4

Pristine Broadland – Floodplain and Estuary

‘The great marsh lies on the Essex coast between the village of Chelmbury and the ancient Saxon oyster-fishing hamlet of Wickaeldroth. It is one of the last of the wild places of England, a low, far-reaching expanse of grass and reeds and half-submerged meadow-lands ending in the great saltings and mud flats and tidal pools near the restless sea.’

Paul Gallico, The Snow Goose (1941)

Development of the swamps

Picture now what the sparrowhawks saw as they flew, 7,000 years ago, over the Broadland rivers where they widened towards the sea. As catchment areas steadily increase in size from the source to the mouth of a river, more water moves through the channel. If the surrounding rock is difficult to erode, it may constrain the size of the channel and the water must consequently move faster. If there is less resistance, the water widens its main channel and, in the flatter terrain of such areas, spills over a greater area, adjusting its current speed such that it moves rapidly in the middle, barely at all at the edges. There is always some geological resistance and with changes in the geology over quite short distances, the path of a river to the sea can become very varied as it continually adjusts to local conditions.

The Broadland rivers were no exception, though the thickness and softness of the glacial deposits that formed most of the catchments provided no gorges for fast flow, and a subdued topography further smoothed by the erosion of the water flowing off the land. The rivers cut into the Chalk quite deeply at times in the past when sea level was much lower and the gradient was consequently greater than it is now, but these channels are buried beneath the river alluvium that has been deposited since then. There are now very few places where the Broadland rivers still expose the Chalk. The present landscape is one of wide valleys and wooded valley slopes in the upper and middle reaches,. Meanders cut the glacial deposits and the alluvium, and there is a great flat plain where the rivers converge around the Halvergate triangle.

In wet winters natural rivers spread over the full width of their bed, occupying the floodplain to the edge of the uplands; in drier ones they submerge only part of it, but always a substantial area. With the increase in evaporation as summer approaches, they became confined to the main channel. There is an interesting issue of perception here. The river bed is the entire floodplain; what we now often call the river, merely a part of that bed, the summer channel. What has been seen in modern times as undesirable flooding over the valley is, in truth, the river only occupying the full extent of its natural bed, not invading what we have come to view, illogically, as ‘land’.

Catchments are thought of as the ‘upland’ compared with the river valleys. The Broadland uplands are subdued, mostly around 60 metres above sea level, very rarely as much as 100 metres. As they moved down from the upland, the Broadland rivers brought with them particles of debris, both mineral and organic, especially after heavy rain. In the greatest flows they moved sand and gravel along their beds. The gradients were never steep enough nor the flows high enough to move boulders, even had there been boulders to move. As the channel widened into the floodplain, the gravels and sands were deposited first, on the main channel bed or as a bank parallel with it, called a levee. Smaller particles were carried a little further before the current slowed enough for them to fall to the bottom. Beyond that, the water spread sideways over the floodplain, devoid of much suspended matter. And as the rivers widened and meandered in their floodplain reaches a few tens of kilometres from the coast, their upstream heavily shaded ecosystem, dominated by litter falling in from the deciduous forests, steadily changed.

The main river bed remained scoured where flows were highest, but the reduced current at the edges of the channel allowed some submerged plants to colonise, at least until some high flow washed them away. But further from the middle of the channel, the deposited silt and shallower water allowed submerged plants to grow permanently. Silt particles are not inert; they may contain clays and minerals containing phosphorus, or organic debris rich in both phosphorus and nitrogen. They settle to form rich, wet soils for plant growth. The moving and widening channel kept overhanging trees at bay and forest trees such as oak, elm and lime, that had overhung the channel in the upper reaches, could not survive the seasonal flooding. They appeared only on isolated islands on the valley floor where some high flood had piled unusual amounts of debris and where the deposits had resisted the erosion of the moving channel as it meandered, century by century, across the plain.

At the edges of the main channel, where the water depth was a metre or two, water-lilies colonised with emergent reed-like plants where the water shallowed further. Our picture of what the characteristic plants of these reedswamps were, can be gleaned from nineteenth-century photographs (Fig. 4.1) and the observations of early twentieth-century ecologists, who were able to see the processes going on at the edges of the open water before modern impacts had obliterated much of this evidence. Though these pieces of information are really very recent, they probably give a reasonable clue to the dominant plants from much further back, especially when the evidence of recognisable plant remains in the peat laid down in the valleys is also used.

The bulrush (Schoenoplectus lacustris) joined the lilies in deeper water, for it tolerates greater water depths and more exposure from water movements than other reedswamp plants. It was backed by the lesser reedmace (Typha angustifolia) often also called bulrush, and then the common reed, now the most characteristic plant of Broadland, though that would not have been the case before human settlement of the area. There were other species too – clumps of iris or yellow flag, some of the larger sedges such as the pendulous and the saw sedge, and flote and reed canary grass.

Our picture of their detailed distribution is vague, but it must have reflected the different water depths, tidal ranges, exposures to scour, accidents of destruction by high flood and of arrival to colonise, and perhaps also of grazing on young and tender shoots by water voles and coot. The reed is more tolerant of the richer nutrient conditions that were later to develop and has become dominant only recently as a result. The pristine Broadland will have seen big patches of it, but not the huge unbroken swards characteristic of the present day.

