3

River and Catchment

The wildwood

The time is 5000 BC. Britain is an island and the sea forms a great estuary deep into Broadland. Soaring above the valleys, the sparrowhawks eye a near unbroken cover of forest. Trees, mostly lime and hazel with oak and elm, or alder and sallow, stretch from the uplands of the interior until the sea is almost reached. Only there does the forest stop and the open mud flats and salt marshes of the estuary lead to the offshore waters. Inland they merge with a narrow band of reedswamps, where the water at high tide is too salty for alder and willow, but too fresh for salt marsh. The upper stretches of the rivers, deep in the interior, are hidden by overhanging trees. Only when directly overhead can the birds see the open water of the rivers except where these widen in their lowest courses. At an angle they too disappear into a green uniformity as far as the eye can see.

At low tide, in the coastal shallows, there still remained the blackened remnants of submerged forest that had covered the whole basin of the North Sea only centuries earlier and which had linked the future island of Britain to mainland Eurasia. Through this now submerged forest, along the valleys of rivers that had formed the tributaries of the Thames then the Rhine, the animals of the forest had returned as the climate warmed. Through the rivers themselves had come the fish and some of the invertebrates. Through the air had come birds and insects, seeds and spores to recolonise the ice-devastated lands.

After some centuries of establishment (Fig. 3.1) the forest had reached a form of dynamic stability. There were still many changes of species as minor turns in the weather, and the longer-term temperature trends, favoured some over others and then reversed the change. Old trees fell, leaving small clearings that became grassy and were perhaps kept that way by the grazing of moose, red deer and wizent. Sometimes the crows and ravens flocked over a clearing where wolves had killed or where the smell of a brown bear dead of old age had attracted them to the carcass. Eagles hunted fawns and calves of the native deer and wild cattle and occasionally a group of men passed through, themselves part of the upper reaches of the forest food web.

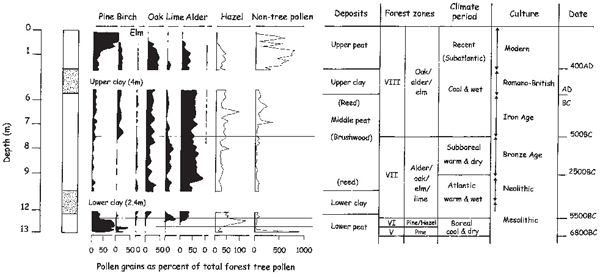

Fig. 3.1 The history of Broadland encapsulated in the pollen from a core through the 13 metres of deposits laid down between Ranworth Broad and the River Bure. Counting of pollen grains from samples of peat is a well-established method of assessing vegetation changes. Care is needed in interpretation because different trees produce greatly different amounts of pollen. Lime, for example, was a much more abundant tree than it seems from the core. Conventionally numbers are expressed as a percentage of the total forest tree pollen (hazel is not included in this group as it is a shrub). Time zones, numbered by Roman numerals, and later given names, are recognisable from the pattern of species predominance and have been dated by radiocarbon dating and linked with major archaeological periods. Marine clays do not preserve pollen well because the tides tend to wash the grains out to sea before they can be deposited and because grains that do become incorporated are often abraded in the sharp sediments. The tree pollen comes from quite a wide area, so reflects events within a region, not specifically at the immediate locality of the core. The recent rise in pine in this core probably reflects planting of pine forests in southern Norfolk in the twentiety century. The rise in non-forest (herb) pollen from Zone VIII onwards reflects the rise in agriculture, whilst that in Zone V probably indicates a more open woodland in cool, dry conditions. Pollen data from a core analysed by J.R. Jennings and originally published in Ellis (1965).

