Chapter 4

SUPERSTARDOM, RUMOURS, AND TUSK

1975–1979

At the beginning of 1975, Fleetwood Mac was not just in one of their many ongoing states of flux. The band’s survival was in question.

Their guitarist, who’d written and sung much of the material on their last few albums, had just quit. An American tour by a bogus version of the band had wreaked havoc on their reputation, endangering their very right to use the name Fleetwood Mac. Even after the legal dust settled, it wasn’t certain whether the now-all-British trio could remain in the US, where they had yet to obtain green cards. As if he didn’t have enough to deal with, Mick Fleetwood was now managing the band, on top of trying to keep both the group and his wavering marriage together.

Reprise Records at least had faith in the act, renegotiating their deal with the band shortly before Bob Welch’s departure. Yet as many good reviews as their LPs had received, and as much FM airplay as some of their album cuts had generated, Reprise couldn’t be expected to hang on forever. Fleetwood Mac had yet to dent the Top 30 of the US album or singles charts and badly needed a hit. Their saviors would be stumbled upon by sheer luck.

Stevie Nicks at the Yale Coliseum in New Haven, Connecticut, on November 20, 1975. With her top hats, black chiffon dresses, and hit compositions, Nicks quickly became the most popular member of Fleetwood Mac. Getty Images

Mick Fleetwood at the twentieth Grammy Awards at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, February 23, 1978. Rumours won a Grammy for Album of the Year at the event. Getty Images

Even before Welch left, Fleetwood was scouting Los Angeles for the right studio to record their next album. While shopping for groceries at the fabled Laurel Canyon Country Store in November 1974, he ran across an acquaintance, Thomas Christian, who urged him to check out a facility in the nearby San Fernando Valley. Fleetwood drove directly from there—groceries and kids still in the back seat—to Sound City, where engineer Keith Olsen played him a demo of sorts of recent sounds cut on the premises. The tape was “Frozen Love,” by a little-known duo who had released just one obscure LP, was working on another, and had no intention of joining a different band.

Although they were also young veterans of the music business who’d begun performing in the 1960s, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks could in some ways have hardly been more different from Mick Fleetwood, John McVie, and Christine McVie. They were as Californian as Fleetwood and the McVies were British. With their arrival in Fleetwood Mac, the band’s gradual, nearly decade-long transformation from pure blues to pure pop would be complete. The entry of Buckingham and Nicks would also more dramatically change the music and fortunes of Fleetwood Mac than any personnel shift undergone by any major band.

Born on October 3, 1949, and raised near Palo Alto, California, about thirty miles south of San Francisco, Lindsey Buckingham had a more comfortable upbringing than his future British bandmates. Like now-long-ago Mac guitarist Jeremy Spencer, he was a fan of early rock ’n’ rollers, citing Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers, Chuck Berry, and Eddie Cochran as heroes. But he also enjoyed folk and bluegrass, and became proficient on acoustic guitar—a skill that would prove invaluable in Fleetwood Mac—before developing his electric guitar chops.

Lindsey’s older brother Greg won a silver medal in swimming at the 1968 Olympics, about a year after Lindsey joined his first pro outfit, Fritz. Unlike the original members of Fleetwood Mac, his rise to the top of his profession would be slow and labored. In Fritz, he wasn’t even playing guitar, handling bass duties. But Fritz did give him an opportunity to play gigs for years around the San Francisco Bay Area. More crucially, it was also where he first worked closely with their singer, Stevie Nicks.

Born May 26, 1948, in Phoenix, Nicks grew up in several states as her father established himself as a successful business executive, at one time holding the presidency of Greyhound’s Armour-Dial subsidiary. If she inherited some of his ambition, her musical aptitude was triggered by learning to sing with her grandfather, country singer Aaron Jess Nicks. After singing in a Los Angeles high school group called the Changing Times, she moved to Northern California and attended Menlo-Atherton High School. Buckingham was a grade behind her, and at a church meeting they sang the Mamas & the Papas’ “California Dreamin’” together, leading to Lindsey’s invitation for her to join a proper band.

After dropping out of San Jose State University (which Buckingham also attended for a while), Nicks hooked up with Fritz, who opened for several major acts at Bay Area venues, including Santana, Jimi Hendrix, and early idol Janis Joplin. Within the band’s three-and-four-part harmonies, Buckingham and Nicks got used to singing together, Buckingham sometimes (unusual for a male vocalist) taking the higher harmony than Nicks. Stevie also had some time in the lead vocal spotlight, acting out drug withdrawal pains on their cover of Buffy Sainte-Marie’s “Codeine.”

But while Fritz performed original material on the concert circuit for years, they never got as far as making a record before breaking up in the early 1970s. They hardly performed any songs by Buckingham or Nicks, although Nicks had been writing since she was a teenager. And while some of their most memorable material would be fueled by their romantic ups and downs, they weren’t in a relationship while they were in Fritz.

Fritz’s split gave the pair a chance to continue as both a musical and personal duo, now focusing on their original compositions. Plans to move to Los Angeles were delayed for almost a year while Buckingham recovered from a serious bout with mononucleosis. Buckingham used the downtime to his advantage, however, improving his electric guitar technique and working on some demos with Nicks.

Unreleased demos from this period that have made it into circulation find them still very much in search of a style, and pretty far from the style for which they’d become renowned. A batch often dubbed “The Coffee Plant Demos” (after the coffee plant owned by Buckingham’s father, in whose basement the pair made tapes) is quite folky in nature. Nicks takes all the lead vocals, with only occasional vocal assistance from Buckingham, who also supplies acoustic guitar and bass. These and other early Nicks demos floating around find her in thrall to the mellow singer-songwriter style of the time, with echoes of James Taylor, Melanie, and Carole King. “Cathouse Blues” even sounds rather like Maria Muldaur’s brand of sassy folk-blues.

Stevie Nicks with a dog friend, 1975. Getty Images

Contact sheet featuring shots of every member of Fleetwood Mac in action in New Haven, Connecticut, 1975. Getty Images

There was little to make these baby steps stand out from the pack other than Nicks’ already distinctive, slightly husky vibrato vocals. There was still enough promise in what they were doing to make a crucial industry connection who would be vital to launching the careers of both Buckingham-Nicks and the revitalized Fleetwood Mac. With the help of engineer/budding producer friend Keith Olsen—who’d checked out Fritz, but quickly decided he only wanted to work with Buckingham and Nicks—they found a deal with the small Anthem label. The pair was set to record their debut in London’s Trident Studios before Anthem went under, almost stopping their recording career before it got started.

One of Anthem’s ex-owners, Lee LaSaffe, was nonetheless able to get them a deal with the major label Polydor, who issued the plainly titled Buckingham Nicks LP in September 1973. Produced by Olsen—with top LA session musicians such as guitarist Waddy Wachtel, Elvis Presley bassist Jerry Scheff, and drummer Jim Keltner in the support cast—it was almost wholly ignored by both critics and record buyers. The odd exception was Birmingham, Alabama, where the LP somehow gained an avid audience. They would play a Birmingham gig before a sellout crowd of seven thousand fans, although by that time, they’d already accepted an invitation to join a much bigger act.

It’s easy to hear seeds of Buckingham and Nicks’ contributions to Fleetwood Mac in Buckingham Nicks. Buckingham and Nicks wrote all but one of the tracks (usually separately), which boast the crafty blends of acoustic and electric guitars that would become a Buckingham trademark. The two were also adept at weaving harmonies and different vocal parts together, both having developed into capable lead singers.

“Wish you could be here to hear some of this stuff,” Nicks enthused in a letter to her family as she and Buckingham immersed themselves in sessions at Sound City. “Lindsey may go down in history as one of the greats in guitar-playing. It really is quite amazing.” Yet even at this early juncture, there was a distinct difference between the compositions of Nicks and those of Buckingham, the writers who would soon pen the majority of Fleetwood Mac’s original material. As Olsen put it in the documentary Stevie Nicks Through the Looking Glass, “The Stevie Nicks songs had that little bit of folky lightness, and Lindsey’s material had this deeper sense of feel.”

The mildly controversial cover of the sole Buckingham Nicks LP, released in September 1973.

Yet it’s also easy to hear why the album failed to make a commercial impact. While much of the template for their work in Fleetwood Mac was in place, the songs simply weren’t all that memorable, blending into the also-ran woodwork of many similar early-1970s mainstream rock acts. Only one of the songs, “Crystal,” would be re-recorded by their subsequent band. Adding to the impression that they’d rather sweep the album under the rug, the record has never been issued on CD. They might also be embarrassed by the very of-its-time cover, for which Nicks was, to her dismay, asked to take off her blouse so the pair could pose bare-chested, her breasts just about hidden by an almost unrecognizably long-haired Buckingham. “Our record company had no idea what to do with us,” he complained in Rolling Stone. “They said something about wanting us to be the new Jim Stafford [then hot with the country-pop novelty hits ‘Spiders & Snakes’ and ‘My Girl Bill’], and they wanted us to play steakhouses.”

When Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham joined Fleetwood Mac in 1975, they gave the band two dynamic but distinctly different songwriters and performers in their front line. Getty Images

Billboard magazine, which called Buckingham-Nicks “a lackluster male-female acoustic duo” in a November 1973 review of their set at LA’s Troubadour club, found “both problems and promise in a brief but telling set” in New York the following March. “Chief virtues for the band are the strong vocal punch,” the publication surmised. “Buckingham currently handles both vocal leads and lead guitar, a role that seems to be a bit taxing. Ms. Nicks also encounters problems, chiefly in her solo style, which points up to the occasional roughness of her voice and the strident quality to her top end that makes duets bracing, but proves less than fruitful when she takes the stage alone.” Both would soon be able to rely on others to help carry the load, though as far as they knew in 1974, they’d have to make it or break it by themselves.

With no hit on their hands outside Alabama, Polydor dropped Buckingham-Nicks. Now label-less, Buckingham had to pick up session work to keep going, also touring as part of Don Everly’s backup band. Nicks worked as a Hollywood waitress, and had cleaned Olsen’s home for cash when funds were especially low. At other low points, Buckingham had even sold ads over the phone, resorting to writing bad checks for meals at Hollywood coffee shops. Nicks’ parents offered to support her, but only if she moved back to their home and went back to school—a deal that must have seemed tempting as the pair slid into near-poverty.

Mick Fleetwood at the Yale Coliseum in New Haven, Connecticut, on November 20, 1975. Even as Fleetwood Mac approached mainstream pop-rock superstardom, he never lost his taste for hamming it up when he could. Getty Images

But like the band whose path they’d soon cross, Buckingham and Nicks were persistent. They kept working on demos for a second album at Sound City—“it was like our home away from home,” observes Nicks in the Sound City documentary—even in the absence of a record contract. Olsen had enough faith in the duo to help get them free time at Sound City, where they recorded tracks with engineer Richard Dashut, in whose one-room apartment they lived for a while.

When Keith Olsen played Mick Fleetwood “Frozen Love” (which had concluded the Buckingham Nicks album) at Sound City, Fleetwood liked what he heard. As Buckingham and Nicks were working in a different part of the studio at the time, Fleetwood briefly saw the pair for the first time that same visit. “I met Lindsey literally in passing, and I went off not even thinking anything other than I’ve heard some good music that was made in the studio that I’m gonna use,” he admitted in the Sound City documentary.

Fleetwood booked time for Fleetwood Mac to cut their next album at Sound City in starting in early 1975, only for Bob Welch to quit shortly before the sessions were due to begin. A replacement was needed immediately if they were to keep to their schedule. On New Year’s Eve in 1974, Olsen relayed Fleetwood’s invitation for Buckingham and Nicks to join Fleetwood Mac, without so much as an audition. Fleetwood was mostly interested in adding Buckingham to the lineup, but it was made clear that if he joined, they’d have to take Nicks too.

It seemed like a no-brainer to make the leap from waiting tables and doing telephone sales to joining a famous if struggling band, but the decision wasn’t that simple. At first, Nicks and Buckingham were neither overjoyed nor entirely convinced it was the right career move. They had a great deal of faith in the material they were hoping to put on their second album, and not so eager to give up on the record at a moment’s notice. Common sense prevailed, however, and within a few weeks Buckingham and Nicks were rehearsing with Fleetwood Mac, bringing with them some of the songs they’d hoped to use for themselves.

Like so many bands in rock, on paper it was a combination that no one would have expected to work. Acts both mixing British and American musicians and men and women were rare enough to be unprecedented in rock’s upper echelon. Two couples within the same band was unprecedented in a rock group of significant stature, at least in such a public fashion. Fleetwood and the McVies had made their first hit records in the late 1960s; Buckingham and Nicks, though not much younger, had made just one record that hardly anyone had heard.

Yet somehow, they instantly clicked, both musically and personally. In early 1975, they began work on their first album together at Sound City, sharing production credits with Olsen. They wouldn’t even play their first concert together until May. Buckingham and Nicks completed their final obligations as a twosome early the same year with some concerts in Alabama.

Among the songs they performed in their final shows were several that would be included on the new Fleetwood Mac album, Fleetwood Mac (not to be confused with their 1968 UK debut LP, also often referred to as Fleetwood Mac, though its official title was Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac). While not exactly dominating the proceedings, Nicks and Buckingham were immediate central forces in the new lineup, writing and singing more than half of the material. The vocals and compositions were now split among Nicks, Buckingham, and Christine McVie, giving the new Fleetwood Mac an unusually strong concentration of singer-songwriter talent within one ensemble.

“It was like taking over two-thirds of the writing duties in the band,” remarked Buckingham in a 1977 interview with John Pidgeon that’s archived on the Rock’s Backpages website. “And that in itself is gonna change the sound.” But as he pointed out, “They’ve always been very fair with allowing everyone to be creative and to have a good vehicle for output.”

John McVie in New Haven, Connecticut, 1975. It wasn’t made public until the following year, but his marriage to Christine McVie was coming to an end around this time. Getty Images

Christine McVie didn’t attract as much attention as the two other principal singer-songwriters in Fleetwood Mac, Nicks and Buckingham, after they joined. But she was just as vital to their most popular albums, penning the hits “Over My Head,” “Say You Love Me,” “You Make Loving Fun,” and “Don’t Stop.” Getty Images

At her first rehearsal with Nicks and Buckingham, stated Christine McVie in Fleetwood’s first autobiography, “I started playing ‘Say You Love Me,’ and when I reached the chorus they started singing with me and fell right into it. I heard this incredible sound—our three voices—and said to myself, ‘Is this me singing?’ I couldn’t believe how great this three-voice harmony was. My skin turned to gooseflesh and I wondered how long this feeling was going to last.”

This didn’t mean that the second longest-serving member of the band didn’t have his reservations. “John McVie said to me, ‘You know, we’re a blues band. This is really far away from the blues,’” remembered Olsen with amusement in the Sound City documentary. “And I said, ‘I know. But it’s a lot closer to the bank.’” And as John colorfully put it in Sam Graham’s Before the Beginning: A Personal & Opinionated History of Fleetwood Mac, “It seems the time was right for a rock band with two girl singers—a real rock band, not like ABBA or the New Seekers, where the girls act as if they’ve never seen a tampon in their lives.”

From the first lines of Fleetwood Mac’s opening cut “Monday Morning,” it was evident that this was not only a new Fleetwood Mac, but a new Buckingham and Nicks. Written and sung by Buckingham, it was far catchier than anything on Buckingham Nicks, and more upbeat and poppier than anything Fleetwood Mac had previously cut, especially when it burst into an exultant chorus. The slightly spaced-out mysticism that Nicks would make her forte came to the fore on another of the album’s highlights, “Rhiannon,” which likewise revolved around a chorus with more of a hook than anything on her LP with Buckingham. Shortly before joining the band, Nicks had come across a Rhiannon character in Mary Leader’s novel Triad, “just fell in love with the name, sat down, and wrote the song in about ten minutes,” she told Sounds. “Her Rhiannon is evil and mine is really good.”

“There’s always been a very mystical thing about Fleetwood Mac,” she asserted five years later in Trouser Press. “When I first joined Fleetwood Mac I went out and bought all the albums—actually, I think I had asked Mick for them because I couldn’t possibly afford to buy them—and I sat in my room and listened to all of them to try to figure out if I could capture any theme or anything. What I came up with was the word ‘mystical.’ There is something mystical that went all the way from Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac straight through Jeremy, through all of them: Bob Welch, Christine, Mick, and John. It didn’t matter who was in the band; it was always just there. Since I have a deep love of the mystical, this appealed to me. I thought this might really be the band for me because they are mystical, they play wonderful rock ’n’ roll and there’s another lady so I’ll have a pal.”

Maybe the sudden presence of two new kids on the block helped raise Christine McVie’s game, as she too came up with more accessible tunes than she’d ever performed on her previous recordings. If more low-key than the brasher songs by Buckingham and Nicks, “Over My Head” and “Say You Love Me” oozed a breathy, insinuating romanticism. While McVie had sung (and played piano on) more-than-respectable blues- and soul-influenced rock going back to her days with Chicken Shack, it was not until Buckingham and Nicks shared the stage that she really bloomed as a highly commercial pop-rock composer. “I had a lot to prove,” she conceded in David Wild’s liner notes to the 2013 expanded version of Rumours. “I was in awe of Stevie and Lindsey, and felt a great urgency to write some songs that surpassed others I’d written in the past.”