Fig. 4.1 The edges of Broads in the late nineteenth century. P.H. Emerson’s photographs show active colonisation of the open water by reed swamp plants, a situation that persisted well into the twentieth century. It is part of a natural succession as the water shallows under the burden of accumulated sediment.

Reedswamp ecology

The productivity of some of these aquatic plants, rooted in sediment, submerged at their bases, but emerging into the air, is very high indeed. On a world scale, tropical reedswamp is by far the most productive of plant communities and the temperate swamps follow not far behind. Their habitat is an ideal one, though not devoid of difficulties with which natural selection has had to cope. Although water itself absorbs a lot of light and submerged plants have considerable problems as a result, emergent species have no such problem. They can store enough energy in their rhizomes (underground stems) at the end of one season to guarantee that their young shoots emerge above the water level in the next. Water is of course no problem for them; though water is the single most crucial limitant for plant growth on land, it is superabundant in a reedswamp.

Nor are nutrients a problem. The silts brought down by the river provide an annually renewed supply, at least for a long period until the catchments become thoroughly leached out over many hundreds of thousands of years. The perennial growth allows a great deal of storage of nutrients in the roots and rhizomes, and annual recycling to the shoots and back again. The problem for the reedswamp plants, however, is in getting enough oxygen to their rhizomes and roots for the roots to function, and in coping with some of the toxic substances produced in waterlogged soils. Plants that are not adapted to cope with these problems, such as crops grown on floodplains, do not survive flooding.

Waterlogged soils, unless they are almost lacking in organic matter and suffused by water currents, are anaerobic; they have no dissolved oxygen. The reasons are simple. Firstly, oxygen does not dissolve to any great extent in water. Oxygen and water are very different chemically and therefore tend to repel. Oxygen is non-polar, it is electrically neutral, whilst the electrons that are present in water, the oxide of hydrogen, tend to spend more time on the hydrogen atoms than on the oxygen, giving it a slight difference in electrical charge from one part to the other, a phenomenon called polarity. Water will readily dissolve strongly polar compounds, such as the major ions, phosphate, nitrate and ammonium, but has less affinity for the less polar, some organic acids, for example, and shuns the non-polar, such as oils and oxygen. Secondly, the small amount, a few parts per million (milligrams per litre) of oxygen that does dissolve, is rapidly used by bacteria decomposing organic matter in wet soil. The supply of organic matter is high because of the high production and the debris of plant growth tends to accumulate as peat, there being little oxygen available for bacteria to break it down.

Reedswamp plants cope with deoxygenation around their roots by tolerating the problem or avoiding it. Tolerance means that their root tissues can survive concentrations of the products of anaerobic activity, usually called fermentation, and akin to what happens to yeast in the brewing of beer. Ethyl alcohol (ethanol) is the main such product. The concentrations that build up are lethal to most plants if they are flooded, but reedswamp plants can survive them or convert the alcohol into something less damaging such as malic acid. Either way the root is handicapped and cannot be very active in absorption and energy transfer, so the plant must have a large root system, each element of which is operating rather slowly. Alternatively, atmospheric air can be pumped down to the roots through a series of air spaces, or lacunae, formed within the plant.

Water-lilies, for example, operate both strategies. Their rhizomes, when broken open, may smell of alcohol, giving the plant the local name of ‘brandy bottle’, but they also transfer air from the leaves at the water surface. In young leaves, especially in sunlight, the air pressure in the spaces between the cells increases as the leaf warms and this pressure is relieved by movement of air down through the air spaces of the leaf stalks (petioles) to the roots and rhizomes. This system cannot work unless there is ultimate relief of the pressure and this is achieved by escape upwards from the rhizomes and roots through the petioles of older and senescent leaves at the surface where insect-grazing has torn holes in the fabric through which air can readily escape.

The bacterial activity of waterlogged soils also creates chemical problems. The bacteria, once they have consumed all the dissolved oxygen, continue to mop up any further supplies that diffuse in from the overlying water, but this is not enough to support a booming population presented with enormous amounts of organic matter. The bacteria (there are many different forms each with specific chemical abilities) thus seek other oxidising agents in the soil water with which to release energy from the organic matter for their growth, or obtain energy from inorganic chemical reactions. They first attack any nitrate available, using its oxygen and releasing nitrogen (the process of denitrification), then oxidised iron and manganese, present in soil minerals, to reduced (and often toxic) forms of these ions. Then they may reduce sulphate to sulphide, again using the contained oxygen. Waterlogged soils thus often smell of hydrogen sulphide and related compounds.

Some of the reduced iron reacts with the sulphides to form an intensely black precipitate of ferrous sulphide that gives some waterlogged soils their characteristic blackness, especially if sulphate was formerly abundant. Finally, organic matter may be reduced by the bacteria to methane or sometimes phos-phines, compounds of phosphorus and hydrogen. These may spontaneously ignite giving ‘wills-o’-the-wisp’ as they emerge as gases from the water surface. Hydrogen sulphide and reduced iron and manganese can be toxic to reedswamp plant roots. One solution has been to allow oxygen, pumped or diffusing down through the system of air spaces in the plant, to oxidise a thin zone around the plant roots and detoxify the immediate root surface. This can sometimes be seen, when the soil is dug up, as rusty red threads of re-oxidised iron in the grey or black matrix of the soil.

