8

Broadland from the Normans to Victoria

1066 and all that

The digging of the peat pits that were to become the Broads was steadily progressing. A tentative date for the start of digging can be calculated as the ninth century. This comes from surveys of their fullest extent, the rate at which peat could be removed by the local population in the medieval period, and the records of the floods of the thirteenth century. The Danes thus saw the start, indeed probably made the start, and the Normans saw the end. The year 1066 is (or used to be for older generations) more or less engraved on every British memory as that of the Battle of Hastings, when William of Normandy defeated the Saxon army and went on to annex England. What did this mean for Broadland?

In England as a whole it meant the imposition of a harsh new regime in which a former rich culture was ruthlessly suppressed. A contemporary observer, Odericus Vitalis, wrote that: ‘the native inhabitants were crushed, imprisoned, disinherited, banished and scattered beyond the limits of their own country’. Through a new power group of Normans, French and Flemings, William controlled the land with 5,000 knights and their castles. He began a period in which England would be taxed and exploited and its wealth expended in acquisition through war, then defence and sustenance, of a mainland European kingdom, not finally lost until 1558.

There are advantages in such times to being tucked away in the nether reaches of the land. The rural lifestyle of Flegg and Lothingland, the estuary saltings and the river valleys of Broadland went on relatively undisturbed. Eventually William’s surveyors came around, doubtless meeting suspicion by asking questions about ownership, assets and activities whose answers were to comprise the Domesday Book of potentially taxable property in 1086. In Norwich the newly twinned forces of Church and State were displaying their powers in the form of cathedral expansion and castle-building late in the eleventh century. Word got around that there were new rulers, the coinage had a new head, but the agrarian regime was less affected than that in areas closer to the centres of power. This latest bunch of invaders established a new feudal system with lords, freemen, smallholders, cottagers and slave-like serfs and gained their glory retrospectively, in the usual propaganda of the victors.

Expansion of the monasteries

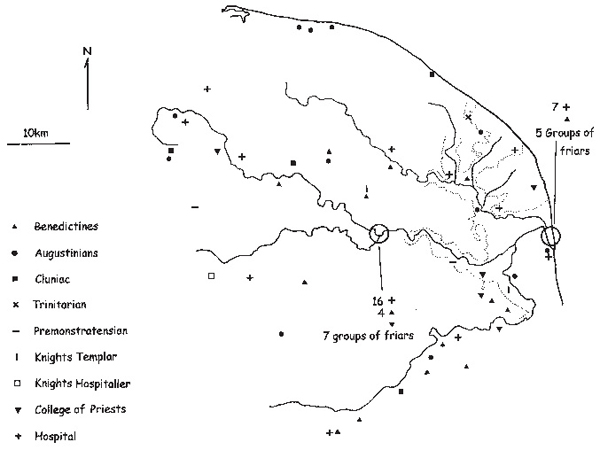

There was nonetheless a tangible influence, not least in the large numbers of churches built in Broadland, and in the establishment or expansion of many religious houses (Fig. 8.1), with their acquisition of lands. They were not necessarily original. The monastery of St Benet’s, in the valley of the River Bure, was founded for the Benedictines in 1019 by the last Danish king, Cnut, nearly half a century before the Norman invasion. Almost every new religious building was based on a previous church.

Fig. 8.1 Monasteries and other religious foundations proliferated in Norfolk, as elsewhere, in the medieval period. Based on Wade-Martins (1994) and Dymond & Martin (1999).

The Broadland expansion has its wetland parallels at Ramsey and Ely in the Wash fenlands and Glastonbury in the Somerset levels. Between 1066 and 1154, the number of religious houses in England increased sixfold to over 300 and the Church then owned a quarter of the land. Monastic houses had gone into decline in the late Saxon period, but were revived by the Norman barons, doubtless fearful for their souls, following the gains of land they had acquired by not entirely laudable means. The isolation of the wetlands allowed communities to be minimally distracted by the secular influences of the town and gave strong defensive positions for communities that accumulated much wealth.