And with Nicks on board, Fleetwood Mac had two woman singers projecting sultry sexiness, though their differences also worked to their advantage. “Christine has a real drawn, deep voice, it’s like velvet,” remarked Olsen in the documentary Stevie Nicks Through the Looking Glass. “And Stevie is this nasally thing that is almost on the verge of being a goat. And so you put the two together, and you get something that is really unique.”

In sum, as Ben Edmonds wrote in his review of the Fleetwood Mac album for Phonograph Record Magazine, the album Buckingham and Nicks had done on their own “sounds absolutely premature by comparison with their initial accomplishments as a part of Fleetwood Mac. They’re both talented writers and singers, but their decisive contribution to the band is more in the realm of attitude; there’s an aggressive energy at work here that even the original Fleetwood Mac might not’ve been able to match.”

They also helped bring out some of Christine McVie’s strengths as an instrumentalist, Edmonds praising how “her keyboards mesh with Buckingham’s guitar to give the overall sound more punch, bringing a band that has always been the sum of readily identifiable parts into a more unified perspective. Far from being merely a good band with a distinguished past,” he concluded, “Fleetwood Mac is a band with a future. A record strong enough to demand immediate inclusion in any consideration of the year’s best.”

Fleetwood Mac was also a more radio-ready album than any the band had cut with different personnel. Olsen—a young veteran of the music business who’d played bass in the Music Machine (famed for the classic 1966 garage rock hit “Talk Talk”) and would go on to great success in productions with Rick Springfield, Pat Benatar, the Grateful Dead, and numerous others—might have gotten the producer gig because he worked with Buckingham and Nicks and introduced them to Fleetwood at Sound City. But he helped give the record a clean balance between different instruments; acoustic and electric guitars; and different singers, the band now using more vocal harmonies than ever.

A few months after fighting for their life, Fleetwood Mac had finished, somewhat to their surprise, the most commercial record they’d ever recorded. Now the task was to both sell it and popularize their new lineup to millions of listeners who had never heard of Buckingham and Nicks. Despite their half-dozen years of experience on the US concert circuit, it wasn’t going to be easy. Indeed, for all the eventual popularity of Fleetwood Mac—often referred to by fans and the band themselves as “The White Album,” in honor of its rather sparse cover design—it wouldn’t reach #1 until more than a year after its July 1975 release.

Part of the problem in making the LP a breakout hit was the very track record that had made Reprise such a staunch supporter of the band, even in the face of middling sales year after year. Their label was willing to keep them on, but hesitant to throw much promotion behind the new record and lineup. The company’s attitude changed little, even after Fleetwood met personally with Warner Brothers president Mo Ostin to plead the album’s case. When the company agreed to take out a full-page ad in Billboard, they mixed up the names of Buckingham and Nicks in the captions.

“We were an outfit that could be counted on consistently to move between 250,000 and 300,000 records whenever we put out an album, but that was about it,” muses Fleetwood in his second autobiography. “We never did better, we never did worse. Essentially, what we earned covered the expense of keeping us on the label and little more.” Reprise-Warners was also reluctant to give tour support to yet another version of Fleetwood Mac—the ninth or tenth version, depending on whether you count the brief period when Peter Green rejoined—that had yet to prove viable as a concert attraction.

That wasn’t going to stop Fleetwood Mac from taking the new lineup on the road, playing their first show in El Paso, Texas, on May 15, 1975. With “The White Album” two months shy of release, the band didn’t have a new record to promote or even a settled stage repertoire. For their first tour, they mixed a few songs from the upcoming LP—one of which, “Crystal,” had actually first appeared on Buckingham Nicks—with songs from records done before Buckingham and Nicks joined, some (like “Oh Well”) dating back to the Peter Green era. Playing midsize arenas, they were still often an opening act, sharing bills with such fading 1970s stars as Ten Years After, the Guess Who, and Loggins & Messina.

Yet in some ways, their very lack of a superstar track record might have ultimately worked to their benefit. Concertgoers and radio listeners with little or no familiarity with Macs of days gone by—which, in 1975, constituted the majority of young Americans—were open to appreciating Fleetwood Mac as something of a brand-new band, which in a sense they were, now that Nicks and Buckingham were in the ranks. The two also gave the band their most dynamic frontpeople since Green and Spencer had paced the boards in the late 1960s, with one important difference. Green and Spencer, for all their attributes, were not exactly sex symbols. With her fashionable shag haircut, colorfully eccentric wardrobe (soon to feature black chiffon dresses and top hat), and sensuous stage presence, Nicks was drawing legions of new fans who’d never have looked twice at photos of the Macs I, II, or III. “Gypsy” and “witch” were the usual labels pinned on Nicks, in part because she actually introduced “Rhiannon” as a song about a witch onstage.

It was quite an adjustment at first for a long-running band who had never featured a woman singer, even part of the time, who didn’t play one of the band’s core instruments (though Nicks did shake a tambourine onstage). “How dare this California bimbo—which is how they looked at me—come in and walk out into the center of our stage and be the lead singer overnight?” is how Nicks characterized their initial reaction on the BBC television program Rock Family Trees. But, she hastened to add, “They realized really quickly that I wasn’t trying to take anything away from them. And I wasn’t. And I really did love them and want them to be wonderful. And I certainly didn’t want to take anything away from Chris. ’Cause I liked her and I respected her, and she was really nice to me.”

Fleetwood Mac at the second annual Rock Music Awards on September 18, 1976. Although the two former couples within the band are locked in embraces, by this time the relationships were over. Getty Images

The more purely musical attributes of Nicks’ boyfriend garnered their share of critical praise too. “Buckingham is the best guitarist the group has ever had,” enthused Ken Barnes in a Phonograph Record Magazine review of a 1976 concert. “He gets a jangly folk-rock sound out of one guitar that some groups can’t get with three, and he’s got those driving power chords down cold.”

At the new Mac’s early shows, as Fleetwood told John Pidgeon, “Although all the halls weren’t necessarily full, the audience reaction was incredible. Because they’d never heard or seen Stevie and Lindsey within Fleetwood Mac, and there’s not one place or time where it got a little bit weird and… you know, ‘where’s Bob Welch’ and this, that, and the other. It was completely the opposite. So that again was a complete stroke for us. ’Cause we felt then completely confident being onstage.”

What really put the Fleetwood Mac album over the top, however, was the somewhat belated emergence of several hit singles, starting with “Over My Head.” Aided by a new mix designed specifically for AM stations and car radios, it cracked the Top 20 in early 1976. “Rhiannon”—which had quickly become a highlight of their concerts, and Nicks’ signature tune—made #11 a few months later. In the summer, a full year after the LP’s release, “Say You Love Me” began its own rise to #11.

Fleetwood Mac got flogged as “the great British-American-male-female-old-new-blues-rock-ballad band” in this ad for Fleetwood Mac (aka “The White Album”), their first LP with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks.

While these chart stats would be put to shame by the blockbusters that followed in the late 1970s, “The White Album” rode the coattails of these hits to the top of the album listings, though it took more than a year to do so. Ten years later, it was certified as having sold five million copies in the United States alone. But if 1976 and the Fleetwood Mac album sparked superstardom that ushered in some of the best of times for the band, in other ways, it was the worst of times for each and every one of them.

Stevie Nicks gripping the tambourine, her on-stage musical instrument. Getty Images

When Fleetwood Mac started to become a household name, it no doubt boosted their image to feature two married couples within the same band. As three of the four musicians in those couples were songwriters, it was easy for fans to fantasize that the songs were inspired by real-life romance. It was as if Fleetwood Mac were one big, happy extended family, and one that invited the audience to join in on the cozy fun.

By the time Fleetwood Mac became a hit, those relationships were ending or over. Some of their new songs would continue to be inspired by their partners/ex-partners, but the relationships they reflected weren’t always in full bloom, and weren’t always celebrated. Even their Rock-of-Gibraltar leader would divorce, remarry, and embark on a fling with Stevie Nicks.

One broken relationship has been all it takes to destroy many a band. Three at roughly the same time seemed to sound Fleetwood Mac’s death knell. Yet just as their love lives were imploding, their music was, almost perversely, thriving. Using their real-life traumas as grist for much of the material, Fleetwood Mac would somehow write and record their biggest commercial smash, and one of the highest-selling albums of all time.

It’s hard to map a precise chronology of who broke up when within Fleetwood Mac, as the bonds had been weakening for some time. Buckingham and Nicks might have been heading for a romantic separation (though not necessarily a professional one) even before joining the band. There’s even been speculation that they only stayed together as long as they did because it would have hurt Fleetwood Mac for the pair to break up just at the point when the new lineup was on the verge of a commercial and artistic breakthrough. The quick onset of success, if anything, quickened their split, the pressure of fame and constant touring overwhelming two musicians who’d struggled in the trenches for nearly a decade—and, unlike their three cohorts, had never experienced any degree of chart hits or critical recognition.

