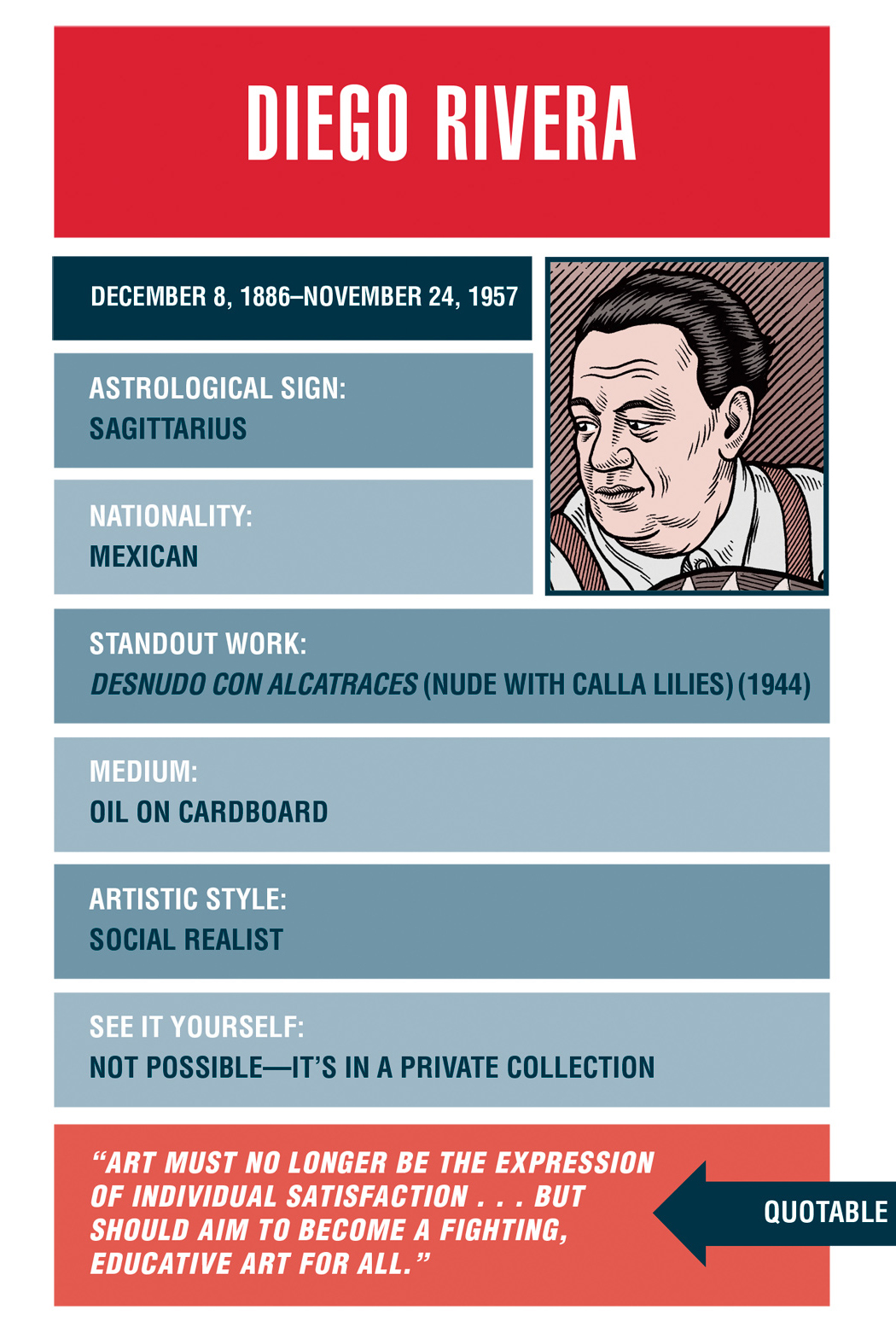

Diego Rivera invented the most fabulous stories about his life. He claimed to have fought in the hills with revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, plotted the assassination of a Mexican president, and even engaged in cannibalism. It’s hard to understand why he felt compelled to invent these tales because, truth is, his life didn’t need embellishment. Born into a downtrodden country suffering political upheavals, he became one of the most remarkable artists of the twentieth century, one who brought unprecedented recognition to indigenous peoples and helped invent a national myth for Mexico. Along the way, he became the close friend of such varied personalities as Pablo Picasso and Leon Trotsky and married (twice) one of the century’s most extraordinary artists, Frida Kahlo.