The religious houses were hand in glove with the Norman power base and chose locations with profitable lands to annex nearby; farming wealth was necessary to support communities of several hundreds of people. Broadland houses were founded in the Yare valley at Langley by the strictly vegetarian Praemonstratensians in the late twelfth century, and at St Olaves and Acle in the thirteenth, and persisted until Henry VIII dissolved almost all of them nearly half a millennium hence in the sixteenth century. There were foundations also: at Ingham in 1355 by the Trinitarians; at Haddiscoe by the Knights Templars; at three places by the Augustinians and at seven, including Horsham St Faiths, by the Benedictines.

Little or nothing remains of most of these houses, but where it does, it is impressive. St Benet’s (Figs 1.4, 8.2), by the side of the River Bure, had a huge church with cloisters, gardens, stores, refectories, kitchens, dormitories and chapter house, farms and fish ponds. By one means or another, these institutions appropriated the livings of many local parish churches, placing their monks as incumbents and taking the tithes of the parish into the monastery coffers. These were the agri-businesses of the day. Perhaps in revulsion to values that were perceived as no more spiritual than those of the avaricious Norman barons who had paid for their beginnings, orders of friars arose, groups of preachers assuming a life of poverty, especially in Norwich and Yarmouth, in the thirteenth century (Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.2 St Benet’s Abbey, on the north bank of the River Bure, was one of the great medieval monastic foundations, developed on an island, Cow Holm, in the wetlands between the Bure and the Ant/Thurne. These were connected at the time by what is now the Hundred stream (upper right). The foundation was not dissolved by Henry VIII and the Bishop of Norwich also still holds the title of Abbot of St Benet’s, but the monks left soon after the reformation and the buildings began to deteriorate. Only a small amount of masonry still stands (lower diagram). There are extensive fishponds, where carp and swans would have been kept to provide fresh animal protein in winter. The Abbot’s seal (extreme top left) still exists (in the British Museum). The Arms of the Abbey (top left) represent a pastoral staff between the Crowns of England and Denmark (Cnut financed the original foundation in 1020) and the guiding hand of providence. Based on Snelling (1971).

There was a Norman influence too in that an authoritarian government created conditions for commercial prosperity. Norfolk in general, and Broadland in particular, remained a wealthy and densely populated region, because of the fertility of its soils and the large proportion of independent small freeman landowners. Broadland retained its innovative approach at the ground level.

Farming prosperity

By 1300, a document called the Inquisitones post mortem, a follow-up to the Domesday survey of 1086, but concentrating on manors and lay lords, suggests that land was at a premium in Norfolk. The county was predominantly arable, with arable lands valued at four times those of pasture, and only vestiges of forest remained. Arable values were especially high for Broadland, and maximal, on a national basis, for Flegg. The farming pattern in the Broadland uplands was one of barley, legumes, wheat, cattle, pigs and sheep, with continued innovation in the use of legumes, crop rotations and the use of horses, which work harder than oxen, especially on light soils.

Labour was plentiful and freedom from communal controls helped, together with the urban markets in Norwich and Yarmouth. The Nomina Villarum, a directory of land holdings of 1316, shows land ownership in small units, usually less than 75 acres (30 hectares), compared with a national average of more than 300, except in the Waveney valley, and often with joint owners. A lot of land was at least partly ecclesiastically owned, which tended to increase the proportion of arable.