There was much dead wood. Great tree trunks and branches crisscrossed on the forest floor, creating protected nurseries where grazers found it difficult to move without risking a leg, thus allowing tree seedlings to survive and the forest to continue its cycle of regeneration. The soils were no longer new. At first, raw with the fresh rock flour ground from distant lands by the ice, they had been rich in unweathered minerals. These, under the action of air and water, had at first yielded large supplies of plant nutrients – calcium, magnesium, phosphate and potassium. Soil bacteria capable of transforming the nitrogen gas of the air into usable nitrogen compounds had moved in. Rain had provided chloride, sulphate and sodium from the supply of sea spray swept into it from the breaking white horses during storms. Those airborne seeds flexible enough to cope with the rigorous microclimate of a bare land had multiplied, adding organic matter to the soil when they died.

But now things had settled. The first flush of soil nutrients had long passed down to the sea and was lost in the vast volume of the ocean and the great reaches of its bed sediments. The remaining nutrients were tightly held in the biomass of the trees, to be released on rotting of leaves and wood, but quickly recaptured by young roots and their associated mycorrhizal fungi. Some plant nutrients, nitrogen, for example, had always been scarce and conserved. Now almost everything was kept in a nearly complete cycle with only a little lost to the rivers and streams, more or less at the same rate as it was brought in from the atmosphere or by weathering deep in the soil profile. The streams dissolved very little in total amount, but contained a huge variety of different substances.

The chemistry of water

Water chemistry is an intensely interesting subject. It is not just water that flows out of the catchments and down the rivers, but a mixture of several thousand dissolved substances and perhaps as many in the form of suspended particles. Most of these substances are organic carbon compounds, the results of death and decay, and leaching of humus in the catchment soils. Some are rather resistant to further decay and may colour the water yellow or brown or become deposited in the river sediments. Others are very reactive and last for only a very short time before bacteria coating the sediments or stones of the river break them down further, eventually to carbon dioxide.

Then there are many inorganic substances, again some dissolved, others appearing as mineral particles eroded from the soils and contributing eventually to the river sediments. The dissolved inorganic substances tell us a great deal about the catchment and they largely determine the biological potential of the water. They can be divided into the major ions, minor ions and key nutrient ions. Major ions are major because they occur in the greatest concentrations, though these amount at most to only a few tens of milligrams per litre (parts per million) in fresh waters. They are ions because they exist in an electrically charged form, compared with the electrically neutral free-existing element. The minor ions occur at microgram per litre (parts per billion) or even lower concentrations, and the key nutrients at various concentration levels, but spanning the range up to only a few milligrams per litre. Unlike the former two groups, they are non-conservative – their concentrations vary considerably over short periods as they are biologically very reactive. There are also the gases dissolved from the air.

The major ions include sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, hydrogen, chloride, sulphate and bicarbonate. The minor ions include many of the trace elements such as copper, zinc, boron, iron and manganese – indeed if sufficiently sophisticated analytical equipment is available, it is probable that at least a little of almost every stable element could be detected in all natural waters. The key nutrients include compounds of phosphorus, phosphates and nitrogen, particularly ammonium and nitrate. Silicon may also be a key nutrient because one particular important group of algae, the diatoms, requires silicates for the formation of its cell walls. The important gases are nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide.

In some waters the major ions are comparatively scarce because the catchments from which these waters come are floored by hard and resistant rocks, which weather slowly, and contribute little to the rainwater seeping through and over their thin soils. Such waters might have much lower than ten milligrams per litre of each of the metal ions, such as potassium and calcium, and the most abundant will be hydrogen ion. The pH values will thus be low, perhaps 5 or 6. pH is a measure of the amount of hydrogen ion expressed as a minus logarithm – the higher the hydrogen ion concentration, the lower is the pH and the more acid is the water. Calcium, bicarbonate and potassium, which come mainly from rock weathering, will be very scarce, and sodium and magnesium, chloride and sulphate, ultimately derived from the sea spray caught up in rain, the more abundant. Such waters, often called ‘soft’, are found in the uplands such as those of the English Lake District and the Scottish Highlands.

