In Northern America the transition from an Archaic way of life based mainly on hunting and gathering to one more dependent on agriculture took longer than it did in Middle and South America. Prehistoric farming peoples of Northern America shared certain similarities. They lived more settled lives than Archaic groups, though most still did some hunting away from their settlements. They often protected their communities with walls or ditches. And many farming peoples developed hierarchical societies in which a class of priests or chiefs had authority over one or more classes of commoners.

In the first centuries AD three major farming cultures arose in the Southwest: the Ancestral Pueblo (also known as the Anasazi), the Mogollon, and the Hohokam. All had cultural connections to the earlier Cochise culture. By about 1200 BC, Indians of the Southwest had begun to grow corn and squash. But they could not produce reliable harvests until they overcame the region’s dryness using irrigation.

In the first centuries AD, three major farming cultures arose in southwestern North America: the Ancestral Pueblo, the Mogollon, and the Hohokam. Each of these cultures reached its height between about AD 700 and 1300.

The Ancestral Pueblo lived on the plateau where the U.S. states of Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah now meet. Their culture began in about AD 100. At first these people combined hunting, gathering wild plant foods, and some corn cultivation. They typically lived in caves or in shallow pit houses—structures of poles and earth built over underground pits. They also created pits in the ground that were used for food storage.

As farming became more important, the Ancestral Pueblo built irrigation structures such as reservoirs and check dams—low stone walls used to catch runoff from the limited rains. Hunting and gathering became secondary to farming, and the Ancestral Pueblo adopted a more settled lifestyle. Originally, they built partly underground houses in caves or on the tops of high, rocky plateaus called mesas. Later they built above-ground dwellings, both on mesas and in canyons. Using stone masonry they constructed a number of large communities, some with more than 100 adjoining rooms. Kivas—underground circular chambers used mainly for ceremonial purposes—became important community features. Pottery came into widespread use.

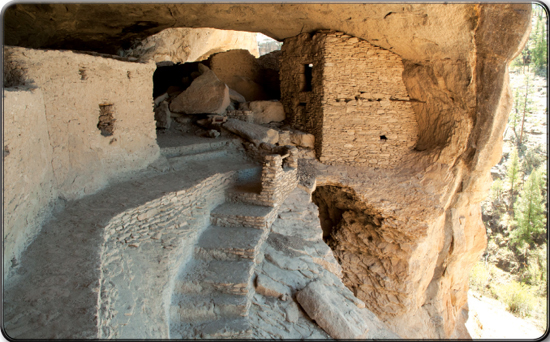

The Cliff Palace, an Ancestral Pueblo dwelling in Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, has 150 residential rooms and several towers. © C. McIntyre—PhotoLink/Getty Images

The architecture of the Ancestral Pueblo culminated with the cliff dwellings. Built between 1150 and 1300, these massive houses were set along the sides or under the overhangs of cliffs. Large, apartment-like structures were also built along canyons or mesa walls. The population became concentrated in these large communities, and many smaller villages and hamlets were abandoned. Agriculture continued to be the main economic activity, and craftsmanship in pottery and weaving achieved its finest quality during this period.

The Ancestral Pueblo abandoned their communities by about 1300. A drought lasting from 1276 to 1299 probably caused massive crop failure. At the same time, conflicts increased between the Ancestral Pueblo and neighboring groups that may have been the predecessors of the modern Navajo and Apache peoples. The Ancestral Pueblo moved to the south and the east, near better water sources. The descendants of the Ancestral Pueblo make up the modern Pueblo Indian tribes.

The Mogollon culture existed from about AD 200 to 1450. The homeland of the Mogollon Indians was the mountainous region of what are now southeastern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico. Their territory also extended southward into what are now the Mexican states of Chihuahua and Sonora.

The Mogollon obtained most of their food by hunting and by gathering wild seeds, roots, and nuts. At first they hunted mostly small prey, such as rabbits and lizards, that could be caught in nets or snares. Later they hunted deer and other larger game. Because the Mogollon lived in the mountains, much of their land was not good for growing crops. But they eventually began to grow corn, squash, and beans. They used small dams to pool rainfall and divert streams for watering crops.

