WHEN SAM WOKE HIS HEAD hurt and his mouth was dry. Most of all, there was panic. He was in Sinead’s bed, and he didn’t know why.

He sat up, and the pain was so bad he lay down again. He looked at the clock on the bedside table. It was only nine a.m. Next to the clock was a framed picture of his face. It had been taken in the shop; he was looking right at the camera but not seeing it. He had probably been talking to a customer, but it looked as if he were making meaningful eye contact with the photographer. He didn’t know when the picture had been taken, but it was at least three or four months ago, because his hair was very short. Sinead had been looking at his face each morning for at least that long.

If he’d found a similar picture in Caitlin’s or Malea’s houses, he would have been pleased. Seeing it in Sinead’s bedroom was upsetting. It was only a photo, and far from private, but it bothered him. He imagined Sinead putting it in different rooms, having conversations with it, touching herself while gazing into his eyes. It was invasive and a violation, and it made him furious. At no point did Sam consider the thousands of photos he owned, all without the knowledge or permission of either the people in them or those they had belonged to. If this had been pointed out to him, he would have shaken his head and said, with special vehemence, that it was not the same thing.

As he lay on top of her black sheets he remembered them fucking. Her on top. Then from behind. None of it made sense. After years of self-control, why had he given in? He smashed the photo of his face; it made him feel better.

But there was nothing more twentieth century than thinking you could destroy a piece of information. There would be copies on her phone, camera, and computer; it could be her profile picture; she might have a blog entitled Will I Ever Get to Fuck That Guy in the Bookshop? that featured candid snaps of him from every angle. It had probably already been updated with new and adult content, its title changed to an affirmative.

Sam got out of bed, put on his trousers, and started searching Sinead’s flat. He wanted to know something about the woman he had just slept with. It didn’t matter if she caught him; the worst had already happened.

He began in the bedroom. In the chest of drawers he found sweaters, scarves, T-shirts, underwear, nothing interesting except a small pink box that contained a pair of handcuffs. They were engraved with the message For S from P. You will not want a key.

The wardrobe was more rewarding. He found two shoeboxes full of photos of Sinead on beaches with boys in shorts who looked like they exercised a lot. The earliest photos were from 2006, the last from 2010. None showed her wearing dark colours or with the heavy makeup he was used to seeing. Without the latter, she looked younger, more at ease. There were also birthday and Christmas cards from her parents—though the most recent, from 2013, was signed only by her mother.

The predictable vibrator was in her bedside drawer. Under it were six laminated photos. He saw himself in profile in different places on the street—in Mr. Asham’s, in the post office, in the French delicatessen—with no particular expression. All but one of the pictures were taken from at least ten feet away; the exception showed him at the bus stop, close up, and must have been taken through a bus or car window. There was nothing provocative or suggestive about any of the poses. Whatever she found erotic she supplied herself. Perhaps their banality was the point. These everyday moments were starting points for any fantasy. A chance meeting could lead to conversation, which could segue into a coffee, a beer, his tongue in her mouth.

He looked through the photos again, unsure of whether to take them. Perhaps they did no harm. He was about to put them back in the drawer when he dropped one. He bent to pick it up and saw a notebook with a plain brown cover underneath her bed. Its pages were filled with entries chronicling the last few years. The most recent entry was from the previous week.

July 4, 2017

Still not sure about the dose. Not enough and it won’t work. Too much and he’ll feel sick. It would be so fucking typical if he threw up and passed out.

It made Sam feel both better and worse to know he’d been drugged. He wasn’t to blame; it was basically rape. He sat a moment, letting the thought throb. Then he stood and left the flat, taking the diary with him.

Outside, people were wearing shorts, eating ice cream, and walking very slowly. It was the first day that actually felt like summer. There were expressions of disbelief and sweaters tied around waists. People squinted at the sun as if it were a bright light suddenly switched on. It is probably bad taste to envy those about to die, but in one respect those people in Comely Bank, London, Paris, and New York had something we can never recover. They could look into the sky with absolute trust.

When he got home, Alasdair was hunched over the scanner, holding a photo Sam did not remember. It was a black-and-white picture of a woman wearing a bonnet with ribbons tied under her chin. In her arms she held a small goose, or perhaps a duck, Sam really couldn’t tell.

“What does it say on the back?”

Alasdair turned the photo over.

“It’s blank,” he said, and put it in the trunk. The next item he took from the pile was a notebook bound in black leather.

“Oh, I remember that,” said Sam. “It’s really smoky. There must have been a fire.”

Alasdair brought it to his nose, breathed in, and nodded.

“It’s pretty strange, but also boring. Just this list of things the person bought, it’s really quite path— What are you doing?”

Alasdair’s tongue travelled down the notebook’s spine. When he finished, he said, “This is good.”

“Why the fuck did you lick it? It’s filthy.”

“Because it’s a chemical sense. I wanted to see if it tasted different from how it smelt.”

“And did it?”

“No.”