The waters of Broadland are rather different. They are ‘hard’ and come from the chalk and the finely divided minerals brought from under the glaciers as they ground their way over many different rock formations, including many soft sedimentary ones. From the beginning the Broadland waters would have been comparatively rich in major ions, with tens of milligrams of calcium, magnesium and bicarbonate, derived from the chalk. They would have had a higher pH, 7 or 8, because of neutralisation of the acidity by the carbonates, and high levels of sulphate and chloride, still from rain, but concentrated through evaporation of greater proportions of the rainwater in the warmer lowlands.

Although living organisms, be they bacterium, animal or plant, must have all of these elements, they need them in quite small quantities in relation to the supplies, even in soft waters. The concentrations of most substances in the water thus change relatively little in response to biological uptake. When they do change, it is mostly in response to factors such as evaporation and rainfall in the catchment. Heavy rain leads to more surface runoff and lower concentrations because less water percolates through the ground to pick up ions from the soils and rocks. Moderate rainfall leads to higher concentrations and low rainfall to the highest of all. The total load carried in a given time (say kilograms per day), as opposed to the concentration (milligrams per litre), generally increases, however, with the amount of runoff.

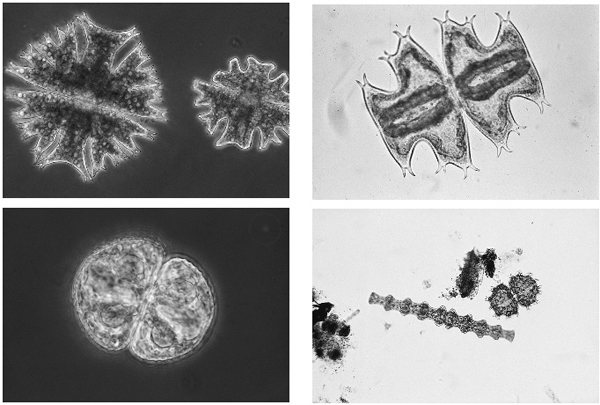

Major ions thus do not determine the productivity or fertility of natural fresh waters, but they may influence the nature of the biological communities (Fig. 3.2). Some groups of freshwater algae, in particular the desmids, a group of green algae, are abundant in soft, acid waters, and scarce in carbonate-rich ones. This is because most of their species cannot use bicarbonate for photosynthesis, but only free carbon dioxide. They are displaced by other algae when bicarbonate is abundant. Snails, and crustaceans such as the freshwater shrimp, are much more common in high calcium waters because of the need for lime for their shells and exoskeletons. Not surprisingly, Broadland waters have few desmids, but many snails and crustaceans.

The trace elements figure only a little in understanding the main features of the productivity of fresh waters. They are important, for organisms cannot manage without them, but, despite their very low concentrations, they are generally abundant in relation to organisms’ meagre needs. Iron and manganese enter into reactions that affect the key nutrients and are important in this respect, but for the moment we can ignore them. What we cannot do is to ignore the key nutrients, for more than anything else dissolved in the water, their availability underlies the entire ecology of fresh waters in general and Broadland in particular. The key is that these nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus, are relatively scarce and also, of course, crucial to life on land. Natural terrestrial communities have evolved mechanisms to retain them and so the natural supply allowed to run off into fresh waters is very low indeed. Often they are called the key limiting nutrients for this reason.

Fig. 3.2 Desmids are green algae that are most common in low bicarbonate waters and hence very few species are found in the open waters of Broadland. Top, two species of Micrasteras, each over 100 micrometres in length. Micrasterias species, Xanthidium (the spiny cell) and Pleurotaenium (the long cell) at the bottom right cannot use bicarbonate and are very rare in Broadland, but Cosmarium (bottom left) can and is common in Broadland ditches.

Phosphorus is very scarce in most natural fresh waters. Living organisms need its compounds to form some of the crucial biochemicals used in the cell for transferring energy and for making DNA, the material of the genes. They do not need much of it – only a fraction of one per cent of their weight, but it is a scarce element relative even to this need and its compounds, largely phosphates, are relatively insoluble in water. They can be tightly held in soils as minerals such as apatite (calcium phosphate) and attached to clays.

