use of mortar. Some of the walls still stand. They cut the stones precisely, fitting them so tightly that not even a knife blade can be inserted into most seams.

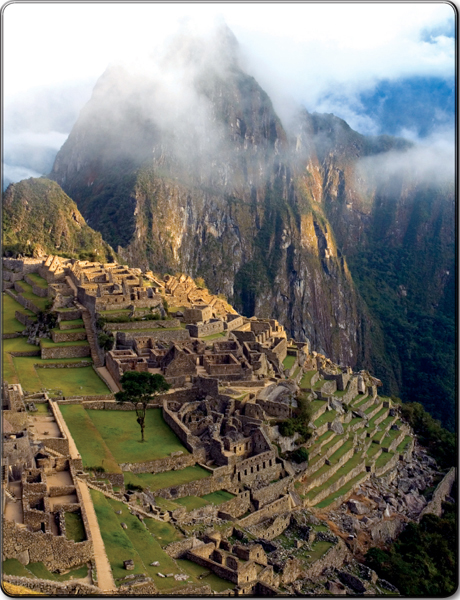

Machu Picchu ruins. Linda Whitwam/Dorling Kindersley/Getty Images

The most famous Inca ruins today lie to the northwest of Cuzco at Machu Picchu, perched on steeply sloping land between two sharp peaks. Its numerous white granite structures include temples and other ceremonial sites, palaces, and small houses at various levels connected by stone staircases. Surrounding the residential area are hundreds of well-built stone terraces for farming that were once watered by an aqueduct system.

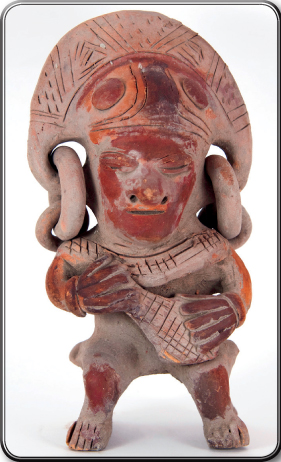

The Inca placed a high value on craftsmanship. Their technology differed little from that of surrounding areas, but their products were exceptional for their quality and variety. The most outstanding items were made for the government and the nobility by highly skilled artisans.

Notable crafts of the Inca included metalworking, pottery making, and weaving. In addition to gold and silver ornaments, metalworkers made knives, axes, chisels, needles, and other tools from copper and bronze. Potters produced both everyday wares and fine ceremonial pieces for religious uses. Weaving was the most important art. Inca weavers made not only clothing but also colorful textiles and tapestries, often with complicated patterns.

A warrior figure is an example of Inca pottery. iStockphoto/Thinkstock

The Inca built an extensive network of roads throughout the empire. The two main royal highways ran north–south, one along the coast and the other across the mountains. Each was about 2,250 miles (3,600 kilometers) long. Many other roads linked the two main highways. The system also included short rock tunnels and suspension bridges supported by woven cables. Only people on official state business were supposed to use the highways.

Inca society was highly stratified, with people occupying various social ranks by birth. At the top of society was the emperor. Considered a child of the sun, the emperor ruled by divine right and had absolute authority. Below him were all those who were ethnically Inca. These Inca nobles filled all the most important positions in government, the military, and the state religion. Some important posts were filled with people considered to be “Inca by privilege.” People granted this status were generally from loyal non-Inca groups of the Cuzco valley. Below them were the various local chiefs and lords. Finally, the bulk of the people were commoners, most of whom made a living by farming or herding animals.

The Inca created a highly organized state religion based on the worship of their sun god, Inti. The Inca believed Inti was their divine ancestor. The Inca also worshipped the Andean god Viracocha, creator of the universe, the other gods, and people and animals.

In the name of their gods, the Inca took control of new lands and spread their religion. As they expanded their territory, they incorporated some of the major local gods into the state religion. The Inca allowed the various groups within the empire to continue practicing their own religions, as long as they also worshipped Inti. They also had to farm the land and raise the herds that provided Inti and his priests with food and cloth.

On every important occasion, the Inca made sacrifices to the gods of valued items such as food, chicha (a beer made from corn), fine cloth, coca leaves, guinea pigs, and llamas. When a new emperor took office and in times of extreme need—such as great famine, disease, and defeats in battle—the Inca sacrificed humans. The victims were children who were considered physically perfect.

In 1531 Francisco Pizarro, a Spanish adventurer, led an expedition into Inca territory. Finding the empire divided by a recent civil war over the throne, Pizarro captured Atahuallpa, the Inca emperor, in 1532 and had him executed. By 1535 the empire was lost. However, Quechuan-speaking Indians descended from the Inca still remain the dominant native language group in the central Andes.

Francisco Pizarro. Hulton Archive/Getty Images