Alasdair grinned as if he knew a tremendous secret. He opened the book but only glanced at the page before looking back at Sam. His smile was still there, and Sam waited to hear that smoke was good for the body because it contained carbon, or that it was good to lick things because the tongue needed exercise. Instead Alasdair said, “A man came here last night.”

“Who was it? What did he want?” Sam pictured Sean, or Mr. Asham. He thought of Sean holding him down while Mr. Asham hit him.

“He didn’t say who he was. But he looked sick. I think he eats the wrong fruit.”

“What did he want?”

“To give you something.”

Alasdair put his hand under his topmost sweater, then seemed to be feeling his nipple. He brought his hand out, looked at it, flexed his fingers several times, then slid it under a different layer of clothing. He produced a brown envelope.

“Here,” he said, and Sam took it. The envelope was damp.

“Tell him to eat peaches. The best ones are in cans.”

Inside was a small red book with thirty-two pages, most of which were blank. It was Malea’s passport.

The next day, he booked her a plane ticket for the Philippines. The flight was for August 1. He put the passport and ticket through her door that evening. Though Sam would have liked to see Malea’s confusion, then joy, he decided it was best not to give it to her in person. If he was present, it would put too much pressure on her response. There was even a chance she would refuse the ticket, not because she didn’t want it, but to avoid being in his debt. It might even upset her; maybe she’d be angry he’d found out her real name.

But it could also be a chance for them to start again. In another place, where she was not “Trudy,” he could be someone other than Sam who used to pay for sex. Obviously, they’d have to take things slowly, get used to their new roles. It was far from guaranteed. Yet not impossible.

And so he booked himself a ticket on her flight. He did not think there was any need to mention this to her.

* * *

THE LAST TWO weeks in Comely Bank were almost without incident. A black cat called Lucky was rescued from a tree three times, a driver lost control of his vehicle and drove into what had been Mr. Campbell’s antique shop, and a fire broke out in a house near the bridge. Even in the glare of hindsight, none of these events seems auspicious. Only the betrayal, murder, and vicious beating that befell several of the human relics seems to have anticipated the impending cataclysm. Finally, in those closing days, those people were of the present.

It would be a stretch to say that Sam was responsible for all of these mishaps. Yet even the most indulgent view of his actions, from someone who was privy to his every feeling and thought, would find it hard to deny a degree of blame. All that can be said in his defence is that he was badly shaken by his violation. If he hadn’t seen Sinead for the next few weeks, perhaps he might have calmed down. But when he looked out of the bookshop window on July 19, she was on the other side of the street. He stared at her, thinking she would quickly, guiltily leave, but she didn’t seem bothered. In fact she was smiling.

Sam went into the back room and worked his way through twelve bags of novels featuring violent, unhappy men who loved their country so much that they were willing to kill other violent, unhappy men who wanted to harm that country. Though every donation told him something about the people who gave the books, in that particular case all he learnt was that their owners a) enjoyed the idea of global catastrophes being narrowly averted and b) had no respect for books. The spines were broken, the covers loose, the pages water damaged. By bringing them in, the donors had wasted his time and their own. The books would raise no money; no child would be saved. But at least when he went back into the shop, Sinead had gone away.

When she came back that afternoon, it wasn’t a surprise. Having read her diary, he guessed that in her mind this was just another phase of their courtship.

Sam decided he wasn’t going to be angry. A giddy sense of dislocation was starting to build. Now that he was leaving, nothing really mattered. Perhaps his parents had felt the same way before their departure. He wondered how long they had planned it. Whether it had always been an option.

Sinead was back three times the next day, on each occasion for at least forty minutes.

On July 21, she was outside the shop for the whole morning, then most of that afternoon. She wasn’t always looking in his direction. Sometimes she was looking at her phone, most likely at pictures she had taken when he was unconscious. He wanted to take the phone from her hand and smash it on the ground. He wanted to say, “Fuck you, I’m leaving.”

But these were fantasies: If he had really wanted to confront her, he wouldn’t have stayed in the bookshop for an hour after it closed. Only when he saw her walk away so quickly she was virtually running (even stalkers need the toilet) did he dare to leave.

Alasdair was exactly as Sam had left him that morning, lying on the sofa looking at the leather-bound book. It reminded Sam of the way that Alasdair had coveted the photo album. Perhaps it would be best if he sold it as well. They wouldn’t get much for it—it was just a list of things and their prices—but there was a buyer for every book.

Sam took off his shoes. “Why are you still reading that?”

“Because it’s very good. The man knows exactly what he has bought, and how much he paid for it.”

“How do you know it’s a man?”

“By the handwriting. Look.” He thrust the page at Sam.

Date |

|

Item |

|

Price |

June 24 |

|

Bosch dishwasher |

|

£500 |

June 28 |

|

De’Longhi coffeemaker |

|

£300 |

July 5 |

|

Panasonic microwave |

|

£350 |

“Fine,” said Sam, who had a greater objection. “I thought you were against owning lots of things.”

