They were moving in slow motion through long, undulating waves of sunlight and shadow. Geneva had not fainted: she had not even felt weak when she reached for him and the brightness came spiraling at her. Rather, she had felt powerful and alive, so alive it made her dizzy. Even now the light swirled around her and made her feel like she was spinning through the warm sunshine. She could feel his arms and his heart beating. She could feel the smoothness of his chest through his shirt, the muscles and sinews under his skin. So heightened were her senses that she could even feel the bones as they moved beside her head. Her ear was pressed against his chest. His heart pounded so that it felt almost painful to her, as if the blood coursed through his heart, then warmed and spiced, into her ear and through her own veins. She felt it moving through her, rising to her lips and groin. She could not stop the sound of the blood thrumming through her ears, or the rapid pulsing of her heart. Nor did she want to. It was a wonderful awfulness: she would have wept with joy or fear or pleasure if she had felt it in her power to do so. But she was stunned into immobility, as if his blood mingling with hers had rendered her unable to act on her own emotions. She was no longer her own self, rather she seemed to have become a part of this man who held her so close. They were one: floating, swirling, eddying in the sunshine through the majestic forest.

Howard laid her on the bed and washed her face with a cool, wet cloth.

“Oh, Lord God, Geneva. I’m sorry,” he was saying. “I shoulda known better than to have ye out there aworkin’ like that. Yew jist seemed a lot better, and I didn’t realize that pannin’ would strain ye. Kin ye talk? How do ye feel?”

She smiled at him through a golden mist. She was still giddy, still swirling. What was it? The gold? Howard? It didn’t matter. She sighed and lay back, enjoying the memory of the moment when she felt herself rise and take flight in his arms.

Then something clicked into place. She saw the concern in his face, and shame flooded her. Silently, she prayed that he had not seen what had been in her thoughts when she lifted her arms and clasped them around his neck. “Oh, God, I’m sorry Howard. I’m all right. I just got hot.” Her face reddened at the unconscious innuendo. “And all that rushing water. I’m sorry,” she said again. “I scared you.” She pushed back the hair falling into her face. “I’m fine, really.”

He jumped up. “Let me git ye some more water.” He handed her yet another cupful of the cold, clear water redolent with herbs.

“What is this?” she asked, sipping.

“Comfrey, a little fennel. Hit cleans out the blood.” He stroked her hair. “I thought yer fever was gone, but you’re flushed, and ye feel a little hot now. Ye got some bug, and till ye git over it, ye’ll have poisons in yer blood. This’ll do the trick, this and a little rest. Ye’ll be fine by tomorrow.”

She believed him, or rather, wanted to believe him. She hoped he was right. She had some little bug, and that, combined with the dizzying water, had made her swoon. That was all. But she trembled again at the smell of him when he leaned toward her. “Be careful!” a voice screamed in her head. She shook herself and schooled her thoughts.

“Howard, how do you know so much about the healing properties of herbs? Did Lenora teach you?”

He settled on the nearest stump. “Some. My mama taught me some, too. But I learned most of what I know from my great-grandfather. He was a healer among his people. My mama died when I was fifteen. That’s how my dad lost his legs—they were in a car wreck. I went to live with my mother’s people out in Oklahoma fer a year after the wreck. My dad was in a coma for months, and then he had to go to Harrisonburg for rehabilitation. When he was gone, I felt sort of in the way here. Lost, I guess, and I missed my mother. My grandfather asked me to come live with them for a while.”

“Your grandfather was a healer too?”

“Mostly my great-grandfather. He was the official medicine man in his tribe. He was real old when I went out there, and he remembered the old ways. His father wuz born in North Carolina at the time when the Cherokee still claimed all the land in the Blue Ridge and Nantahala. When he was five years old, him and all his family wuz run out. They walked all the way to Oklahoma.”

“You mean he walked the Trail of Tears?” Geneva had learned about that event in history, not from the classroom, but from Walk in My Heart, the third book sent from the Romance of the Month Club she had long been a member of. It was a novel about an Indian princess whose lover had been a soldier in the American army. She had read it twice.

“Yes. My great-grandfather learned healin’ ways from his father, and he taught his children, but it was my mother who took the most interest in it. Of course, I didn’t pay much attention to her when she tried to teach me. At that time I was more interested in the things of white men: fast cars, hamburger joints. But when I went to live with my grandparents, I found out what it meant to be Cherokee, and it… changed me.” He let his eyes drift toward the window and stared at something far in the distance.

She sat up. “How long did you live with your grandparents?”

“Jist a year. As Dad got better, I figured I oughtta be here, takin’ care of him. I got an older brother, but he wanted to go to college, and he had stayed with Dad while he wuz so bad off. So I came on back home. Mammaw and Pappy, they wanted me to go back to school, but I’d spent a year livin’ outside, bein’ in the woods and in the hills. Now I can’t stand bein’ cooped up. No way I could sit in a school house all day.”

“But you’ve been cooped up here. You’ve hardly been outside at all, and you haven’t seemed to mind. You sat up half the night reading. I’m surprised you didn’t want to go to school.”

He glanced at her mischievously. “Who wouldn’t mind bein’ cooped up with you, Geneva? I reckon there’d be men willin’ to fight fer that privilege.”

She dropped her eyes, cheeks flaming. “I better go shoot us some dinner,” he said quickly. “Yew want more squirrel, or maybe a turkey? Or fish. Hit’s a regular supermarket out here.”

Rising, she crossed to the window. “Fish,” she decided. “You have a fishing pole? I’m a pretty good fisherman myself, and I feel like just sitting by the creek.”

“No fishin’ poles. I catch ‘em the fun way. Yew really feel better? Kin ye come to the creek? I’ll show ye.”

It was a perfect day for dalliance. The mountain trout shimmered silver in the water. The sun rained down gold, and Geneva sat by the creek and combed her hair with her fingers. Howard, his pants rolled up, waded into the water after a big trout lurking in the rock pool. Laughing silently, Geneva pointed to the shadowy place where the creature lay, and quietly, stealthily, Howard crept upon it. Then, with a motion so slow that he seemed to be drifting with the current, he dipped his net into the water and scooped up a fish so big Geneva knew they both could feast on it.

She was feeling stronger, although a bit shaky, but she wanted to be useful, so she built the fire while Howard cleaned the fish. As they peeled and pan fried potatoes and onions, she felt her appetite return.

Supper, served al fresco under the deepening sky, was tasty and companionable. Afterwards, they dangled their legs off the porch, watching the sky turn from deep blue to black and the moon rise high and round.

“Boy, oh boy,” sighed Geneva as she leaned against the support pillar, “I just need one thing to make this a perfect day.”

“What’s that?” mused Howard. “Dessert? There’s huckleberries over yonder. I reckon we could make us a pie.”

“Gosh, no. I’ve eaten enough. What I really want is a bath. And a brush. And some shampoo.” She warmed to the memories of personal hygiene. “And a real toothbrush with toothpaste. Those sticks you give me to chew are okay, but I’m beginning to feel awfully dirty. And where do you wash your clothes?”

“Over in the creek, and I bathe there, too. There’s a big swimmin’ hole jist below here, right by where I git th’ mint. Hit grows wild all over, and the place always smells of it. Hit’s real perty there.” He frowned. “But I don’t reckon yew oughtta git in the creek,” he added. “No sense in you takin’ the chance of makin’ yerself sick again. We’ll see how ye do tonight. If ye don’t chill, maybe ye kin jump in fer a swim in the mornin’.” He looked at the fireflies and added. “I reckon we’ll head on back down the mountain tomorrow. Ye’ll surely be strong agin’ by then, and we don’t want yer folks to come home and worry.”

“That’s true,” admitted Geneva sorrowfully. She wished she could stay a little longer. It was so beautiful here.

“But if yer set on havin’ a bath, I kin heat ye some water up from that rain barrel, and ye kin git right down in it. I ain’t got shampoo, but I kin mix ye some soaproot and laurel tea. Just as good. Better.”

“Oh, Howard, would you? A bath would be wonderful. More than wonderful,” she sighed.

The rain barrel was already full from last night’s deluge, so Howard poured the water into a huge zinc washtub, big enough for Geneva to sit in, and built a fire under it to heat it. In the high altitude, it boiled quickly, just at the right temperature to steam in the cooling night.

