DURING THAT PENULTIMATE MONTH CAITLIN stopped coming into the bookshop. It had taken her a long time, and it had been painful, but she had finally given up. Any interaction was a risk; the last thing she wanted was hope.

She would have been surprised (and maybe pleased) to know how much her behaviour upset Sam. After all, he was not in love with her, and—though it may seem cruel to say so—they were not really friends. What upset him was the fact that she was leaving. He felt the same when his volunteers left. Though this was usually cause for celebration—it meant they had found permanent employment, true love, a level of self-esteem that made them realise their time was too precious to be spent sitting behind a cash register—it always bothered him. It suggested that his world was not as stable as he thought. This, perhaps, is another reason he stayed in Comely Bank. It was like one of those little lakes a river sometimes leaves behind. A place to meet the same fish all the time.

Sam was especially sensitive because four of his volunteers had left that month. Clive and Penny were the first to go. They announced that with the help of Jesus they had beaten their addictions and in gratitude were going to work with street kids in Bolivia. Next was Mehmet, who clasped Sam’s hand and said he was going to open an ice cream shop in Ürümqi. As for Boring Lesley, she had found a job at the airport. But although Sam would miss them, they were easily replaced. There was no shortage of people in Comely Bank whose lives had hit bottom. Only a week later there were three new volunteers: Abena (who had just converted from Buddhism, her ninth religion, to Islam), Paige (who was on probation), and Douglas (who had had surgery then chemotherapy for his cancer and whose prognosis was good).

But Caitlin meant more to Sam than his volunteers did. One does not have to reciprocate love in order to enjoy it. No wonder he found the loss of Caitlin’s attention distressing. If someone stops loving you, or seeming to love you, it casts a shadow backwards. Treasured Memories lose colour, light, and become Things That Happened. Perhaps she had not enjoyed talking about books or the oddities of their volunteers. Perhaps he had bored her.

Sam started having dreams in which he was continually late. Usually these involved him running to catch a bus because he had gotten the time of departure wrong. When he woke his heart was racing and his chest felt tight; sometimes he had to drink whisky to calm down. The worst part was that he couldn’t disagree with what Caitlin was doing. Anything except ignoring him was basically self-harm.

Sam dealt with the loss of Caitlin’s attention in a way Mrs. Maclean would have understood. He lent Lonnie fifty pounds. He allowed Lucifer to separate Crime from Fiction. On Sunday afternoons he started going to Mrs. Maclean’s house, even though this involved two hours of halting conversation with the three elderly ladies she invited from church. Some days he went to the toilet three times during his visit, just to get away from the talk of bunions and floral arrangements. It was during one of these escapes that he happened to look in a room whose door was usually closed. Inside he could see a writing bureau and a long shelf full of boxes. On that day he went no further; the next week he took as many letters as he could hide in his pockets.

He also tried to be a better housemate to Alasdair. It took three hours to find soybean paste, ginger-marinated tofu, organic spinach, organic flat parsley, wild garlic, freshwater mussels, buckwheat noodles, rice wine, single cream, and saffron. He marinated the mussels for six hours. The sauce took another two. When Alasdair came in he sniffed the air suspiciously, then looked in the pot.

“What’s in that?”

Sam told him, then could not help adding, “It tastes pretty amazing.”

Alasdair picked up a wooden spoon. He dragged it through the thick sauce, then brought it to his mouth. He sniffed.

“No.”

“What?”

“It’s no good.”

“Why?”

“You can’t put these together.”

“Come on. Just taste it.”

Alasdair put his finger in the sauce, then licked it.

“So?”

“It’s very good.”

“I told you.”

“Yes, but that’s not the point. The point is—” he said, and paused, as if he was only then picking a reason. “The point is they don’t work together. The wheat upsets the mussels. The spinach blocks the cream. Just because it tastes great doesn’t mean it’s good for you. You’ll get more nutrition from rice crackers.”

Which is what he ate for dinner.

That same week Sam brought the laptop and image scanner from the bookshop and set them up by the old chest. When Alasdair came in, Sam made no attempt to explain the piles of photos, notebooks, and paper scraps on the floor. Even if Alasdair wasn’t interested, it was a job long overdue. A small fire, a minor flood, and they would all be lost.