Cannibalism? Who needs it?

The first myth about Rivera that must be dispelled is his name. He was baptized Diego María Rivera and not, as he later claimed, Diego María de la Concepcíon Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez. He later tacked on a new name for each biographer—after all, he had to keep up with Pablo Picasso.

The story of his birth might or might not have been myth: He claimed he was pronounced dead by the midwife, who deposited him in a bucket of dung, but then his grandmother revived him by killing several pigeons and wrapping him in their warm entrails. Maybe. What is certain is that he was the first born of twins to a middle-class family; his twin brother died very young.

Rivera grew up in a Mexico under the control of Porfirio Díaz, whose dictatorship lasted more than thirty years. Rivera, who had showed early talent in drawing, benefited from the state sponsorship of the arts during the Porfiriato but also witnessed the oppression of the working classes, particularly indigenous populations. Nevertheless, Rivera did not, as he later claimed, march alongside striking mill workers in rural Mexico, nor did he join a band of medical students experimenting with the health benefits of cannibalism. Instead, he attended the state art academy, competed in government competitions, and eventually won a scholarship to study in Europe.

Rivera left for Spain in 1907 and two years later moved on to Paris, where he took up with a young Russian artist named Angelina Beloff, who became his common-law wife. He also became pals with artists like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Amedeo Modigliani. (Rivera famously said, “I’ve never believed in God, but I believe in Picasso.”) His personal life was complicated by a love affair with Marevna Vorobev, whom he pursued while Beloff was in the hospital giving birth to their son, also named Diego. (The baby died at the age of fourteen months.)

Meanwhile, back home, the Mexican Revolution broke out. Glorious words about freedom were bandied about, although the resulting social conditions resembled anarchy more than liberty. Rivera saw the conflict through the lens of Beloff’s Marxist ideology and soon became a Communist. This wasn’t the only change in his life. Rivera had adopted Cubism in 1911, but by the end of the decade, quarrels with other Cubists had soured him on the movement. One day he was struck by the sight of fruits and vegetables outside a Paris shop and exclaimed to Beloff, “Look at those marvels, and we make such trivia!” He began experimenting in the style of Paul Cézanne. The move away from Cubism was completed in 1920 when he met the critic Elie Faure, who proposed that artists should contribute to the advancement of society by painting large-scale works of socialist propaganda. Infused with revolutionary fervor, Rivera decided to return to his homeland and begin painting for the people, setting off in 1921 and leaving behind Beloff, Vorobev, and their daughter Marika.

Mexican officials were as eager to promote public art as Rivera was to paint it, envisioning a series of large-scale murals for public buildings. The artist set to work, although at first he struggled with the demands of fresco painting, and the results were a bit spotty: At one point, he announced he had rediscovered the secrets of the Aztecs, touting a paint base made with nopal, the fermented juice of cactus leaves. Not only was this “discovery” pure fantasy, but the nopal also made a terrible paint binder, eventually decomposing and leaving blotchy stains on the wall.

To look at Rivera’s murals, you would never know he had once been a Cubist. Inspired by pre-Columbian sculptures as well as neoclassical European art, Rivera created simplified figures of bright colors and strong lines. His early murals, often populated by scenes of invading Spaniards, focused on past brutalities. Over time, he created works in which a positive future is built on the precolonial past. In The History of Medicine in Mexico, the right side of the mural shows ancient medical practices under the Aztecs—a midwife helping a woman give birth, for example—while the left shows a modern hospital, complete with masked doctors and enormous scanning equipment undertaking the same tasks.