Alasdair tutted. “You know, you can be very obtuse. And I don’t think you’ve read this properly. Listen to this: ‘A Bosch dishwasher, £500. A De’Longhi coffeemaker, £300. A Panasonic microwave, £350.’” He looked at Sam expectantly, then continued. ‘A Bugatti Volo Toaster, £120. A Santos Classic Juicer, £220. A Rangemaster Dual Fuel Range Cooker, £1100. A Bunn coffee grinder’—”

“All right, I get it. This guy loves buying expensive things.”

“No,” shouted Alasdair, and hit the top of the chest so hard that Sam jumped. “That isn’t the point. Why is he listing these things?”

“For insurance purposes?”

“No!” shouted Alasdair. “How can you be so stupid? It’s obvious. He’s making a confession.”

“Of what?”

“That he’s bought a lot of things he doesn’t really want.”

“Perhaps that’s true. But that doesn’t make it a confession.”

Alasdair paused so long that Sam thought he’d conceded the point. When he did answer, it was in the calm, considered way my doctor tells me that eighty-nine is a stupid age to start smoking.

“Do you ever wonder why you’re so curious about other people? Why you enjoy finding things out?” He rubbed his cheek with his palm, then tilted his head to one side. “I think it’s an interesting question.”

“In what way?”

“Because I don’t see how you’re different from the people who buy those books you don’t like.”

“Which ones?” asked Sam, then laughed in a truncated way. “Most of the books we sell are rubbish.”

Alasdair smiled, but in a way that suggested indulgence of an almost parental kind. “The ones about people abused by their priests or stepfathers. What you call ‘misery lit.’”

Sam shrugged. “I don’t see the connection. Those books are bullshit masquerading as autobiography. I’m interested in people’s actual lives.”

“It’s mostly letters and gossip. Just because you do the filling in, the inventing, that doesn’t make it more true.”

“You’ve no idea,” said Sam. “You’d be amazed what I know about some people.”

“What you think you know.”

“What I actually know.”

“Fine. You know that someone’s cheating on their wife. Or that they’re a thief. But that doesn’t explain why you want to know these things.”

“I don’t have to explain myself to you.”

“No, you don’t. But maybe you have some idea.”

“Look, I think people are interesting. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

“But you find some more interesting than others.”

“And?”

“And the people you’re most interested in are the unhappy ones.”

“That’s not true,” said Sam with a trace of anger, because Alasdair seemed so sure of himself. It was insulting to be thought so easy to explain.

“Isn’t it? What about Caitlin? And Toby? That old woman who always looks disappointed? And that couple poisoning themselves. All of them are miserable. Is it, uh, a coincidence”—he paused, as if to savour the word—“that these are the people you’re most interested in?”

Sam had a quick answer. “It’s not because they’re unhappy. It’s because they’re different.”

“Because she wants to be better looking and he eats too much? Because that couple are trying to escape their lives?” Alasdair shook his head. “I’d say they were very normal.”

“What do you know about normal? You used to live under a bridge, and you don’t even know your full name.”

Other than a slight compression of his lips, Alasdair did not respond.

“Your life, if you can call it that, is a mess. And yet you still feel you can tell people how they’re supposed to live. This from a man who drinks his own piss and doesn’t have any friends.”

It felt good to speak freely, and really, Alasdair had it coming. Sam had put up with a lot, more than most people would have. He didn’t see it as being cruel, more a moment of total honesty—and how could that ever be bad? It was OK to temporarily discount the many mitigating circumstances, such as the fact that Alasdair was an amnesiac who was mentally damaged and had little control over what he said.

Alasdair’s response, when it finally came, was somewhat tangential.

“Actually, you’re dying. You have cancer. Right now it’s only in your brain”—he tapped the side of his head—“but very soon it will spread.”

It was a horrible thing to say, but too crazy to take seriously. Alasdair wasn’t finished.

“Instead of trying to get better, you look for people you hope are even sicker. You don’t care about them, and you don’t want to help them. You want to look at their misery and think you’re better off.”

“Shut up,” said Sam, because this was unfair. Being crazy didn’t give Alasdair the right to say anything.

“I have a suggestion,” said Alasdair. “Why don’t you spend time at the hospital? They have people in terrible pain. I suspect you’d find them even more interesting than—”

“Get out. And don’t come back. Go back to your fucking bridge.”

Alasdair did not argue. It took him barely a minute to gather his things. Sam expected him to make some absurd remark, maybe break a window, but all he did was take the front door key from his pocket and place it on the tin chest. Then he turned and left the house, closing the front door quietly.

For the next few minutes Sam stayed in the kitchen, feeling both pleased and ashamed. That these emotions contradicted each other didn’t matter. Neither seemed about to displace the other.

I feel exactly the same when I look out my bedroom window. My eyes start at the horizon, then move down to the waves, which today are a shade between blue and green. After only a few moments I feel a sadness so familiar it is almost without sting. No doubt this dilution stems from a nagging sense of foolishness: Like Trudy (or Malea), I am gazing in the wrong direction, squinting to see what could not be seen even if it were still there.