Rooted plants can winkle enough of this phosphorus from the soil minerals through the intimate contact of their finer rootlets and often the fungi or myc-orrhiza that are associated with them. They also have the benefit of greater concentrations of the element, often grams per litre or kilogram (parts per thousand), even in the poorest soils. This advantage can apply also to the larger submerged plants, called aquatic macrophytes, rooted in mud that has been washed in from the land to freshwater habitats. The microscopic algae suspended in the water as plankton in lakes or growing as films over the rocks on the bottom of rivers do not have this advantage. For them the problem is of obtaining enough phosphorus from concentrations in the water that are usually only a few micrograms per litre, up to a million times lower than in soil.

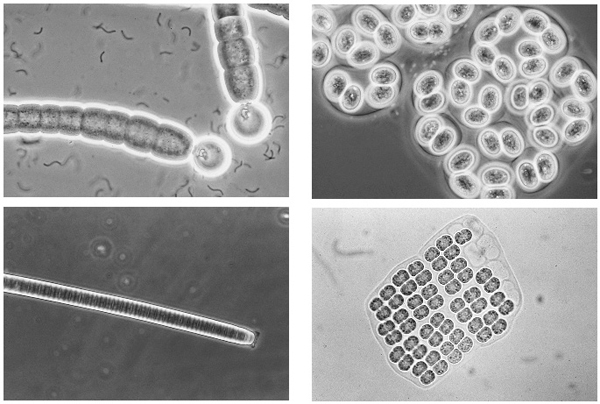

Nitrogen is the second element that in short supply will limit aquatic growth. Supplies of nitrogen are greater than those of phosphorus, but so are needs. Nitrogen is needed in large quantities for the production of proteins by cells and about ten times as much as of phosphorus is required. There is plenty of nitrogen on Earth, but most of it is present as a gas in the atmosphere which, even when dissolved in water, is not readily available to living organisms. It must first be converted to amino compounds, a process called fixation, in which the nitrogen is combined with hydrogen. Apart from some chemical conversion by high-energy lightning sparks, which are minor contributors, this can be done naturally only by certain bacteria in soils and waters or associated with the roots of some plants, such as the legumes. Most of these bacteria, despite their immense importance as the main gateways for nitrogen to enter the biosphere, are nondescript organisms, but nitrogen fixers also include some of the blue-green algae or cyanophytes (Fig. 3.3), which are more spectacular to look at, but have a bacterial cell structure.

When nitrogen fixers die, or are eaten, their fixed nitrogen enters other parts of the food webs and is released, after decay, into the interstitial water of the soils as ammonium or nitrate, and washed out into the rivers. In contrast to phosphates, nitrates and ammonium compounds are very soluble and readily leached out. There is a problem, though, in terms of their later availability. Ammonium is readily converted by other bacteria, which derive energy from the reaction, to nitrate. Nitrate can then be used by yet more bacteria as an oxidising agent, under waterlogged conditions, when oxygen is scarce, to release energy from organic matter. This converts the nitrate back to nitrogen. All in all, events contrive therefore, under natural conditions, to keep most of the nitrogen as nitrogen gas and to make an otherwise abundant element relatively unavailable.

The early Broadland waters

As the rainwater fell onto the Broadland catchment in 5000 BC, it went through a series of processes that culminated in a small proportion of it – that quarter or so which was not evaporated or transpired by the vegetation – pouring out into the streams as a much more complex chemical solution than had fallen on the forest. It was a dilute solution with perhaps a couple of hundred milligrams of dissolved solids in every litre. Half of these were organic, the humic compounds left over from the decomposition of wood and cellulose. About half was a complex of major ions, dominated by calcium and bicarbonate, at neutral or slightly alkaline pH (Table 3.1). Tiny fractions were made up of a few micrograms of phosphorus in the form of phosphates and a milligram or less in every litre of nitrogen as nitrate. Ammonium was vanishingly scarce; it is so reactive that bacteria quickly convert it, or plants take it up. A huge variety of other organic compounds and trace metals would have contributed a minuscule proportion of the total.