Rivera jumped into leftist politics, co-founding a revolutionary union and joining the Mexican Communist Party. He even made a short trip to Moscow to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution. In 1929, however, Rivera was expelled from the party for continuing to accept commissions from the bourgeois government. He protested, saying that his paintings depicted the class struggle, but the Mexican party organization had no room in its ranks for the undisciplined, outrageous artist.

And outrageous he certainly was. As he started on a mural for the National Palace, he was having simultaneous affairs with a U.S. art student and Frida Kahlo, a young Mexican artist. (All this after a short-lived marriage with Guadalupe Marin and several other flings.) Kahlo shared his passionate belief in Communism and a devotion to art, and their relationship soon intensified. Casting off his other lovers (temporarily, at least), he married her in August 1929. Kahlo was twenty-two and Rivera forty-three.

By the 1930s, mural work in Mexico dried up as the international depression wrecked the Mexican economy. The United States was also devastated but still had a core of wealthy art lovers who could commission big projects, and for several years Rivera found most of his work north of the border. After working for the Pacific Stock Exchange, he painted a mural for the lobby of the Detroit Institute of the Arts, depicting the manufacturing process at a Ford auto factory. (The irony of a dedicated Communist painting a stock exchange and an assembly line seems to have been lost on Rivera.)

A FABULIST OF EPIC PROPORTIONS, DIEGO RIVERA CLAIMED TO HAVE SMUGGLED A BOMB IN HIS SOMBRERO IN AN ATTEMPT TO ASSASSINATE MEXICAN PRESIDENT PORFIRIO DIAZ.

Rivera then headed to New York to decorate the lobby of the RCA Building in Rockefeller Center. He went to work on a fresco that showed two possible futures: one a capitalist hell and the other a Communist heaven. That would have been bad enough, but then he added a portrait of Lenin to his masterpiece. Panic erupted among Manhattan’s dedicated capitalists. Nelson Rockefeller insisted that the portrait of Lenin be painted over, but the artist refused, offering only to add a portrait of Abraham Lincoln to the mix. The developer handed Rivera a check and escorted him from the building. A few weeks later, in the middle of the night, workmen destroyed the fresco. Rivera later got his revenge: Reworking the mural in Mexico, he included a portrait of Rockefeller holding a martini glass, the ultimate decadent capitalist.

Meanwhile, on the marriage front, Rivera seemed incapable of remaining faithful. His attractiveness to women is hard to understand—by the 1930s, he weighed nearly three hundred pounds and disliked bathing. Kahlo walked out on him in 1935 but returned after both agreed that theirs would be an “open” marriage. The situation was too precarious to last, and in 1939 they divorced, only to be brought back together by one of the figures who had driven them apart, the exiled Bolshevik Leon Trotsky, with whom Kahlo had had an affair. After Trotsky’s assassination, Kahlo was roughly questioned by the police. She fled to San Francisco, where Rivera was working. Despite the fact that Rivera was shacked up with one woman and sleeping with another, the two remarried in late 1940.

World War II saw the decline of mural commissions, so Rivera devoted himself increasingly to portraits and oil paintings. The most famous of these, Desnudo con Alcatraces (Nude with Calla Lilies) is typical of the period: It shows a woman with her back to the viewer, kneeling as she embraces a basket overflowing with enormous white lilies.

After the war, Rivera grew increasingly active in the peace movement, with Kahlo participating as best she could as her health steadily declined; after years of suffering, she died in 1954. Rivera stage-managed her funeral into a Communist demonstration, a sign of loyalty that finally persuaded the Mexican Communist Party to readmit him as a member.

The last years of Rivera’s life found him as irrepressible as ever. In 1955 he married his dealer Emma Hurtado, although he soon started an affair with a prominent collector. The philandering finally ceased when he died in 1957. Despite his wishes, his ashes were not mingled with Kahlo’s and buried in the mock-Aztec temple he had built for himself. Instead, he was laid to rest in the National Rotunda of Illustrious Men in Mexico City.