When I lower my gaze, bringing it towards shore, I am perhaps of two minds already: the foolish and the sad. But to me these are not incompatible; to be foolishly sad is still to feel a single emotion. Only when my gaze reaches land, and people, does a separate emotion begin. Then I feel my breathing slow and my thoughts calm. I look at the people lying on the sand, in couples and small groups, either having sex or watching others; although I can’t see their features from this distance, I’m certain most are happy.

It was much the same for Sam as he stood in his kitchen. He wanted to hear, but also feared, a knock on the door. He felt both relieved and guilty, which made it hard to know what he should do, just as I, when I stand at the window, don’t know whether to turn or keep watching. If the two states alternated, it would be easy to choose. Whilst sad, I could start to turn away from the window. Even if this act was interrupted by my mind switching back to the people on the shore, those few seconds of movement might generate enough momentum for me to ignore this mental reversal. Likewise, Sam, if he had taken a few steps toward the front door, to go after Alasdair to say sorry, might have been able to carry on despite his mind returning to the satisfaction of a house without urine. If only we could be of one mind. Even our unhappiness feels half-achieved.

* * *

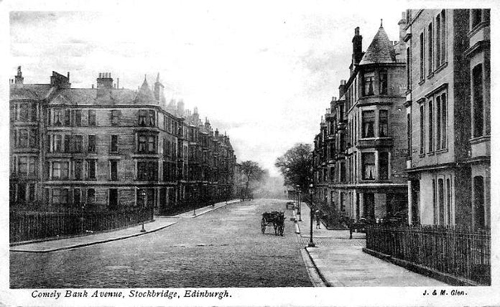

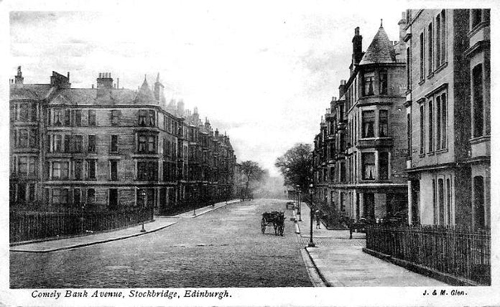

WHEN SAM OPENED the shop the next morning, there was a note from Malea. It was on a postcard that showed Comely Bank as it had been a hundred years before.

All she had written was Thank you, which was both disappointing and entirely expected. At least it was an acknowledgement. He inspected the picture in the hope that this ordinary scene might have been chosen to convey a message. It did not seem promising. The street was without people. The only sign of life was the horse in front of the carriage. If there had been words on shops or street signs, they might have had meaning, but there were just the tenements, their mute windows, the mist blurring the roofs.

He was about to put the card down when he noticed the woman. She stood on the corner, by the carriage, as if waiting for someone. She was going on a journey, and she was not going alone.

This is the danger of pictures. Even when they contain so little, they contain too much.

The rest of the morning passed in a blissful haze of imagining. He saw himself walking with Malea hand in hand through emerald rice fields. They ate noodles at a roadside stall, and she laughed at his failure with chopsticks. He met her family, her friends, and they embraced him, because even though they spoke no English and he was a stranger, they knew he’d brought her home.

The prospect of a new life, in a new place, made everything in the present seem trivial. The large donation of German textbooks, the three boxes of theatre programmes, and the bag of maps swollen with damp were all expressions of people’s disrespect for books and the charity, but because he would not see these things again, they also possessed a minor pathos, just as a man who has had a rash for months or years may find its scarlet patterns pretty once they start to fade.

Sam’s peace of mind was unassailable. When a woman with a bristly chin spoke loudly in Spanish on her mobile phone for ten minutes all he had to do was think of sitting with Malea on a porch at dusk. When a black poodle came into the shop, trotted round the shelves, yawned, then vomited quietly, this did not upset him either. Once again, he thought of himself and Malea sitting outside together, only this time the sunset was a smear of red. He was drinking a beer so cold it made his hand burn; when Malea sighed her breath caressed his neck.

He was able to enjoy this delusion until he saw Toby. His first reaction was fear; Sinead was sure to be with him. He had been stupid to think she would be content with watching him from a distance. This was a woman who saw nothing wrong with drugging someone who had rejected her. Fine, he thought, if she is here, then so be it. Exactly what he meant by this decisive and dramatic pronouncement he did not really know. But he wanted there to be a confrontation in which he was able to throw rocks at her from the moral high ground.

Toby, however, was not with Sinead. He was with his mother. Evelyn had never been in the shop before and seemed bewildered. “Do you know where they are?” she asked, and Toby nodded. They went towards the cookery section, him in front, and there was a slowness to the way she followed, as if she were moving against a headwind. But it was only when two women had to stand aside so Toby could pass that Sam realised he had put a lot of weight back on.

“What about this one?” asked Evelyn, pulling a book from the shelf. “Have you got it already?”

Toby turned the pages, his eyes wolfing down the pictures. Then he shook his head.

“All right,” she said. “You can get one more. And can you please not do that?” she said to a woman who had just unwrapped a chocolate bar.

“What? Why not?” asked the woman, surprised.