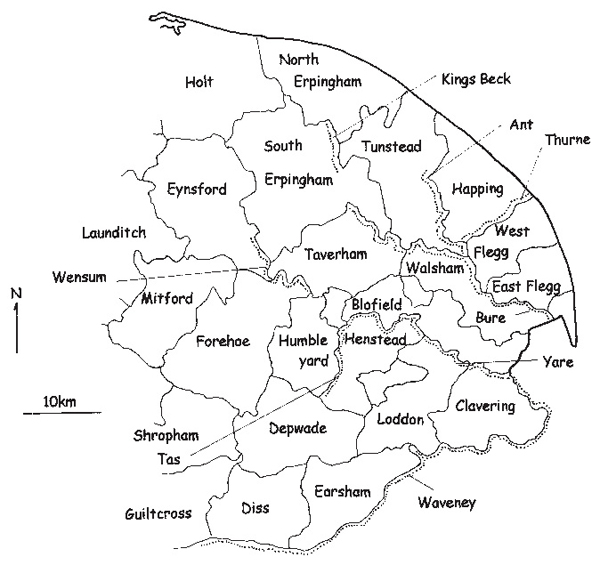

The county was organised into units called Hundreds, each of variable size dependent on the fertility of the land and the taxable income that could be derived from it by the State. Hundreds had been established by the Saxons as the subunits of the counties or shires, and their land was owned by individuals, the King, institutions such as the Church, or cities. They were presided over by a High Constable and a Court and used as the basis for tax collection and military recruitment. The Hundreds of Broadland were small, with boundaries sometimes following the rivers or their tributaries (Fig. 8.3), in stretches that often became known as ‘Hundred streams’ and which allow us to trace some of the former river courses (Fig. 6.1) where they have been subsequently altered.

Broadland villages tended to expand away from a nucleus around the church as owners settled close to their holdings at the edge of the floodplain commons, to hold on to them, if necessary, as populations increased. Norwich and Yarmouth expanded and Norwich (Fig. 8.4) was the second most important city in England. By the thirteenth century it was an important market, industrial and administrative centre with 20,000 people, more than 60 churches and 30 monastic institutions within its walls. Yarmouth depended on a fishery for herrings in the North Sea and on export of woollen cloth (worsted) made locally from the large flocks of sheep.

By 1396, Yarmouth had burgeoned from a fishing settlement to a walled town with 16 gates and ten towers, and had some problems. The harbour, behind the shifting sand bar, tended to silt up and there was a passage of several miles parallel to the bar before the outlet to the North Sea was finally reached. Several attempts were made to shorten this passage, which was treacherous and shallow, but these all failed until 1559. A cut was made that year through the bar at the modern location and strongly piled with timber to discourage the river from re-establishing its natural course. There was much trade up and down river and the navigation reached higher than at present. In 1670 the town of Bungay obtained powers to re-dredge the Waveney between it and Beccles, further downstream, to allow boats to pass; and there were legal obligations for Yarmouth and Norwich to clear encroaching reedswamp in the rivers and to cut weeds to maintain the navigation in the River Yare.

Fig. 8.3 Divisions of the land from the Saxon period were based on ‘Hundreds’ and persisted as administrative units until 1834. The names may often perpetuate the territories of ancient tribal groups. The Hundreds often took streams or rivers as their boundaries, as show here by the dotted lines. There has also been a persistence of the name ‘Hundred stream’ for channels near Martham Broad at the top end of the River Thurne and between the Rivers Ant and Thurne, now abandoned because of diversion of the rivers. (Based on Wade-Martins 1994.

Fig. 8.4 Norwich was very wealthy in the medieval period. The Guildhall, built in 1407, was the seat of local government until 1938, though it was almost demolished in 1908. It was used to confine Robert Kett before his execution and is a prime example of the use of public buildings to demonstrate the power and authority of the State.

There were many Broadland villages, often with charters to hold markets granted between 1198 and 1345 and sold by the Crown. This reflects a steady prosperity over two centuries following the Norman Conquest, but matters were to change again.

Floods and the Black Death

The weather was worsening in the late thirteenth century and the Black Death, bubonic plague, was to cause epidemics of such proportions in 1349 that something of a decline set in. There was an increase in the incidence of gales from the north and north-west. Such gales tend to pile water up in the southern North Sea, causing surges of water up the rivers which, if they coincide with a high spring tide, can mean very high water levels in the Broadland valleys. Some Broadland settlements, for example, at Heckingham and Loddon, moved to higher ground. The higher water tables led to the flooding and progressive abandonment of the peat pits that became the Broads, though the peat trade may have declined anyway as coal was brought in through the ports of Lynn and Yarmouth to meet urban needs.

Fewer markets were chartered following the Black Death, possibly because of population decline, but also because transport had improved. In 1381 there was an uprising of the poor peasants. This Peasant’s Revolt was speedily put down for it threatened the good order necessary for those in power to retain their privileges. But it was the first major skirmish in a trend that was to become one of the most prominent threads of history: change in the balance of power within the population. In Norfolk, a substantial proportion of the dissenters came from among the independent thinkers of Flegg.