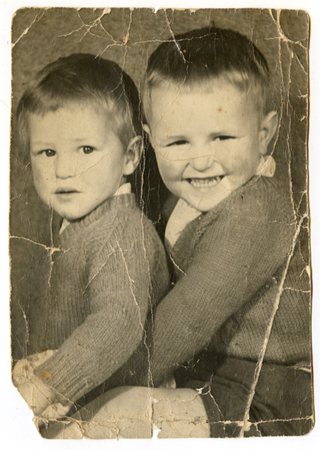

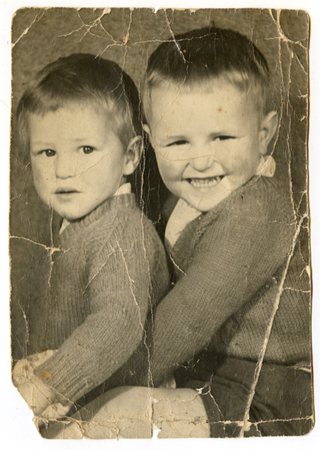

It wasn’t an unpleasant task. He got to remember (or try to remember) when and how he’d found each item. For the first two years he hadn’t bothered to record this information, which meant that some items were even more of a mystery than when he’d first seen them. I doubt anyone will ever know why the boy on the left looks so scared.

Sam didn’t dwell on any picture. He preferred to lose himself in the repetition of the task. Nowadays we only need to hold something up to our screens for a second; back then it could take thirty seconds to scan an item. It was boring, but soothing.

Sam was about to scan a photo he’d found in a book called The Price of Glory, in May 2011, when he realised Alasdair was standing over him.

“I don’t know them,” he said.

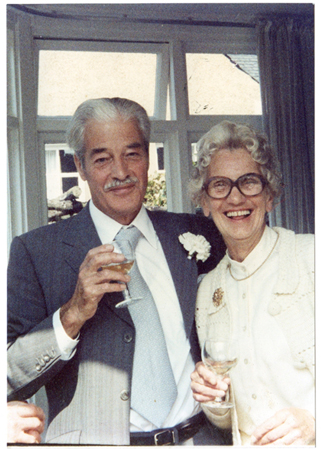

“I didn’t say you did.” Sam turned over the photo. “The women’s names are Val and Cynthia; it doesn’t say what his is. It’s from 1961.”

Sam put it down and picked up another. “You probably don’t know them either.”

“That’s right,” said Alasdair. “They’re not my family.” He squatted and turned over several more photos, then stood and went to the chest.

“You should give these back.”

“I didn’t take them.”

Alasdair thought for a moment. “Maybe you are not a thief. But they belong to someone who didn’t mean to give them away.”

“I thought you didn’t believe in people owning things.”

“These are not things.” He sat down and started looking through the piles. Sam scanned a few more pictures, then yawned. He stood and stretched.

“I’m going to bed. Do you want to take over?”

“All right. Just pass me that cup.”

It was half-full of yellow liquid. At least it wasn’t warm.

That night Sam woke several times and heard the whirr of the scanner. How many people were in that trunk? At least several thousand. More than the number of living people he knew in Comely Bank. Even that small amount, perhaps three hundred, was overwhelming when he considered all the things they’d said and done, what people thought about them. It was a lot of information, most of which would vanish when they died—except that which persisted through their children and friends, and then, after they were gone, through letters, photos, or videos posted on the Internet. For a moment, as Sam lay in the dark, he saw himself in a playground holding the hand of a child with curly yellow hair and a nose like his. He protested, and the child vanished.

The idea of “living on” in others’ memories, and through offspring, was for many a great comfort. Every society has its delusions, some of them necessary. Just because the people of Comely Bank had peculiar notions of how to be happy doesn’t mean we should judge them. Hindsight is too sharp. If someone is writing about us in sixty years’ time, he or she will certainly find fuel with which to burn us. They might, for example, remark on the contradiction between the way we think of the present and the future. As someone who remembers how it was Before, I can attest to the fact that most people now are more focussed on what is happening in the present. We are not always rushing to the next experience, hoping it will be better.

The usual explanation for this shift is that we accept what Sam could not: how quickly things can change, how swiftly they end. Though this is probably true to some extent, it is my belief that most people believe the opposite. Few think that a cataclysm will happen again.

But in ten years, or sixty years, the same thing could happen again, and it might be worse. The world’s population is now smaller and by no means as dispersed. Any thoughts of stopping another cataclysm are only science fiction.

* * *

TOBY BECAME A problem for Sinead in June. She had decided to take him to the park, because the exercise was good for him, and they could stop by the bookshop. He was reluctant to go; in the absence of his hunger, the street had lost its allure.

They did not need their coats. The sky was an encouraging blue.

They walked down the street, past a restaurant, then a café. Toby didn’t even pause. When they passed the delicatessen he glanced in the window, but for only a few seconds. She didn’t even have to stop him reaching for the mangoes and melons arranged outside Mr. Asham’s.

