THE SUMMER OF 2016 WAS one of the hottest on record. Rain was scarce and fell at night. The dawns were pale and cool. The sun shone without interruption, scorching and relentless. It burned like a ball of fire that seemed to want to drop.

How to describe the light of those endless days? Heavy? Golden? It was both of those things, but also with a quality I have not seen since. It did not simply lie on things—leaves, hair, and pools of water—it went into them. Every shop in Comely Bank had a prosperous glow. The fruit in Mr. Asham’s was perfectly ripe. The old clothes in Caitlin’s shop were mistaken for new. In Mr. Campbell’s shop the coal scuttles and chairs were no longer the contents of dead people’s attics; instead they were already precious relics of some ancient, vanished time. Even the river seemed brighter, faster, rushing like a shining arrow pointed at the future.

And perhaps this is the effect of hindsight: The light before a shadow falls seems brighter in memory. But even allowing for minor exaggeration, these were halcyon days for Comely Bank. You could see it in people’s faces. Whatever else was wrong with their lives, at least they were no longer living beneath clouds. The sky was not a depressing grey. The wind was not a hand that shoved them. For several weeks they spent their free time in their gardens or the park. Their minds were as the sky above: calm, untroubled, clear.

Unfortunately the same was not true for our human antiquities. It was certainly not a time of joy for Toby. During that summer his mother fed him mostly vegetables, which, though they took up the same space on his plate, made him feel only half as full. In compensation, he was allowed to watch more cooking programmes, but these failed to reduce his hunger. He rattled the locks of the kitchen cupboards with such violence that Evelyn had to buy three different kinds of lock before she found one strong enough.

Mrs. Maclean did not enjoy the heat. It made her long for winter.

The good weather also made Caitlin unhappy. It upset her to see so many bare arms and legs, so much undamaged skin.

The sight of so much flesh was also difficult for a young woman called Sinead, who had replaced Mortimer as Toby’s carer. Sinead was tall with dark brown hair and always wore black clothes. There were holes in her ears, lips, and nose through which she sometimes put pieces of metal.

Her problem with so much seminudity was that it made her want to have sex. As an attractive young woman with excellent skin this should have been easy. She could have approached almost any of the men lying on the grass in the park and been sure of success. But she was like one of those strange birds that refuses to fly. She was determined not to have sex; it had been almost a year since her last time.

Why did she deny this healthy impulse? It was certainly not because she felt, as did Mrs. Maclean, that unmarried sex was a sin. By the time she was twenty-nine, Sinead had slept with more than a hundred men, the first when she was fourteen in a classroom at school, the last the summer of 2015. Nor was it because this last experience had been traumatic. In her diary entry for September 2015 she described it as “my most amazing fuck since that time with Pepé behind the funfair.” The problem was that it made her pregnant.

The abortion was unpleasant, but not her first. Perhaps this was why she bled so heavily. They kept her in the hospital for several days, and it was there that she contracted an infection that resisted three courses of antibiotics. During the next three weeks she was so feverish and nauseous she ate almost nothing. She became so weak that there was a morning when she could not get up to go to the toilet. The thought of swinging her legs out of bed, pushing herself up, having to cross the vast expanse of carpet that lay between her and the bathroom: Each seemed a Herculean labour. And so she lay there till her bladder was painful, till it was agony, trying to find the strength to make that impossible journey.

She lay in her sodden bed for hours, smelling the acrid scent of her urine, sobbing her throat raw. Her legs stung. She wanted to die. She would never have unsafe sex again.

By the time she was well, she had lost two and half stone. She had also come to a decision. It was not enough to have “safe sex.” There was no such thing, not completely. Condoms broke, vasectomies failed, the pills could be fakes made in the Philippines. The only way to be sure was not to sleep with a man, not unless it meant something, not unless they were in love. And not in the casual, often drunken, way that made her think she adored, and was adored by, a man she had barely spoken to. Though this might seem an implausible volte-face for someone as promiscuous as Sinead, in her case it can be explained by the fact that almost no one was immune to the idea of true love. Like Mrs. Maclean, she believed that there was someone, somewhere, who was perfect for her.