“Because it will upset him.”

“I don’t understand,” said the woman, and took a bite. Although Toby wasn’t looking at her, he must have heard the crunch, because he dropped the book he was holding and stepped towards her. She jumped back and shouted, “Fuck!” This reaction was so extreme that several customers laughed, as did Sam, until he saw that Evelyn was crying.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and put her hand over her eyes.

Sam brought her a chair. She sat and dabbed her eyes with a tissue whilst some of the customers stared. The woman whose chocolate bar had been imperilled put her hand on Evelyn’s shoulder and said something Sam did not hear, which made Evelyn nod. As for Toby, he hovered by his mother, shifting his bulk from one foot to the other whilst emitting a whine of distress.

“I’ll be all right,” said Evelyn, then started crying again. Her shoulders shook as she wept.

Toby was almost as upset. He stroked his mother’s hair and began to make a whispering sound that lacked actual words.

“You can’t help it,” said Evelyn. “I know you tried, you really did. You were a very good boy.” She turned her head towards Sam. “He really did try.”

“I know,” he said, then hesitated, thinking she would wonder how he did. But either she wasn’t listening, or she mistook his words for a platitude.

“He was doing so well,” she said. “We were going to visit his uncle in Hong Kong. We were supposed to go next week.”

“And you’re not going?”

“He can’t even go on the bus. Yesterday he put his hand in a woman’s pocket because he’d seen her putting chocolate in there. No,” she said, and wiped her eyes. Sam expected her to continue, but she let the negative stand.

Evelyn stood up and took Toby’s hand. “Have you got your books?” she asked. He nodded, and they walked out slowly, pausing only for Evelyn to say to Sam, “You have a very nice shop.” He could smell gin on her breath.

They had been gone for five minutes before Sam realised they hadn’t paid for the books. It didn’t really matter. The charity couldn’t stop children from being hurt. Taking parents to court, putting kids into care, was merely damage limitation. It wasn’t pointless—it did reduce harm—but however many thousands the charity raised, it could not solve the problem: people.

Sam put the chair back in the corner, then straightened some books. It occurred to him that what Sinead had done to Toby was basically child abuse. Obviously not in a literal sense—although Toby was not fit to look after himself, it was demeaning to his age and experience to label him a child—but more in the sense that he was vulnerable. Like Mortimer, Sinead had abused the trust that had been placed in her. The more Sam thought about what she’d done, how she’d used Toby like an object and by doing so destroyed all he’d achieved and crushed Evelyn’s hopes (both for Toby and herself), the harder he pushed the books into the gaps on the shelves. They made a satisfying noise, like a block of wood being hit by a hammer, a block of wood that deserved to be hit.

Imagine a huge rock travelling though the coldness of space. Imagine that this rock is thirty million miles from Earth. Further imagine that this rock is moving towards the Earth at an average speed of twenty miles per second. At that speed, it will reach the Earth in 1,500,000 seconds, which might seem a lot, but this is only twenty-five thousand minutes, a mere 416.66 hours (which is still more than the number of hours Comely Bank had left when Sam decided he had to get out of the fucking shop).

Even though our imaginary rock is large and travelling fast, it is not unstoppable. All kinds of immovable objects can bring it to a halt, not just major planetoids, but also dwarf planets, trojans, centaurs, and plutinos. Though the stopping of our rock is an exciting prospect—the silent collision, the plume of dust, the shockwaves reaching out—this is only the most dramatic way in which the rock’s heading might change. Many forces can bend or deflect it away from Earth, just as Sam could easily have been delayed from reaching the street. If our rock passed close to any sizable planetoid, it would be subject to its gravitational field, which, if strong enough, might shift the rock’s trajectory towards Saturn, Pluto, or Neptune or through our solar system without any collision at all. If Sam had first met anyone he knew, he would have had to pause for five, perhaps ten seconds; enough to prevent collision.

If she’d been a few steps farther away, he wouldn’t have seen her.

If she’d been a few steps back, she’d have had some warning. She could have smiled, said hi, carried on right past.

But she was right in Sam’s path. Caitlin, who loved him, whom he did not love, who was leaving in four days. The only reason she stopped was that he’d walked into her. There was a moment of non-recognition. Then she knew him. She took a step back, and in that moment, with the sun behind her, he was pleased to see her but also sad, because she was virtually gone.

“Are you all packed?”

“Yes,” she said, and the corners of her mouth twitched. Perhaps she thought of escape. She was looking in his direction, but not directly at him, as if there were someone next to him whom she greatly preferred.

“I’m leaving too,” he said.

She did not seem surprised. “To where?”

“The Philippines.”

“Cool,” she said, but didn’t ask why. She just kept staring to the side of him.

“Well, best of luck,” he said, and immediately felt ridiculous. This was not what you said to someone you were never going to see again (and certainly not someone you had known well). But if Caitlin found this inappropriate, or simply stupid, she hid it admirably.

“You, too,” she said, and then she did smile, a broad, unforced curving of her mouth that spoke as plainly as words. She honestly wished him well.