When they reached the bookshop, Sam was on his knees. He was putting new books in the window, the last from Mr. Campbell’s collection, including the photo album. Sinead usually watched Sam from near the kerb, perhaps to preserve the fiction that she was not staring into the window as if it were a television that needed only one channel. On that day, she went to her usual place. Sam had his back to the street, so he did not see her and Toby. This had the advantage of letting her look as much as she wanted, but stopped her from seeing his face. She didn’t bother to take a photo; she had plenty already. For an enjoyable, though average five minutes, she stared at his back and bottom, knowing she would soon be seeing them without clothes. She had tried all the drugs she had bought except gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), a central nervous system depressant said to induce euphoria. A low dose would not put him to sleep, as so many of the other drugs had done to her. Best of all, it was said to remove a person’s inhibitions.

When she saw Sam lean over to put books in the corner of the window, she closed the distance fast. Her hand went into her pocket; she brought out her phone. By the time his shirt had moved up, and his trousers slipped down, her phone was ready to capture the band of flesh revealed. She took a photo, then another, and a third to be sure. Though she had, of course, seen the top of his buttocks before, she had been too dazed, too slow to take a decent picture.

She zoomed in until it seemed there was no glass between them. While Sam was arranging the books he saw a spray of white light on their covers: The flash in her phone had gone off. When Sam turned, she was already moving away.

Sinead and Toby walked quickly down the lane that led to the park. It was as if she were holding a box that contained a present she had been wanting for ages, and so what if she had bought the present herself: The pleasure was no less.

Sean and Rita were on the bench but didn’t see her and Toby. Sean was busy feeding cubes of mango into Rita’s open mouth. Sinead decided that she’d get Sam to do the same for her. She thought of his sticky fingers needing to be sucked.

She steered Toby to a bench under a tree that offered enough shade for her to see the phone screen properly. When she looked at him, he was staring at the ducks and swans. He started to cry.

“What is it? What’s the matter?”

He covered his face with his hands. She didn’t know what else to do but stroke his head. Eventually, his sobs grew quieter. He rested his head on her shoulder.

She kept stroking his hair with one hand, but with the other held her phone. She opened the first picture, which was from farthest away. She stared at the several inches of his skin and it made her feel good, but also bad, because it made her want the real thing more. She moved to the next, which was fractionally nearer, and this gave the illusion of getting closer to him.

Next to her, Toby drowsed and made a whimpering sound. He was such a comfort. Without him she’d be in jail or a mental hospital. She stroked the top of his head and then resumed looking at the pictures that got closer and closer to the skin she would soon be touching. They’d be in bed, and she’d be on top, but only at first, because they’d do everything.

The thought made her close her eyes, and yet she still saw the pictures. If she’d been alone, she might have gotten lost in this fantasy, but Toby was still upset. To quiet him, she smoothed her hand down his hair until it reached his neck. There it lingered, rubbing, kneading, moving blood around.

After a minute of her doing this he went quiet, allowing her to return to the thought of Sam pushing into her. They’d do it until she was sore, or until he passed out, whichever came first. And when she woke, he’d be holding her. Neither would speak; there’d be no need. After a long look they’d kiss. It would be a slow, tender kiss; she’d touch his face, and then her hand would slip down from the neck to his nipples, then down his chest.

When Toby started whimpering, it seemed natural to do the same for him. She didn’t usually do this, but he was so upset there seemed no other choice. The strange thing was that his stomach was so diminished. It was not the stomach of the Toby she had known for the past year, as he was not quite the person she had known for that time. Again, this was unsurprising. She had been wrong to think that Toby might not become someone else. His body had changed, and so had he. As Sinead’s hand moved in circles, she wondered whose stomach she was rubbing. If he was not Toby, then who was he?

This was a troubling thought, one that made her mind and hand seek comfort. She put her hand under Toby’s shirt. His skin was warm, and hairier than she remembered. And it was nice to trace circles on Toby’s stomach, but they seemed abridged. Their natural orbit was wider, several inches more, with the navel at the centre. What stopped her hand, what spoiled the motion, was the top of his trousers. But this problem was like Sam’s reluctance: It was easily overcome. A little powder in his drink, the opening of one button. Beneath Toby’s shirt her hand turned perfect circles. When she was with Sam, on their first morning together, her hand would not stop there. It would travel down between his legs, then be joined by her other hand. His balls would be in one hand, his penis in the other. It would be large, though not at all hard, but that wouldn’t be a problem. There was a special pleasure in coaxing it from that state.