Her celibacy proved difficult. Within weeks her desire grew to such threatening levels that she was forced to masturbate three or four times a day, always before she left the house. This was a sensible precaution, because during even the briefest outing she was sure to encounter a man who found her attractive. Though she had once welcomed such attention, it was now irksome, invasive, and, most of all, too tempting. Sometimes she dreamed of going under the bridge at night; pushing her mouth against Alasdair’s; feeling the crush of his body on her, the rocks hurting her back.

By the end of 2015 Sinead was leaving her flat only to buy food or go to work. In November of that year she had started working part-time in a small shop next to the delicatessen. The shop was owned by Mr. Campbell’s ex-wife, Stephanie, and sold ceramics, ornaments, polished stones, and jewellery. These items were the result of the “creative flowering” that followed her divorce. Though Stephanie had never previously done any arts or crafts, or expressed a wish to do so, she claimed this was due to the oppressive influence of her former husband. She immediately signed up for classes in pottery, painting, life drawing, jewellery, and sculpture. “It was a wonderful time,” she said to Sinead during her interview. “My teachers were brilliant. They saw what was inside me and helped me get it out.”

Sinead hoped this wasn’t true. The jewellery was ugly. The pots and vases were crooked and squat, the efforts of a child.

Stephanie told her to think of the space as both an art gallery and a shop, “a place to sell things and also to share.” In addition to taking money, Sinead had to act in a curatorial role. To test her ability to do so, Stephanie asked Sinead to pick her favourite piece.

“That’s hard,” she said, then prepared to explain precisely, cruelly why. She definitely did not want to spend days in that tiny room with its orange walls and objects that looked like they’d been made by people with head injuries. It would be fun to see the look on Stephanie’s face, her shock and hurt.

But then Stephanie said, “In what way?” and there was dread in her voice. Obviously some people had already been honest with her.

“Oh, I mean, I just like so much of it. Especially this,” said Sinead, and picked up a ball of lime papier mâché that could only be a paperweight. “It feels so solid. You know it’s really there.”

Stephanie nodded vigorously. “That’s why it’s perfect for dogs.”

The job was better than she expected. There were almost no customers, so there was no temptation. Though the pay was poor, she was free to sit and listen to music or play games on her phone. But after a week of this she was bored and hated all her music. There was nothing to do but stare out the window, and that meant looking at men.

It was only a matter of time before someone caught her masturbating. If it had been a man, this might not have been a problem. He would have probably gotten to have sex with her. Unfortunately, it was Mrs. Maclean, who shut her eyes, then slowly backed out of the shop.

Sinead’s next job was in a coffee shop, where she lasted two weeks, then in a restaurant, where she lasted four days. Her need to spend so much time in the toilet aroused the suspicion of the management, who accused her of avoiding work, and then, when her behaviour worsened (during a seven-hour shift, she had to masturbate four times), of taking drugs.

This was her situation when she saw Toby’s mother’s ad for a carer in June 2016. She had lost three jobs that month. Her groin was constantly sore. She knew she could not keep any job that required her to interact with the public. Which is not to say she had high hopes for this new job: prolonged contact with any male could have only one outcome.

Her first sight of Toby was in his mother’s kitchen. Grotesque, looming, he shambled in, sniffing at the air. She watched him rattle the fridge and cupboard doors, then look in the sink. He was about to plunge his hand into the rubbish when his mother spoke to him sharply. Guiltily, he straightened, looked at the rubbish, then back at her, and only then noticed the dark-haired girl sitting next to his mother.

“This is my son,” she said. Sinead extended her hand. “Nice to meet you,” she said. She did not flinch when he threw open his arms (perhaps confusing meet with its homonym), nor when he threw his arms around her. He held her as tightly as if she’d been a slab of beef.

Their bodies pressed together.

She smelt his sweat.

His groin pushed against hers.

And yet, she felt nothing.

Toby stepped back and smiled. “Very nice,” he said.

“Do you think so?” his mother said, and looked at Sinead, who was trying not to grin. Suddenly even the idea of sex seemed implausible.

“Do you want her to come back?”

“Yes,” said Toby.

“Then she will,” she said.

At first Sinead was not allowed to take Toby out of the house; his mother did not trust a girl who dressed as if she were in mourning. Instead they spent their mornings drawing or painting (his pictures were always of food) or she read to him. She brought a different book each day, but his favourite, which she read many times, was the story of the worm that ate and ate till it was able to fly. Toby did not mind having to stay home. Sinead was pretty and smelt very nice. Sometimes she gave him pieces of paper that had secret pictures. The paper was completely blank till he put paint on it. Then he saw a ship, a dog, an aeroplane, or, best of all, a cake.

