Geoff Upex ran the Land Rover Design Studio in the first half of the 2000s, and the design ‘language’ used on the models of that period was largely his creation.

EARLY DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Things moved very quickly once Ford had taken over control of Land Rover in summer 2000. The American company put in their own Steve Ross as Land Rover’s new engineering chief, and by the autumn there were serious discussions about the way forward. Decisions were quickly taken about key issues, and one of them was that the reliance on BMW engines had to end. Future Land Rover engines were to come from Jaguar, who had of course been in the Ford stable for many years already, and from other Ford-owned sources.

What BMW had known as the L50 and L51 projects were still in existence, but not surprisingly the BMW engineer who had been running them was recalled to Munich. Into the breach as caretaker manager stepped John Hall, who was then in charge of Advanced Vehicle Design. Hall inherited a project that was becoming stale: there were still multiple unresolved issues about costings, and over in the Design Studio run by Geoff Upex there was a similar sense of staleness. Designer Dave Saddington sensed it keenly, and he felt that the problem lay in the perception of the smaller, five-seat model. So he tried an experiment, positioning one of the full-size L50 models between a Range Rover and an existing production Discovery, and masking off some elements of the design with black tape to suggest a new approach to the five-seater model. ‘I tried to get people to think of it as a baby Range Rover rather than as a Discovery minus,’ he explained some years later.

Geoff Upex ran the Land Rover Design Studio in the first half of the 2000s, and the design ‘language’ used on the models of that period was largely his creation.

THE L319 AND L320 PROJECTS

It was an approach that rapidly gained approval, not only within the design team, but also in the wider company beyond. Thinking of the new vehicle as a baby Range Rover ‘automatically put it into a higher price bracket, so there was no longer any need to bring it down to a price. That made for a better business case!’ So instead of two variants of the Discovery, Ford authorized work on the related L319 and L320 projects. L319 became the Discovery 3 (LR3 in the USA) on its release in 2004, and L320 became the Range Rover Sport when it was released a year later.

There was still no reason why L319 and L320 should not share a common platform, and in fact Ford took the idea one step further. At some time in the future Land Rover would have to develop a replacement for the long-running Defender range, and Ford envisaged that this could have yet another variant or variants of the new platform. An option that seemed to have considerable promise was to use the chassis of the then unreleased new Ford Explorer (model U152) as that new platform. Land Rover’s new engineering chief Steve Ross was probably in favour of the idea, not least because he had led the Ford programme to develop it!

However, neither Ford headquarters at Dearborn nor Steve Ross in Britain had any intention of imposing ideas on the Land Rover engineers willy-nilly. So in September 2000, a group of Land Rover’s chassis and packaging engineers flew out to Ford engineering headquarters in Dearborn for a three-month period in which they were to examine this option in detail. They were headed by Steve Haywood, who had run the engineering teams for the first Land Rover Freelander in the mid-1990s and had then been seconded to a Rover cars project (called R30) that was being run from BMW headquarters in Munich. That project was cancelled when BMW sold Rover Cars, and Steve transferred back to Land Rover.

After some careful debate, the Dearborn study group reached the conclusion that the Explorer’s separate chassis would not be suitable for future Land Rovers. Some years later Steve Haywood remembered:

It was too low to the ground. The approach and departure angles were inadequate, and there was insufficient suspension travel. So it would have needed too much new hardware. We also studied the interior package, and the ‘command driving position’ just wasn’t there. Those two fundamentals were too far from the brand DNA, and the platform was too important for Land Rover’s future. So we convinced management that we needed a new platform.

Ford were understandably keen to use the platform of their latest Explorer, coded U152, for the new generation of Land Rovers – but it quickly became clear that this was not going to work. IFCAR/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

A New Chassis

Steve and his team quickly conceived that new platform as a separate chassis – a conservative approach by comparison with the huge monocoque that BMW had approved for the L322 Range Rover, but considerably cheaper and more flexible. Even so, the new chassis was certainly not going to be a conventional design. Instead, it was to be much lighter than Land Rover chassis of old, and was to carry an ultra-rigid monocoque bodyshell that would bear a proportion of the loads that had traditionally been carried solely by the chassis. When this idea was brought to market with the new Discovery in 2004, it was given the name of ‘integrated body-frame construction’ – partly to explain how it worked, but also undoubtedly to make it sound more exciting than it really was.

During December 2000, the new strategy fell into place. Steve Haywood remembered visiting Dearborn that month to make what Ford call the ‘strategic intent presentation’ to the then outgoing Chairman, Jac Nasser. The next twelve months would see the rest of the engineering and design come together.

Steve Haywood was appointed to run the T5 chassis development team, and later took charge of the L319 project that delivered the Discovery 3.

So the Land Rover engineers now had the job of designing and developing a new lightweight chassis that would suit the L319 Discovery, the L320 baby Range Rover and, longer term, the Defender replacement. This was probably known as L321, a programme number otherwise unaccounted for – although Land Rover have never confirmed this, and the programme never became reality. The new chassis took on another new Ford codename and became T5. Just one important design element survived from Land Rover’s brush with the Explorer: this was the ‘portholes’ in the rear chassis side members, which allowed the driveshafts to run through, rather than under, the chassis rails.

Quite early on in the T5 programme the designers realized that the chassis they wanted could not be manufactured using the traditional die-stamping process. They needed quite complex shapes to get the high stiffness-to-weight ratio that was in the plan, and the only way to achieve these was to use the relatively new process of hydroforming. This used water under high pressure to mould metal into the required shape: the blank metal was placed inside a die of the intended shape, and high-pressure water injected behind the metal to force it into the die. Unfortunately there was as yet no plant in the UK where a hydroformed structure as big as the T5 chassis frame could be manufactured.