She was beginning to squeeze when Toby groaned into her ear. It was a bovine sound that brought her back to his penis in her fist. She snatched her hand away and stood. He yawned and stretched, and as he did his penis poked out.

“Put it away,” she said, and took a step back. She had passed up hundreds of chances. She wasn’t going to fuck Toby.

But they could be in his bed in five minutes.

“Come on,” she said, and pushed Toby’s penis back into his trousers. She took his hand and dragged him out of the park. When they passed the bench, Sean laughed and whistled the wedding march.

As they turned the corner her heart was beating fast. If Toby didn’t know what to do, she would go on top.

Past the Chinese restaurant, then the dry cleaner. She needed condoms, but the chemist was on the way.

She was in such a hurry she did not see the dog coming out of the bookshop. He had thick black, tufted fur; his name was Mr. Perfect. The fact that he didn’t see her either was not the dog’s fault. He was old and almost blind, and she was going too fast. Sinead’s foot caught his front paw. Mr. Perfect yowled.

“The fuck?” said Lonnie, Spooky’s father, who loved the dog far more than he loved his son. “What the fuck did ya do that for? What did he do to you?”

“Nothing, I’m sorry,” she said, and she was, but she did not want to stop.

“Wait,” he said, and grabbed her wrist. “You need to say sorry to him.”

She looked down at Mr. Perfect. “I’m sorry,” she said, “It was an accident. I just didn’t see him.”

“That’s fine,” said Lonnie, but he did not let go. “Do you want to meet my son?”

She hesitated, not only because the question was unexpected, but also because he had moved his hand up her arm. Only then did she remember how she had almost kissed him.

“Come on,” he said. “He’s just inside.” His hand slid up to her elbow.

“I have to go,” she said, and looked at Toby.

“It’ll just take a minute.”

“No, really, I have to.”

“Why?”

“We need to have lunch.”

“Does he?” Lonnie pointed at Toby’s stomach. His hand crept up further.

I am not particularly sorry that Lonnie did not Survive. If he hadn’t interfered, Sinead would have had sex with Toby. This would have been indefensible. But better than what happened. So what if she fucked him every day for the next six weeks? Yes, it would have been abuse. But Toby would have Survived.

This, then, is why I blame Lonnie: He prevented a lesser evil. Though of course the blame must be shared, and not just with Sinead. On that day, Sam’s mistake was being friendly to her. When he saw her with Lonnie, it was too unlikely a pairing for him to ignore.

“Hey,” he said, and raised his hand. “Do you know each other?”

“Yes,” she said, and smiled. Lonnie looked confused.

“Have you been to the park?”

“Yeah, it was great.”

“Cool,” he said, then Lonnie took his hand off Sinead’s arm. “See you,” he muttered to Sam, then yanked the dog’s leash.

Sinead did not care. She looked at Toby, then back at Sam, and the usual dynamic was reversed. Sam stopped her wanting Toby.

“So what have you been up to?”

She shrugged. “Mostly looking after him. But that’s much easier now. He’s really made progress.”

“I can’t believe how much weight he’s lost. What happened?”

“I don’t know. He just lost his appetite.”

“Amazing,” he said, and she blushed. As if he meant it as praise.

“I guess it’s partly to do with all those cookbooks we buy. I think they’ve really helped. He spends ages looking at them.”

Sam turned away from her. “How do you feel, Toby?”

“OK,” he said.

“Really?”

“Yes.” Toby was not a good liar.

“So are you sticking around this summer?” Sinead asked.

Sam laughed. “Where else would I go?”

“What about on holiday?”

He shrugged. “I don’t even know what that is. I don’t know where I’d go. Anyway, I have a guest at the moment, so I can’t really leave.”

“Who’s that?” she said quickly.

“Alasdair. You must know him. He used to live under the bridge.”

“Cool,” she said.

“So what about you? Are you around this summer?”

“I guess so. Toby and his mum are going away, so I could do that too. But it might be nice to stay here.”

“You should,” he said. “It will be a great summer.”

“Maybe I will,” she said, and turned away. “We have to go now. Toby needs his lunch.”

“All right, see you later,” he said, and seemed sorry she was going. When Sinead got home she wrote in her diary:

June 4, 2017

Today was really horrible and really fucking amazing. I got so turned on in the park I nearly fucked Toby. If there had been any bushes, or it had been dark, I would have done him there. I don’t know what happened. Maybe it was because of the photos. I don’t even know if he could fuck me, but he definitely can get hard. Anyway, I don’t want to think about it. The main, most awesome thing was that when I saw Sam he didn’t do that whole you’re-just-another-person thing. He seemed really pleased to see me! We talked for ages, and I was totally cool, because this disgusting old guy had been perving on me so much that I was too pissed off to throw myself at him. We had this really normal conversation, like we were actually friends. After a while he wasn’t just talking to me, he was actually flirting. It almost makes me think that I don’t need the drugs.