Fig. 3.3 Blue-green algae sometimes dominate the plankton communities of the Broads. Some can fix nitrogen, most cannot. Those that can usually have large, translucent cells (heterocysts) in which the particular conditions necessary for fixation (low oxygen concentrations) are maintained (e.g.Gleotrichia top left). The others are not fixers. Chroococcus (top right) occurs attached to surfaces, Oscillatoria (bottom left) may grow on sediments or be suspended in the water, as may Merismopaedia (bottom right).

For most of the year this solution would have seeped gently from the forest floor as a very pale yellow fluid into channels only centimetres across, but which widened and joined to form streams metres wide and eventually rivers tens of metres from bank to bank. The Broadland rivers were never very large by world standards, not even falling into the upper echelons of a league of British rivers. Even the largest of these, the Severn, is a trickle compared with the Rhine, the Volga, Nile or Amazon.

But following heavy rain, a thunder shower in summer or steady winter downpours when the soils were saturated, the water draining the Broadland catchment would pick up debris from the forest floor. Where a tree had fallen and soil was temporarily exposed, some would erode; leaf litter would be washed in from the banks, twigs and sometimes, larger branches also. Sometimes banks might be undercut and whole trees collapse into the flow. As the spate passed, the finer particles would settle out behind obstacles such as stranded branches and tree trunks, and dead leaves would pack like piles of paper into crevices among the debris. The flux would leave a highly structured habitat, full of the architecture of woody debris, for the stream community.

Table 3.1 Major ion composition of Broadland rivers, compared with rivers elsewhere, rain and sea water. Values are typical ones – they vary a little with weather and river flow – and are given in milligrams per litre. nd: not determined.

The soaring sparrowhawk looked down on a sheet of forest in which all but the lower reaches of the rivers would have been hidden by the tree canopy. Equally, for animals living in the upper reaches of the rivers, the sky would have been blocked by a dense network of overhanging branches, made nearly opaque by the summer leaves. The stream bottom was naturally a very dark, shaded place. Photosynthetic organisms had a hard time of it. There were, however, some algae on the larger of the flints washed out of the chalk and exotic stones brought in by the ice, which bottomed the main channel and on those few sections where the underlying chalk itself was exposed under water.

In spring, before the canopy leaves developed, a brown film of diatoms would have grown, to be grazed away in weeks by snails and mayfly nymphs and replaced by tougher green algae more entrenched in the surface crevices of the stones. Some water mosses and freshwater red algae may have colonised where the light was marginally improved by temporary breaks in the forest cover, but there would have been almost no higher plant growth until the widening rivers had almost reached the sea. Nonetheless, if the models with which we might compare this ancient ecosystem, in the uncleared hardwood forests of America and mainland Europe, are to be relied upon, there was a vigorous bottom community of invertebrate animals and of fish and other vertebrates.

The animal community of the early Broadland streams

Most of the food for this animal community did not come from green plants or algae in the stream, but from the organic silt, dead leaves and woody debris washed and falling into the streams. Much of this material was nutritionally poor. It was rich in carbohydrates such as cellulose and lignin, but these are difficult to digest for most animals, and low in nitrogen, for the trees move scarce nutrients back into their trunks before the husks of the leaves are allowed to abscise and fall to the ground.

But present in the streams was a specialist community of fungi, a group called the Hyphomycetes. These fungi are distributed by spores shaped like grapnels, anchors or hooks, which can catch onto organic debris even in swift flows, and then germinate, pushing their fine filaments, called hyphae, over the surface and deep into the dead leaves and wood. Such fungi absorb nitrate from the water and, with enzymes strong enough to digest cellulose and lignin, convert them into fungal material. This progressively softens the debris and enriches it with fungal protein. It is then far more palatable to invertebrate animals and is seized upon by insect larvae, crustaceans and others who shred it to gain access to the fungi. The leaves become skeletonised as the shredders bite out the softened parts between the harder veins.