This was where association with a huge company such as Ford had its merits. The guarantee of large volumes enabled Ford to persuade GKN in the UK, and what was then the Dana Corporation of the USA, to establish a joint venture to build it. The new company was called Chassis Systems Ltd, and in 2002 work began on its new factory in Telford. This was the Dana Corporation’s first hydroforming business in Europe; production began in 2003, and the T5 chassis frames for the L319 Discovery and L320 baby Range Rover were built there using Dana’s patented Robo Clamp process. An additional advantage of hydroforming was that it was actually less expensive than traditional die-stamping.

The first T5 chassis prototypes did not, of course, have the benefit of being made in the new plant. They were instead built rather more laboriously and by hand, and were ready by summer 2001. Land Rover knew them as ‘Attribute Prototypes’ (a term used for prototypes that incorporate proposed elements of a future vehicle), and some were for L320 while others were for L319. They took to the roads for testing straightaway in the form of ‘mules’, disguised under the bodies of Ford Explorers and Mercury Mountaineers. Although some members of the press realized that they must be test prototypes, it was impossible to tell exactly what was being tested without getting close to the vehicle for a detailed examination – and Land Rover took great care to ensure that could never happen.

Prototypes of the T5 chassis were disguised with the bodies of Ford Explorers and Mercury Mountaineers. This ‘Mountaineer’ was pictured during off-road testing in February 2003. JAN PRINS

The main difference between the L319 and L320 Attribute Prototypes was that those for L320 had their suspension tuned to give more sporty characteristics. In its early stages was the ARM system, those letters standing for ‘active roll mitigation’, and the system itself being a further development of ACE (‘active cornering enhancement’), already in production for the Discovery Series II. ACE pioneered the use of accelerometers mounted high up in the vehicle body to detect the onset of roll in a corner, and to instruct hydraulic rams to stiffen the effect of the anti-roll bars. ARM would become part of the Dynamic Response suspension system that was new for L320, and would be standard only on top models.

IT’S A RANGE ROVER

Richard Woolley, who headed the Design Studio team that worked on the vehicle, recalls October 2001 as being the date when the L320 programme kicked off in earnest. The basics of the T5 platform had been settled, and the L319 and L320 programmes had been formally separated. Steve Haywood changed jobs to become Chief Programme Engineer for L319, and Tom Jones was appointed as the Chief Programme Engineer for L320. Nevertheless, the two programmes would always remain linked because of the plan for them to share as much hardware as possible. In fact there would be a much higher proportion of shared components than most buyers of either vehicle would ever appreciate.

While the focus had been on designing the T5 chassis, some preliminary work had been going ahead on both vehicles. For the L320, the benchmarks were seen as the BMW X5, the Porsche Cayenne, and some derivatives of the Mercedes-Benz ML-class, the three models that had created a new market sector for sporty SUV models. However, it was also clear that L320 had to have Range Rover characteristics. It was not to be a competitor for the existing Range Rover, but rather to package most of the Range Rover qualities and characteristics to suit a different target audience. From early on, the key L320 quality was that it was to be sporty and exciting, while the existing Range Rover remained grand and aloof. This distinction also helped to define the boundaries of the L319 and L320 programmes. L320 was expected to stand between the Range Rover and the Discovery in the Land Rover hierarchy.

Size was also to help define the differences between L319 and L320. Following on from the thinking that had gone into L50 and L51 earlier, the L319 Discovery needed a 2,896mm (114in) wheelbase to make room for its three rows of seats. L320, by contrast, continued the thinking about the smaller, five-seat model, and so its wheelbase was settled as 2,743mm (108in) – 152mm (6in) shorter than the Discovery, and – perhaps not entirely coincidentally – the same size as the second-generation Range Rover then in production. The new L322 Range Rover, which would be announced at the end of 2001, had meanwhile been designed with a wheelbase of 2,880mm (113.4in) (Land Rover engineers actually worked in metric dimensions).

Richard Woolley was the Studio Director with responsibility for the design of L320.

There was as yet no formal decision about what the new model should be called, although the focus on sporting qualities quickly led to the use of ‘Range Rover Sport’ as an unofficial description. Others at Land Rover continued to call it the ‘Baby Range Rover’. It would be three years or more before ‘Range Rover Sport’ was finally chosen as the name for the production models.

Considering L320 as a variety of Range Rover had important ramifications in many areas. Land Rover’s marketing people had to create for it a distinctive image that would prevent it from damaging sales of the ‘full-size’ Range Rover, and everything that the designers and engineers working on the development programme did also had to align with that image. It implied a high degree of luxury, of sophistication, and of style, and all of that had to be wrapped up with new levels of sportiness and driving dynamics. Creating L320 in a three-year time-frame was going to be a serious challenge.

SUSPENSION, STEERING AND BRAKES

Land Rovers, Discoverys and Range Rovers had all relied on beam axles until the turn of the century, and the only product from Solihull that had independent suspension was the Freelander, introduced as a 1998 model. It was a core Land Rover belief that beam axles gave far better off-road performance than independent suspension, although the benefits of independent suspension for on-road use were unquestionable. The Freelander had excellent off-road ability for its class, but was well known to be inferior to the bigger Land Rovers off-road, in spite of help from some sophisticated electronic traction aids.