At first the Mogollon lived in small villages of pit houses grouped near a large ceremonial structure. Early pit houses were circular with a ceiling made of wood covered with mud. The entrance was through a tunnel. Later pit houses were rectangular and made of stone. Between about 650 and 850 the Mogollon began to build larger pit structures to serve as ceremonial kivas. The appearance of these structures suggests the influence of the Ancestral Pueblo.

By about 1000 the Mogollon began to replace their pit houses with adobe and stone apartment-style houses like those of the Ancestral Pueblo. These houses were built at ground level and rose one to three stories high. These villages sometimes contained 40 to 50 rooms arranged around a plaza. Evidence from this period suggests that Ancestral Pueblo and Mogollon peoples lived peacefully in the same villages.

Gila Cliff Dwellings National Monument, New Mexico. The Mogollon gradually began to build apartment-style houses that rose up to three stories high. Shutterstock.com

The Mogollon made the first pottery in the Southwest. At first the pottery was simple, made of red or brown clay and undecorated. Over time the Mogollon included designs on the pots and other vessels. They also learned to make and use paints. The Mimbres were a group of Mogollon who were especially well known for their pottery. It was decorated with imaginative black-on-white designs of insects, animals, and birds or with geometric lines.

The Mogollon culture ended for unknown reasons in the 15th century. The people abandoned their villages, perhaps spreading out over the landscape or joining other village groups.

Between about AD 200 and 1400 the Hohokam people developed an advanced farming culture along the Salt and Gila rivers in southern Arizona. The Hohokam depended on farming for most of their food. They grew corn and eventually beans and squash. They supplemented their food supply by hunting and gathering wild beans and fruits. Another important crop was cotton, which they used to make cloth.

The Hohokam are famous for their complex network of irrigation canals, which was unsurpassed in prehistoric Northern America. The canals, some as long as 10 miles (16 kilometers), rerouted the Gila and Salt rivers to water the fields. They may have been built by cooperating villages. Some of the more than 150 miles (240 kilometers) of canals in the Salt River valley were renovated and put back into use in the 20th century.

Hohokam irrigation canals were more complex than those of any other prehistoric culture north of Mexico. Morey Milbradt/Brand X Pictures/Getty Images

The early Hohokam lived in villages of widely scattered pit houses made of wood, brush, and mud. After about 775 they built large ball courts, similar to those of the Maya of Mexico, and after 975 enclosed some of their villages with walls. After 1150 the Hohokam learned from their Ancestral Pueblo neighbors to construct multistoried community houses with massive walls of adobe. Some houses were built on top of platform mounds.

The Hohokam were active traders. From Mexican peoples they obtained such goods as rubber balls, copper bells, turquoise, obsidian, and macaws, which they kept as house pets. The Hohokam obtained shells from Indians living near the Gulf of California and the Pacific coast. They etched decorations into the surfaces of these shells with acid, becoming the first people in the world to use this artistic technique. Shell jewelry made by the Hohokam was a valuable trade item. They also made baskets and several kinds of pottery.

The Hohokam people abandoned most of their settlements between 1350 and 1450. It is thought that the drought of the late 1200s, combined with a subsequent period of sparse rainfall, contributed to this process. The Pima and the Tohono O’odham (Papago) peoples are modern descendants of the Hohokam.

Over the centuries Archaic Indians east of the Mississippi River had learned to cultivate such plants as sunflowers, squash, and sumpweed. By about 500 BC, the production of these plants had become the basis of the Adena culture. Later came the Hopewell and Mississippian cultures.

The Adena culture occupied what is now southern Ohio and lasted from about 500 BC to AD 100, though in some areas it may have started as early as 1000 BC. The Adena were mainly hunters and gatherers, but they also did some farming. They seem to have raised sunflowers, squash, and some other food plants, as well as tobacco for ceremonial purposes. The Adena usually lived in villages of cone-shaped houses. The houses were built by setting poles into the ground, connecting them with grass or branches, and covering the structure with mud. Some Adena lived in rock shelters. Artifacts from Adena sites include stone tools, simple pottery, and beads, bracelets, and other ornaments made from shells and copper obtained through trade.

