10

The Rise of Profits, the Start of Decline?

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were key times for Broadland. It was still a backwater, but a flood of national events began to swirl and engulf it. The first inklings had come with the Enclosure Acts beginning in the eighteenth century and with the impetus given to drainage of the grazing marshes by the introduction of mill technology. Over the next 150 years, there was new industry, improved transport, the movement of an increasing population to the towns, water pollution, mechanising agriculture and increasing leisure. These were to be mixed with social changes that gave greater democracy and literacy and development of more governmental responsibility that led to increased legislation and more governmental control of almost everything. Some ingredients of this new mixture were to undermine the natural history interest of the area and, more importantly, to impede attempts to recover it made possible by others.

The Broads – what the sediments tell us

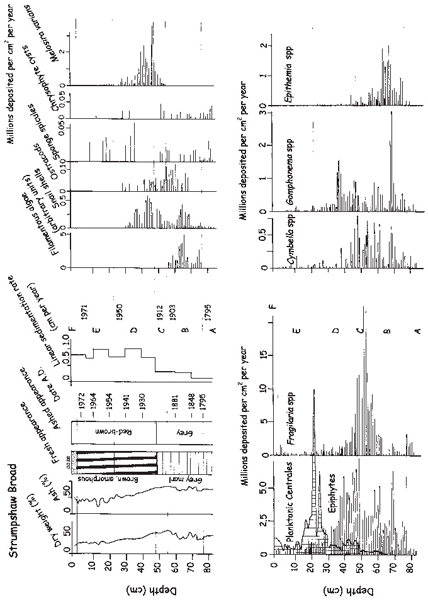

Sediment cores taken from some of the main Broads of the Bure, Ant and Yare show a major change in the freshwater ecosystems in the nineteenth century. The crunchy beige or white sediment, rich in charophyte remains and shells, disappears from around 1860 in the Bure Broads, to be replaced by amorphous dark brown, even black, sediment, still with snail remains, but with a greatly increased organic content (Fig. 7.7). The annual rate of sedimentation began to increase a lot and there was a rise in the numbers laid down each year of a particular group of diatoms, called epiphytes, part of the periphyton community.

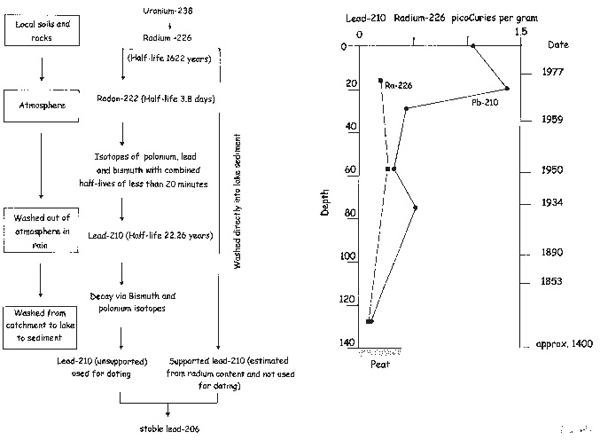

We know when these things happened because we can date the sediment using naturally occurring radioactive isotopes. The best-known way of dating the remains in lake sediments and peats is by using carbon-14. This works very well for the underlying peats in Broadland and is how the dates of the various peat layers are known. The method should theoretically be easily usable to date the sediment of the very recent period as well, except that one of the major changes of that period prevents it. The burning of coal and then oil during the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century and afterwards released carbon dioxide that came from very ancient deposits with scant levels of carbon-14 in them. This upset the natural initial carbon-14 to carbon-12 ratio in a rather random way, so that the initial carbon-14 to carbon-12 ratio in the sediments was no longer constant and this prevents reliable calculations.

Fortunately there are other dating methods that use radioisotopes which can be used for the recent period. Radioactive uranium-235 occurs widely, though in tiny amounts, in many rocks and soils, and very slowly decays to radioactive radium-226. In turn the radium undergoes a series of changes that rapidly convert it to radioactive radon, a gas, which enters the atmosphere and decays, also very quickly, to a radioactive isotope of lead, lead-210. This is removed from the atmosphere by rain and washes into the lakes, ending up in the surface sediment and steadily decaying to a stable form of lead, this time with a short half-life of about 22 years. By measuring the concentration of lead-210 in the surface sediment at successive depth levels, and fitting the concentrations into an equation that describes the course of radioactive decay, it is possible to date sediment back to about 1850 or a little before (Fig. 10.1). After about seven or eight half-lives there is usually not enough lead-210 left in the sediment for present instruments to detect.

Fig. 10.1 Dating lake sediment cores using lead-210. On the left are shown details of the origin of the lead-210. Some of it in the sediments comes from direct wash-in of radium-226 and this cannot be used for dating as the amounts may vary greatly from time to time. The amount of this is called the supported lead-210 for it is present in conjunction with the radium-226 that gave rise to it and a correction can be made. The unsupported lead-210 is that which came in via the atmosphere and the amounts delivered to the sediment each year are much more uniform. On the right is a graph of the amounts in the sediments of core HGB 1 taken from Hoveton Great Broad in 1980. The dates are calculated from the concentrations and also from the density of the sediment to allow for changes in the nature of the sediment and hence dilution of the lead-210 reaching it. Data from Moss (1988).

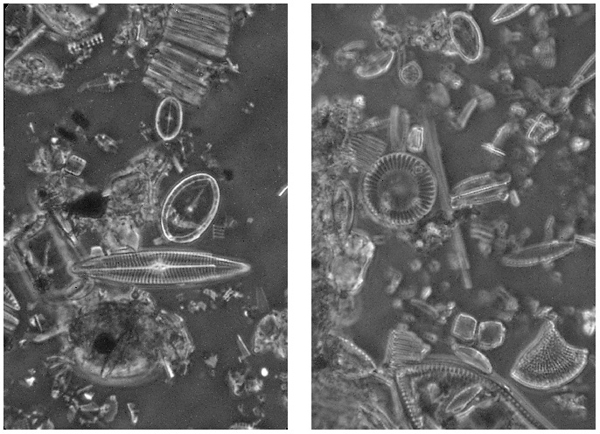

Analysis of diatom remains in the sediment is then used for determining the ecological history of the lake. Diatoms (Fig. 10.2) are exceptionally useful, firstly because they are photosynthetic algae that are very widespread and important components of the algal communities of lakes and rivers. Secondly, they have walls of silicate, like glass, which do not decompose, though they may dissolve chemically under certain, usually highly alkaline conditions. Thirdly, these walls have patterns of holes and slits, which, together with the overall shape of the cell, characterise particular species. And lastly, the attention given to diatom ecology over the past century means that particular species and groups can be used as indicators of ecological conditions and particular habitats. Thus quite a lot can be said about ecological events in the Broads during the last 200 years.

Fig. 10.2 Diatoms from a core taken from Strumpshaw Broad before it was dredged out in the 1980s. Whole diatoms, fragments of walls and inorganic debris remain following heating of the sediment in nitric acid to remove organic matter. Left comes from deep sediment and the diatoms are those of a well-developed plant community (see Figure 10.3). They include the oval Cocconeis placentula, the boat-shaped Navicula radiosa and the chain of Fragilaria cells at the top. Right is from mid-twentieth-century sediment when the Broad had lost its plants and was dominated by circular planktonic diatoms such as Cyclotella meneghiniana (see Chapter 12).

The number of diatoms is quite low in the early parts of the Broadland cores, when charophytes were predominant (Fig. 10.3). Nutrients were scarce in the water and the number of diatoms is an indication of the overall productivity. It is possible that numbers are also low because of dissolution of the silica, but the remains in the cores do not show the blurred edges of dissolving walls. Then, as the charophyte sediments give way to the dark amorphous sediments of the nineteenth century, the numbers of epiphytic diatoms rise, whilst there is no increase, or very little, of the diatoms of the planktonic communities that are found suspended in the water.