The switch from a river bottom, with sands, gravels, twigs and leaf debris, in the bubbling upper reaches, to this very different collection of fine silt deposits, vigorous plant growth and waterlogged soils, leads to major changes in the animal communities. In the silt, deposit feeders, such as the chironomid larvae and oligochaete worms, eat the mud, digesting bacteria from it and defecating the residue for recolonisation. Bivalve molluscs, the mussels, some big, such as swan mussels, others only the size of peas, suck in a stream of water and diluted silt and do likewise.

Like the rooted plants, they too may have problems obtaining enough oxygen, which some have solved by remaining close to the junction of sediment and water. Others produce haemoglobin, which colours some chironomids a bright cherry red and oligochaete worms a dull pink. Haemoglobin binds oxygen and gives a small store, which allows the animals to burrow for a longer time before having to replenish their supply at the sediment surface.

Above the sediment, among the plants, a much more diverse community grazes the softer parts of the submerged plants, though finds better pickings in a rich community of bacteria, algae and protozoa, the periphyton (Fig. 4.2). This coats the plant surfaces, including the stems and petioles of the reedswamp plants and the undersides of lily leaves. These animals include insects – mayflies, caddis flies, dipterans – snails and crustaceans, plus their invertebrate predators – leeches, dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, sucking bugs and beetles.

The reedswamp plants tolerate flooding, though they may grow even better when the water table is just below the soil surface, because of the soil deoxygenation problems. In the main river channel, where there is always water, their prolific rhizomes may intertwine to form floating mats, dependent on the buoyancy given by their air spaces. In Broadland there is a traditional name for these, hover, or hove, and they must have been a feature of the earliest rivers, narrowing the open water and blocking the channel so that water flows were further encouraged to move out over the floodplain.

Fig. 4.2 The periphyton is a complex community that, given chance, coats any underwater surface. Upper left shows a lightly covered plant surface (the epidermal cells are still visible) along with a few oval diatoms (Cocconeis placentula), colonies of tiny bacteria and two protozoon amoebae with their extending pseudopodia, with which they engulf bacteria as food. Lower left shows a denser community with another diatom, Achnanthes (the coffin-shaped objects) as well as Cocconeis, complexes of bacteria and organic matter and, in the centre, a large protozoon, Vorticella. Filamentous green algae, as well as diatoms and a large amoeba, appear in the dense community shown at the right. Photographs and preparation by C.J. Veltkamp. Scale bars are 5 micrometres.

Peat and succession

The high productivity of the reedswamp plants and the inability of the system to decompose all the dead material at the end of the growing season, because of the shortage of oxygen, led to the laying down of peat in the Broadland valleys. Peat is partly decomposed aquatic plant debris, squashed into a deposit by the weight of successive years of accumulation. As the peat builds up it shallows the water and may eventually be eroded away in a high flood and washed out to sea. At the edge of the main channel this would have kept the river open, but over most of the Broadland floodplains very deep deposits were built up. This was true especially from about 5,000 years ago after the sand bar formed at the mouth of the estuary, and the floodplains were less and less affected by tidal erosion.

Throughout Broadland’s history the land has been steadily subsiding and the sea, and therefore river levels, steadily rising. Peat accumulation more or less kept pace with the relative subsidence in the valley floors. Away from the main river channel, fringed by reedswamp, the peat grew and the water shallowed. The water table was soon above the surface only in winter and for most of the year the surface was dry though the soils were still waterlogged a little way below the surface. Plants less tolerant of permanent submergence of their bases were able to colonise. The bulrush and lilies at the river margin were succeeded by reedmace and bur-reed and then a complex of reed, sedges and other species (Fig. 4.3).

The tussock sedge, for example, moved in, a little way back from the channel edge, building up great mounds of old rhizome and leaf bases year on year, until the current year’s growth was maybe a metre or more above the surface. Tussock sedge is a rather vulnerable plant, prone to keeling over if given too much of a push, but it was formerly very common, and many other plants colonised its tussocks, including alder, whose seedlings could establish in the dryer conditions above the reedswamp floor. The plants at first formed semi-floating rafts on the sloppy peat with water hemlock, great water dock, cypress sedge, hemp agrimony, and great hairy willowherb, mint and iris. There was meadowsweet, purple and yellow loosestrife, marsh parsley, bindweed and the now rare marsh pea. Smaller plants, horsetails, lesser water-parsnip, skullcap and even the tiny adder’s-tongue fern also managed to find a niche.

The woody species, alder in particular, as they grew heavier on the tussocks, keeled them over, creating a swampy morass littered with dead wood and irregularly tangled trunks and branches. Such ‘swamp carr’ is perhaps the nearest to the popular concept of ‘jungle’ that western Europe can produce. But as time went on, the peat was building up and the trees were increasingly taking over. The dense summer canopy eliminated much of the ground flora leaving sallows, blackberries and currants, and broad buckler, royal and lady ferns on the damp, darkened floors and alder buckthorn, birch, ash and oak, garlanded with honeysuckle, with the predominant alder in the over-storey.

