Land Rover retained the first production Range Rover Sport. Registered BD55 YZZ, it was a left-handdrive model with 19in V-spoke wheels and was painted Zermatt Silver.

THE EARLY SPORT, 2005–2006

The first line-built Range Rover Sports were assembled in July 2004, and at this point the serial numbers changed from the 000500 sequence used for the hand-built prototypes to the 900000 series that would be used for production models. Nevertheless, it would be several months before production volumes were increased to create a pool of new vehicles for the showroom release in summer 2005. First, a large number of pilot-production models had to be built for validation testing, to prove assembly procedures, and for a variety of other purposes.

Land Rover’s own records suggest that there were no fewer than 301 of these pilot-production models, and that the first ‘full production’ models were assembled in January 2005 to create that pool of vehicles for the Sales Division. The earliest of these was a diesel model with serial number 900302, and by extension all those with earlier numbers must be considered as pilot-production types.

In the meantime, the public relations and marketing teams had begun to prepare the ground for the new model’s release. The first important date in their schedule was 25 November 2004, when UK media were sent a First View booklet, with photographs of pilot-production vehicles and an overview of the new model. In December, further details were released. The Range Rover Sport then made its world debut at the North American International Auto Show in Detroit on 10 January 2005, when Land Rover MD Matthew Taylor was able to follow up on the ‘tease’ he had presented as the Range Stormer a year earlier.

Land Rover retained the first production Range Rover Sport. Registered BD55 YZZ, it was a left-handdrive model with 19in V-spoke wheels and was painted Zermatt Silver.

Back at the Detroit Motor Show in January 2005, Matthew Taylor introduced the real thing – a Supercharged Sport in the First Edition colour of Vesuvius Orange.

The choice of a US motor show for the Sport’s introduction was not merely a question of convenient timing. As customer research for the L320 programme had proceeded, it had quickly become apparent that the really big market for a sporty 4×4 vehicle was in the USA. The introduction of the Porsche Cayenne (a sporty SUV but without the Sport’s off-road capability) to the USA in 2003 had simply served to confirm this, and so the Detroit Show was chosen as the ideal launch platform to gain publicity for the new model in the US market.

A few days later, on 19 January, prices and specifications for the UK market were released, confirming the new model’s position in the Land Rover line-up between the Discovery 3 and the full-size Range Rover. Prices for the Discovery were mostly in the £30,000 segment; the Sport started at £34,995 and went on up to £58,995; and the ‘full-size’ Range Rover started at £45,995 and went on up to £60,995.

The next key date in the programme was April 2005, when the world-wide media launch event was held in Catalonia and journalists from around the world had their first chance to try the new model. This was a Land Rover event, of course, and so a large part of it was devoted to demonstrating that the Range Rover Sport had just as much off-road ability as any other Land Rover, in addition to its new-found on-road performance. The media came away suitably impressed.

The tailgate was a single-piece item with a window that could be opened separately for ease of access to the load area. This Java Black example appears from the exhaust tips and wheels to be a Supercharged model – but it was early enough not to have a Supercharged badge on the tailgate.

Land Rover’s own view of its new model was neatly expressed in a quote attributed to Matthew Taylor and used in press material of the time. ‘We see it as a less frenetic, more refined alternative to existing performance SUVs,’ he said. ‘Yet it is also exceptional off-road, offering better all-terrain ability than any competitor.’ Back at Land Rover headquarters in Solihull, however, there was more excitement about the Sport than this somewhat matter-of-fact statement suggested. The indications were that the new model would appeal to a whole new group of customers and give Land Rover sales globally a significant boost. As things were to turn out, those indications were right on target.

A left-hand-drive Sport is put through some enjoyable off-road driving during the press launch event in Catalonia. The dark grey of the grille and side vents was known as Tungsten, and those are once again the 19in V-spoke wheels.

This kind of road showed the Sport at its best. The model is a left-hand-drive First Edition from the launch fleet.

Showroom sales of the Range Rover Sport began in June 2005, with 2005 model-year vehicles that had been built in the previous six months to give dealers a launch stock. However, production of the 2005 models (identifiable by the 5A code in their VINs) lasted only over the summer. From approximately September, the Sports that left the assembly lines at Solihull were 2006 models (with a 6A identifying code). Not that they had any other significant differences: it was too early yet for Land Rover to make any changes to the specification on the basis of customer feedback. All they could do was adjust the production volumes of individual types and the colour and trim availability to match early indications of what would be popular.

