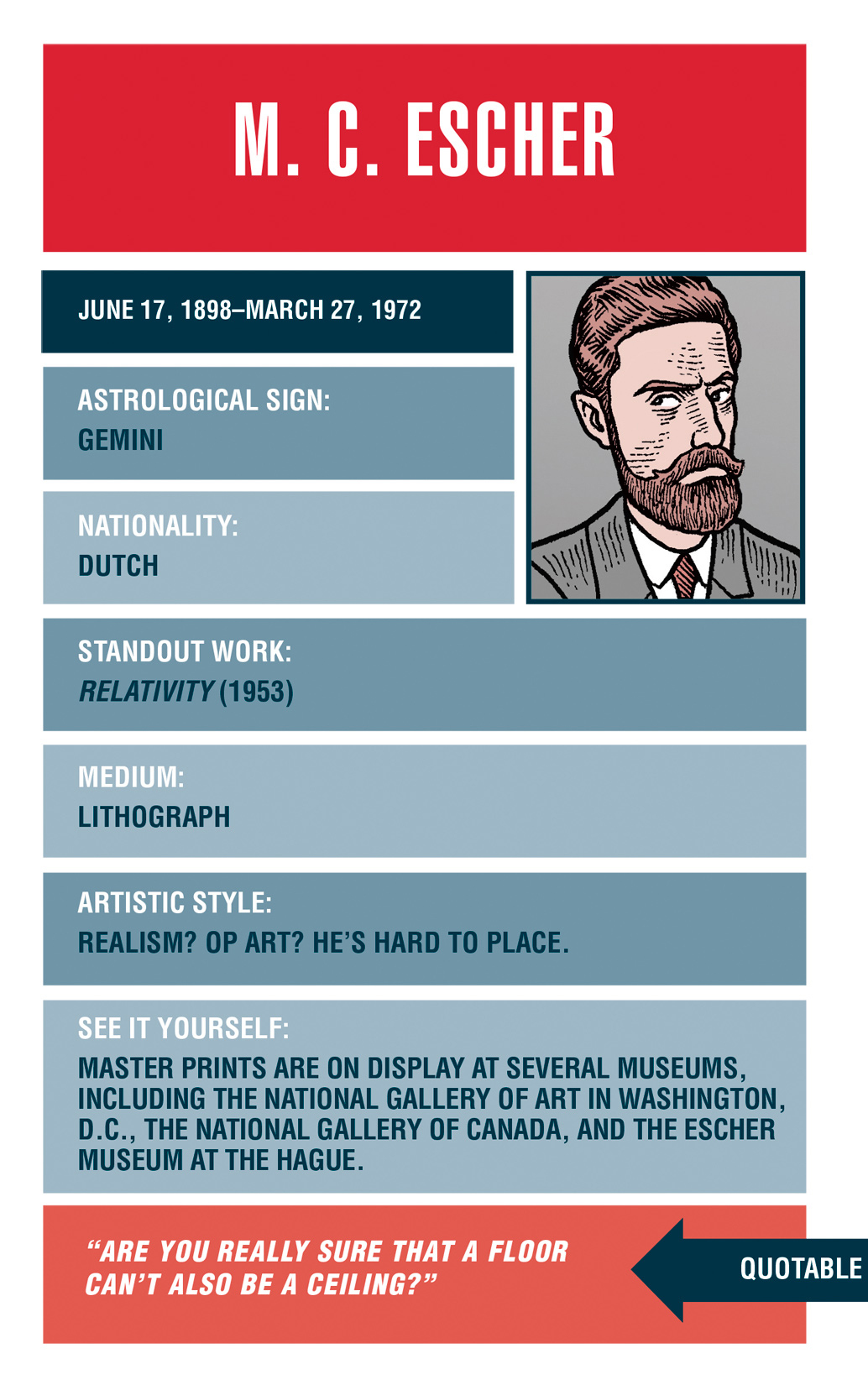

It had been a long while since the days when Leonardo da Vinci spent so much time exploring geometry problems that he couldn’t concentrate on his paintings. Few artists had cared much about math, except to compare their commissions to their bar tab. And then along came M. C. Escher.

