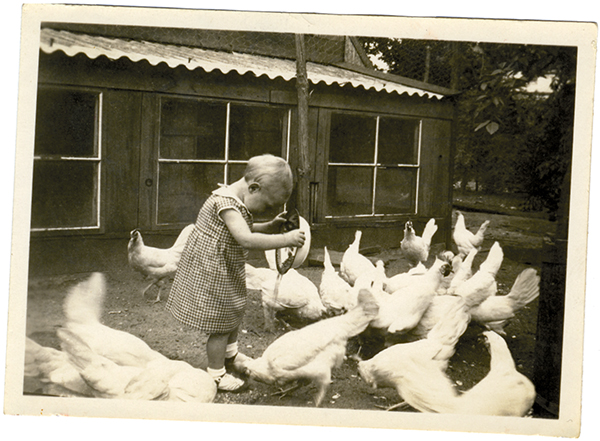

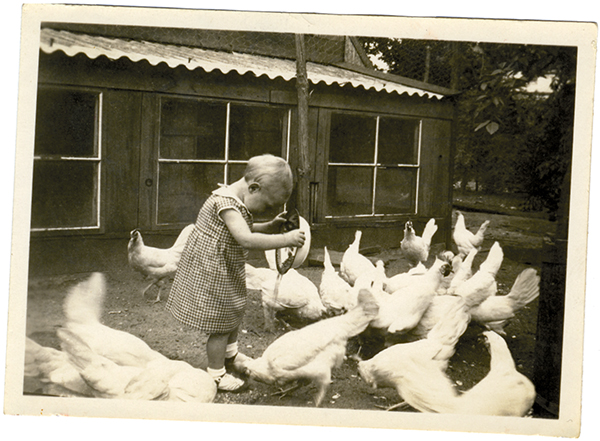

MY UNDERSTANDING of food gardening comes from deep time, from my great-great-grandfather who was an estate gardener in Fryslân, the Netherlands, where Friesian cows hail from. In later life he was registered as a kooltjer, a grower of four main vegetable crops: potatoes, cabbages, carrots, and onions. Maybe he became a market gardener because socioeconomic changes caused people to give up growing the family’s food in favor of working for wages. Food had to be purchased and someone else had to grow it. His son operated a vegetable shop as well as teaching school, and his grandson, my grandfather, owned a vegetable shop and wholesale business. One of my grandfather’s sons, my uncle, grew oranges in California. On my mother’s side, Uncle Wim took me for walks from the time I toddled through his pride-and-joy food garden in Laren, North Holland.

Yet, just as surely as I carry this joyous history of food growing and harvesting, I suspect that my ongoing concern with hunger and food shortages also comes from deep time and from both sides of the family, as well as my personal experience of famine.

During 1944 and 1945, I endured a famine and, at 5 feet 8 inches tall, was reduced to 75 pounds of bone and sinew. I carry the memories of my hometown, Hilversum (population 80,000 in the 1940s), breaking down as war action cut off the region. All trees became firewood, as did doors, cupboards, furniture, and fences. Cats, dogs, and rabbits disappeared. I starved rather than eat our rabbit Trudy. Mice, rats, and birds went into the pot. Rivers were fished out. We ate chard—normally reserved for pig fodder—and tulip bulbs, which made me ill. I dug for grass roots under the snow to steady my stomach. A long winter of famine ensued during which 24,000 people died of starvation. Now, I witness the world’s food-producing regions declining again through wars, landmines, and farmers’ deaths. All famines are caused by war. In peacetime, crop failures through natural calamities, usually local and short-term, can be met by rapid food aid.

I became a food gardener after I immigrated to Australia, in my first backyard. My daughter, son, and grandson now grow their own herbs, fruits, and vegetables. Yet I know people with no food-growing history whatsoever who produce impressive vegetables at first try! The time is here for everyone to get in touch with food at a grassroots level. Even if you do not have a garden, you can start or join a community garden in your neighborhood.

By growing some of your own food and starting a pantry collection of staples, you take control of your food needs if times of chaos should arrive. Meanwhile, you eat healthier, fresher, tastier food, enjoy gentle exercise, and make new friends. Nothing unites people more congenially than eating, swapping, and comparing locally grown good food. Food gardening is the most intelligent adult endeavor on earth and ought to be understood by anyone who eats.

Lolo Houbein