The finer organic matter washed into the streams also becomes colonised by bacteria and fungi and a similar process goes on. Oligochaete worms and the larvae of flies burrow into banks of silt, swallowing the material and absorbing the digestible portions, largely the cells of bacteria and hyphae of fungi. The rest they defecate and the faeces become colonised by more microorganisms and eaten again. There are also animals that can filter fine particles from suspension using specially modified limbs, or by spinning nets. They capture material disturbed into suspension by wind, or spates, or watering mammals as they wade. The organic matter that entered from the forest, either as large lumps or fine particles, is progressively converted into carbon dioxide and invertebrate biomass.

We can add little reliable detail to this picture in terms of what particular invertebrate species were present in the pristine Broadland system 7,000 years ago. It has long been disturbed, not least by felling of the forest and human modifications of the water chemistry by farming and settlement. We can be sure it was a rich community, for insects colonise rapidly by air as flying adults and other invertebrates through floods that bring the headwaters of lowland river systems into contact. By 7,000 years ago, when the sea level had risen to around its modern position, there had been several thousand years of contact between the Broadland rivers and the Thames and the Rhine, for colonisation to occur. The headwaters of the River Waveney merge with those of the Ouse, which flows to the Wash, and there could easily have been transfer between them. Even in isolated experimental tanks stocked with water and a food supply, it takes only days for the first animals to arrive and only weeks to build up a community of several dozen species. There is still a considerable movement of insects between mainland Europe and Britain.

The modern community – a hint of the past?

In late 2000, the Environment Agency of the British Government announced that the state of English rivers was better than at any time since records began. Alas, such statements are of limited significance, for the records are only a couple of decades old and, even with controls on recent modern pollution, the rivers are still far from the condition they were likely to have had some thousands of years ago. Upstream river communities, unlike those of floodplains and lakes where sediments are deposited, and with them some record of the past, leave no trace. They erode their beds and obliterate their history. All we can have for the Broadland rivers is the present and our judgement on its meaning. The channels are now much more open than they were. The source of the tree litter is gone and the greater light intensity encourages the growth of water plants, water-crowfoot, Canadian pondweed, watercress, brooklime, water moss, starwort, milfoil, bur-reed and water-parsnip. Much more nitrogen and phosphorus wash in from the land and encourage the growth of these and particularly that of filamentous algae such as the blanket weed. There is much more soil, eroded from the land, in suspension. Meanders have been straightened and former wet meadows at the bank side drained.

The animal communities of the river beds are thus likely to be poorer in species diversity, for nutrient enrichment encourages the competitive species that oust the more specialised. Alternatively they could be more diverse, for some litter still enters from trees along the banks and there are now the new habitats provided by the plants. They are likely to be poorer in the species that process litter, but richer in those that feed on fresh green matter, be it plants, or the algae that grows on them or on the larger stones and shingle. Current speeds will also have changed, not only because of natural fluctuations in rainfall, but because the runoff from agricultural land may be very different from that under forest. Agricultural land is often irrigated with water taken directly from the river or from the ground water, which also formerly fed it. Much of this water evaporates from the land and never returns to the river.

The invertebrate communities of the river beds (Fig. 3.4) are useful indicators of the quality of water and are widely used together with chemical analyses, to monitor it. In the past three decades, the former Freshwater Biological Association, now merged into the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, a British Government research institute, has built up a high quality archive of data from over 600 reference sites, where the stream quality is believed not to be affected by gross organic or industrial pollution. Several sites in the upper reaches of the Yare, Wensum, Bure and Waveney were included and give a picture of the current community. The rivers were sampled by a standard and very simple technique, that of ‘kick sampling’, though what actually happens is often less active than the name suggests. The sampler stands upstream of a net held on a pole and disturbs the bottom with his or her feet, dislodging the animals into the net, and moving among the sub-habitats (gravel, silt, plants) of the location during a time of three minutes. This is done three times a year, in spring, summer and autumn, and a list of species compiled. The net is of fairly coarse mesh (half a millimetre) and designed to catch the macroinvertebrates, not the smaller animals such as Protozoa, nematodes, rotifers and cope-pods. These are likely to be at least as diverse as the macroinvertebrates, but their identification is much more difficult, which makes them less useful for practicable water quality surveys.