Inevitably, the model line-up for 2005 and 2006 varied from one country to the next, but essentially there were three engines and four levels of trim and equipment. The engines were the 190bhp diesel that was expected to be the top seller in Europe and the UK, the mid-range 300bhp 4.4-litre petrol V8 that was largely intended for North America and the Middle East, and the range-topping 390bhp supercharged V8. Starting from the bottom, the specification levels were known as S, SE and HSE, the top level having no name of its own but being exclusive to the Supercharged models. On top of all this, there was an eye-catching First Edition Supercharged model that had deliberate visual links to the Range Stormer, and acted as a ‘halo’ product that helped to generate valuable showroom traffic.

Distinguishing one model from the next was not particularly easy unless the tailgate badging was visible. Entry-level S models had only a ‘Sport’ designator on the right of the panel; SE and HSE carried the appropriate letters below that badge; and the Supercharged models had a ‘Supercharged’ plaque directly below the Sport name. Supercharged models also had some special distinguishing features: a bright silver finish for the grille bars and side vents instead of the dull Tungsten finish standard on other models, twin stainless-steel exhaust tips, and unique Land Rover logos with silver lettering on black instead of gold on green.

The large and complex tail-lights can be seen here, and so can the HSE model identifier underneath the Sport badge. The grey plastic blob on the roof contained the antenna for the satellite navigation system.

Full frontal: a left-hand-drive First Edition on forest tracks at the launch in Catalonia.

Even though the Sport had been deliberately designed to have dynamic road behaviour, Land Rover had not neglected its off-road abilities. This Supercharged model with standard 20in wheels was pictured on the launch in Catalonia.

A distinctive silver-on-black Land Rover logo accompanied the silver-coloured grille bars on Supercharged models.

These 20in ten-spoke alloy wheels were specified for Supercharged models, when their centre caps also had black-on-silver logos.

The absence of rear identification theoretically would make this an early S model, but the 18in splitspoke alloy wheels seen here were only available with the SE specification.

The two-piece alloy wheels were a rare accessory. They are seen here on a Sport at the 2006 Geneva Show. DRIVELINE CREATIVE MEDIA

The roof bars and roof box on a 2006 model from Land Rover’s press fleet. This was actually a TDV6 with the HSE specification, although it also had the optional 20in ten-spoke alloy wheels.