She may have been right. Sam was attracted to her. In his own, stumbling fashion, he was making progress. Given a little more time, he might have stopped being stupid. Perhaps, if there had been an August. If there had been a September.

But she couldn’t wait.

June 6, 2017

Another almost-fuck today. I wasn’t even thinking about Sam. When I got to Toby’s he was lying on his back on the lounge floor, reading a book about cakes. He had his legs open, but I couldn’t see anything because he was wearing baggy tracksuit bottoms and there was no bulge. I thought it was fine, so I sat down next to him and for a while it was OK. We looked at cream cakes and black forest gateau, and even though I was sitting really close I didn’t want him. I was leaning all my weight on one hand, and so when Toby twitched and knocked my arm I fell on him and it was kind of funny. He laughed, and I did too. It was nice to see him happy, and it was nice to be lying on his chest, and so I stayed there. When he started reading again, he rested his hand on my shoulder, and I liked that too so I moved his hand down onto my breast, and after that I lost it. If his mother hadn’t come back, I definitely would have.

After this, Sinead took precautions. She masturbated before going to Toby’s house. She kept him out of reach. Despite these measures, she had two more near misses during the following week. She feigned illness for several days. She considered quitting her job. On June 13 she wrote:

I’m sore, and every time I look at him I think about his cock. But I can’t afford to quit. I need to pay my rent and all the bills and buy more GHB. But if I don’t I’ll probably end up having his baby. I could take out a loan and stay home as much as possible. But I could also start taking the pill and get a new diaphragm. It’s better I fuck him than someone else.

Though Sinead was far from rational, she wasn’t entirely wrong. Both options had advantages. If she quit she’d have more chances to spend time with Sam. They could get to know each other, and then she could drug him.

How bad would it have been if she and Toby had had sex? Though it was morally and ethically wrong, I doubt it would have damaged him much. It might have been upsetting, even traumatising. But he would have Survived.

As for how it would have affected Sinead, that is hard to say. She might have loved it so much she forgot about Sam. It could also have unhinged her further. My guess is that it would have troubled her at first, but after two or three times she would have found ways to justify it. Reasons can always be found.

Sinead’s solution arrived when she was at the dinner table with Toby and his mother. She was trying not to look at him, probably staring at her plate. Despite her best efforts, she glanced at him eventually. She saw his jaw, the saliva on his chin, the mulch of food inside. A disgusting but by no means unfamiliar sight. It was just how Toby ate. Toby, who had been so grotesquely large that she could never want him.

I wonder how long it took her to realise that she’d stopped wanting him. In my experience, this kind of shift happens so quietly it can go unremarked. At the start of my daily walk along the shore I feel so awful I don’t see what’s before me. No fishermen on the wharf, no couples on the beach. There is only a migraine of names and faces that block out the present. Only when I sit down to rest do I notice the palm trees, the green parrots amidst their fronds; only then do I realise I’m feeling better.

Sinead didn’t quit her job. She didn’t fuck Toby. On June 17 she wrote:

This is going to cost me a fortune. I never thought he’d be so picky. At the start he’ll only eat stuff from that delicatessen. I guess it’s what he’s always wanted but never been allowed. Even so, I have to hold the food under his nose and sometimes push it through his lips. But once he’s started eating, there’s no problem. If I switch to cheap stuff he doesn’t seem to notice.

There were, however, difficulties.

Even though I’ve started doing my shopping on the way to his house, I still can’t bring enough food, not without Evelyn getting suspicious. I have to space out the food, which makes it even more expensive, as I need to use the posh stuff to get him going. He loves those little macarons. Pushing my hand away and shaking his head is just for show.

Though Toby (or Toby’s body) had managed to reduce his cravings for food, there were clearly limits to his/its self-discipline, such as being teased with exquisite French sweets. He could not resist such temptation. After two weeks, Toby was ten kilograms heavier. His mother was baffled. She asked Sinead if he’d found money or been hanging round the dustbins.

Losing weight was Toby’s great achievement. He had shown more willpower than Sinead. He had sacrificed a third of his body, his world, in order to save the rest. But this change did not suit her, and so she stopped it, seemingly without remorse. At the end of June she wrote, “It’s great to see Toby getting back to his old self.”