At the Glasgow Apollo in April 1977. Getty Images

Their rapidly growing audience remained oblivious to the tension for almost a year after Fleetwood Mac’s release. A brief news item in the April 22, 1976, Rolling Stone, however, made public what insiders had known for quite some time, dropping another big shoe in the process. “We hear that Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham are the second couple within Fleetwood Mac to be treading choppy waters,” reported the magazine. “Christine and John McVie split up eight months ago.” A two-page article on the band in the previous issue had not mentioned either of these bust-ups.

As the McVies had been married since August 1968, their breakup might have been a greater shock to longtime followers of the band. They’d lived and worked together for so long that it might have been taken for granted that they’d mastered the challenges of combining touring and recording with married life. Any hopes that fences could be mended took a blow when Christine had an affair with the band’s lighting director, Curry Grant. Grant was fired after Christine confirmed this to the rest of the group, but that didn’t improve matters between her and John. In 1976, the couple divorced.

As all this was going down, Mick Fleetwood’s marriage—on shaky ground since his wife Jenny’s affair with Bob Weston a few years earlier—was also disintegrating, with Jenny hooking up with Mick’s friend (and Chicken Shack bass player) Andy Sylvester. Unlike the other four, he didn’t face the challenge of playing music at an arm’s length from his ex or soon-to-be ex day after day. Unlike the other four, however, he had to keep a grip on both managerial responsibilities (albeit with plenty of help from lawyer Mickey Shapiro) and his domestic situation. And not being onstage or in the studio with Jenny might have been more of a minus than a plus, as she found it increasingly hard to deal with his prolonged absences from home as their family grew up. Between bouts of separation and reunions, the Fleetwoods divorced in late 1975—though not for the last time.

These weren’t the best of circumstances to begin thinking about writing and recording the material for their next album. But with Fleetwood Mac becoming a runaway hit, the heat was on to capitalize on the surprise smash by getting a follow-up together, and sooner rather than later. In a more ideal scenario, this might have been a good time for the band to take a break and take stock of their fluctuating relationships. But at a time when the record industry expected an album from its hit acts every year or two, that wasn’t going to be possible.

A ticket for Fleetwood Mac’s September 27, 1975, show at Michigan Palace in Detroit. Moderately successful Los Angeles band Ambrosia shared the bill at this concert.

A ticket for Fleetwood Mac’s show at the Houston Music Hall on December 3, 1975.

With some remixing and additional guitar work from Lindsey Buckingham, the single version of “Say You Love Me” was a #1 hit in 1976.

Stevie Nicks at Fleetwood Mac’s concert at the Berkeley Community Theatre on February 28, 1977. This was just the second show of the tour they launched behind Rumours, which had been released at the beginning of February. Getty Images

Fleetwood Mac on the cover of a 1976 issue of Disco 45. The British monthly was not a disco music magazine, but a publication specializing in printing the lyrics of pop songs.

So an emotionally battered group began recording sessions for the album that would become Rumours in Marin County in February 1976. Work would commence at the Record Plant studio in Sausalito, just over the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco. As to why they didn’t return to Sound City, a dispute over royalties that Keith Olsen has recalled might have had something to do with it. It’s also likely, however, that a change of scenery was thought advisable to ameliorate intra-band tensions, which were so serious that some members were barely speaking to each other. Mick, John, and Lindsey would stay in houses the studio owned, with Stevie and Christine using apartments in a nearby condo.

The studio wasn’t chosen solely for the San Francisco Bay views, however. The Record Plant was already operating successful studios in New York (where albums by big names such as Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, and John Lennon were recorded) and Los Angeles when it opened a Sausalito branch in 1972. The Sausalito facility had already hosted sessions by Sly Stone, the Wailers, and Gregg Allman by the time Fleetwood Mac began using it, and Stevie Wonder did part of his 1976 smash Songs in the Key of Life there. As they had on their previous album, Fleetwood Mac would co-produce the record with studio professionals, engineers Richard Dashut and Ken Caillat getting promoted to co-producers in the course of the album’s sessions.

In contrast to the relatively briskly and efficiently recorded Fleetwood Mac, however, Rumours would be a protracted production, sometimes agonizingly so. Two months and more than three thousand hours of recording between February and April yielded little in the way of usable material. As John Grissim revealed in Rolling Stone that April, “Pianos (four in succession) refused to stay in tune, a 16-track recorder developed a habit of chewing up tape, and two members had bouts with the flu. As a result of the delays (which, in the case of the illnesses, cost over $1,000 a day in studio time), the band has managed to lay down only three basic tracks, putting the project well behind schedule.”

Lindsey Buckingham flashes a double-neck guitar at the Berkeley Community Theatre, February 28, 1977. Getty Images

The increased sophistication of studio technology, and the increased budget and time granted by labels to new superstars like Fleetwood Mac in the mid-1970s, could be a curse as well as a blessing. Much time was wasted renting what Fleetwood remembered (in Play On) as “every piano in the Bay Area,” only for an engineer dubbed “the Looner Tuner” to do more untuning than fine tuning. All of the piano tracks at the Record Plant had to be junked. One of the songs featuring Christine on piano, “Songbird” (on which her only accompanist was Buckingham, on acoustic guitar), was cut not in Sausalito, but in Zellerbach Auditorium at the nearby University of California at Berkeley.

A Stevie Nicks promo photo, late 1970s. Getty Images

Deficient equipment wasn’t the only obstacle hindering progress at the Record Plant. Some of the tunes still didn’t have words, a big problem when added lyrics changed the songs so much that early backing tracks had to be scrapped. Stevie and Christine would sometimes hide in each other’s rooms as their now ex-partners searched for them in their condo.

Too, the amenities at the Record Plant did not exactly discourage drug use. Tanks of nitrous oxide were available for recreation, and visitors would often use a sunken part of the premises (originally built for Sly Stone), nicknamed the Pit, to do cocaine. A batch of pot cookies packed such a punch that little work was done at one evening session, with nothing to show for around $1,000 of studio costs at night’s end. Drugs weren’t the only substances consumed to various degrees, with John McVie (as Caillat recalled in his memoir Making Rumours) hitting the bottle pretty hard at times.

More productively, Nicks used the privacy of the Pit to do some songwriting, composing Fleetwood Mac’s biggest hit there in a mere five minutes during the sessions. When she laid down vocals for that composition, little tinkering would be needed. “The first time she sang it [‘Dreams’], she did such a great job,” remarked Ken Caillat in Stevie Nicks Through the Looking Glass. “Typically we call that a work vocal, just a guide track that we plan on replacing later. But we tried to replace that lead vocal throughout the rest of the year, and there was some parts of the verses we could never beat. She could never improve the vocal part, so there was some sort of spontaneity that came with her first performance of that.”

Still, for the most part Fleetwood Mac was dissatisfied with the Record Plant results. The band briefly resumed the sessions at Miami’s Criteria Studios, where hits by the likes of Eric Clapton and the Allman Brothers had been cut. But ultimately, the core of Rumours would be recorded and mixed in several Los Angeles studios after all, including their old haunt Sound City. Most of this work involved numerous overdubs of instruments and vocals, Fleetwood claiming in Play On that “more or less all that we kept from the Sausalito sessions in the end were my drum tracks.” By the time fall arrived, the tapes had been played so often they were starting to deteriorate, and some seat-of-the-pants transfers of overdubs onto a backup master were necessary to save the album.

In the midst of this semi-madness, Fleetwood Mac fit in some spring and summer concert dates as “The White Album” continued its charge toward #1. They shared a bill with Peter Frampton at the annual Bill Graham Day on the Green spectacle at the Oakland Coliseum, and did a show with the Eagles on the July 4 bicentennial in Tampa. Between those two extravaganzas, parts of their May 2 show in Santa Barbara were filmed for a documentary on the band (now available in half-hour form as The Rosebud Film on a deluxe edition of Rumours). About ten days after that, they were filmed doing a few songs at a Hollywood rehearsal stage for the same documentary, including “Rhiannon” and the yet-to-be-issued “Go Your Own Way” and “You Make Loving Fun.”

That didn’t mean the band was any less perfectionist, as an impatient Warner Brothers waited for the final product, of which they (at the group’s insistence) had heard little or nothing. (Although Fleetwood remembers refusing “to play them so much as a note” in Play On, in Making Rumours Caillat does recall previewing “Go Your Own Way” and “Dreams” to applauding Warners executives after sessions had been underway for a few months, with Mick present.) Ten hours were spent getting a kick drum sound. One of the record’s eventual highlights, “The Chain”—actually a combination of parts of several different songs—was almost abandoned after countless attempts. Literally dozens of demos, instrumental tracks, rough versions, early takes, jams, and acoustic tryouts of songs from Rumours have been added to expanded CD editions of the record as bonus tracks. Often skeletal and quite different from the familiar final versions, these testify to both the group’s diligence and their difficulty in constructing exactly what they wanted.