The great alder forest

Alder and sallow could establish easily on the drier ground beyond the influence of the river channel, where the floods were only temporary. Five thousand years ago, the floodplains of the Broadland valleys thus became a tangle of wet forest, spreading down river as the sand bar strengthened and the sea could not penetrate so far upstream. Where the water flow and tide were greatest, perhaps close to the estuary in the River Yare, the river, and the lagoons created at flood, bore floating mats of reed sweet-grass as their first colonists, perhaps with fringes of reed. This was an unstable habitat. The mats would easily break away under the tide so that few other species had time to colonise – woody nightshade, greater reedmace, kingcup, purple loosestrife, marsh woundwort, common meadow rue and stinging nettle. Eventually, however, the plants got a firm hold in the peat, and reed and reed canary grass established, followed by the alder and guelder rose, privet and forget-me-nots of a subtly different carr – but looking much the same to the sparrowhawk above!

Elsewhere conditions were different. At the heads of tributary valleys, where water flow was small and tidal influence absent, conditions were steadier and there was little impact of new nutrients brought in as silt or in the water from the main catchments. At the heads of the Rivers Ant and Thurne, where the top ends of Hickling Broad and Horsey Mere are now, succession to alder forest involved neither the sweet-grass nor tussock sedge. Low water movement allowed the build-up of firmer peat, low water flow led to a shortage of bases and nutrients. Smaller sedges (Carex nigra, C. lasiocarpa, C. rostrata, C. panicea) survived with rushes, cotton-grass, black bog-rush, purple moor-grass, marsh bedstraw, greater bird’s-foot trefoil, bogbean, common spotted- and southern marsh orchids, and narrow and crested buckler ferns. Where the water was at its most spartan, plants characteristic of acid bogs, Sphagnum mosses and even the occasional round-leaved sundew could grow. Reed and saw sedge were present, but not so prolific as elsewhere, for strong dominance initially needs a high nutrient supply. Alder carr developed eventually as trees established themselves, but it was a more open community than in the more nutrient-rich areas.

Fig. 4.3 The trends of vegetation succession in the Broadland floodplains. The natural sequence culminates in dense alder carr, but cutting arrests the succession, giving reed beds or open fens, which may regress, through scrub to carr, if management is abandoned.

In various subtleties therefore the valley floors were covered by alder forest and it was this that laid down the thick layers of woody peat (brushwood peat) found in the middle sections of the valleys. Seven thousand years ago therefore, before any permanent settlement had occurred, the dense drier forests of the upland graded into equally dense wet forests of the floodplains. There was just a ribbon of open main river fringed by a few metres of reed and lilies to either side and alder forest beyond that, eventually merging with the forests of the upland. Alder swamp carr (Plate 7) is a truly difficult sort of vegetation to cross, for fallen timber on the forest floor alternates with peaty pools and tussocks of sedge. It was impenetrable by boat or on foot in the wet season, and little easier to cross in the summer when the water table had fallen.

Towards the valley margins, where water stood for only part of the winter, the ground was less treacherous, though the floor was, as in all pristine forests, liberally littered with dead wood and relatively dark. It was a productive forest, with trees growing up to 30 metres, not the stunted scrub that alder now forms as a result of repeated cutting, and its fertility was helped by the fact that alder bears nodules containing nitrogen-fixing bacteria on its roots. This was a great advantage in a habitat where nitrate in the soils was continually removed by denitrifying bacteria. As the valley edge was reached the alder forest became diversified with other tree species, oak and ash, lime and birch, until these species began to dominate as the upland was reached and alder became an occasional tree only found in ill-drained spots.

The larger animals of the river systems and floodplains

There is one more component to add to this reconstruction of the pristine Broadland river systems and that is the animal community. Many invertebrates, especially the insects, must have invaded quickly after the ice retreated. For others, such as the flatworms, which move only centimetres a day over the bottom, colonisation of the British Isles is even now not yet complete. Vertebrates also arrived sporadically.

Fish returned in two ways – from the sea and from refuges that had remained unfrozen in mainland Europe to the south of the ice sheet. Among the first to arrive in Broadland may have been those that have both marine and freshwater phases to their life history, such as the salmonids. These fish would have had long passages through the bigger rivers, of which the Broadland streams were mere tributary trickles, before they reached what would become Norfolk, but they swim strongly and can cover huge distances. The Atlantic salmon and the sewin, or sea trout, breed in fresh waters and would eventually have found suitable flinty gravel beds for spawning in the upstream sections of the rivers.

The eel, with the reverse sort of history, breeding, it is thought, in the Sargasso Sea, but living its adult life in fresh waters, would also have been early on the scene, for it can cross the marshy interminglings of watersheds on wet nights and eventually could have had access overland from the Atlantic coast. In the lower reaches the burbot and sturgeon, smelt, flounders, grey mullet and shads would have moved in from the coast somewhat later as the sea filled the North Sea basin and English Channel 8,500 years ago.