Diego Rivera believed art could change the world. He didn’t succeed in the way he intended, nor did his paintings usher in a Communist paradise. But Rivera did offer to the Mexican people a vision of themselves as heroes, not victims of bloody colonialism and political repression. The myth-maker Rivera gave his country something it desperately needed: an uplifting story of national identity.

After studying the life of Diego Rivera, one must conclude that his capacity for invention was matched only by the gullibility of his audiences. In 1910, he briefly visited his home country to hold an exhibition in Mexico City. All well and good except that, according to Rivera, he had an ulterior motive: to assassinate President Porfirio Díaz with a bomb that he smuggled into the country in his sombrero. He was forced to abandon his plans, he claimed, only when the president’s wife, rather than the president, attended the opening.

Rivera also claimed he spent six months fighting alongside Emiliano Zapata in the south of Mexico, becoming an explosives expert who could blow up trains without harming passengers. Rivera recounted that he had been dragged forcibly from Zapata’s side by a government official who warned him he was about to be sent to the firing squad. The adventures of the voyage concluded with Rivera rescuing his ship from foundering in an Atlantic storm. In fact, Rivera sailed home on calm seas well before Zapata’s revolt. And instead of throwing bombs at the president, he went to great trouble to ensure the government would continue to pay his scholarship.

After the first flush of excitement over Cubism, artists quickly found themselves split over the “correct” Cubist approach. Synthetic Cubists quarreled with Analytic Cubists, collage-creating Cubists fought with paint-only Cubists, and Rivera developed theories about the fourth dimension that, frankly, make no sense whatsoever. The whole thing came to a head at a dinner party hosted by the art dealer Léonce Rosenberg during which the critic Pierre Reverdy charged that Rivera was basing his art on the discoveries of others. Rivera slapped Reverdy in the face. China and glassware shattered as punches flew. Friends managed to separate the two, although on his way out Reverdy hurled the foulest epithet he could find: “Mexican!”

It didn’t stop there. Reverdy published an article in which he labeled Rivera a “savage Indian,” a “monkey,” and “human only in appearance.” The hubbub was widely reported in Paris newspapers as l’affaire Rivera, although you’d think that in 1917 the French had more important things to worry about. The whole matter gave Rivera a distaste for Cubist theorizing, and within a few years he gave up Cubism altogether.

In the late 1940s, Rivera was charged with opening fire on a truck driver outside his Mexico City house. He protested having fired the shots because he thought the driver was going to knock him down. “Who has not fired a shot in the air to celebrate the New Year?” he asked the judge. “Who has not fired a shot during thirty or more years for the sheer joy of it, even without the blessing of constitutional law? Who has not fired a shot just to get a waiter’s attention?”

Rivera kept kahlo well informed of his love affairs, particularly after their second marriage, and she made no secret of her dislike for her rivals. Once she groused that one of her husband’s favorites had “huge, ugly breasts.” Rivera protested that the woman’s breasts weren’t that big, but Kahlo snapped, “That’S because you always see them when she’s lying down.”

In the late 1940s, Diego Rivera decided to build himself a house—but not just any house. He wanted a temple dedicated to his glory. He called the structure Anahuacalli and based it on the design of Aztec temples, which were more often associated with human sacrifice than with comfy residences.

Constructed primarily of black volcanic stone carved into fantastical shapes, the building is entered by passing through enormous stone gateways and then crossing a moat, which lead to a huge courtyard surrounding a massive stone table. Inside the structure are dimly lit, winding corridors that lead to cramped rooms filled with Rivera’s collection of Pre-Columbian art. At the center of the pyramid on the lowest level is a small room containing a pool of water. The space is reminiscent of the “offering chamber” in which Aztec priests would leave the bones of their victims. Rivera intended the chamber to contain the remains of himself and Kahlo.

Rivera never lived in the house; he died before construction was complete. It was opened to the public in 1964 and today serves as the Diego Rivera Museum.