Escher didn’t start out as the mathematician’s artist—he was a printmaker, fascinated with depictions of the Italian countryside—but a visit to a Moorish palace and a glimpse at a fascinating world of interlocking patterns revealed that math could be used to create art. The results were bizarre, fascinating works that to this day are more popular among the lab-coat set than museum curators.

Maurits Cornelis Escher was born into a prosperous Dutch family in Leeuwarden, the youngest son of a successful civil engineer. The family moved to Arnhem when he was five. At school he did poorly in every class but art, failing math and geometry. In 1919 Escher enrolled at the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts, where his father hoped he would study architecture. He quickly switched his focus to printmaking, thus the world has been robbed of Escher’s architecture everywhere except on paper. (One can’t help but wonder where the stairs would have started and ended.) He finished school in 1922 and set off on a trip to Italy. So entranced was the young artist by the Italian hills that he decided to settle there. He produced print after print of tiny Italian villages and craggy hillsides, without particular commercial success. He was more successful in love, falling for a young Swiss woman named Jetta Umiker; they married in 1924 and had three sons. The family’s happy life in Rome was disrupted by the rise of fascism, prompting a move to Switzerland, where they lived for two years before relocating again to a suburb of Brussels, Belgium.

Escher seemed to have reached the artistic limits of his landscapes when a summer visit to Spain provided a new source of inspiration. In 1936 he boarded an ocean freighter and sailed around the Spanish coast, a trip he got for free in exchange for making prints of the company’s ships and ports of call. Along the way he paused to draw, with one rest stop bringing him to the Moorish palace of the Alhambra in Granada.

Muslim art is, by religious mandate, nonrepresentational, and so over the centuries Islamic artists have developed intricate abstract forms. The Alhambra includes several magnificent tessellating tile works in which each plane is divided into interlocking geometric shapes. Escher was fascinated by the tessellations and spent hours sketching the tiles. Upon returning home, he struggled for weeks to create tessellations as beautiful and complex as those he had seen in Granada, but the process was a time-consuming matter of trial and error. Escher confided his difficulties to his brother Berend, a professor of geology at Leiden University, who immediately recognized that Escher’s tessellations were mathematically related to concepts in crystallography, the study of how crystals form. Berend sent his brother a list of articles on crystallography and plane symmetry, the study of two-dimensional symmetry and repeating patterns. Escher didn’t quite understand all the math (he’d failed algebra, remember?), but he intuitively understood the concepts described within.

Soon he was off, applying the new mathematical concepts to his artwork. Once he mastered tessellations, he started experimenting with subtle variations: A tessellation of fish and birds became a gradual metamorphosis between one creature and the other. Why stop with two-dimensional surfaces? Escher tried tessellations on a sphere, carving interlocking swimming fish onto a wooden beech ball. Then he depicted three-dimensional tessellations on a flat surface by creating elaborate graphs.

The outbreak of World War II interrupted these enjoyable artistic/mathematic musings and sent the family scrambling from Brussels to Baarn, in the Netherlands. Food was short, and the Nazi presence frightening. Escher’s Jewish art teacher from college, Samuel de Mesquita, was seized and killed. Escher responded by turning inward. Rather than depict the real world, he created an imaginary one. His imagination was a far more logical place than the fantasy land of the Surrealists, although it was just as odd. Take Relativity (from 1953 but based on work begun during the war years): Figures in a building are shown walking up and down stairs and along corridors. Nothing seems unusual, until you realize that the image is impossible: Every surface is at once a floor, a ceiling, and a wall. On one staircase, people walk on both the top and the bottom of the stairs.