Epiphytic diatoms are part of the periphyton, They attach themselves, by stalks or mucilage pads, to the surfaces of plants, where space can become a limiting factor. More diatoms mean more diatom production, and thus an increase in their living space – the surfaces of water plants. The deduction is thus that the crop of submerged plants in the water was also increasing and the loss of the charophyte remains suggests that the plant community had changed in composition. The paucity of planktonic diatoms is consistent with the water remaining clear. There is also an increase in another group of diatoms in the cores at the same time or shortly after the rise of the epiphytes. These are particularly of one genus, Fragilaria, most of whose species live in ribbons on the sediment or among other filamentous algae, such as the green algae Cladophora, Ulothrix or Spirogyra, which form green, cotton wool-like clouds in the water. These too suggest an increase in algal production and thus an increase in the amounts of nutrients – nitrogen and phosphorus compounds – entering the rivers and Broads.

Fig. 10.3 (facing page) Data from a core taken from Strumpshaw Broad in 1976. The variety of information that can be gleaned from such a core is very great. The letters indicate zones of the core where major ecological changes were taking place. During A, the Broad was a clearwater lake depositing marl, and with a plant population, including charophytes, of modest biomass. In the mid-nineteenth century (B), increasing nutrients coming from the disposal of Norwich sewage led to a growth of filamentous algae, greater plant growth (indicated by the epiphytic diatom total and the genera shown at the bottom right), snails and ostracods, which are animals associated with plant beds. In the early twentieth century (C) this process resulted in a continued development of taller plants and a greater growth of unattached diatoms such as Fragilaria and Melosira varians which drape themselves over the plant surfaces or bare sediments. The plant growth was reaching its zenith as the city expanded. In D, the early to middle twentieth century, planktonic diatoms of a group called the Centrales, which has spherical cells, were increasing rapidly and the nature of the sediment changed, with more iron-rich sediment moving in from the catchment as the channels were opened up and the tidal water brought material more easily into the Broad. The sedimentation rate also was increasing and the Broad was filling in. The plankton reached its zenith in about 1950, following a complete loss of the plant communities a few years earlier, shown by the decline in the epiphyte graph. After that (E) the water was too shallow and replaced by the tide too frequently for the plankton to be easily deposited. There are reed fragments in the sediments in this period. By 1974 (F) the Broad was a bare mud flat at low tide and was dredged out to re-establish open water again. From Moss (1979).

The changes and the consequences

New changes in the catchments were being reflected in changes in the freshwater communities, and the changes in the catchments were the results of changes in human society, now documented more thoroughly than ever before. Sir Thomas Browne, his bittern booming in the yard, had begun a process – that of writing down his observations – which added much more information to the story of Broadland. To the records of the sediment cores come the comments, the diaries, the learned discourses eventually given to the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists Society, of a handful of worthy men, each reflecting his own time as well as what he saw. And what was being seen was staggering.

Industry

The rise of industry in Britain was the fundamental change, from which much else followed. It had had its roots in the enterprise of Tudor England, but with more steam and water power in the eighteenth century, the pace quickened. The demands of more organised production, refined skills, timekeeping and consistency of workmanship, led in turn to an ethos of hard work, sobriety and self-improvement in the workforce. There was the confidence given by victory over Napoleon in 1815, a brisk trade with a widening Empire and the promotion of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and the Royal Family as the epitome of domestic virtue. Albert’s encouragement of a fabric of royal pageantry and splendour, grafted onto an otherwise grey industrial world, led to an enthusiastic cadre of entrepreneurs anxious to make their pile and join the established, landowning classes.

Broadland offered no raw materials such as coal and iron that would bring it to the forefront of the Industrial Revolution, but it served the many small industries needed to employ and provide for an increasing population. The fruits of production had led to warmer, securer housing, a more predictable food supply and these in turn to earlier marriage, more children and greater life expectancy. Chalk and lime, bricks and cement, malt and flour were Broadland’s contribution to the populations increasingly gathering in the towns and in Norwich.

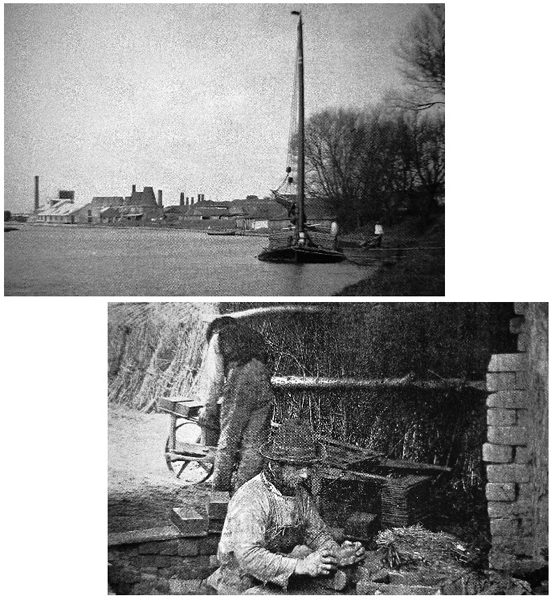

Chalk had been dug out, crushed and spread on the fields since the medieval period, but there was greater need as increased crop production was expected in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In east Norfolk, chalk is deeply buried below the glacial and crag deposits, but reaches the surface, where the rivers have cut into it, between Norwich and Brundall in the Yare valley, and Aylsham and Coltishall in the Bure. Here a large industry arose, with the product, usually quicklime, transported elsewhere by boat. Quicklime is produced by burning chalk, has equivalent neutralising power for soil acids, but is less than half as bulky as the parent material. It can also be used for making mortar and plaster and as a whitewash for walls, which chalk cannot. A lime kiln has been restored at Coltishall on the Bure, and at Horstead, a little way upstream, a confused area of terrain (‘Little Switzerland’) is the remnant of the docks, pits and heaps of the chalk industry (Fig. 10.4). This industry declined as improved transport meant that lime and cement could be produced more cheaply elsewhere.

Estuarine clay and the sandy clays of the soils of the Flegg district were used for brick making. There are nineteenth-century brick pits at Martham, drawing on both sources, which were mixed before firing. Estuarine clay is abundant, but bricks made entirely from it flake and weather badly, whilst the glacial clay is harder to come by and is farther from the river, for transport, but makes better bricks. There were brick works also at Rockland and Surlingham on the River Yare and at Burgh Castle and Somerleyton on the River Waveney, which closed as late as 1939. The Burgh Castle works was built in 1859 and also produced cement by firing chalk with clay, using coal brought in by river as the fuel. Even the Berney Arms Mill on the Yare, responsible for drainage, was used to grind chalk with river clay and mud to be fired as cement.

Watermills also had a role in grinding the grain needed for food. They could not be built in the lower parts of the rivers, for gradients were too shallow to generate enough power, and mill sluices would have interfered with navigation. In the upper reaches, however, they were common, and substantial remains can be seen at Horstead, Burlingham, Chedgrave, Ellingham, Hainford and Ebridge Mill near Honing. In a prime barley-growing area, maltings also were prominent. Barley is malted by soaking and germinating it on extensive floors then heating it slowly to kill it and preserve the sugars produced from starch during the germination. This malt was then sent to breweries for beer making – again using the rivers for transport. Malthouse Broad takes its name from the industry and malt houses remain, though unused now, at Coltishall, Womack, Wayford and, huge buildings, at Oulton Broad and Ditchingham.

Fig. 10.4 In the nineteenth century, Broadland supplied itself with a range of essential industrial commodities, transported by water. The photographs are of the Burgh Castle Portland Cement Company (upper), from Malster (1993) and from a local brickyard, taken by P.H. Emerson.

Transport

One key to industrialisation in the country as a whole, as well as in Broadland, was the development of transport. Since the Romans, road building had been in abeyance. Efficient armies need roads as much as industrialists, but though the seventeenth-century Puritan army had been well organised, civil war does not lend itself to civil works. In the eighteenth century, new roads, the turnpikes, had been established, but not without strife, for the poor populace had to pay to use them. In Broadland, the better solution was to use the more than 100 miles of river and fen-dike that would take shallow-bottomed sailing boats.