“This oughtta be jist right,” he announced. “Ye cain’t git yer coffee hot enough, but boilin’ temperature’s about right fer a hot bath. Now you git on in before it cools off, and I’ll run over to the creek. Bet I git cleaner’n yew do.”

The word “pleasure” took on new meaning to Geneva as she sank into the water. Lying back, she watched the steam rise toward the stars and listened to the frogs singing their nightly chorus. They textured the lonely darkness with their cries. A whippoorwill called for his lost love, then called again and again. His voice seemed forlorn and lonely.

She lathered her hair, then soaked in the water redolent with wild ginger and wintergreen until the moon changed from her yellow robe to her white one and the water cooled. When she emerged, feeling refreshed and cleansed, she dressed in one of Howard’s flannel shirts, which hung nearly to her knees. Although she was feeling a bit sleepy and ready for her perfumed pillow, she took the time to wash her own shirt and underwear and hang them on the porch railing to dry. She would wear her own things home tomorrow.

Howard had not returned by the time she entered the cabin. She chuckled to herself, thinking of how she would tease him about lingering so long in his beauty bath. Shivering slightly, she wondered how anyone could spend time dawdling in that cold water. She sat down to wait. He would be here shortly.

He did not come. She looked out the window, but saw nothing except blackness, and she began to grow a little concerned. Surely he was on the trail back by now. She would just step off the porch and call to him.

“Howard?” she called from the porch. There was no answer. She walked a little way down the trail and called again into the night. All she could hear were the roaring sounds of the night creatures and the water rushing down the mountain. She would go as far as the edge of the mint bed and call again, she decided. What could be keeping him so long?

The moon lit her path and gave her confidence as she strolled through the chilly air. The creek lay to her right, but the water was swift here. He had said there was a swimming hole on down. No doubt it would widen and grow quieter. She stopped when she smelled mint. Knowing she was close, she opened her mouth to call to him, but when she lifted her face, her breath caught in her throat; her voice stilled.

He was standing naked on the top of a cliff on the opposite bank at least twenty feet above her head. His arms were stretched out low and slightly behind him; his back and neck were arched, while his face gazed up into the full moon. White light streamed down onto and around him, giving the illusion of a classical statue carved in marble. He was the most beautiful thing she had ever seen, and at that moment she wanted him with all her heart. Wanted him with such intensity that her whole being throbbed and pulsated with the rhythms of the night. Wanted him and knew she could not have him.

Ever. As soon as she felt her desire rising up like warm smoke, she heard again the words he had uttered to her last night. Ye ain’t content jist to look. Ye have a greedy soul. Ye have to have it. She recognized the truth in them. She was a greedy soul, wanting everything she found beautiful and good, and her greed and her pride had already caused him sorrow. She watched him needfully until he lowered his gaze to the far darkness, and then took one step forward and plunged like an arrow into the water. Noiselessly she fled back to the cabin.

Shortly afterward he returned, cheerful and damp. She watched him sorrowfully, wondering if there was a way she could love him without hurting him and herself. How could she have him and all the other things that she had yearned for all of her life? She felt half mad, trying to work out a plan that made sense. But it always came back to Impossible. Impossible. Impossible, pounding in her head.

“Wanna play checkers??”

“No. I—I think I’d like to read.”

“All right. I got poetry mostly. And philosophy. I don’t go in much fer fiction.” He perused the shelves, looking for something suitable.

“On second thought, Howard, I think I’ll just go to bed. I feel pretty worn out.” She looked around restlessly.

“Sure.” Let me make ye up some bay leaf and chamomile tea. Hit’ll help ye sleep.”

She watched him work, speaking sternly to herself, angry at the way she had felt the lust for him rise up hot and sweet. She remembered the way he had tasted the night she had kissed his mouth; it had been soft and desirable. Shivering with the recollection, she shook herself again. She was terrible. She did not know why she should be feeling so out of control.

Lying tensely in the bed, she listened while Howard strummed his guitar and sang softly. His voice, too, was warm and honeyed as he sang an old ballad she recognized:

In the clover, where I found my love

And I lay tangled in her hair

In the clover where we cooed like doves

And I kissed her lips like cherries fair.

In the clover, in the clover,

Our hands entwined with sweet flower chains.

But winter winds blew the blossoms away

And she left me full of sorrow and pains

When Spring comes again I’ll sing my song

Of love so sweet and true

And I’ll wait in the clover, it won’t be long

Till our love returns, then I’ll marry you.

She thought of fields of clover lying green and white in a high mountain meadow. Clover and mint. Fields of mint. She drifted off to sleep somewhere in a field of mint.

When the morning came, Geneva felt wonderful, cleansed of body and soul. Her feelings toward Howard had dissipated during the night, so that she was able to see him as merely a friend again, a good friend. One with whom she could entrust her life. One who had entrusted his most important secrets to her.

“Ye want to leave right after we eat, or wait till afternoon?” he asked. If ye don’t think ye’ll be too wore out later on, I’d like to show ye around. There’s caves up above us with ancient paintin’s. Nobody knows about ‘em but me, but I reckon I’ve already shown ye my biggest secret awready, so there’s no need to hide the rest.”

“Oh, Howard,” she breathed. “I’d love to see cave paintings. I’m in no rush to get back. We can leave as late as you like.”

Immediately after breakfast, they struck off through the forest, and after a half hour of walking, Howard guided her up a rocky draw choked with impossibly close underbrush. At the top they came to a creek, which widened as they followed it upstream. When they reached a low place where the water was very wide, still, and shallow, Howard instructed Geneva to take off her shoes and socks. “It’s straight across here,” he said.

Searching, she could see nothing but a sheer rock face on the opposite bank. “Where? I don’t see anything.”

“There”, he pointed, leaning his head close to hers so they would have the same vantage. As his shoulder brushed her cheek, she felt it again—that sudden, sweet jolt that shook her senses and made her tremble. She took a step away from him.

“I don’t see a thing,” she said brusquely. “Let’s just get over there.”

They waded carefully across the stream, treacherous with uneven, moss-slippery rocks. Howard reached for her arm, but she waved him away, laughing brightly, afraid for him to touch her. Once across, he pointed above their heads and to the right. “Up there.”

“In that little narrow slit? Nobody could squeeze in there.”

“Hit’s bigger’n it looks. Here, yew go first. There’s enough toe holds to git ye up all right. Jist be careful.”

Glad that she was not afraid of heights, Geneva threaded her way up ten feet of the cliff to the small fissure in the rock. As he had promised, it was barely large enough for a man to squeeze into. She stood at the opening, waiting for him to come up behind her with the flashlight.

“Watch it right here. There’s a little lip jist in the entrance, then it levels out and widens. Jist step careful.” He eased his shoulder through the fissure, then his head and the rest of his body disappeared. She followed immediately, treading carefully behind him until the cave widened out enough for the two of them to stand side by side.

“Hit’s not far back,” he whispered solemnly, as if they were in some sacred place. “Straight ahead.” He gave her a tiny push, walking beside her with his hand on her back until they made their way through a natural arch that opened into a small room. At the threshold Geneva stopped, uttering a small cry. Howard’s flashlight beam had fallen upon a stunning array of beautiful and intricate paintings, still brilliant and perfectly preserved. There were several scenes ranging from the most simple depictions of warriors hunting strange beasts to large, meticulously drawn patterns that held cryptic meanings indecipherable to Geneva.

“Beautiful, beautiful,” she breathed. “Howard, this is a real treasure! How did you find it?”

“I found it years ago, after I came back from Oklahoma. I liked to wander around the mountains, and I found it one day when I was tryin’ to scale the cliff. The man who owned it had never seen it, and one day, I saw him out in his field and I tole ‘im about it. This land had been in his family for over a hundred years, and none of ‘em had ever seen it as far as he knew. After that, we spent a lotta time together, searchin’ for more caves. He wuz sorta like a second father to me. He did the things fathers usually did with their sons, while mine couldn’t. He wuz a good man.”

“Did he leave it to you?”

“Yes. He had no younguns, no family at all, so he left me all his land when he died. The land where the mine is wuz his. He wuz a good man,” he repeated.

