ON DECEMBER 15, MR. CAMPBELL was stabbed seven times in the chest. He died on the way to hospital. He was sixty-five.

The first Sam knew of it was when he saw the trail of blood. It ran past his shop, finishing on the corner. It was early, he was still sleepy, and the blood was hard to believe. He stood in the doorway, drinking coffee, wondering who it had come from. When it began to rain, softly at first, then heavier, he thought it would quickly wash the blood away, but it took a long time.

Over the next few days, many people said how dreadful, shocking, awful, and terrible it was. Though they shook their heads and looked grave, none said, He was a fine man or He was a good man or that they would miss him. There was speculation about the will. Some said Mr. Campbell had relatives in France; others that his money would go towards a sanctuary for old horses. What everyone agreed on was that Stephanie would get nothing. Her divorce from Mr. Campbell had been protracted and bitter; it had taken the court three months to rule that there was clear evidence of mental cruelty on his part, more than enough to offset her single act of infidelity with Charming Robert. The settlement was generously in her favour, so much so that Mr. Campbell took out a full-page advert in the local paper that consisted of a jeremiad about the biases of the judicial system, in particular “its susceptibility to the pathetic lies of weak, attention-seeking people.”

The police had no suspects. They did not know that the last person who had seen him that night was Trudy (who told this only to Sam). She said Mr. Campbell seemed no different. As usual, he lay on the bed and closed his eyes tightly and made her slowly undress him. This was by far the most difficult part, because he made no effort to help her, did not even raise his arms. It took twice as long as the sex itself, which was over quickly. “Thank you, Stephanie,” he said, then put on his clothes and left. Within ten minutes he was dead.

When the will was read, only Trudy and Sam were not surprised. Barring a few small bequests, he left everything—the house, the antique shop, the contents of his bank accounts—to the ex-wife he had bullied and belittled for seventeen years. Almost equally surprising was how modest his estate turned out to be. Though he had aped the manners of the upper classes and often referred to his antique shop as “a hobby,” he was no wealthier than most of the storekeepers of Comely Bank. He was certainly not as successful as Mr. Asham.

In addition to the main bequest, the will stipulated that all his clothes should go to Caitlin’s charity shop, and all his books to Sam’s. Neither could remember him ever entering their shops. He also specified that his gas-powered barbecue should be given to Mr. Asham. The general tenor of the will was thus one of making amends. The question was why an otherwise healthy man should have put his affairs in so final an order. Of some relevance might have been the fact that he was not killed for his money. His moderately expensive watch stayed on his wrist. His wallet was untouched.

The only possible motive was found by Sam in Mr. Campbell’s desk. The executor of the will had asked Sam to help box up the deceased’s extensive library. After three hours, and thirty-two boxes, he had finished except for a set of Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The books were heavy, covered in dust, mostly on high shelves that could be reached only by ascending a metal stepladder broken in a number of places; not only was the ladder unstable, it also had sharp pieces of protruding metal. During the entire exhausting, dirty process, the executor made no attempt to help. He hovered on the edges of the room, speaking on his phone in a voice so horribly nasal his mouth seemed uninvolved. Only when Sam had run out of boxes did the executor interrupt himself to say he had more in his car.

As soon as he heard the front door close, Sam went to the mahogany desk. He didn’t know what he expected to find. He just had to look.

The top drawer was empty.

So was the middle.

The bottom one was locked.

He grabbed a letter opener from the desk then pushed it into the lock. He had no idea what he was doing; he was in a frenzy.

The lock must have been old, fragile, or poorly set in the wood, because Sam was able to push it in. Inside the drawer was a large tin box. Inside it was another box. Inside it was a third that contained a black ski mask and three photographs. One was of Stephanie sleeping in a patch of sunlight. On the back it read: St. Albans. 1998. In the second Trudy had her arms tied behind her back. The third picture was of a boy who was crying. He was eight or nine and wearing makeup, far too much. Behind him was a full-length mirror in which the photographer was reflected. It was not Mr. Campbell or any man that Sam recognised.

Sam put the mask in his pocket and the photos inside a book. A moment later the executor returned empty-handed. “I’m afraid you’ll need to come back tomorrow,” he said.

It took most of the next morning to transport the boxes to the shop. Sam spent the rest of that day, and most of that night, going through the books. He turned the pages slowly and with great care, anxious not to miss any ephemera. Most of the books were bound in leather and had had many previous owners. Their names were written in ink over a century old. He learnt that first Nathaniel Murray, then Elizabeth Griffin had owned a booklet entitled Mastering Shyness Through Auto Suggestion. He found anti-Semitic remarks throughout the Old Testament of a family Bible belonging to the MacAllisters of Dundee. There were tram tickets and pressed flowers, banknotes from countries that had long since vanished. It was an embarrassment of riches, but Sam was disappointed. He had never seen so few traces of someone in their books.