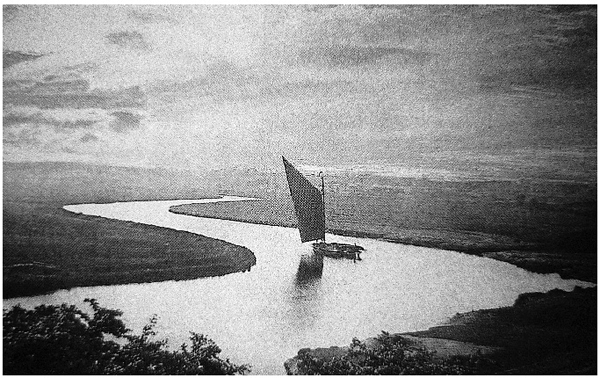

Fig. 10.5 Wherries proved to be a very serviceable design for commercial boats in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and some were converted for holiday hire around the turn of the nineteenth century. They epitomise the apparently slow, steady rhythm of traditional life on the Broads, but the work of moving cargoes of coal, grain, bricks and reed must often have been hard and unpleasant. Photograph by G. Christopher Davies.

Wherries – solid, clinker-built boats (Fig. 10.5) of oak planks, with a big, black, rhomboidal, tarred sail – were the innovation of the seventeenth century and became the quintessential features of many paintings of Broadland in the eighteenth and nineteenth. There were other classes of boat also. Keels, the predecessors of wherries, were smaller, with square sails and drawing more water, but were ousted by the capacious wherries in the carriage of coal, tar, grain, bricks, tar, iron, lime and malt. In the upper rivers, cargoes, especially the harvests of the fens, were taken by smaller boats and transferred to wherries at the many small quays or staithes, where sometimes small warehouses were built. At Stalham, on the River Ant, quite a large complex still stands.

With increased river traffic, and money to be made, issues of navigation and its maintenance became pressing. The Enclosure Acts had supported and often guaranteed existing rights of navigation, but there had previously been only minor recognition of them. There was a Norfolk and Norwich Commission of Sewers, which in 1679 instructed local dwellers to clear weeds by April 1 from the River Bure above Woodbastwick, where it was becoming blocked in summer. By 1722, when the Yarmouth Pier and Haven Act was passed, the Commission could levy tolls on cargoes to pay for keeping the rivers and haven open. In 1860, separate commissions were set up for the Yare, Bure and Waveney, so important had commercial navigation become.

There were also schemes to extend the natural navigation (Fig. 10.6) so that water-borne trade could penetrate further into the upper reaches of the valleys where the larger boats would otherwise ground. They began with the establishment of locks in the 1670s on the Waveney at Geldeston, Ellingham and Wainford, in an attempt, ultimately abandoned, to connect the navigations of the Waveney and the Little Ouse and hence provide an inland route between Yarmouth and Kings Lynn on the Wash. The most successful schemes were at the top end of the River Bure, where in 1779 a canal with locks was built near Aylsham, paralleling the shallow river, and the North Walsham and Dilham Canal that in 1826 extended the navigation on the River Ant by eight miles.

Fig. 10.6 In the nineteenth century, transport and communications in Norfolk were greatly increased. At first it was the river network that was extended (dotted lines) by canals and cuts, but as these were being brought into use, the railways (thin lines) were already veining the land in all directions. Sadly they too met their demise with the rise in road traffic from the 1920s onwards and in the mid-1960s the system throughout Britain was decimated by economic rationalisation. Now few of these lines remain.

The Bure scheme was instigated by the Parish in 1708, when the churchwardens paid out a sizeable sum for ‘viewing and measuring the river’. At that time there was little in the way of local government spanning Parliament and the Parish, which, at an annual Vestry meeting, appointed officers and kept accounts and records. It was not until 1773, however, that an Act of Parliament was passed ‘for making and extending the navigation’ of the River Bure (commonly called the North River) by and from Coltishall and Aylsham bridge. On its completion, which led to some financial problems for the contractor, cargoes could be sent direct to Yarmouth and 26 wherries traded from the town. The locks were damaged in a severe flood in 1912 and it was too expensive to repair them, but remnants of the canal, now overgrown, may still be seen.

Probably around this time or a little before, the River Ant was diverted from its natural, meandering course through the fens to the east of Barton Broad through the Broad itself, thus saving perhaps half a day by a shorter route and a fairer wind. Time has always been of the essence! The Waxham New Cut was a canal extending parallel to the coast from Horsey Mere and built partly for drainage, partly to give access to the brick works at Lound Bridge, where estuarine clay was abundant.

The most prominent new waterway resulted from disputes over tolls between Norwich and Yarmouth, two towns that have almost always had rivalries. In the early nineteenth century, Yarmouth was charging ships, travelling to and from Norwich, high tolls to use its haven. Moreover, cargoes from sea-going ships had to be transferred to smaller boats to navigate the estuary and the lower parts of the Yare, where the channel shifted and could not be permanently deepened. The proposed new scheme was to give Norwich direct access to the North Sea through Lowestoft, then an insignificant village, but a safe harbour.

Firstly, a 1,400-feet long channel was constructed between a small lake, Lake Lothing, ponded by dunes from the sea behind Lowestoft, to Oulton Broad, a little further inland, and then a longer channel, Oulton Dyke, was dug from Oulton Broad to the River Waveney. Finally, the New Cut, a straight channel, two-and-a-half miles long, was dug from St Olaves, lower down the Waveney, to Reedham on the Yare, and the Yare was dredged to nearly 12 feet up to Norwich. There were problems with tides because the Oulton Dyke stretch received two tides, the first from Lowestoft, the second, 90 minutes later, from Breydon Water, so locks were constructed close to the sea at Mutford lock and ships passed through them when water levels were about equal on both sides.

By 1833 this gave a 30-mile length improved for navigation, which bypassed Yarmouth and caused inevitable protest, not only from Yarmouth, but from the owners of the canals at the top ends of the Bure and Ant, whose trade could also be diminished by a greater importance of Norwich. In the end the New Cut scheme was not a success, and Norwich has never really prospered as a port. The New Cut soon became too narrow as ocean-going ships became bigger and the costs of maintenance were greater than the tolls that could be raised. The company that built it was bankrupt in 1847 after only 14 years. There remains to this day a rather ugly, dead straight channel connecting the rivers, an early indicator that the consequences of civil engineering need to be thought through on long timescales.

Commercial water transport in general, though still used on the Yare until the 1970s to supply a sugar beet factory at Cantley, declined in the nineteenth century and died out by the 1930s on the other rivers. Railways and roads were its demise, for they offered faster penetration into the hinterland. The first railway in Britain, from Stockton to Darlington, was built in 1825. By 1850 there were 6,000 miles of track, by 1870, 13,000. Broadland was not left out. The track from Norwich to Yarmouth was laid by 1844, from Reedham to Haddiscoe by 1847 and Norwich to Cromer by 1874. Eventually railways crisscrossed the county (Fig. 10.6), opening Broadland to much greater contact with the rest of the country than ever before and paving the way for the eventual tourist industry of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Remarkably, none of the industrialisation, per se, had much effect on the wildlife of Broadland. It was to be the secondary effects that had the consequences.

Population and urbanisation

The end of the Napoleonic Wars, in 1815, released many men back to the labour market and caused widespread unemployment. The problem was solved by rising industry, which in turn supported further absolute increases in the population, with a major drift to the towns, where jobs were more readily available. Labour requirements on the land were decreasing as more machines were introduced to cultivate, seed, fertilise, harvest and thresh. The population in Britain rose by 73 per cent, two million per decade, during the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1825, only 25 per cent of it was in the towns, but by 1881 this had risen to 80 per cent.

Norfolk was no exception to the trend. Norwich and Yarmouth, and even small towns such as Aylsham, grew, and with them the stresses of public health that resulted from cheap, cramped housing built to exploit as well as to accommodate. In Aylsham, for example, though the water supply was ostensibly from wells, there were still ten or so typhoid cases per year in the parish as late as 1905. Brick-lined sewers had been built to drain the streets since the early nineteenth century, but a report of 1851 found the system very unsatisfactory, with uncovered cess pools, open drains and dung heaps, onto which the contents of domestic lavatory buckets were emptied and eventually washed into the sewers. Unauthorised connections of houses had also been made to the street drains. Effectively the raw sewage of a town that had expanded from about 1,000 people at the start of the nineteenth century to 2,700 by 1851, was discharged to the river. It was not until 1938 that a piped water supply was provided and 1953 that a sewage treatment works was built.