They explored the cave for another hour. Geneva found it hard not to touch the delicate paint, but she kept her hands to herself and peered at each picture closely under the light.

“I think this one represents a marriage,” he commented, pointing to one of the more elaborate drawings. “See, here’s a woman, dressed finer’n anyone else, and over here is a man, the only one wearing feathers.” He moved the light downward. “This looks like the priest or the medicine man, maybe the chief. He looks like he’d perform the ceremony. And all the people—see the streamin’ lines comin’ from ‘em? I think that must be good wishes.”

He moved closer and pointed again. “And look. See here, floatin’ between ‘em, looks like an unborn baby, curled up like it would be in the womb. It’s like it’s waitin’ to come to ‘em.”

“It’s marvelous.” She could not believe she was seeing these pictures, perhaps thousands of years old, painted by people so long dead that even their language was forgotten. And yet their art was more sophisticated than European art of only a few centuries ago. How remarkable was this day! “Thank you for showing me this. You know I won’t tell,” she said reverently.

“I know, Geneva. Now we should go on back. We’ll have us some dinner, then ride on back down. Yew feel all right?”

“I feel wonderful, thank you. Can I come back here some day?”

“Yer always welcome.” She could not see his face, but his voice resonated low and husky and held the darkness of a sultry summer night. She caught her breath and felt the flush rise in her face once again. Hesitating, she looked down at the circle of light on the sandy floor of the cave, afraid to lift her eyes, afraid to move. If he could know how she trembled when his hand brushed her arm! She did not know what she would do if he touched her; she feared that he would read her thoughts—that she would leap into his arms and press her mouth against his. Without realizing it, she willed him to touch her. She closed her eyes and lifted her face, leaning toward him until she swayed.

“Are you comin’?” he asked.

“What?” She opened her eyes. He was standing at the cave entrance.

“Do ye want to stay and look some more? Don’t ye think we oughtta git back?”

“Oh. Yes. We need to get back.” She brushed past him into the brilliant sunlight.

They hurried back to the cabin, speaking little, just concentrating on the rocky trail until they were in sight of the familiar forest. Several times he reached out as if to touch her or steady her, but he always dropped his hand before he made contact. When the trail grew easier, they walked separately, talking about the domestic issues of lunch and horses and how they would simply forget to tell anyone about the days they had spent there. Geneva was especially mindful of the secrets she held.

The sky turned blue and the day grew hot. When they reached the place where the mine lay, Geneva stopped to bathe her face and feet in the rocky stream. Howard settled on a nearby rock and looked into the deep woods. His eyes grew brooding, as if he had moved his soul away into a distant place. Out of the corner of her eye, Geneva watched him, wondering what kind of man he was. He seemed so simple, as if there was nothing more to him than what he presented, and yet, she was growing more and more aware that there might be depths of him that would never be plumbed. She turned to the running water and cupped her hand to drink.

“Ye better not drink that water,” cautioned Howard. Hit’s too far from the source.

“Oh, I’m not afraid of a little E coli. I’ve drunk plenty of water from running streams, and it’s never hurt me before. We’re not downstream from anything that looks dangerous to me.”

“There’s wild boar in these parts, and they carry parasites that’ll make ye real sick. Yew think ye had fever the other day, it’ll take more’n boneset ta git ye over Weil’s disease. Come on,” he said, sliding off the rock. “There’s a spring over yonder. We’ll slip on over there and git us a good drink.”

Dutifully, she followed him into the dappled shade where he brushed through the ferns and led her to a small spring bubbling from a tumble of mossy rocks. The amount of water streaming over the moss was too small for her to capture a drink with her hand, so she held back her hair and laid her cheek into the velvet. The water was cold and pure. When she lifted her streaming face, he chuckled and leaned forward.

“I usually pick out the critters afore I drink, unless I’m real hungry,” he said, reaching into the moss where she had just put her face and pulling out a snail and a few small beetles. “But I reckon hit’s jist as easy to strain ‘em out with yer teeth.”

Geneva laughed. “I am hungry. Wish I had known they were there. I’m in the mood for escargot.” She bent and drank again, feeling reckless and a little like a wild creature herself, and she thought about how nice it would be to take off all her clothes and loll around in that deep moss. She plucked a long fern frond and tied her hair back with it, then preened a little while he bent to drink. She felt lightness suffuse her being.

The sky was still blue when they returned to the cabin, but as they sat down to lunch, it darkened deep and threatening. A thunderstorm rolled in from the west.

They looked at each other. “It may let up,” he offered.

“You think?”

He grimaced slightly. “I don’t know. May. May not. We’ll jist wait it out.”

They waited until nearly dinnertime, then, watching the dark rain beat hard upon the earth, Geneva sighed and commented, “Well, we can stay one more night. Is this Thursday?”

“Friday. When will yer sister be home?

“Tomorrow night or the next day.” She paused, dreading the growing silences between them and what those silences held. She wondered if he could feel her thoughts when she looked at him. Surely he did. They throbbed nearly palpably to her. She was careful to keep her eyes averted. “We can wait. We’ll go first thing in the morning.”

They ate an early supper by firelight, then Howard lit the lantern and they washed dishes and settled down to cards. They had played two hands of gin rummy when the rain stopped and watery sunlight lit up the windows. Howard moved to the door.

“It’s over. Blue sky jist ahead. Yew want to go fer it tonight?”

She joined him at the threshold. The sun had already dipped below the tree line. “No. It will be dark soon. I don’t want to chance it.” She said it slowly, fearfully. Something bid her to stay. She shivered.

“Yer right. Won’t be long.” There was a silence; he broke it by asking cheerfully, “Wanna make a pie?”

They gathered huckleberries in the dying light, then Geneva mixed flour, water, shortening, and sugar together while Howard put the huckleberries and water in the pan and set it on the fire. As soon as the juice was bubbling, they dropped the batter by spoonfuls into the boiling berries.

They ate it outside on the porch steps. Already the sky was deepening, and a handful of stars began pricking their way through the dark blue.

“Yew want another hot bath? Plenty of rainwater.”

“Can’t pass that up. You going for a swim?”

He shrugged, smiling, “Might as well.”

He built the fire outside once again, and she helped him set the zinc tub on rocks above it. Then they dipped water from the rain barrel into the tub and waited for it to simmer. Howard mixed up another batch of soaproot and laurel. This time he spiced it with honeysuckle.

She put the concoction to her nose. “It’s lovely,” she said, smiling, waiting for him to leave.

Her smile met his eyes. He was looking at her with a quiet intensity that made her heart thump. Almost imperceptibly, he tensed. She saw his jaw go taut in the lampshine streaming from the window, and she was glad that she stood in darkness, for she knew he would surely see the quick rise and fall of her breast. She fought to keep her breath steady.

“Bet I get cleaner’n you do,” she said lightly.

He relaxed. “Yew kin try. Enjoy yerself.” He disappeared in the darkness.

She climbed into the tub, shaking. She washed her hair and her underwear once again, and scrubbed her clothes before she put on the long flannel shirt and brushed her teeth with mint and sweet gum. Restlessly, she hung her clothes on the porch rail and sat down on the steps, her breath unsteady, and waited for Howard.

The darkness sang its caressing songs, and once again the whippoorwill called to her out of the night woods. She thought of Howard standing on the high cliff, facing the moon, dropping into the water so fearlessly. Her heart rose in her throat, and she found it impossible to rid herself of the image in her mind. She wanted to see him again. The thought burned her brain, and before she made herself think of how wrong this could be, she was making her way toward the creek and the smell of peppermint.

She arrived in time to see him climbing up the rock and poising his face to drink in the moonlight. Back and neck arched, he looked like a proud stallion sniffing the wind. Then, just like the night before, he stepped into empty air and dropped straight to the water. She heard the splash and told herself to run, but she wanted to see him so beautiful just one more time. She willed her feet to move; they refused. Her eyes searched the boulders, her ears strained for the sound of splashing, but she could hear and see nothing except darkness and the voices of the night until he rose out of the water and stood before her.

He loomed up large, dark, and silent. Water ran in dark little rivers down his face and body. She thought if she could not touch him, she would suffocate. Very slowly, with a shaking hand, she reached up and delicately traced the line of his collarbone. Water ran over her hand and dripped to the elbow. She wanted her whole hand to caress the wetness, but she stopped, terrified by both his presence and her feelings.