“Thanks,” he said, and she took a side step, and that was when he saw Sinead. She was outside Mr. Asham’s shop, and she had definitely seen him, because she was holding her phone at arm’s length to take a picture. Having done so, she slowly started towards him.

If the probability of two bodies colliding is so minute, how much smaller are the chances of a third body converging on the same place? Whilst it is possible that Sinead had been waiting there a long time, it was not her habitual spot. Her being there as he stepped towards Caitlin and put a hand on her arm was truly a miracle of the most unfortunate kind.

It is difficult to say how many minds Sam was in at that moment. Perhaps we should start with his best and most basic thought, which was that suddenly Caitlin’s hair was infused with the sun; every strand had an aura that made it singly worthy of wonder. It was not that he was blinded, or couldn’t see her face, just that it was washed in unexpected light. When she had sidestepped, so as to leave, she had moved into a narrow sunbeam, no more than a handbreadth wide, all that could sneak through the luxuriant tree branches (though no match for the trees of Socotra, the “Island of Bliss”). The light was behind her, though not directly, so that the side of her face and the surrounding hair were illuminated—and not just in the sense of being brightened. They possessed a radiance that spoke of deeper enlightenment, a quality present in old religious paintings in which the women were angels or saints. Yet it was a look much older than Christ. When we lived in huts, perhaps even in caves, the sight of sunlight parting a person’s hair must have inspired a similar feeling. What Sam felt was as old as our brain’s ability to perceive beauty. And so there was definitely one healthy reason he leant towards Caitlin.

His lips were two feet from hers when he realised she wasn’t responding. She was as glassy eyed as an animal that perceives danger. It was very confusing. If she wasn’t interested, why didn’t she protest? If she did want to kiss him, why didn’t she lean in?

Over Caitlin’s shoulder he saw that Sinead was only ten feet away. For the last week he had been wondering what she was going to do next. He’d been hoping that his violation had brought her some peace—albeit for his sake, not hers. But the look on her face was enough to disprove this idea. Her front teeth were hurting her lower lip, and she was breathing fast. He saw a level of desire that was akin to fury.

When one first considers the odds of our imaginary rock reaching Earth and the many things that might distort its path, the idea of it doing so seems implausible. But as the hours pass, and the rock continues—close calls with comets notwithstanding—it no longer seems unlikely. By the time the bluish dot of Earth appears, the impact seems fated. The rock will strike our planet; Sinead and Sam must collide.

But the wonderful, terrible truth is that hope persists. A wormhole, a nuclear bomb, the hand of a merciful God. Though salvation now seems as impossible as destruction once did, all those 416.66 hours ago, there is always, no matter how bright the lights in the sky, how tall the tidal wave, that pinch of disbelief.

Sinead was eight, seven, six feet away, close enough to see Sam’s eyes as he kissed Caitlin. He was staring back at a rock that had seemed unstoppable only a moment before. Kissing Caitlin felt amazing, though not because of her mouth. What made it enjoyable was not the way she smelt—like lavender—or her knuckles pressed into his back. It was the broken look of the rock that made him kiss Caitlin as if it were New Year’s Eve and they were drunk and there was fire in the sky. He put his hands on her neck, then smoothed them into her hair; she pressed herself harder against him. She took her mouth from his, but just for a moment, to gasp in air, then they were kissing again. He did not want the moment to end. He wanted to keep kissing Caitlin, and for Sinead to see, for it to hurt in a manner that never became familiar. He wanted it to be a jagged and surprising pain that shifted like the bloody beads of a vicious kaleidoscope. Turning, shifting, opening new cracks in her mind, her heart, wherever pain came from. Sam was glad when Sinead’s hand covered her mouth, pleased when she went pale; when her shoulders dropped he felt satisfied. These reactions, her distress, were certainly revenge, and gratifying, and still not enough. He was disappointed when, with leaden feet, and tears in its eyes, the rock began to reverse. He kept kissing Caitlin even after Sinead ran, just in case she looked back.

Joy is a weaker feeling than hate: It was Caitlin who took her mouth away. She looked at Sam, brought her palm to his cheek, and kissed him very softly. Her tongue did not push through his lips; it explored without entering, flicking left, then right, and Sinead was definitely gone. For several heartbeats there was disbelief, a sense of anticlimax. Then Sam’s body was subject to an intense thrill that resembled an orgasm, but only the way a breeze can be compared to a hurricane. It was the euphoria that follows a victory so implausible, so unexpected, that there is a twitch of embarrassment to the winners’ smiles. Though it would peak, then ebb—which was both regrettable and merciful, because just as one cannot function when in terrible pain, so pleasure can be equally debilitating—the parallel ended there. Though an orgasm can influence how we feel for hours, days, it does not transform us. Only a sense of great deliverance can accomplish that. This has always been so. Those who survived the Black Death, the Holocaust, the Siege of Leningrad might have kept the same names, might have resumed the trades they had practiced before, slept in the same beds with the same people, but they were, each one of them, now cast from different metal.