Indeed, sewage, throughout Britain, was commonly discharged raw to the rivers, from which drinking water was also taken. Epidemics of typhoid and cholera were common and greatly feared. The churchyards still show the evidence of whole families obliterated within days. In 1842, the Edwin Chadwick Society produced a report linking illness and premature death with such environmental conditions, but nothing much was done about it for another 30 years.

Sewage and the Broads

The consequences were not only for public health. Sewage, treated or untreated, is rich in plant nutrients. The rise in population and the gathering into towns exacerbated the situation. When the population was small and largely rural, the sewage, one way or another, was spread across the landscape and incorporated by earthworms and other soil organisms into the soil. Some of the phosphorus was held there, some taken up into the food webs and a little leached out to the streams. Likewise, the nitrogen compounds were taken up by plants, denitrified and circulated with again only a little running off into the streams. Most food was locally grown so there was little import of food (and therefore nutrients) and so the stock of nutrients in a given area was held relatively constant.

Urbanisation changed that. Town populations must import food from a larger area, but discharge the concentrated wastes to a much smaller one and that directly to the river with little benefit of soil filtration. The sewage decomposed foully in the rivers below the towns, usually completely deoxygenating a stretch of river completely for a kilometre or two and causing low oxygen concentrations for a much longer distance until decomposition into inorganic compounds – carbon dioxide, phosphates, ammonia, nitrate and others – was complete.

Raw sewage, which includes not only faeces and urine, but cooking and bathing water, would contain as much as 100 milligrams per litre of phosphorus and 300 milligrams of nitrogen per litre. In contrast, the water draining the nineteenth-century agricultural landscape might have had 25–50 micrograms of phosphorus and 0.5 milligrams per litre of nitrogen. Allowing for a hundred-fold dilution in the river, the sewage might thus have increased phosphorus concentrations by 20 to 40 times and nitrogen by six to ten times. Not surprisingly, the main rivers of Broadland became richer in nutrients from the mid-nineteenth century onwards.

Rural lifestyles

On the land, there was no rural idyll, despite the romanticised accounts of the middle-class writers and pictures of the many artists of the time. The Enclosures, though they had increased production by encouraging landowners to invest in new methods and machinery and to drain wet land, at first brought work to the glut market of labourers at the end of the wars, but then reduced them to servitude. Common rights – gleaning of the fields, common pasture on the fens, free fuel and fish – disappeared. Poaching became a way of survival and was severely put down by the Game Laws. It became a capital offence in 1803. One famous case of alleged poaching of eels on Hickling Broad turned on whether the Broad was tidal or not. It certainly is now and certainly was then, but the magistrates, drawn from the gentry, conveniently found that it was not and convicted.

For the first half of the century, the Corn Laws kept high the price of homegrown grain and kept out cheaper imports, favouring the landowners again and depriving the poor, who had little influence over anything. There was a great and patronised gulf between them and the ruling elite. The Reverend Richard Lubbock, a well-connected Norfolk parson, born in 1798, saw the poor through rose-coloured spectacles as he went about a leisured existence that gave him time to write an early classic on British Birds in 1837 and a Fauna of Norfolk in 1845. Riding about his Broadland parishes of Rockland and Bramerton, he became acquainted with those living among the fens:

‘When I first visited the broads, I found here and there an occupant, squatted down, as the Americans would call it, on the verge of a pool, who relied almost entirely on shooting and fishing for the support of himself and family, and lived in a truly primitive manner. I particularly remember one hero of this description. “Our broad,” as he always called the extensive pool by which his cottage stood, was his micro-cosm-his world; the islands in it were his gardens of the Esperides-its opposite extremity his ultima Thule. Wherever his thoughts wandered, they could not get beyond the circle of his beloved lake; indeed, I never knew them aberrant but once, when he informed me, with a doubting air that he had sent his wife and his two eldest children to a fair at a country village two miles off, that their ideas might expand by travel; as he sagely observed, they had never been away from “Our broad”. I went into his house at the dinner hour and found the whole party going to fall to most thankfully upon a roasted Herring Gull, killed of course on “Our broad”. His life presented no vicissitudes but an alternation of marsh employment. In winter, after his day’s reed-cutting, he might be regularly found posted at nightfall, waiting for the flight of fowl, or paddling after them on the open water. With the first warm days of February, he launched his fleet of trimmers, pike finding a ready sale at his home door to those who bought them to sell again in the Norwich market. As soon as the pike had spawned and were out of season, the eels began to occupy his attention, lapwing’s eggs to be diligently sought for. In the end of April, the island in his watery domain was frequently visited for the sake of shooting the Ruffs which resorted thither, on their first arrival. As the days grew longer and hotter, he might be found searching, in some smaller pools near his house for the shoals of tench as they commenced spawning. Yet a little longer, and he began marsh mowing-his gun always laid ready on his coat, in case flappers should be met with. By the middle of August, teal came to a wet corner near his cottage, snipe began to arrive, and he was often called upon to exercise his vocal powers on the curlews that passed to and fro. By the end of September, good snipe shooting was generally to be met with in his neighbourhood; and his accurate knowledge of the marshes, his unassuming good humour and zeal in providing sport for those who employed him made him very much sought after as a sporting guide, by snipe shots and fishermen; and his knowledge of the habits of different birds enabled him to give useful information to those who collected them. These hardy fen-men, inured to toil and privation, were the great supporters of an old Norfolk pastime, as they doubtless thought it – “Camping”. It required muscle and endurance of pain beyond common limits, and somewhat resembled the pancratium of the ancients, but was rather more severe.’

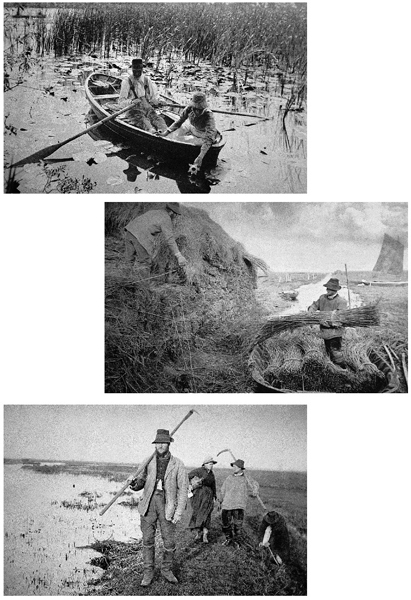

Lubbock was a keen naturalist and aware of changes. He feared for the extinction of the great-crested grebe (shot for its plumes), which was eventually averted by the Bird Protection Act, and noted the filling in of Surlingham Broad, with silt and vegetation, over a span from 1819 until 1875. A few decades later, P.H. Emerson continued the theme of rural romanticism in his photographs (Fig. 10.7), and in 1906, William Dutt continued both that and regretted a decline in the local wildlife. He tells of life on a remnant of fenland at the edge of the Waveney valley, where springs from the upland have prevented ‘the old fen’ from being drained like the adjacent grazing marshes. It is possible that this area is the landward edge of the Carlton marshes, close to Oulton Broad. Dutt describes the lifestyle of an ‘old grey bearded marshman…a man of many occupations – the River Commissioners’ marshman and mill-man, a farmer’s cattle tender and dike-drawer, a reed cutter, an eel catcher, and a flight-shooter.’

He had cut peat in the fen and in his early years there had been an annual race among the villagers to establish who would cut where. Starting in the village, each armed with a shovel, the first to reach the fen would have his choice of where to cut for the season. Flocks of starlings were a problem for the reed cutting for they flattened the reed by their roosting, but the fen harvest was:

‘…nothing now compared with what it once was, and almost every year the stack made of the reed sheaves seems smaller than that of the previous year. For, in spite of what the marshmen say, the old fen is becoming gradually less fen-like, and the time will come when it will be a fen only in name. It has seen the extinction of some of its wild flowers; others which still bloom there are numbered among those the botanists consider doomed to extinction; and, like the reeds, the bogbeans, sundews, and some of the orchids are less plentiful than they were a few years ago. But unlike the fenmen of the Seventeenth century, the marshmen of today make no complaint when they see the swampy lowlands slowly changing into profitable pasture land. They know that the days when a good livelihood could be obtained by wild-fowling, egg collecting, and other fen pursuits are gone never to return, so they behold unmoved the disappearance of the few – the very few – remaining tracts of sodden marsh which remind them of what has been. Indeed they realise that the changes which have taken place and are still proceeding, are to their benefit rather than otherwise, for where the wildernesses of reed and rush provided intermittent occupation for the wild-fowler, egg-collector, and reed cutter, the reclaimed lands must be kept well drained and protected by marsh and river walls, or they cannot be preserved although they are won: and this banking and draining means frequent labour for many hands. So we must admit that the gain is greater than the loss, and that however much we may lament the loss of the wild life and primitive charm of the fen, others will be better for the changes we deplore.’