He stood perfectly still while she touched him, but before she dropped her hand, he caught it in his own, and very slowly, as easy as breathing, he brought it to his lips and kissed the knuckles. His chest convulsed. The trembling spread from her hand to every nerve in her body. Looking at her hand as if it were a rare and delicate creature, he kissed her palm and then gently bit the heel of her hand. He kissed her wrist, nuzzling it softly before he leaned close and brushed her forehead with his lips. Somehow, she was in his arms, and their mouths collided.

Geneva had often read about passionate kisses, and she even thought she had experienced a few of them. But this kiss was unlike anything she had ever known. She had heard about the earth moving, had thought it was a metaphor. This kiss enlightened her. The earth not only moved, it danced and leaped. She lost her balance and leaned hard against him to stay upright. Small explosions in her brain and in her loins spiraled upward and outward so that she found herself expanding into something large and luminous, like a sunflower blossoming.

This must be what they call Chemistry, she thought, then her brain simply quit. She became nothing but feeling.

Howard broke from the kiss and ran his hands over her back and shoulders. Then, seizing her shirt at the collar, he ripped it asunder with one smooth movement. Buttons dropped into the mint at their feet. His hands and his lips pressed hot like a brand upon her, and she reveled in the heat in them, the heat in her own flesh. Again came the explosions, the blossoming. She was in a boiling river, being swept away; she was tumbling over and over in water and fire and drowning passion. Gasping, she pulled him down onto the minty leaves where she touched him worshipfully. He tried to speak. “Oh, God. I feel like I’m in an avalanche,” he choked out. Her kiss silenced him, and they spoke no more.

Later they picked themselves up and made their way back to the cabin where they slept curled up tightly together until midnight when a caressing hand on her forehead awakened her.

“Wake up,” he said gently. “I want to show ye somethin’.”

She reached for him, wanting his kisses, but he slipped from the bed, stripping it of the blankets and throwing them around her shoulders. “Better put yer shoes on. It’s a little ways.”

Hurriedly, anticipating yet another wonder, she slipped into her shoes, then reached for his hand so he could lead her outside into the redolent, velvet darkness.

“Where are we going?”

“Jist up ahead.” He pressed her hand and tugged her gently along until they came to a clearing where the ground was a smooth expanse of exposed granite. There he spread the blankets upon the rock and lay flat on his back. “Come on,” he invited. “Lay down here.”

She curled up beside him and put her arms around him, but he pointed upward. “Look, there’s one now.”

She followed his pointing finger and found herself looking at the burning trail of a shooting star. Another one shot off an angle to the first. And then another and another streamed across the sky before her delighted eyes.

“Oh! A meteor shower! Oh! and it’s such a clear, beautiful night! How did you know?”

He chuckled. “Yew’ve lived in a house too long, darlin’. I bet yew don’t even know what this is.”

She giggled. She felt full of little bubbles of happiness. “It’s not a meteor shower?”

“No. It’s the tears of Singing Eyes.”

“Who?”

“Singing Eyes. A Cherokee maiden who lost her lover and then threw herself off the edge of the world.” He swept his hand toward the sky, alive with falling stars. “These are her tears, and she’s cried ‘em ever year since the earth was new.”

“Tell me the story.” She snuggled closer to him and pulled the edge of the blanket over herself tightly.

“There wuz two lovers from neighborin’ villages, and their fathers had once been close friends, blood brothers, but for many years they were enemies. One of ‘em had gone away over the mountains and had come back with a bride he had captured. She was so beautiful that his friend fell in love with her and wanted her so bad he could think of nothin’ else. He found out that she was unhappy with her husband because he had stolen her away from her family and that she often cried at night because she wanted to go back to her people.

“So one day, the friend came and stole her, and she went with him because he promised her to go live with her and her people if she would be his wife. They made the long journey, but when they got there, they found out that her family and most of her people had been killed by an earthquake, and the rest had gone to live with a neighboring tribe. Since there was nobody left that the woman loved, she agreed to go back home with the man and live with him and take his family for her own.

“When they got back, her husband was real mad, and he swore that he would forever be enemies with his former brother, and from then on they never spoke or came to see one another.

“Years passed, and both of ‘em had children. The man who had lost his bride to his friend married another woman and they had a daughter who had eyes so beautiful and lively they named her Singing Eyes. The other had a son, his name was Smoke on the Mountain, and since the two families never visited, the children never met.

“But one day, Smoke on the Mountain, grown into a young man, wuz huntin’ and came across Singing Eyes as she was washin’ her hair in the river. They fell in love and wanted to marry, but when her father found out, he swore he’d kill Smoke on the Mountain if he came near Singing Eyes again. So they met deep in the forest, where they planned to run away over the mountain together. Her father followed them with all his kin, and they chased ‘em to the edge of the world. One of the men shot an arrow into the heart of Smoke on the Mountain, and Singing Eyes went mad with sorrow, and she threw herself off the cliff.

“She was much loved by her father, and he was so hurt and shamed by what he had done that he asked the spirits to help him find a way to protect other young lovers from the hate of their fathers. The spirits heard him and felt so sorry fer ‘im that they turned her tears into fallin’ stars, so they could be a reminder to fathers to listen to the hearts of their children.”

“That’s a very sad story.”

“It’s a very old one. There’s a dance about it. I learned it when I was a boy. It is a dance that the braves of my mother’s tribe dance on this night when they want to declare their love to a particular woman, ‘specially if he’s afeared her father might not approve of him, or if he feels he’s not worthy of her. It’s both a love song and dance and a sort of pleading for acceptance.

“Do you remember it?”

“Yes, and the song, too. My father, ye know, is white. He learned it to dance fer my mother, ‘cause he knew if she married him he’d be takin’ her away from the place she knew and loved. When I was little, he always danced it agin’ fer her on the nights it rained stars.”

Geneva felt a moment of anxious possessiveness. “Did you dance it for your wives?”

He did not move, but she felt him withdraw for a moment. When he spoke, his voice was soft. “No. With Sarah Grace, there wasn’t no need. We were young, and so in love, we felt we were already one person, there was nothing that could separate us. And things moved so fast with Aster, I never got the chance.”

Geneva was afraid to ask, but her need was great. “Would you show it to me?”

There was a long silence while Geneva and Howard turned their gaze toward the heavens raining white fire, then all at once, as if he had suddenly made up his mind, Howard rose, and lifting his arms toward the sky, began to sing softly. Geneva could not comprehend the words, but she felt the power of his feeling, and she watched with stilled breath as he began to move, slowly at first, then more rapidly until he at last was leaping and spinning around her. Sometimes his eyes held hers for long moments before he broke away and turned to sing to the heavens again, and sometimes he approached her with his eyes lowered, as if he feared or revered her. But always, there was a sense of overwhelming passion, mingled with hope and fear as he approached and fled and danced his mysterious dance around her.

She sat very still, comprehending nothing but the passion in Howard’s voice and in his lithe, naked body as he wove among the falling stars. He was so beautiful she could have spent her life just watching him move so sensuously, and then, she felt compelled to stand, to feel herself closer to the stars and to feel the rhythm of his song. Slowly she rose, cold from the damp night, but she flung off the blankets and let the pulse of the sky and the song and the earth fill her until she felt herself grow warm and light, as if she had become part of the music, or as if she had become the chorus to give fullness to Howard’s feeling. Breathlessly, she watched him and listened until at last, his voice rising to a painful wail, then softening to a note so low it felt like a caress, he stopped.

There was a silence, then he dropped to his knees before her and flung his arms around her thighs, burying his face in her belly. Slowly, he stood, lifting her high into the air. Without meaning to, she flung out her arms to embrace the night sky and lifted her face to watch the stars fly around her head. She was wearing a crown of stars. She was worshipped, she was alive with love and passion and desire and youth. Her flesh became immortal and her spirit sang like a river.

And then the stars stilled themselves, and Howard lowered her slowly and gently until their faces pressed close together. Hungrily, half crazed with desire, she clung to him, and he gave a little cry before his mouth found hers and the stars began to spin again.