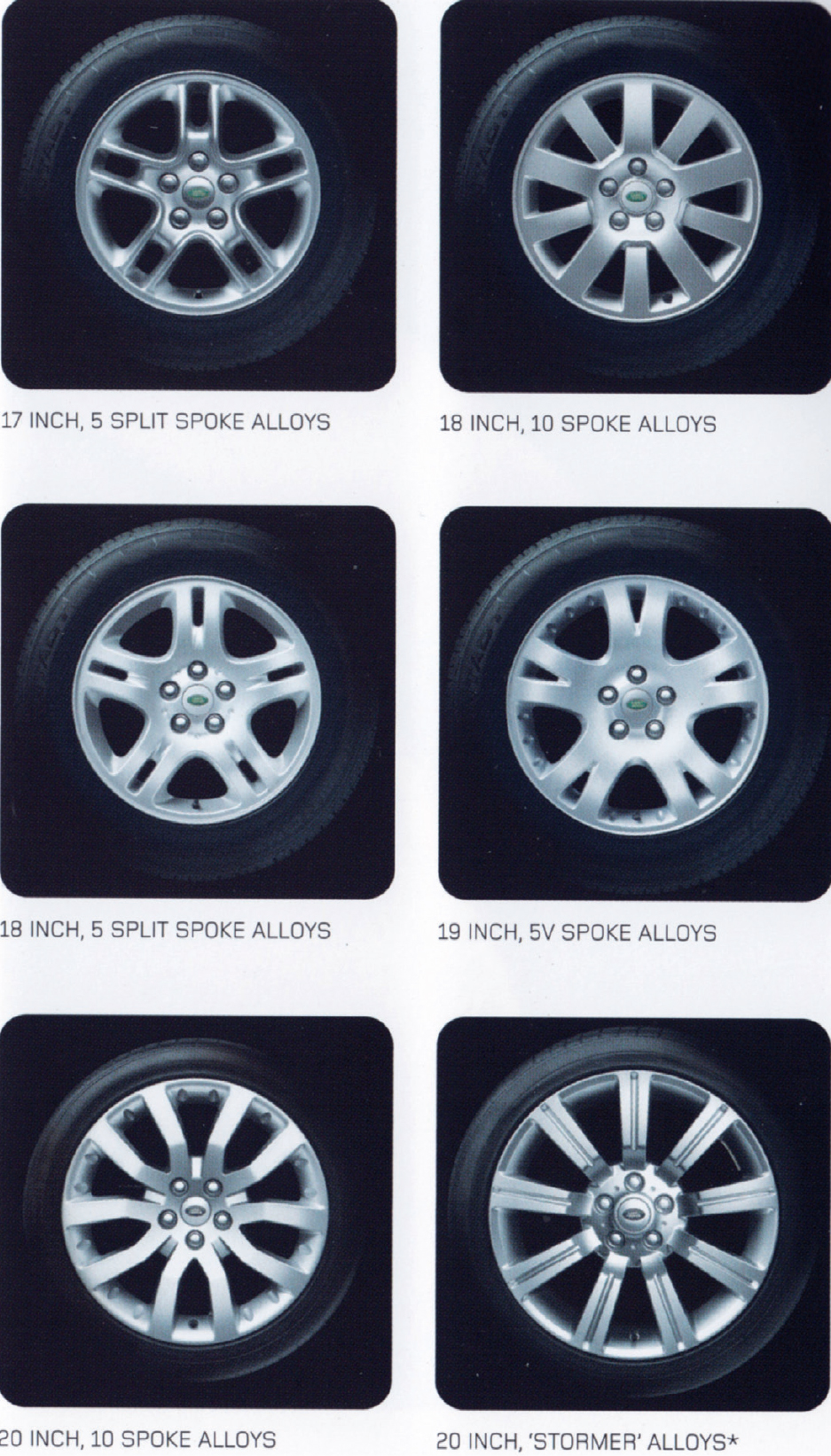

Otherwise the wheel types and sizes were an aid to distinguishing one model from another. The entry-level S models had 17in wheels; there was an 18in size for the SE; HSE models had a 19in size; and the Supercharged models had 20in wheels. Of course, it was possible to order alternatives to the standard-fit wheels, and there was also a special 20in two-piece wheel available as a dealer-fit accessory, and so the wheels were not a wholly reliable way of identifying a Range Rover Sport.

THE TECHNOLOGY

The new Range Rover Sport was unquestionably the most technologically advanced Land Rover yet built, and press officers were more than happy to get that message across to journalists whenever they could. They were less happy to engage in dialogue about why the ‘full-size’ Range Rover did not have some of that new technology, although they would of course have known that Terrain Response and six-speed gearboxes were in the planning stages for introduction a year or so later.

A great deal of the new technology was devoted to giving the new Sport a dynamic on-road behaviour that was worthy of its name. Active roll mitigation was standard on all models. So were ETC (electronic traction control), EBA (electronic brake assist, which applied full braking power automatically if it sensed an emergency) and DSC (dynamic stability control). DSC monitored wheel speed and steering angle to give safer and more stable cornering, and could apply individual wheel brakes to correct over-steer or under-steer and keep the vehicle under control. The Dynamic Response system was standard only on the Supercharged models, sensing cornering forces and compensating for them to give crisper handling; it also decoupled the anti-roll bars when low range was selected in the transfer box to give more wheel articulation for off-road driving.

Then there were E-diffs (electronic differentials) front and rear, which depended on signals from the steering system and the engine to control the power directed to each wheel so that all wheels were supplied with the torque they needed. An active locking rear differential was on the options list, but realistically was not likely to be needed on any model except the Supercharged ones.

The Sport also became the first Land Rover ever to have adaptive cruise control (ACC), and those models that had this option carried a distinctive black plastic plate in the front bumper aperture with the letters ACC. ACC was linked to the standard cruise control system, and worked by using a radar beam to detect the vehicle ahead. It could be set to maintain a chosen distance from that vehicle automatically, and like ordinary cruise control, could be over-ridden by the brake or accelerator pedal.