Fig. 10.7 P.H. Emerson has left us with a picture of traditional activities in the Broads at the end of the nineteenth century. Though carefully posed and conveying more an idyllic view than what was probably a realistic one, they are nonetheless highly informative.

The changes can, to some extent be indicated by the list of animals and plants Dutt casually mentions on the fen in this chapter of his book (Table 10.1).

Table 10.1 Species listed by W. Dutt in a description of a favourite fen in 1906. Species with asterisks are now locally extinct or very unusual

| (a) Butterflies and moths: swallowtail*, meadow brown, five-spotted burnet, convolvulus hawkmoth |

| (b) Fish: eel, roach, bream |

| (c) Reptiles and amphibians: viper, frog, crested newt*, natterjack toad* |

| (d) Birds: reed warbler, water rail*, peewit, bittern*, black-winged stilt*, bearded tit*, grasshopper warbler, pheasant, corncrake*, heron, marsh harrier*, Montague’s harrier*, redshank, reeve*, tern, willow wren, yellow wagtail, snipe, lapwing, lark, meadow pipit, cuckoo, sedge warbler, great reed warbler, ruff*, kestrel, water hen*, swift, swallow, owl, nightjar*, titlark, reed bunting, linnet, starling, goldfinch, fieldfare, redwing, redpoll, green woodpecker |

| (e) Mammals: otter*, water vole, hare, stoat, weasel, field vole, pipistrelle, great noctule bat |

| (f) Plants: bog moss, reed, sedge, rush, greater spearwort, marsh sow-thistle*, fen ragwort, tufted sedge, meadowsweet, marsh orchid, bur-reed, lady’s smock, angelica, jointed rush, marsh stitchwort, dwarf reed, marsh thistle, marsh vetchling, bogbean, bog-myrtle, duckweed, alder, sallow, marsh marigold, flowering-rush*, bog pimpernel, grass of Parnassus, marsh fern, sundew*, spotted-orchid, green-winged orchid*, twayblade*, marsh cinquefoil, marsh St John’s wort, meadow thistle, yellow iris, cat valerian, red rattle, sorrel, oak, water-plantain, water-lily, meadow rue, valerian, dock, bur marigold, water mint, fen parsley and hawthorn. |

What is remarkable about this list is the number of species, indicated by asterisks, that would now be regarded as extremely unusual or very rare.

Fig. 10.8 Eels were an important product of the waterway in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Sometimes they were speared, as in this painting from Dutt’s book; they were more effectively caught in setts, nets laid across the river and tended against the potential damage of boat traffic by fishermen living in ark-like houseboats (photograph by J. Payne-Jennings 1891).

Angling and fisheries

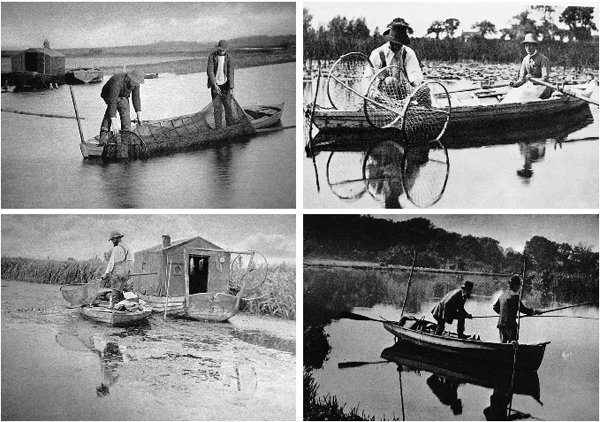

The fishing was, on the other hand, in a good state. This is not surprising. The ingress of nutrients from sewage was increasing the production of plants on the beds of the rivers and Broads, away from the grossly polluted stretches below the sewage outfalls near the towns and larger villages. More weed meant greater habitat for spawning, more invertebrates for feeding. Dutt describes a night spent with an eel catcher on the River Waveney. At the time, eel catchers worked setts, which were walls of netting placed across the river, weighted at the bottom and with floats at the top. They were fitted with long pouches or pokes trailing downstream, into which the eels found their way as they attempted to swim down river. Because of the wherry and other boat traffic, the catcher had to stand by the net to pull on ropes to lower it to the river bed when a boat came by. The best fishing was at night when the eels could not see the net, especially on nights after rain had quickened the river flow.

Catches could be several stones, sometimes 50 or more (311 kilograms) in a night and a succession of catches was stored live in submerged perforated wooden boxes (eel trunks) until there were sufficient to take to market or send to London. Though the supply was supposed to be declining for a number of reasons, including the ‘growing up’ (encroachment of vegetation) of the Broads and the increase in river traffic, eels were still abundant enough to make spearing a feasible catching method also. Flat-tined forks were plunged into the bottom and the eels speared (Fig. 10.8). Eels were also caught on baited lines and other fish, particularly pike, were also accidentally caught. This led to restrictions on commercial fishing with the passing of the Norfolk and Suffolk Fisheries Act in 1877.

There is a lot of anecdotal evidence of heavy fishing in Broadland during the nineteenth century. There had probably been substantial exploitation long before this, as evidenced by pieces of fisheries protection legislation as far back as the thirteenth century, but with the rise in population and urbanisation it may have intensified. It was, at least, documented in the eighteenth century to a much greater extent. As well as the various methods of eel fishing, pike were caught on lines baited with roach and held in mid-water by floating rolls of reed (liggers or trimmers), around which the line was wrapped. Tubular bow nets, held open by hoops, were set in the gaps between the weed beds for tench (Fig. 10.9). Loops of wire were used manually to snare large pike in the clear waters, when the loop could be manoeuvred over the fish’s head and behind the gills. There are descriptions of barrowloads of small fish taken with dragnets being used as manure, and though this can only have been on a small scale it certainly caught the attention of the anglers.

Fig. 10.9 Fishing in general was important in the nineteenth century, both commercially and for sport, when large catches were often made in waters fertilised by sewage. These four photographs by Emerson and Payne-Jennings illustrate different aspects.

There was, nonetheless, no shortage of prodigious angling catches. Two anglers on Wroxham Broad in July 1875 took more than 16 stone (99.5 kilograms) of bream in a single day, so it is difficult to know exactly what the state of the freshwater fish stocks was. The drag netting was said to have been the work of a rather few individuals on the River Yare, using nets 100 yards (91 metres) long and 16 feet (5 metres) deep and often in spring just as spawning was starting, but it was probably more widespread. The anglers were mostly gentry and influential, the commercial fishermen mostly poor and feeding the poor. In 1857 the anglers began to note that netting was extensive and through it rationalised their perceived declining catches. The Field of July 1858 published an article on bream- and roach-fishing in Norfolk. Daily catches were said to have fallen from 20 stone (124 kilograms) or more to ten, eight, even five stones (31 kilograms)!

An Angling Society was convened in Norwich in 1857 and plans were laid to buy out the fishermen on some of the Yare Broads. There were, however, still some common rights of fishing that undermined these plans. The Society berated the Mayor of Norwich for the City not upholding its duties under the charter to conserve the fish granted by Edward VI in 1461 and an Act of George III prohibiting the taking of ‘unsizable’ fish. Eventually, in 1877, an Act was passed under which bylaws were made. The bylaws were very detailed and specific to different sorts of fish. They prohibited drag netting with pokes, any net with less than a seven inch (18 centimetre) mesh (knot to knot), bow nets in the rivers and liggers or snares, except for taking eels. Smelt fishing was confined mostly to March–May in certain locations, but eel fishing (a fish in which anglers were not interested) was largely unrestricted.