As for those who say, But we are always changing—and in support of this platitude offer a parable in which a man steps into a river and consumes a kilo of grapes, but when he steps out with only a stalk and all that fruit in his gut, is apparently not the same man—to those people, most of them young, I say: Go ask your parents. Ask your grandparents. See how many say they died on August 2, 2017. The day that, in many cases, is now also their birthday. Whilst I find this adoption of a memorial day entirely understandable, it does mean that people tend not to believe me when I say that this is actually my birthday, and always has been.

I don’t suppose it matters. These days I do little to celebrate; it has been years since I spent an afternoon on the beach, and alcohol gives me heartburn. At my age no one expects some kind of bacchanal, which is doubly a relief. Even if I were capable of such excesses, it seems disrespectful to celebrate on a day when billions died. This was particularly the case during the fifties and sixties when parades and reenactments were still popular, but even now, when the day is marked in more modest fashion, with banners, skywriting, and commemorative films, I feel the same discomfort. This isn’t a common reservation. Lots of people whose birthday is on the second (both originally, and adopted) have no qualms about throwing a large party with musicians that goes on till dawn. The only concession is that they avoid fireworks.

I have friends who roll their eyes when I say that I’m not having a birthday party. “Again?” they ask. “Life goes on,” they say, sometimes in a jocular fashion, but just as often in exasperation.

“Of course life goes on,” I reply. “That’s undeniable. It shouldn’t be any other way. We have to live as fully as we can. But I think 364 days a year are enough for that.”

This answer, or some variant of it, satisfies most of them. Only rarely do I have to go further, like with Shun Li yesterday. She’s having a difficult time right now; her husband is having gene therapy, and it’s not going well. Some of this anxiety was involved in her attack on me. She said my refusal to celebrate had nothing to do with the anniversary. She accused me of being morbid.

I wasn’t having a good day either. My back was very painful. This was why I spoke at length of what I had seen in Manila on my birthday in 2017. After the first meteors hit Europe, everyone was in shock. The streets were lined with cars whose drivers had pulled over when they heard the news. People kept glancing up at the sky. Strangers put their arms round my shoulders, or embraced me fully. I think they saw me as a representative of those former places.

I was in a bar when we heard about the second wave. By then, nobody was paying for drinks; the bottles were on the counter. Many were crying and screaming; the rest stood or sat in small groups, repeating brief phrases I couldn’t understand but guessed were “How terrible” or “I can’t believe it.” We stared at the TV, on which there were satellite images that were just a mess.

When it started raining, I left the bar and walked till I was lost. There was nowhere I wanted to be. I barely registered that I was in a foreign city surrounded by sights and words I did not understand. Only the corporate logos were familiar, though even they seemed strange, not as confident. The rain was hot, and so heavy it stung; when I got tired of walking I lay on the pavement and let it strike my face. Maybe I passed out, but probably not; I don’t think I lost time. When I stood up, it was dark and I didn’t want to be drunk. The city seemed incredibly bright, as if every light that people owned had been switched on, the way children do at night when they’re left alone.

I walked on. At first the streets were broad and lined with apartment buildings with lush, well-tended lawns. Some people passed at a run. Cars were sounding their horns and flashing their lights as if they were returning from a sporting event where their team had won. Soon I heard music, a fast song with heavy bass and a woman singing in Filipino. The music was too loud, distorted. I didn’t want to hear it; I only wanted quiet, but the road I was on led me towards its source. I entered a large square surrounded by grand colonial buildings that had a fountain in its centre, around which were clustered a crowd of perhaps five thousand people, almost all of who were dancing. Most were young, but there were also some elderly people tapping their feet on the margins. A lot of the dancers were drunk, or maybe high, but none seemed deranged, hysterical, or in any way out of control. There were many smiles, frequent laughter; it was one of the happiest crowds I have ever seen.

In hindsight, I can think of many reasons why they were enjoying themselves after finding out that more than a billion had died. For some it must have seemed like the end of the world; if they were going to die, they wanted it to happen whilst they were fully alive. I’m sure that for others the dancing and singing were just an expression of their great relief. It could easily have been Asia that did not exist. There might have been such parties in Paris and New York.

But at the time their joy disgusted me. Though I was too distraught (and drunk) to think clearly, one idea kept repeating like someone jabbing me with a sharp stick: They were celebrating the deaths of everyone I knew. The longer I watched, the more insensitive their party seemed. It was so obviously wrong, so disrespectful; its offensiveness had to be deliberate. They were not content with turning happily away from the disaster; they also wanted to laugh.

If someone hadn’t put a bottle in my hand, I might have left and passed out in an alley.

If I’d been standing somewhere else, I might not have seen those five young men.