They made love until the night grew pale and the meadowlark sang, then Howard pulled the blankets tightly around her and pulled her close with her face nestled in the hollow of his shoulder.

“Hit’s gittin’ on toward mornin’,” he murmured.

“Hmm,” she replied sleepily. “It’s too cold to get up.”

“You okay on this rock?”

“What rock?” I feel like I’m in a featherbed.”

He chuckled. “They’s critters out here could eat us. We’d better git on back.”

She ignored him. “Howard?”

“Yeah?”

“I just realized, I don’t really know who you are. I love what I know of you, but I’ve never known anyone like you. You seem to know all about me, but every time I think about you, I see so many different people, so many sides to you. I mean, you seem to belong to these hills, but you read philosophy and you know all about things, nature and literature, and cars and horses.” She stopped, wondering if she could ever find his definition.

“My grandfather gave me the Cherokee name I carry. ‘Anigia Hawinaditlv Tali Hilvsgielohi.’ Hit means ‘One Who Walks in Two Worlds.’ I think at the time, he meant it to mean that I wuz both white and Cherokee, but now I think it fits in more ways than that.”

Startled, she sat up. “That should be my name! I mean, I’ve felt it all my life. I want to be in so many places at once. Anigia—How do you say it?”

He repeated it slowly,” Anigia Hawinaditlv Tali Hilvsgielohi.”

“Well, I can’t say it, but that is me, too.”

He tugged at her until she lay beside him again.

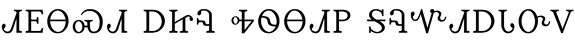

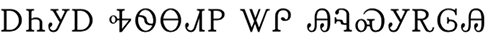

“No, your Cherokee name is ‘Digvnasdi Atsilv Hawinaditlv Galvquodiadanvdo,’ I’d say, ‘One Who Strikes Fire In the Soul.’ Fer me, that’s your name.”

She did not know how to answer. As far as she was concerned, that should be his name. Maybe they weren’t so far apart in the things that really mattered. It seemed to her now that all the differences between them were merely superficialities, inconsequential little details. She stroked his smooth chest. “You strike fire in my soul.”

He grew playful. “Well, hit’s a good thing we got all this fire agoin’, else we’d freeze to death out here. Maybe we kin git on back and put somma this fire onto some kindlin’. I don’t want ye gittin’ chilled again.”

Reluctantly, she rose, and before she could begin shivering, he wrapped the blankets around her again. Together they walked back to the cabin where they slept as lovers, clinging to one another, even in the profoundest of sleep, dreaming of the other’s touch and the rhythm of bodies, souls and spirits in perfect harmony. Deep into the morning they slept to the sound of all nature awakening and shouting their joy to the heavens.

When she woke, the sun was quite high. Before her eyes had opened and consciousness had come to light in her brain, her heart was singing. Something wonderful had happened to her in the night. She opened her eyes, smiling.

Howard, still naked, still beautiful, crouched before the fire. When he heard her move, he turned his face upon her and his eyes lit up with love. Geneva had never seen such happiness in anyone’s face. He radiated joy so that his countenance was nearly unrecognizable as the man with whom she had spent these—how many?— days and nights.

He sprang to the bed and knelt, kissing her eyes and her face and stroking the arm that lay outside the blankets.

“Morning,” she drawled, touching his face. She knew she was in love. There was no thinking about it or planning or even considering what it might mean. She was simply a river of happiness, flowing ceaselessly toward her beloved.

“Morning, darlin’.”

“Go for a swim with me?”

He shook his head. “Breakfast is goin’. Besides,” he added, lifting his arm to his face and inhaling deeply, “I don’t want to wash the smell of you off me. Mmmm,” he closed his eyes. “Geneva with mint. Makes my mouth water.”

Happily, she sprang from the bed. “What’s for breakfast?”

“Oatmeal and hoecake. Lord, woman, you make a man hungry. I cain’t wait fer breakfast,” and he dived for her and buried his face in her neck, making gobbling sounds until she shrieked with laughter and wrapped her arms around him.

She was happy, more than happy. She belonged here and to this man who made her feel so complete. Languidly, she breathed his scent, then suddenly pulled away and asked, “What was that you called me last night? Strikes Fire in the Soul? No, that’s not right. That is your name. I’m that other one—Walks in Two Worlds. But not anymore! I just want to walk with you! You’re the fire-starter!”

“Oh, no,” he chided. “Ye cain’t take a man’s name away from him, and ye cain’t step out of yer own name. Ye’ll have to wear it the rest of yer life, now that it’s yers.”

“Okay, so tell me how you pronounce it, so I can come when you call me.”

He crossed to the bookshelf and retrieved a notebook. “Here,” he said, taking up a pencil. “Here’s you, how it looks in Cherokee,” and he wrote:

“Digvnasdi Atsilv Hawinaditlv Galvquodiadanvdo. Easy enough.”

“For you, maybe. It’s impossible for me!”

“And here’s how my name looks,” he continued, writing beneath the first:

“Anigia hawinaditlv tali hilvsgielohi.”

“And this is us together,” she said, taking the pencil from him and encircling the two words in a heart. “But teach me how to say it. I want to know you, in every way. Anigia… hawin.…”

“Anigia Hawinaditlv Tali Hilvsgeilohi. How about we shorten it to just Ta li—two? Call me that, and I promise I’ll come arunnin’!”

“Ta li. I can handle that. Ok, now I’m off to my beauty bath. I have mud all over me.” She kissed him lightly and scampered off to the creek.

She plunged into the water and swam around the large rock pool until she felt she had used enough energy to be able to contain the life surging through her. She stood for a moment beside the mint bed to let the water run and drip down her naked skin, smiling at the crushed and hollowed out place in the shape of their loving bodies. Then, lightly she ran back to the porch and snatched up her nearly dry panties off the rail. A sudden wave of happiness swarmed over her, and she could not help but execute a neat little pirouette and glissade as she held up her panties to determine which side was the front.

She did not make that determination.

As she looked up, her vision was pulled beyond the elastic of her panties, beyond the porch rail and the steps and the zinc tub where she had bathed. Beyond it all, right to the ashen face of Howard Whittaker Graves, III.

She blinked, certain that he was an apparition, but when she refocused, he was still there, and behind him stood Jimmy Lee, Lilly, and Sally Beth, all open-mouthed and still as stones. Beside Jimmy Lee stood Lamentations, whining and looking anxiously at his master.

For a second Geneva stood in horrified disbelief, staring at the small crowd clustered at the edge of the forest, then slowly she lowered her panties and let her eye rove until she focused on Sally Beth’s hot pink toenails peeking out of open toed, jeweled sandals. The reality of her situation suddenly hit her, and she turned and fled into the cabin, slamming the door behind her.

Howard was dressed, thank God! and setting the table for breakfast. He looked up to smile at her when he heard the door, but when he saw her face, the blood drained from his own.

“Oh, God! What have I done?” cried Geneva in a frenzied whisper. “Oh God! What will I do?” She grabbed a blanket from the bed and fled through the back door, heading for the deepest thicket she could find to hide from the source of her shame and dread. Howard Graves! How did he find her? What would he think of her here with Howard Knight! He would find out what they had done last night! He would laugh with such derision! And Sally Beth and Lilly! They would tell everyone! Oh God! How could she have been such a fool? Howard Knight, of all people! No one would ever understand. She wrapped herself tightly in the blanket, rocking herself and wishing the earth would swallow her up. Death would be preferable to this humiliation. Then the hot tears came, and she dashed them away angrily. She did not deserve the luxury of tears! She would merely sit there and suffer until everyone disappeared. Then she could rise and make her way back down the mountain, and then perhaps to parts unknown to her, and more importantly, where she would be unknown to others.

She steeled herself to hide forever, but before many moments had passed, she shifted uncomfortably. The blanket was becoming too warm, and time seemed to be ticking its way by too tediously. How long would she have to sit there before she finally figured out a practical thing to do? Reason began to hint that the mess would not just disappear.

She heard her name. Sally Beth was approaching her hiding place. “Geneva? Geneva honey? Yew can come on out now. Howard explained everthing. We all know it looked a whole lot worse than it really is. Come on out now. I’ve got yer clothes.”