Social changes and government influence

Perhaps as much as industrialisation, population increase and movement of people to the towns, the political changes of the nineteenth century were important in determining what was ultimately to happen to the natural history of Broadland. The trends were towards a shift in power from the aristocracy and gentry towards the ordinary people, and the recognition by governments that the impacts of the Industrial Revolution had to be regulated in the interests of health, and ultimately that of the environment.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the aristocracy and gentry had held grimly onto the influence they had acquired since the Norman Conquest, manipulating their funds to take advantage of the opportunities of industry whilst hanging on to the bulk of the land and continuing to dominate the ministries of government. In 1873, 80 per cent of the land was still owned by only 7,000 out of a population of 32 million and, in 1914, one per cent owned two-thirds of it. One third of the population still lived in severe poverty, but the elite were accepted because there was also a sense among them of public duty and philanthropy. It was a religious age of missionary zeal and Christian ethos. It was as the Lord had ordained.

The Crimean War led to a challenge to that and the First World War consolidated it. The invention of mass printing, the sending out of war reporters, the spread of newspapers, all started to reveal some long-concealed truths. The land-owning leadership, though sometimes highly competent, was often useless at maintaining anything but its own interests. Reforms such as the establishment of competitive civil service examinations in the 1870s helped to bring in an ethos of merit over birth and wealth; and the ideas of Charles Darwin, dangerous and revolutionary, brought in concepts of competition and fitness.

The excesses of industry were being felt. Broadland took the consequences of urbanisation, but largely escaped the atmospheric and river pollution and the scarring of the countryside of the north and midlands. The Government evaded the problems. Governments had previously held to a passive role in all but the maintenance of foreign policy and trade protection. Their stance was the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham – in which the State should intervene only to prevent chaos and ensure that enterprise and initiative could flourish. This was all very much to the advantage of its ministers’ and members’ freedom to exploit the nation’s natural resources. In the end, though, environmental and public health conditions became so scandalous that the Government was forced to act and regulate.

Royal Commissions of Enquiry were set up, registers of births, marriages and deaths were established and entry made compulsory in 1874. Statistics were collected and local government organisations were established to manage what could not be overseen centrally. Borough Councils emerged in 1835, County Councils in 1888 and Urban and Rural Councils in 1894, replacing the influence of the Lord Lieutenants and Justices of the Peace, hitherto the agents of the Crown in the provinces. Acts were passed concerning labour, factory conditions, the Church, the railways, the Bank of England, postal services, education and the poor.

Revolution was always distant in the nineteenth century – the masses accepted their lot as inevitable and occasional riots were quickly put down, but one attempt to maintain the status quo was to backfire. Education, originally considered dangerous for the lower orders, for it might give them ideas above their station, gradually became more widespread for it was seen as a means of averting any revolutionary potential. With it, though, came not the intended indoctrination, but a release to question, which was gradually to bring about sweeping changes in society.

The well off maintained the public schools and the previously aristocratic clientele folded into them the newly rich, and inculcated the attitudes of gentlemen, thus preserving the insularity and conservatism that had been the watchwords of the ruling classes for some time. The poor were taught in church-maintained schools at first, but in 1870 it was decided that the State should provide education for all children in its newly founded Board Schools and the State paid for it all by 1891.

Arthur Patterson and Breydon Water

One of the initial problems of introduction of universal education was in persuading the populace it needed it! Arthur Patterson (Fig. 10.10), born in 1857 in the Yarmouth Rows, a district of tightly built slum housing within the medieval walls, had an early career as elementary school teacher, an assurance agent, postman, tea peddler, showman, menagerie keeper and warehouseman. Eventually, in 1892, he was appointed school attendance officer, chasing truants to school. This he did in the light of strong Victorian Methodist convictions for 34 years. But it is in his role as ‘John Knowlittle’ that he is best known. Knowlittle was a pseudonym he adopted in 1896 to write articles and books on natural history for local papers. He used his own name for more formal publications in journals of natural history and, without benefit of any formal qualifications, was eventually elected an Associate of the Linnean Society of London.

Fig. 10.10 Arthur Patterson is justly revered as an observer and recorder of the natural history of Victorian and Edwardian Broadland. He made a few cruises upriver in various boats, including the ‘Yarwhelp’ but was particularly wedded to the life of Breydon Water, with its smelt fishermen (upper right) and punt gunners (lower right).

From his early teens, Patterson hung around the group of people that made their living from Breydon Water. They lived on ramshackle houseboats like Noah’s Arks, a hardy, grim, observant, self-centred and illiterate set of toilers, sometimes far the worse for drink, but carrying on many of the activities documented by Richard Lubbock 50 years earlier (p.162). Patterson recorded them without the filter of romanticism of Lubbock and Dutt. In winter they shot wigeon, mallard, pochard and waders, in spring godwit and knot and in summer spoonbills, sandpipers and almost anything else that flew and could be sold to gentlemen collectors for stuffing and display.

They used large guns (Fig. 10.10) charged with powder and handfuls of shrapnel and shot, from low-lying punts that allowed them to get within shooting distance. The discharge of these ancient and malfunctioning guns sometimes did more damage to themselves than to the flocks of birds. They fished for eels, flounder, then called butts, and mullet in the estuary and sold the lot locally or shipped it to Norwich, Bath or London to be served at the tables of the fashionable and omnivorous.

Patterson recorded what he learned from them and from his own observations on trips in various punts and houseboats that he bought and modified. He collected eggs and went shooting himself at first, but eventually ceased these, though he accepted their role in the local economy and did not disapprove. He corresponded with Eliza Phillips, the founder of the Fur, Fin and Feather Society which was eventually to become the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and may have been influential through this in the drawing up the contents of the eventual Bird Protection Acts. He was also a keen observer of change in the Broadland system during the latter half of the nineteenth century.

In 1902 he was documenting the decline of the punt gunners of Breydon as the bird populations fell. This he attributed to the progressive drainage of the lowlands around Halvergate, a silting up of the remnant Breydon estuary, the expansion of weed (probably eelgrass or wigeon grass) on the mud flats, and the disturbance by commercial traffic passing through. The establishment of a close season by the Bird Protection Acts was the final straw for the punt gunners. The Acts were passed in 1872, 1876 and 1880 by an ethically more conscious late Victorian Society attuned to the ills of industrial expansion – but also careful to preserve the sporting shoots of the gentry.

The poulterers’ stalls, once groaning with duck, dunlin, ringed plover, knot, turnstone, terns and small waders, and even gulls, were no longer so full and the fishing was said to be declining too. Of all the various ills that the system was apparently suffering, it may well have been the very shooting that was most responsible at the time. Another writer, John Gurney, in 1904, noted the very low numbers of coot on Hickling Broad in the early 1880s and a remarkable increase in 1895 following the legal protection of their nests, from which eggs had previously been collected.

Patterson and the Broads

Patterson only rarely ventured upriver from Breydon, but when he did he remained an acute observer. His notes tie in very well with the deductions that can be made from sediment cores taken from the Broads, and from the effects of urbanisation on sewage disposal. In 1919, he took his boat first up the Waveney, then the Yare and the Bure and its tributaries, contributing accounts of this tour to the local newspaper, the Eastern Daily Press. He found the River Yare particularly weedbound: ‘Weeds! I sailed through acres of floating weeds: once went through what seemed to be “The Lake of the Thousand Islands”. Twice I ran on patches and got clear only with difficulty; the oars were like Venetian masts, with streamers.’

It took him six hours of hard rowing to reach Brundall from Reedham, a distance of about 13 miles (21 kilometres). He returns to this issue repeatedly:

‘I must just once more revert to the floating and subaqueous vegetation…The plethora of them has set a motor boatman complaining to me of how often he had to clear his screw: the ferrymen at Buckenham and at Coldham Hall seem to bring them up as a trawl net around the chains and have to stop cranking to rid the links of their fearful gleanings; and my host’s fifteen anglers’ boats lie idle today “folks come but once and not again” he told me.’