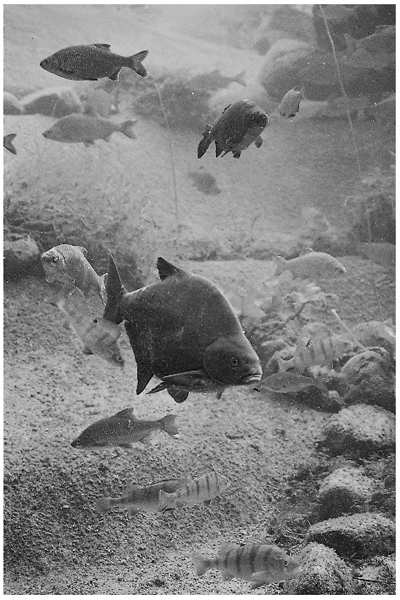

But the earliest fish to move in were probably the freshwater coarse fish that moved up the European rivers. By the time that the British islands were cut off by the sea, about 20 such species had moved in. The native fish fauna of Britain is tiny in number compared with comparable areas of the main continents and this reflects the comparatively short period, only 2,000 years or so, between melting and isolation. Through the early river systems came the typical fish of the more turbulent, gravel-bottomed upland rivers: the brown trout, dace, stone loach, miller’s thumb, minnow and brook lamprey, and the fish of the floodplain reaches: the perch, ruffe, pike, tench, roach, rudd, silver and common bream and the river lamprey (Fig. 4.4). The upstream species need hard substrates for spawning – gravel beds or rocks embedded in the bottom, whilst the floodplain group attach their spawn to plant debris or live plants and can often tolerate much lower oxygen concentrations.

Fig. 4.4 Perch, bream and roach are all characteristic fish of Broadland that would have moved in through the rivers from what is now mainland Europe before Britain was cut off by the rising sea about 8,500 years ago.

In winter they would spread over the floodplain as the waters rose, remaining there to spawn in the tangled debris of the alder forest floors or of shallow lagoons left by the random destruction of unusually high floods. The woody debris offered cover from predatory fish such as the pike and from birds and grass snakes, whilst also providing, as algal periphyton covering its surfaces, tiny items of food that the new young could swallow in spring. In late spring and early summer the fish, old and newborn, retreated back to the fringing reedswamps and main channel as the water levels fell and, as temperatures rose, the remaining pools in the swamp carr became severely deoxygenated.

Birds and mammals

For birds and mammals, the pristine Broadland offered a less varied habitat than it would some millennia later, when the structure of the floodplain vegetation had been changed and varied by human activity, but it was nonetheless hugely attractive. The alder wood offered an extension to the upland forest, the estuary a huge roosting and feeding area for wildfowl and waders, though sheets of open fresh water were confined to the lower parts of the rivers and occasional small lagoons in the alder swamp.

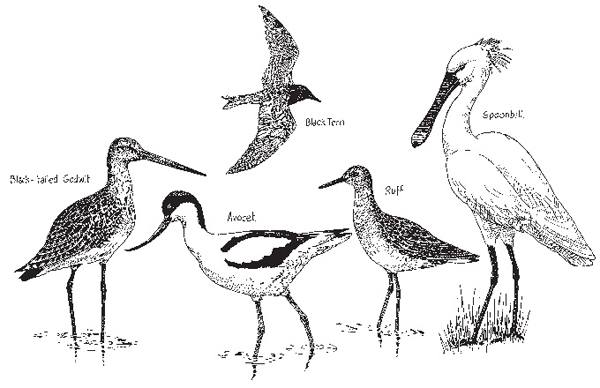

Some species (Fig. 4.5), then present, have not survived the human disturbance of the historic period, but were recorded as late as the sixteenth century or are known from other British wetlands as bones in sediments and peat deposits. Yet other birds, which exploit the consequences of human disturbance, may have been very rare or lacking. Birds are much more mobile than fish, moving in and out of areas in response to quite subtle changes of habitat and climate and it is thus far more difficult to reconstruct their past communities. The lower reaches of the rivers and the estuary may nonetheless have seen flocks of pelicans and spoonbills, avocet, ruff, black-tailed godwit and black tern, all species that have been present, but have now disappeared or visit only rarely. Many species characteristic of open grassland and extensive reedswamps must have been absent or far less common, but those of forest and carr very abundant.

Flocks of tits, the marsh, willow and long-tailed especially, moved through the trees gleaning seeds and insects from the branches and bark crevices; the great and lesser-spotted woodpeckers broke into dying trees for the beetles, demolishing them to furnish the forest floor with more debris for the freshwater community in winter; wren, tree creeper, chiffchaff, blackcap and redpoll likewise took insects and seeds, whilst in summer, the swifts and swallows overhead took advantage of the rich insect swarms emerging from the swamps and rivers.

Fig. 4.5 Some Broadland birds common prior to the twentieth century, now rare.

Bats, the noctule, pipistrelle, Daubenton’s, natterer’s and long-eared caught insects among the trees at night. Tawny and long-eared owls nested in the carrs and hunted water voles, a small rodent sought also by stoat and pike; sparrowhawks, small birds and herons roosted in the tall trees, flying off to feed by the river or in the estuary by day. Kingfishers waited by the stream channels for fish moving to and from the river. Weasels hunted over the sedge tussocks, swimming through pools when they had to, nesting on the tussock sedge and in the lower crooks of trees. Otters abounded both in the wet carrs and in the fringing reedswamps, taking fish, frogs, the bigger molluscs and even the earthworms that grew juicy in the soft peaty debris. Magpies, carrion crows and rooks coped with the bodies of anything dead and large enough to provide a meal, and snipe sometimes nested on the wet floors. Some of the birds that have now adapted to wooded gardens – the redwing, blackbird, siskin, brambling and tree sparrow – found their natural habitats here.