Topping off the technology on these first models was an optional (and formidably expensive) Bi-Xenon adaptive front lighting system. Not only did it depend on Xenon lighting technology, which delivered a particularly intense light, but it could also vary the amount of light that the headlights cast on to the road to suit the speed and direction of the vehicle. The headlights themselves could move from side to side or up and down to make these variations, and they could follow the curve of the road in exactly the same way as a driver’s eyes.

This discreet black plastic panel betrayed the presence of the automatic cruise control option.

In mid-2005 much of this sounded like technology for technology’s sake – but Land Rover knew what they were doing. Their aim was to create a strong image of high technology around the Range Rover Sport to help give it a distinctive place in the Land Rover model line-up. It was a ploy that proved very successful indeed, and paved the way for the acceptance of high technology features on other Land Rover models later on.

INTERIOR DESIGN

There was no shortage of technology inside the passenger cabin. Every Range Rover Sport came with a dual-zone automatic air-conditioning system that incorporated a particulates filter. For safety, there were altogether eight airbags, including a side curtain bag over each door. Standard, too, was a touchscreen-operated satellite navigation system that worked both on and off the road, and an option was a Nokia voice recognition system for the navigation and audio controls. There was a Bluetooth link to suit mobile phones, too.

There was also an impressive array of in-car entertainment systems. A high quality harmon/kardon audio system was standard on every model, and right at the top of the hierarchy was that company’s LOGIC 7 system that featured fourteen speakers and a twelve-channel digitally controlled amplifier with 50 watts per channel to create a ‘surround sound’ stage in the cabin. Key among these speakers were a centre-fill unit in the dashboard and a 28cm (11in) subwoofer mounted in the tailgate. The LOGIC 7 head unit was integrated within the facia, and was capable of storing six CDs. Being able to play MP3 files on CDs as well gave what Land Rover described as a sixty-six album music capacity – once again a case of technology being used to impress.

For rear-seat passengers there was also the option of a twin-screen DVD system, with a 16.5cm (6.5in) video screen embedded in the rear face of each front-seat headrest. This system was completed by a six-DVD changer mounted in the loadspace.

Beside all this, the question of the interior colour and trim sounds almost unimportant, but the choices did allow considerable variations in the interior ambience, from deliberately sporty to unashamedly luxurious. There was fabric upholstery for the entry-level S models, but all others had leather: plain leather for the SE models, ruched (‘Premium’) leather for the HSE, and a special Sports leather for the Supercharged variants, with perforations and a bright silver backing that could be seen through those perforations.

The high centre console enhanced the ‘cockpit’ feel of the driving position, which is seen here on a Supercharged model with perforated leather upholstery and standard Rhodium contrast trim.

With light-coloured Alpaca upholstery and Cherry Wood contrast trim a completely different interior ambience was created.

This rear seat is upholstered in standard leather, with neither ruches nor perforations. The three head restraints were all adjustable for height, and the seat had a one-third/two-thirds split folding ability to increase the load space.

The electronic handbrake (‘parking brake’ to Land Rover) was operated by the paddle switch nearest the camera. Behind is the rotary control for the Terrain Response system, while the yellow switch engages Hill Descent Control and the other two adjust the suspension height and select low range in the transfer box.

Four upholstery colours were available, and there were multiple possibilities by combining these with contrast trim panels. Mounted on the dashboard and door cards, these were the modern equivalent of wood trim, and indeed there was a Cherry Wood option, which had the effect of giving the interior a luxurious feel. However, the standard contrast trim was Rhodium, a grey plastic that gave a deliberately ‘technical’ feel to the passenger cabin and was entirely in keeping with the Sport’s sporting pretensions.

Rear-seat passengers had their own adjustable airdistribution vents in the back of the cubby box.

THE FIRST EDITION

The First Edition Supercharged model was planned to give the Sport a high profile from the moment the new model reached showrooms. Its orange paint – called Vesuvius – was not the same as the Oh!Range on the Range Stormer show car, but was deliberately similar to it and was not available on any other model. It was also impossible to miss when the First Edition was out on the streets. In theory, the Vesuvius paint was an option, but it seems likely that few First Edition models were ordered without it.

Special wheels, appropriately known as the Stormer design, were also a deliberate reflection of those on the show car, although their diameter was a mere 20in instead of the 22in on the Range Stormer. Like all Supercharged models, the First Edition had a Sports leather interior, but in this case the contrast panels were in Lined Oak, which was not available elsewhere (at this stage) and gave an interesting balance between luxury and sportiness. Land Rover went to some pains to point out that the Lined Oak was hand-polished, but unfortunately this led to all sorts of misnomers in sales and service literature, such as Hand Lined Oak and even Hand Limed Oak. Bright tread strips and Range Rover Sport branded overmats added further special touches.