Those six weeks were a happy time for Sinead. So long as she was in the house, with Toby, she was safe from temptation, even after seeing him naked. She had been on the toilet when Toby came in. When she yelled at him to get out he said he had to go. As proof of this, he took out his penis. It swayed before her face like some inquisitive snake, and if it had been attached to anyone else (or even to nothing), she would have grasped it. Instead she pointed to the basin then turned on the tap.

Sinead grew fond of Toby. When she stroked his back or rubbed his ears there was nothing sexual about it. There was something remarkable about his dedication to food. It was the source of all his emotions, his happiness and despair. Though she too was consumed by a single impulse that overrode all else, at least she had a degree of control. Toby did not even have that. He was dependent on other people’s decisions about what he could eat. This was certainly for his own good, but it also seemed wrong. Why shouldn’t he be allowed to have what he wanted most? So what if it was going to ruin his health? Maybe it was better for him to be intensely happy for a short time than miserable for years.

Though Toby begged and cried, she didn’t give him extra food. If she did and his mother found out, she’d be fired and end up roaming the streets like a creature in heat. There was also something frightening about the old woman. Sinead could imagine her living in the forest in a cottage made of biscuits and cake. Her son was like a lost child she had overfed.

But there was no question that Toby needed to lose weight. The question was how. Though it was important for him to take walks and be kept away from food, the better method would be to reduce his appetite. The cooking programmes had proved this was possible, but their effects were temporary. What she needed was a way to make him less interested in food. If it had been Mortimer trying to do this, many of Toby’s favourite foods would have suddenly tasted bitter or sour, or Toby would have inexplicably started getting regular attacks of food poisoning. But Sinead genuinely wanted what was best for Toby. As the months passed, and he got fatter and fatter, she began to worry that his heart would burst from having to work so hard.

How different things might have been if Toby’s mother had trusted her less. If Sinead had been forced to spend her days with Toby, at home, until at least the start of 2017, she could have Survived. She might have met some handsome Japanese man. They might have gone to Kyoto that summer.

When Evelyn told Sinead she could take her little boy out of the house, Sinead said she was flattered, very pleased, but perhaps it was too soon. Perhaps Toby wasn’t ready.

“Nonsense,” his mother said. “The fresh air will do you both good. You’re looking a bit pale.”

And so, on a mild morning in July 2016, with the taste of fresh vomit in her mouth—such were her nerves—Sinead and Toby went forth. She was terrified. Her only hope was to get to the park and stay away from men.

Yet within moments of stepping outside she was approached by a man in his sixties who asked what time it was. His name was Lonnie, and he was the father of “Spooky,” one of Sam’s volunteers. Lonnie was not a handsome man. His battered face was the result of many years of heavy drinking and fighting. He was also not to be trusted. When she told him the time he thanked her and lifted his hand to his face so that she saw his watch. She didn’t know if this was an accident, or on purpose, but it didn’t matter. She thought his eyes were very nice, brown and really quite young. She watched his lips curve into a smile. She saw them slowly part. Without thinking, she leant closer, because she wanted to hear what he said. She was certain he was going to say something important, something that showed his interest in not just her face and breasts but also the person she was. Though only a simple utterance, it would be the start of a conversation they would continue for the rest of their lives.

She was about to kiss him when Toby’s throat bulged then loudly delivered gas into her face. And this was not a small detonation. It burst with conviction. After travelling down so many kilometres of intestine, pushing past great boulders of fat, it could not be blamed for announcing its presence. When Sinead looked at Toby’s mouth, his jaw was working, chewing air, his lips flecked with saliva. And though Lonnie’s mouth was ready, it too had saliva, lips, teeth that didn’t look clean. He didn’t want her mouth, just as Toby didn’t want a particular cake but would have settled for any.

And so she stepped away. Lonnie stared in disappointment, then called her a cocktease.

After this she had no problems being out. However inviting the mouth, chest, or buttocks, she only needed glance at Toby to regain control.