The Norman dynasty had, by then, been replaced by the Plantagenets. Kings were often absent in their French domains, with the result that the keeping of financial and other records on parchment rolls began in the King’s chancery and in the courts. This laid yet another foundation for the study of modern Broadland, for it is in the wealth of recorded information that history must be read. There was still great misery. The heavy rains of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries, which led to the abandonment of the Broadland peat pits, also led to failure of harvests, especially in 1315, and famine. The national population of four or five million was not well served by the agriculture of the day, and the bubonic plagues of 1349, 1361, 1369 and 1375 devastated a population already inured to high infant mortality and death by the age of 40. It was also the start of an erosion of the power of the Church, for many of the clergy, faced with a stricken flock, chose to save themselves. Such things are long remembered.

It would, however, be wrong to impute total disaster. Broadland, as it had done following the imposition of the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans, adjusted and modified and continued its day-to-day existence on its fertile loams and on the bounty of its wetlands. It had now the additional resources of fisheries in the Broads, and perhaps greater wildfowl populations to exploit as more open water attracted migrant birds in winter. Some hint of the value of these resources comes in a charter granted to the City of Norwich by Edward IV in 1461 that allowed the City to ‘have search in the river of Wensum [now the Yare] by all the length of the same river…from a certain place on the north part of the City of Norwich, called the sheepwash, unto the cross called Hardele Cross near Bredyng, to survey, and search all the nets weirs and other engines for taking fish being found in the same water…and to take, carry away, retain and…burn all and singular the things…placed or erected there against the destruction of young fish called Fry…’.

The post-medieval period

The Plantagenet kings were at the beginning of a progressive transfer of power to a wider group. They needed funds to pay their armies in the defence of their French and English kingdoms. War protected trade, but as it became more costly, the raising of taxes became more difficult without a transfer of power from the king to the Council and eventually to Parliament.

The Wars of the Roses in the fifteenth century, though appositely named, were merely the minor power struggles among rival families to be king. They had little impact on most of the populace, but the accession of the Tudors with Henry VII in 1485 was a much more significant event. It coincided with the use of printing presses for the first time in England by William Caxton in 1486, thus greatly expanding opportunities for the recording and dissemination of information, but also brought in a new phase of relationships between the monarchy, the people and the Church.

The Tudors, by and large, avoided wars; they established an efficient civil service, through chancellors of repute. They replaced a system of power and influence dependent on private armies by one of patronage and influence in the King’s Council and at court. London flourished; Norwich declined a little, but remained important, but the court, especially by the time of Elizabeth I in the mid- to late-sixteenth century, was moving around the new large houses of the great – and sometimes good. Status was reflected in prominent mansions of brick and oak, with plenty of glass and chimneys, demonstrating the wealth of the family. Gardens were ornate and geometric, reflecting a need for order, both in the face of recent political turmoil, but also in face of what was perceived as a threatening wild nature beyond the boundaries.

East Anglia in general, and Broadland in particular, were still well away from the main routes of communication across country and settled into a backwater existence. The problems of plague and depopulation in the fourteenth century had lead to some increase in the sizes of estates, as farms were cheaply bought by ambitious landowners, but the number of huge estates centred on large country houses was few in Norfolk and fewer in Broadland. That at Blickling (Plate 16) was founded in the early sixteenth century and Langley Hall, Somerleyton Hall and Woodbastwick Hall soon followed, but all are small compared with the eighteenth-century manifestations of power and wealth at Holkham (1734–1761), Wolterton (1726–1739) and Houghton (1721–1735), elsewhere in the county.

Tudor Norfolk was for the most part a county of prosperous yeomen. They built timber-framed houses, often with distinctive rounded gables, thatched at first with the local reed, but by the seventeenth century roofed by new status symbols, pantiles imported from the Low Countries. Huge barns were built in Broadland to store the harvest, with that at Waxham being built in 1581; bullocks became more important than sheep and were fattened in yards on turnips during the winter. The land remained largely unenclosed and attracted high rents, though enclosure of some common land in the late sixteenth century led to riots in Norfolk, led by John Kett. Like the peasants’ revolt over a century earlier, they were swiftly put down. The increasing group of landed rich, now embracing merchants, lawyers and officials as well as the aristocracy, was not about to have its gains threatened. In Tudor times, as ever, the poor were persecuted.