The overall quantities of the First Edition are not known, but there were just 150 of these special models for the UK, a figure that helped to justify their high cost and made them very exclusive machines.

This press launch picture was quite widely used but is actually misleading. The wheels belong to a standard Supercharged model, but the Vesuvius Orange paint was exclusive to the First Edition, which had different wheels.

ACCESSORIES

Land Rover had learned a valuable lesson with the first Discovery model back in 1989: that a large range of accessories sells well because it allows customers to personalize their vehicles. As the Range Rover Sport was very much a vehicle that customers were going to buy for its individual qualities, the company prepared a large range of accessories to go with it.

Accessories, by definition, were available through Land Rover dealers but could not normally be fitted on the assembly lines. Aftermarket companies soon began to produce cheaper alternatives to some of them, but the typical first owner of a Range Rover Sport tended to go for the genuine factory accessory, which was very often branded with the Land Rover logo.

The accessories available in the early days of the Range Rover Sport are described below.

Wheels and Associated Items

A 20in two-piece five-spoke alloy wheel was available as an accessory fit (note that the V-spoke 19in, ten-spoke 20in and Stormer 20in could all be fitted as line options if they were not already standard on the model). Front and rear mudflaps were available, as were snow chains for the front wheels (only) when 18in and 19in wheels were specified. There was no snow chain option for the 20in wheels.

Exterior Fittings

For protection, there were rubber body side mouldings and a front A-frame (made of black impact-resistant plastic). There were also plastic-coated metal guards for headlamps and tail-lights. A driving- and fog-lamp assembly was available, to fit on the A-frame.

To aid access, there were side steps that fitted below the doors but remained visible as a bright metal strip when the doors were closed. For cosmetic enhancement, it was also possible to buy a chromed top section for the door mirror bodies.

Carrying Equipment

There were multiple options for carrying things on the roof, and central to all of them was a set of roof rails that locked into special receivers. Adding a set of crossbars to these created a conventional roofrack. A luggage box or (smaller) sports-equipment box could be added, as could a ski and snowboard carrier or an aqua sports-equipment carrier. A luggage carrier could also be fitted, and there were optional ratchet straps to secure items to the roof carrier.

A bicycle carrier was also available, but had to be secured to a towbar.

Towing Equipment

Towing equipment varied to some extent from country to country to meet local regulations. In Britain, the options were a multi-height (adjustable) towbar or a quick-release (swan-neck) towbar, in each case with towing electrics. An option was an electrical socket suitable for powering camping equipment.

Interior Enhancements

There were both cosmetic and functional accessory options for the interior. The cosmetic ones were carpet overmats in Alpaca, Aspen or Ebony (although Alpaca was soon deleted), rubber footwell mats, and sill tread plates. A contrast trimpanel kit in Cherry Wood or Lined Oak was available for customers who regretted taking the standard-fit Rhodium trim!

Functional interior accessories were waterproof seat covers for both the front and rear seats, a hands-free phone system, and an add-on rear-seat entertainment system (a system with headrest-mounted screens was a line-build option). This consisted of a foldaway 43cm (16.9in) DVD screen and DVD player, both mounted under the roof, and headphones were available as an extra-cost option.

There were load-space options, too. A metal mesh cargo barrier doubled as a dog guard and came with a useful ‘ski hatch’ so that long loads could still be carried when it was in place. A divider of the same construction could be ordered to split the load space into two – again, suitable if two dogs were being carried and needed to be kept apart. A rubber load-space mat and a rigid load-space protector could be had, plus a waterproof load-space liner. A load retention net with two ratchet straps was a further option, and there was even a sliding load-space floor, which made access to the far end of the load space considerably easier for short people.

There were three add-on child seat options. One was a baby seat secured by the rear seatbelt; one was an ISOFIX child seat, secured by ISO standard fittings; and the third was a child booster seat. All of these were proprietary items that could be supplied through Land Rover dealers.