The summer of 2016 ended on August 19. On that day the sky dropped so much water it seemed an attack. Toby and Sinead were caught in the rain coming out of the park and ran to find shelter. The first shop was a Chinese restaurant, which was out of the question: The last time Toby had been in a restaurant he had grabbed food from diners’ plates. The next shop was a place that did laundry, but it was closed, so they went into the third. When they wiped their eyes, this is what they saw:

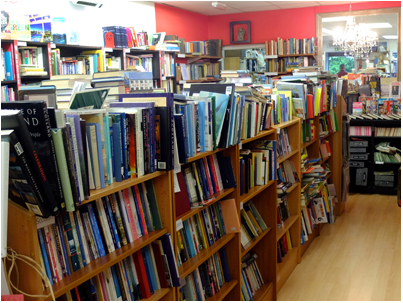

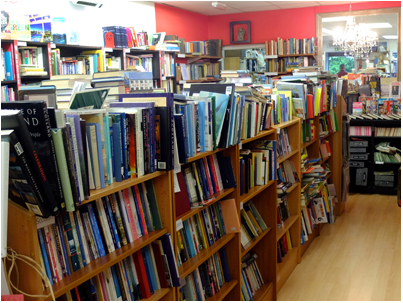

These were the overburdened shelves of Sam’s bookshop, which had many customers, even though there was a library at the other end of the street. The people of Comely Bank were not satisfied with borrowing a book: They wanted to own it.

Sinead and Toby had never been inside; neither was a great reader. After taking a few steps, they paused. Relief gave way to awkwardness. Toby shook himself. Sinead put her hand to her hair. As for what followed, here is Sam’s account.

August 19, 2016

A long, wet day with few rewards, the only exception being two photos in a copy of Macbeth. Both showed a group of young men struggling to bring a small boat in from a rough sea. Despite their difficulties, all appear cheerful. From this I deduce that they were not usually engaged in any kind of manual labour—what made them enjoy the difficult task was its novelty. There are no names or dates on the photos—at a guess I would say they are from the 1930s.

Other than this it was just damp paperbacks with airline tickets as bookmarks. The only diversion was when Toby came in. He wasn’t with Mortimer; he was with a goth girl I haven’t seen before. She had a broken look about her, as if she got slapped awake every morning. I figured they had only come in because of the rain, because at first neither made any effort to inspect the shelves. He stood there like a boulder; her teeth worried her lip. I asked if they needed any help, and this made her smile the way pretty girls smile when they receive the attention that is merely what they deserve. “We’re just browsing,” she said, although they weren’t, and even after saying this she made no move toward the shelves. Instead she stared at my face as if it were hung on a gallery wall. She took a small step towards me, stopped, looked at Toby, and said, “Thanks.” She turned and picked up a book about Japanese swords, leafed through it in a distracted manner, then put it quickly down. “Come on, Toby,” she said. “Let’s find the children’s books.”

She moved down the aisle, past history, past travel, till she reached the kids’ section. I only glanced at her a few times during the next ten minutes, but each time I did, she was looking in my direction, probably to check if it was still raining, which it was. So large was the puddle formed at the crossing that every time a car went through at speed a sheet of water sprayed onto the pavement; two parents with a pushchair got completely drenched.

Though Toby had been well behaved, each time I looked over he seemed agitated. His hands were pressed against his stomach; he opened and closed his mouth while rolling his eyes at her. But the girl ignored him until Toby wailed horribly. He swung his arms like two elephants’ trunks and knocked a pile of books from the shelf. In falling, they struck another pile of books on the shelf beneath, which, in vertical domino fashion, brought down yet another pile. Books were all over the floor. “Sorry,” she said, and bent, which threw the male customers into confusion. The two with girlfriends had to pretend to ignore the spectacle of her upturned bottom, the inch of skin above her waist. The other men took quick visual bites, flicking their gaze away when she straightened. The only one to properly stare was Raymond, who was standing on the kick stool, looking at the erotica section. After the girl had put the books back on the shelf, she led Toby to the cookery section. “Maybe this will make you feel better,” she said, and opened a book.

Slowly the great head turned; for the first time I heard words emerge. “Sausages,” said a high, girlish voice (or perhaps a normal male voice with a liking for helium). “That’s right,” the girl said, and swallowed, and then Toby took the book from her and slowly turned its pages. As he did a light grew in his face, a glow that you see in the faces of child actors in commercials when adult actors pretending to be their parents give them a toy or fizzy drink, and all of them pretend it’s a surprise and that they love each other. The difference was that the light in the elephant’s face was real. I could see this, and so could the girl, who looked at me and smiled, and then her face was more than a mask on which dark makeup had been smeared. The eyeliner and lipstick faded, and I could see that though she was what most guys call “hot,” her face was a palimpsest. Beneath the lips she pushed into a pout, the jaw that seemed clenched, there was someone else. This girl looked out of the goth girl’s eyes like they were holes in a fence. I do not think this girl would have spoken to me, or shown herself, and probably did not know I could see her. But maybe, when she came to the till, she might have taken that chance.