There was a gradual change where the alder opened out into the fringing reedswamp. Here the moorhen and coot dabbled among the grasses and sedges with the water rail, whilst above them, perched on the stems, sedge and reed warblers and the reed bunting sought insects. Kingfishers fished with little and great-crested grebes. Black-headed gulls nested on reed debris where the surface had built up, and in winter the pochard, shoveler and tufted ducks migrated in to feed on the remaining submerged plants and invertebrates of the summer production. Perhaps the bittern and the bearded tit, now well-known unusual birds of the reedswamps, had already established; perhaps they were very common; we can probably never know.

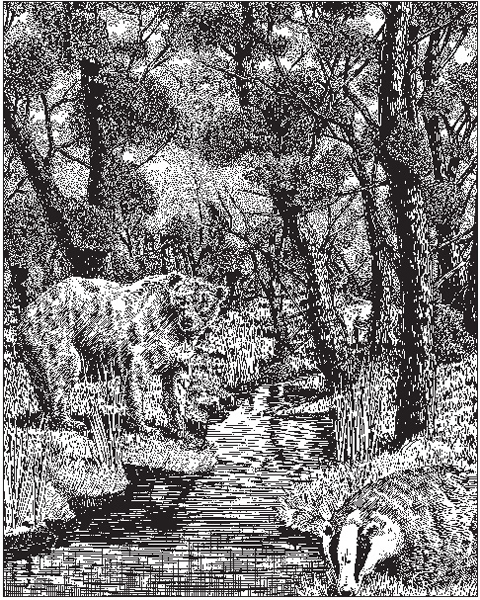

And landward, the large mammals, now gone, but behaving like those of the great pristine floodplain systems of America and Africa, kept to the dry upland in the winter when the carrs were impossible for long-legged species to cross. Then, in spring, they drifted through the tributary stream valleys towards the rivers, feeding on the lush vegetation of the drying floors, the young alder leaves and whatever animal prey they could find. We can imagine the aurochs and bison, the wolf, moose, red deer and the brown bear nosing in (Fig. 4.6). We can imagine badgers, characteristic of well-established undisturbed ecosystems, but few foxes, for these exploit the disturbed habitats created by man. And, in the summer movements of the ungulates (the bones of red deer found in the Broadland peat especially testifying to their abundance), we can see the precedent for the driving in of cattle a millennium or two later by the more settled herders. These were to replace the wandering Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who also followed their prey onto the summer floodplain in search of food and water.

The sea and the tides

Broadland is relatively flat and the gradient of the rivers was never very great in the middle sections and lessened as sea levels reached their highest. At most, the floodplains are only a few metres above mean sea level and at high tides, estuary water still penetrates far upstream. The highest tides bring salt water several kilometres inland, but most tides give a discernible change in water level (called a physical, as opposed to a chemical, tide) several kilometres upstream as the downstream freshwater flow is ponded back by the incoming sea.

Fig. 4.6 Prior to the clearance of the carrs and upland woodland by the Neolithic and Bronze Age farmers, the ubiquitous forest of the Broadland catchment housed animals that have long been extinct in Britain or are now unusual.

Tidal effects are currently quite marked in the Broadland rivers, but present day physical tidal and saltwater penetration limits give us little clue as to the details of the river system 7,000 years ago. The rivers have now been embanked and thus the tidal water cannot move sideways over the estuary and floodplain in the lowest reaches as it would formerly have done. Freshwater flows may also be lower due to water abstraction and greater evaporation from disturbance of the natural vegetation in the catchments. Much of the fringing vegetation at the edge and within the main channels has disappeared, so there is less blockage to tidal flow. The outlet from the estuary through Great Yarmouth is much altered and there is now only one outlet compared with perhaps three or four in the remote past; and we have only vague clues as to detailed changes in rainfall and consequent flows.

In contrast, 7,000 years ago, much of the floodplain was estuarine. Five thousand years ago, following the closure of the sand bar, much more limited volumes of sea water could penetrate the narrowed mouth before the ebb. It is thus likely that tidal effects upstream in the rivers were then lesser than they are now, largely because the tidal water could spill out into a huge area of tidal mud flats and salt marshes behind the sand bar, which lined the estuary to seaward and graded into the freshwater vegetation upstream. Some tidal water must have moved upstream into the freshwater floodplains, but the chances are that this did not penetrate the 20 or more kilometres above the estuary that now regularly experience tidal rise, even if of only a few centimetres.

Salt marshes, mud flats and the estuary

The sparrowhawk had a better view of the ground when she flew down the river valleys and out over the estuary behind the growing sand bar. The reedswamps at the edges of the rivers widened, for alder and sallow are not tolerant of the saltier water close to the coast. The forest was left behind and eventually the reedswamps merged imperceptibly, at first with a greater proportion of the more salt-tolerant flote grass, into salt marshes, and then they too into the open mud flats uncovered at every low tide.

Once, in a Norwich second-hand bookshop, I bought an edition of The Snow Goose by Paul Gallico, illustrated in his early years by the painter and naturalist Peter Scott. It is a moving story and I read it in a single sitting, within the hour, perched on a low wall in the cloisters of the nearby Cathedral. What I remember about it is the sense it conveys of the great salt marshes of East Anglia, a sense of what the marshes of the Broadland estuary would have been like in prehistoric through at least to Saxon times after the turn of the first millennium AD. It is something that cannot be seen today for the marsh has been freshened and drained and remains only as pathetic remnants set at the edges of the larger but still emasculated mud flats of Breydon Water.