However, all that was about to change. Well aware that the Range Rover could not provide a fully credible challenge to conventional luxury cars if it continued to rely on beam axles, Land Rover were planning to introduce all-round independent suspension on the new L322 Range Rover. In conjunction with air springs – already pioneered on beam-axled Range Rovers – this would give the necessary high levels of ride comfort and on-road handling. However, it would also rely on sophisticated electronics to retain the off-road abilities of a beam-axled vehicle.

Briefly, the issue was this: in rough going, the wheels of a vehicle are often pushed up into the wheel-arches; with beam axles, as one wheel goes up, the one on the opposite end of the axle goes down, helping to maintain tyre contact and traction. With independent suspension, it is possible for both wheels at one end to be pushed up at the same time, perhaps grounding the vehicle in the centre. So for L322, an electronic control system ‘cross-linked’ the air-suspension units when low range was selected for off-road driving, making each pair of wheels behave as if they were linked by a beam axle, so providing optimum tyre contact and traction while minimizing the risk of grounding.

From a very early stage, the engineers working on the T5 chassis pushed hard for independent suspension instead of beam axles. ‘We were about enhancing off-road and vastly improving on-road,’ remembered Steve Haywood. So the T5 team were given access to the new technology being developed for the L322 Range Rover, and drew up their own all-independent suspension system that combined this with double-wishbone suspension hardware at each wheel station. As a result, L320 (and, of course, L319) would have Land Rover’s traditional superb off-road ability, and both ride and handling that were directly comparable to saloon cars, with which it would compete.

Special attention was also given to steering to get the crisp on-road handling that was needed, in particular for L320. The plan was to use a power-assisted rack-and-pinion system, and to mount it carefully so that the vicious kickback that such systems typically produced in rough terrain did not become a problem. However, the system originally chosen proved too quick at speed, and did not have the required agility at low speeds, and so this was changed quite late in the development programme, after the first full prototypes had been built in 2003. Stuart Frith, then running the Prototype Development department at Gaydon, knew from his work on Jaguar projects that ZF could deliver to fairly short time-scales, and suggested that the German company should be asked to come up with a suitable variable-ratio, speed-proportional, power-assisted rack-and-pinion system. The ZF proposal, a version of their Servotronic system, was adopted for production.

All-round independent front suspension was central to the T5 chassis design. This is the twin-wishbone design that was used on the front wheels.

The braking system was built on existing Land Rover practice, with four-wheel disc brakes that had servo assistance, and an ABS system that worked both on and off the road. There were some important novelties, however. Just about to be introduced on the L322 Range Rover was a new type of handbrake mechanism that worked on drums incorporated within the rear discs. This replaced the transmission brake traditional to Land Rovers, and prevented the ‘lurch’ associated with those types if the vehicle was parked on a hill. It was a natural choice for the new models with the T5 chassis.

Also new was an electronic handbrake system that had been developed by Jaguar. Instead of a traditional handbrake lever, this worked by means of a small paddle switch, which freed up space on the transmission tunnel and allowed the designers to produce a more aesthetically pleasing interior. The switch applied the handbrake by means of a servo motor, and disengaged it too – although there was also a system that disengaged it automatically as the vehicle moved away from rest. Successful in Jaguars, this system would go on to give a fair amount of trouble in Land Rover products in the beginning.

One more new feature was introduced specifically for the L320 versions of the T5 chassis. In the plan was an ultra-high performance derivative (which would have the supercharged engine described below), and this was going to need brakes that were more powerful than standard. So for this variant, the T5 engineers decided to use four-piston brake callipers made by the Italian specialist Brembo, with larger-diameter discs on all four wheels.

THE TERRAIN RESPONSE SYSTEM

As Land Rover products became increasingly sophisticated and refined, they also attracted a different group of buyers, and so the company established a market research programme to keep abreast of changes in its target buyers’ tastes and perceptions. From this programme, it became clear that buyers of even the most luxurious models were unwilling to sacrifice the off-road capability associated with the Land Rover name, but that they would appreciate simpler controls for the hardware that made it possible. Many were also well aware that they had not developed the skills to enable them to become competent off-road drivers.

Land Rover acted on this knowledge in several different ways, but there was one way that became an important part of the T5 chassis development programme. This was the design and development of a computer-aided off-road driving system that co-ordinated the vehicle’s systems to provide the best possible traction in different circumstances. The idea was to remove from the driver the responsibility for decisions that needed skill as well as judgement.