Extras

Finally there was a miscellaneous group of items that Range Rover Sport owners might find useful. These were not exclusive to the model but were promoted in accessory catalogues for the Sport. They consisted of a foot pump, a first-aid kit, a fire extinguisher, a spare bulb kit, a warning triangle, a tow strap, an electric coolbag and – for lovers of the outdoor life – a day tent that could be supplied at extra cost with a connection tunnel to attach it to the vehicle.

CUSTOMERS AND COLOURS

It soon became apparent that the Range Rover Sport had found a new group of enthusiastic customers for Land Rover. For the most part, these were not at all like traditional Land Rover customers: the off-road capability of the vehicle was very much incidental to the purchase, and the 4×4 drivetrain was seen mostly as providing traction benefits on the road in wet or snowy conditions. These customers were necessarily well off or even wealthy: they wanted and could afford a luxurious vehicle that was expensive to run, but they also wanted a very individualized vehicle that did not have the rather grand associations of the full-size Range Rover.

Brasher and more glamorous than the full-size Range Rover, the Sport was soon adopted by celebrities and others who expected to be noticed. In its early years it attracted a clientèle whom full-size Range Rover buyers sometimes characterized as nouveau riche, and whom many onlookers in Britain characterized – or caricatured – as Premier League footballers. The Supercharged model with its stupendous performance (and cost) was tailored precisely for such people, and the lesser models bathed in its reflected glory.

There were inevitably some people within Land Rover itself who regretted this change of target customer, but they could not argue against the business case that it made for the company. The Range Rover Sport was the single product that helped Land Rover reorient itself towards a fashionable clientèle, allowing prices and profits to increase, and fundamentally changing public perceptions of what the Land Rover name represented.

Car buyers in Britain during the mid-2000s had entered on a period of caution when it came to colour choice. Blacks, silvers, greys and dark blues were in favour, supposedly on the grounds that they were readily acceptable and made a car easier to sell on when the time came. As a result, these were the colours that predominated on the Range Rover Sport, despite the best efforts of the Land Rover designers to provide a range of attractive options.

COLOUR AND TRIM OPTIONS, 2005–2006 MODELS

There were twelve paint options when the Sport was introduced in 2005, of which one was confined to the First Edition Supercharged models. Maya Gold was dropped for the 2006 model-year and Vesuvius Orange had also gone, leaving ten options. All these paints were metallic types except for Chawton White, which was a traditional ‘solid’ type.

In specifying a new Range Rover Sport, customers could also choose from four upholstery colours and two contrast panel options (plus a third that was exclusive to the First Edition). Most combinations were feasible, although Land Rover did refuse to provide some combinations that they considered did not work; in sales catalogues they also highlighted the ones they thought worked best by describing them as ‘designer’s choice’ options.

Premium leather was softer than standard leather and was ruched. Sports leather had perforations, through which a bright metallic backing was visible.

Carpets and Main Interior Trim Panels

The combinations were dependent on the upholstery colour, and were as follows:

| With Alpaca upholstery: | Ebony carpets with Ebony or Ivory panels |

With Aspen upholstery: |

Aspen carpets and panels on SE Aspen carpets and Ivory panels on HSE |

| With Ebony upholstery: | Ebony carpets and panels |

With Ivory upholstery: |

Aspen carpets with Aspen or Ivory panels Ebony carpets with Ebony or Ivory panels |

The six wheel options available at the start of Range Rover Sport production.

Contrast Panel Options

The standard contrast panels were Rhodium, but Cherry Wood was optional at no extra cost. The First Edition, uniquely, came with hand-polished Lined Oak panels.

The HST Model

Aiming to give sales of the Sport a boost over the summer of 2006 before the new 2007 models arrived in the autumn, Land Rover produced another special-edition model based on the Supercharged specification. The Range Rover Sport Supercharged HST (normally known simply as the HST) was announced at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in June, and sales began more or less immediately.

This first HST (there would be another one later) was a 2006 model-year vehicle, even though sales continued into the start of the 2007 model-year. It became the new top model in the Sport range for 2007 in Britain, with a price of £63,000 that put it well into full-size Range Rover territory and made it the most expensive Sport derivative yet. It was, said official literature, ‘Range Rover Sport’s ultimate expression of power and status’. The key feature of the HST was a bodykit that consisted of angular front and rear aprons, a larger tail spoiler, and rectangular tail-pipes. This kit was in turn supposedly inspired by the Range Stormer concept, and it was accompanied by a very full specification.