Perhaps the most significant legacy of the Tudor period, however, was the changed relationship between Church and State. Henry VIII, somewhat insecure concerning his right to the throne, like all the Tudors, and needing a strong, male heir, had set in train events that led to the separation of the English Church from Rome. The Roman Church was not popular for, particularly through its monasteries, it had taken a huge share of the country’s wealth and was not a benevolent landowner over the one third of the country it then owned. There was little opposition to the dissolution of the 800 or so monasteries in 1535 and the seizure of their lands and wealth. The abbeys of Broadland, built up since the eleventh century, had had their day by the sixteenth.

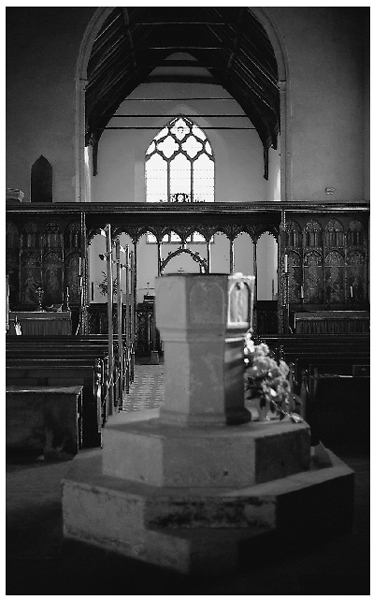

The Broadland churches, like all the rest, were stripped of their painted walls and ornate decorations (Fig. 8.5). Whitewashed walls, simpler ceremonies, the Royal Coat of Arms, the Authorised Version of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer epitomised the new Church of England. The changes were not entirely driven by Henry, for a wave of Protestantism was arising in mainland Europe as well. Nonetheless, they were to have immense impacts through religious strife in parts of the United Kingdom until the present day and represent a major watershed of English history.

When Elizabeth I, the last of the Tudors, died in 1603, she left a society that stressed rank, order, degree and obedience, and in which the way to the top was via influence at the court, ability and office, rather than through the church, as previously it had been. More people, about ten per cent of the population, lived in cities. Elizabeth kept her 60 nobles in check by obliging them to spend money entertaining her in fine houses rather than by spending it on private armies. There was a burgeoning of the gentry. The squire and the parson were the leaders of the parish communities. Land and education had become important; craftsmen prospered. But for most of the population, including that of the Broadland catchment, much was unchanged. It was still largely a populace of subsistence farmers beholden to large landowners, growing oats for fodder, barley for brewing and keeping stock for meat, milk and fertiliser. The landscape was one of woods and greenery, coppices, common and ploughland, some hedged pastures, meadows and parkland, plus the fens and reedswamps of the valleys.

Fig. 8.5 Following the Reformation, the interiors of English churches became much simpler. St Helens at Ranworth epitomises this, but managed to retain a fourteenth-century painted rood screen. It also has a tower from which a fine view of Ranworth and Malthouse Broads and the Bure valley can be obtained.

Tudor fisheries

Fisheries remained important to the ordinary people. John Kett, prior to his suppressed rebellion and subsequent hanging, presented a petition to Edward VI in 1549 that suggests that attempts were being made to appropriate what had been common rights: ‘We pray that the Ryvers may be ffree and common to all men for ffyshyng and passage…We pray that the pore mariners or ffyshermen may have the hole profightes of their ffysshynges…’. There were sensible conservation measures too. The Norwich Assembly Book for 1556 lists regulations for freshwater fishermen in the River Yare: ‘No one to bete in the night time for Perches or any other fish; No fisherman shall put any long netts into the river to take fish there in spawning time, that is to say three weeks before Chrowchmas (May 3) and three weeks after Chrowchmas’. Otters were common, for the same regulations required every man ‘shall be bound to keep a dog to hunt the otter and to make a general hunt twice or thrice in the year or more at time or times convenient upon pain to forfeit ten shillings’.