Salt marsh and mud flat are among the more productive yet structurally simplest of all ecosystems, subject to the immensely powerful control of the daily tides. At the lower tide levels, where the bottom is covered by water for most of the time and only exposed to the air for short periods at low tide, there are no flowering plants, with the exceptions of some of the sea grasses (Zostera). Prolonged immersion in muddy water, through which little light penetrates, and in a shifting medium for rooting, limits the possibilities.

Algae can grow well, however, and especially in spring the flats are covered by an olive-green or rich brown film of diatoms (Fig. 4.7). Their habitat is a difficult one. There are plenty of nutrients available in the interstices of the mud, but there is also a constant risk of burial in the mud. The diatoms of these habitats are rather boat-shaped, and can move using a structure called the raphe running along their long axis. The raphe is a slit in the silica wall of the cells through which mucilage is extruded. On contacting water the mucilage expands and pushes against the mud particles thrusting the diatom forward. Because the cells respond to light they tend to move upwards at low tide, maintaining their position at the sediment surface.

There are other algae too – flagellates such as the euglenoids, which are green, the red or brown dinoflagellates and a host of tiny green algae, all of which move using fine, hair-like flagella. All grow well in spring and early summer, but their populations fall in midsummer as grazing animals feed. Over the surfaces of the sediment, large numbers of small snails rasp away at the algal film, taking also bacteria, of which there are millions in every cubic millimetre, and organic debris washed into the estuary. The rivers, their catchments, the salt marshes, and the sea on the tide provide copious supplies. From what we presently know of the mud flats of Breydon Water we might guess that the tiny snails Hydrobia ulvae and Potamopyrgus jenkinsii and the familiar winkle Littorina littorea were present. And feeding on these surface snails in winter were resident and migratory flocks of duck – shoveler and shelduck, goldeneye, scaup and tufted. Pochard, mallard, pintail and wigeon joined them to feed on sea grasses and vegetation debris.

Fig. 4.7 Diatoms are important components of sediment and mudflat communities, staining these surfaces a chocolate-brown in spring. Shown are Navicula and Nitzschia species (top right), Pinnularia (top left), Nitszchia sp (bottom left) and the remaining walls of Cymatopleura (bottom right).

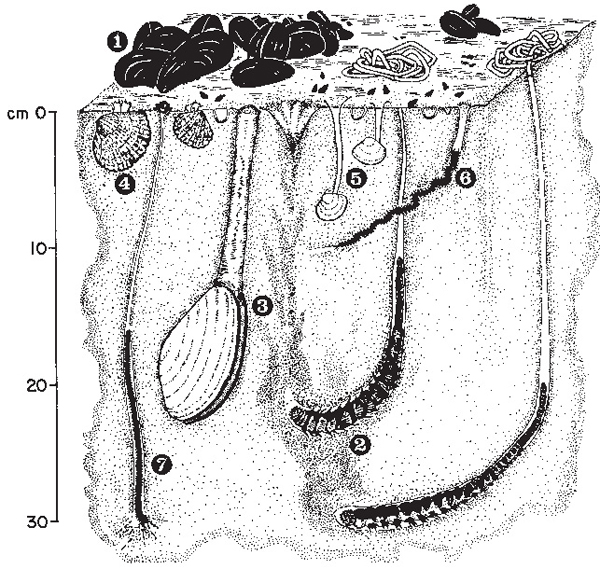

Deeper in the mud were huge populations of a few tolerant species of burrowing invertebrates. Estuaries pose problems for animals because the salinity of the water varies a great deal and this causes difficulties for maintenance of the salt balance within their bodies. Nonetheless, small crustaceans (Corophium volutator, Neomysis integer, Leptocheirus pilosus, Idotea linearis, I. viridis, Palaemon squilla, Gammarus duebeni, G. zaddachi, Jaera marina), polychaete worms (Nereis diversicolor) and bivalve molluscs (Mytilus edulis, Ceratostoderma edule, Tellina baltica, Scrobicularia plana, Mya arenaria) were almost certainly present, dividing the apparently uniform muddy habitat among themselves so as to minimise competition (Fig. 4.8). They do this partly by feeding at different depths in the sediment or by living deep and extending siphons or feeding tubes to the surface. Different species favour slightly different mud textures, some more sandy, others finer and more likely to deoxygenate.

Waders flocked on the mud flats – grey plover, curlew sandpiper, dunlin, redshank, black- and bar-tailed godwits, curlew, whimbrel, spoonbill and avocet – gulls fed on debris and carcasses of fish and molluscs, terns on fish at high water. The division of the spoils among these birds is more readily understood than that among their invertebrate prey. Waders have differing lengths of beak with which to probe the sediment, and exploit invertebrates at different levels and of different sizes. It is one of nature’s great lessons that evolution has tended to minimise competition between species by development of increasing specialisation of food or habitat among different species. Competition is a wasteful business, though prominent among the individuals of any one species in maintaining maximum fitness for the conditions to which it has become specialised.

Fig. 4.8 Mudflats support a very large number of invertebrate animals, though of relatively few species that can tolerate the changes in salinity, exposure and disturbance of the habitat. Some common species from Breydon Water are shown here: 1. Common mussel (Mytilus edulis), 2. Lugworm (Arenicola marina), 3. Mya arenaria, 4. Common cockle (Cerastoderma edule), 5. Baltic tellin (Macoma balthica), 6. Ragworm (Nereis diversicolor), 7. Heteromastus filiformis. Small snails, Hydrobia ulvae, can also be seen on the surface and there are very shallow burrows of a crustacean, Corophium sp. Based on a figure in the 1985 Report of the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research.