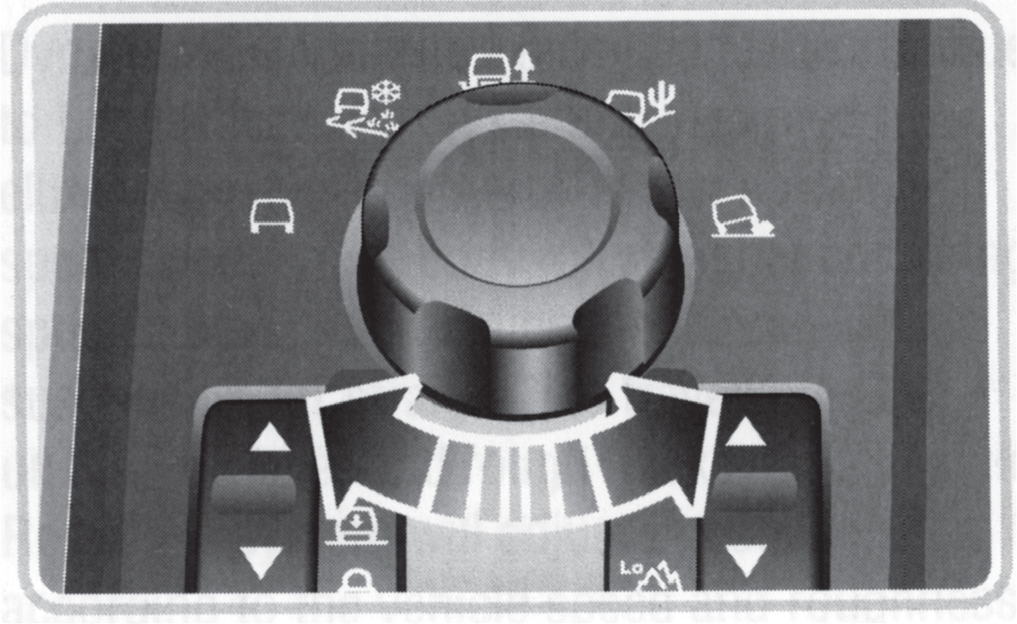

Jan Prins, a Dutch engineer who had come to work for Land Rover, led the team that developed the new system. It became known as Terrain Response, and in production would be operated by a rotary control on the centre console of the vehicle: turning the control to one of a series of icons gave the optimum vehicle response for the type of ground selected. So the accelerator, suspension, gearbox, brakes, ‘Hill Descent Control’ and traction control systems responded differently in ‘rock crawl’ mode from the way they responded in ‘mud and ruts’ mode or in ‘general driving’ mode. The whole system was dependent on the latest data bus technology that linked the various systems involved, and co-ordinated their actions to deliver the best possible traction in different circumstances.

Jan Prins was the engineer behind Land Rover’s groundbreaking Terrain Response traction system.

Ease of use was an important design criterion for L320, and Terrain Response was operated by a simple rotary control on the centre console.

Terrain Response was a superb achievement, but it had, of course, been developed as part of the T5 chassis programme and was therefore specifically intended to work with that chassis. As a result, it was introduced on the models with that chassis – L319 first, and L320 a year later – and it was not until a year after its appearance on L320 that it also became available on Land Rover’s L322 flagship model.

ENGINE DEVELOPMENT

Ford obviously wanted Land Rover to stop using BMW engines as soon as possible. Not only was the German company a rival manufacturer, but appropriate engines could be supplied from within the Ford family of companies for much lower cost. So the engines strategy for L320 was developed as part of a wider strategy that included replacement engines for the L322 Range Rover, and of course, engines for the planned new L319 Discovery.

The obvious source of a new V8 petrol engine to replace the BMW 4.4-litre type in L322 was Jaguar. The company’s AJ-V8 design was still relatively new, having been introduced in 1996, and although all existing production derivatives had capacities of 4.0 litres or less, Jaguar was working on a 4.2-litre block for its next version of the engine. Land Rover’s marketing teams felt that using an engine of smaller capacity than the BMW would look like a step backwards, and so the engine designers were instructed to develop a 4.4-litre block from the 4.2-litre size. A bore increase of 2mm did the trick, wrapped up as part of the programme to make the engine suitable for Land Rover vehicles – where off-road use places unique demands on such things as oil and cooling systems, as well as waterproofing.

All three engines for L320 came from the Jaguar stable. This cutaway shows the 4.4-litre petrol V8 that was central to the range of options…

… and this one shows the supercharged version of the engine that was chosen for use in the top models of L320.

The name AJ-V8 stood for ‘Advanced Jaguar V8’, and the basic engine was an all-alloy, four-camshaft design with 4 valves per cylinder. It was manufactured in a dedicated Jaguar facility located inside Ford’s engine plant at Bridgend in South Wales, and replaced both the long-serving Jaguar V12 engine and the 6-cylinder AJ6 family. The Land Rover version of the engine produced 300bhp – more than the 290bhp of the Jaguar 4.2-litre engine, and also more than the BMW 4.4-litre engine could muster. It was going to be ideal as the core petrol engine for L320.

However, the planning did not stop there. The 4.2-litre V8 would be accompanied by a supercharged version when it entered production in 2002 for Jaguar’s own cars, and this presented very interesting possibilities for Land Rover. A supercharged V8 sounded like exactly the sort of engine that would give L320 a distinctive performance orientation, and it would also be ideal for a flagship version of the L322 Range Rover, which had been intended to have a BMW V12 engine in its top models, but of course would not do so now that Ford owned the company.

So the 4.2-litre supercharged V8 was also given an overhaul to suit use in a vehicle designed to spend time off-road, and it emerged with a power output of 390bhp – vastly more than any production Land Rover had ever had, even though it sounds quite tame by more recent standards.

With the naturally aspirated V8 taking care of the middle of the range, and the supercharged version selected to power the flagship variants of L320, the next job was to find a suitable diesel engine. This would be vital in Europe, where diesel power dominated and large petrol engines were relatively unpopular. Once again, Jaguar came to the rescue, this time with the 2.7-litre V6 diesel that had come about as part of a Ford project run jointly with PSA Peugeot-Citroën in France.

In this picture of the 2.7-litre TDV6 engine, the deep sump designed specifically for Land Rover use is very obvious.

That project had begun with the signing of a joint development agreement in 1998, known as the Gemini project. Ford and Peugeot-Citroën agreed to develop a whole family of diesel engines, and within that family (which were otherwise 4-cylinder types) was to be a turbocharged V6 engine suitable for installation in Peugeot and Citroën models while also being suitable for north-south installation in Jaguars. The result was a world-class multi-valve twin overhead camshaft diesel engine with a cylinder block made of compacted graphite iron. It made its debut in Jaguar’s XJ saloons in 2.7-litre form with twin turbochargers. Ford and Jaguar called it the Lion V6.