Land Rover never did explain what the HST designation stood for, but few buyers probably cared. Just five exterior colours were offered: Bonatti Grey, Cairns Blue, Java Black, Rimini Red and Zermatt Silver. The new model came with 20in Stormer alloy wheels and chromed aluminium sidevents, body-colour lower doors and tailgate badge plinth, rear privacy glass (which could be deleted), and an electric sunroof and automatic cruise control as standard. A rear e-differential was standard. Upholstery was the standard Supercharged fare of Ebony or Ivory Sports leather, in either case with Ebony carpets, and the standard contrast trim was Lined Oak.

There were those at Land Rover who freely admitted that they did not like the HST bodykit at all, but there was no doubt that the company had correctly anticipated the way the market would go for the Range Rover Sport. Within the next few months, a number of aftermarket specialists would bring their own bodykits to market to meet a growing demand for a Sport that looked different.

The angular lines of the bodykit designed for the HST model were very much a matter of taste – but they were more tasteful than some of the aftermarket offerings that followed.

The HST also came with twin rectangular exhaust outlets. The correct production Supercharged tailgate badge is also in evidence here.

The Piet Boon Edition

Dutch architect and designer Piet Boon had developed a long-term relationship with Land Rover in the Netherlands, and designed a number of special-edition models for them as a result. In May 2006, the Piet Boon design edition Range Rover Sport was announced, a fifteen-strong special edition based on the Supercharged Sport. It cost €15,000 on top of the price for a standard Supercharged model, which in the Netherlands at that time stood at €108,200.

The key exterior features were Dark Grey High Solid paint, angular exhaust outlets, and roof bars finished in brushed stainless steel. There was a ‘PB Edition’ badge on the tailgate. The seats were re-upholstered with Piet Boon’s own leather, and some interior details were painted black or given a special stainless-steel or alloy appearance. In addition, each example came with an exclusive Piet Boon set of luggage.

A solid paint finish and roof bars in contrasting brushed stainless steel marked out the 2006 Piet Boon edition.

The Range Rover plinth at the bottom of the tailgate was painted in the body colour, and there were Piet Boon identifying badges.

Contemporary design: the exhaust tips had a hewn-from-solid look to them.

LAND ROVER IN 2006

The year 2006 was a busy one for Land Rover, and the success of the Range Rover Sport is best understood against that background. This was a year when the company began in earnest to address environmental concerns associated with its vehicles; and it was a year when it was heavily committed to the second G4 Challenge adventure sports event that promoted its vehicles on a global stage.

Environmental Matters

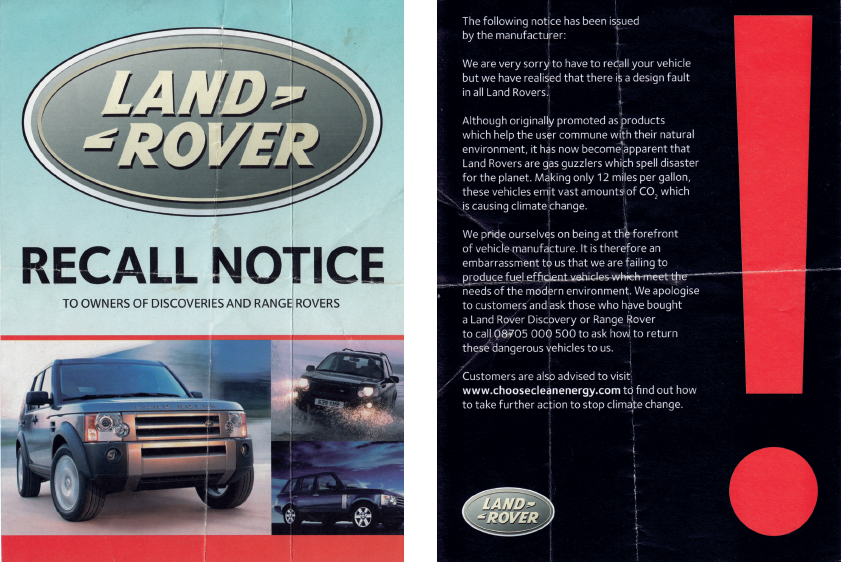

The early 2000s saw a rise in public concerns about environmental damage caused by human activity, and among the activities singled out as particularly damaging was the use of cars. CO2 emissions had been identified as a major cause of global warming, and (beginning in the USA) activists focused on the CO2 emissions in vehicle exhausts – especially in the exhausts of those with large engines.