In part, this was unsurprising. These were rare, valuable books that Mr. Campbell had probably never read. Even if he had, he would not have turned over the corners of their pages, or written notes in their margins.

By the time Sam got to the last box he had given up hope. At first glance, the books inside seemed no more promising than the rest. They were bound editions of an Edinburgh newspaper from the nineteenth century, not the sort of book to inspire a reaction from Mr. Campbell. On all but one the year of publication was stamped on the spine in gold letters, but there was a single volume whose binding was darker and whose year had rubbed off. It was only to ascertain whether it was from 1870 or 1879—the other volumes covered the years in between—that he opened it. The binding felt odd, much rougher than leather—if anything, more like scales. If the book was smaller and lighter than the other volumes, this was because it was not one of them. Instead of columns of newsprint and illustrations, there were brown boards on which photos were mounted. They were mostly family pictures from the 1920s and ’30s. There were photos of weddings.

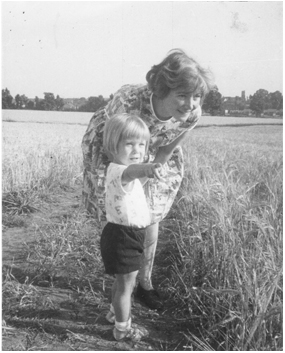

There were photos of holidays:

And of people dancing in their gardens.

There were almost sixty photographs in the album. They were from a time that no one could remember, not even Mrs. Maclean. Which is not to say these scenes seemed strange to Sam (as they must do to us). When he looked at these people and places he saw many things that had changed, but also some that had not. Maybe it was not the same world as his, but they were related.

It was three o’clock in the morning when Sam finished looking at the album. He felt a pleasing throb of sadness. These people were long gone, but they had been happy, felt love for each other. The children seemed content; the parents looked dependable. His only regret was that their family name was McRae, not Campbell.

That night he slept in the shop. In the morning he washed his face and hands in the sink, then began to price the books. When he came to the album, he hesitated. Perhaps it was too soon to sell it. He had been so tired; he might have missed something.

He was still hesitating when he opened the shop. His first volunteer was bulimic Dee, who sat at the till and gripped her elbows while he priced the rest of the books. Boring Lesley came in at eleven, shortly after which they sold one of Mr. Campbell’s volumes for £500. In some respects, not a lot of money. But enough to pay a social worker for an extra day’s work—so they might visit a child a week earlier, so they might see bruises before they healed.

That afternoon Sam put the album in the shop window and felt a tremendous relief. Sometimes he felt he was wasting his time on questions he did not need to answer. Perhaps he didn’t need to understand why apparently good people could make terrible parents, and vice versa, in order to take the risk that everyone took without thinking. It wasn’t as if he’d have to justify having children: It was the “normal” choice. It was not wanting to have any that required explanation. And if he did have sex, and it led to a baby, and if he and the mother raised this child, perhaps it didn’t matter that there was no way to guarantee that they wouldn’t fuck it up. If, for example, they were emotionally distant, and their child subsequently grew up with trust issues that made it hard for him/her to form meaningful relationships, they would be breaking no law. They would not be publicly condemned. Even if the child grew up to be a murderer or tyrant, they would still get away with it. It was not like hitting a child: That left marks others could see. If they were cruel, no one would ever know, except themselves and the child—and sometimes, if they were lucky, the child might not know either. But they would, and always.

Sam sold two more of Mr. Campbell’s books. Magda came in at four. She was an elegant lady with bright silver hair who had buried three husbands. She was carrying a small cage wrapped in a blanket that contained her rat. “She doesn’t like the cold, do you?” she said into the cage.

Sam went into the back office, shut the door, and put his head on the desk. Magda could look after the shop. He needed to sleep.

He closed his eyes and soon was dreaming of climbing a steep hill to watch an organised flood. Sinead was admiral of the fleet; Toby was dressed as a whale. There was a mock battle with pirates and cannons. Metal balls roared through the air, blasting through timbers and rigging. The air was full of smoke and shouting, the screams of people injured. As he felt the table under his head, and knew where he was, there was a shout about thieves.

“Stop shouting,” Magda shouted.

Sam stood and opened the door and saw Alasdair at the counter. He was holding his bicycle with one hand while jabbing a finger at Magda.

“It’s mine, and you took it.”

“Stop shouting,” she said more quietly. “You’re upsetting her. She doesn’t like it.”

This confused Alasdair long enough for Sam to interrupt.

“What’s wrong?” he said.

“He says we stole that photo album.”

“It’s mine,” said Alasdair. “Those photos are mine.” He stopped talking and put a hand on his chest, as if the words were causing him pain.

“We didn’t take them,” said Sam. “They were donated.”

“By a thief. They are—” He hesitated. “My family. Give it to me.”

“I’m sorry, but I can’t, not unless you can prove it’s yours.”

“They took it. They beat me, and they took it.”

“Who took it?”