Land Rover’s engineers redeveloped it, of course, this time not for the L322 Range Rover, but for L320 and for the L319 Discovery. They redesigned the sump and improved water and dust sealing, added a larger fan to improve cooling for off-road use, and fitted a single turbocharger in place of Jaguar’s two in order to improve low-speed torque for towing and off-road work. What Land Rover called the TDV6 would always be built alongside Jaguar versions of the engine at Ford’s Dagenham engine plant; the Peugeot-Citroën versions were meanwhile built at Douvrin and Trémery in France.

GEARBOXES

Two things were clear from the beginning. One was that L320 was a Land Rover product and would therefore have to have a transfer gearbox with low-range gears to provide the traditional Land Rover off-road ability. The other was that if it was to be a luxury vehicle along the lines of the Range Rover (note that the use of Range Rover in its name had not yet been decided), it would have to have an automatic gearbox as standard. In practice, a manual option seems to have been ruled out early on.

Land Rover had been using automatic gearboxes built by ZF in Germany since the mid-1980s, and there was no good reason to change supplier. The latest ZF offering suitable for the power and torque outputs of the planned engines was a six-speed type, giving smaller increments between gears than earlier designs and therefore smoother functioning. Both fifth and sixth ratios were geared as overdrives, which aided refinement and fuel consumption in high-speed cruising. Known as the 6HP26, this gearbox was chosen for use with all three planned engines.

The drive from this gearbox would be split between the front and rear pairs of wheels by a two-speed transfer gearbox, which in the Land Rover tradition would have a high ratio for everyday driving and a low ratio giving greater control and more hauling power for off-road work. Traditionally, the high and low ratios had been selected manually by an additional control lever, but it was now a Range Rover tradition to use servo motors to do the actual selection of gears, and either micro-switches on the selector lever or a separate switch on the dashboard to activate them. As L320 was being aligned with the Range Rover brand, it would obviously need some form of electric actuation.

The two-speed transfer box chosen was a silent, chain-driven type manufactured by Magna Steyr. This cutaway example shows its interior design.

Interestingly, the engineers working on L319 and L320 decided against using the US-made New Venture NV225 transfer box then planned for the L322 Range Rover. Perhaps they had some inkling that it would prove troublesome in service (its weaknesses turned out to be failure of the front propshaft splines and stretching of the Hy-Vo drive chain). Instead, they chose a transfer box made by Magna Steyr in Austria and known as the DD295 type. The DD295 was another chain-driven gearbox, this time with a bevel gear differential that normally split torque 50:50 front to rear, but it also had a multi-plate clutch pack that could vary that torque distribution and also lock the centre differential. This proved highly satisfactory – and in mid-2005 was adopted for the L322 as well to replace the earlier type of transfer box. Land Rover generally referred to it as the D7u type.

EXTERIOR DESIGN

Immediately after the Ford takeover of Land Rover, Geoff Upex had been appointed as head of the Land Rover Design Studio – the department that had once been known as Styling. Under him were individual studio directors, perhaps best understood as team leaders, and from among them he chose Richard Woolley to lead the team that would work up the body design for L320. Woolley had earlier been with the cars side of the Rover Group, where he had overseen design of the highly acclaimed Rover 75 saloon released in 1998. ‘Our brief was to create an all-new product for Land Rover that embodied Range Rover style in a more compact, sporty package,’ he remembered later.

The initial design sketches for L320 were done in late 2000, before the engineering programme started in earnest. Among them were some by Mike Sampson, which envisaged L320 as a two-door model with a number of design cues from the very first Range Rover of 1970. These included edge-pull door handles, a clamshell bonnet, and even a mock-up of the twin fans behind the grille! Richard Woolley believed that the two-door configuration ‘could epitomise the sporty aspect I was looking for, and help reinforce L320’s individuality among its stablemates.’

Nevertheless, the two-door idea did not last long. Customer research fed into the L320 programme made quite clear that buyers wanted a four-door layout, and so the programme embraced that. But this was to be a very different kind of Land Rover product, and so Mike Sampson proposed what he called a one-and-a-half door layout for each side. There would be a long front door, to give the appearance of a sporty coupé, with a rear-hinged half-size back door. This looked like a flyer for a time, and in fact an engineering package prototype was built on the chassis of a second-generation Range Rover.

Early thoughts by designer Mike Sampson were to make L320 into a two-door, complete with edge-pull door handles like the original 1970 Range Rover. Mike was one of those who favoured the Range Rover Sport name from the start.

The two-door proposal was worked up into a full-size clay model, pictured here under construction in the Design Studio.

By the time it was completed, the two-door clay was wearing ‘Range Sport’ decals on its nose. It looks a little ungainly here, not least because the far side of the model is longer and showcases an alternative design. The front end combines the vertical-bar grille of the original Range Rover with the latest front lamp unit design of overlapping circles.

However, the idea was not pursued. ‘The major problem was building enough strength into the body,’ according to Mike Sampson. ‘It was too risky, and would have been too high an investment for the then predicted volumes.’ So the design team went back to a conventional four-door configuration during 2001, and this idea was in place before the L320 programme as a whole got into gear in October that year.

When customer clinics showed a marked preference for four doors, Mike Sampson drew up this pillarless ‘one-and-a-half-door’ proposal.

This proposal came very early in the programme if we are to believe the date of 2000 on it.