In spite of two romantic breakups within the band around the time Rumours was recorded, Fleetwood Mac not only survived, but thrived. Getty Images

Unsurprisingly, there was also a lot of difficulty in maintaining civility and communication in light of their simultaneously terminating relationships. “It was very clumsy sometimes,” John McVie admitted in Fleetwood’s first autobiography. “I’d be sitting there in the studio while they were mixing ‘Don’t Stop,’ and I’d listen to the words which were mostly about me, and I’d get a lump in my throat. I’d turn around and the writer’s sitting right there.”

Beyond the realm of the romantic, Buckingham was upping the tension by increasingly asserting himself in the studio. According to Caillat’s memoir, at times he even played other members’ instruments if what his bandmates came up with wasn’t to his satisfaction. Caillat’s account also details Buckingham literally throttling him after the producer (at Buckingham’s instructions) had recorded over one of his guitar solos. (To his credit, Buckingham later admitted that Fleetwood came up with a better drum part for “Go Your Own Way” than the one he had suggested.) In a less fractious dispute, Fleetwood gave Nicks an ultimatum after informing her that her composition “Silver Springs” wasn’t going to make the album, telling her that unless she sang “I Don’t Want to Know” instead, she’d only have two songs on Rumours, not three.

In the end, their professionalism, and the remarkable persistence that had brought them to the brink of superstardom, won out over lingering infighting and jealousies. “The machinery of it, the roll of it, had already gotten so great that there was never any consideration of do we want to stay together, or do we want to approach this in another way,” explained Buckingham in the Classic Albums series documentary on the LP. “We just had to play the hand out. And the only way to do that was to take all of these feelings—say my feelings for Stevie, and vice versa—and to sort of cram them into one corner of the room, and then to get on with whatever was going on with your process in the rest of the room.”

In the end, seven studios were used, the tab running to a bit over a million dollars. Boiled down to the then-standard running time of forty minutes, a few songs that had been worked on didn’t make the final cut, such as Nicks’ “Planets of the Universe” and Buckingham’s tellingly titled “Doesn’t Anything Last.” One such number that did make it to a state of completion, Nicks’ “Silver Springs,” was another composition inspired by her breakup with Buckingham. To her disappointment, it was only used as a B-side to “Go Your Own Way,” though Richard Dashut would hail it as “the best song that never made it to a record album” in Classic Albums. Lasting eight minutes, it was simply too long to fit on the record. Even when it was cut down to four and a half, it couldn’t fit on either LP side without lowering the audio quality of the vinyl, which could only accommodate twenty-two minutes per side before fidelity was diminished.

Autumn concert dates were canceled to allow Fleetwood Mac time to finish the album, whose hoped-for release date had now been pushed back. The United States might have now been their base and chief market, but they hadn’t forgotten the continent on which they’d first made a mark, going to London for ten days in October to promote “The White Album” and the new version of the band to the European media. The jaunt also occasioned a couple of reunions that were more bitter than sweet.

A group portrait in 1977, the year Fleetwood Mac vaulted from stardom to superstardom. Getty Images

Meeting up with Peter Green at their hotel, the band—particularly their British contingent—was distraught to find an almost unrecognizably disheveled, overweight, and mentally unstable figure with whom communication was pretty much impossible. Such was Green’s deterioration that Christine McVie summed up his condition to early Fleetwood Mac biographer Sam Graham as follows: “You have to talk about Peter in the past tense, because Peter [as a] musician doesn’t exist anymore. Almost like Jimi Hendrix. Jimi Hendrix is dead. Peter isn’t dead. He’s worse than dead. He’s just a vegetable, you know. And it’s very sad… he was a great musician.”

Shortly after their London meeting, Green did a spell in a mental institution, as fallout from a murky incident in which he was alleged to have threatened early Mac manager Clifford Davis with a shotgun if Davis didn’t stop sending him royalty payments. Another veteran of their late-1960s lineup wasn’t doing much better. Danny Kirwan also saw the band on their London visit, and though he’d been out of Fleetwood Mac less than five years, he’d already had bouts with homelessness and alcoholism. Those would continue in subsequent years as Kirwan disappeared from the music business, issuing his final solo album in 1979. Mick Fleetwood has not even seen Kirwan since then, though he’d do a great deal over the next few decades to help Peter Green out, both musically and personally.

As another sour reminder of the land they’d left behind, Fleetwood Mac somehow failed to repeat its success in the UK. Failing to enter the charts until late 1976, it peaked at a mere #23; issued as singles, “Say You Love Me” and “Rhiannon” barely made the Top 50. Perhaps at this point, Fleetwood Mac was considered as much an American band as a British one, if not more so, now that they were firmly ensconced in Los Angeles.

Rumours had sold eight million copies by the time this ad ran, and eventually sold tens of millions.

On the cover of the June 6, 1977, issue of People. When it hit the stands, Rumours had been at #1 for two months.

If the three British members now felt like Americans of sort, they were in for an unwelcome jolt when they had problems going through immigration on their return to the United States. Somehow they hadn’t yet taken care of the formalities necessary for them to live and work in their adopted country, and had to quickly get the green cards that allowed them permanent US residency. In his two autobiographies, Fleetwood gives different accounts of how these were granted, intimating in the first that a meeting between the band and Indiana senator Birch Bayh helped pull some strings. In the later book, he remembers playing a fundraiser for Bayh (who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1976), but is uncertain whether it made a difference. (They’d also play a fundraiser for Bayh in 1980, when the senator was running for reelection, though he lost to future vice-president Dan Quayle.)

Stevie Nicks at a New York concert, 1977. Problems with her voice caused the cancellation of some Fleetwood Mac concerts that year. Getty Images

However, in order to secure US residency for himself, his daughters, and his ex-wife, Mick had to remarry Jenny Boyd. It was an apt conclusion to the strange musical chairs between partners as Fleetwood Mac ended one of the most successful, and stormiest, years of their career. If the storm would abate somewhat in 1977, the success would pick up even more momentum.

It wasn’t until January 4, 1977, that mixing was finally completed on Rumours, as the record first titled Yesterday’s Gone (after a lyric in “Don’t Stop”) was now known. It was John McVie’s idea to call it Rumours as a response to all of the rumors (as the word is spelled in the US) swirling around the group as their breakups became public knowledge and the follow-up to Fleetwood Mac failed to appear. Some of said rumors speculated the band would break up before another album could be released, or at least that the personnel would change as one, two, or three members left for a solo career and/or different groups.

While none of this took place, the first taste from Rumours made it clear the band’s messy personal relations would make their way not just into the mass media, but also into their actual songs. Released at the end of 1976 as a single a couple months in advance of the LP, Buckingham’s “Go Your Own Way” was something of a kiss-off to Nicks, who was especially ticked off by the line accusing her that packing up and shacking up was all she wanted to do. Not true, according to Nicks. But that didn’t keep it from becoming their first Buckingham-penned hit, as well as supplying invaluable pre-publicity for the Rumours album itself.

Stevie Nicks on stage in October 1977. In June, her composition “Dreams” had reached #1 on the singles charts. Getty Images

“This album reflects every trip and breakup,” Fleetwood divulged to Melody Maker in June 1976, as the record was still very much in the process of getting completed. “It isn’t a concept thing, but when we sat down listening to what we had, we realized every track was written about someone in the band. Introspective and interesting, kind of like a soap opera. The album will show sides of people in this group that were never exposed before.”

From the very first lines of Rumours, it was apparent that “Go Your Own Way” wouldn’t be the only track to discuss the band’s recent romantic fallouts. There’s nothing to say, sang Buckingham in “Second Hand News,” who then proceeded to say (or sing) a lot about someone having taken his place and needing to do his own thing. Credited to the band as a whole, “The Chain” might have spoken for everyone in its exhortation “damn your love, damn your lies.”

Yet that same song ended by urging “The Chain” to “keep us together.” And staying together as a band, if not as lovers, was proving more important to the quintet than splitting over their nonmusical issues. Other songs on Rumours took a more optimistic view of romance and keeping hope alive in the face of the most formidable foes. Several of those would not just follow “Go Your Own Way” into the Top 10, but would become even bigger hits, in turn propelling Rumours not just to #1, but to the Top 10 all-time best-selling recordings.

First out of the box was Nicks’ “Dreams,” a much gentler and less direct commentary on the end of a relationship than “Go Your Own Way.” Quickly replacing “Rhiannon” as her most popular composition, it remains Fleetwood Mac’s only single to reach #1 in the United States. On its heels was Christine McVie’s anthemic, more upbeat “Don’t Stop,” written in part as a message to ex-husband John to keep on trucking after their separation (and sung in part by Buckingham, who handles the first verse). A big success in its own time (soaring to #3 in summer 1977), it’s arguably even more popular than “Dreams” these days, as it was used as the theme song for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign (and continues to be played when he appears at Democratic National Conventions). As a reminder that love didn’t stop with divorce, Christine’s funkier, wistful “You Make Loving Fun” became a Top 10 hit later in 1977—the fourth from Rumours.