Salt marshes grow only at the upper tide levels where the bottom is under water only at the highest tides. Salt-marsh plants suffer the same problems of root deoxygenation as reedswamp plants. Estuarine muds are often intensely black below the surface because there is so much sulphate in sea water that huge amounts of sulphide can be formed. They also have problems of obtaining sufficient water when the source is so much saltier than the sap of their cells. The water must be pumped in against a salt gradient and this requires energy – so much that salt-marsh plants often have the waxy or scaly cover associated with plants of arid environments. Waxy scales give a mealy or rather grey appearance to the plant surfaces, but minimise water loss from the leaves. Other salt-marsh plants are glossy with thick cuticles for the same reason and may even be succulent, such as the samphire or glasswort, apparent refugees from the desert among a plethora of sea water.

The plants also have a problem in resisting the effects of waves and currents and at the lowest tidal levels at which they can survive it tends to be the annual glassworts that are the first colonists. The succulent glassworts give a popping sound when stepped on, hence their common name. Their growth tends to encourage sedimentation and a slight raising of the mud-flat level. They may then be succeeded by other species that can only tolerate less frequent tidal immersion. The sea-purslane is particularly characteristic of the east coast marshes and occupies the lower part of the marsh and the banks of the creeks that drain the water from it as the tide ebbs.

Then at higher levels, which the tide covers less frequently, is a mixture of just a few species – scurvy-grass, sea aster, thrift, sea plantain, sea-lavender, annual seablite, greater sea spurge, sea arrowgrass and the common salt marsh grass. These may form great swards below where the salt marsh merges with freshwater swamps of reed and sweet-grass. The marsh surface is firmer than on the mud flats and will take the feet of large grazing animals; it supports also flocks of swans and geese. The ancient estuary of Broadland would have seen huge flocks of white-fronted, pink-footed and perhaps Brent, bean and barnacle geese as well as whooper, Bewick’s and mute swans, all grazing over the lush pastures from which, on the high tide, quantities of debris were washed out to enrich the mud flats and even the coastal waters. On the tide, young fish moved in – flounder, goby, smelt, eelpout, whiting, pogge, sprat and sole, for the invertebrate food bounty from this rich system was great indeed.

Settled man

The Broadland was a complex system of catchment, river, floodplain and estuary in its pristine state. We can reconstruct only the gross features of what must have been the same sort of subtly patterned patchwork that can be discovered in the few remaining intact wetlands on Earth. There is a satisfaction to be had in contemplation of this system: the steady, parsimonious movement of water, nutrients and organic matter from the catchment to the river; the ways that the river communities processed these materials; the rise and fall of the seasonal floods and their consequences for fish, birds and mammals; the solution of problems of adapting to habitats that were short of oxygen; and the steady laying down of sediments, recording their own history, as peat was deposited in valleys whose water levels also rose with that of the sea. These are the key features of the pristine Broadland, a great forest stitched together by river threads that coarsened towards the coast, where a border of grass and mud fronted the North Sea.

It was not a static system; it responded continually to changes in weather and sea level, but it was clearly a system of connections in which events in one part had consequences for another; in which there were no boundaries, but continual merging as conditions gradually altered from place to place. Modern ecologists would reject any notion of a balance of nature; the system had no grand design beyond a mutual adjustment, through natural selection, to an environment always changing in some minor or major way. Loss of a component, a particular species, would have had little consequence. The resources it had used would have been taken over by some other invader or resident; the ‘services’ it might have provided for others would have been gleaned elsewhere; nothing was ultimately indispensable.

Investigation of any natural system always reveals a myriad of connections and consequences and ultimate adjustment of the survivors. Ecosystems have a built in capacity for this, almost by definition. Sometimes they must cope with glaciation or vulcanism or drought. Since about 6,000 years ago in Britain, they have had to cope with the equally powerful influence of what was to become one of their major parts, that of settled man. The Broadland was no exception. The generations of soaring sparrowhawks, having given us a view of their terrain during the 2,000 years or so from 5000 BC to 3000 BC, when the sand bar formed and the pristine alder forest dominated the freshwater floodplain, were about to start a rougher ride.

Further reading

Hydrology is a well-established area of environmental science, with a considerable specialist literature, but a very readable account of river dynamics, meander and floodplain formation and the like can be found in Leopold (1974). The chapter by Lambert in Ellis (1965) gives an excellent summary of vegetation in Broadland, much influenced by the earlier work of Marietta Pallis (1911) who was one of the earlier British ecologists, working when the vegetation of Britain was being systematically described by Arthur Tansley and his students. Lambert (1951) and Lambert & Jennings (1951) add much detail to the general picture of vegetation in Broadland in earlier periods. Wetlands are now very prominent in discussions on environmental issues and several well-illustrated books, for example, Dugan (1993), give accounts of their interest, beauty and importance. The more fundamental literature on their functioning can be approached through Etherington (1983) and Moss (1998). The specifically Broadland literature is thoroughly covered in George (1992). Ranwell (1972) and Long & Mason (1983) give good coverage of salt marshes, but Teal & Teal (1969) has the advantage of having been written with passion.