But they did, and I wasn’t, so I got even drunker and saw the five young men with their arms around each others’ shoulders. They were between eighteen and twenty-one; each was wearing a cloak. They were facing me, so all I could see of their cloaks was the part around their necks: one was yellow and red, another black and yellow, while the others were red, white, and blue. They were slurring the words of the song they were singing; two had their eyes closed as they swayed back and forth. One of the boys kept blowing a whistle I hoped he’d swallow. They seemed like football supporters because of the way they acted in tandem, chanting and clapping with a coordination that suggested a single mind. When they turned around, they did so in such perfect unison that it was like part of a dance number. That they could do so in such a state of intoxication seems impressive now. But on that humid night all I felt was surprise that quickly shifted to rage. The young men’s “cloaks” were flags that had been tied around their necks. All of them belonged to countries that no longer existed. There was the yellow and black of what had been Germany:

There was the red and yellow of Spain:

As for the red, white, and blue, these belonged to two different countries: Great Britain and the United States of America.

At the time, I did not stop to wonder how these young men had obtained the flags. Did they already have them, and if so, why? Were they taken from outside a hotel or embassy during the confusion? Or had they, during this period of grief and shock, gone to a shop and bought them? At that moment, I had no such questions. For the first time since leaving Comely Bank, I knew what I should do. As I raised my arm, I was certain that this was the only thing I could do.

If the bottle had been empty.

If the boy wearing the flag of my country had kept his eyes open.

But it wasn’t.

And he didn’t.

The bottle broke on his temple.

Glass went into my hand.

My arm.

My cheek.

Then the boy was on the ground.

Two of the flags were clutching their faces; the other two were in shock. We were the epicentre of an enforced sobriety that pulsed through the crowd, taking the attention of one layer of people, which was quickly noticed by those in the next, nothing being more interesting than someone else’s interest. I wish I could say that the sight of so much blood, or the unconscious boy, restored me to my senses. Instead I shouted at the four standing boys, who may not have understood English—though someone within hearing did, because at my trial the prosecution quoted me. Isn’t that funny? is apparently what I said.

Of course, when I told this story to Shun Li this morning, I stopped before this part. The party in the square was enough to make my point.

“Maybe I’m wrong,” I said. “But every year, when my birthday approaches, I remember that music and dancing and feel overwhelmed.”

She was not convinced. She said, “But you still make it to the pier, just like you do every day. If you want to do something special, which isn’t a celebration, why not go in the tunnel tomorrow?”

“I might.”

“Really?” she said, and her laughter seemed unnecessary. It’s not as if I’ve said I’ll never go in. I could go tomorrow. I haven’t decided.

Shun Li and I have different worldviews. She is interested only in what lies ahead. If I told her about Comely Bank and Sam’s last days, I can imagine her response. “What does it matter if sixty years ago a man kissed a girl just so he could hurt another girl?” is what she’d say. She wouldn’t want to hear about Caitlin’s two minds, her fear and evident joy. She’d shrug away the notion that whilst the dead do not live on through us, our feelings for them persist. She might say, in her brusque fashion, that though this is obviously important for the person feeling the happiness, sorrow, or guilt, there is no reason this should matter to anyone else.

For someone like herself, who never knew Sam, Sinead, Alasdair, or Caitlin, they can only be characters in a story; however vivid or interesting they seem, they cannot be real. Their words (“What are you doing?” asked Caitlin) and their actions (she looked at Sam in confusion) will lack resonance for her. If Shun Li did ask, What happened next? it would be with no more interest than she would inquire about a film I had seen (and probably less, Shun Li being something of a movie buff). If I answered this somewhat dutiful question by telling her that Caitlin was as shocked as those flag-covered boys, or that her mouth vacillated between a thin, compressed line of pleasure and a small circle whose bottom half was pulled down as if by spiteful, pinching fingers, Shun Li would nod and say Uh-huh. If I dared add that Caitlin’s next action was to turn her body sharply away from Sam’s, as if she were wrenching it free, then to turn and run away, Shun Li would sigh and turn her gaze to the ceiling. Any further information—that Caitlin then cancelled her flight—would certainly provoke an outburst and her favourite question: Why can’t you just forget?

She has a right to her opinion. I can’t say she’s wrong. My only defence is that every person has their history. We begin as caves, grow into huts, spurt into villages. As adults we are towns, and in some cases, cities.

But however high our towers reach, there are always traces of the stage before. Apart from our parents, our siblings, our cousins, there are friends from school, crushes, bullies, people we have not seen for decades but still think of when we are thirty-eight, fifty-six, ninety years old. Everyone has their relics. Even Shun Li speaks on rare occasions of Gezim, her first husband. No matter how high her skyscrapers (she is without question the finest living guqin player) the spire of their separation remains just as sharp.

Everything is determined by what came before: I am here because of collisions. Because the rock of Sam struck two other rocks, and the impact was pleasing to him. Yet although Sinead’s unhappiness was a kind of revenge, it remained unsatisfying. It was a few hours before Sam found the solution. He opened Sinead’s diary and found the page where she had first written about feeding Toby. After marking the page, he put the diary in an envelope. When he put it through Evelyn’s door the next day, he felt a satisfaction he knew would endure. So what if he was motivated by revenge? It would also help Toby. Sinead would get sacked, then Toby would start losing weight; it wouldn’t be long before he and Evelyn could escape.