Early North American farmers east of the Mississippi River are known as Eastern Woodland, and later as Mississippian, peoples. The Adena culture lasted from about 500 BC to AD 100, the Hopewell culture from 200 BC to AD 500, and the Mississippian culture from AD 700 to 1500.

The most distinctive element of Adena culture was mound building. They buried their dead in large earthen mounds, some of which were hundreds of feet long. They also built great earthworks in the shape of animals. These are called effigy mounds. The mounds were built by heaping up basketful after basketful of earth. Some of these large mounds still exist.

The farming culture of the Hopewell Indians lasted from about 200 BC to AD 500, mainly in southern Ohio. Like the Adena, the Hopewell built elaborate earthworks for burial and other purposes.

Hopewell villages lay along rivers and streams. Houses consisted of pole frames covered with bark, animal hides, or woven mats. The people raised corn and possibly beans and squash but still relied upon hunting and fishing and the gathering of wild nuts, fruits, seeds, and roots. Expert artists and craftsmen made carved stone pipes, a variety of pottery, and spear points, knives, axes, and other tools of flint and obsidian. They also made various ceremonial objects out of copper. The Hopewell traded widely. Material from as far away as the Rocky Mountains and the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean has been found in Hopewell sites.

Hopewell Culture National Historical Park in south-central Ohio preserves some of the prehistoric burial mounds made by the Hopewell people. © Hilit Kravitz

Some Hopewell mounds appear to have been used for defensive purposes, but more often they served as a place to bury the dead. Some formed the bases of temples or other structures. The size of the mounds at many sites—up to about 30 feet (9 meters) high—has led scholars to believe that communities probably worked together to create them. The people likely labored under the direction of a powerful leader.

The last great prehistoric culture in what is now the United States was the Mississippian. Beginning in about AD 700 it spread throughout the Southeast and much of the Northeast. The Mississippian culture was based mainly on the production of corn.

The people lived in large towns governed by priest-rulers. Each town had one or more huge, flat-topped mounds that supported temples or the houses of rulers. These mounds often rose to a height of several stories. They were generally set around a plaza that served as the community’s ceremonial and social center. The largest Mississippian town was at Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis, Mo. At its peak, it housed 10,000 to 20,000 people. The site originally consisted of about 120 mounds spread over 6 square miles (16 square kilometers), but some of the mounds and other ancient features have been destroyed. Monk’s Mound, the largest mound at Cahokia, is about 1,000 feet (300 meters) long, 700 feet (200 meters) wide, and 100 feet (30 meters) high.

Mississippian peoples were united by a common religion focusing on worship of the Sun and a variety of ancestral figures. An organized priesthood conducted elaborate religious rituals and probably also controlled the distribution of surplus food and other goods. Fine craftwork in copper, shell, stone, wood, and clay often displayed religious symbols. The elaborate designs included feathered serpents, winged warriors, spiders, human faces with weeping or falcon eyes, as well as human figures and many geometric motifs. These elements were delicately engraved, embossed, carved, and molded.

Mississippian people in the Southeast were among those who met the first European explorers. Some Mississippian groups, such as the Natchez, have maintained their ethnic identities into the 21st century.

Prehistoric farmers of the Great Plains are known as Plains Woodland and then Plains Village peoples. In this region Archaic peoples dominated until about AD 1, when ideas and perhaps people from Eastern Woodland cultures arrived. Between that time and about AD 1000, Indians of Plains Woodland cultures settled in small villages along rivers and streams. They raised corn, beans, and eventually sunflowers, gourds, squash, and tobacco.

Around AD 1000 Plains peoples began to combine their small villages to form larger settlements. The riverbanks became more densely settled. Thus began the Plains Village period, which lasted until about 1450. Like the Mississippian peoples, these cultures developed elaborate rituals and religious practices. The descendants of the Plains Village groups include such tribes as the Arikara, Mandan, Hidatsa, Crow, and Pawnee.