Yarmouth too, valued its local freshwater fisheries. There exists a 1619 manuscript by Manship that lists eel setts. Setts were nets placed across the river that could be raised or lowered to accommodate passing boats. In 1576, Elizabeth I had written to the town asking that some 35 setts be leased to John Everest, the town water bailiff. The town failed to do this, largely because its clerk was ill, and a local powerful family, the Pastons, attempted to seize the setts for their tenants. The issue became one of the ‘poor fishermen’ versus the rich burgesses of Yarmouth, the relative rights of which are not clear. The Pastons would doubtless have taken a portion of the profits from their tenants. The case was eventually settled, by a commission, in favour of the town. There were restrictions on salmon fishing also, listed in the Norwich Court of Mayoralty Book of 1667, though salmon may not have been common. Sir Thomas Browne, a Norwich physician and naturalist wrote that ‘among the fishes of our Norwich river, we scarce reckon salmon, yet some are yearly taken’.

Sir Thomas Browne and the rise of scientific enquiry

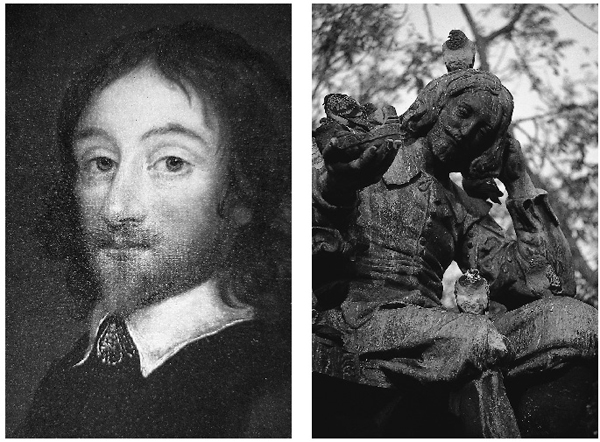

Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) (Fig. 8.6), whose statue stands in the centre of Norwich, close to the market, was a sage of considerable distinction and author of a major discourse on his religious faith and its relationship to his profession of medicine, Religio Medici. His importance to Broadland lies in the records of natural history that he made at a time when scientific classification was only just being rescued from the mythologies of Aristotle. This was the work of Browne’s acquaintance and contemporary, John Ray, somewhat before the revolutionary approaches of Linnaeus in the eighteenth century.

Browne lists cranes (eaten at a dinner given by the Duke of Norfolk to the Mayor) and pelican (shot upon Horsey Fen in May 1663, though he is critical enough to say it might have been one escaped from the King’s collection at St James’s in London). He records the bittern as common. Indeed, he kept one in his yard for two years and was able to counter the then popular belief that the characteristic booming was made by putting their bills in to hollow reeds. He noted ruffs as abundant in marshland between Norwich and Yarmouth. Among fish he describes salmon in the Bure, the Yare and the Waveney, pike ‘of very large size’, bream, tench, roach, rudd, dace, perch, minnows, trout, ruffe (in great plenty in Norwich rivers), lampreys, burbot, gudgeon, miller’s thumb, loach, two species of stickleback, eel and carp.

Browne was one of the group of scientists, though they would not have referred to themselves as such, who, nominally led by Isaac Newton, were to begin the revolution that has led to the understanding of natural phenomena that we enjoy today. But understanding was still very unsophisticated. He was a man of the seventeenth century, when the Stuart kings succeeded the Tudors, bringing with them renewed debate about religion, a further transfer of power to a wider constituency and the horrors of civil war. Births, marriages and deaths were now recorded, the population was more literate; documents had become increasingly complex. But the Stuarts, James I and Charles I and II held to the divine right of kings, did not suppress corruption at court and continued to favour the privileged over the poor.

Fig. 8.6 Sir Thomas Browne was the first of the Broadland scientists. His portrait, painted in 1641, when he was 36, may be seen in the National Portrait Gallery in London and his statue stands close to the marketplace and Hay Hill in Norwich.

The countryside began to change as the influences of building styles, based on classical Roman and Greek themes, penetrated from the continent and were espoused by the Royal surveyor, Inigo Jones. Britain had begun to establish an empire with colonies in America, where the poor and religiously persecuted had fled the hegemonies of alternate Catholic and Protestant dominance in the previous century. Great houses, built in geometric classic styles, replaced the more rambling Tudor mansions, reflecting the uncertainties of a king, Charles II, obsessed with order and discipline. But there were no such mansions in Broadland, which clung to its medieval traditions belatedly tempered by the influence of the Tudors.