Among the elements shared between L320 and L319 were to be large sections of the inner body structure, and to a degree this sharing dictated what the designers could and could not do. It was never a major hindrance, though, and the L320 design came together as a coherent whole, its sporty nature emphasized by a more raked windscreen than on the forthcoming new Range Rover and by a peak-like rear spoiler at roof level, a feature seen earlier on the Rover 200 hatchback car that had been primarily Dave Saddington’s work.

As this was to be a Range Rover, it had to retain Range Rover styling cues, and yet it also had to have what Upex later called an ‘aerodynamic and muscular exterior design. It had to look dynamic and exciting, and be utterly tempting. We wanted a muscular, hewn-from-the-solid design that promised great power.’

So all these requirements were combined with established Range Rover features such as the floating roof (achieved by combining a body-colour roof with black window pillars) and clamshell bonnet. A more raked screen angle helped to give the necessary sporty look, but in one respect L320 strayed from the established Range Rover norm: a key Range Rover design cue was bonnet castellations, but the design team did not incorporate these in their L320 design. Launch press material suggested that they had been left off to improve airflow, but Geoff Upex’s recollection was more honest: ‘We wanted a smoother, more aerodynamic look,’ he said.

By this stage, L320 was to be a four-door model, but this Mike Sampson sketch shows that the name was still not settled. ‘Range Sport’ was considered, but did not flow as well as Range Rover Sport.

Bold tail-lights, front wing vents, and a lower tailgate finisher with the Land Rover brand name were all carried over to production, but not in quite the form they appear here.

Land Rover had put considerable effort into designing a new ‘face’ for its twenty-first century models, and an important element in that incorporated headlamp units in which round foglamps intersected round headlamps. So a version of this was integrated into the front end of L320, the lamp units flanking a silver-finished grille with three perforated plastic bars, giving a powerful frontal appearance that was imposing but just short of aggressive.

A further link to the Range Rover family came in the shape of front wing vents, although these were quite different from the ‘gills’ used on the L322 model. Instead, Richard Woolley’s team took its inspiration from the wing vents of the high-performance 2001 Bentley Continental R Le Mans, reasoning that this would be entirely in keeping with the sporty flavour of the new Land Rover model!

The need to be subtly different from the ‘full-size’ L322 Range Rover also affected the design of the tailgate, although other factors played their part here as well. The tailgate on L322 followed the Range Rover tradition of a horizontal split into two parts, the lower one hinged downwards to make a platform from which such things as country sports could be viewed. However, L320 was aimed at a more urban clientèle, with no obvious need for such a feature, but a very clear need for maximum convenience of use. So for L320 the tailgate was hinged at the top and lifted upwards on gas struts to give maximum access to the load bay – but it was also designed with a window that could be hinged upwards separately, to provide quick and easy access for small items, such as bags of shopping.

This late sketch by Mike Sampson shows how the production front end would look.

INTERIOR DESIGN

The design of the passenger cabin called for some innovative thinking, because it had to combine Range Rover levels of luxury and finish with a sporting ambience that had never been seen before in any Land Rover product. A further constraint was that the basic architecture of the dashboard could not deviate too far from that of the L319 Discovery, because the two vehicles were to share the same dash armature. The changes had to be made in the foaming on top of that armature, and in the way it was trimmed.

Mark Butler led the interior design for L320. He is pictured here with some interior sketches for LRX, which later became the Range Rover Evoque.

This Mark Butler sketch conveys the high centre console and flowing lines that he wanted to achieve for L320.

The design was done by Mark Butler and Wyn Thomas, initially purely in CAD, and a full-size clay model was only made later in the process. Their approach was to create a cockpit around the driver, and they achieved this with a high, sweeping centre console that gave a totally different feel from the upright arrangement in L319. The switchgear was mounted much higher than in the typical 4×4, giving a more car-like ambience, and the gear selector was also deliberately offset towards the driver to give a sportier feel. Again this contrasted with the L319 solution, where the selector was centrally placed.

Wood trim (with a silver plastic alternative) along the top edges of the centre console hinted at the wood in the L322 Range Rover and was carried across to unique door cards, while the rectangular air vents in the dash were once again distinctively different from the round ones in L319. Only a close and thoughtful look would reveal the similarities of switchgear and instrumentation, and that the two models shared the same steering wheel. The seats, too, were unique to L320, with a supportive design and sporty look that again emphasized the character of the model.

CONSTRUCTION OF THE L320 PROTOTYPES

Design work was still in progress when the first prototypes of L320 were constructed in 2001. These were what Land Rover called Attribute Prototypes – in effect ‘mules’, with some attributes of the planned new vehicle built into existing structures. The T5 chassis prototypes with Explorer and Mountaineer bodies described earlier were simply the first of these.

Full details of all the Attribute Prototypes are not available. However, VU02 RXL was one of them. The ‘top hat’ mounted on the prototype T5 chassis was the body of a red Mercury Mountaineer. The DVLA records show that it was registered as a Ford in May 2002 and had a 4000cc engine – almost certainly the Ford petrol V6 that would be offered in Discovery 3 (L319) models sold in North America.

The Confirmation Prototypes

The next stage was the construction of Confirmation Prototypes during 2003, using the production body design, chassis and running gear. The L320 programme had been timed so that all the major elements of the new vehicle would have been designed and put through basic testing in time for this, and these were the first prototypes that actually looked like the intended production models. They were hand built by the Prototype Division at Gaydon, the same one that had built and run the T5 chassis ‘mules’ disguised as Explorers and Mountaineers.