Inevitably this made Land Rover a target of environmental activists as well. In May 2005, thirty-five protesters identifying with the environmental protection group Greenpeace invaded the Solihull factory and brought production to a halt. Sneaking past security as shifts changed at 7am, they chained themselves to part-built vehicles. After more than a dozen had been arrested for trespass, the remaining protesters left peacefully in mid-afternoon, but not before they had prevented an estimated £3.8 million worth of cars being built.

Land Rover subsequently claimed that they were already working on plans to reduce their environmental footprint, and that they had shown these to Greenpeace representatives before the protest, but clearly to no avail. One way or another, those plans became public knowledge during 2006.

The plans had two dimensions. On the one hand, Land Rover was working on a suite of new technologies for future vehicles that would reduce their environmental impact. However, the company was well aware that no amount of investment could speed up development of these new technologies to match the perceived urgency of the problem. So in parallel with developing these new technologies, it took steps to mitigate the immediate impact by introducing a CO2 Offset scheme from the start of the 2007 model-year in the autumn.

In 2005–2006, Land Rover had to contend with trouble from environmental protesters. This flyer was left on the windscreens of vehicles that offended the sensibilities of activists.

Sports were used as crew vehicles on the 2006 G4 Challenge; this one was crewed by Gabriel Maldonado from Spain and Claribett Vega from the combined Chilean and Costa Rican teams.

The new technologies became public knowledge at the Geneva Show in March 2006, when Land Rover displayed the rather awkwardly named Land_e. This was a Freelandersized skeleton model that presented fuel-saving ideas, and ideas for lightweight, hybrid electric and bio-fuel vehicles. Most of these technologies were a long way in the future, but the Land_e did at least demonstrate that Land Rover had made a start.

The CO2 Offset Programme was then announced to the media on 18 July. Scheduled to run until 2008 and to act as a pilot scheme, this was run in conjunction with Climate Care Ltd. There were two parts to it, one offsetting emissions generated by vehicle assembly at the Solihull and Halewood factories, and the other being a levy charged on top of the showroom price of each vehicle that ‘bought’ 72,400km (45,000 miles) worth of offset. While the vehicles continued to produce undesirable amounts of CO2, the levy was paid directly into aid schemes around the world that made an immediate reduction in locally produced quantities of CO2.

The idea was a little creaky, but it did buy Land Rover time while they developed the promised new technologies. Owner Ford supported the initiative by announcing in July that it planned to spend at least £1 billion developing a range of global environmental technologies in the UK for its Ford, Jaguar, Land Rover and Volvo brands.

The G4 Challenge

After Land Rover had pulled out of the Camel Trophy international adventure challenge event in 1998, the company’s Marketing Department began to make plans for a replacement. This materialized in 2003 as the G4 Challenge – the G4 referred to four geographical zones where stages would take place – and the idea was to focus more on challenges to the individual than on the team spirit of the Camel Trophy. The first event was planned to showcase all four Land Rover product ranges – Defender, Freelander, Discovery and Range Rover – and a fleet of vehicles was specially prepared, using an eye-catching Tangiers Orange colour scheme.

A second G4 Challenge was held in 2006, and as before, featured examples of all Land Rover’s current range of vehicles. This time there were five of them, as the Range Rover Sport had been added to the line-up. The nature of the event also changed slightly, because the 2003 event had been widely criticized as having insufficient focus on the vehicles and too much on the adventure-sports element.

A total of thirty-five 4.4-litre HSE Sports with right-hand drive were prepared for the event, one becoming a publicity vehicle. One vehicle put in a token appearance in Brazil for that leg of the event; thirteen more were used by the press on the Bolivian leg; and the remaining twenty were used by competitors and support staff during the stages of the event held in Thailand. The vehicles were equipped with a number of items from the accessories list, together with a special roofrack (by Monacar), a Warn winch, and a Mantec sump guard and raised air intake. They were all painted in Tangiers Orange, and wore G4 Challenge decals and other identification.

These vehicles were mostly sold off in Britain after the event was over. Some have since been reregistered, and some have allegedly even been repainted for buyers who did not want the Tangiers Orange paint. However, genuine survivors can be recognized by that paint, and by number plates in three sequences, beginning BL05, BN55 and BV55.