There was a trend in the building of duck decoys in which duck were lured by small dogs into long netting pipes set at the edges of lakes. The Broad at Flixton was modified for this in 1652 and decoys were built at Acle in 1620, Buckenham in 1636 and Fritton in 1670. By the eighteenth century Broadland had 15 decoys, the earliest to be built in England, and among the greatest concentrations in Europe. But their use declined in the late nineteenth century owing to foreign imports, dietary changes and greater disturbance of the area by new influences such as shooting and tourism.

Civil war

Parliament was dissolved for a time; the country drifted into civil war on the basis of a religious divide among extreme and moderate versions of Protestantism, but with Parliament hitched to the former, the king and his nobles to the latter. The eventual parliamentarian leader, Oliver Cromwell, came from East Anglia, near Huntingdon, and Parliament held East Anglia. Broadland cannot have been unaffected – by 1643, ten per cent of the male population had been inveigled into one army or another, but the traces are now few. What was good was that censorship of publications ceased with the breakdown of government and new political ideas circulated like wildfire.

In 1659 the army was disbanded (for one thing it was a hotbed of radical ideas) and, in 1660, Parliament was recalled. Little had apparently been gained; the civil war had begun partly over religious tolerance, partly over demands for taxes by the King, but taxation to support armies was even greater. The gentry had found that the underclasses were a greater threat than the King, whom they now saw as a stabiliser to the threat of revolution. But much of more subversive importance had been achieved. There was a rich legacy of new ideas and realisation by the less privileged that there were alternative ways of thinking to the feudalism that still persisted – in mind and in practice. Everyone might eventually have a stake in governance and power.

When Charles II came to power in 1660, royal patronage returned, but there was also a commercial revolution. Navigation Acts were passed to limit the trading activities of foreign ships, a large merchant fleet developed, the slave trade expanded, together with merchant companies in East India and the Levant, and there was an emergence of the professions in a clearer form, including the Universities. New manufacturing techniques had been introduced by Protestant refugees from the Continent, agricultural methods improved, the coal industry expanded and living standards generally rose. Politics became polarised between the conservative, royalist Tory party and the more radical Whigs who put more of their trust in the people. Both terms originally were ones of abuse for minor factions. The civil service began to develop considerable professionalism and the vote was extended to property and office holders. There was commercial dominance, but the lower classes were better off and the Industrial Revolution had begun.

Norwich, for long the second city of the kingdom, began its decline into comfortable semi-rural complaisance, whilst influence shifted to the industrialising towns of the midlands and north. Broadland remained sidelined, continuing its systems and traditions much as before, but the stage was being set for events that would bring to it its current significance.

Isaac Newton (1642–1727) was fomenting the scientific revolution that would replace interpretation of the planet and the universe through opinion and dogma to one based on observation and experiment. God the magician was being replaced by God the great engineer. John Boyle was making sense of gases, Thomas Harvey of the functioning of the human body and John Ray of the relationships between living organisms. The modern understanding of Broadland has its roots in all of these, but apart from the writings of Thomas Browne, little was actually to be recorded of it for more than 100 years.

Conspicuous consumption and the Georgians

The turn of the eighteenth century saw the start of a line of Hanoverian kings. They were helped by the establishment of powerful chief ministers: wheelers, dealers and fixers, epitomised by Robert Walpole, a Norfolk squire, large in body and brusque in manner. For 20 years, from 1721, he managed, through a cabinet of ministers, a network of the elite that gave the gentry peace and prosperity. Trusted by the city financiers, he exerted an economic, social and military dominance that still excluded many Englishmen, and almost all of the Scots and Irish, from any political rights. Money was flowing in from the colonies, which bought nearly half of English domestic products. These interests were defended by military might, in the West Indies, India, Canada and America. The wealth funded development of new tools, new ways of land management and the construction of great houses, hidden in walled parks, yet demonstrating wealth and power in a society that was still hierarchical, male-dominated and dependent on deference.