Discovering precise details of prototypes is always tricky, but it looks as if assembly of the Confirmation batch began in July 2003. A total of seventy-two had been built before the end of the year, and a further (unknown) quantity was assembled in April 2004. The first group of forty vehicles was put on the road in October and November 2003, and went out on test immediately afterwards. The known ones had registration plates that made them look older than they were; they had inconspicuous colours, no badges, and rubber mouldings containing ‘slave’ headlamp and tail-lamp units. These helped to conceal the shapes actually planned for production, but were probably also necessary because no production units had yet been manufactured!

This first group of forty Confirmation Prototypes were given registration numbers in the sequence V251 HHP to V298 HHP, with some omissions. The V-prefix registrations were normally issued between September 1999 and February 2000, but this batch had not been and was allocated to Land Rover (V299 HHP, incidentally, was allocated to a Discovery 3 prototype). In DVLA records, the make of vehicle was shown as ‘Fleet’, presumably by special arrangement to maintain security around the L320 project.

The Confirmation Prototypes had special serial numbers, which are shown in Land Rover records as starting with 000500; the highest number so far discovered is 000573, but the numbers certainly continued beyond that. The VINs contained recognizable elements of the production style, but at least one of them was very odd: it is recorded as 1000SALSEAB415A00052 (which was registered as V298 HHP). The real serial number was probably somewhere between 000520 and 000529, and lost its last figure in the recording process.

Most of these vehicles were painted in white, black or silver; a few were green, and one (V251 HHP) was red. The actual body colour was nevertheless often difficult to discern underneath a ‘dazzle’ type of camouflage that helped to break up the lines of the vehicle when seen at a distance, and so to make spy photography less revealing. Some vehicles also had dummy roof extensions above each body side to suggest the stepped roof of a Discovery.

A Confirmation Prototype pictured on test in the USA. The light units are simply rubber mouldings that contain slave lights, the grille is a dummy, and there is even black masking on the black paint to confuse observers about the real shape. Black fabric covers the distinctive lower door sections, and the wing vent is again a dummy.

Confirmation Prototype V284 HHP pictured during cold-weather tests in Sweden. Once again it has the rubber light units, and this time also a fabric mesh to conceal the grille. Although the wheels are not the ones intended for the top models, it is just possible to see that the front brakes are the Brembo units that were.

V284 HHP again, with the test driver clearly having fun trying out the traction-control systems on snow! The rubber rear lights can be seen here, together with the roof extensions that gave a hint of the Discovery’s distinctive outline.

The Confirmation Prototypes were designed to do exactly what their name suggested: to confirm that the design was satisfactory and ready for production. So they went out on test, and their programme was arranged to meet a deadline of July 2004, when the first volume-production models would begin to come off the lines at Solihull.

It was just as the first Confirmation Prototypes were being assembled that L320’s Chief Programme Engineer, Tom Jones, decided to leave Land Rover. There was a brief interregnum, although without interruption to the test programme that was then under way. Then in summer 2004, Stuart Frith found himself appointed to take Jones’s place at the head of the L320 project. He was a natural choice for the job, having been so closely involved with testing the chassis prototypes earlier, and he carried the programme through to the launch of the vehicle.

Testing of the Confirmation Prototypes between autumn 2003 and late spring 2004 was very thorough, and took place in a wide variety of locations. In Britain there was testing at MIRA, at Land Rover’s own test track at Gaydon, and around its traditional off-road testing ground at Eastnor Castle. Hot-weather testing was done in Dubai, South Africa, Australia’s Nullarbor Plain and California’s Death Valley. Some vehicles went to Canada and Sweden for cold-weather testing and also to fine-tune their performance on ice and snow. The chassis tuning was completed at the Nürburgring and at the Nardo race track in southern Italy. A few spy photographers managed to capture prototypes on film, but by and large the disguise was very successful, and it was hard to see exactly what L320 would look like.

The design was largely on target, but there were some late changes. As explained above, the steering was changed as a result of experience with the first Confirmation Prototypes. Body control was also improved by fine-tuning the body mounts themselves, of which there were ten conventional rubber mounts and four miniature damper units. The final stages involved tuning the dampers and selecting the right tyres to give the on-road characteristics that the L320 team wanted. They worked closely with various tyre manufacturers on this, but Stuart Frith remembered that Continental were particularly good because they were able to turn changes around in five or six weeks, half the time it took other manufacturers.

There are no known survivors of the Confirmation Prototype batch. Most were taken off the road between late 2004 and mid-2005, while the last few perhaps survived until the end of 2005 before being broken up.

Caught on the road close to Land Rover’s Gaydon engineering headquarters, V263 HHP was put on the road in October 2003 and was a 4.4-litre V8 model. Theoretically it was painted silver, although the camouflage makes it hard to work out what is the base colour and what is not!

By the time this Confirmation Prototype, a white diesel dating from November 2003, was pictured on the tank testing ground at Bovington, the production headlamps were available.

WHAT SHALL WE CALL IT?

Meanwhile, L320 still had no official name. There seems to have been some resistance within Land Rover to calling it a Range Rover, as that was the company’s flagship brand and some people felt it should not be diluted in any way. At one point, Land Rover registered the trademarks RS300 and RS400, which were clearly intended to reflect the (approximate) power outputs of L320’s two petrol engines.

Nevertheless, the unofficial name of Range Rover Sport soon gained popularity. Its key advantage was that it was a succinct statement of what L320 was all about. There was also the advantage that the Range Rover name was firmly established and had a resonance that would certainly help sales. But the main sticking point was that word ‘Sport’. Accurate and evocative though it was, it represented a completely new departure for Land Rover, and there were fears that the buying public might not accept it.