Alasdair shook his head impatiently. “I don’t know. They had masks, they had black faces. I want it back,” he shouted, and then Magda hit him hard in the throat. Alasdair made a choking sound, then staggered from the shop.

“I warned him,” said Magda.

“Did you?” said Sam, but she wasn’t listening. He watched as she kissed Daphne. The rat’s tail twitched with pleasure. Could she feel that way about a child? Somehow he doubted it.

For the next hour he dozed and thought about Mr. Campbell’s black mask. If he was willing to beat up the homeless, what else might he and the others have done? Perhaps one of them was the man in the picture with the boy. Why did Mr. Campbell have this picture? It was definitely not a picture you wanted someone else to have. They could blackmail you. You would have to give them money, do exactly as they said. You would become desperate. You would do anything to make them stop.

But although this is plausible, it remains speculation. All we have is what Sam knew. There cannot be more.

When he woke up, the rat was looking at him. She was sitting on Magda’s shoulder. She had such pink eyes.

“She likes you,” said Magda. The shop was quiet. He could not hear music or voices.

“What time is it?”

“Half past five. But I thought we should close. We’re both tired. Today was very stressful.”

“True,” he said, and she kissed him. Her mouth did not feel old.

At first he was too surprised to pull back, and then he was not sure he wanted to. That was when she stepped back and steadied Daphne, who had almost fallen.

“Don’t worry,” she said, and smiled. “That was just because of today.”

“OK,” was all he could say.

“I’ll see you next week,” she said.

After she had gone he replayed the kiss. Soon he was thinking of Sinead. It did not matter that she was unstable, obsessive, obviously bad news. Even now, she might be outside. He could go to the window and beckon, and in less than a minute they’d be having sex on the desk. Her teeth biting his lips, his cheek, her nails digging into his back as he pushed into her, harder, faster, till she had come several times, at which point he might start to slow, but she would dig her nails in, tell him not to stop, and this would go on until they were exhausted, perhaps in pain, and only then would he come. It would feel incredible, overwhelming, like a little death. He would lie on her, still inside her, as they softly kissed. Desire would be transmuted from something physical, a basic hunger, into the start of an emotional connection, or better still, the recognition of a bond that had been present, albeit neutered, during all those times he had feigned disinterest. Only with reluctance would he lift himself from her. As he slid off the condom, he’d see it was torn.

Sam did not go to the window to see if Sinead was there. Instead he put the money from the till into the safe. He vacuumed the floor. He turned off the lights. He locked the shop, then walked down the street to where Trudy lived. It was not his usual time, but she was glad to see him.

Sam was there for two hours, but he did not masturbate. He did not remove his trousers or lie on the bed. He spent the time looking at the bruises on her neck, trying to get her to say who had done it, asking her not to see Mr. Asham again. When he offered to compensate her for the loss of earnings, she said she’d think about it. He was on the verge of telling her she needed to leave Comely Bank. Until she was living and working somewhere legally, she would always be vulnerable.

He was about to say this when his phone rang. It was the police. The officer was calling from the shop. “You need to come here,” he said.

Someone had thrown one of the heavy batteries that vehicles used in those days through the window. The floor was covered in broken glass, and the wind had pushed over the displays. Books were strewn over the floor, their pages flapping in panic.

“Was anything taken?” asked the policeman, who looked very cold.

“I don’t think so.”

“Are you sure?”

Sam scanned the books in the window. All of Mr Campbell’s books were present. Except the photo album.

“Nothing’s gone.”

“It was probably just kids,” said the policeman.

Sam had to wait for someone to come and nail a board to the window. He picked up the books and shook them to make sure there was no glass in their pages. As he did, some photos fell from one of Mr Campbell’s volumes.

Both had Mum, 1956 written on the back. Assuming this was Mr. Campbell’s mother (notwithstanding the fact that there was a girl in the picture and Mr. Campbell had been an only child), it seemed unlikely that she could be blamed for any of his failings. These scenes were not from an exceptional day. Such warmth could come only from quotidian kindness. For the child in this picture (and perhaps Mr. Campbell), love was not a treat dispensed on weekends—when there was time, perhaps the will—but a constant star in her sky. She could rely on it. It would not shoot, or fall.

Why shouldn’t a man as horrible as Mr. Campbell have had good parents? The kind of adult you became was not due just to your upbringing. Where you lived, the school you attended, whether you could think or run quickly: All these things could shape you. Every parent made mistakes, was sometimes impatient or cruel, confused their interests with their child’s. But the day could still be saved (and, of course, ruined).

Sam remade the displays, then swept up the glass. The emergency glazier came and boarded up the window.

“Bad luck, eh?” he said, and hammered.

“More like bad karma.”

“Haven’t we all. Can I get a coffee?”

When the glazier left, Sam sat in the dark for a while. He did not want to go home, but the shop was cold from the wind that came past the boards. It was a freezing night, not one to be out in, certainly not for long. It was definitely not a good night to spend by a river under a bridge.

Sam locked the door, buttoned his coat, and went to see a thief.