Land and property bestowed status and the 400 biggest landowners, half of them peers of the realm, controlled the elections to Parliament, supported by a gentry of 15,000 or 20,000, who provided the backbone of parish administration. In Norfolk, whilst the huge pile of Holkham Hall was built on the north coast by Walpole’s family as one of these Georgian monuments to conspicuous consumption, Broadland yet again seems to have missed the tide. Its many small landowners continued a system that must have benefited from developments like crop rotation, and from the profits of investment in the distant industries, but which remained conservative in approach, trusting the known, and now spurning the wildly innovative.

The poor, half of society, remained wretched, and were viewed as an illiterate rabble of labourers, servants and soldiers. Occasionally mob riots erupted against unpopular groups such as Jews, dissenters and Catholics, but most people remained largely deferential to authority, sturdily Protestant, and conservative in their own way. Only later were the news of the French Revolution, and the loss of confidence among the rulers that followed the rebellion of the American colonies, to bring the next step in emancipation. Meanwhile, radicalism in the form of religious movements such as that preached by John Wesley divided the populace. There were those comfortable with the orderliness of the surpliced parson, the whitewashed church, the Royal Coat of Arms, regularity and seemliness, a heaven already on Earth. And there were those seeking change through zeal, self-denial, opportunity, even for women, and work.

For the nobility, the gentry and the middle classes, England was the richest country in the world by the mid-eighteenth century. The wealth was spent on towns and parks, furniture and silver, paintings, concerts and the theatre. Life was centred in the country where the great estates, designed for field sports as well as agricultural production, saw the demolition of labourers’ cottages inconveniently sited for the view from the House. It saw also the enclosure of more land, convenient for the management of new breeds of cattle as well as jumps for the hunts. The Georgians effectively created the present countryside of England, a great landscape garden, sometimes with deliberately built elegant ruins aping the genuine articles of Greece and Rome. There were views across parkland to wilder country: the remaining common land, in the distance, and the farmland disguised behind avenues of trees, copses, and even deliberately built banks. Artificial lakes were popular, crafted to appear as of infinite size. Like Inigo Jones with his late seventeenth-century buildings, Lancelot (Capability) Brown designed an ordered countryside that hid the problems of the poor in a new art form.

The Bill of Rights

The idea of revolution was nevertheless not lost. In 1791 Thomas Paine, following the overthrow of a contemptuous ruling class in France in 1789, published his Rights of Man, a denouncement of a society founded on inherited privilege. The wars that erupted on a huge scale with the French in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries became a great watershed that anticipated the great changes that resulted from the Second World War in the twentieth and which were to be the defining influence on modern Broadland. These wars with Napoleon Bonaparte were costly. Taxes had increased to pay for them and at their end in 1815, with the Treaty of Vienna, huge numbers of soldiers were released back to the job market. There was mass unemployment, made worse by a depression in trade and poor harvests.

Revolution came very close with the decadence of the reign of George IV; political unions arose, demanding universal male suffrage, lower taxation and poverty relief. Uprisings were put down with violence, even massacre. A ruling few still dominated the many and Parliament did not reflect either the distribution or the nature of the population. The chief minister of William IV, Earl Grey (of the tea) was astute enough to realise that the rule of the elite could only be prolonged by major concessions. The Reform Bill of 1831 did not give a universal vote; it applied only to those with a vested interest in the state because they owned property; but it redistributed the seats in Parliament more equably. Together with other liberal Bills, on catholic emancipation, abolition of slavery, the regulation of factories and the commutation of the tithes that had been payable to the Church, it paved the way for a general calm during the reign of Victoria. In that period, Broadland was to emerge in greater prominence from its bit part of the previous seven centuries.

Further reading

Choice of history books can be a matter of taste! There is a huge variety available covering the periods skated over in this chapter. I found Strong (1998) and Lacey & Danziger (1999) extremely readable. Wade-Martins’ Atlas of Norfolk (1994) and Williamson (1997) provide the local historical detail to illuminate the events of the grander national scale. The Proceedings of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society offer interesting antiquarian insights, largely from the interests of one of its editors, Thomas Southwell (1904) in fisheries, and its secretary, W. A. Nicholson (1889) in Sir Thomas Browne. Dutt (1906) also brings together information on former fishery regulations in Broadland.