Four big hits alone, however, can’t explain the phenomenal success of Rumours, which dwarfed even that of “The White Album.” Songs like “The Chain,” “Second Hand News,” and Nicks’ “Gold Dust Woman” got so much FM radio airplay they were something of unofficial hit singles under their own steam. As a whole, the album hung together more tightly and organically than any of their previous LPs, radiating a consistency that made listeners want to play it over and over.

Even the cover art helped, with its strikingly stark photo (by Herbie Worthington, who’d also photographed the Fleetwood Mac cover) of an elegant Fleetwood perching on a footstool as he towered over a floridly dressed Nicks. In keeping with her burgeoning image as rock’s cosmic princess, her flowing cape made her look as if she’d literally just flown in from an angels’ convention. Set against a white background, their rather intimately interwoven pose was an early indication, in hindsight, of the next passionate flare-up that made life in Fleetwood Mac so simultaneously thrilling and miserable.

Nor was the band above using their now-well-publicized bust-ups to their own advantage. Shot by top photographer Annie Leibovitz, the cover of the March 24 Rolling Stone showed them literally in bed with each other, and not with their longtime partners. Fleetwood was entwined with Nicks; Christine McVie with Buckingham; and John McVie, oblivious to the hanky-panky, lay on the side alone, reading a magazine.

To add to the titillation, in the article itself, Nicks made it clear that all her songs on Rumours, except perhaps “Gold Dust Woman,” “are definitely about the people in the band… Chris’ relationships, John’s relationship, Mick’s relationship, Lindsey’s and mine. They’re all there and they’re very honest and people will know exactly what I’m talking about… people will really enjoy listening to what happened since the last album.” Even “Gold Dust Woman” might qualify as a commentary of this sort, Nicks describing it twenty years later (in the Classic Albums documentary) as a “symbolic look at somebody going through a bad relationship and doing a lot of drugs.” Nor was every relationship the tunes documented romantic, Christine penning “Oh Daddy” about Fleetwood, at that time the only father in the band.

Fleetwood Mac were literally in bed with each other on the cover of the March 24, 1977, issue of Rolling Stone, the month after Rumours was released.

Happy together on stage, 1977. Fleetwood Mac toured extensively throughout the year in support of Rumours, playing shows in North America, the United Kingdom, Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and Japan. Getty Images

For all of these reasons, Rumours was an instant hit, reaching #1 a couple of months after its February 1977 release. Its ascent was hardly unexpected. It had the largest advance order from record stores—almost a million copies—of any album in Warner Brothers history. The Fleetwood Mac album had already sold four million copies, and with “Dreams” entering the charts the same month Rumours made #1, it could be expected to settle in the pole position for a few weeks.

Then something unprecedented occurred. The album was #1 for thirty-one weeks in 1977 (its streak only interrupted by one week in which Barry Manilow’s Live took over the top spot), a reign longer than any previous rock LP had enjoyed (including 1977’s other blockbuster, the Eagles’ Hotel California, whose nearly unbroken reign at #1 a few months earlier lasted a mere two months). Within a year of its release, Rumours had sold more than ten million copies, more than eight million of those in the United States alone. Estimates of its total sales vary, but the Recording Industry Association of America certified it as passing the twenty million mark in 2014, with other sources citing figures of more than forty million worldwide. It wasn’t until 1983 that the thirty-one-weeks streak would be broken—and it would take the biggest-selling album of all time, Michael Jackson’s Thriller, to do it.

“It is still super special and fresh,” mused Nicks about the record’s perennial popularity in the liner notes to the 2013 expanded edition. “Somehow it doesn’t sound old. It’s kind of creepy almost how it doesn’t get old. A lot of classic records we all love, if it comes on the radio, we’ll all say, ‘Wow, that really dates me,’ and the answer is usually, ‘Well yes, it does.’ But I don’t think there’s a date attached to Rumours. At least to my ears, Rumours still sounds like it could have been done in your living room three days ago. And maybe that’s why we still love it so much because somehow it still has an air of almost being new.”

Rumours also accumulated its share of awards, winning the 1978 Grammy Award for Album of the Year. It also notched the rare grand slam of getting named Album of the Year in each of the three major US music trade magazines (Billboard, Cash Box, and Record World), as well as by Rolling Stone’s readers’ poll. Many years later, Rolling Stone placed it at #26 in its list of the five hundred greatest albums of all time, hailing it as “the gold standard of late-Seventies FM radio… on Rumours, Fleetwood Mac turned private turmoil into gleaming, melodic public art.”

Stevie Nicks and Fleetwood Mac performing in 1978.

Fleetwood Mac bumper sticker, inspired by the band’s trademark penguin logo.

Why this one-of-a-kind shower of praise and sales for Rumours and not, say, Hotel California, or Linda Ronstadt’s Simple Dreams, which sat at #1 for the final five weeks of 1977?- Rolling Stone dedicated much of a January 1978 article to that very question. After batting around several theories, author Dave Marsh and Warner Brothers Senior Creative Services Director (and ex-Beatles publicist) Derek Taylor basically came to the same deduction as the millions of fans buying the LP. Rumours, they concluded, was simply “a very, very good two-sided pop record.” It didn’t so much fit in perfectly with late-1970s commercial FM radio as define late-1970s commercial FM radio. Ironically, it did so at the very time when the Sex Pistols’ “God Save the Queen” was shooting to #2 in the UK, lighting a punk and new wave explosion that would eventually threaten the dominance of the slickly produced California soft rock of acts such as the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, and Fleetwood Mac themselves.

The Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the Ramones were still fairly distant blips on the radar to the rock mainstream when Fleetwood Mac launched a worldwide tour in support of their new mega-smash. The days of playing support to or getting co-billed with mid-level AOR acts were long gone. Fleetwood Mac was now selling out arenas coast-to-coast under their own power.

Gone too were the days of tentatively mixing new material with old favorites. The set was now devoted almost exclusively to songs from “The White Album” and Rumours. Often these were given a harder rock edge onstage, as 1977 concert recordings on expanded editions of Rumours prove. “Rhiannon” in particular underwent a transformation, stretching to eight minutes as Nicks almost screamed herself hoarse in the extended closing section.

And while old favorites like “Station Man” and “Hypnotized” were still in the program in the ten US dates they played in February and March, by the time they returned from a series of European shows for the second North American leg of the tour in May, even those had been retired. Fans were coming to see the Buckingham-Nicks lineup, and to hear the songs from their two hit albums. Many of them didn’t even know the names of Danny Kirwan, Jeremy Spencer, or Peter Green.

Between those North American jaunts, Fleetwood Mac made a triumphant return to Europe and the UK, where Rumours was becoming a big hit as well (though it wouldn’t top the British charts until early 1978, and singles culled from the album were only modest sellers). Buckingham and Nicks also managed to find time to co-produce Walter Egan’s second album Fundamental Roll, which generated the Top 10 hit “Magnet and Steel.” There would be no rekindling of their personal relationship, however, with Stevie getting involved with the Eagles’ Don Henley and singer-songwriter John David Souther for short spells.

As serious money poured in, the band’s lifestyle upgraded accordingly, a private jet and limousines replacing the station wagons in which they’d driven from date to date. Nicks even insisted on pink rooms with a white piano, which often had to be lifted through the window by hired crane. Drug use accelerated as well, and while Fleetwood has denied his excesses were quite as monumental as some tabloids would have it, he makes no secret of the band’s heavy indulgence in cocaine, in particular.

Along with the high times came new stresses, including a threat to one of their most vital musical assets. Stevie’s voice couldn’t quite hold up under their heavy touring schedule, causing cancellation of some dates. Her voice, reported Rolling Stone in its review of their June 29 show at New York’s Madison Square Garden, “was the audience’s prime discussion topic before and after the concert… she couldn’t summon the chops to get away with anything,” finding it “impossible to hit ‘Rhiannon’s higher notes.” She sometimes resorted to shots to keep the swelling in her vocal cords down, the band also adding a voice coach to their touring unit.

Nicks wouldn’t get the chance for the extended rest her voice might have needed. Just a month after wrapping up the second leg of their North American tour in Santa Barbara on October 2, Fleetwood Mac was off to New Zealand, Australia, and Japan for a month, doing their final show of the year on the way back in Maui. During the break in the schedule, Nicks and Fleetwood began an off-on two-year affair, though Fleetwood was still married (or remarried) to his first wife at its onset. On top of all of Fleetwood’s other obligations and complications, his father had been diagnosed with cancer in August, dying a year later.