Geneva’s grateful ears pricked toward her cousin’s voice. Had she said Howard had made it sound not so bad? Tentatively, she raised her head and called out, “Here I am. Sally Beth. Over here. Bring me my clothes.”

Sally Beth approached her cautiously. “Goodness, you gave us such a start! Here we were expectin’ to maybe find yew dead, and then Boom! There yew are, buck nekked, holding up your panties like yew had all the time in the world to step into them. I liked to have died! Your mama would skin yew alive if she could have seen yew! It’s a good thing Howard told us all about it, or I bet Howard—yew know, the other one, yer boyfriend—would really be mad!

“I mean, he was mad! Fit to be tied! But he feels real bad now, since he found out how sick yew’ve been and all. He wants to see yew as soon’s yew get dressed.”

“He’s not mad?” asked Geneva incredulously.

“Gracious no! I mean, we had no idea yew were sick! Howard just thought Howard—Knight—had kidnapped yew or something! He pitched a fit all the way up here!”

“What did Howard—Knight—tell you?” ventured Geneva cautiously.

“Oh! He told us how yew’d had a high fever for days! How yew nearly died! And that yew’ve been out of yer head for these three or four days, so that he was afraid to leave yew and go get help. Oh, Geneva! It must have been jist awful! And yew do look jist terrible! You’re just as white, and I can see yew’ve been feeling too bad to even comb yer hair! Yew look like a haint!”

Geneva’s hand instinctively went to her tresses. “Do I really look that bad, Sally Beth?” she asked miserably.

“Oh, Lord yes! Yew look like yew’ve been wallerin’ around in the bed for days! I mean, yew must have been in terrible shape not to even be able to comb yer hair! Now, here’s your clothes, honey. Get on in them and we’ll just go on back and I’ll fix yew up real pretty so yew can face Howard. My goodness, Lilly’s still tryin’ to take him away from yew! Yew should have seen her comin’ up here. All over him, she was! I jist hate how she can act like such a tramp sometimes. I mean, really! Trying to take a sick girl’s boyfriend away from her while she’s practically on her deathbed!”

Sally Beth chattered on thus while Geneva dressed with trembling hands. When she had finished, she made an attempt to pull some of the tangles out of her hair.

“Oh, just leave it. I’ll fix it for yew when we get back. How yew feeling? Yew think yew can make it back down the mountain? It was just awful coming up here. It took us since six o’clock this mornin’ to walk up here, and look, it’s nearly eleven now! And we’ve been up all night! Howard was about to have the FBI out after yew after Jimmy Lee came by the house and told him Howard Knight’s daddy had said the last he saw yew, yew and Howard had left on horseback together. And then we went up to Howard’s place—that’s a pretty little place, isn’t it? And the horses were still gone! And your pocketbook sitting on the kitchen table! If Jimmy Lee hadn’t agreed to help us look for yew, why Howard was going to call in the FBI! He said so!”

“Oh, no!” moaned Geneva. She could imagine the place swarming with search parties. “But why are you here? And Lilly?”

“Oh, we had come by the house last night to see the babies, and we saw that cute little car of Howard’s there, and he was sittin’ on the porch, just as pretty as yew please, and nobody home, so of course, Lilly, being the little hussy that she is, just had to sit there and talk to him for an hour! Anyway, along comes Jimmy Lee? She lowered her voice confidentially, “Geneva, I think yew may have a problem with Jimmy Lee. He was real surprised to find out that Howard was your boyfriend, and do yew know, he had come to court yew! Can yew imagine! His exact words! Court yew!

“Anyway, Howard asked him where yew could be and he said he didn’t know, he had come by every day and every night to court yew since Wednesday, and yew hadn’t been home at all! But he said he went up to his grammaw’s house yesterday? And Howard’s daddy—Howard Knight, that is—had told him he had seen yew take off on horseback with Howard on Wednesday afternoon, and he hadn’t seen Howard since!

“So then, Howard—Graves—I declare, honey, this is gettin’ confusing! He gets all mad and wants to take out after Howard and yew, and he threatens to call the FBI and get a search party—I told yew that part already—and Jimmy Lee got real nervous and said he thought he knew where yew might be.

“Well! By this time Howard’s so worked up, he’s about to pop something, and Lilly’s acting all sweet and syrupy and says she’ll go with them, and I jist decide to go along to keep an eye on her. I mean, mamma would die if she knew she went traipsing out all over the country with two men! And then she gets right in that little sports car with Howard, and I have to ride in Jimmy Lee’s truck that has a hole in the floorboard! Yew get sick if yew look down! Yew can see the road running right under yew!

“Well, then we got to Howard’s house about four in the morning, and of course yew aren’t there, and the horses are gone, and Jimmy Lee tells Howard he’ll take him to where yew might be if he’ll promise not to call the FBI.” She assumed the confidential whisper again. “Geneva, I think Jimmy Lee’s got a still around here someplace. He was as nervous as a cat about comin’ up here!”

“Anyhow, we take off walkin’, and I had no idea we’d be this long in getting here! Seems like we just wandered around for hours, circling around and switching back, until Howard starts to act suspicious, and then we just came up to a clearing, and there yew were, not a stitch on, dancin’ with your panties!” She giggled. “It was so funny! Yew coulda been standin’ in your own bedroom, yew jist looked right at home, pickin’ out your pretty pink panties with the little lace flowers on them!”

“Okay,” snapped Geneva. “I get the picture. I’m ready to go back.”

“Oh, great! But I don’t know how in the world we’re going to make it back with yew sick and all, and I’m so tired I could just lay down and die right here!”

Sally Beth did not look tired in the least. She looked like she had just walked away from the cosmetics counter at Belks. Her fine, fluffy hair was perfectly arranged into a towering pouf, and her eyes were as bright as a child’s. And how had she walked for five hours up a mountain in those minuscule, jeweled sandals? Her feet were even clean!

“I don’t feel sick anymore, Sally Beth. Howard’s been treating me with medicinal herbs, and I think I’m well enough to get home. We have the horses here.”

They took a long time to get back to the cabin. Geneva willed herself to take each step. Howard had done what he could to protect her reputation; now the rest was up to her. She said a silent thank you to him as she opened the cabin door.

They all stared at her, all but Howard Knight, who busied himself at the fire and did not even turn his head as she entered the room. “Geneva!” cried Howard Graves at last. “I’ve been worried sick about you. How are you feeling? Goodness, you’re so pale. Howard here told us how sick you’ve been. Sit down.”

She sat carefully, keeping her eyes down.

“I’m so sorry we surprised you like that. Howard said you’d been begging for a bath but this was the first morning he’d let you go down to the creek since your illness.”

She glanced at Howard Knight. He was concentrating very hard on something in the pan over the fire. The joy she had seen in his face an hour ago had vanished. He looked pale and haggard, and when at last his eyes glanced up and met hers, they were full of grief.

Suddenly, she did not care what anybody thought. She only cared that she was in love and that her lover was in pain. She wanted to run to him and embrace him and see the joy suffuse him again. She remembered the passion from the night before, and nearly cried out in her anguish. She still wanted him! She didn’t care who he was or where he lived. No one had ever made her feel like she had felt in his arms last night. Never had she transcended herself, had moved into a sphere where she had stopped thinking and calculating and just let herself be carried along, as if she were riding on flaming horses. Nothing but feeling for him, nothing but happiness and fulfillment flooded her heart when she looked at him. She would tell them all the truth now, and she would stay here with Howard forever. It was enough to know that she loved him and that he loved her.

She looked at the expectant faces. “Everybody, it’s true that I’ve been very sick. And Howard here has taken care of me, but I want you to know that last night…”

Howard Knight’s voice broke in. “Miss Geneva, I think it’s time for another cup of willer bark tea. We don’t want yer fever comin’ back, now. And since you’ll be goin’ back today, I’d like ta give ye some herbs ta take with ye. They’re out back. Come on, and I’ll explain how ta brew em up.” He addressed the others. “Yew all go on and eat. I know yer about starved to death, and there ain’t enough room around the table for all of us. Miss Geneva and I’ve been mincin’ since early this mornin’ and we ain’t hungry right now. Come on, ma’am.” He picked up a cup from the hearth, and taking Geneva’s arm firmly, he ushered her out the back door.