Escher had again happened upon a field usually reserved for scientists: optical illusions. By providing conflicting clues, his art confuses the brain, which tries to make sense of what it sees but fails. Waterfall, of 1961, features a precisely drawn, but physically impossible, scene of a waterfall feeding itself. We want to believe that the series of zigzagging channels is ascending—one corner is clearly positioned above another—but ignore the corners and what you’re left with is a flat channel that can’t possibly carry water up. Look at the image long enough and your brain starts to hurt.

MICK JAGGER IMPLORED M. C. ESCHER TO DESIGN THE COVER OF THE NEXT ROLLING STONES ALBUM, BUT THE OLD-WORLD GENTLEMAN-ARTIST WAS TURNED OFF BY THE ROCKER’S PRESUMPTION IN ADDRESSING HIM AS “MAURITS.”

For most of his life, Escher worked without recognition, a fact that certainly had a lot to do with the division between graphic arts, such as printmaking, and fine arts, such as oil painting. Plus there’s the simple fact that Escher’s work was downright odd.

Perhaps appropriately, mathematicians were the first to discover the artist. In 1954, an exhibition of his work was held in Amsterdam to coincide with the International Congress of Mathematicians. The math people recognized immediately what Escher was trying to do—and they loved it. Scientists started inviting him to lecture at colleges and universities, and by the late 1950s he was struggling to find time to create new designs amid his busy touring schedule. Ill health started to trouble him in the 1960s, and he made his last lecture trip to the United States in 1964. In 1968, his wife of forty years up and left for Switzerland; apparently she had never liked living in Baarn. (Their son said of the split, “She was tired of playing second fiddle.”) In 1970, Escher moved to a home for retired artists, where he died in March 1972.

Assessing Escher’s influence is difficult. Even today, you’re more likely to see an Escher print on the wall of a physics professor’s office than in an art gallery. (The Museum of Modern Art in New York has none of his work in its collection.) Yet Escher’s work took root in popular culture and pops up everywhere from episodes of The Simpsons to the Tomb Raider movies. There’s a definite geek element to his fan base—mathematicians still write articles based on his work—so maybe it’s not surprising to find Escher references in such eccentric places as video games, comic books, and Japanese manga.

MATH AND THE MODERN ARTIST

The conversation about math wasn’t one way, for Escher also contributed to mathematical research with his exploration of tessellation and symmetry. In 1958 he published a paper titled “Regular Division of the Plane,” in which he detailed his mathematical approach to artwork. It summarized how he categorized combinations of shape, color, and symmetry and set out pioneering methods that were later adopted by crystallographers.

In the 1960s, as Escher’s popularity was growing, Mick Jagger decided it would be a great idea to have the artist design the cover of the next Rolling Stones album. The rock-and-roller wrote a letter that began, “Dear Maurits … ” Escher, a man of an earlier, more formal time, replied, “Don’t call me Maurits.”

Escher really hit the big time in 2006 when he got a mention in the Weird Al Yankovic hit “White & Nerdy,” from Straight Outta Lynwood. A parody of the hip-hop single “Ridin’ ” by Chamillionaire and Krayzie Bone, the song features Weird Al reveling in his nerdiness by collecting comic books, playing Dungeons & Dragons, and editing Wikipedia entries. In one line, he claims, with sincerity that many a geek could appreciate, “M.C. Escher, that’s my favorite M.C.”

THROW-AWAY ART

Many modern artists dismissed the work of M. C. Escher, who happily returned the favor. He deemed the emotional, spontaneous art being created during the mid-twentieth century as sloppy and incomprehensible and complained that his contemporaries could never explain why they painted what they did. When several of Escher’s prints were exhibited alongside the works of modern Dutch artists, he scribbled on a catalog that he sent to a friend, “Whatever do you make of such a sick effort as this? Scandalous! Just throw it away when you have looked at it.”

Curiously, one of the few artists that Escher admired was Salvador Dalí. Despite their opposite personalities, Escher approved of Dalí’s skill in drawing, stating: “You can tell by looking at his work that he is quite an able man.”