By the late 1970s, Fleetwood Mac was traveling in high style, and the days of hauling themselves between gigs in station wagons were becoming a thing of the past. Getty Images

In the midst of the most successful and stressful year of his life, Fleetwood found time to extend a helping hand to a couple of old friends, with mixed results. One was Peter Green, who briefly moved to Los Angeles, where he was married in the home of Mick and Jenny Fleetwood on January 4, 1978. Fleetwood also got Green a record deal with Warner Brothers, reported by more than one source to be in the vicinity of a million dollars.

But there was only so much he could do for a figure as unstable as Green had become. Green decided not to sign, declaring the offer to be (as Fleetwood remembered in Martin Celmins’ Peter Green: The Biography) “the work of the devil.” He’d also given away a $5,000 Les Paul guitar Fleetwood had bought for him to a stranger in a hotel elevator (though it was soon recovered). Returning to England, Green did resume his recording career with a few solo albums in the late 1970s and early 1980s, though these gained little in the way of either sales or critical notice.

Rumours was selected as the #1 album of the year in Rolling Stone’s 1977 readers’ poll.

On the cover of the second issue of Grooves magazine, 1978.

Just two-and-a-half years after gracing the cover of People when Rumours was #1, Fleetwood Mac did it again on November 26, 1979. Ironically, they were placed under the headline of a different article in the issue titled “Saving Marriages.”

Nor had Fleetwood forgotten Bob Welch, whose two mid-1970s albums as leader of the hard rock trio Paris had not fared well. He played drums on the big hit from Welch’s 1977 debut solo album French Kiss, “Sentimental Lady,” with Christine McVie pitching in on keyboards and backup vocals, and Lindsey Buckingham adding some guitar and vocals. Arguably overextending himself, Fleetwood (who was still handling his own band’s affairs) also took on managerial duties for Welch.

In contrast to the failed relaunch of Peter Green’s career, Bob Welch’s comeback of sorts could have hardly gone any better, at least at first. Suggested by Fleetwood and arranged by Buckingham, Bob’s soft rock remake of “Sentimental Lady,” originally issued by Fleetwood Mac on 1972’s Bare Trees, made #8. French Kiss, which was likewise more pop-oriented than Welch’s albums with Paris, rose to #12, with another of its tracks, “Ebony Eyes,” becoming a substantial hit in early 1978. Welch would also tour with Fleetwood Mac in 1978, though the good feelings wouldn’t last forever.

As remarkable a year as 1977 had been for the group, they weren’t going to be able to take a year or so off to rest on their laurels, or rest Stevie Nick’s voice, or resolve their complicated personal and business affairs. Nor, it seems, did they even want to. The Buckingham-Nicks version of Fleetwood Mac had only been together for three years and two albums, and only really started to explore what they wanted to do musically, as quick and huge as the payoff had been. Their record label and fans were as eager for a follow-up to Rumours as they had been for a follow-up to Fleetwood Mac, the stakes now upped exponentially by Rumours’ record-breaking sales.

Bob Welch’s French Kiss album was a big hit for the former Fleetwood Mac guitarist. Reaching #12 in the charts, it featured the hit single “Sentimental Lady,” a remake of a song he’d also recorded years earlier as part of Fleetwood Mac.

The logical thing to do would have been to record another album filled with the kind of pop-rock songs Lindsey, Stevie, and Christine were so skilled at delivering, and John and Mick so adept at helping to polish and perfect. No doubt that’s what Warner Brothers wanted, and that’s likely what Fleetwood Mac’s now-massive fan base expected. Even a pale reflection of the previous two records would have been guaranteed sales of several million, had the material been in the same style.

If there was one predictable aspect to Fleetwood Mac’s career, however, it was its very unpredictability. Even in their most popular and apparently stable lineup, that wasn’t about to change. Their next album would not be at all like Rumours, and indeed not like anything else anyone was doing in the late 1970s.

Lindsey Buckingham at the Oakland Coliseum, May 7, 1977. Fleetwood Mac played this concert as part of promoter Bill Graham’s Day on the Green series, sharing the bill with the Doobie Brothers and Gary Wright. Getty Images

One thing would not change, however. Like Rumours, the sessions for their next album, which began in May 1978, would be costly and drawn-out. But the only record Tusk would set was for the most expensive rock album ever made prior to 1980. That was just one of the controversies that plagued a project that remains Fleetwood Mac’s most ambitious.

From the get-go, the band was determined that the record wouldn’t be a repeat of Rumours. They, or at least a couple of them, had been down this road a decade earlier, when they branched out into non-blues-confined rock with Peter Green and Danny Kirwan on 1969’s Then Play On, though they could have been assured of steady sales if they’d stuck to the blues that had put them on the map. It had worked pretty well then, both in the quality of the music produced and the quantity of copies it sold. Could it work again?

A 1977 group portrait. The success of Rumours continued to build throughout the year with a series of hit singles, including “Go Your Own Way,” “Dreams,” “Don’t Stop,” and “You Make Loving Fun.” Getty Images

Lindsey Buckingham in particular was adamant that new ground had to be broken. Fleetwood Mac wasn’t about to suddenly go punk and new wave as those styles became all the critical rage, especially in the UK. But as someone who kept up with bands like the Clash, he wanted his own band to sound contemporary, and not like one of those dinosaurs that punks were accusing complacent rock superstars of becoming. That didn’t mean that he wanted Fleetwood Mac to sound like the Clash or Talking Heads, but he did want the group to become more daring and take more risks.

“I think if we hadn’t done that album, then Lindsey might’ve left,” pondered Christine McVie in Creem. “We ‘allowed’ him to experiment within the confines of Fleetwood Mac instead of saying, ‘We don’t want you doing stuff at your studio and putting it on the Fleetwood Mac album’—he might’ve said, ‘I’m gonna leave, then.’ We didn’t want him to leave, for obvious reasons.”

“The axiom ‘if it works run it into the ground’ was prevalent then,” Buckingham commented in Rob Trucks’ book Tusk. “We were probably poised to do Rumours II. I don’t know how you do that, but somehow my light bulb that went off was, ‘Let’s just not do that. Let’s very pointedly not do that.’ And we had a meeting and I talked about it. The band was a little wary at first. They got more and more drawn into it as it went along.”

As Nicks remembered it in Jim Irvin’s liner notes to the 2015 deluxe edition of Tusk, however, the band wasn’t insistent on repeating Rumours. “Lindsey was really making a stand. ‘I’m not doing Rumours over!’ And the rest of us were like, ‘What do you mean? Why would any of us want to do Rumours over? We just want to make a great new record.’ If you want to go down some different pathways, research some different genres of music and change it up, everybody was fine with that, but Lindsey was just so adamant about doing something that was the opposite of the previous records. He announced it so visually, so demandingly that I think he scared us. We were like, ‘What the fuck?!’”

Lindsey Buckingham at the Grammy Awards on February 23, 1978. Getty Images

Continued Stevie, “Mick was onboard for shaking things up, because he wanted to make an African record. He was saying, ‘Let’s do a native record with chants and amazing percussion.’ I love that too, so great, and Christine was fine with that and John would have liked to have been in an all-black blues band, so he was onboard. We were definitely all on the rhythm train. We set off on this journey to the top of the mount, and this record started to unravel itself in The Village [recording studio] and become something entirely different.”

One of the first steps taken, however, was something way beyond the budget of even the most successful new wave acts. Mick Fleetwood thought they should build their own studio, especially after Rumours had found them using different studios in three different cities before they got exactly what they wanted. A state-of-the-art facility called Studio D was constructed at LA’s The Village Recorder for this purpose, the final bill running about $1.4 million. While no expense was spared in setting up the best equipment, considerable cash was spent on nonessentials like a lounge with English beer on tap, and huge ivory tusks on each side of the console. And, Fleetwood’s intentions to the contrary, after all that money had been doled out, they didn’t actually own the studio—the kind of planning that would land Fleetwood in serious financial trouble in the near future.

Nor would the band go into the studio, work single-mindedly on the sessions for a few months, and promptly come out with a finished product. This being Fleetwood Mac, there were plenty of distractions and crises to impede the flow chart. Mick and John played on “Werewolves of London,” the breakthrough hit for Los Angeles singer-songwriter Warren Zevon. The band played nearly a dozen shows in big American venues in July and August, including such huge ones as the Cotton Bowl in Dallas and JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, both of which had around one hundred thousand seats. Buckingham recorded many of his parts for some works-in-progress at home, at times banging on shoeboxes for the rhythm and cutting vocals in his bathroom. In the process, he upset some other members of the group, particularly the McVies, who felt he should be doing all his work as part of the team in a proper studio.