Patterson notes in particular the density of weed on the Yare and this may be linked with the greatest discharge of sewage to that river from Norwich, by far the largest town in the area. He talks of the placid, translucent Bure, and the crystal flood above Horning that suggests the water was not turbid, even if very weedy. He knew about the sewers too. In Yarmouth he noted that the water for once was relatively clean: ‘…yesterday it was black, the day before green, red, brown, and so on, exudations from a proximitous sewer opening’. Upstream on the Ant, he was glad of the weed, or at least the water-lilies, for, in what was a very hot summer, he relieved his touch of sunstroke by placing two fresh lily leaves under a towel over his head. Later though:

‘…the Barton weeds; they cloyed my oar blades, they caught in the bows – dead lily leaves, sedges and what not, a queer place for fishermen to cast angle, as some did, only to have their baits held up. It was just then a seemingly hopeless wilderness of vegetable abominations. But my opinions became reversed in the morning when the wind or some more mysterious forces of nature had driven the weeds to the sides, and to my surprise lusty marshmen were hauling it out, and piling it on the shore with long handled, four-pronged forks.’

Birds and people were Patterson’s main interests; he deigns to identify the weed, but the fact that it drifted around in floating masses suggests that it might have been the hornwort, but probably not charophytes, which are always firmly fixed to the bottom. This is consistent with the evidence of the sediment cores, in which Chara disappears, or at least is no longer predominant, in the Broads of the Yare and Bure after the middle of the nineteenth century. Charophytes may have persisted longer in the remoter Ant, as they did in the Thurne system.

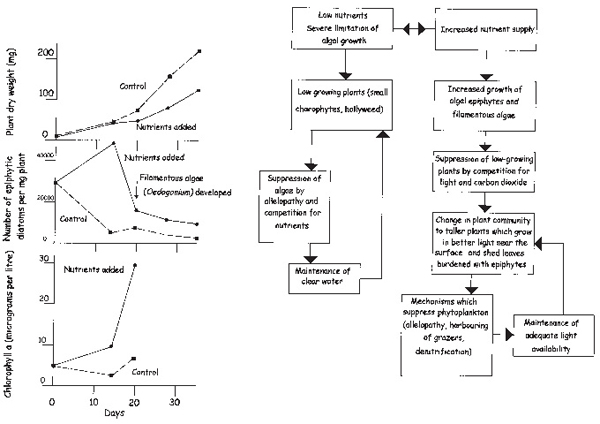

They are associated with low phosphorus concentrations, not necessarily because phosphorus is toxic to them, but because many are low-growing for the most part and soon disadvantaged if other, faster growing plants and filamentous algae or epiphytes grow over them in response to higher nutrient supplies. Several experiments (Fig. 10.11) have shown this to occur with low-growing aquatic plants, including hollyweed, a vascular plant found in Broadland, which has many of the same vulnerabilities as charophytes. Many of the taller vascular plants can also take up nutrients from the water as well as the sediment and as the supply from sewage increased, these would have been advantaged.

Hickling Broad

Charophytes did not relinquish the entire Broadland waterway, however. At Hickling Broad, Chara aspera was recorded by the Reverend Arthur Bennett in 1883 as profuse to the exclusion of almost all other aquatic vegetation and was present with Chara polycantha and Chara stelligera in Somerton (now Martham) Broad. His description has the charm of a leisured middle-class society in the new railway age:

‘So on July 20th 1883, my daughter and I, with Mr A.G. More of Dublin, went to Liverpool Street Station, had tea together, and Mr More saw us off by the mail train to Yarmouth…Finding our way to the Draining Mill below Heigham Bridge, we engaged the lad there and his boat to take us up to Hickling. After passing through Kendal [Candle] Dike into the Sounds, we here and there “dragged” for plants, found many Charas, &c.’

Fig. 10.11 The first effects of increasing nutrient levels on submerged plants are seen in changes in the periphyton (or more precisely, epiphyte) community that covers their surfaces. On the left are shown the results of an experiment in which seedlings of hollyweed (Naias marina), a short-growing annual plant were germinated and grown in low nutrient (control) conditions and with added phosphate and nitrate. The epiphytic diatoms and, a little later clouds of filamentous algae, like green cotton wool, grew in response to the nutrients, and the plant growth was reduced. (Based on Eminson & Phillips 1978). Experiments such as this and observations that epiphytes developed early in response to discharge of sewage to the Broadland waterway (Fig. 10.3) led to development of an earlier form of the hypothesis shown on the right. The low-growing charophytes are replaced by taller-growing plants as a result of the epiphyte development. The original version proposed that an eventual total loss of plants resulted from epiphyte smothering, but such loss is now seen to come from other mechanisms (based on Phillips, Eminson & Moss 1978).

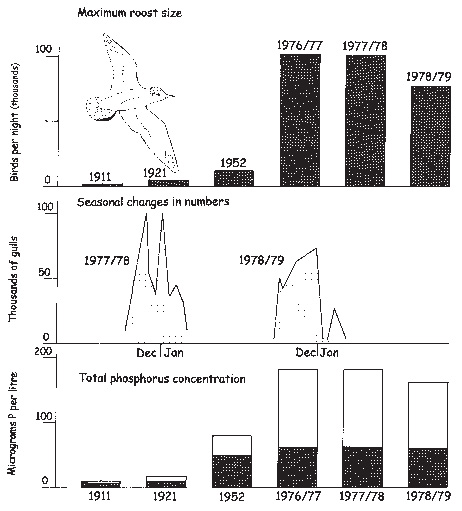

They also found charophytes abundant in Filby Broad, on the Muck Fleet. The charophytes were still abundant in these places and in the Thurne Broads in general, in 1899. All of these locations are at the distal ends of the river system, unaffected by towns or villages of any size. In almost all of them (the exceptions are Martham Broad and the isolated Upton Broad) charophytes were eventually to diminish or disappear in the twentieth century. Nutrient inputs increased from sources other than sewage (a gull roost at Hickling Broad, probably agricultural sources in Filby Broad), but the survival of charophytes to later dates in these locations is notably linked with the absence of sewage.

Fig. 10.12 Hickling Broad was one of the last Broads to show effects of nutrient enrichment and this was owing to an increase in its roost of migratory black-headed gulls. Progressively they came to dominate the sources of phosphorus in the Broad (bottom, shaded areas), with the catchment (unshaded areas) contributing less than half of the total. In the 1980s and 1990s, the gulls, which had been attracted by a close-by waste tip to feed, dispersed, and the Broad has undergone further changes (Chapters 12 and 13).

Hickling Broad and its gulls

A black-headed gull roost at Hickling Broad expanded rapidly in the early twentieth century and the stimulus appears also to have been due to increasing human influence. The gulls were winter migrants, nesting around the Baltic, where their eggs had been collected until protective legislation was passed in the early twentieth century. This was one stimulus to increase, but others were at work. As sea fishing became more intensive, stocks declined and fish were processed on land rather than at sea. Previously the offal was thrown overboard and the gulls followed the boats for it. Lacking fish and fish offal, gulls progressively changed their behaviour and fed much more on land – in ploughed fields and open municipal rubbish tips. Coupled with the other influences, a tip near Martham appears to have resulted in gull roosts at Hickling Broad rising from only a thousand birds each night in 1911 to more than 100,000 by the 1970s (Fig. 10.12). These provided rich sources of nutrients, which progressively increased the biomass of plants in Hickling Broad for two-thirds of the twentieth century, as human sewage had in the rest of the system in the nineteenth.

A last influence – the rise of tourism

Late in the nineteenth century, legislation was passed to provide paid holidays and a working week limited to five and a half days, with statutory holidays (Bank Holidays) on four other days. The railway companies, with cheap excursions, encouraged the idea of the residential holiday and in the 1870s and 1880s the seaside came into vogue. The scene was being set for Broadland’s most important modern industry, surpassing even agriculture: that of tourism – both hedonistic and ecological.

Fig. 10.13 Christopher Davies (1849–1922), an affable solicitor who became clerk to the Norfolk County Council, was the first to publicise widely the attractions of the Broads for fishing and boating, in his writings and photographs. Campbell & Middleton (1999) provide an interesting biography.