But then Raymond fell from the stool and hit his head, and the girl and Toby just went. Who would have thought the old pervert had so much blood in him?

When I read this, more than sixty years later, what strikes me is not so much his sarcasm, his general lack of compassion, but the way that, for all his intelligence, he had no inkling of how significant this moment was for Toby and Sinead. He can be forgiven for not realising the former; even Sinead, who was usually so sensitive to Toby’s shifts in appetite (which was admittedly a fairly narrow range, consisting as it did of variations of ravenous) was too preoccupied to notice that Toby did not mention food for the next hour. Instead he slowly turned the pages of the cookbook, his eyes consuming each picture.

But Sam also didn’t notice how she looked at him. She wasn’t looking out the shop window. She didn’t care about rain. She was staring at him with an emotion that should have been unmistakable.

That night she wrote in her diary:

August 19, 2016

Could not sleep for thinking about bookshop man. The more I came, the worse it got; I couldn’t stop my hands. After the third time it wasn’t even about the thought of us fucking. It was about us lying together after we’d finished, his head on my breasts. I wanted to stay in this thought forever, to go to sleep with it, but pretty soon it started to fade and the only way to get it back was to imagine us fucking. And I should know better. Perhaps he is married or gay or has a girlfriend or only likes black girls. But I have a good feeling about him.

After this she took Toby to the bookshop every time they went for a walk. As the days shortened and the temperature dropped, she found herself walking past whenever she could—just to glimpse the back of him, sometimes to take a photo with her phone. Though she tried to be patient, to let things build, it was often a struggle.

September 10, 2016

What is the matter with him? He hadn’t seen me for almost a week, but all he said was “Hi.” Didn’t ask where I’ve been or what I’ve been doing. Instead he went into the back room and didn’t come out for ten minutes. I had to buy a book to make him talk to me. I was wearing a black mesh top over a black bikini and although the holes are pretty wide he didn’t glance at my chest once. All he said was “How’s it going?” to which I said OK but that I was really pissed off because I wanted to go and see Damson play in Glasgow but had no one to go with. It was a totally obvious cue, but instead of saying he also wanted to go he started asking about Toby. I told him Toby was fine, that he’d just been to the hospital for some tests, and then I made myself shut up. All we do is talk. Instead I did what I’ve been trying not to. I moved round the counter, not all the way, but far enough so that it was no longer between us. I stared at him. I bit my lip. I could see his eyes through his glasses. Although he must have known that I meant to do or say something, he didn’t seem worried or nervous, and this was very bad. It meant he hadn’t been hoping something like this would happen. It meant he wasn’t one of those guys who pretend they don’t want to have sex because they’re frightened of being rejected. With them you have to do all the work. You have to do the kissing, the asking them back, you have to take off your clothes, and sometimes theirs, before they relax. But all Sam did was look at me in a neutral way.

The next few entries had an uneven tone. Frustration alternated with desire; tenderness gave way to rage. Sinead became convinced that Sam was involved with someone else. Then the journal entries stopped for ten days. When they resumed, it was clear that Sinead had crossed a line.

September 14, 2016

He lives on Royal Circus. No. 24. I don’t know which flat. Either 5 or 6.

September 15, 2016

Definitely no. 5. His name is on the door.

His routine became her routine. She expected to catch him with someone, but he was always alone. But the absence of proof only made her more suspicious.

September 19, 2016

The girl with the fucked-up face was in the shop again. Maybe she does only work next door—but what reason is that to go into the same bookshop twice in one week? She barely looked at the shelves. She talked to him for ages.

Soon she was following Caitlin as well as Sam. She saw her go to the doctor and chemist; she followed him to car-boot sales. But in several weeks of surveillance she never saw them together outside his shop. Though it was obvious to her that Caitlin treasured every second with him—in his presence her face alternated between disbelief and gratitude—her adoration was clearly not requited. He kept her at the same distance that he kept Sinead.