As a result, Land Rover mounted a major campaign to sensitize the public in advance of the new model. The first sign of this was in September 2003, when the facelifted 2004-model Freelander was introduced with the option of a new sports suspension and 18in alloy wheels that earned it the name of Freelander Sport – the word ‘Sport’ being carried in highly visible decals that ran across the front doors and wings.

The Range Stormer

The next stage was even more ambitious, and involved the creation of a special show car or concept model that was to be displayed in public a year before the Range Rover Sport actually went on sale. Called the Range Stormer, it was not an early concept for the Range Rover Sport, despite what some commentators have suggested. As Geoff Upex told Nick Hull for Land Rover Design: ‘It wasn’t about the production Range Rover Sport, it was about the Range Rover brand…. We did it to show to the public that this brand isn’t what you think it is, it actually has this other capability of on-road dynamics too.’

Designer Richard Woolley, who oversaw its production, has confirmed that ‘the main intention of the Range Stormer was to gauge public reaction to the idea of a sporty Range Rover.’ Thus it was deliberately built as a standalone project, an eye-catching show car, as part of the plan to sensitize the public to the idea that a Range Rover could have dynamic road performance.

The Range Stormer was a massive success when it was revealed by Land Rover’s Managing Director Matthew Taylor in a dramatic piece of theatre at the Detroit Motor Show in January 2004. ‘In the end it had more coverage than any other car at Detroit,’ Geoff Upex told Nick Hull.

Work on the show car began in May 2003 and was led by Richard Woolley, Studio Director for the real Range Rover Sport, which had already been signed off for production by that stage. To save time, it was built on the chassis of an old-model (second-generation) Range Rover with left-hand drive, shortened to give a 2,700mm (106.3in) wheelbase. The Range Stormer actually had a 4.6-litre V8 engine, and was drivable to the extent that was necessary for a show car.

Design was completed very quickly, and a full-size clay model was ready by August. The exterior design was led by Sean Henstridge with Paul Hanstock in support, and deliberately exaggerated some of the ideas that had gone into L320. However, the Range Stormer was designed with just two doors rather than the four of the production model – doors that were very special indeed, and were designed to add some drama to the ‘reveal’ at Detroit. Each door was in two sections, split horizontally: the top section opened up scissor-fashion, and the lower section folded down to provide an entrance step. The whole system was operated by hydraulics.

Land Rover did not construct the Range Stormer itself, but entrusted the vehicle build to Stola in Turin, a company that specialized in prototype and concept-car construction. The full-size clay went out to Italy in August, while work was continuing on the interior design. This was led by Mark Butler, but also had considerable input from Ayline Koning, who joined Land Rover in September 2003. It incorporated a ‘sports command’ driving position, similar in its effect to the one in the real L320, with a sweeping centre console and a high-set gear selector offset towards the driver.

This ‘teaser’ picture was based on a rendering for the Range Stormer and was released to the press in September 2003 – before the real show car had been completed. The picture was shown to the assembled media during a presentation by Matthew Taylor at the Frankfurt Motor Show that month.

Another design rendering shows the interior concept. The strong centre console running back to the rear seat was not carried through to the production L320.

There were multiple ‘concept car’ features on the Range Stormer, together with several features that deliberately reflected the chosen design for the production L320.

The front seats were another deliberate piece of theatre, designed by Ayline Koning to look as if they were floating inside the cabin. They deliberately resembled a Möbius Strip (a surface with only one side and only one boundary), with the cushion and seat back flowing into the headrest in a continuous line. Built on an aluminium frame, they consisted of four layers of thick saddle leather laminated together on a thin GRP armature. Their edges were deliberately left raw and unfinished to resemble Scandinavian plywood furniture.

The panoramic glass roof, heavily stylized exhaust outlets and rear window spoiler are all clear in this view.

Stola had completed the Range Stormer by December 2003. The finished article had 22in alloy wheels – a size that was quite outrageous for the time – and was painted in a vivid candy-flake metallic colour that was given the name of Oh!Range. Also deliberately theatrical was a huge glass panoramic roof supported on four aluminium cross-braces, a concept that would eventually reach production Land Rover models on the Range Rover Evoque in 2011. The choice of the Range Stormer name was another masterstroke, retaining the link to the Range Rover brand but adding suggestions of dynamics and power.

The Range Stormer did everything that was required of it for the Detroit Show, and after spending some time in the entrance hall of Land Rover’s Gaydon engineering centre, it was handed over to the British Motor Museum at Gaydon. Unfortunately, its dramatic doors no longer function: the hydraulic system was blown by a truck driver who was moving the vehicle, and as Stola had gone out of business by that stage, it has never been repaired.

The interior design was considerably more radical than the exterior – although the exterior was radical in terms of Land Rover design.

Land Rover’s MD introduces the Range Stormer at the January 2004 Detroit Motor Show. The theatrics with the doors were yet to come when this picture was taken.

If the Range Stormer was too obviously a theatrical show car for any thinking person to imagine that it foreshadowed the new model precisely, it certainly did its job of preparing the buying public for a change in Land Rover’s orientation. So when the real Range Rover Sport was announced in January 2005, there was already eager anticipation among those in the market for such a vehicle.

The split-opening door design is clear in this picture taken at the British Motor Museum, where the Range Stormer now has a permanent home. ALLEN WATKIN/WIKIMEDIA COMMONS