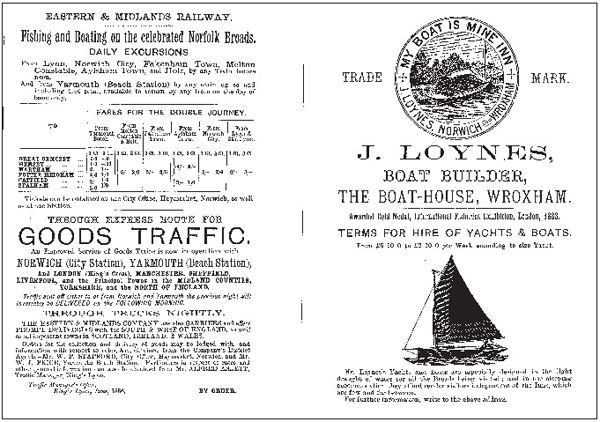

The Broads were well known locally and used for popular ‘water frolics’, an early form of regatta, even in the eighteenth century, and the wealthy kept boats for recreations such as sailing and fishing. Doubtless there was a network of awareness through this, but the Broads were not widely known outside Norfolk until the last two decades of the nineteenth century. The wealthier sections of society were adventurous and keen to exploit new opportunities offered by the railways to get about. Fortuitously, Christopher Davies (Fig. 10.13), a Norwich solicitor who eventually became clerk to the Norfolk County Council, not only had become acquainted with the system, but also enjoyed communicating what he was discovering.

He wrote a short book, published in 1876, called The Swan and her Crew – the adventures of three young naturalists and sportsmen on the Broads and Rivers of Norfolk, which was well received. Then, in answer to many requests that he began to receive for travel information, he wrote a guidebook, The Handbook to the Rivers and Broads of Norfolk and Suffolk in 1882. This book ran to 50 editions over 40 years until his death in 1922. He also wrote a more thoughtful and detailed book in 1883, Norfolk Broads and Rivers or the Water-ways, lagoons and decoys of East Anglia, which ran to 11 editions by 1888. His books were popularising the Broads, listing boat yards where yachts might be hired, and fuelling the abilities of the Great Eastern and other railways to bring people from London to Norwich in less than four hours.

Fig. 10.14 John Loynes, perhaps the first commercial boat hirer on the Broads, advertised in Christopher Davies’ guidebook, as did the railways essential for bringing his clientele to Wroxham.

Others were also copying Davies’ example with their own guide books and over 30 were produced between 1880 and 1900, though all of them very repetitious of each other and romantic in their view – just like most modern guide books! The Broads were being well and truly marketed by a bunch of enthusiastic amateurs, no less effectively than by the hugely paid consultants of the present.

Some cracks were appearing, though, in the idyll of restful waterscapes, abundant fishing and manly sailing. Davies berates some bad behaviour – the bottle shooters, coot potters, noisy revellers, swans’ egg robbers and grebe destroyers – and castigates those young men who failed to confine their nude bathing to before eight o’clock in the morning. But boating on the Broads was a very minor influence compared with what it was to become. In the first edition of Davies’ handbook, only a single boat hirer, John Loynes (Fig. 10.14), advertised, but the numbers were to build up with successive editions.

The boat hire industry

Loynes, formerly a footman at Brooke Hall in south Norfolk, learned to sail on the estate lake, then became apprenticed and eventually a master carpenter in Norwich, and began to design and build boats for his own use. Friends prevailed on him to hire them out from about 1878. By 1882 the business had grown, with a good selection available, some based at Norwich, some at the growing village of Wroxham. ‘Wroxham’ is actually a pair of villages, Wroxham and Hoveton, on either side of the River Bure, north of Norwich, and was to develop as the centre of the boat hire trade. By 1888 the previously open boats had collapsible cabins fitted and the industry was poised to provide greater and greater comfort.

A firm of millers, Press Bros of North Walsham on the River Ant, fitted out five of their wherries, then becoming redundant, as rail replaced water as the major means of transport of goods. They put cabins in the holds, and installed toilets and pianos, at first for the summer only, then permanently. They were hired out, complete with skipper and steward, but affordable only by the upper classes. Eventually wherries, called pleasure wherries, were built specifically for the hire trade and made sleek with smart white sails, to replace the black tarred sails that had characterised the workhorse wherries with their mundane cargoes of grain and coal. By 1891 there were 37 boat-hirers and the centres at Thorpe and Brundall near Norwich, Wroxham and Horning on the River Bure and Potter Heigham on the Thurne were becoming well recognised.

The business was largely in the upper, apparently more picturesque reaches of the rivers, where the Broads were mostly situated. The flat landscapes of the grazing marshes were spurned, except at Oulton Broad, close to the bathing beaches of Lowestoft. Yarmouth stayed rather aloof, or perhaps was spurned by the trade, because it lay beyond the dreary marshes. Advertising expanded and Ernest Suffling, one of the many nineteenth-century guidebook authors, organised the first agency to co-ordinate bookings. Eventually the two main agencies of Blakes and Hoseasons created an efficient structure that not only managed the business, but acted as its advocate as well.

Fig. 10.15 The boats formerly hired on the Broads were mostly sailing yachts. The trend, as the industry has developed, has been towards motorised craft, culminating in the fibreglass hulls of the current fleet.

Fig. 10.16 Development of riverside properties, especially along the Bure between Wroxham and Horning, was at first deprecated, but is now seen as part of the cultural landscape of an area that has seen the influence of human activity for 4,000 years.

Comfort continued to be sought and steam yachts became fashionable, much to the chagrin of the sailing devotees, but even these were rapidly to be superseded by motor cruisers (Fig. 10.15). As the hiring season lengthened from an initial six weeks to an eventual six months, the number of boats increased from less than 50 in 1890, all of them sailing yachts, to 105 in 1920, of which four were motorised. In 1949 there were 547, with 301 of them petrol or diesel-driven, and in 1979, 2,257, of which only 107 were sailing boats.

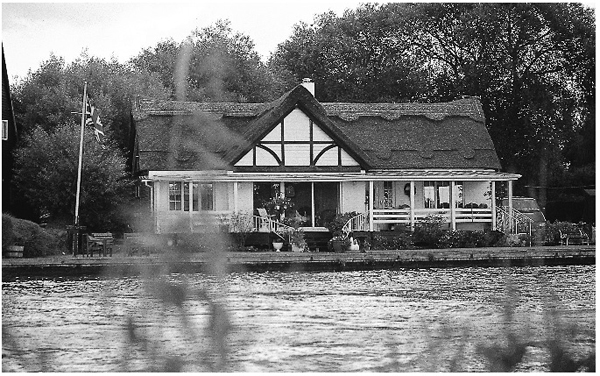

With the increase in the hire trade came a development of land-based facilities. Provision shops, notably Roys of Wroxham, opened in the main centres and would completely equip a hire boat for the week. Especially after the First World War there was a ribbon development of holiday homes (Fig. 10.16) along the banks of the Bure around Horning and at Potter Heigham. These houses were built of light materials on piles or concrete rafts on the waterside peat, and often thatched and timbered in a Tudoresque style. They obscured the view of the marshes and fens from the river, and replaced the reedy fringes with timber or metal protection for their moorings. For many years they were regarded as eyesores, but, their spread having been checked, they are now looked upon more affectionately as yet more symbols of the past relationships between people and the Broads. They also stand as the portals for an intensifying relationship later on in the twentieth century.

Further reading

The continued history of the Broads reflected in their sediments is documented in the references given for Chapter 7 (p.124). More details of dating techniques are to be found in Moss (1998). Stevenson (1879) gives a flowery account of the life of Richard Lubbock, whilst Middleton (1978) and Turner & Wood (1974) tell of the photographers who were using Broadland as a subject in the late nineteenth century and thereby documenting its environment, albeit in a deliberately picturesque way. Tooley (1985) is a biography of Arthur Patterson and the quotations about weeds in the rivers and Broads come from his book of 1920. His account of punt gunning (1902) is typical of his style. Gurney (1904) also begins to document declines in Broadland wildlife late in the nineteenth century, whilst Sapwell (1960) gives a valuable picture of developments in a Broadland town, with particular detail on the sewage disposal. Bennett (1884, 1910) describes the charophytes in Hickling Broad and the development of the gull roost there is documented in Leah et al. (1978) and Moss & Leah (1982). Early guide books to the Broads include Davies (1883) and Davies (1912), which also includes detail on the fishery controversies of the time. Suffling (1892), Goodey (1978), George (1992) and Malster (1993) describe the development of the boat hire industry and Williamson (1997), as ever, is particularly interesting on industrial developments in Broadland. Campbell & Middleton (1999) give a biography of G. Christopher Davies, with reproductions of some of his photographs.