A total of 637 species, or species groups where further identification is not feasible (for example, with chironomid fly larvae) has been recorded, with about 200 of them in the Broadland rivers, though any given site will have between 50 and 90. The main groups of animals to be found (Table 3.2) include: flatworms, or triclads, each a few millimetres long and feeding on the damaged bodies or carcasses of bigger animals by sucking out the body fluids; the snails or gastropods and two-shelled bivalves among the molluscs; the oligochaetes, a group related to the earthworms, but much smaller in fresh waters; leeches (which feed mostly on invertebrates and are not usually bloodsucking); and various crustaceans, including the pond shrimp, Gammarus, perhaps the most ubiquitous of all the species, water hog-louse, Asellus, and crayfish. The snails feed by scraping the algae from stones or firm sediment surfaces, the bivalves by sifting sediments for bacteria and organic matter and the crustaceans on filamentous algae or by shredding leaf litter.

Fig. 3.4 Invertebrates tell much of the conditions in river water. This collection includes (top left to right) an oligochaete worm and a chironomid larva, which ingest sediment, and Hydra, which attaches itself to plants and captures smaller animals, only a fraction of a millimetre in size. In the middle are a shredder, Asellus, which feeds on leaf detritus and sometimes algal filaments, and a common snail, Lymnaea pereger, which scrapes algae and bacteria from surfaces. At the bottom are two predators, a water mite, Hydracarina, and a bug, Corixa. Both transfix their prey with sharp projections and suck out the contents.

Table 3.2 General composition of the macroinvertebrate communities (as number of species or species groups in each location) in the upper reaches of the Rivers Wensum, Yare and Bure. Data were obtained by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology as parts of contracts to the Department of the Environment and the Nature Conservancy Council (Wright et al. 1992).

Then there are many insect groups, present as nymphs, juvenile stages that have the typical insect body pattern of head, thorax with six legs and abdomen, or as larvae, which look very different from the adults, or as all stages including the adult. The mayflies (Ephemeroptera), stoneflies (Plecoptera), dragon-flies and damselflies (Odonata), lacewings and alder flies (Megaloptera and Neuroptera) and the very abundant caddis flies (Trichoptera) fall into the nymphal group, the even more abundant two-winged flies, the Diptera, into that which is represented by larvae, and the beetles (Coleoptera) and bugs (Hemiptera) are present also as adults.

Some of these insect groups, many of the beetles and bugs and the Odonata, for example, are predators on other invertebrates; others, including some Diptera, shred leaf litter and many, particularly the mayflies, stoneflies and caddis flies scrape algae and organic matter from surfaces. Some caddisflies, those lacking the cases characteristic of most of the group, spin nets to catch fine material as do dipterans such as Simulium, the blackflies, whilst other Diptera, including the abundant chironomids, feed on sediment organic matter with the oligochaetes and bivalves.

From the Britain-wide survey it is possible to calculate an average composition for stream communities, that shows Diptera to be the most frequent (28.9 per cent of the total list), then beetles (16.5 per cent), caddis flies (15.6 per cent), oligochaetes (8.1 per cent) and mayflies (5.9 per cent). All other groups constitute less than 5 per cent of the total. Among the upper Broadland rivers there are some interesting deviations from the average picture. Snails are much more frequent than the national average, as are triclads, leeches, crustaceans, bivalves and mayflies, whilst stoneflies, dragonflies, bugs and beetles are much less so. The abundance of snails and bivalves undoubtedly reflects the calcareousness of the waters, whilst stoneflies are generally much more associated with upland sites.