“When we started the album, we had a meeting at Mick’s house,” remembered Buckingham in Trouser Press. “I said I had to get some sort of machine into my house as an alternative to the studio. The trappings and technology of the studio are so great—the blocks between the inception of an idea and the final thing you get on tape are so many—that it just becomes very frustrating. That was why my songs turned out the way they did: the belief in a different approach. For me it wasn’t really a question of changing tastes, but of following through on something I’d believed in for a long time and hadn’t had a means of manifesting.”

Stevie Nicks at the Alpine Valley Music Theatre in East Troy, Wisconsin, on July 19, 1978. Getty Images

Their domestic situations continued to be as unsettled as ever. Fleetwood’s father died in summer 1978, and his marriage crumbled soon afterward. Mick’s confession of his fling with Stevie sealed the end of his relationship with his wife, as did his increased drinking. Christine embarked on a torrid affair with Dennis Wilson after meeting the notoriously volatile Beach Boys drummer at The Village Recorder, where he was working on a solo album. Earlier in 1978, John McVie had married Julie Rubens, with Mick acting as best man.

The extracurricular activities didn’t get in the way of the band spending many hours in the studio, and spending more money on the recording than anyone had on any album. It took just under a year to complete, also taking up 175 reels of two-inch tape and almost 400 mix reels. As if to underscore his determination to give the record a different sound, on the very first day of recording, Buckingham asked Ken Caillat to twist every knob 180 degrees to “see what happens.”

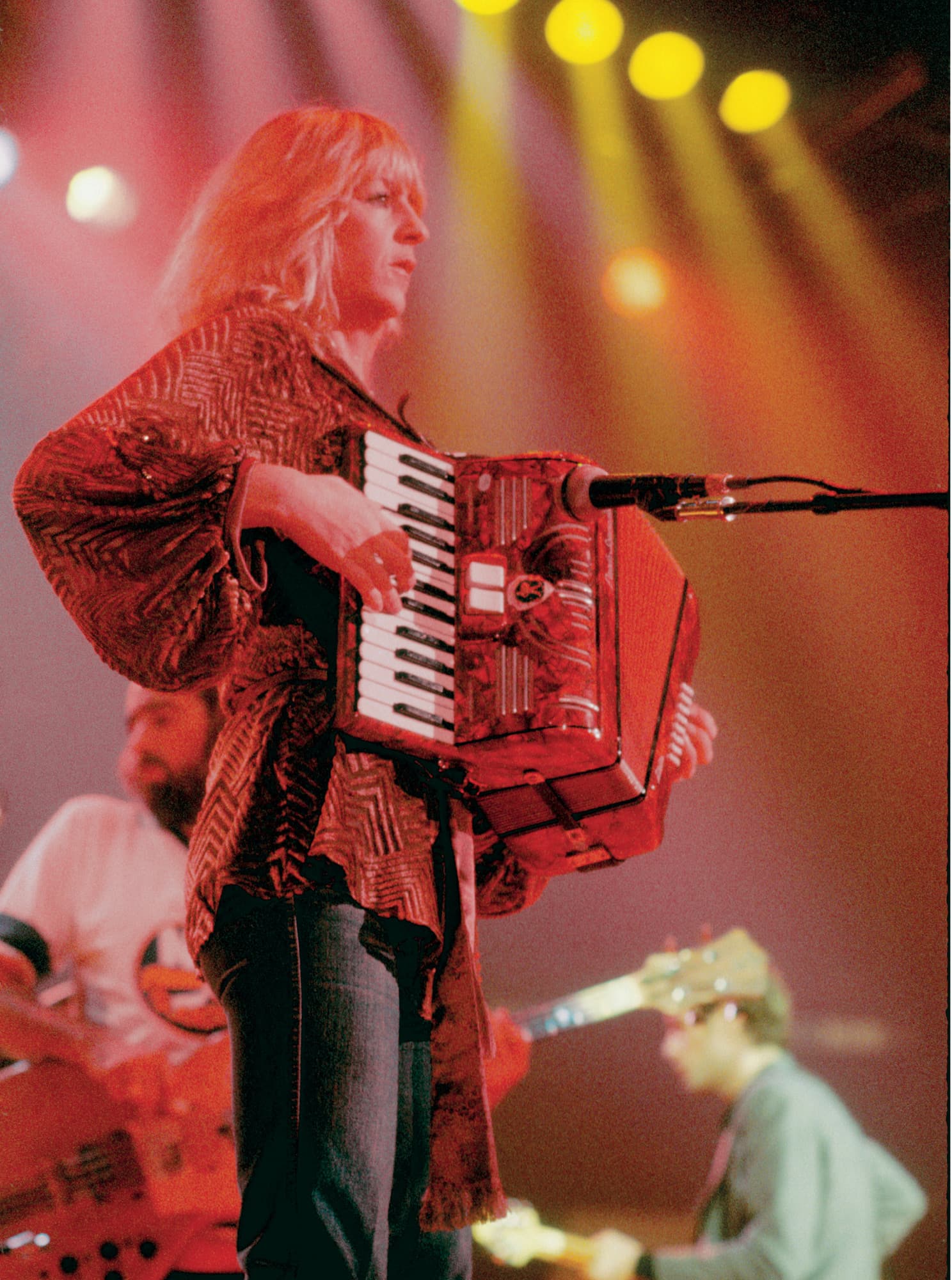

Christine McVie on accordion in concert with Fleetwood Mac, late 1970s. Getty Images

The stretched-out schedule wasn’t solely due to their perfectionism, or a willingness to spend money that many viewed as indulgent, even decadent. With three writers and a generous two-year gap between albums, they were coming up with more songs than ever. Enough, it soon became evident, for a double album, co-produced by the band with Richard Dashut and Ken Caillat. The three distinct but complementary kinds of compositions, as well as a growing appetite for experimentation, meant that Fleetwood Mac could now deliver their rough equivalent of the Beatles’ The White Album, another double LP that had made the most of these attributes. In another echo of the late 1960s, Peter Green made an uncredited guest appearance on the final section of Christine McVie’s “Brown Eyes,” though his guitar is pretty low in the mix.

For all its reputation as something of a mad scientist laboratory exercise that grew out of control, Tusk isn’t all that weird. It’s not even as eccentric or eclectic as The White Album. The tracks written and sung by Christine McVie or Stevie Nicks were pretty much in line with the romantic pop they’d offered on the previous two albums, though perhaps not as bubbly or catchy. Buckingham’s material, in contrast, was usually brittler in both construction and production, with a jagged, almost nervous feel that let his new wave inclinations into the mix, though not so much that the tracks could be mistaken for new wave.

To some degree, a bit of stripped-down new wave seeps into the production of some of the other songs too, especially in the rhythms and percussion. Fleetwood even asked Buckingham to make the songs he’d written more identifiably Fleetwood Mac in nature during the mixing process. But even some of Buckingham’s less pointed departures from Rumours weren’t quite like what he’d done on the previous two albums, with the dreamy “That’s All for Everyone” coming off as something of a tripped-out psychedelic ballad with Caribbean overtones.

The title track, however, was as off-the-wall a cut as some listeners were bracing themselves for as reports of the elaborate Tusk sessions made it into the media. In fact, it was as off-the-wall as anything Fleetwood Mac had done, going back to the classical ending of “Oh Well” and Jeremy Spencer’s rock ’n’ roll parodies. Growing out of a riff the band played at sound checks, “Tusk” was not so much a song as a chant, its tribal rhythms overlaid with the same riff played by the University of Southern California Trojan Marching Band. The 112-strong USC outfit recorded their contributions in an empty Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, with the proceedings filmed for posterity, although John McVie was represented only by a life-sized photo, as he was on holiday in Hawaii.

By the time recording wrapped up in early summer 1979, they had not only enough material for a double album, but enough demos and outtakes to fill up a couple CDs on the five-disc 2015 deluxe edition of Tusk. They wanted all twenty of the finished tracks to be released, and understandably thought they had enough pull with Warner Brothers to justify such a package. In the CD era, all seventy-two minutes could fit on a single disc. Back in 1979, a double LP would be necessary.

The label initially balked at doing so, hoping the band would condense it into a single vinyl disc—something, incidentally, that producer George Martin had unsuccessfully tried to get the Beatles to do for The White Album. Whereas Martin’s rationale had been to boil the sessions down to the very best songs, however, Reprise/Warner Brothers likely had more mercenary motives. As executive Mo Ostin told Fleetwood, the record industry was in a slump as the 1970s ended, generating fears that a double album wouldn’t sell nearly as many units as a standard single LP. With the absence of songs that were nearly as obvious candidates for hit singles as Fleetwood Mac and Rumours had boasted (with the possible exception of “Sara”), the label could already have been mentally picturing a zero vanishing from the end of their projected sales figures.

Lindsey Buckingham at the Alpine Valley Music Theatre in East Troy, Wisconsin, on July 19, 1978. Getty Images