They stood on the back porch facing each other for a long time before he spoke. Geneva did not like what she saw in his face. Such sorrow. She could not bear to see it after the gladness of the morning.

“Howard,” she began, but he placed his fingers on her lips and whispered, “Now hush. They believed me when I told ‘em yew’ve been sick and out of yer head. Let it sit at that.”

“Howard, I love you! I want to stay here with you. I don’t want anything to do with him!”

“Hush. Yes, yes, I know. I know yew love me. Yew loved me last night, and yew love me right this minute, and I can’t tell ye what that means to me. And maybe ye’ll even love me tomorrow, and when I think of that, I find such hope in here.” He put his fist to his chest, then paused, and his face clouded.

“But there’ll come a time when I’ll be nothin’ but an embarrassment to ye. An embarrassment and a regret. I know that. What could yew see in the likes of me? I cain’t hold a candle to ye. I can’t hold yew. Ye’d be miserable, and I can’t live waitin’ fer the day.”

“No!” she protested.

“Yes. Now, yew just go on down that mountain with that feller and yew fergit about me.” His eyes glistened with unspilled tears. “I ain’t sayin’ ye need ta marry him. I’m just saying ye need time ta figure out what ye want. Ye need a chance ta find yer own happiness.”

“Howard, I found it last night. Please.”

“You ain’t been listening to me, darlin’. We’re too different.”

“You mean you don’t want me? You don’t love me?” He was breaking her heart.

He almost smiled. “Geneva, I’ve wanted yew since the minute I first laid eyes on ye. And I’ve laid awake nights lovin’ yew ever since yew chased me around the barn alaughin’ at me. A man kin love a shooting star all day long, but that don’t mean he kin have it. He kin grab onto it maybe, for a minute, and he kin feel its flame aburnin’ him with such sweetness that he can’t think of nothin’ else, but that don’t mean he kin take it to his heart and make it a part of him.”

She fell silent, grieving at his words.

He swallowed hard. “Now, I been thinkin,” he began, and his voice shook. “Ye might could git pregnant, and I know ye don’t want that, complicate things even worse. Ye kin drink this,” he said, indicating the cup filled with a vile-looking liquid, and it’ll stop anything that might be started.” He drew a shaky breath and licked his lips.

Pregnant? Geneva had not even considered the possibility. Last night had taken her so completely unaware, she had been so overcome with her desire that she had not thought of any possible consequences. Not pregnancy, not Howard Graves, not even any tomorrow. She stared at the cup.

“Take it,” he urged. His hands were beginning to shake. “It might make ye a little sick at first, but that’s all. Yew won’t know one way or the other. Yew kin just think there never was no baby.” He saw the pain in her face. “There probly ain’t, anyway,” he added gently.

She lifted her eyes to his. Tears were streaming down, but his face was impassive, unreadable. It looked like water running over a stone. She felt the wetness of her own face as she stared at the cup in his hands, wondering if she might at this moment be carrying Howard’s child. The thought was unbearably sweet, and she felt her heart lift, but when she looked at his face and saw nothing but blank sorrow, she lifted her hands to take the cup. When she touched it, she suddenly felt the weight of a burdened and miserable spirit. Never had she felt so much a sense of sin, the horror of the wrongs she had done to this gentle man and to herself. He still held the cup, then, slowly, as if he were willing himself to die, released it to her. Without a word she lifted it to her lips and drank the bitter death. He watched her drain it, then silently disappeared into the forest.

She was completely alone. So great was her despair that she did not even allow herself the luxury of crying. Tears were for cleansing, and she knew she could never be cleansed of this pain, this guilt which rose up and enveloped her like a slimy black shroud stinking of corruption. She leaned her head against the pillar and felt despair engulf her so completely that her senses finally dulled.

Howard Graves opened the back door.

“Geneva, darling. You look so sick. Come inside and sit down. I’ve never seen you this pale. Please, come inside. I’m worried about you.”

“I’m okay, Howard. Just tired.” She lifted her eyes. “I want to go home now. I can’t stay here any longer.”

“Of course. We’ll leave right away. Could you eat a bite first? We could put you on a horse, and the rest of us can walk. We’ll make it.”

“Yes. Ask Howard if he’ll saddle up for me,” she said wearily. I’ll be fine. But I’m not hungry. Just let me lie down for a while.”

She could see the concern in his face. “Certainly. Let me help you inside.”

She could not lie down. Her body was not ill; only her heart was sick and heavy with grief, and it made her too restless to lie still. Tossing on the herb-scented bed, all she could think about was Howard’s hands on her, and the way they both had been so transformed by joy. The bitter cup and the tears in her lover’s eyes loomed before her. She rose and paced the floor.

“Feeling better?” asked Sally Beth.

“Yes, some.”

“Well, good. Let me fix your hair a little. You’ll feel a whole lot better in a jiffy. Here. I got a brush, and a curling iron, and oh, Lordy, all kinds of things in here.” She rummaged around in a huge purse, pulling out all manner of beauty aids. Geneva looked at them dumbly.

She started to shake her head, no she did not want her hair fixed, but was startled by a sudden explosion and the “thwak!” of splintering wood.

“Hey!” yelled Jimmy Lee. Everyone looked up in time to see several window panes explode. Lilly screamed, looking horrified at her hand, which held only the handle of a cup.

“Oh, hell! Somebody’s ashootin’ at us! Hit th’ floor!” Jimmy Lee shouted. “Git away from the winders! We been ambushed!”

Everyone dived for the floor, everyone except Sally Beth, who simply moved to the center of the room directly behind the big oak front door and sat down on one of the tree-stump stools. She plopped her huge purse in her lap and waited demurely.

There were terrible growling and snapping sounds out on the front porch. Jimmy Lee cursed, then dived for the door, flung it open, and within two seconds had dragged in Lamentations and slammed the door behind him. The dog was snarling and snapping. As soon as Jimmy Lee released him, he resumed what he had obviously been doing out on the front porch: chasing his severed tail with all the frenzy of a maddened beast. Lilly screamed again and huddled beside Howard Graves in the corner of the room. Sally Beth put her fist on her hip and gazed around her, a puzzled expression on her baby doll face.

“What is it?” cried Howard Graves. “What’s going on?”

Jimmy Lee crouched by the front window and peered out. “Don’t rightly know. Somebody’s after us.” He raised his head slightly and shouted through the broken window, “Hey! Hey yew!” He waved his hand in the direction of the roaring dog. “Shut up, Lamentations!”

“Hey yersef!” came a female voice.

“Whatcher want?” called Jimmy Lee

“I wanna kill yew, Jimmy Lee Land!” came the voice. “I’ll teach yew ta be runnin’ around on me!”

There was a silence except for the sounds emitted by the frenzied dog. “Myrtle?” Jimmy Lee said at last. His voice had lost a good bit of its strength.

“I’ll kill ye, yew bastard. Runnin’ around on me, air ye? I tole ye I’d kill ye, and I meant it. I seen ye with them little yeller haired thangs. Yew cain’t git by with that!”

“Lamentations! Quit it! Igod, yew are the dumbest damn dog I ever laid eyes on. Somebody gimme somethin’ ta knock some sense into that animal.” He put his face near the window. “Myrtle!” he shouted. “Did yew foller me up here?”

“Haw. I sure’s hell did. Follered ye since early this mornin’. I seen ye with them hussies. And now I’m gonna kill ye!” The last sentence was punctuated with another blast. The windows were gone, so all anyone heard was several pellets embedding themselves in furniture and walls. Lamentations renewed his effort to destroy his rear end. Already there was fresh blood drenching the stump.

Howard Knight burst in through the back door. “Lord amercy, Jimmy Lee,” he said, his voice full of disgust. “First ye bring three people up here, knowin’ ye ain’t even supposed to talk about this place, and now ye let yerself be followed by that damn woman. Now git on out there and tell her to quit shootin’ at us. Somebody’s likely to git hurt!”

“Chap, I cain’t go out thar now,” whined Jimmy Lee. “Hell, she’s mad enough to kill me. Yew heard her!”

“Jimmy Lee, I’m mad enough ta kill ye. Now yew talk some sense into that woman before I start shootin’ back! Lamentations, shut up! Jimmy Lee. Cain’t yew shut that dog up?”