No very unusual species turned up in the Broadland river samples, with the exception of one somewhat rare beetle (Haliplus laminatus). The species found in all or almost all of the samples constitute a very characteristic list from lowland streams and small rivers: Polycelis nigra, Dendrocoelum lacteum (triclads), Valvata piscinalis, Potamopyrgus jenkinsi (gastropods), Sphaerium corneum, Pisidium nitidum, Pisidium subtruncatum (bivalves), Lumbriculus spp., Stylodrilus heringianus, Limnodrilus hoffmeisteri, Psamorycitides barbatus, Aulodrilus pluriseta (oligochaetes), Glossiphonia complanata, Helobdella stagnalis, Erpobdella octoculata (leeches), Asellus aquaticus, Asellus meridianus, Gammarus pulex (crustaceans), Baetis scambus, Baetis vernus, Ephemerella ignita (mayflies), Elmis aenea (beetle), Hydroptila spp., Polycentropus flavomaculatus (caddis flies) and Simulium erythrocephalum, Simulium ornatum, Thienemannia spp., Cricotopus spp., Microtendipes spp., Polypedilum spp., Micropsectra spp., Paratanytarsus spp. (Diptera, with the last six being chironomid species).

Current speed is a major factor in determining the existence of many of these species, and streams usually show a spectrum of speeds dependent on the effects of vegetation, bends and backwaters to complement the greatest speeds of the central channels. Some of the tributaries of the main rivers (for example, the Scarrow Beck and Broome Beck) can show speeds of more than 60 centimetres per second and have shingly bottoms. Parts of the Wensum and Tas have gravels and speeds of at least 30 centimetres per second, whilst sandy, silt and muddy reaches can be found on all the rivers with speeds of 20 centimetres per second or lower. The nature of the bottom is important for what were probably formerly common fish, the sea trout and Atlantic salmon, which found their way up from the sea to spawn in the gravelly and shingly beds of these streams. Salmon are now absent for reasons of over-exploitation at sea as well as silting up of many of the former gravel beds, and the trout are widespread, but as their more resilient non-migratory race, the brown trout. Small, bottom-feeding fish, the three-spined stickleback, stone loach, dace, bullhead (also called miller’s thumb) and minnow are widespread.

Down to the floodplain

All rivers lead to the sea. Well, not necessarily; there are many in the arid interiors of the continents that peter out in salt flats or saline lakes, but the Broadland rivers fit the biblical convention. As their catchments increase in size downstream, more water flows in rivers, more silt is carried to be deposited lower down the course, and the channel widens and deepens to accommodate the flow. It may need huge capacity to carry the winter floods and may have to spill out over a floodplain to do so. The area conventionally considered as ‘Broadland’ for administrative purposes starts as the rivers reach this flood-plain stage and span a distance of a few tens of kilometres to the sea. This administrative convention is misleading and unhelpful, however, in considering and managing the area. The whole of the catchment needs to be looked at if events in the Broads are to be understood, but the floodplain is centre of the Broadland stage. Our sparrowhawk of seven millennia ago has moved over the swamps.

Further reading

There is an extensive literature on the changes in vegetation that followed the retreat of the ice and that developed in previous interglacials, detected through pollen analysis of peats and soils. Sparks & West (1972) is a standard work on it, whilst Godwin (1978) is a very approachable account of changes in the fens to the west of Broadland, written by the doyen of this field. Bennett (1983) and Peglar et al. (1989) illustrate some of the subtleties and complexities that arise from a study of individual sites in Norfolk, and which contribute to the larger picture. Familiarity hides the fact that water is a rather astounding substance and Ball (1999) gives a remarkable account of it. Still the best work on the natural history of stream animals is Hynes (1979) whilst Moss (1998) is a recent account of freshwater ecology in general with substantial attention to streams and rivers. Wright (1995) and Wright et al. (1996) give accounts of the methodology and results of the surveys of British river invertebrates that now form the bases of river monitoring in the UK.