“I’m acomin in!” came the voice outside.

“No yew ain’t!” shouted Howard Knight. He yanked his rifle from the wall rack and held it loosely. “I got a loaded Winchester right here, and I’m aimin’ it right at this here winder, and I swear I’ll blow yer head off if yew so much as come into the clearin’.” He slapped at Lamentations with a dishcloth. Geneva wished he really would point the gun. This did not look like the time or place to be bluffing.

There was a long silence from outside. Finally Myrtle spoke again. “Awright. I ain’t comin’ in. Jist send that no good somebitch out here and let me blow his balls off. Yew do, and I won’t shoot no more.”

Long pause. Lamentations slowed down. Howard whacked at him halfheartedly a few more times with the towel, then turned to Jimmy Lee. “Well,” he said. “Yew heard her. Git on out there. She’s gonna blow us all to hell if yew don’t.”

Jimmy Lee squirmed. “Aw, Chap. She might really do it. Yew see how mad she is.” His face brightened. “Yew go talk to her.”

Howard’s disgust grew. “She don’t want me, yew idiot! I go out there, it’ll just make her madder. Now quit bein’ a coward and go on out there!”

“Chap, I swear, I never seen her this mad. Last time she got mad at me she liked to have broke me in two. What if she shoots me?”

“She ain’t gonna shoot yew. She just wants ye ta tell her ye love her and ye ain’t been messin’ with anybody else. Now go on!”

Another shotgun blast pelted the cabin. Lamentations took off after his tail again.

“Huh uh,” Jimmy Lee shook his head. “I’ma waitin’ thisun out. Lamentations!”

Sally Beth suddenly stood up. “Well!” she exclaimed. Looks like we’re gonna be here awhile. No need jist sittin’ around. Geneva honey, yew jist come on over here, and I’ll fix yer hair while we’re waitin’.”

This is it, thought Geneva. The most absurd situation I have ever been in in my entire life. I might as well get my hair done. If I get killed, at least I’ll look decent. She sat herself down on Sally Beth’s tree stump.

“How about a nice little French braid? Or I’ve got a curling iron right here in my purse. Oh, my! What did yew wash yer hair in? It smells like mint! Oh, Geneva, yew got knots in here! It’ll take me forever to get all these tangles out!”

“Yew comin’ out, Jimmy Lee?” The voice from outside sounded dangerous.

“Now, honey!” shouted Jimmy Lee. “Yew know I won’t come out long as yer threatenin’ to shoot my balls off. Soon’s yew calm down, I’ll come out and we kin talk peaceable.”

“I ain’t gonna talk peaceable! I am gonna shoot yer balls off. Goddam man. I leave yew fer one minute and yew take off after ever hussy fer miles around. I know all about that woman yew’ve been runnin’ after. And now yew got her up here, and yew expectin’ me not to git mad? Come out here and take what’s comin’ to ye!”

“I think she’s talking about yew, Geneva,” said Sally Beth conspiratorially, working patiently at a troublesome tangle. “Jimmy Lee’s said some pretty nice things about yew. Word’s bound to get out.”

Howard Graves appealed to Howard Knight. “Looks like she could be here for awhile. Any chance we could escape out the back? Did you get the horses ready?”

A shadow of a smile passed across Howard Knight’s sorrowful face. “Yeah. I got ‘im ready. All saddled up. They’re probly halfway back home by now.”

“You mean?”

“Nothin like a shotgun blast to spook a horse. I chased ‘em more’n half a mile, but they meant business.”

“Shit,” said Howard Graves. “Lamentations, shut up!”

“I think a French braid will be best. Yew need a conditioning bad, and I hate to dry it out more by rolling it. These cordless curling irons get a lot hotter than the regular kind. Yew want the braid to go under or over?”

Howard Knight fluttered the towel around Lamentations’ head. The dog slowed, then dropped in his tracks, panting. “Good dog,” he commented absently.

“Over,” decided Geneva.

“Okay. Yew can put on a little makeup while I’m working. Look there in my bag. I think the rose coral lipstick will be best. It will give yew a little glow. And that peachy blush. And yew need eyeliner, bad, girl. Your eyes have jist disappeared!

Lilly joined in. “No, I think eyeliner looks tacky n the woods. Sally Beth, you look all painted up like a Bourbon Street whore. No wonder that woman out there thinks Jimmy Lee’s cheatin’ on her.

“Jimmy Lee? Yew comin out? I kin sit out here till dark, and then I kin come in and git ye. I do, and they won’t be enough left fer chicken feed.”

“Lilly, I do not look like any Bourbon Street whore! Yew don’t even know what a Bourbon Street whore looks like! Yew’ve never even been to Memphis.”

“New Orleans, Sally Beth,” sighed Geneva.

“New Orleans, either.”

“I’ve seen pictures!”

“Yeah? Where?”

“National Geographic.”

“Well, that’s not the same! They probly fixed themselves up nice ‘cause they knew they were getting their picture taken.”

“Jimmy Lee!!!” Myrtle’s voice had risen to a bellow.

Howard Graves shot a naked appeal to Howard Knight. “Isn’t there anything you can do?”

Howard Knight thought for a moment, then sighed. “All right. Jimmy Lee. Yew tell her yer comin’ out, but yew don’t want anybody to get hurt, so she needs to meet ye down by yer house. Change shirts with me, and gimme yer hat. I’ll take off runnin’ out the back, and she’ll think it’s yew, bad as her eyes are, and she’ll probly will take off after me. I kin outrun her, and yew caint, so I’ll jist lead her far enough away so yew all kin git on away. Knowin’ her, she’ll git good and lost. Got that?”

Jimmy Lee nodded.

“And make sure yew keep Lamentations quiet till she gits out of earshot.” He lowered his voice to an inaudible threat. “Stay off the trail. Cut back and confuse the path, ye hear?”

Jimmy Lee nodded again. “I did that comin’ up, too.” Geneva knew they were discussing ways to keep her cousins and Howard Graves from ever finding this place again.

Howard, her Howard, her beloved, had not looked at Geneva since he had entered the room. Now he glanced in her direction. “Geneva’s gonna be hungry. The rest of yew had a good breakfast.” Quickly he gathered up some warm bread, beef jerky, and something from a tin. These he put in a bag, and, eyes downcast, handed it to her. “There’s willer bark in there. About a tablespoon to a cup o’ water. Steep it five minutes. Or yew kin just chew it.”

She did not move, but merely looked at him until he lifted his eyes to hers. His face was a mask, a perfect blank; his eyes looked like dull, black plastic buttons. She searched for the life behind them, desperately, but futilely. Slowly she took the bag from him.

“Now holler at her,” he commanded

Jimmy Lee took a deep breath and hollered. “Myrtle, honey, darlin’! Yew know I love ye! And I aim ta marry with ye!” He looked apologetically at Geneva. “I don’t mean that, Miss Geneva. I’m jist tryin’ ta git her ta stop this shootin’,” he whispered. He turned back to the window. “I’m acomin’ out! But yer a bad shot, and I don’t want nobody in here gittin’ hurt if yew go shootin’ at me! And I don’t want ye shootin’ at me neither! I’m atakin’ off right now, out th’ back, and I’ll meet ye t’home! Y’hear?”

Sally Beth put her hand on her hip and narrowed her eyes at Jimmy Lee. “Shame on yew, Jimmy Lee! No wonder that poor girl is shootin’ at yew. Yew got no business telling lies like that, and then flirtin’ your head off with Geneva. Hold still, Geneva,” she continued without a pause and produced a can of hair spray from her copious bag. “I just need to spray yew.”

Jimmy Lee looked contrite but said nothing.

“Well, I’m gone,” said Howard Knight. “Git out quick as ye kin,” and he raced out the back door, slamming it hard behind him. Lamentations growled. Jimmy Lee flung himself at the dog and held his muzzle. Through the window, Geneva saw a streak in the forest. It became a woman running around to the back of the cabin. Looking out the back, she saw her disappear into the woods.

“Okay,” said Jimmy Lee. “She’s gone. If we high tail it now, we’ll make it back afore dark. Come on!” he urged, flinging open the front door and racing for the cover of the trees.